Nurses interact with a variety of healthcare professionals, including fellow nurses, as part of day-to-day practice. Nurse-to-nurse relationships are an area of concern due to their impact on patient, nurse, and organizational outcomes. Though nursing connections and issues occur across the practice spectrum, there is a focus on newly licensed professionals. However, experienced nurses also struggle with nurse-to-nurse relationship issues as they transition from one clinical specialty to another. There is a lack of literature that addresses transitions for this population. Thus, nurses may be ill-prepared to recognize challenges and support healthy nursing relationships and beneficial work environments. This article discusses challenges faced by experienced nurses and offers strategies to support healthy nurse-to-nurse relationships during the transition to new clinical specialties. Nurses, including formal and informal leaders, peers, and individuals transitioning to new specialties, must assess and acknowledge, make individualized plans, and promote positive spaces to support nursing relationships, work environments, and outcomes.

Key Words: experienced nurses transition to new specialty; healthy work environments for nurses; nurse-to-nurse collaboration; nurse orientation or onboarding; nursing leadership; nursing professional development; patient outcomes; relationships; relationship building; work environments in nursing

Nursing relationships have healthy and unhealthy elements and can change over time.Nurses interact with many kinds of healthcare professionals as a part of day-to-day practice. In addition to interdisciplinary professionals, these individuals include other nurses with varying levels of authority and/or experience. Professionals typically include informal leaders, such as experienced nurses and preceptors, and formal leaders, such as charge nurses, nurse managers, assistant nurse managers, and professional development specialists. Additionally, nurses frequently interact with nursing peers. As they interact with various colleagues, nurses develop connections with unique aspects, benefits, and challenges. Nursing relationships have healthy and unhealthy elements and can change over time. Healthy relationships in healthcare build teams, increase collaboration, and strengthen effective communications (Institute for Safe Medication Practices, 2021); thus professional relationships heavily influence work environments.

One key strategy for creating and maintaining healthy work environments involves improving nursing relationships.Healthy work environments in healthcare involve effective communication, decision-making, and collaboration, appropriate staffing, meaningful recognition, and authentic leadership (Woolforde, 2019). Although each element is important, most require healthy relationships. Violations of the healthy work environment are common and frequently involve relationship problems, including incivility, bullying, harassment, intimidation, and other disruptive behaviors (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2022; Chao et al., 2021; Nouri et al., 2019; The Joint Commission, 2021). Fortunately, as populous and frontline healthcare workers, nurses are well-poised to confront these issues. One key strategy for creating and maintaining healthy work environments involves improving nursing relationships (Nouri et al., 2019). Understanding and strengthening nurse-to-nurse relationships is essential as fast-paced and ever-changing environments compound issues and threaten adverse outcomes (Crawford et al., 2019).

Background

Transitions increase stress through already difficult times, which can further negatively impact nurse-to-nurse relationships.Although nurse-to-nurse relationships are important to consider through the lens of daily practice, relationships are particularly strained during periods of transition (Crawford et al., 2019; McGuire, 2020; Newman, 2019). Transitions increase stress through already difficult times, which can further negatively impact nurse-to-nurse relationships. Transitioning nurses may include those across the practice spectrum, such as newly licensed professionals and experienced nurses transitioning to new clinical specialties and settings. Experienced nurses transitioning to new clinical specialties could include nurses who are moving to permanent positions or travel nurses on temporary assignments in areas of need. Despite universality, the available literature tends to focus on transitions of newly licensed nurses, including the struggles these professionals face and ways to improve transitions and relationships. For example, many authors explore how ‘nurses eat their young.’

Despite the literature focus on newly licensed nurses, seasoned professionals also experience difficulties in nursing relationships.Despite the literature focus on newly licensed nurses, seasoned professionals also experience difficulties in nursing relationships. Some authors discuss the distinct challenges and issues experienced nurses face as they transition and have noted that the needs of these nurses are frequently overlooked (Chicca, 2021; Chicca & Bindon, 2019). This lack of attention is especially concerning, given nurses regularly transition clinical specialties. In recent years, many factors have increased the prevalence of experienced nurses moving to new clinical practice areas. In Guttormson et al.’s (2022) national study, many participants cited inadequate staffing during the pandemic as a key reason they transitioned from critical care settings. Nurses frequently search for new opportunities that allow them to contribute to the nursing profession in a way that best suits them. For example, nurses may seek slower-paced positions that match their existing or desired skillsets. They might seek additional compensation and flexibility. However, as they transition to new specialties, seasoned nurses experience numerous difficulties, including the predominant concerns of unhealthy relationships and detrimental work environments.

Unhealthy relationships and work environments negatively impact patient, nurse, and healthcare facility outcomes. First, poor communication among healthcare professionals is cited as a leading cause of medical errors and sentinel events which leads to short-term harm, long-term harm, or even patient deaths (Jones et al., 2019). Inappropriate behaviors also cause healthcare professionals to not function as a team, which further compounds patient safety concerns. Unhealthy relationships may lead nurses to perceive the work environment negatively, which means these nurses might feel isolated, ignored, stressed, and burnt out, impacting their cognition, clinical judgment, and performance (ANA, 2022; Nouri et al., 2019).

These issues can lead to absenteeism, lost productivity, and turnover, which may increase organizational costs.In addition to these issues impacting patients, many nurses will experience physical symptoms (e.g., low energy, headaches, frequent illnesses, chest pain) and/or psychological distress (e.g., burnout, anxiety, depression, forgetfulness). These issues can lead to absenteeism, lost productivity, and turnover, which may increase organizational costs. Subsequently, facilities often spend considerable time, money, and resources recruiting and training new hires. Supervising uncivil behaviors is also a source of cost to organizations (ANA, 2022). Nurse managers can spend time documenting inappropriate employee behaviors and they may spend time coaching a problematic staff member.

To facilitate positive outcomes, nurses across the practice spectrum can nurture healthy nurse-to-nurse relationships, setting the tone and continuing to monitor work environments (Crawford et al., 2019). Nurses must role model appropriate behaviors and work to continuously address inappropriate behaviors as a shared responsibility (Nouri et al., 2019). However, the lack of literature around experienced nursing transitions and relationship concerns may mean that nurses may not fully understand issues or how best to support this population. This article discusses challenges and offers strategies for nurses as they support healthy nursing relationships, improve work environments, and enhance healthcare outcomes.

Challenges as Experienced Nurses Move to New Clinical Specialties

Multifaceted, complex issues impact experienced nurses as they move to new specialties. As they transition to new specialties, experienced nurses confront complex emotions, face learning gaps, struggle with unlearning, sense threats to their identities, and work to adapt to new colleagues and surroundings.

Experienced nurses have various complex emotions as they move to new clinical specialties.Experienced nurses have various complex emotions as they move to new clinical specialties. The transitioning nurse might feel excited, hopeful, afraid, stressed, anxious, guilty, exhausted, overwhelmed, and embarrassed (Chicca, 2021; Jeffery et al., 2018; McGuire, 2020). A professional who transitions from critical care to ambulatory practice may feel excited and hopeful for the new position, yet may also feel anxious, tense, stressed, and overwhelmed. Nurses can even feel guilty if they left their former colleagues without adequate staffing. Nurses might question their abilities and decision to move to new practice areas (Chicca, 2021). As a result of these complex feelings, nurses could unintentionally react negatively when interacting with a colleague, such as being short with a peer. Nurses struggling with their emotions may not receive intended messages. Professionals may perceive interactions poorly, or they may not have the capacity to listen to communications given their current state.

Complex emotions are heightened as nurses confront gaps in their knowledge, skills, and abilities while they work to unlearn previous information and prior habits. Specific competencies that nurses must learn vary, but may include intravenous (IV) insertion and care, common diagnoses and typical nursing care, early signs and symptoms of decompensation, specialty-specific prioritization, scope of practice, and medical record use (Chicca, 2021). Benner’s From Novice to Expert theory illustrates this phenomenon by discussing skill acquisition during a nurse’s career (1982, 1984). When experienced nurses transition to new clinical specialties, they can revert to an earlier stage of Benner’s theory and once again are situated as novices or advanced beginners. Reverting to an earlier stage can be upsetting for the experienced nurse. The amount nurses must learn depends on the transition itself. Regardless, experienced nurses frequently feel overwhelmed, making it challenging to learn and retain new knowledge, skills, and abilities as well as unlearn prior competencies (Chicca, 2021; Ulrich, 2019).

Reverting to an earlier stage can be upsetting for the experienced nurse.Additionally, personal life events can complicate nursing transitions, such as changing locations or altering personal relationships (e.g., marriage, divorce). Personal life events often increase the nurse’s stress, diminishing the ability to learn and cooperate with others (Chicca, 2021). Nurses must also unlearn and, at times, may feel trapped in their old ways or that they are in a new world (Chicca, 2021; Newman, 2019). These issues may cause nurses to feel threats to their identities.

As experienced nurses move to new practice areas, they often feel the need to prove that they are skilled professionals who can succeed in new environments. Chicca (2021) reported that experienced nurses take pride in their identities as skilled clinicians and enjoy being resources to others. However, as they move to new clinical specialties, their professional identity is threatened, often leaving them to feel lumped in with newer nurses. They may feel that their prior experiences are not valued, and instead, they could feel unaccepted, watched, unfairly critiqued, and ostracized (Chicca, 2021; Kinghorn et al., 2017). Such feelings can lead to relationship issues. An experienced nurse may offer advice to a colleague, but a newer nurse may reject suggestions because the nurse recently joined the clinical unit. The suggestion may make the newer nurse feel insecure, anxious, or the need to prove abilities, potentially belittling the seasoned nurse in the process. Townsend (2016) refers to such scenarios as the ‘super nurse’ phenomenon, where nurses feel the need to draw attention to their own abilities and raise themselves up, while demeaning others. Nurses could even feel defensive if others do not accept their offers for help (Chicca, 2021). Such negative interactions can harm relationships between newer nurses and experienced professionals, causing temporary or permanent damage. Distrust, resentment, and isolation may interfere with the ability to function as a team.

...as they move to new clinical specialties, their professional identity is threatened, often leaving them to feel lumped in with newer nurses.In addition to complex emotions, difficulties learning and unlearning, and feeling identity threats, experienced nurses moving to new specialties also interact with unfamiliar people and practice in new areas. Whether colleagues are supportive (or not), and surroundings are nurturing (or not), adapting to a new environment is challenging (Chicca, 2021). Understanding the actions and behaviors of others, as well as norms, requires time and effort. One nurse may tease others to show affection, whereas another individual may taunt someone to test the nurse’s strength. Additionally, unwritten rules and/or chains of command may not be known to an outsider (e.g., not contacting the supervising physician after hours). Adaptations challenge the transitioning nurse and, again, can cause damage to professional relationships and team functioning.

Similar to the phenomenon of ‘nurses eating their young’ related to new graduates, seasoned nurses can experience incivility until they have ‘paid their dues,’ so to speak. In Chicca’s (2021) study, one nurse described an invisible marker in a new clinical unit; only after two years was the nurse taken seriously and treated kindly. If only certain colleagues are supportive, experienced nurses may regularly engage only with particular staff on the unit (Kinghorn et al., 2017). Selecting particular staff members to assist in times of need is a potentially dangerous practice because selected staff may not be available or have the most situation-specific knowledge during times of need or crisis. It may also take time for nurses to know the best colleague with whom to consult in a particular situation. It is difficult to meet the needs of patients and facilities without having aspects of healthy nursing relationships, such as rapport. Selective relationships can perpetuate a cycle of incivility, which impedes the building of healthy relationships in organizations and in nursing units.

Supporting Healthy Nurse-to-Nurse Relationships

Supporting healthy nurse-to-nurse relationships is a shared responsibility, especially in times of transition.Supporting healthy nurse-to-nurse relationships is a shared responsibility, especially in times of transition. Meticulous attention and monitoring of clinical settings ensures healthy work environments. To strengthen healthy relationships, professionals should 1) assess and acknowledge, 2) make individualized plans, and 3) promote positive spaces. A multifaceted approach is recommended; however, nurses should prioritize the issues while considering needs and organizational resources. While using strategies, nurses can select appropriate methods per strategy, testing their effectiveness and making changes on an ongoing basis. A holistic, critical approach helps to ensure success.

Assess and Acknowledge

Supporting healthy nurse-to-nurse relationships should first involve ongoing self-assessments by each nurse. Whether they are aware or not, many nurses hold biases regarding experienced nurses, such as preconceptions around existing knowledge, skills, abilities, and/or attitudes. These biases may be positive or negative in nature and both are issues that should be addressed. A nurse manager may assume the experienced nurse has a basic understanding of the disease processes commonly found on the unit, or they could assume the nurse can complete certain skills, such as inserting an IV line and administering medications. The nurse preceptor could feel that experienced nurses may be too proud to ask questions and instead will try to figure things out independently without any assistance. In reality, nurses may not possess certain knowledge, skills, and abilities, and they may regularly speak up when they need assistance. Nurses should first assess their own biases and work to set them aside to help colleagues as they transition to new clinical specialties.

Supporting healthy nurse-to-nurse relationships should first involve ongoing self-assessments by each nurse.Nurses should conduct honest self-appraisals daily, paying careful attention to thoughts and feelings. As they begin these appraisals, written or electronic journals can remind nurses to complete this task and help them to see biases and patterns. Electronic applications (e.g., Microsoft OneNote) can securely record and store reflections. Nurses could also jot down counterpoints in their journals to recognize and mitigate biases. Professionals may determine that biases are based upon limited interactions or remind themselves that not everyone responds to change similarly, nor do nurses have the exact same experiences. Reflection holds biases at the forefront and is helpful to view a particular situation, to support each individual’s professional development needs.

Next, nurses should assess their colleagues’ current feelings as well as their knowledge, skills, and abilities (Chicca, 2019). Assessment efforts could involve a formal conversation or questionnaire, or an informal assessment. A staff development professional may start a nurse’s orientation with a one-to-one formal meeting, asking various questions and having the nurse complete a checklist or questionnaire. Additional examples are provided in the Table.

Table. Strategies to Support Healthy Nurse-to-Nurse Relationships

|

Strategy |

Examples |

|---|---|

|

Assess and acknowledge (Chicca, 2019; Chicca, 2021; Chicca & Shellenbarger, 2020; Jeffery et al., 2018) |

|

|

Make individualized plans (Boyer et al., 2018; Chicca, 2021; Chicca & Shellenbarger, 2020; Crawford et al., 2019; Hubbard & Chicca, 2022; Jeffery et al., 2018; Ulrich, 2019) |

|

|

Promote positive spaces (Chicca & Shellenbarger, 2020; Crawford et al., 2019; Hubbard & Chicca, 2022; Jeffery et al., 2018; Jones et al., 2019; Kinghorn et al., 2017; Townsend, 2016; Woolforde, 2019) |

|

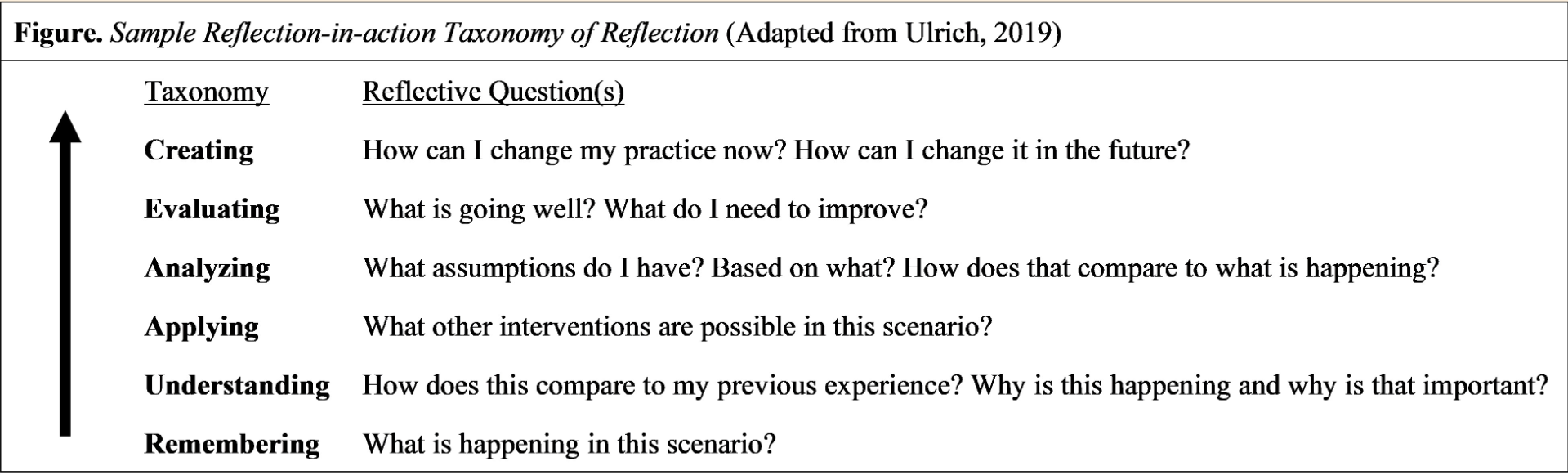

Note. *See the Figure for an example reflection-in-action Taxonomy of Reflection.

Nurse leaders and colleagues should watch for potential issues as experienced nurses move to new specialties. Jeffery et al. (2018) warned of red flags in the first few days of employment, including a) displaying atypical emotions (e.g., complete silence, constant crying), b) taking frequent breaks, c) verbalizing dissatisfaction with the new position, and d) gross incompetence or carelessness. These red flags warrant immediate intervention, including temporary or permanent removal from the clinical setting.

Recognizing complex emotions, learning curves, and other struggles that they face helps the nurse feel welcomed and appreciated.While assessing the experienced nurse, it is important to acknowledge others, and what they are experiencing. Recognizing complex emotions, learning curves, and other struggles that they face helps the nurse feel welcomed and appreciated. Acknowledging new hires involves engaging with the professional daily by directly telling them that they are welcome and appreciated (Chicca, 2021; Chicca & Shellenbarger, 2020; Jeffery et al., 2018). Acknowledging prior experiences also helps the seasoned nurse feel valued. Role modeling such behaviors sets the stage for other staff to follow suit, improving nurse-to-nurse relationships. The Table offers example statements and behaviors to role model.

The practice of social talk may enhance group cohesion, teamwork, and a willingness to stay in one’s position.Chao et al. (2021) mentioned the significance of social talk in practice environments while developing interpersonal relationships. The authors found that nurses most often spoke to one another regarding tasks and provided little emotional support. The practice of social talk may enhance group cohesion, teamwork, and a willingness to stay in one’s position (Chao et al., 2021). Therefore, nurses should role model brief social talks with colleagues. Before the morning huddle, nurses could ask individuals about their past time off or future plans. After assessing and acknowledging the seasoned nurse, individualized plans are needed to promote healthy nurse-to-nurse relationships.

Make Individualized Plans

As with newly licensed professionals, experienced nurses also need individualized guidance and support as they move to new specialties through orientation processes. A proper onboarding process can help achieve positive outcomes (Jeffery et al., 2018) and involves providing various external supports and cultivating internal reserves (Chicca, 2021). Considerations for experienced nurses moving to new clinical specialties, specifically related to supporting nurse-to-nurse relationships, are offered next.

It is important to share unwritten rules and chains of command.First, basic housekeeping orientation encourages healthy nurse-to-nurse relationships by reducing stress and socializing nurses in their new areas (Jeffery et al., 2018). A nurse preceptor can familiarize the nurse with the physical space and people in the practice environment as well as review formal policies and procedures. It is important to share unwritten rules and chains of command. Revisiting the earlier example, a charge nurse may share that the supervising physician is typically not paged after hours. Staff could create and maintain ‘cheat sheets’ to share with new hires as they become familiar with the environment.

Nurses should share resources to help others succeed. These resources could include people, reference materials, and internal programs or offerings external to the clinical organization. Nurses should be clear on when, where, and how they can get help (Chicca & Shellenbarger, 2020). Orientation topics depend on prior knowledge, skills, and abilities. A nurse hired internally may be aware of facility policies, whereas someone hired externally may need a more extensive policy review. Individualized offerings promote success, prevent wasting time and resources, and support healthy nursing relationships.

Exact supports depend on nurses’ needs and facility offerings, but it is essential to individualize plans.Next, nurses need to clearly delineate what structured external supports the nurse will experience, as well as any potential struggles the nurse may have with the move to a new setting. Examples of structured supports are one-to-one time with a preceptor, a mentor, and a structured transition program. Exact supports depend on nurses’ needs and facility offerings, but it is essential to individualize plans. Careful preceptor pairings or team approaches to precepting may best support the seasoned nurse (Jeffery et al., 2018; Ulrich, 2019). Preceptors who have made similar transitions in the past or who frequently orient experienced nurses may be an ideal match as they likely understand what the orientee is experiencing and how best to help them (Chicca, 2021; Crawford et al., 2019; Ulrich, 2019). Team approaches to precepting expose transitioning nurses to multiple colleagues and shows them new ways of thinking and completing nursing tasks. Exposure to multiple colleagues during the orientation period helps nurses learn information, unlearn prior habits, and cultivates their relationships with new colleagues.

Nurses may need to design structured transition programs at facilities, if they do not already exist. Existing offerings for newly licensed nurses can serve as a basis, but it is important to incorporate issues that experienced nurses endure with consideration of previous and current knowledge, skills, and abilities. Boyer et al. (2018) suggested coaching plans to address competency deficiencies, considering what is needed for practice areas. Training materials and ways to assess proficiency should be outlined based on essential competencies. Emergency room nurses could develop competency checklists regarding common procedures, whereas an ambulatory practice may need to teach nurses about their scope of practice in the new setting and how to triage calls. A structured framework, such as the ADDIE (i.e., analyze, design, develop, implement, evaluate) model, can guide ongoing efforts to create and maintain transition programs (Jeffery et al., 2018).

Creativity and resource-sharing can assist nurses to develop meaningful programs with limited resources. Jeffery et al. (2018) referred to this as “champagne programs on a beer budget” (p. 6). Nurses can reach out to other departments, reuse existing content, and consider low-tech offerings. The supply department of the organization may have resources that are no longer safe for patient use (e.g., expired products) and these items could be utilized for training (Jeffery et al., 2018).

Travel nurses require additional consideration when developing transition programs. Travel nurses receive short orientation periods and are frequently expected to hit the ground running. However, these seasoned nurses still warrant attention. Abbreviated offerings that focus on any essential knowledge, skills, and abilities are recommended (Jeffery et al., 2018). Considerations about 1) what the travel nurse is required to do, and 2) what they must know to be successful can guide succinct, organized, and supportive, yet shortened, orientations. After orientation, nurse leaders should select patient care assignments to ensure that responsibilities match travel nurses’ skill sets and that assignments are safe.

Internal resources are a continuous way to reduce stress for experienced nurses transitioning into new fast-paced, strenuous, and changing specialties.In addition to supporting healthy nurse-to-nurse relationships through structured external support, leaders should develop nurses’ internal reserves. Internal resources are a continuous way to reduce stress for experienced nurses transitioning into new fast-paced, strenuous, and changing specialties. First, staff should help nurses resolve conflicts appropriately; this will help current and future relationships as well as positively impact patient outcomes. Nurses should role model and coach respectful techniques to address conflicts, which maintains healthy relationships. The two-challenge rule is a method to respectfully disagree with another nurse. A concerned professional can politely repeat the concern twice or ask for a second person’s input (Hubbard & Chicca, 2022). Or, nurses can remember the acronym CUSS: stating a Concern, saying they are Uncomfortable, citing Safety, and requiring a Stop in activities until the issue is resolved (Hubbard & Chicca, 2022).

Another vital aspect of conflict resolution involves understanding others’ perspectives.Another vital aspect of conflict resolution involves understanding others’ perspectives. Crawford et al. (2019) cited the three sides to every story (i.e., your version, my version, and the truth) and emphasized the importance of getting to the root of the issue versus taking sides. Townsend (2016) recommended using ‘I statements’ when discussing an issue, focusing on objectively observed behaviors and safety. The Table delineates sample ‘I statements.’ Disagreements are unavoidable, but understanding multiple perspectives and concentrating on facts supports healthy relationships.

In addition to role modeling and coaching conflict resolution techniques, nurses can use reflection abilities and coping skills to reduce stress and improve relationships. The constant learning, unlearning, and pressure to prove themselves weighs on the experienced nurse. A deliberate, reflective process helps nurses work through these tasks, reducing their stress and improving nursing relationships (Chicca, 2021; Kinghorn et al., 2017; Newman, 2019; Townsend, 2016; Ulrich, 2019). Structures, like the Taxonomy of Reflection (Ulrich, 2019) could help nurses coach others through this process. A sample Taxonomy of Reflection is presented in the Figure.

Coping skills include self-care activities, such as exercising, getting enough sleep, taking regular breaks as well as mindful practices like active listening, focused breathing in small bursts for concentration, and taking short walks during scheduled break times. Coping skills can be integrated into existing professional development offerings (Woolforde, 2019). A course outlining clinical topics may start with a brief mindfulness session or a short lesson on self-care, or new offerings can be created. Jones et al. (2019) found the course Communication Under Pressure positively impacted relationships and perceptions of the work environment.

Nurses who are particularly skilled at communicating with patients may use that ability to help them in their new areas.Nurses should encourage others to draw on their own strengths, including previous experiences, a willingness to learn, and enjoyment they might find in their new positions (Chicca, 2021). Nurses who are particularly skilled at communicating with patients may use that ability to help them in their new areas. A nurse with critical care experience might use assessment skills to evaluate a patient who has fainted in an outpatient setting. Nurses have many strengths from which to draw as they move to new positions.

Individualized plans help experienced nurses transition to new clinical specialties. Work environments must also support these programs to ensure success. The next section presents methods for promoting positive spaces.

Promote Positive Spaces

Organizational culture, staff actions, and their inactions may influence the intent to stay in current positions...Organizational culture, staff actions, and their inactions may influence the intent to stay in current positions; thus, it is essential that nurses promote positive spaces to support nurse-to-nurse relationships. Work environments with zero-tolerance for violations decrease the physical and emotional burdens of the transitioning staff and improve patient, nurse, and facility outcomes (Crawford et al., 2019; Jeffery et al., 2018; Kinghorn et al., 2017; Townsend, 2016). Swiftly addressing overt (i.e., obvious intent to harm) and covert (i.e., hidden intent to harm) acts of incivility is essential.

Clear-cut policies, procedures, and infrastructures guide nurses in their efforts to create and maintain a positive space.Staff will notice if acts of incivility are not handled each and every time. Incivility actions can include a senior staff member subtly rolling their eyes at a new hire or gossiping about the new hire to other staff members. The Table outlines further examples. Noticing acts of incivility results in needed interventions, such as private conversations and disciplinary actions. How discrimination is dealt with by administrators and others heavily impacts a professional’s experience and perceptions of the work environment (Chicca & Shellenbarger, 2020). Clear-cut policies, procedures, and infrastructures guide nurses in their efforts to create and maintain a positive space (Crawford et al., 2019).

In addition to a zero-tolerance atmosphere, nurse professionals who role model and require others to use judgement-free communication promote positive spaces (Hubbard & Chicca, 2022). Nurses can ask the preferred name for an experienced nurse. When noting an issue, a nurse should stick to outlining any observations of behavior and proposing alternatives while acknowledging the experienced nurse and their role and expertise. Nurses should use a calm, even tone of voice, with an open posture and positive body language, such as eye contact and head nodding (Chicca & Shellenbarger, 2020; Hubbard & Chicca, 2022). Nurses have to emphasize patient safety and the fact that they value the distinctive contributions of the experienced nurse. These efforts decrease the chance that a nurse will be offended, supporting positive relationships between nurses.

Professional development offerings and resources also support continued personal growth (Crawford et al., 2019). In-services and other offerings can teach nurses about covert and overt signs of relationship issues, how to support colleagues, and organizational policies. Although existing orientation, training, or staff meeting times can convey this information, additional and specialized offerings might be needed for nurses in formal and informal leadership roles, such as staff development specialists, charge nurses, nurse managers, assistant nurse managers, and preceptors.

Professional development offerings and resources also support continued personal growth.Nursing staff resources, including employee assistance programs and reporting hotlines, are also recommended (Crawford et al., 2019). These additional resources help nurses on a day-to-day basis. An employee assistance program could be used by seasoned nurses who are particularly stressed, or the nurses can report relationship concerns via hotlines (e.g., phone line for live or recorded calls and text messages, email addresses). Staff resources cultivate positive spaces that promote healthy relationships.

Knowledge surrounding experienced nurses is still emerging. An ongoing assessment of nurses’ own biases, knowledge, skills, and abilities, as well as a continuous appraisal of the environment, is critical to elicit and sustain change. This article offered strategies to start these needed improvements. In assessing and acknowledging, making individualized plans, and promoting positive spaces, nurses can enhance nurse-to-nurse relationships, sharing the responsibility to promote healthy work environments and positively impact patients, nurses, and organizations.

Conclusion

These concerns can threaten adverse outcomes, and impact mental health and intent to stay.Despite focus on the transition of newly licensed professionals, experienced nurses also confront nurse-to-nurse relationship issues while transitioning to new specialties. As experienced nurses endure many complex emotions, face learning gaps, struggle with unlearning, sense threats to their identities, and work to adapt to new colleagues and surroundings, they encounter several relationship and environmental issues. These concerns can threaten adverse outcomes, and impact mental health and intent to stay. Nurses share the responsibility to create healthy work environments and support positive professional relationships. Ultimately, healthy workplaces enhance patient, nurse, and organizational outcomes.

Authors

Jennifer Chicca, PhD, RN, CNE, CNEcl

Email: jchicca@nln.org

ORCID ID: 0000-0003-0490-9601

Jennifer Chicca is the Deputy Director, National League for Nursing Commission for Nursing Education Accreditation, Washington, DC, and Part-Time Faculty in the MSN Nurse Educator Program, College of Health and Human Services, School of Nursing, University of North Carolina Wilmington, Wilmington, NC.

Hope Hubbard, MSN, RN, CEN

Email: hhubbard@wakemed.org

Hope Hubbard is a Nursing Professional Development Specialist at WakeMed Health and Hospitals in Raleigh, NC.

References

American Nurses Association. (2022). Incivility, bullying, and workplace violence. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/official-position-statements/id/incivility-bullying-and-workplace-violence/

Benner, P. (1982). From novice to expert. The American Journal of Nursing, 82(3), 402-407. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000446-198282030-00004

Benner, P. (1984). From novice to expert: Excellence and power in clinical nursing practice. AJN, American Journal of Nursing 84(12), 1479, December 1984. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000446-198412000-00025

Boyer, S. A., Mann-Salinas, E. A., & Valdez-Delgado, K. K. (2018). Clinical transition framework: Integrating coaching plans, sampling, and accountability in clinical practice development. Journal for Nurses in Professional Development, 34(2), 84-91. https://doi.org/10.1097/NND.0000000000000435

Chao, L-F., Guo, S-E., Xiao, X., Luo, Y-Y., & Wang, J. (2021). A profile of novice and senior nurses’ communication patterns during the transition period: An application of the Roter Interaction Analysis System. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 10688. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010688

Chicca, J. (2019). The new-to-setting nurse: Understanding and supporting clinical transitions. American Nurse Today, 14(9), 22-25. https://www.myamericannurse.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/ant9-Clinical-transitions-829.pdf

Chicca, J. (2021). Weathering the storm of uncertainty: Transitioning clinical specialties as an experienced nurse. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 52(10), 471-481. https://doi.org/10.3928/00220124-20210913-07

Chicca, J., & Bindon, S. (2019). New-to-setting nurse transitions: A concept analysis. Journal for Nurses in Professional Development, 35(2), 66–75. https://doi.org/10.1097/NND.0000000000000530

Chicca, J., & Shellenbarger, T. (2020). Fostering inclusive clinical learning environments using a psychological safety lens. Teaching and Learning in Nursing, 15, 226-232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.teln.2020.03.002

Crawford, C. L., Chu, F., Judson, L. H., Cuenca, E., Jadalla, A. A., Tze-Polo, L., Kawar, L. N., Runnels, C., & Garvida, R. (2019). An integrative review of nurse-to-nurse incivility, hostility, and workplace violence: A GPS for nurse leaders. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 43(2), 138-156. https://doi.org/10.1097/NAQ.0000000000000338

Guttormson, J. L., Calkins, K., McAndrew, N., Fitzgerald, J., Losurdo, H., & Loonsfoot, D. (2022). Critical care nurses’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic: A US national survey. American Journal of Critical Care, 31(2), 96-103. https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2022312

Hubbard, H., & Chicca, J. (2022). Navigating authority gradients. American Nurse Journal, 17(1), 44-47. https://www.myamericannurse.com/navigating-authority-gradients/

Institute for Safe Medication Practices. (2021). Disrespectful behavior in healthcare: Has it improved? https://www.ismp.org/resources/disrespectful-behavior-healthcare-has-it-improved-please-take-our-survey

Jeffery, A. D., Jarvis, R. L., & Word-Allen, A. J. (2018). Staff educator’s guide to clinical orientation: Onboarding solutions for nurses (2nd ed.). Sigma Theta Tau International.

Jones, L., Cline, G. J., Battick, K., Burger, K. J., & Amankwah, E. K. (2019). Communication under pressure: A quasi-experimental study to assess the impact of a structured curriculum on skilled communication to promote a healthy work environment. Journal for Nurses in Professional Development, 35(5), 248-254. https://doi.org/10.1097/NND.0000000000000573

Kinghorn, G. R., Halcomb, E. J., Froggatt, T., & Thomas, S. D. M. (2017). Transitioning into new areas of clinical practice: An integrative review of the literature. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26, 4223-4233. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14008

McGuire, T. (2020). Experienced nurses transition to practice. Journal for Nurses in Professional Development, 36(6), 355-358. https://doi.org/10.1097/NND.0000000000000671

Newman, M. B. (2019). Unlearning: Enabling professional success in an ever-changing environment. Professional Case Management, 24(5), 262-264. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCM.0000000000000382

Nouri, A., Sanagoo, A., Jouybari, L., & Taleghani, F. (2019). Challenges of respect as promoting healthy work environment in nursing: A qualitative study. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 8, 261. https://10.4103/jehp.jehp_125_19

The Joint Commission. (2021). Quick safety issue 24: Bullying has no place in healthcare. https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/news-and-multimedia/newsletters/newsletters/quick-safety/quick-safety-issue-24-bullying-has-no-place-in-health-care/#.YwpwdnbMKM-

Townsend, T. (2016). Not just “eating our young”: Workplace bullying strikes experienced nurses, too. American Nurse Today, 11(2), 1. https://www.myamericannurse.com/just-eating-young-workplace-bullying-strikes-experienced-nurses/

Ulrich, B. (2019). Mastering precepting: A nurse’s handbook for success (2nd ed.). Sigma Theta Tau International.

Woolforde, L. (2019). Beyond clinical skills: Advancing the healthy work environment. Journal for Nurses in Professional Development, 35(1), 48-49. https://doi.org/10.1097/NND.0000000000000510