Nursing work stoppages are a significant concern within healthcare organizations, deeply affecting business operations, staff dynamics, and organizational stability. Using data triangulation, this qualitative study investigated the complex factors contributing to nursing work stoppages among unionized nurses in Southern California, aiming to uncover nuanced perceptions and identify effective resolution strategies. Using semi-structured interviews with 15 participants and a focus group session, this study analyzed in-depth qualitative data to comprehensively understand the motivations behind these collective actions. Thematic analysis revealed several key findings about factors that drive nursing work stoppages, included a lack of administrative support, inadequate staffing, and limited clinical decision-making autonomy. Emotional stress and frustration over poor leadership engagement and insufficient feedback mechanisms exacerbated nurses’ feelings of disempowerment and dissatisfaction. These key findings confirmed that psycho-social and job-related factors significantly influence the decision to participate in strikes. The study findings suggest several strategies for healthcare administrators to mitigate the impact of nursing work stoppages, such as improving communication and feedback channels, providing more robust administrative and emotional support, and addressing the chronic staffing shortages contributing to nurse burnout. Additionally, fostering greater autonomy and decision-making power for nurses can enhance job satisfaction and reduce the frequency of strikes.

Key Words: nursing work stoppages, healthcare administration, nurse autonomy, staffing, professional development, collective action in healthcare, job satisfaction in healthcare

Nursing work stoppages pose significant risks to patient care, organizational stability, and the well-being of healthcare workers (Essex et al., 2022; Kelly et al., 2021). This study centered on California, specifically Southern California, which has experienced some of the highest rates of nursing work stoppages in the United States. Nursing work stoppages pose significant risks to patient care, organizational stability, and the well-being of healthcare workers. Unionized nursing strikes, often driven by concerns such as inadequate pay, unfavorable working conditions, and chronic understaffing, have emerged as a prominent issue in the healthcare industry (Quesada-Puga et al., 2024). Historically, significant labor movements, such as the San Francisco nurse strike, have led to revisions of the Taft-Hartley Act, granting nurses and other not-for-profit hospital workers the right to collective bargaining and strikes (Bowling et al., 2022). These events reflect the systemic nature of labor disputes and their legislative impact on healthcare.

Recent studies have linked nursing work stoppages to deeper issues, including burnout, dissatisfaction, and compassion fatigue among nurses. Researchers like Aiken et al. (2018) have demonstrated the critical connection between adequate nurse staffing, patient outcomes, and nursing burnout, while workforce analyses have revealed alarming nurse turnover rates between 2020 and 2021 (Schwatka et al., 2024). This exodus from bedside care highlights the urgency of addressing workload issues to maintain workforce stability and healthcare quality. Recent studies have linked nursing work stoppages to deeper issues, including burnout, dissatisfaction, and compassion fatigue among nurses.

By applying Social Movement Theory (SMT) (Jasper, 2010) and the Job Characteristics Model (JCM) (Hussein, 2018), this qualitative study explored psycho-social and job-related factors contributing to nursing work stoppages and identified strategies to mitigate their occurrence. The conceptual framework integrates the emphasis of SMT on psycho-social elements—such as emotions, meaning, and collective agency- with JCM focus on job design components like autonomy, task significance, and feedback. This combination provided a holistic understanding of nurses' motivations to participate in nursing work stoppages.

These theoretical constructs are visually represented in Figure 1 below that illustrates the interconnectedness of psycho-social factors and job characteristics. The model emphasizes how dissatisfaction in job design components, such as limited autonomy, low task significance, and insufficient feedback, intensifies collective action when reinforced by social movement dynamics like emotional solidarity and shared grievances (Jasper, 2010; Hussein, 2018). This integrated perspective offered deeper insights into the root causes of nursing work stoppages and highlights effective pathways for intervention.

Figure 1. Conceptual Framework

Note: This visual, created by this researcher, illustrates the relationship between the job characteristics model (JCM) and social movement theory (SMT) in nursing work stoppages. Job characteristics, such as autonomy, task significance, and feedback, influence job satisfaction. When these are lacking, dissatisfaction grows. SMT explains how shared grievances and emotional bonds among nurses amplify this dissatisfaction, leading to strikes. This framework highlights how occupational and psychosocial factors combine to drive collective actions. This framework highlights how occupational and psychosocial factors combine to drive collective actions.

The research study discussed within highlighted key drivers of dissatisfaction, including understaffing, limited autonomy, and a lack of professional development opportunities, which often culminate in collective action. This study aimed to provide actionable insights for healthcare administrators by addressing these challenges, fostering a positive work environment, and reducing turnover.

Key Research Questions

The following questions guided this study:

- RQ1: What are the perspectives of Southern California nurses on participation in nursing work stoppages throughout Southern California?

- RQ2: What strategies can healthcare administrators implement to reduce the likelihood of future nursing work stoppages throughout Southern California?

Through a thorough analysis of these questions, this study underscored the need for systemic reforms that prioritize nurse well-being, enhance job satisfaction, and ensure stable workforce environments. By combining theoretical insights with practical implications, this research contributes to the broader understanding of labor relations and workforce challenges in the healthcare sector, paving the way for sustainable solutions.

Literature Review Summary

This literature review laid the groundwork for the study by examining nursing work stoppages in Southern California's healthcare system. In this section, I synthesize existing research to identify the causes, dynamics, and potential solutions to mitigate nursing strikes.

Theoretical Consideration

Social movement theory (Jasper, 2010) focuses on collective motivations for nursing work stoppages, highlighting the role of emotions, meaning, and interactions as psycho-social drivers. Jasper’s (2010) framework underscores how shared grievances and systemic issues, such as unsafe working conditions, lack of support, and insufficient recognition, lead to mobilization efforts. For instance, research by Gastón (2022) revealed that collective bargaining in unionized environments transformed grievances into actionable demands, often driven by moral visions to defend patient care and professional integrity. The COVID-19 pandemic amplified nurses’ frustrations, as increased workloads, inadequate personal protective equipment, and extended shifts heightened burnout (Murphy, 2022; Vindrola-Padros et al., 2020). Social media platforms further accelerated mobilization, providing virtual spaces for collective organizing and emotional expression (Mirbabaie et al., 2021). Social media platforms further accelerated mobilization, providing virtual spaces for collective organizing and emotional expression

Complementing this perspective, the job characteristics model (Hussein, 2018) examines how specific job attributes such as autonomy, task significance, and feedback, impact nurses' satisfaction and engagement. Hussein’s (2018) model shows deficiencies in these areas, such as poor staffing ratios, administrative barriers, or limited decision-making power, heighten dissatisfaction and increase the likelihood of nursing work stoppages. Belrhiti et al. (2020) demonstrated that autonomy and decision-making significantly influence nurses’ job satisfaction, while lack of feedback on performance creates disengagement. Similarly, Nie et al. (2023) found that job autonomy fosters proactive role adaptation, mitigating stress and improving resilience to organizational changes. Without these job design elements, nurses experience moral distress and emotional exhaustion, which exacerbate the desire for collective action (Gafni-Lachter et al., 2017).

Key Drivers of Work Stoppages

The literature discusses several key drivers of nursing work stoppages. Chronic understaffing remains a critical factor, increasing workloads, reducing patient care quality, and contributing to nurse burnout (Aiken et al., 2018; Dall’Ora et al., 2022). Gastón (2022) further linked understaffing to perceptions of inequity and feelings of undervaluation, increasing frustration that fuels nursing work stoppages. Poor workplace conditions such as long hours, inadequate safety measures, and insufficient resources, exacerbate job dissatisfaction and emotional strain (Pyhäjärvi & Söderberg, 2024). Administrative shortcomings, such as lack of leadership engagement, ineffective communication, and exclusion from critical decision-making processes, were highlighted as major triggers (Abd El-Fatah et al., 2018; Bennett et al., 2020). Chronic understaffing remains a critical factor, increasing workloads, reducing patient care quality, and contributing to nurse burnout

Additionally, economic grievances, including stagnant wages and inadequate benefits, remain central concerns, particularly in high-cost regions like California (Moore, 2017). Psychological and emotional strain also emerges as a recurring theme. Studies by Lamoureux et al. (2024) revealed that moral distress resulting from systemic issues such as coercive care practices, aggression exposure, and unsafe staffing, heightens emotional fatigue among nurses. This emotional toll not only impacts individual well-being but also triggers organizational instability as nurses seek collective solutions (Quesada-Puga et al., 2024)

Impact on Healthcare Organizations

Nursing work stoppages have profound implications for healthcare organizations and patient care. Empirical studies show that strikes disrupt patient services, delay treatments, increase mortality and readmission rates due to staffing reductions (Allen et al., 2019; Essex et al., 2022). Financially, organizations face considerable costs from temporary staffing, lost revenue, and administrative disruptions (Zdechlik, 2016; Patel et al., 2020). For example, the University of Vermont Medical Center strike resulted in $432,059 in lost profit within weeks (Patel et al., 2020). However, nursing work stoppages have also served as catalysts for systemic reforms, such as implementing safe staffing policies, improving working conditions, and enhancing professional recognition (Van den Heede et al., 2020). Gastón’s (2022) analysis highlighted how nurse unions’ advocacy led to transformative changes, balancing economic demands with ethical responsibilities to patient care. Additionally, economic grievances, including stagnant wages and inadequate benefits, remain central concerns...

To prevent nursing work stoppages, the literature emphasizes proactive strategies. Enhanced administrative support, including open communication, transparent leadership, and collaborative decision-making, promotes organizational trust and nurse engagement (Waird, 2023). Addressing chronic understaffing through robust workforce planning and improved nurse-to-patient ratios reduces workloads and burnout (Aiken et al., 2018). Providing opportunities for professional development and career advancement boosts nurses’ sense of value, motivation, and long-term commitment (Shenoy, 2021; Umar & Umar, 2024). Emotional and psychological support programs (e.g., wellness initiatives, counseling services, and burnout mitigation strategies) have been shown to alleviate workplace stress (Shiri et al., 2023). Finally, competitive compensation and benefits packages tailored to regional living costs address economic grievances and reduce turnover rates (Quesada-Puga et al., 2024). Nursing work stoppages have profound implications for healthcare organizations and patient care.

The interconnected dynamics of social movement motivations and job-related factors highlight the need for systemic reforms in healthcare environments. Integrating insights from the social movement theory and the job characteristics model thus created a comprehensive lens to understand and address nursing work stoppages. This synthesis underscores the importance of fostering equitable, supportive, and transparent workplace conditions to improve nurse satisfaction, reduce burnout, and ensure workforce stability. By leveraging these insights, the research delved into nurses’ perspectives to propose actionable strategies for healthcare administrators to foster a more sustainable and harmonious nursing environment.

Study Methodology

Design and Sample

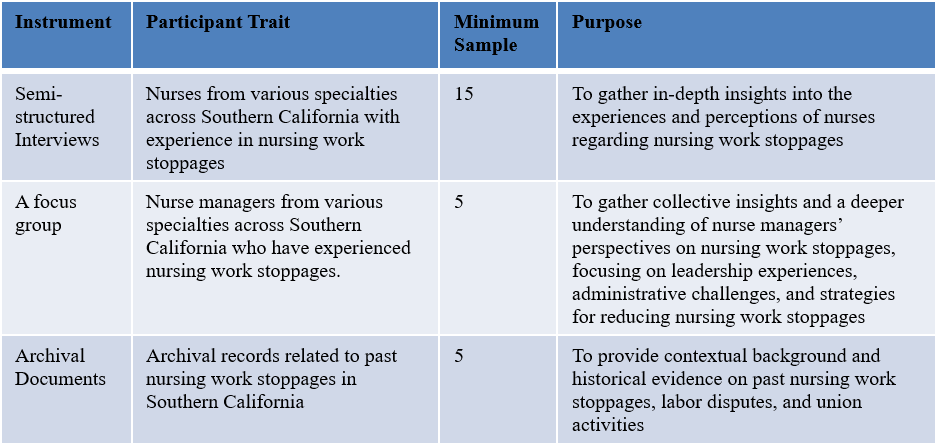

This study utilized a qualitative study approach, combining semi-structured interviews, a focus group, and archival records to comprehensively explore nursing work stoppages and labor relations in Southern California. This methodology was selected for its capacity to capture the nuanced perspectives and experiences of nurses directly involved in or impacted by nursing work stoppages. By focusing on the lived experiences and perceptions of participants, this study aimed to uncover key factors driving nursing work stoppages and identify practical strategies for their resolution.

Qualitative research can provide a profound understanding of complex social phenomena. This approach is particularly effective in healthcare research, where capturing the intricate interplay of emotions, interactions, and organizational dynamics is essential. As noted by Sanfey (2024) and Ahmed et al. (2024), qualitative methods are well-suited for delving into the complexities of nursing work stoppages, offering a rich and nuanced exploration of the subject matter. The flexibility and adaptability of qualitative research made it ideal for this study, allowing the researcher to examine various dimensions of nursing work stoppages and labor relations in real-world contexts.

The study design, guided by Percy et al. (2015), provided a robust framework to investigate the phenomenon within its bounded context. The linear-analytic structure of the study design allowed for a systematic exploration of the "how" and "why" questions central to this research. This methodological choice facilitated the triangulation of multiple data sources, enhancing the study's credibility by capturing diverse perspectives and providing rich insights. Figure 2 provides additional information about the population and sample for the study in the context of data collected, with further explanation in the section below.

Figure 2. Population & Sample

Note. The sample size for this study was based on achieving data saturation, achieved at 15 interviews. This study included 15 semi-structured interviews, a focus group with 5 nurse managers drawn from interviewees, and 5 archival documents to ensure comprehensive data collection and rich insights into the experiences and perspectives of nurses regarding nursing work stoppages.

Sample Selection and Recruitment. Participants were recruited from five healthcare facilities across Southern California, representing 10 departments and specialties to ensure a diverse and representative sample of nursing perspectives. The final sample included 15 unionized nurses and five nurse managers who had directly experienced or been impacted by a nursing work stoppage. Recruitment was conducted through a combination of professional networking platforms, including LinkedIn, and targeted email outreach using flyers and invitation letters. Participants were recruited from five healthcare facilities across Southern California, representing 10 departments and specialties...

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria. Participants were selected based on two specific inclusion criteria: (1) they were unionized nurses or nurse managers currently or formerly employed in healthcare facilities across Southern California, and (2) they had direct experience with or had been affected by a nursing work stoppage within the last 5 years. Nurse managers and unionized nurses were not intentionally recruited from the same institutions, allowing for a broader range of perspectives. Participants were not intentionally paired across nurse and nurse manager roles, preserving confidentiality and fostering open dialogue. Mixed purposeful sampling, supported by established qualitative trustworthiness guidance (Zia Ul Haq et al., 2023), was used to recruit nurses and nurse managers with direct experience of work stoppages in Southern California. This recruitment strategy supported methodological triangulation and contributed to a comprehensive understanding of nursing work stoppages' structural and emotional dimensions.

Ethical Considerations. Ethical assurances included informed consent, rigorous anonymization of participant data, and adherence to Institutional Review Board (IRB) guidelines. Confidentiality was maintained through stringent data security protocols, and participants were informed of their rights and the voluntary nature of their involvement. Reflexivity and member checking further supported the trustworthiness of the findings, ensuring that participants’ perspectives were accurately represented.

Data Collection

Semi-Structured Interviews. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 15 nurses from various specialties across Southern California. This method allowed for an in-depth exploration of individual experiences, providing detailed insights into participants' perspectives on nursing work stoppages. The open-ended nature of the questions enabled participants to freely share thoughts while ensuring that discussions remained focused on the research objectives. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 15 nurses from various specialties across Southern California.

Focus Group. A focus group was conducted with five nurse managers, all of whom had participated in the individual interviews. This format facilitated dynamic discussions and collective insights, allowing for a deeper understanding of leadership challenges, administrative hurdles, and strategies for mitigating nursing work stoppages. The focus group also corroborated and expanded upon the findings from the individual interviews.

Archival Records. As part of this study’s data triangulation strategy, five archival documents were reviewed to provide historical context to supplement and validate findings from the interviews and focus group. These publicly available documents were selected for their relevance to nursing work stoppages and healthcare labor dynamics in California and beyond. The archival records included articles by:

- Aiken et al. (2018), who examined hospital nurse staffing and patient outcomes;

- Berger (2022), who reported on large-scale nurse strikes and demands for safe staffing;

- Chima (2020), who explored the ethical and moral dimensions of healthcare labor actions;

- Abd El-Fatah et al. (2018), who detailed the roles of nurse managers during strike conditions; and

- Essex et al. (2023a), who conducted a global meta-analysis of the impact of healthcare strikes on patient mortality.

These records were treated as secondary data sources and analyzed qualitatively to provide contextual support and contrast for emergent themes. For instance, Aiken et al.’s (2018) findings on staffing ratios and burnout informed the analysis of participants’ emotional strain and motivations for collective action, while Essex et al. (2023a, 2023b) and Berger (2022) contextualized participants’ concerns about administrative disengagement and systemic neglect. Rather than serving only as literature citations, these archival materials directly informed the interpretation of study findings and supported the thematic development around emotional exhaustion, administrative support, and perceived injustice.

Data Management and Security

This study employed a web-based application for qualitative research, for coding and thematic analysis, ensuring efficiency and rigor in data handling. The transcription feature of an online collaboration platform facilitated accurate and secure data collection, while encrypted storage and password-protected access safeguarded participant confidentiality.

Data Analysis Framework

This study employed thematic analysis with constant comparison, as outlined by Percy et al. (2015). This 13-step process involved coding, clustering, and identifying emergent themes, ensuring a rigorous and systematic approach to data analysis. The iterative nature of the process allowed for continuous refinement of the findings, ensuring they were comprehensive and reflective of participants' perspectives. Data collection continued until thematic saturation was reached after 15 interviews, ensuring no new themes or information emerged, thereby confirming the adequacy of the sample size and enhancing the trustworthiness (Zia Ul Haq et al., 2023) of the findings.

Researcher Role and Ethical Considerations. This researcher played a pivotal role in designing and implementing the data collection instruments, ensuring ethical standards, and maintaining neutrality throughout this study. Ethical considerations included obtaining informed consent, safeguarding participant confidentiality, and adhering to strict data security measures. These practices ensured the integrity and credibility of the research while fostering a safe environment for participants to share their experiences. Neutrality and objectivity were critical to minimizing bias and ensuring the validity of the findings. This researcher approached this study with an open mind, avoided preconceived notions, and adhered to established ethical guidelines. By fostering a respectful and supportive atmosphere during interviews and focus group sessions, this researcher enabled participants to discuss sensitive topics without hesitation.

Thematic Analysis Process. The thematic analysis followed a systematic approach to ensure rigor and reliability (Percy et al., 2015). The analysis began with familiarization, which involved reviewing transcripts and archival records to understand the data comprehensively. This step was followed by initial coding, where key themes were identified and organized using Dedoose (Dedoose, n.d.). Software. These codes were then revisited and refined for relevance, ensuring alignment with the research questions and improving clarity. Themes were grouped according to research questions, defined with a clear scope, and structured to reflect relationships between primary themes and sub-themes.

The final stages of analysis involved thematic refinement to enhance coherence and completeness, followed by thematic saturation, confirming that no new themes had emerged during later stages of coding. Cross-validation through triangulation and member checking was employed to strengthen trustworthiness (Zia Ul Haq et al., 2023). This rigorous process culminated in a detailed analytical report, supported by data and verbatim quotes, ensuring transparency and depth of understanding.

Assumptions, Limitations, and Delimitations. Key assumptions included the expectation of shared experiences among participants, while limitations addressed potential biases, recruitment challenges, and recall issues. This study was delimited to Southern California nurses and their experiences within the last five years, ensuring a focused and relevant investigation. By including perspectives from both nurse managers and frontline staff, the study captured a holistic view of nursing work stoppages and labor relations.

Study Results and Discussion

Participant Demographics

Table 1 presents the demographic details of participants in this study, including identifiers for interview participants (I-1 to I-15) and those who participated in the focus group. The designators reflect each participant’s involvement, with some participants also identified by their focus group codes (e.g., I-5FG-1, I-6FG-2). The table includes information on age, gender, years of nursing experience, tenure at their current organization, and job titles.

Table 1. Summary of Participant Demographics

|

Participant |

Age |

Gender |

Years as Nurse |

Organization Tenure |

Job Title |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

I-1 |

35 |

female |

11 |

7 |

Registered Nurse |

|

I-2 |

29 |

female |

6 |

4 |

Registered Nurse |

|

I-3 |

27 |

female |

1 |

1 |

Registered Nurse |

|

I-4 |

39 |

male |

12 |

12 |

Registered Nurse |

|

I-5FG-1 |

50 |

male |

20 |

10 |

Nurse Manager |

|

I-6FG-2 |

38 |

female |

13 |

10 |

Nurse Manager |

|

I-7 FG-3 |

42 |

male |

20 |

15 |

Nurse Manager |

|

I-8 |

33 |

female |

7 |

4 |

Registered Nurse |

|

I-9 |

46 |

male |

12 |

8 |

Registered Nurse |

|

I-10 |

31 |

female |

11 |

7 |

Registered Nurse |

|

I-11FG-4 |

45 |

male |

14 |

8 |

Nurse Manager |

|

I-12FG-5 |

37 |

male |

6 |

1 |

Nurse Manager |

|

I-13 |

49 |

female |

10 |

8 |

Registered Nurse |

|

I-14 |

47 |

female |

23 |

18 |

Registered Nurse |

|

I-15 |

52 |

female |

12 |

10 |

Registered Nurse |

Emerging Themes

Data analysis identified nine key emerging themes that addressed this study’s research questions: emotions, meaning, task significance, autonomy, feedback, administrative support, staffing, and professional development. The findings provided a comprehensive understanding of the psycho-social and job-related factors driving nursing work stoppages. Table 3 provides an overview of the themes, detailed in the following sections.

Table 3. Overview of Study Themes

|

Theme |

Description |

Supporting Insights |

|---|---|---|

|

Emotions |

Captures the range of emotional responses from nurses, including stress, frustration, and solidarity, often influenced by work conditions. |

“During nursing work stoppages, I felt a mix of empowerment, solidarity, and frustration.” (I-13) |

|

Meaning |

Explores the sense of purpose and fulfillment nurses derive from patient care, and how these experiences impact their motivation and morale. |

“Helping patients recover and providing support during difficult times is incredibly fulfilling.” (I-8) |

|

Interactions |

Describes the quality and nature of interactions among nurses, patients, colleagues, and administration, impacting collaboration and support. |

“Positive interactions with coworkers and my manager help me feel supported and valued.” (I-7FG-3) |

|

Task significance |

Highlights the critical role nurses perceive they play in patient care, reflecting the importance of their contributions to health outcomes. |

“We are the backbone of patient care, yet we’re often overlooked.” (I-2) |

|

Feedback |

Encompasses the role of feedback both formal and informal in shaping nurses’ professional growth, job satisfaction, and feelings of value. |

“Constructive feedback greatly enhances my job satisfaction by highlighting areas for improvement.” (I-11FG-4) |

|

Autonomy |

Reflects nurses’ desire for decision-making power in patient care and the impact of administrative constraints on their sense of control. |

“I have the freedom to make decisions about patient care, such as prioritizing tasks based on patient needs.” (I-10) |

|

Administrative support |

Focuses on the need for supportive management and open communication, emphasizing the importance of effective leadership and resource access. |

“There needs to be a more open and transparent dialogue between staff and management.” (I-5FG-1) |

|

Staffing |

Emphasizes the impact of nurse-to-patient ratios on care quality and nurses’ well-being, highlighting the critical need for adequate staffing. |

“Improving staffing ratios would significantly enhance our well-being as healthcare workers.” (I-4) |

|

Professional development |

Highlights the importance of growth opportunities, career advancement, and continuing education as key factors in nurse engagement and retention. |

“Access to continuing education and clear career pathways would make us feel valued and invested in.” (I-10) |

Theme 1: Emotions. The theme of emotions highlighted the intense feelings that nurses experienced during nursing work stoppages, including frustration, stress, and solidarity. Frustration frequently stemmed from poor communication and lack of support. One nurse noted, “The constant policy changes without proper communication make our job harder” (I-8). Stress was closely tied to chronic understaffing and inadequate resources, with another participant emphasizing, “When you’re stretched so thin, it breaks your heart because you can’t give patients the attention they deserve” (I-3). These findings align with Berger (2022), who reported on nurses' emotional strain during large-scale strikes, often exacerbated by administrative disconnection and resource scarcity. The theme of emotions highlighted the intense feelings that nurses experienced during nursing work stoppages...

Despite these challenges, solidarity among nurses provided strength and resilience, as one participant shared, “We’re in this together. When things get tough, we lean on each other” (I-5FG-1). However, this unity often carried emotional conflict, as another nurse explained, “You want to support your team, but you also feel responsible for the patients” (I-7FG-3). This mirrors the concept of collective resilience noted by Aiken et al. (2018), who found that solidarity among nurses during periods of staffing shortages fosters mutual support and collective coping mechanisms, reducing feelings of isolation and emotional fatigue.

Theme 2: Meaning. The theme of meaning highlighted how nurses found purpose through patient care and relationships. One participant noted, “Building relationships with patients and witnessing their progress is deeply meaningful” (I-1). Another shared, “Knowing my care and advocacy make a positive impact keeps me committed” (I-2). However, administrative burdens often undermined this fulfillment. A nurse explained, “The most meaningful aspects are patient care, but administrative tasks and lack of support detract from it” (I-3).

Simplifying processes and prioritizing patient-centered care were emphasized as solutions. “Reducing bureaucratic hurdles and giving nurses more control would make work more meaningful,” said one participant (I-5FG-1). Nurses also stressed the importance of being included in decision-making, with one nurse stating, “Being involved enables us to better influence patient recovery and feel valued” (I-1).

Aiken et al. (2018) confirmed that meaningful work tied to patient outcomes improves engagement and retention, as nurses who perceive their work as impactful are more likely to remain committed during challenging times. This aligns with Chima (2020), who emphasized the ethical significance of meaningful patient care, noting that nurse satisfaction and advocacy are strengthened when nurses feel their work directly impacts patient outcomes. Moreover, Chima (2020) argued that when nurses are actively involved in patient-centered decision-making, it enhances their sense of purpose and reduces the emotional toll of work stoppages. Organizations can enhance job satisfaction and prevent nursing work stoppages by reducing barriers and valuing nurses' voices through inclusive decision-making and administrative support. ...as nurses who perceive their work as impactful are more likely to remain committed during challenging times.

Theme 3: Interactions. Interactions are central to nurses’ job satisfaction and well-being. Positive connections with patients and families provided meaning and motivation: “I value building relationships with patients and their loved ones the most, as these interactions make me feel valued, needed, and appreciated” (I-15). Another noted, “Supportive and empathetic interactions with patients and their families reinforce the importance of my role and provide a deep sense of purpose” (I-4).

Support from colleagues also boosted morale. One nurse emphasized, “Assigning mentors on each unit to connect with float staff would improve communication and ensure they feel integrated and confident” (I-15). Another stated, “My emotional well-being would improve with more opportunities for debriefing and emotional support after difficult interactions” (I-13). These sentiments reflect Aiken et al. (2018), who found that supportive team interactions significantly mitigate burnout and enhance job satisfaction among nurses. In challenging work environments, peer support acts as a buffer against emotional strain, fostering collective resilience.

In contrast, interactions with the administration were often frustrating. A participant explained, “Interactions with administration can be strained due to differing priorities and a lack of urgency or empathy” (I-6FG-2). Another added, “The focus on policies over patient care, with financial interests prioritized, makes these interactions unpleasant” (I-9). This sentiment was echoed: “Negative encounters add to stress when nurses’ opinions are disregarded” (I-4). Berger (2022) supports these findings, indicating that administrative disconnects and prioritization of financial goals over patient care contribute significantly to nurse dissatisfaction during strikes and work stoppages.

Despite these challenges, positive interactions with patients and teams served as a critical buffer. “Positive interactions with my team and patients play a crucial role in boosting my morale” (I-9), while another noted, “Productive, positive interactions enrich my work purpose” (I-11FG-4). This highlights the protective nature of team cohesion and patient relationships, acting as stabilizing forces amid organizational stress. ...positive interactions with patients and teams served as a critical buffer.

Theme 4: Task Significance. Task significance underscored the nurses’ essential role in patient care and the broader healthcare system. “Nurses are instrumental in saving lives, often in ways that aren’t immediately visible,” one participant noted, emphasizing their responsibilities in monitoring, early detection, emotional support, and advocacy (I-8). Another stated, “Our contributions are vital to patient outcomes and recovery, but when we feel undervalued, the risk of a nursing strike increases” (I-4).

Participants highlighted the deep connection between their sense of purpose and their ability to deliver high-quality care. “Achieving good patient outcomes depends on nurses; most of all, our presence is indispensable to patient satisfaction and hospital success” (I-2). However, nurses felt compelled to advocate for better conditions when their work is unsupported or unrecognized. “A nurse work stoppage becomes likely when our vital contributions are disregarded,” one nurse emphasized (I-9). Participants highlighted the deep connection between their sense of purpose and their ability to deliver high-quality care.

These findings align with Aiken et al. (2018), who noted that when nurses perceive their contributions as undervalued, it negatively impacts morale and increases turnover risks. The study emphasizes that recognizing the critical role nurses play in patient monitoring and recovery reduces burnout and improves retention. Similarly, Berger (2022) reported that the perception of task insignificance during strikes often stems from inadequate recognition of nurses' roles within the healthcare system. This lack of acknowledgment contributes to the escalation of work stoppages as nurses strive to highlight their impact on patient safety and recovery. Furthermore, Essex et al. (2023a, 2023b) found that during healthcare strikes globally, the devaluation of nurses' contributions not only led to disruptions in care but also heightened patient mortality rates. This underscores the moral and ethical implications of task significance, linking nurse recognition to not just staff morale, but life-saving outcomes. Recognizing and valuing nurses’ contributions is critical to fostering a positive work environment, enhancing patient care, and preventing disruptions. When nurses feel that their efforts are acknowledged and respected, engagement increases, and the likelihood of work stoppages diminishes.

Theme 5: Feedback. Feedback played a pivotal role in nurses’ growth and satisfaction. “Constructive feedback enhances my job satisfaction by acknowledging strengths and areas for improvement,” one participant noted (I-13). Timely feedback was particularly valued, with another emphasizing, “Prompt feedback corrects mistakes early and reinforces positive behavior” (I-3). Informal recognition, like a simple “Good job,” also boosts morale and confidence (I-13).

However, participants stressed the need for balance: “Constant criticism without celebrating successes can be demoralizing” (I-6FG-2). Nurses indicated that both formal and informal feedback drives professional development, validates efforts, and fosters a positive work environment. This aligns with Aiken et al. (2018), who found that supportive and consistent feedback correlates with higher job satisfaction and lower turnover rates. ...during healthcare strikes, the absence of constructive feedback contributes to heightened emotional distress and disengagement among nurses.

Essex et al. (2023b) further emphasized that during healthcare strikes, the absence of constructive feedback contributes to heightened emotional distress and disengagement among nurses. Their global analysis showed that open communication and real-time performance feedback mitigated feelings of isolation and discontent during labor disputes. This perspective is supported by Abd El-Fatah et al. (2018), who highlighted that transparent communication and feedback from nurse managers during strike conditions can significantly reduce confusion and maintain staff morale. In environments where nurses receive timely and meaningful feedback, there is a noticeable reduction in burnout and a stronger commitment to organizational goals (Berger, 2022). Recognizing both individual and team contributions fosters a sense of belonging and professional growth, reducing the risk of labor disputes. Structured feedback mechanisms that are supportive rather than punitive enhance engagement and retention, especially during organizational stress and work stoppages.

Theme 6: Autonomy. Autonomy in patient care was critical for nurses’ professional satisfaction, empowering them to deliver effective and responsive care. One nurse stated, “I have the freedom to make decisions about patient care, such as prioritizing tasks based on patient needs” (I-1), while another added, “Using my expertise to deliver effective and responsive care makes a huge difference” (I-4). Autonomy fosters professional confidence, as one participant noted, “The freedom to make my own decisions has greatly improved my happiness at work and boosted my confidence” (I-10). ...administrative restrictions on autonomy frustrated many participants.

However, administrative restrictions on autonomy frustrated many participants. “Sometimes, it feels like the rules prevent us from doing what’s best for the patient,” shared one nurse (I-13). Another explained, “Nursing is about making decisions based on the patient’s immediate needs, but when every step has to be approved, it slows down care and adds stress” (I-6FG-2). Nurses emphasized that autonomy is essential for effective care, with one stating, “Autonomy isn’t just a perk, it’s necessary for good patient care” (I-9).

These findings are supported by Abd El-Fatah et al. (2018), who emphasized that greater autonomy for nurses during strike conditions improves patient care outcomes and reduces burnout. Their study showed that when nurses are empowered to make real-time decisions, patient care is less disrupted, even in crisis scenarios. Essex et al. (2023a, 2023b) highlighted that globally, nurse autonomy correlates with better patient outcomes and reduced mortality rates during healthcare disruptions, underscoring the life-saving implications of independent clinical decision-making. Furthermore, Berger (2022) identified the lack of autonomy as a primary driver for nurse-initiated work stoppages, highlighting how administrative constraints not only hinder patient care but also fuel collective action among nursing staff. The evidence suggests that fostering nurse autonomy is not merely a matter of professional preference but a crucial component of patient safety, job satisfaction, and labor stability. “During the strike, it felt like we were battling a faceless administration,”

Theme 7: Administrative Support. Administrative support was vital for nurse satisfaction and morale, with participants emphasizing the need for open communication and visible leadership. One nurse stated, “There needs to be a more open and transparent dialogue between staff and management” (I-5FG-1), while another shared, “We rarely saw anyone from management come to hear our concerns or show empathy” (I-6FG-2). The lack of engagement from administrators led to frustration and disconnection. “During the strike, it felt like we were battling a faceless administration,” noted one participant (I-5FG-1).

Nurses called for practical support, such as timely feedback and policies that address burnout. “Having a manager listen and take feedback seriously would foster trust,” said one nurse (I-12FG-5). This reflects findings by Abd El-Fatah et al. (2018), who emphasized that visible, responsive leadership during nursing work stoppages is instrumental in reducing misunderstandings and improving morale. Their study demonstrated that when nurse managers were actively involved and transparent in communication, strike durations were shorter, and staff resilience increased.

Essex et al. (2023a, 2023b) further highlighted the global impact of administrative support during healthcare strikes, noting that visible leadership not only reduces mortality rates but also stabilizes team cohesion during crisis periods. Their meta-analysis revealed that when leadership is accessible and communicative, nurses are less likely to disengage during organizational disruptions. Conversely, Berger (2022) identified that the absence of proactive administrative engagement often exacerbates disconnection and dissatisfaction, contributing to longer and more intense work stoppages.

When financial and policy-focused decisions are prioritized over patient care and staff well-being, trust erodes, and morale declines. To prevent such breakdowns, evidence suggests that strong administrative support, paired with transparent communication, is essential for creating a cohesive and supportive work environment. Visible leadership, accessible management, and empathetic engagement not only improve morale but also enhance patient outcomes during both routine operations and strike conditions. When financial and policy-focused decisions are prioritized over patient care and staff well-being, trust erodes, and morale declines.

Theme 8: Staffing. Adequate staffing emerged as a critical concern, directly affecting patient care and nurse well-being. “When short-staffed, it compromises the care we provide to patients,” shared one nurse (I-7FG-3). Another added, “Adequate staffing is vital for patient recovery and our job satisfaction” (I-6FG-2). Chronic understaffing fueled burnout and turnover. “It’s a revolving door; nurses leave because they can’t handle the constant pressure,” noted one participant (I-10). Nurses criticized administrative priorities, with one stating, “The focus is on cutting costs, not ensuring safe care” (I-12FG-5). Managers echoed these concerns, calling the situation “unsustainable” (I-6FG-2). As one nurse emphasized, “Proper staffing isn’t just about us, it’s about keeping patients safe” (I-15).

These findings align with Aiken et al. (2018), who found that inadequate nurse staffing compromises patient safety and increases nurse turnover rates. Their research demonstrated that patient outcomes, including mortality rates, are directly tied to nurse-to-patient ratios. The study emphasizes that when staffing levels are insufficient, care quality and nurse morale suffer, leading to a vicious cycle of burnout and attrition. Berger (2022) reported that nurse strikes are often fueled by demands for safe staffing levels, emphasizing that workforce shortages are not just logistical challenges but moral and ethical concerns. Berger’s findings align with participant experiences in this study, suggesting that understaffing is not only a workforce issue but a catalyst for labor disputes, as nurses advocate for safe and ethical care conditions.

Further emphasizing this point, Essex et al. (2023a, 2023b) provided a global perspective, revealing that healthcare strikes rooted in staffing concerns lead to higher patient mortality rates and worsened health outcomes. Their global meta-analysis stressed that countries with higher nurse-to-patient ratios experience fewer healthcare disruptions during strikes, underscoring the life-saving importance of adequate staffing. Evidence suggests that investing in adequate staffing is essential to ensure care quality, retain nurses, and maintain a functional healthcare system. Addressing understaffing is not merely a matter of resource allocation; it is a critical factor in patient safety, nurse retention, and the prevention of work stoppages. ...healthcare strikes rooted in staffing concerns lead to higher patient mortality rates and worsened health outcomes.

Theme 9: Professional Development. Professional development was a key driver of nurse satisfaction and retention. Participants highlighted the value of mentorship and growth opportunities, with one nurse noting, “Having the chance to grow professionally keeps me engaged and motivated” (I-8). Another emphasized, “Advanced certifications and specializations, funded by the hospital, show the administration values our expertise” (I-11FG-4). Mentorship was described as “crucial,” with one nurse stating, “Having a senior nurse guide me through complex cases has been invaluable” (I-12FG-5).

However, barriers such as time and funding were common concerns. A participant shared, “The biggest barrier to professional development is time. Paid time for learning would show genuine support” (I-6FG-2). Another remarked, “Budget cuts limit course access, making us feel undervalued” (I-7FG-3). These experiences reflect findings from Chima (2020), who emphasized that financial pressures often undermine ethical commitments to staff development, leading to constraints that reduce engagement and increase turnover. The study highlighted that nurses are more likely to remain in their positions when institutions prioritize professional growth and provide tangible support for continuing education. ...nurses are more likely to remain in their positions when institutions prioritize professional growth and provide tangible support...

Similarly, Aiken et al. (2018) highlighted that institutions that prioritize professional development see improved patient outcomes and retain experienced nursing staff for more extended periods. Their research indicated that ongoing training and mentorship programs help mitigate the impact of staffing shortages by improving nurse preparedness and resilience during high-stress periods, including strikes. Furthermore, Essex et al. (2023a, 2023b) underscored the global significance of professional development during work stoppages. Their meta-analysis revealed that facilities maintaining strong training and mentorship programs during strikes saw faster recovery and better patient continuity.

Essex et al. (2023b) argued that investing in professional growth during a crisis stabilizes care and reduces staff turnover rates, enhancing overall healthcare stability. Evidence suggests that investing in professional development enhances engagement, reduces turnover, and improves patient care outcomes. Strategic support for mentorship, continuing education, and skill development is essential for nurse satisfaction and organizational resilience during labor disruptions.

Summary of Themes

Interview and focus group data analysis uncovered key themes that underscore the factors driving nursing work stoppages. These themes provided a comprehensive understanding of the challenges nurses face. Administrative Support emerged as the most frequently discussed theme, highlighting the critical role of effective leadership and transparent communication in addressing nursing work stoppages. One participant noted, “The constant policy changes without proper communication make our job much harder” (I-8). Nurses expressed significant dissatisfaction with administrative visibility and engagement during critical moments, emphasizing that poor communication contributes directly to the escalation of work stoppages.

Closely following were themes related to emotional strain and autonomy. Many nurses described frustration and stress resulting from limited autonomy in patient care and insufficient feedback mechanisms. One participant emphasized, “Without proper support, it jeopardizes our licenses and puts patient lives at risk” (I-15). Chronic understaffing further compounded emotional strain, as nurses struggled to manage excessive patient loads with minimal support. Another nurse reflected, “When you are stretched so thin, it breaks your heart because you cannot give patients the attention they deserve” (I-3).

Despite these challenges, nurses highlighted meaningful aspects of their work, such as patient interactions and task significance, which provided a sense of purpose and motivation. However, poor interactions with leadership and a lack of professional growth opportunities intensified dissatisfaction. Nurses described feeling undervalued due to limited career pathways and professional development access, leaving many feeling stagnant and unappreciated.

Negative interactions with leadership further exacerbated this dissatisfaction, reflecting the complex interplay of job-related and emotional factors that influence decisions to participate in work stoppages. Participants noted that greater administrative transparency and consistent engagement could alleviate some of these tensions and improve workplace morale. These findings suggest that addressing these core issues, particularly administrative support, emotional well-being, and professional development, may reduce the occurrence of nursing work stoppages and enhance overall job satisfaction. ...addressing these core issues, particularly administrative support, emotional well-being, and professional development, may reduce the occurrence of nursing work stoppages...

Theoretical Framework Integration

The study findings can be integrated within the frameworks of the job characteristics model (Hussein, 2018) and social movement theory (Jasper, 2010). Autonomy, task significance, and feedback, key components of the job characteristics model, emerged as critical to understanding nurses’ job satisfaction and retention. Concurrently, shared emotional experiences and systemic grievances aligned with social movement theory, illustrating how structural and emotional factors drive collective action in the nursing workforce.

Emotional Dynamics and Collective Action. Emotions such as frustration, stress, and solidarity were central to nurses' decisions to strike. As SMT posits, shared grievances serve as catalysts for collective action. Nurses expressed disillusionment with chronic understaffing, administrative inefficiencies, and inadequate leadership support. One participant shared, "The emotional toll of the job, combined with the lack of support from management, made it impossible not to stand up for ourselves" (I-11FG-4). Solidarity emerged as a powerful motivator, fostering a collective identity that unified nurses in advocating for systemic change. Addressing these emotional drivers through improved communication, visible leadership, and emotional support systems is vital for reducing the likelihood of future nursing work stoppages (Murphy, 2022; Gaston, 2022). Solidarity emerged as a powerful motivator, fostering a collective identity that unified nurses in advocating for systemic change.

Structural Barriers to Job Satisfaction. Chronic understaffing, limited autonomy, and insufficient feedback eroded nurses' job satisfaction, as reflected in JCM. Nurses frequently cited the inability to provide adequate care due to excessive workloads as a source of emotional and professional disengagement. Empowering nurses through increased autonomy in clinical decision-making and involving them in policy development fosters engagement and strengthens their sense of control, which are key drivers of satisfaction according to JCM (Hussein, 2018). Maintaining adequate staffing ratios and introducing flexible workforce strategies, such as float pools, are crucial for alleviating workload stress and improving patient outcomes (Aiken et al., 2018).

Other Considerations

This study illuminated the multifaceted factors influencing nurses' decisions to participate in nursing work stoppages across Southern California, emphasizing the critical role of emotional, structural, and professional dynamics. Drawing on social movement theory (Jasper, 2010) and the job characteristics model (Hussein, 2018), the findings highlight how shared grievances, job satisfaction, and organizational support intersect to drive collective action. The integration of established frameworks advances academic discourse and underscores the value of interdisciplinary approaches to understanding healthcare labor issues. This section considers recommendations and strategies to address systemic and emotional challenges in nursing. This study illuminated the multifaceted factors influencing nurses' decisions to participate in nursing work stoppages across Southern California...

Study Strengths. The multi-source data collection process's robustness reinforces this study's methodological rigor. Semi-structured interviews provided detailed personal insights, while the focus group captured shared managerial experiences and strategies. Archival records enriched these findings by offering historical and organizational context, validating and contrasting primary data. These records shed light on nurse managers' roles during strikes (Abd El-Fatah et al., 2018) and examined staffing, work environments, and their effects on patient and hospital outcomes (Aiken et al., 2018). The findings contribute to the broader literature on nursing labor dynamics by exploring how emotional and structural factors intersect in nursing work stoppages

Professional Development and Retention. Opportunities for professional growth and structured feedback mechanisms were identified as essential to enhance nurse engagement. The absence of clear career pathways and continuing education opportunities often led to feelings of stagnation and disengagement. Structured performance reviews, mentorship programs, and leadership training were strongly associated with improved job enrichment and retention (Hussein, 2018). By prioritizing investments in these areas, healthcare organizations can cultivate a motivated and resilient workforce, addressing systemic issues contributing to nursing work stoppages. Participants emphasized the importance of transparent communication and visible leadership.

The Role of Administrative Support. Administrative support, or the lack thereof, emerged as a critical factor influencing nurses’ dissatisfaction. Participants emphasized the importance of transparent communication and visible leadership. Transparent communication fosters trust and reduces dissatisfaction (Murphy, 2022; Gaston, 2022). Leadership training incorporating empathy, conflict resolution, and emotional intelligence can further address frustrations and build a supportive environment (Waird, 2023; Quesada-Puga et al., 2024). Creating a supportive environment through positive and productive interactions can enhance nurses' sense of purpose and engagement. Table 2 considers the study themes in the context of administrative support, with examples of supporting quotes from participants.

Table 2. Administrative Support Context Across Themes

|

Theme |

Key Motivators / Content |

Supporting Quotations |

|---|---|---|

|

1. Emotions |

• Frustration and stress caused by understaffing and weak communication |

“During nursing work stoppages, I felt a mix of empowerment, solidarity, and frustration.” (I-13) |

|

2. Meaning |

• Purpose derived from patient care and advocacy |

“Helping patients recover and providing support during difficult times is incredibly fulfilling.” (I-8) |

|

3. Interactions |

• Supportive relationships with peers and leaders boost morale |

“Positive interactions with coworkers and my manager help me feel supported and valued.” (I-7FG-3) |

|

4. Task Significance |

• Nurses value their critical role in patient care |

“We are the backbone of patient care, yet we are often overlooked.” (I-2) |

|

5. Feedback |

• Constructive, timely feedback enhances motivation and growth |

“Constructive feedback greatly enhances my job satisfaction.” (I-11FG-4) |

|

6. Autonomy |

• Freedom to make clinical decisions increases satisfaction |

“We need more freedom to make decisions on the spot without getting approval for every little thing.” (I-6FG-2) |

|

7. Administrative Support |

• Transparent communication and visible leadership reduce dissatisfaction |

“There needs to be a more open and transparent dialogue between staff and management.” (I-5FG-1) |

|

8. Staffing |

• Chronic understaffing drives burnout and reduces care quality |

“Improving staffing ratios would significantly enhance our well-being as healthcare workers.” (I-4) |

|

9. Professional Development |

• Growth and learning opportunities sustain engagement |

“Access to continuing education and clear career pathways would make us feel valued and invested in.” (I-10) |

(Gaston, 2022; Hussein, 2018; Murphy, 2022; Quesada-Puga et al., 2024; Waird, 2023)

Implications for Practice

Several actionable recommendations are proposed to address the challenges identified in this study, as follows:

- Strengthening administrative support through transparent communication, consistent feedback, and visible leadership is critical for rebuilding trust and addressing grievances early (Bennett et al., 2020).

- Improving staffing ratios, such as implementing safe nurse-to-patient ratios and offering flexible scheduling, can alleviate workload stress, reduce burnout, and enhance the quality of patient care (Aiken et al., 2018).

- Empowering nurses by increasing their autonomy in decision-making fosters engagement and reduces frustration, as emphasized in the job characteristics model (Hussein, 2018).

- Providing structured mentorship programs, clear career pathways, and continuing education opportunities is vital for retention and motivation, helping to mitigate feelings of stagnation.

- Offering regular and meaningful feedback mechanisms to ensure that nurses feel valued and supported, further enhancing job satisfaction (Hussein, 2018).

- Supporting nurses’ mental health through access to counseling services, stress management programs, and peer support can help address emotional strain and foster resilience.

- Recognizing the task significance of nurses by actively acknowledging their contributions reinforces their sense of purpose and commitment, which is essential for long-term engagement and satisfaction.

These strategies collectively offer a pathway to address systemic challenges while promoting a supportive and motivated nursing workforce.

Implications for Theory and Future Research

This research advances social movement theory (Jasper, 2010) and the job characteristics model (Hussein, 2018) by demonstrating their applicability in understanding collective labor actions within healthcare. These frameworks provided valuable insights into how emotional and structural factors drive nursing work stoppages. To build on these findings, future research should expand the geographic scope and sample size to explore regional and cultural variations, offering a more comprehensive understanding of these dynamics across diverse settings. Employing mixed-methods approaches can further quantify the long-term impacts of strikes on patient care and nurse retention, providing both qualitative depth and statistical rigor. Investigating leadership styles and union-management collaboration can identify effective strategies to mitigate labor disputes.

Investigating leadership styles and union-management collaboration can identify effective strategies to mitigate labor disputes. Future studies should also examine the role of professional identity theory in understanding nurses’ resilience amid high-stress environments, shedding light on how professional values and identity influence nurses' ability to navigate workplace challenges and maintain their commitment to patient care. These avenues for research offer significant potential to deepen theoretical understanding and inform practical solutions in healthcare labor relations.

Conclusion

This study underscores the urgent need for healthcare organizations to address the root causes of nursing work stoppages through a comprehensive and multifaceted approach. By integrating emotional, structural, and professional considerations, healthcare administrators can create a supportive and engaged work environment that enhances nurse retention, job satisfaction, and patient outcomes. This research, focused on Southern California, explored the psychosocial and job-related factors driving nurses’ decisions to participate in nursing work stoppages, including emotional strain, lack of autonomy, inadequate administrative support, and chronic understaffing. Utilizing social movement theory (Jasper, 2010) and the job characteristics model (Hussein, 2018), this study identified critical elements fueling dissatisfaction and collective mobilization among nurses in unionized healthcare settings.

The importance of this qualitative study lies in its ability to bridge theoretical concepts with actionable strategies, offering healthcare administrators and policymakers a roadmap for mitigating nursing work stoppages. The findings emphasize the profound emotional and job-related stressors nurses face, such as the need for transparent communication, safe staffing ratios, consistent leadership engagement, and opportunities for professional growth and autonomy. These factors impact nurses’ job satisfaction and directly influence their decisions to engage in collective action. This research aligns with and reinforces existing literature on burnout, emotional labor, and job satisfaction, while applying these insights to the unique context of Southern California’s healthcare system. It highlights the role of union dynamics and labor relations in shaping nurses’ workplace experiences, further validating and expanding the applicability of social movement theory and the job characteristics model. The study findings call for healthcare organizations to prioritize effective communication, mental health support systems, professional development opportunities, and union-management collaboration to create a resilient and sustainable nursing workforce.

In conclusion, this research underscores the importance for healthcare organizations to address the emotional, structural, and professional challenges nurses face, as doing so is essential to reduce the risk of nursing work stoppages and promoting organizational stability. By investing in leadership development, enhancing workplace conditions, and supporting nurses’ well-being, healthcare institutions can build a harmonious and productive workforce, leading to better employees and patient outcomes. These findings offer a blueprint for systemic change, emphasizing that prioritizing nurses’ needs is not only an ethical imperative but also a strategic necessity for the long-term success of healthcare delivery.

Acknowledgments: Thanks to the study participants for their time and insights, which made this research possible. The researcher created all tables and images referenced in this manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement: The Trident University Institutional Review Board approved this study on August 15, 2024. This study complies with the ethical principles outlined in The Belmont Report and the Common Rule.

Author

Tiffany R. Grant, DBA

Email: Tiffany.RGrant@my.trident.edu

Dr. Grant holds a Doctorate in Business Administration and a PhD in Educational Leadership from Trident University International. With over 15 years of experience in healthcare management and leadership, she specializes in workforce engagement and operational efficiency. Her research focuses on mitigating labor disputes in healthcare through strategic organizational reforms.

References

Abd El-Fatah, I. M., Sleem, W. F., & Ata, A. A. (2018). Role of the nurse managers during nursing personnel strikes. IOSR Journal of Nursing and Health Science, 7(1), 77–86. https://www.iosrjournals.org/iosr-jnhs/papers/vol7-issue1/Version-6/J0701067786.pdf

Ahmed, F., Ali, K., Mann, M., & Sibbald, S. L. (2024). Thematic analysis of using visual methods to understand healthcare teams. The Qualitative Report, 29(6), 1525–1541. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2024.6618

Aiken, L. H., Cerón, C., Simonetti, M., Lake, E. T., Galiano, A., Garbarini, A., Soto, P., Bravo, D., & Smith, H. L. (2018). Hospital nurse staffing and patient outcomes. Revista Médica Clínica Las Condes, 29(3), 322–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmclc.2018.04.011

Allen, J. I., Aldrich, L. B., & Adams, M. A. (2019). Preparing for large-scale disruptions in health care delivery: Nursing strikes and beyond. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 17, 1424–1427. https://www.cghjournal.org/article/S1542-3565(19)30138-7/pdf

Belrhiti, Z., Van Damme, W., Belalia, A., & Marchal, B. (2020). Unravelling the role of leadership in motivation of health workers in a Moroccan public hospital: A realist evaluation. BMJ Open, 10(1), Article e031160. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031160

Bennett, P., Noble, S., Johnston, S., Jones, D., & Hunter, R. (2020). COVID-19 confessions: A qualitative exploration of healthcare workers experiences of working with COVID-19. BMJ Open, 10(12), Article e043949. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043949

Berger, R. (2022). More than 8,000 RNs and health care workers demand safe staffing. National Nurse Magazine. https://www.nationalnursesunited.org/article/sutter-rns-and-health-care-workers-hold-one-day-strike

Bowling, D., III, Richman, B. D., & Schulman, K. A. (2022). The rise and potential of physician unions. JAMA, 328(7), 617–617. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.12835

Chima, S. C. (2020). Doctor and healthcare workers strike: Are they ethical or morally justifiable: Another view. Current Opinion in Anesthesiology, 33(2), 203–210. https://doi.org/10.1097/aco.0000000000000831

Dall’Ora, C., Saville, C., Rubbo, B., Turner, L., Jones, J., & Griffiths, P. (2022). Nurse staffing levels and patient outcomes: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. International Journal of Nursing Strikes, 134, Article 104311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2022.104311

Dedoose. (n.d.). Home | Dedoose. Retrieved June 9, 2023, from https://www.dedoose.com/

Essex, R., Ahmed, S., Elliott, H., Lakika, D., Mackenzie, L., & Weldon, S. M. (2023a). The impact of strike action on healthcare delivery: A scoping review. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 38(3), 599–627. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.3610

Essex, R., Burns, C., Evans, T. R., Hudson, G., Parsons, A., & Weldon, S. M. (2023b). A last resort? A scoping review of patient and healthcare worker attitudes toward strike action. Nursing Inquiry, 30, Article e12535. https://doi.org/10.1111/nin.12535

Essex, R., Weldon, S. M., Thompson, T., Kalocsányiová, E., McCrone, P., & Deb, S. (2022). The impact of health care strikes on patient mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Health Services Research, 57(6), 1218–1234. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.14022

Gafni-Lachter, L., Admi, H., Eilon, Y., & Lachter, J. (2017). Improving work conditions through strike: Examination of nurses’ attitudes through perceptions of two physician strikes in Israel. Work, 57(2), 205–210. https://doi.org/10.3233/wor-172560

Gastón, A. (2022). Moralizing the strike: How nurses’ collective action shaped healthcare. American Journal of Sociology, 128(2), 54–82. https://doi.org/10.1086/720300

Hussein, A. (2018). Test of Hackman and Oldham’s job characteristics model at general media sector. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 8(1), 345–365. https://doi.org/10.6007/ijarbss/v8-i1/3813

Jasper, J. M. (2010). Social movement theory today: Toward a theory of action? Sociology Compass, 4(11), 965–976. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9020.2010.00329.x

Kakar, Zia Ul Haq, M., Rasheed, R., Rashid, A., & Akhter, S. (2023). Criteria for assessing and ensuring the trustworthiness in qualitative research. International Journal of Business Reflections, 4, 150–173. https://doi.org/10.56249/ijbr.03.01.44

Kelly, L. A., Gee, P. M., & Butler, R. J. (2021). Impact of nurse burnout on organizational and position turnover. Nursing Outlook, 69(1), 96–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2020.06.008

Lamoureux, S., Mitchell, A. E., & Forster, E. M. (2024). Moral distress among acute mental health nurses: A systematic review. Nursing Ethics, 31(7), 1178–1195. https://doi.org/10.1177/09697330241238337

Mirbabaie, M., Brünker, F., Wischnewski, M., & Meinert, J. (2021). The development of connective action during social movements on social media. ACM Transactions on Social Computing, 4(1), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.1145/3446981

Moore, A. (2017). Nursing shortages: how bad will it get? Nursing Standard, 31(37), 26–28. https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.31.37.26.s24

Murphy, M. J. (2022). Exploring the ethics of a nurses’ strike during a pandemic. American Journal of Nursing, 122(3), 49–54. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.naj.0000823000.39601.b1

Nie, T., Tian, M., Cai, M., & Yan, Q. (2023). Job autonomy and work meaning: Drivers of employee job-crafting behaviors in the VUCA times. Behavioral Sciences, 13(6), Article 493. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13060493

Patel, N. P., Hudson, M. E., Mayhew, C. R., Breidenstein, M. W., Marmanides, A. P., & Tsai, M. H. (2020). Ramifications of a nursing strike on operating room efficiency. Perioperative Care and Operating Room Management, 21, Article 100101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcorm.2020.100101

Percy, W., Kostere, K., & Kostere, S. (2015). Generic qualitative research in psychology. The Qualitative Report, 20(2), 76–85. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2015.2097

Pyhäjärvi, D., & Söderberg, C. B. (2024). The straw that broke the nurse’s back—Using psychological contract breach to understand why nurses leave. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 80(12), 4989–5002.

Quesada-Puga, C., Izquierdo-Espin, F. J., Membrive-Jiménez, M. J., Aguayo-Estremera, R., Cañadas-De La Fuente, G. A., Romero-Béjar, J. L., & Gómez-Urquiza, J. L. (2024). Job satisfaction and burnout syndrome among intensive-care unit nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 82, Article 103660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2024.103660

Sanfey, D. (2024). ‘Enough is enough’: A mixed methods study on the key factors driving UK NHS nurses’ decision to strike. BMC Nursing, 23, Article 247. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-01793-4

Schwatka, N. V., Keniston, A., Astik, G., Linker, A., Sakumoto, M., Bowling, G., Auerbach, A., & Burden, M. (2024). Hospitalist shared leadership for safety, health, and well-being at work: United States, 2022–2023. American Journal of Public Health, 114(S2), 162–166. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2024.307573

Shenoy, A. (2021). Patient safety from the perspective of quality management frameworks: A review. Patient Safety in Surgery, 15, Article 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13037-021-00286-6

Shiri, R., Nikunlaakso, R., & Laitinen, J. (2023). Effectiveness of workplace interventions to improve health and well-being of health and social service workers: A narrative review of randomised controlled trials. Healthcare, 11(12), Article 1792. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11121792

Umar, T. R., & Umar, B. F. (2024). Modelling the link between conflict management styles, organisational trust and employee job satisfaction. EPRA International Journal of Research & Development, 9(1), 148–164. https://doi.org/10.36713/epra15559

Van den Heede, K., Cornelis, J., Bouckaert, N., Bruyneel, L., Van De Voorde, C., & Sermeus, W. (2020). Safe nurse staffing policies for hospitals in England, Ireland, California, Victoria and Queensland: A discussion paper. Health Policy, 124(10), 1064–1073. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2020.08.003

Vindrola-Padros, C., Chisnall, G., Cooper, S., Dowrick, A., Djellouli, N., Symmons, S. M., Martin, S., Singleton, G., Vanderslott, S., Vera, N., & Johnson, G. A. (2020). Carrying out rapid qualitative research during a pandemic: Emerging lessons from COVID-19. Qualitative Health Research, 30(14), 2192–2204. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732320951526

Waird, A. (2023). Preventing care factor zero: Improving patient outcomes and nursing satisfaction and retention through facilitation of compassionate person-centred care. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 40(4), 33–42.

Zdechlik, M. (2016, November 15). Nurses strikes cost Allina more than $100 million. https://www.mprnews.org/story/2016/11/15/nurses-strike-cost-allina-more-than-100-million

Zia Ul Haq, K., Rasheed, R., Rashid, A., & Akhter, S. (2023). Criteria for assessing and ensuring the trustworthiness in qualitative research. International Journal of Business Reflections, 4(2), 150–162. https://doi.org/10.56249/ijbr.03.01.44