The nursing shortage continues to grow, leaving healthcare systems and patients in a precarious situation. A major reason for the shortage is the lack of nursing faculty to educate future nurses, which has hindered nursing programs nationwide from accepting students interested in a nursing career. This qualitative study explored the existing academic nurse educator shortage and sought solutions that an important stakeholder group, the public and business sector/business owners, might implement to mitigate the dual shortage of professional nurses and academic nurse educators. Using a modified Nominal Group Technique (NGT) design, the research team identified five major stakeholder groups which could benefit from addressing the academic nurse educator shortage. Team subgroups reviewed relevant literature and crafted recommendations to address the academic nurse educator shortage. This article discusses findings from one of these major stakeholders: the public and business/business owner sectors. Forty-five academic nurse educators were recruited from volunteers engaged in a national nursing education online forum and 25 participants completed the study. Five themes emerged: encourage lobbying efforts with legislators; engage the media in exposing the relationship of the academic nurse educator shortage and the nursing shortage; incentivize higher education opportunities for nurses to become academic nurse educators; elevate the life experience of patients; and stakeholder collaboration. A continued partnership between the public/business sectors/business owners and leaders within the profession of nursing must exist to enhance the academic nurse educator role. Only with this partnership can those within the profession of nursing continue to serve the public sustainably for years to come.

Key Words: Nursing shortage, academic nurse educators, nursing shortage, nursing workforce, public sector, business sector, quality nursing care, nominal group technique, patient stories, human experience, stakeholders, partnerships, qualitative research

The United States (U.S.) is functioning with a shortage of registered nurses. According to Aiken et. all. (2023), the nursing shortage existed well before the COVID-19 pandemic. The increase in healthcare demands, aging populations, retiring nurses, and changes in economic situations for healthcare organizations are all negative influences for the nursing shortage. As of 2020, the decrease in nurses was further impacted by the pandemic due to inadequate workplace support, a lack of new nurses to replace retirees, and nurses leaving the profession due to burnout (Udod, 2023). The nursing shortage continues to grow, leaving healthcare systems and patients in a precarious situation.

The nursing shortage continues to grow, leaving healthcare systems and patients in a precarious situation.

One major reason for the nursing shortage is the lack of nursing faculty to educate future nurses (American Association of Colleges of Nursing [AACN], 2022). For the purposes of this discussion, nursing faculty are defined as academic nurse educators (ANEs). ANEs are licensed registered nurses with an advanced degree who are employed by a university or college to teach nursing curricula. ANEs educate nursing students in classrooms, clinical laboratories, clinical patient settings, and simulated learning laboratories, whether in person or virtually (National League for Nursing [NLN], 2022). According to the AACN (2022) report on 2021-2022 Enrollment in Baccalaureate and Graduate Programs in Nursing, U.S. nursing schools turned away 91,938 qualified applicants from baccalaureate and graduate nursing programs due to insufficient number of faculty, clinical sites, classroom space, clinical preceptors, and budget constraints. Most responding schools identified the faculty shortage as a top reason for not accepting all qualified applicants.

One major reason for the nursing shortage is the lack of nursing faculty to educate future nurses.

A Special Survey on Vacant Faculty Positions released by AACN (2022) identified 2,166 full time faculty vacancies in a sample of 909 nursing schools with baccalaureate and/or graduate programs across the country. The inadequate number of ANEs is a grave national consideration as demand for nursing care cannot be met in part due to a lack of nurse faculty to educate new nurses (Jarosinski et al., 2022). Since the inability to educate and develop new nurses is a key contributing factor for the nursing shortage, an increase in ANEs must be addressed.

The AACN has taken several steps to address the ANE shortage (AACN, 2022). These include collecting and disseminating data to quantify the scope of the ANE shortage; forging a partnership with the Jonas Philanthropies (2020) to continue to support doctoral nursing students; advocating for new federal legislation and increased funding for graduate education; promoting faculty careers through the Graduate Nursing Student Academy (AACN, 2024); and collaborating with national nursing organizations and practice partners to continue to identify solutions. Even though AACN has taken these steps to address the ANE shortage, it is crucial to engage the public and business sectors, as they are the consumers of nursing care and key stakeholders in the attempts to address this critical issue.

Most responding schools identified the faculty shortage as a top reason for not accepting all qualified applicants.

A consortium of ANEs nationwide has created a working group to acknowledge, address, and actively move to change public awareness of the ANE crisis, which has resulted in the form of this collaborative research project. The purpose of this article is to describe the results of the systematic inquiry to identify and codify actionable information so the public and business sectors will be able to participate in strategies to increase the number of ANEs across the United States, thereby expanding the number of nurses to provide care. The stakeholders who are impacted the most by this research are the consumers of healthcare. Consumers of healthcare are the end receivers of the care delivered by nurses. The quality and manner in which healthcare is delivered to them will have long lasting consequences for years to come. The aim of this qualitative inquiry was to consider solutions that the public and business sectors/business owners might implement to mitigate the academic nurse educator shortage.

...it is crucial to engage the public and business sectors, as they are the consumers of nursing care and key stakeholders...

Background and Significance

The nursing shortage is influenced by social factors and government policies (Fox & Abrahamson, 2009). Those investigating the reasons for the nursing shortage cannot simply use hospital admission statistics as a measure of nursing demands. The number of nurses needed to adequately care for a population is a far more complex problem. Aiken (2007) has stated that the most significant factor in any labor shortage is not the lack of qualified applicants; it is the lack of available ANEs and resources to teach said applicants.

The increased diversity of career options for applicants and a more rigorous admission structure in nursing programs because of a lack of ANEs and college resources has contributed to the shortage of registered nurses. Federal policies such as the Nursing Education Loan Repayment Program (GovLoans, n.d.) add a third party to what would be a negotiation between nurses and employers in a free market. The question of reimbursement for healthcare services needs to be examined. In the United States, there is little difference in facility reimbursement for care, whether providing care of moderate quality or excellent care (Fox & Abrahamson, 2009).

The public and business sectors/owners need to know that the current nursing shortages could have long-lasting consequences...

The public and business sectors/owners need to know that the current nursing shortages could have long-lasting consequences (Buerhaus, 2021). There are two types of nursing shortages: background shortages and national nursing shortages. Background shortages develop when factors temporarily alter the demand. National nursing shortages are more severe, longer lasting, involve many healthcare facilities, and affect access to care, quality safety, and costs (Buerhaus, 2021). We are currently experiencing a national nursing shortage and need to change our present direction. We need to narrow the gap between society’s growing healthcare needs and the size, preparation, and distribution of the nursing workforce, all of which are inadequate (Kerfoot & Buerhaus, 2022)

Review of Literature

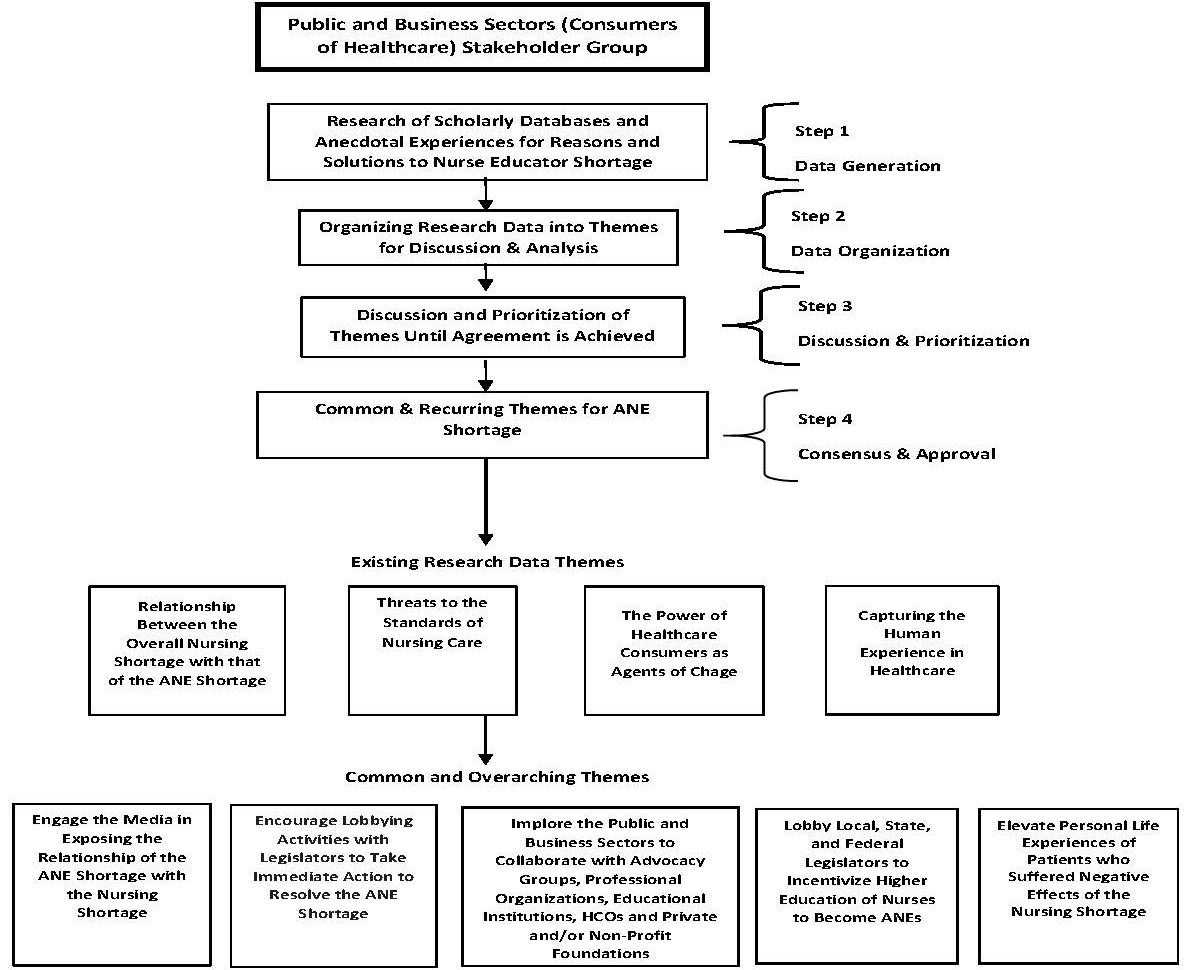

An analysis of existing literature revealed the following themes: the relationship between the dual shortages of number of nurses overall and the number of ANEs; threats to the standards of nursing care; the power of healthcare consumers as agents of change; and the human experience in healthcare. Each of these is briefly discussed below.

Relationship between the Dual Shortages

The relationship between the dual shortages of the number of nurses overall and the number of ANEs is an important contributor to the problem at hand. The current nursing shortage existed pre-COVID (Auerbach et al., 2012) and has escalated since COVID. Factors influencing the nursing shortage include an increased demand (e.g., the increasing aging population and the COVID pandemic), as well as mass exodus of nurses during the pandemic due to overwork, burnout, and fear of safety for themselves and their family during COVID (Buerhaus et al., 2023). The resulting shortage is aptly classified as dire (Bakewell-Sachs et al., 2022) and a crisis (Jarosinski et al., 2022). A significant contributing factor to the overall nursing shortage is the lack of ANEs (Aiken, 2007). According to the AACN (2022), 2,166 ANE vacancies were identified across the nation, thus forcing universities, colleges, and nursing schools to turn away over 91,000 viable nursing student applicants. This roadblock in the pipeline of preparing new nurses results in a lack of nursing care available and affects the standard of nursing care that can be provided.

The relationship between the dual shortages of the number of nurses overall and the number of ANEs is an important contributor to the problem at hand.

Threats to the Standards of Nursing Care

The public and business sectors/business owners need awareness about the basic standards of nursing practice set forth by the ANA (2021) so that their expectations for care will be in line with reality. This means that stakeholders must understand that while the professional nurse directs nursing care, an aide or other unlicensed assistive personnel may provide certain aspects of care (e.g., bathing, toileting). Nurses must assess patients by obtaining and interpreting vital signs (e.g., temperature, pulse, respiration, blood pressure) and ascertaining levels of pain or discomfort. While an aide or tech may measure these vital signs, only the nurse can interpret and act on the results.

Nurses administer medications and must assess any expected and untoward reactions that may result. Nurses must help patients understand the healthcare system. Thus, nurses explain transitions in care (e.g., progress in recovery from a joint replacement and moving to a rehabilitation unit, discharge teaching). Nurses provide instructions about how to take new medications at home, including anticipatory guidance. For example, if a patient is newly placed on anticoagulant medication to prevent blood clots, the nurse will provide guidance as to when to call the physician to report certain side effects. Regardless of the specific nursing action required by a healthcare situation, the public and business sectors/business owners deserve accurate and respectful care from those in the nursing profession.

Nursing shortages contribute to patient dissatisfaction and illness complications (Berhe et al., 2016). Additionally, the United States is increasingly becoming more diverse; the ability of the public and business sectors’/business owners to navigate the healthcare system and receive culturally competent, inclusive, and equitable care has become more challenging (Griese et al., 2020). Furthermore, care cannot occur if it cannot be accessed (Combs et al., 2021). For example, if there are not enough nurses to adequately staff a unit, beds may be closed. Nursing shortages contribute to patient dissatisfaction and illness complicationsIt may be several hours before patients in the emergency room awaiting admission to a facility can be transported to an inpatient room. The decrease in the number of nurses nationwide contributes to the decrease in the public and business sector/business owner access to safe, competent care.

The Power of Healthcare Consumers as Agents of Change

The public and business sectors/business owners are the consumers of the nation’s healthcare. The taxes that the public and business sectors/business owners pay locally, statewide, and/or federally are distributed, in part, for healthcare. Auerbach and colleagues (2012) explained how the government has aided in the formation of healthcare industries and services for decades. The intersection of these stakeholders, the tax system, government regulation, and healthcare access/financing provides an opportunity for them to work collaboratively to address the current nurse educator shortage.

The intersection of these stakeholders...provides an opportunity for them to work collaboratively to address the current nurse educator shortage.

The various connections of these stakeholders and systems offers an opportunity for both the public and business sectors/business owners to have a genuine voice in the effort to increase the national ANE workforce, and thus to address one compelling cause of the current nursing shortage. In addition, anyone who experiences healthcare, whether in the emergency department, the clinic, or the operating room, has a very human experience (The Beryl Institute, 2024). While the currency for business/business owners is the intersection of taxes, government regulation, and healthcare access and financing, the currency for patients is the stories that patients and families share after their healthcare experiences.

Capturing the Human Experience in Healthcare

Patient satisfaction has always been identified as one outcome of care. In recent years, the concept of patient satisfaction has been broadened and reconceptualized as patient experience or patient engagement (Wolf et al., 2014). The Beryl Institute (2024), a leader in the patient experience movement, now writes of the “human experience” in healthcare. For the Beryl Institute (2023), the human experience encompasses patient experiences, staff experiences, and the pervasive culture of a healthcare agency or entity. Thus, the human experience is not a line item (Wolf, 2022) and cannot be measured simply by a budget expenditure. The human experience is multifaceted and complex. It involves feedback, through patient surveys sent after discharge, or through complaints or compliments regarding care. It can also be captured through case studies or storytelling. The human experience in healthcare is altered by chaos in the workforce (Beryl Institute, 2023); this is especially so when there is a critical shortage of nurses.

Methods

Design

The research question that guided this qualitative inquiry was: What solutions could the public and business sectors/business owners implement to address the academic nurse educator shortage?

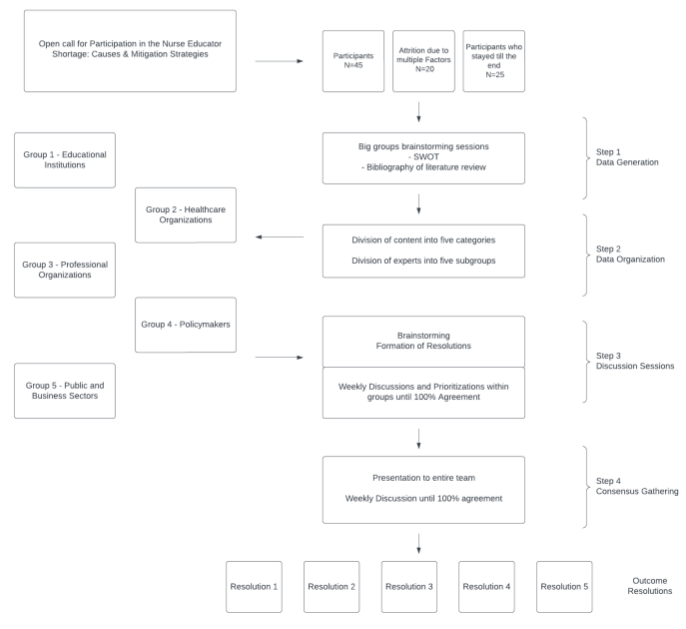

This qualitative research utilized the Nominal Group Technique (NGT) in an effort to obtain consensus from a wide spectrum of various sources; a process commonly employed in health and consumer group research (Allen et al., 2013; Manera et al., 2019; Mullen et al., 2021; Olsen, 2019). The NGT method provided the best mechanism to uncover strategies to address the worsening shortage of nurse educators. It involved four phases: 1) data generation, 2) data organization, 3) discussion and priorities, and 4) consensus (see Figure 1). We utilized a modified NGT because meetings were held via a virtual meeting platform, allowing participants across the country to readily brainstorm, discuss, analyze and agree on available data related to this research.

Figure 1. Schematic Representation of the Nominal Group Technique Used

Vardaman et al. (2024, April 17)

Sample

A convenience sample of 45 ANEs was recruited through an online discussion forum sponsored by a nursing education professional organization. We distributed a call for those interested in potentially serving on a task force to address the ANE shortage. Inclusion criteria included nurse educators with current or past clinical experiences and those with either prior or present healthcare or academic administrative roles. A final sample of 25 nurse educators participated in the full NGT process.

Protection of Human Participants

The IRB of Adelphi University reviewed the research protocol and deemed the study as exempt. The nurse educators were apprised of their rights as human subjects upon participating in the NGT project meetings. Consent to participate was established and implied when participants attended the required meetings and completed all the NGT steps. While participants engaged in the collaborative, iterative process of developing themes from the literature, and eventually articulating action steps for change, their identity was known to all other participants. However, the results reflect the consensus of the entire group, and ideas of no single participant were identifiable. Thus, a measure of anonymity was preserved.

Data-Gathering Procedures and Analysis

Published literature offers many variations to the steps used in NGT design (Allen et al., 2013; Atkins et al., 2023; Manera et al., 2019; Mullen et al., 2021; Olsen, 2019). We used a series of 12 virtual synchronous meetings that were conducted twice each week over six weeks. During these two hour meetings, the study team met to generate, discuss, and agree on ideas. At the initial meeting in May 2023, participants generated ideas through the use of a strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) analysis process. SWOT analysis is a tool used to understand internal and external factors that impact organizations (Teoli et al., 2022). Participants listed anecdotal evidence related to being an academic nurse educator on a SWOT analysis document over the course of the meeting and were encouraged to add to it over the following week.

During these two hour meetings, the study team met to generate, discuss, and agree on ideas.

For this research study, we used four steps to gather and analyze data: data generation; data organization; discussion and prioritization; and consensus. These four steps of the NGT were completed during the total number of meetings held. Note that given the iterative processes of this NGT, data gathering and analysis occurred throughout the project period. Most data gathering occurred in the first two steps, and most data analysis occurred in the latter two steps.

Data generation required each participant to search the literature, use personal and professional experiential anecdotes, and contribute various scenarios to illustrate recruitment and retention of ANEs and establish the severity of the ANE shortage. Data organization involved two activities. First, participants listing their contributions accordingly and appropriately into the four quadrants of the (SWOT) analysis diagram, and secondly they compiled an annotated bibliography of all the relevant research.

We identified five major stakeholders early in the discussion phase

Upon completion of the first two steps, the group transitioned to step three: discussion and prioritization. We identified five major stakeholders early in the discussion phase: educational institutions; healthcare organizations; policymakers; professional organizations; and the public and business/business owners sector. The larger group then divided into five subgroups to address each stakeholder. During the discussion and prioritization step, it was decided that each subgroup would develop a resolution addressed to each stakeholder group. The resolution would include recommendations to address the pressing and complex nurse educator shortage both comprehensively and collaboratively.

Elements of the SWOT analysis backed by relevant sources became the resolution statements for actionable items for the stakeholder group.

At the next meeting, participants of each subgroup, including this public and business sector (i.e., the consumers of healthcare), were asked to review the literature to generate supporting evidence for the results of the SWOT analysis. Elements of the SWOT analysis backed by relevant sources became the resolution statements for actionable items for the stakeholder group. Each stakeholder group closely examined the resolution statements and the substantiating evidence and literature, thoroughly discussed the relevance of the statements and the strength of the evidence, and established consensus through a robust give-and-take of each recommendation.

Each resolution statement was thus supported by scholarly literature, white papers, and organizational position statements. Additional discussions and prioritization occurred, as needed, at the subgroup level until each resolution was complete with practical, reasonable, and appropriate recommendations.

The resolutions served as action plans for stakeholder groups to implement. After 4 two-hour meetings of the subgroups, out of the total of 12 meetings by the entire group, the full group came The resolutions served as action plans for stakeholder groups to implement. together again to review the final list of recommendations by the subgroups. Each recommendation required full consensus (100%) from the entire group to move forward with the final resolution statements. Statements that did not initially achieve 100% consensus were again discussed in detail, with individual members asking questions and the subgroups providing support for the statement. Statements were reworded to increase precision, or deleted when it was determined that a statement did not meet the level or rigor required by the group to achieve full consensus.

Results

Demographics

Demographic and professional characteristics are detailed in the Table.

Table 1. Demographic and Professional Characteristics of the Sample (n=25)

|

Variable |

Number (Percentage) |

|---|---|

|

Gender Female Male |

23 (92) 2 (8) N=25 |

|

Race White African-American Asian |

16 (67) 3 (12) 5 (21) N=24 |

|

Ethnicity Hispanic Non-Hispanic |

0 (0) 25 (100) N=25 |

|

Age <30 30-40 41-50 51-60 >60 |

0 (0) 1 (4) 6 (25) 7 (29) 10 (42) N=24 |

|

Location by Region (Using U.S. census 4-region designation) Northeast South Midwest West

|

13 (54) 7 (29) 3 (13) 1 (4) N=24 |

|

Years in Nursing |

Range: 15 - 45 Mean: 33.9 N=24 |

|

Years as ANE |

Range: 4 – 36 Mean: 15.6 N=24 |

|

Administrative responsibility as ANE Yes No |

10 (42) 14 (58) N=24 |

|

Highest Degree Earned Masters Doctorate PhD DNP EdD |

5 (21)

12 (50) 5 (21) 2 (8) N=24 |

|

Licenses Held RN APRN Other |

23 (100) 5 (22) 1 (4) N=23 |

|

Certifications Held* CNE Clinical Specialty/Population-focused Administrative/Systems-level |

8 (28) 10 (34) 11 (38) N=21 persons responded; 29 responses overall |

*free-form responses

As the Table indicates, the 25 NGT participants were predominantly female, white, and aged over 50 years, with the majority residing in the northeast region of the United States. This was an experienced group of nurses, with the mean years in the nursing profession just under 40 and the mean years as an ANE just over 15. Over 40% of the ANEs held some form of administrative responsibility. Nearly 80% had earned doctoral degrees and over 22% percent were licensed as Advanced Practice Registered Nurses (APRNs). Twenty-one of the participants held one or more certifications, with nearly 30% holding the credential for Certified Nurse Educator (CNE).

Emerging Themes

The subgroup analyzed solutions proposed in the literature, as well as imagined creative and compelling actions which extended beyond the literature. Five major themes for the solutions emerged, including the need to 1) engage the media in exposing the relationship of the ANE shortage with the nursing shortage, 2) encourage lobbying activities with legislators to take immediate action to resolve the ANE shortage, 3) elevate personal life experiences of patients who suffered negative effects of the nursing shortage, 4) lobby local, state and federal legislators to incentivize higher education opportunities for nurses to become ANEs, and 5) implore the public and business sectors to collaborate with advocacy groups, professional organizations, educational institutions, healthcare organizations, and private and non-profit foundations.

Ultimately, the goal was for the public and business sectors to become advocates for nursing...

Ultimately, the goal was for the public and business sectors to become advocates for nursing, just as nurses have advocated for patients, families, and communities. Figure 2 illustrates the process used to generate the common themes used by stakeholders in healthcare. The following section discusses these themes individually.

Figure 2. Process of Generating Common Themes Used by the Public & Business (Consumers of Healthcare) Stakeholder Group

Note: ANEs – Academic Nurse Educators

HCOs – Healthcare Organizations

Discussion

Theme #1: Engage the Media

The first theme was to engage the media in exposing the relationship of the ANE shortage with the nursing shortage. This theme first requires that the public and business sectors/business owners be educated about the ANE shortage and its relationship to the broader overall shortage of professional nurses. It is important that the public and business sectors/business owners understand the systems level risks they may encounter due to nursing shortages, such as missed care, more complications, readmissions for the same healthcare problem, and other poor patient outcomes, including patient dissatisfaction (Berhe et al, 2016; Berkowitz, 2016; Kalisch, 2016). Public service announcements can inform the general public, as well as targeted short informational pieces to reach business leaders. Collaboration with respected organizations is also crucial in such a communication campaign.

It is important that the public and business sectors/business owners understand the systems level risks they may encounter due to nursing shortages...

Once this initial information is in front of the public and business sectors/business owners, it is more likely that a call to attend public forums could be received positively. Such public forums might emphasize the need to support legislation to fund nursing education. Funding has the potential to create more ANE positions, thereby increasing the capacity to educate new nurses to decrease the overall nursing shortage (Buerhaus et al., 2023).

Careful preliminary work by the subgroup was essential to the selection of key public leaders/business persons who might participate in such forums, as well as in crafting appropriate publicity for the wider public. As Wallach (1994) articulated in his seminal work on media advocacy, “media advocacy is defined as the strategic use of mass media to advance public policy initiatives” (p. 420). Wallach (1994) further positioned media advocacy as important to address the power gap rather than the knowledge gap. Such public forums might emphasize the need to support legislation to fund nursing education.

Theme #2: Encourage Lobbying Activities with Legislators

The second theme that emerged from our discussions was encouraging lobbying activities with legislators to take immediate action to resolve the ANE shortage. There is a critical need to fund the creation of a national center focused on nursing education and the development of nurse faculty and clinical preceptors to support both retention of current faculty and recruitment into the ANE role (National Advisory Council on Nurse Education and Practice [NACNEP], 2022). In addition, the American Hospital Association ([AHA], 2023) has urged Congress and the U.S. government to invest in nurse faculty salaries, as well as increase funding for current initiatives (i.e., the Health Resources and Services Administration [HRSA] Nurse Faculty Loan Program, Advanced Nursing Education Workforce program, National Health Service Corps, and the National Nurse Corps). While national nursing entities and allies have achieved some successes in lobbying legislators to take action regarding the ANE shortage, including the recent U.S. Department of Labor model incubator ([DOL], 2023), it is crucial that legislators hear the voices of the public and business sector.

Ideally, the template will provide a place for the sender to share a relevant, personal story about themselves, their family, or their employees...

One strategy to assist the public and business sector to engage in lobbying is to provide templates. Such templates are used to develop a clear, compelling, and consistent message. The public and business sectors/business owners, armed with a template letter/email, can petition healthcare insurance companies and private and public foundations to provide media coverage in support of the need for both ANEs and nurses (Bakewell et al., 2022). Ideally, the template will provide a place for the sender to share a relevant, personal story about themselves, their family, or their employees, which demonstrates the impact of a lack of ANEs as a major contributing factor to the broader nursing shortage.

Theme #3: Incentivize Nurses to Become ANEs

The third theme was even more specific to lobbying activities, i.e., lobby local, state, and federal legislators to incentivize higher education opportunities for nurses to become ANEs. Additional templates for letters/emails can provide key messages so that the public and business sectors/business owners can inform local, state, and federal government representatives about the Another solution created for the stakeholders is to enlist support of nursing associations, foundations, and health related businesses...critical shortage of ANEs (Bakewell-Sachs, 2022). Another solution created for the stakeholders is to enlist support of nursing associations, foundations, and health related businesses to create public service announcements that emphasize the need to increase the number of ANEs that will result in more new nursing graduates to improve patient-nurse ratios (Johnson & Johnson, 2023; McElroy, 2023). Beyond improving patient-nurse ratios, efforts to address the dual nursing shortages allow more opportunity to reach the desired goal of culturally competent healthcare for all (Klein, 2023; Nair & Adetayo, 2019; Ni Luasa et al., 2023).

Theme #4: Elevate Personal Life Experiences of Patients

Theme four addressed the idea of elevating personal life experiences of patients who have suffered the negative effects of the nursing shortage. Another important aspect of the call to action is the Another important aspect of the call to action is the strategic use of storytelling.strategic use of storytelling. The power of a first-person account, whether it was the story that went well or was lacking, can be very compelling, especially as it relates to the standard of care and the need for sufficient nursing resources. Working with public and business sectors/business owners to share stories of the patient (or human) experience brings into play powerful levers for change (Beryl Institute, 2024).

While definitions of patient experience vary (Wolf et al., 2014), treating the patient as a unique human being, inclusive of physical and psychosocial needs, is one vital aspect (Wasim et al., 2023). Careful consideration must be given to how and when to engage patients as partners in storytelling, as this places them in a vulnerable position (Metersky et al., 2023). Ultimately, elevating the human side of nursing care helps to tell the story of the dual nursing shortages and positions the public and business sectors/business owners and nurses as partners seeking further solutions.

Careful consideration must be given to how and when to engage patients as partners in storytelling, as this places them in a vulnerable position.

Theme #5: Collaboration with Systems Stakeholders to Increase Nurse Faculty Numbers

Finally, an “all hands-on deck” approach is warranted. Theme five implores the public and business sectors to collaborate with advocacy groups, professional organizations, educational institutions, HCOs, and private and nonprofit foundations to increase the number of nursing faculty. Nurse advocates and their allies can guide and position the public and business sectors in these broad collaborative efforts. This is the time to appeal to many various entities to meet societal responsibilities and to center collective justice as a common, desired endpoint (Muller et al., 2021). This call to action empowers the public and business sectors/business owners to use their bully pulpit collaboratively as agents of change and provides additional opportunities to elevate the human experience in healthcare.

Limitations and Strengths

While efforts were made to recruit a group of ANEs who were as diverse as possible, the use of convenience sampling limits generalizability of the findings from this NGT research process. However, the goal was not to generalize these findings to a wider population, but rather to gain a rich understanding of the intricacies in contributing factors to the dual nursing shortages and consider high-level solutions that stakeholders could implement.

This is the time to appeal to many various entities to meet societal responsibilities...

The NGT is time- and resource-intensive, thus attrition in sample size (from 45 to a final sample of 25) was not totally unexpected. Those who stayed were very invested and committed to this work. In keeping with the tenets of qualitative research, participants had ample opportunity to reflect on their own, and others, contributions, as they used multiple channels for clarification, correction, or challenge. For this NGT, personal knowledge and expertise were important guides for anecdotal evidence, which was subsequently carefully and intentionally checked against the published literature to add rigor to our methods. The modified NGT (i.e., virtual versus face-to- face) provided a meaningful and full experience for discussion.

Overall, the participatory action nature of the NGT approach strengthened the findings.

Implications

Implications for Research

Future research needs to include other key stakeholders beyond the ANE perspective. Regardless of the method for future research, it is important to remember that nursing is a human experience, accomplished in close relationship to others. Thus, studies guided by various methods will paint a more complete picture of the complex phenomena of the ANE shortage, the overall nursing shortage, and the resolution. This study can serve as a model for other nurse researchers to use to support change within the profession. The model demonstrates that partnerships and collaboration are key to allowing all stakeholders to provide the central and essential variables to a problem and to support solutions that satisfy and enhance each stakeholder’s need.

Implications for Practice and Education

All parties involved (e.g., students, faculty, and preceptors) need to collaborate to produce safe, equitable, and effective patient care. Both the academic environment and the practice environment need to appreciate and support all nursing personnel. The most valuable and enduring contributions will come from those in practice and education working together to build relationships The most valuable and enduring contributions will come from those in practice and education working togetherfounded on mutual respect and a common goal to produce more qualified nurses. Coalitions of nurses, including those employed primarily in education and those primarily in practice, along with students, can give compelling testimony to key stakeholders seeking to mitigate the overall shortage of practicing nurses and the shortage of faculty to teach new nurses.

The major take-home points from our study are:

- Working in concert, nurses and other leaders in both practice and education must work collaboratively to increase the nursing workforce in direct care and to increase the number of ANEs to educate novice nursing professionals.

- It is important to strengthen partnerships among leaders within nursing professional organizations, healthcare organizations, and educational institutions for the purposes of advancing care and increasing the nursing workforce, including nurses in direct care and those in ANE positions.

Our next steps include a Delphi study that is in progress to capture the evidence of specific changes that nurses desire and how to achieve those changes. The goals for the public and business sector, the consumers of healthcare, are to integrate research into care, advocate for improved patient safety, and increase the number of candidates interested in pursuing a nursing education.

Conclusions

The current nurse educator shortage has made a significant impact on both the public and business sectors. Counting nurses is necessary but not sufficient to effect change (Buerhaus, 2021). This project sought to move the needle beyond supply and demand through common targets of opportunity, such as academic-practice partnerships (Forcina et al., 2023), to a focus on the broader society to enlist the public and business sectors in the effort to address the shortage of ANEs.

It is essential that both sectors recognize this crisis as a priority that needs to be collectively addressed. We sought to answer our research question that considered solutions the public and business sectors/business owners could implement to address the shortage of academic nurse educators. The results provided the stakeholders with practical solutions, such as encouragement of members of the public sector to attend nursing education advocacy groups and providing templates for letters/emails for business owners to increase awareness about the shortage. These recommendations offer them a springboard to directly address the academic nurse educator shortage.

It is essential that both sectors recognize this crisis as a priority that needs to be collectively addressed.

If these recommendations/solutions are implemented, there is potential to improve retention and recruitment of ANEs. A continued partnership between the public/business sectors/business owners and leaders within the profession of nursing must exist in order to enhance the academic nurse educator role. Only with this partnership can those within the profession of nursing continue to serve the public sustainably for years to come.

Disclosure: The authors declare no actual or perceived conflicts of interest in the development of this project or dissemination of this manuscript.

Acknowledgement: The authors wish to extend their appreciation and gratitude to the members of the National Consortium of Academic Nurse Educators (NC-ANE) and those who participated in the nominal group technique method of the research: Edmund J. Y. Pajarillo, PhD, RN-BC, CPHQ, NEA-BC, ANEF, FAAN; Susan Siebold-Simpson, PhD, MPH, RN, FNP; Maria Bajwa, PhD, MBBS, MSMS, RHIT, CHSE; Jordan Baker, MSN, APRN, FNP-BC, CNE; Frederick Brown, DNP, RN, CENP; Suja P. Davis, PhD, RN; Jenneth B. Doria, DNP, MS, RN; Annemarie Dowling-Castronovo, PhD, RN, GNP-BC, ACHPN; Rachael Farrell, EdD, MSN, RN, CNE; Sheryl Feeney, MSN, RN, NPD-BC; Tracy Holt, DNP, RN-BC, CHSE, CNE; Edwin-Nikko R. Kabigting, PhD, RN, NPD-BC; Dulcinea M. Kaufman, DNP, RN, CNE; Valerie Esposito Kubanick, PhD, RN, PMH-BC; Jan L. Lee, PhD, RN; Janice Le Platte, MSN, MS, BSN, RN, NPD-BC; Laura Logan, MSN, RN, CCRN; Rae Mello-Andrews, MSN, MS, RN, RP; Kristi S. Miller, PhD, CPPS, CNE, RN; Jill M. Olausson, PhD, RN; Catherine Quay, MSN, RN-BC, CNE; Zelda Suzan, EdD, RN, CNE; Roseminda Santee, DNP, RN, NEA-BC, CNE, ANEF; Kelly Simmons, DNP, RN, CNE; Erica Sciarra, PhD, DNP, APN, AGNP-C, CNE; Shellye A. Vardaman, PhD, RN-BC, NEA-BC, CNE; Cynthia Wall, PhD, MSN, APRN, CNE; and Shari L. Washington, DNP, MSN, NPD-BC, CPN.

Authors

Jan L. Lee, PhD, RN

Email: jllhawkeye@gmail.com

Jan L. Lee earned a BSN at the University of Iowa, MN in medical-surgical nursing from UCLA, and PhD in higher, adult, and professional education from USC. She is currently a semi-retired nursing consultant/mentor. During her fulltime career, spanning 44 years, she was a staff nurse, patient care coordinator, clinical nurse specialist, nursing professor, and academic administrator. She held academic nursing positions in California, Michigan, Tennessee, and Iowa. She also was a nursing consultant to the RAND Corporation on quality of nursing care, and in 1994 helped start the first baccalaureate nursing program in Armenia.

Laura Logan, MSN, RN, CCRN

Email: lauralogan3@gmail.com

Laura Logan has over 30 years of experience as an RN in psychiatric and critical care areas. With over 18 years of experience as an academic instructor in a BSN program, she has taught (and coordinated) courses ranging from Fundamentals/Basic Care of Adults to Psychiatric Nursing and Critical Care Nursing. She has also taught online courses, such as family violence, history of the nursing profession, and processing grief. She has served on multiple national, state, college, and school committees and task forces related to nursing education and professional development.

Edmund J.Y. Pajarillo, PhD, RN-BC, CPHQ, NEA-BC, ANEF, FAAN

Email: pajarillo@adelphi.edu

Edmund J.Y. Pajarillo has been a nursing educator for over 25 years as faculty and educational administrator. His areas of expertise are the use of pedagogy and informatics to improve and innovate nursing education. Paramount among his many areas of professional service have been his contributions to the National League for Nursing.

Valerie A. Esposito Kubanick, PhD, RN, PMH-BC

Email: vespositokubanick@gmail.com

Valerie A. Esposito Kubanick earned her AAS from City University of New York, BS and MS in Nursing Administration from Adelphi University and PhD in Nursing with a cognate in Higher Education from Adelphi University. She is currently an Assistant Professor for the Nursing Department at York College, City University of New York. She has been teaching in higher education for over 18 years. Prior to her career in academia, her hospital experience included 17 years of experience in bedside nursing and administration. She is board certified in psychiatric-mental health nursing with her area of research in pain management in the substance use population.

Frederick Brown, Jr., DNP, RN, CENP

Email: Frederick_Brown@rush.edu

Frederick Brown has been a nurse for over 34 years. He completed his education at Rush University College of Nursing earning his DNP in 2007. He has served in the military as a Reservist and retired at the rank of Lieutenant Commander from the Navy Reserves after 22 years of service. He is currently the Director of Generalist Education for the MSN program at Rush University College of Nursing.

Edwin-Nikko R. Kabigting, PhD, RN, NPD-BC

Email: ekabigting@adelphi.edu

ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8590-8920

Edwin-Nikko R. Kabigting is an assistant professor at Adelphi University’s College of Nursing and Public Health. He earned a BSN, BA in philosophy, certificate in forensic health of adults, MS in Community Health Nursing, graduate certificate in advanced study in nursing education, and PhD in Nursing degrees from Binghamton University Decker College of Nursing and Health Sciences. A respected scholar in national and international arenas, he focuses on Parse’s humanbecoming paradigm. He is a fellow of the New York Academy of Medicine and currently serves as the Contributing Editor for Theoretical Concerns, as well as copyeditor for references, in the peer-reviewed journal, Nursing Science Quarterly.

Roseminda Santee, DNP, RN, NEA-BC, CNE, ANEF

Email: santee@ucc.edu

Roseminda Santee currently Dean of Trinitas School of Nursing/RWJ Barnabas Health in New Jersey, has been in nursing education for over 25 years. Trinitas has been an NLN Center of Excellence for continuously since 2008. Prior to her tenure in academia, she was a Director of Nursing for 13 years. She has prior service in the U.S. Army Nurse Corps, where she attained the rank of Major.

Jenneth B. Doria, DNP, MS, RN

Email: JENNETH.DORIA@nurs.utah.edu

Jenneth B. Doria is Associate Professor (Clinical) at the University of Utah College of Nursing. She was in nursing practice in diverse settings (e.g., infection prevention and control, mental health, same-day surgery, PACU, med-surg) for over 32 years. She later pursued MSN and DNP degrees to enhance her experience to prepare the future nursing workforce. Now a fulltime educator for over 8 years, she is a Fellow of the Academy of Health Science Educators and George Delores Eccles Foundation. An educator, business owner, and social entrepreneur, she presides over a 501c3 public foundation that supports the social determinants of health for the underserved in the Philippines.

Susan Seibold-Simpson, PhD, MPH, RN, FNP

Email: sseiboldsimpson@gmail.com

ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2417-9722

Susan Seibold-Simpson earned a BS (nursing) and MS in Family Nursing/Family Nurse Practitioner certificate from SUNY Binghamton, MPH from SUNY Albany, and PhD from the University of Rochester. Her program of research is sexuality and reproductive health and nursing education. She currently works part-time as a FNP at Southern Tier Women’s Health Services, LLC in Vestal, NY and as adjunct faculty at SUNY Delhi.

Maria Bajwa, PhD, MD, MSMS, RHIT, CHSE

Email: maria1bajwa@gmail.com

ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0962-5974

Maria Bajwa is a physician by background and works as a health professions educator at MGH Institute of Health Professions, Boston MA. She is a health professions and simulation educator, as well as a consultant and researcher in simulation and interprofessional education. She served as a technical research specialist for this project.

References

Aiken, L. (2007). U.S. nurse labor market dynamics are key to global nurse sufficiency. Health Services Research, 42(3), 1299-1320. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6733.2007.00714.x

Aiken, L. H., Sloane, D. M., McHugh, M. D., Pogue, C. A., & Lasater, K. B. (2023). A repeated cross-sectional study of nurses immediately before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for action. Nursing Outlook, 71(1), 101903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2022.11.007

Allen, J., Dyas, D. & Jones, M. (2013). Building consensus in health care: A guide to using the nominal group technique. British Journal of Community Nursing, 9(3). https://doi.org/10.12968/bjcn.2004.9.3.12432

American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2022). Nursing faculty shortage fact sheet. Retrieved from: www.aacnnursing.org/news-data/fact-sheets/nursing-faculty-shortage

American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2024). Graduate nursing student academy. Retrieved from: https://www.aacnnursing.org/students/gnsa

American Hospital Association (AHA). (2023, April 13). Study projects nursing shortage crisis will continue without concerted action. Retrieved from: https://www.aha.org/news/headline/2023-04-13-study-projects-nursing-shortage-crisis-will-continue-without-concerted-action

American Nurses Association (ANA) (2021). Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice (4 th ed.). ANA. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/scope-of-practice/

Atkins, B., Briffa, T., Connell, C., Buttery, A. K., & Jennings, G. L. R. (2023). Improving prioritization processes for clinical practice guidelines: New methods and an evaluation from the National Heart Foundation of Australia. Health Research Policy & Systems, 21(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-022-00953-9

Auerbach, D. I., Staiger, D. O., Muench, U., & Buerhaus, P. I. (2012). The nursing workforce: A comparison of three national surveys. Nursing Economic$, 30(5), 253–261.

Bakewell-Sachs, S., Trautman, D., & Rosseter, R. (2022). Addressing the nurse faculty shortage. American Nurse. Retrieved from: https://www.myamericannurse.com/addressing-the-nurse-faculty-shortage-2/

Berhe, D., Bewket, M. & Getachew, G. (2016). Why patients are dissatisfied in nursing care services at Menelik Hospital. Journal of Bio Innovation, 5(6), 850–860. Retrieved from: https://www.jbino.com/docs/Issue06_05_2016.pdf

Berkowitz, B. (2016). The patient experience and patient satisfaction: Measurement of a complex dynamic. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 21(1), Manuscript 1. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.3912/ojin.vol21no01man01

Beryl Institute (2024). Defining patient experience and human experience. https://theberylinstitute.org/new-to-patient-experience/

Buerhaus, P. (2021). Current nursing shortages could have long-lasting consequences: Time to change our present course. Nursing Economic$, 39(5), 247-250.

Buerhaus, P., Fraher, F., Frogner, B., Buntin, M., O’Reilly-Jacob, M., & Clarke, S. (2023). Toward a stronger post-pandemic nursing workforce. New England Journal of Medicine, 389(3), 200-203. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2303652

Coombs, N. C., Meriwether, W. E., Caringi, J., & Newcomer, S. R. (2021). Barriers to healthcare access among U.S. adults with mental health challenges: A population-based study.SSM - Population Health, 15,100847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100847

Forcina, J., Zomorodi, M., Morgan, L., & Barrington, N. (2023). Demonstrating a nurse-driven model for interprofessional academic-practice partnerships. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 28(2), ST Manuscript. https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol28No02ST02

Fox, R. & Abrahamson, K. (2009). A critical examination of the U. S. nursing shortage: contributing factors, public policy implications. Nursing Forum,44(4), 235-243. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6198.2009.00149.x

Griese, L., Berens, M., Nowak, P., Pelikan, J. M., & Schaeffer, D. (2020). Challenges in navigating the health care system: Development of an instrument measuring navigation health literacy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 5631. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165731

GovLoans.gov. (n.d). Nursing education loan repayment program. Retrieved from: https://www.govloans.gov/loans/nursing-education-loan-repayment-program/

Jarosinski, J., Seldomridge, L., Reid, T. & Willey, J. (2022). Nurse faculty shortage. Nurse Educator, 47(3), 151-155.https://doi.org/10.1097/NNE.0000000000001139

Johnson & Johnson. (2023). Our commitment to nurses. Retrieved from: https://nursing.jnj.com/our-commitment

Jonas Philanthropies. (2020). About us. Retrieved from: https://jonasphilanthropies.org/about-us-2/

Kalisch, B. (2016). Errors of omission: How missed nursing care imperils patients. American Nurses Association.

Kerfoot, K., & Buerhaus, P. (2022). Creating a nursing workforce needed to address the needs of society, employers, and nurses. Nursing Economic$, 40(6), 270-311.

Klein, H. E. (2023). How are healthcare organizations working on DEI efforts? American Journal of Managed Care. Retrieved from: https://www.ajmc.com/view/how-are-health-care-organizations-working-on-dei-efforts-

Manera, K;, Hanson, C.S., Gutman, T., & Tong, A. (2019). Consensus methods: Nominal group technique. In P. Liamputtong (Ed). Handbook of research methods in health social sciences. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_100

McElroy, A. (2023). New data show enrollment declines in schools of nursing, raising concerns about the nation’s nursing workforce. American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Retrieved from: https://www.aacnnursing.org/news-data/all-news/new-data-show-enrollment-declines-in-schools-of-nursing-raising-concerns-about-the-nations-nursing-workforce

Metersky, L., Rahman, R., & Boyle, J. (2023). Patient-partners as educators; Vulnerability related to sharing of lived experience. Journal of Patient Experience, 10, 1-4. https://doi.org/10.1177/23743735231183677

Mullen, R., Kydd, A., Fleming, A., & McMillan, L. (2021). A practical guide to the systematic application of nominal group technique. Nurse Researcher, 29(1), 14-20. https://doi.org/10.7748/nr.2021.e1777members.

Muller, R., Rach, C., & Salloch, S. (2021). Collective forward-looking responsibility of patient advocacy organizations: Conceptual and ethical analysis. BMC Medical Ethics, 22:113. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-021-00680-w

Nair, L., & Adetayo, O. A. (2019). Cultural competence and ethnic diversity in healthcare. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. Global Open, 7(5), e2219. https://doi.org/10.1097/GOX.0000000000002219

National Advisory Council in Nurse Education and Practice (NACNEP). (2022, January). Preparing nurse faculty, and addressing the shortage of nurse faculty and clinical preceptors. 17th report to the Secretary of Health and Human Services and the U.S. Congress. Retrieved from: https://www.hrsa.gov/sites default/files/hrsa/advisory-committees/nursing/reports/nacnep-17report-2021.pdf

National League for Nursing. (2022). NLN core competencies for academic nurse educators. Retrieved from: https://www.nln.org/nursing-education-competencies/core-competencies-for-nurse-educators

Ni Luasa, S., Ryan, N., & Lynch, R. (2023). A Systematic review protocol on workplace equality and inclusion practices in the healthcare sector. BMJ Open, 13(3), e064939. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-064939

Olsen, J. (2019). The nominal group technique (NGT) as a tool for facilitating pan-disability focus groups and as a new method for quantifying changes in qualitative data.International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18, 1-10.https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919866049

Teoli, D., Sanvictores, T., & An, J. (2022). SWOT Analysis. StatPearls[Internet] Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537302/

Udod S. (2023). A call for urgent action: Innovations for nurse retention in addressing the nursing shortage. Nursing Reports, 13(1), 145-147. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep13010015 Retrieved from: https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/expert-insights/nursing-faculty-shortage-in-the-us

U.S. Department of Labor (DOL). (2023, May 11). US DOL awards 78 million for nursing programs to strengthen, diversity workforce to fill quality jobs in 17 states. https://www.dol.gov/newsroom/releases/eta/eta202305110

Vardaman, S. A., Logan, L, Davis, S. P., Sciarra, E, Doria, J. B., Baker, J., Feeney, S., Pajarillo, E. J. Y., Seibold-Simpson, S. & Bajwa, M. (2024). Addressing the shortage of academic nurse educators: Recommendations for educational institutions based on nominal group technique research. Nursing Education Perspectives. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NEP.0000000000001264

Wallach, L. (1994). Media advocacy; A strategy for empowering people and communities.Journal of Public Health Policy, 15(4), 420-436.

Wasim, A., Sajan, M., & Majid, U. (2023). Patient-centered care frameworks, models and approaches: An environmental scan, Patient Experience Journal, 10(2), 14-22.

Wolf, J.A. (2022). Human experience is not a line item. Patient Experience Journal, 9(2), 1-3. https://doi.org/10.35680/2372-0247.1746

Wolf, J.A., Niederhauser, V., Marshburn, D., & LaVela, S.L. (2014). Defining patient experience. Patient Experience Journal, 1(1), 7-19. https://doi.org/10.35680/2372-0247.1004