Results from National Impact Assessment (NIA) surveys conducted by the American Nurses Association during the COVID-19 pandemic revealed a nursing profession in distress. National nurse respondents from all employment settings reported stress, with bullying and violence at work, most commonly caused by patients and families. Greater than 50% of national respondents were considering or planning to leave their nursing position within the next six months. These alarming findings prompted leaders of one of the ANA’s midwestern affiliates in Kentucky to launch a state-wide survey that explored perceptions of nurses living or working in the state (n = 850) regarding possible contributors to the nursing shortage, and supportive actions to alleviate them at the time of a significant nursing shortage during the COVID-19 pandemic. Data collected by KNA researchers were also compared against the NIA database to determine if differences existed between Kentucky’s state-specific data and national trends. While some of the highest rated contributors to the nursing shortage concerned insufficient staffing and pay, most of the top-rated concerns expressed by KY nurses related to lack of support for nurses and lack of voice to influence their profession. However, most KY nurses also expressed commitment to their occupation along with a desire to assume the role of leaders who can directly influence their own workplace transformation. This study adds to the national literature by outlining perceived contributors to the nursing shortage and providing recommendations directly from nurses regarding measures to effectively recruit and retain the most vital members of healthcare’s largest profession in the aftermath of a pandemic.

Key Words: nursing workforce, nursing shortage, pandemic, empowered leaders, solutions, retention, distress

Ninety percent of nursing associations from across the globe have reported concerns about the numbers of nurses who have left the nursing profession, or are planning to leave...Ninety percent of nursing associations from across the globe have reported concerns about the numbers of nurses who have left the nursing profession, or are planning to leave in the wake of COVID-19 pandemic due to workloads, stress, and burnout (ANF, 2022b; Chan et al., 2021; Dimino et al., 2021; International Council of Nurses, 2021). The American Nurses Association (ANA) conducted a series of National Impact Assessments (NIA) over three years to measure the ongoing impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the nursing workforce and to inform decision making efforts to support nurses during this critical time (ANA, 2021; 2023, ANF, 2022). Persistent concerns expressed by nurses included physical and psychological well-being, extended work hours, workplace safety, work-related incivility, understaffing, and perceived lack of support (ANF, 2022; Butler et al., 2021; Dimino et al., 2021). To maintain nurses’ safety, health, and well-being, healthcare institutions need to acknowledge sources of stress and implement organizational interventions that empower nurses to guide their own workplace transformation (Arnetz et al., 2020; Thomas, et al., 2016; World Health Organization, 2020).

(Data Source: COVID-19 National Impact Assessment, ANA, 2021; ANA, 2023; ANF, 2022)

Filtering of the ANA national data by state illustrated that negative experiences from the pandemic were reported even more frequently by Kentucky (KY) nurses (ANA, 2021; 2023, ANF, 2022). However, a follow up study revealed that KY nurses remained committed to their profession, but longed for a voice that would allow them to influence patient care and decisively speak to matters relating to professional nursing practice.

There is no better time than during the aftermath of a pandemic to empower all nurses as influential decision makers, in every healthcare setting, and across all corners of nursing practice...There is no better time than during the aftermath of a pandemic to empower all nurses as influential decision makers, in every healthcare setting, and across all corners of nursing practice so they can actively lead their own workplace transformation. This article describes a study that adds to the national literature by providing recommendations directly from nurses who have outlined measures to effectively retain and recruit members of healthcare’s largest profession.

Impact of COVID-19 on the Nursing Workforce

NIA Findings for the United States (Year 2)

Data obtained from the NIA Year Two pulse survey were examined describing perceptions of United States (U.S.) nurses (n = 11,964) during the second year of the pandemic (ANF, 2022). More than half (52%) of national NIA respondents from all employment settings reported they were considering or planning to leave their nursing position within the next six months (ANF, 2022). Respondents described experiences of increased bullying (66%) and violence (33%), most commonly from patients and families (76% and 69% respectively in the acute care setting). More than half (51%-71%) of these nurses felt stressed, frustrated, exhausted, overwhelmed, overworked, and anxious while 19% reported feeling betrayed and hopeless (25% and 24% respectively in acute care). Only 9% of national respondents felt empowered to change their situation (ANF, 2022).

Only 9% of national respondents felt empowered to change their situation.More than half (54%) of the nurses ranked the severity of their staffing shortage as “serious” and more than half (52%) also indicated they were considering/planning to leave their position. Reasons for leaving were primarily related to “negative effects of work on health/well-being” (51%) and “insufficient staffing” (55%). The NIA also evaluated workplace support using measures ranging from 1 to 5 on a Likert scale, with 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The results of this measurement pointed to yet another important source of distress: U.S. nurses were neutral or disagreed that their organization would notice the best job possible (2.7), cared about their well-being (2.8), responded to complaints (2.7), took pride in their accomplishments (2.8), or valued their contributions (2.9).

NIA Findings for the United States

NIA Findings for the US (Year 3)

Thought leaders, and policymakers are urged to collaboratively address current and long-standing workforce problems with nurses in a post-COVID world.During the third and final year of the NIA, most (64%) of acute care nurse respondents (n = 1,023) reported escalation of verbal abuse directed toward nurses, with almost half (47%) answering no/unsure to having a structure in place to report this abuse and more than half (55%) indicating that they were considering/planning to leave their position in the next 6 months. These findings are even more concerning given the robust national efforts currently underway to recruit and retain the next generation of nurses during the height of a persistent critical nursing shortage (Hollowell, 2023). Thought leaders, and policymakers are urged to collaboratively address current and long-standing workforce problems with nurses in a post-COVID world (Buerhaus, 2021).

Nurses from all employment settings across KY reported findings similar to the national trends from the NIA...but often at greater frequencies.NIA Findings for Kentucky

The national NIA data were filtered to allow for a comparative analysis of nurses residing or working in Kentucky during the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic (ANF, 2022). Nurses from all employment settings across KY reported findings similar to the national trends from the NIA (e.g. stressed, frustrated, exhausted), but often at greater frequencies. Table 1 shows this comparison using select assessment descriptors from a sample of all U.S. nurses (n = 11,964), compared to the NIA sample of all KY nurses (n = 104), and followed by acute care nurses (n = 65) in Kentucky (ANF, 2022).

Table 1. Comparison of Select Assessment Descriptors: Findings from the Second Year NIA

|

ASSESSMENT DESCRIPTORS |

ALL US |

ALL KY |

KY ACUTE CARE |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Stressed |

71% |

77% |

82%* |

|

Frustrated |

69% |

68% |

72% |

|

Exhausted |

65% |

72% |

83%* |

|

Overwhelmed |

58% |

65% |

72%* |

|

Overworked |

51% |

55% |

65%* |

|

Anxious |

51% |

55% |

60% |

|

Burnout |

49% |

50% |

63%* |

|

Unsupported |

42% |

43% |

52%* |

|

Sad |

36% |

39% |

49%* |

|

Depressed |

31% |

31% |

38% |

|

Hopeless |

19% |

17% |

26% |

|

Worthless |

10% |

17% |

25%* |

|

Empowered |

9% |

8% |

5% |

1 KY nurse rankings exceeding the national average are bold/italicized

2 KY acute care nurse rankings that are ≥ 10% higher than the national average are also noted with an asterisk

(ANF, 2022)

Findings were even more concerning among Kentucky acute care nurse respondents when compared to the national trend for acute care nurses.Findings were even more concerning among Kentucky acute care nurse respondents when compared to the national trend for acute care nurses. In KY, 26% of respondents reported feelings of hopelessness and 25% reported feelings of worthlessness (compared to 19% and 10% respectively for all U.S. nurses). Corresponding with these alarming findings, nurses from all NIA groups reported very low scores for the descriptor empowered; only 9% of all U.S. nurses compared to an even lower 5% among acute care nurses in Kentucky who felt empowered (ANF, 2022) (see Table 1).

Kentucky Nurse Leaders Respond

The NIA results filtered by the state of KY (as described above) prompted leaders of the Kentucky Nurses Association (KNA) in collaboration with the Kentucky Organization of Nurse Leaders (KONL) to urgently respond and further explore the experiences of distressed nurses in KY during the COVID-19 pandemic. Distress was defined as “pain or suffering affecting the body or the mind” (Merriam-Webster, 2022, para 1). A survey instrument was developed and launched by KNA researchers to carefully examine the employment intentions and perceptions of distressed Kentucky nurses regarding work, safety, emotional health, physical health, and professional stability while confronting the challenges of the pandemic.

The purpose of this study was to collect and analyze original data from nurses residing or working in the state of KY at the time of a significant nursing shortage during the COVID-19 pandemic. The NIA national database served as the source for comparisons with the actual experiences of nurses in one state (KY). However, narrative insights resulting from this study could reveal new insights for understanding the story behind U.S. trends, thus informing the design of national strategies to effectively retain nurses who are some of the most vital members of healthcare’s largest profession.

Study Methods

Instrument Development

Survey questions and response options were developed by one of the authors, a PhD prepared nurse researcher. The survey content was informed by a review of current nursing literature (ANA, 2021; ANF, 2022; Butler et al., 2021; Dimino et al., 2021; Godsey, 2021; Zauche et al., 2022) and with guidance from leading nurse experts affiliated with the KNA. Survey items were vetted by nurse leaders from practice, education, leadership, research, and professional organizations throughout Kentucky.The KNA and KONL distributed the survey to a population of 89,000 Kentucky nurses requesting participation in the study.

Survey participants were asked to: a) rate (Likert scale, 1= strongly disagree to 5= strongly agree) and then rank (pick 3) possible contributors to the nursing shortage in Kentucky from a list of 22 options; b) rate possible supportive actions to alleviate the nursing shortage (professional, personal, social/community); and c) rate how likely they were to leave their current job or the nursing profession within the next three months. Open ended questions in portions of the survey gave participants the opportunity to voluntarily explain their answers for the three items above, as well as to: 1) describe three things which would best support them as a nurse right now, and 2) describe what could be done to improve the image of nursing.

Participants identifying as a KY nurse of any gender between the ages of 20-65+ were included in this analysis.Ethical Considerations

Approval was obtained from a state university institutional review board to conduct a retrospective analysis of anonymous survey data which recorded nurse perceptions of the potential causes of, and responses to, the nursing shortage in KY during the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants identifying as a KY nurse of any gender between the ages of 20-65+ were included in this analysis. Participants who did not identify as KY nurses were automatically exited from the survey. Data cleaning was achieved by removing incomplete responses and responses that were the same for every question (e.g., answering all 5s or all 1s, or copy/pasting repeated messages in all/most text boxes), suggesting possible response set bias.

Data Analysis

The anonymous KNA survey instrument was administered electronically over two weeks during Fall 2021 using Survey Monkey©. The survey was accessible through KNA and KONL organizational digital media and communication platforms. From a state-wide population of 89,000 nurses, 1246 individuals accessed the survey, with 850 qualified complete responses analyzed. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze anonymous quantitative data (frequencies and measures of central tendency). Voluntary open ended narrative responses (taken from specific text box comments) were coded by type of response and analyzed for common themes.

Results

Participant Demographics

Sixty-four percent of participants were between the ages of 45-64. There were 91% female respondents; 61% had 21-30+ years of experience, and 69% were prepared at the undergraduate level (33% associate degree and 36% bachelor’s degree). Participants’ current work settings included 46% hospital/acute care and 25% outpatient clinic and school nursing; 7% were unemployed.

Perceived Contributors to the Nursing Shortage

...many of the top-rated concerns related to a lack of support and a lack of voice to influence their profession.While some of the highest rated contributors (4.0-4.7 of a possible 5.0) to the nursing shortage concerned insufficient staffing/exhaustion, and pay, many of the top-rated concerns related to a lack of support and a lack of voice to influence their profession. A complete list of perceived contributors to the nursing shortage as reported by Kentucky nurses (n = 850) is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Perceived Contributors to the Nursing Shortage

|

Perceived Contributors to the Nursing Shortage in Kentucky (n = 850) |

|

|---|---|

|

Answer Choices |

Average |

|

Lack of sufficient nursing staff /heavy patient loads |

4.7 |

|

Physical exhaustion |

4.5 |

|

Lack of support staff to alleviate non-nursing tasks |

4.5 |

|

Lack of time to get away for meal/breaks from work |

4.4 |

|

Not enough pay |

4.3 |

|

Lack of support for nurses from management/administration |

4.3 |

|

Lack of voice to influence issues that directly impact nursing |

4.2 |

|

Lack of voice to influence issues that directly impact patient care |

4.2 |

|

Lack of public support for nurses/healthcare workers |

4.0 |

|

Feelings of hopelessness/helplessness that things will get better |

3.9 |

|

Anxiety/depression |

3.9 |

|

Verbal abuse from patients and/or their family members |

3.9 |

|

Moral distress due to death/disability of patients/public |

3.9 |

|

Fear of transmitting COVID to family/friends due to working as a nurse |

3.8 |

|

Lack of on-site/on-demand mental/emotional/spiritual support services |

3.7 |

|

Lack of resources/training on how to manage stress/anxiety |

3.6 |

|

Lack of resources/training on how to manage conflict with patients/family |

3.6 |

|

Moral distress due to death/disability of staff |

3.6 |

|

Fear of getting COVID due to work as a nurse |

3.4 |

|

Lack of childcare |

3.4 |

|

Physical abuse from patients and/or their family members |

3.4 |

|

Lack of needed resources to ensure employee safety (PPE) |

3.3 |

Nurses (n = 850) were also asked to rank (i.e., select the top 3) from the same list of contributors to the nursing shortage. Most of the highly ranked contributors (e.g., heavy patient loads, not enough pay, physical exhaustion) were comparable to the highly rated contributors described in the previous t able, further validating this finding. The most highly ranked contributors to the nursing shortage are listed in Table 3 in descending order (73% - 10%).

Table 3. List of Perceived Contributors to the KY Nursing Shortage by Rank (in Descending Order)

|

Answer Choices |

Average |

Responses |

|---|---|---|

|

1. Lack of sufficient nursing staff /heavy patient loads |

73% |

617 |

|

2. Not enough pay |

41% |

346 |

|

3. Physical exhaustion |

26% |

218 |

|

4. Fear of transmitting COVID to family/friends due to working as a nurse |

24% |

203 |

|

5. Lack of support staff to alleviate non-nursing tasks |

22% |

190 |

|

6. Lack of support for nurses from management/administration |

22% |

189 |

|

7. Fear of getting COVID due to work as a nurse |

17% |

144 |

|

8. Feelings of hopelessness/helplessness that things will get better |

12% |

98 |

|

9. Lack of support for nurses/healthcare workers |

10% |

86 |

Actions to Alleviate the Nursing Shortage

Kentucky nurses rated (Likert scale, 1-5) numerous actions that could be employed to alleviate the nursing shortage in the aftermath of the pandemic. Many of the highest rated supportive actions logically corresponded to the perceived underlying causes (i.e., contributors) of the nursing shortage described previously in Tables 2 and 3. Corresponding actions to alleviate the nursing shortage included better staffing, higher pay, and professional voice (or the ability to influence decisions).

Corresponding actions to alleviate the nursing shortage included better staffing, higher pay, and professional voice.This list of highest rated actions was further divided by financial and non-financial forms of support. Financially supportive actions to alleviate the nursing shortage (indicated by dollar signs) included more staff to alleviate heavy patient assignments, higher pay, non-clinical staff to offload non-essential nursing tasks, financial incentives, and student loan forgiveness. Non-financial supportive actions included breaks from work, ability to influence decisions impacting nursing, ability to influence decisions impacting patient care, better communication between nursing and management/administration, and solutions to address physical/verbal abuse from patients/family members. See Table 4 for highest rated actions to alleviate the nursing shortage, in descending order (4.8 - 4.2).

Table 4. Actions to Alleviate the Nursing Shortage in KY

|

Financial Implication |

Actions to Support Nurses |

Rating |

|---|---|---|

|

$ |

More nursing staff to alleviate heavy patient assignments |

4.8 |

|

$ |

Higher pay |

4.6 |

|

Adequate time away for lunch/work breaks |

4.5 |

|

|

$ |

More non-clinical staff to offload non-essential nursing tasks |

4.5 |

|

Ability to influence decisions that directly impact nurses |

4.4 |

|

|

Ability to influence decisions that directly impact patient care |

4.4 |

|

|

$ |

Financial incentives/profit sharing |

4.4 |

|

Better communication pathways between nursing staff and management/administration |

4.3 |

|

|

$ |

Student loan forgiveness |

4.3 |

|

Consistent availability of PPE |

4.2 |

|

|

Implement effective solutions at work to address physical/verbal abuse from patients/family members |

4.2 |

Employment Intentions

When asked about employment intentions, 25% of participants indicated they were likely/extremely likely to leave their current job as a nurse within the next three months, while 16% reported they were likely/extremely likely to leave their primary occupation of nursing. Optional narrative comments (n = 339) revealed primary reasons for potentially leaving their job as a nurse, and what could be done to better support them. These findings are described in the paragraphs that follow.

Narrative Response Analyses and Emerging Themes: Plan to Stay or Leave Nursing

Content analysis of 339 narrative responses from Kentucky nurses regarding employment intentions were collapsed into two broad categories: 1) Plan to Stay in Nursing and 2) Plan to Leave Nursing. Fifteen themes were identified within these categories to explain why participants planned to stay or leave their current job as a nurse.

Plan to Stay in Nursing. The Plan to Stay in Nursing category clearly emerged as the most common theme. There were 117 mentions that related to enjoyment/fulfilment in their work as a nurse. In this category, those who planned to stay in nursing indicated they were waiting for retirement or had made a long-term commitment to their nursing career (28 mentions).

Plan to Leave Nursing. The second category of responses was Plan to Leave Nursing with participants indicating an intention to leave the nursing profession within the next three months. Reasons that emerged from this category (followed by the number of mentions) included: Stressed/burned out/exhausted (n = 28); need for higher pay/benefits (n = 23); considering leaving the profession/looking for other opportunities (n = 19); retirement/end of career (n = 16); and not appreciated/respected (n = 9) (see Table 5). It is significant to note the most frequently cited reasons that nurses gave for possibly leaving their profession related to 1) heavy patient assignments/exhaustion, and 2) insufficient pay. These reasons were also selected among the top rated and ranked perceived contributors to the nursing shortage noted from the quantitative data portions of the survey, even further validating these findings (refer to Tables 2 and 3).

Table 5. Plan to Stay or Leave Nursing in KY

|

Themes |

Number of Mentions (n = 299) |

|---|---|

|

Plan to Stay in Nursing |

|

|

Enjoy being a nurse |

117 |

|

Waiting for retirement |

14 |

|

Invested too many years, cost, or work on career |

14 |

|

Leaving/left bedside nursing, not the profession |

11 |

|

Other |

22 |

|

Plan to Leave Nursing |

|

|

Stressed/burned out/exhausted |

28 |

|

Higher pay/salary/benefits |

23 |

|

Considering leaving the profession/other opportunities |

19 |

|

Retirement/end of career |

16 |

|

Not appreciated/respected |

9 |

|

Vaccine mandate |

5 |

|

Concerned for safety |

4 |

|

Other |

12 |

Measures to Support Nurses

The most common non-financial reasons were to ensure nurses feel valued, respected, and supported by management...Kentucky nurses were generous with suggestions regarding measures to support nurses and provided 741 optional responses. Two distinct categories, non-financial and financial reasons, and 11 thematic descriptions emerged through content analysis of a random selection of 200 responses describing workplace measures that could best support nurses. The most common non-financial reasons were to ensure nurses feel valued, respected, and supported by management (24 mentions). The highest number of mentions for financial reasons included more nursing staff/improved staffing ratios (n = 68) and higher pay/financial incentive/retention bonus/benefits respectively (n = 59) (see Table 6).

Table 6. Workplace Measures to Best Support Work as a Nurse in KY

|

Financial Implication |

Themes |

Number of Mentions |

|---|---|---|

|

$ |

More nursing staff/improved staffing ratios |

68 |

|

$ |

Higher pay/financial incentive/retention bonus/benefits |

59 |

|

Ensure nurses feel valued, respected, and supported by management |

24 |

|

|

Mandate vaccine and require masks |

14 |

|

|

Mental health/crisis support/stress management |

8 |

|

|

Provide appropriate PPE and supplies |

7 |

|

|

$ |

More ancillary staff |

6 |

|

$ |

Student loan forgiveness |

5 |

|

Ensure nurses get breaks and time off the unit |

4 |

|

|

Increase public awareness of the work of nurses and of the pandemic |

4 |

|

|

$ |

Provide childcare |

2 |

*A single respondent’s comments may apply to more than one theme.

Discussion

This study was conducted to further examine findings from the ANA NIA pulse surveys that described nurses’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Results from the first two-years of the study (ANA, 2021; ANF, 2022) revealed many concerning trends, suggesting that the lingering pandemic was impacting U.S. nurses negatively and resulting in significant distress to the nursing profession as a whole. Filtering of the ANA national level data (n = 11,964) by state illuminated the finding that negative experiences resulting from the pandemic were being reported even more frequently by KY nurses (n = 104) than was observed in national trends (ANA, 2021; ANF, 2022).

Results from the first two-years of the study revealed many concerning trends, suggesting that the lingering pandemic was impacting U.S. nurses negatively...To further explore the feelings and perceptions of distressed nurses, the KNA promptly responded by surveying a much larger sample of KY nurses (n = 850) to determine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the state’s nursing workforce. The sample was rich in experience, with most (61%) possessing 21-30 years of nursing experience. Almost a quarter of the sample indicated that it was likely they would leave their current position in the next three months.

The highest rated perceived contributors to the nursing shortage reported by KY nurses in the KNA study were consistent with most of national findings, which frequently involved pay and the persistent lack of nursing and support staff. Only 8% of KY nurses felt empowered to change their situation; however, they clearly expressed a desire to be empowered as leaders, i.e., to have a voice that would allow them to influence the nursing profession and patient care.

Although KY nurses reported distressful situations, they were not deterred.Although KY nurses reported distressful situations, they were not deterred. While numerous issues for the workforce were identified, most respondents indicated a plan to stay and reaffirmed their commitment to the nursing profession and the KY communities they served. The majority of respondents reported that they enjoyed being a nurse and were fulfilled by the work they do and the significant contributions they make to healthcare in KY.

Limitations

...concerned employers are encouraged to share and compare the findings reported by nurses in this study with actual practices, resources, and overall support...Findings from this follow up study in KY were largely consistent with national data, but with even more concerning findings among KY nurses working in acute care settings. However, data collection was limited to nurses who worked or resided in KY which limits generalizability of some findings. Therefore, benefit could be derived by using this study as a model to examine individual state level data on a larger scale. Additionally, all data were reported from the perspective of nurses and did not include actual determinations of the availability or absence of financial or non-financial resources at any employing institution. However, concerned employers are encouraged to share and compare the findings reported by nurses in this study with actual practices, resources, and overall support currently provided by the institution to determine if opportunities for quality improvement, enhanced staff communication, and empowerment of the nursing workforce exist and are sufficient.

Implications for Nursing

A national trend of concern pointed to a nursing workforce under tremendous stress, with more than half of nurse respondents reporting frustration, stress, exhaustion, feeling overwhelmed and/or overworked, anxiety, and burnout. Many also indicated that they were victims of bullying or violence from patients/families or co-workers. More than a third of national respondents reported feeling sad and depressed, while 25% of Kentucky respondents who worked in acute care reported feeling hopeless and worthless. Kentucky nurses reported stress (77%) and exhaustion (72%) more frequently than the national average, with acute care nurses in Kentucky reporting a lack of empowerment (5%) to improve their situation. Nurses who participated in the ANA national study were neutral or disagreed (2.7 - 2.9) that their organization would notice the best job possible, took pride in their accomplishments, or valued their contributions.

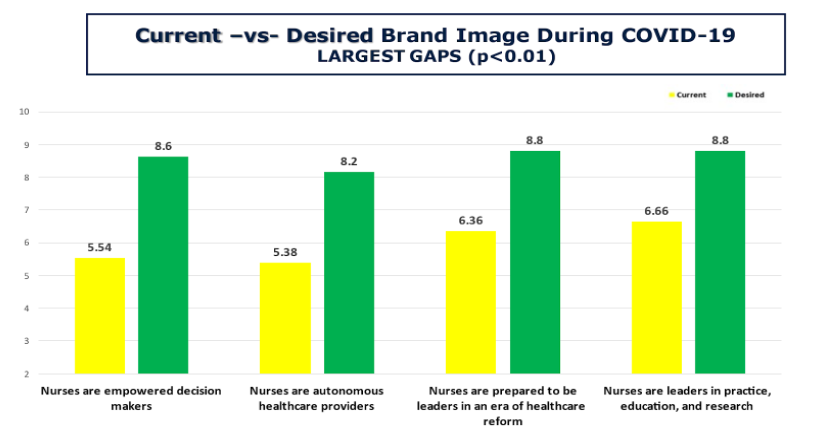

It is worth noting that a separate quantitative study, also conducted with a sample of KY nurses, explored nurses’ perceptions of the brand image of nursing during the COVID-19 pandemic (Godsey et al., 2022). The concept “brand image of nursing” refers to all the thoughts, associations, beliefs, feelings, ideas, emotions, and impressions held by nursing and the public (e.g., good and bad) about the profession of nursing (Godsey & Hayes, 2022). Significant gaps were found which further emphasized how Kentucky nurses (n =126) saw their profession’s current brand image during the pandemic compared to the image they most desire (p = 0.01). Largest gaps between current versus desired image concerned the roles nurses as leaders, empowered decision makers, and autonomous healthcare providers (see Figure 1). Findings will be described in another paper but offer strategies for the profession of nursing when exploring the potential impact that “All Nurses Are Leaders” (Godsey & Hayes, 2023) could exert on the ability for nurses to proactively address workforce issues that influence their decision to stay, leave, or advance in their profession.

Figure 1. Largest Gaps Between KY RNs Current -vs- Desired Image During COVID (n=126)

Printed with permission: Godsey, J.A., White, D. & Hayes, T. (2022).

Strategies should be considered which proactively address nurses’ intentions to leave their current position or the nursing profession through targeted shared governance and advocacy efforts...The NIA studies referenced above could inform an urgent call to action for nurse-led interventions designed to maintain the health, safety, and well-being of the nursing workforce. Such actions should be an ongoing focus of healthcare institutions, with direct collaboration from frontline nurses for the most effective workplace adaptations to occur (Arnetz et al., 2020). Strategies should be considered which proactively address nurses’ intentions to leave their current position or the nursing profession through targeted shared governance and advocacy efforts designed to support the retention of nurses and maximize a healthy workplace environment.

In the wake of a persistent pandemic, nurses have been appropriately offered training and generous resources to decrease stress and improve their resiliency. While addressing resiliency among nurses is one critically important step in resolving distress related to attrition, for meaningful progress toward reversing the nursing shortage, the underlying, systemic, root causes of the problem must also be addressed in a manner that engages the collective voice of nurses, as influential leaders, and decision makers. Findings from both the NIA and the KNA follow up study of KY nurses reinforce the urgent need to simultaneously address causes of distress among nurses that are likely contributing to the nursing shortage.

...for meaningful progress toward reversing the nursing shortage, the underlying, systemic, root causes of the problem must also be addressed in a manner that engages the collective voice of nurses...Opportunities identified by nurses included: Actively preventing exhaustion by ensuring sufficient support staff and enforcing sufficient time away from work for meals/breaks/time off; enhancing communication through direct nursing staff engagement and increasing visible acts of support from management/administration/employers (White & Godsey, 2022). Significant opportunity exists to maximize the brand position and influence of all nurses as empowered leaders who can leverage their essential professional roles to improve the quality of patient care while acting as agents of change to transform their own profession (Godsey, Houghton et al., 2020; Godsey, Perrott et al., 2020; Joseph et al., 2023).

Nurses in this study felt that actions to alleviate the nursing shortage should include better staffing, higher pay, and professional voice (i.e., the ability to influence decisions with patients and in their profession). These findings could inform meaningful dialogue with all nurses from the bedside to the boardroom and serve as a springboard to the collective design of actions with nurses that address persistent financial concerns (e.g., the creation of innovative reimbursement models). Such actions might also reduce/eliminate the non-financial modifiable contributors to the nursing shortage identified by respondents in this study (e.g., breaks from work, voice to influence change, and better support/communication with management [see Table 4]).

Some solutions to the nursing shortage identified by study participants seem quite simple and obvious yet have remained elusive within the nursing profession.It is worth emphasizing that NIA respondents from all settings reported the experience of increased bullying (66%) and violence (33%) that most commonly occurred from patients and their families (76% and 69% respectively in the acute care setting). Some solutions to the nursing shortage identified by study participants seem quite simple and obvious yet have remained elusive within the nursing profession. These include zero tolerance policies to decisively address bullying and violence from patients/families, as nurses do have a much higher risk of workplace violence compared to most other professions (BLS, 2021). Also important is the elimination of unacceptable working conditions, such as exhaustion resulting from frequently skipped meals and the persistent lack of breaks.

The concept of “nurse as leader” has too frequently been limited to a hierarchical structure of managers and executives...More than half of the national respondents (51%-71%) felt stressed, frustrated, exhausted, overwhelmed, overworked, and anxious while 19% reported feeling betrayed and hopeless (22% and 23% respectively in acute care). Only 9% of national respondents felt empowered to change their situation (ANF, 2022). The concept of “nurse as leader” has too frequently been limited to a hierarchical structure of managers and executives, rather than the collective contributions of a highly qualified group of autonomous, licensed, healthcare professionals (Huber & Joseph, 2021; Williams et al., 2016). The ANA outlines the urgent need for academic leaders, regulators, policymakers, and healthcare systems to produce collaborative solutions that meaningfully address challenges for the nursing workforce (ANA, 2022; ANA on the Frontline, 2023; Thomas et al., 2016).

Conclusion

This study adds to the national literature by providing recommendations directly from nurses who have outlined measures to effectively recruit and retain members of healthcare’s largest profession. Even in the midst of a devastating pandemic, more than 1,000 KY nurses took the time to respond and let the nation know that while they were distressed, they had not lost their purpose: To protect, promote, and optimize health; prevent illness and injury; facilitate healing; alleviate suffering; and advocate for the care of individuals, families, groups, communities, and populations (ANA, 2015). Most KY nurses were steadfastly committed to their profession yet clearly longed for a voice that would allow them to meaningfully influence patient care and decisively speak to matters relating to their professional practice as licensed autonomous professionals.

Even in the midst of a devastating pandemic, more than 1,000 KY nurses took the time to respond and let the nation know that while they were distressed, they had not lost their purpose...The brand position that All Nurses Are Leaders can certainly be achieved, but it will take a unified approach to make it a reality (Godsey & Hayes, 2023; Joseph, et al., 2023). As we move past the persistent grasp of the COVID-19 pandemic, the nursing profession is uniquely positioned to embrace the contributions of all nurses who possess the academic qualifications, legal licensure, clinical competencies and professional brand identity to boldly use their voices as leaders capable of influencing healthcare and elevating contemporary nursing practice, if given the opportunity (Godsey & Hayes, 2023; van der Cingel, et al., 2020). Again, the optimal time is now, during the aftermath of a pandemic, to hear what nurses are saying and empower them as influential decision makers to lead their own workplace transformation (Arnetz et al., 2020; Finkelman & Kenner, 2013; Godsey, Houghton, et al., 2020; Godsey et al., 2022; Joseph et al., 2023; World Health Organization, 2020). The quotes below illustrate this from a regional to a global perspective:

Nurses must be portrayed as leaders and not handmaidens to doctors and the healthcare system. Empower nurses to have greater impact on the decisions that affect healthcare delivery and how they perform their respective job. (Causes of the nursing shortage: KNA Survey Respondent, 2022).

…. strong leadership will be required to realize the vision of a transformed health care system. Although the public is not used to viewing nurses as leaders, and not all nurses begin their career with thoughts of becoming a leader, all nurses must be leaders… (IOM, 2011, para 2).

Acknowledgments: There are no conflicts of interest to disclose. This research received no funding. The authors gratefully acknowledge the support and guidance of the Kentucky Nurses Association, in collaboration with KONL, which made this research possible.

Authors

Dolores White, DNP, RN, CNE

Email: White21@nku.edu

Dolores White is the President of the Kentucky Nurses Association and is an Assistant Professor at Northern Kentucky University in the Graduate Nursing Program. She has 28 years of nursing experience in a variety of clinical, education, and leadership roles that have provided her with the opportunity to advocate for nurses and the nursing profession at the local, state, and federal level.

Judi Allyn Godsey, PhD, MSN, RN

Email: Judi.godsey1@gmail.com

ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8258-8404

Judi Godsey is faculty in the DNP program at the University of Kentucky College of Nursing as well as Director for the Institute for the Brand Image of Nursing (IBIN). Her 32 years of nursing experience include a progressive program of research and nursing advocacy at the state and national level. Dr. Godsey has co-authored multiple publications which highlight original research findings on the ”Brand Image of Nursing” and describe significant gaps between nurses’ current versus desired image. Recommendations arising from this seminal work are for nurses to live the brand image "All Nurses Are Leaders" across all corners of nursing and throughout the public domain.

References

American Nurses Association. (2021). Pulse on the nation’s nurses COVID-19 survey series: Mental health and Wellness #2. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/work-environment/health-safety/disaster-preparedness/coronavirus/what-you-need-to-know/mental-health-and-wellness-survey-2/

American Nurses Association. (2022). COVID-19 impact assessment survey – the second year. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/work-environment/health-safety/disaster-preparedness/coronavirus/what-you-need-to-know/covid-19-impact-assessment-survey---the-second-year/

American Nurses Association. (2023). Pulse on the nation’s national survey series results. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/work-environment/health-safety/disaster-preparedness/coronavirus/what-you-need-to-know/survey-series-results/

American Nurses Foundation. (2022). Pulse on the nation’s nurses survey series: COVID-19 two-year impact assessment survey. https://www.nursingworld.org/~4a2260/contentassets/872ebb13c63f44f6b11a1bd0c74907c9/covid-19-two-year-impact-assessment-written-report-final.pdf

American Nurses Foundation. (2023). Three-year annual assessment survey: Nurses need increased support from their employer. https://www.nursingworld.org/~48fb88/contentassets/23d4f79cea6b4f67ae24714de11783e9/anf-impact-assessment-third-year_v5.pdf

ANA on the Frontline. (2023). Thousands of RNs plan to leave the profession by 2027. American Nurse Journal, 18(6), 32.

Arnetz, J., Goetz, C., Arnetz, B., & Arble, E. (2020). Nurse reports of stressful situations during the COVID-19 pandemic: Qualitative analysis of survey responses. International Journal of Environments Research and Public Health, 17, 8126. http://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17218126

Buerhaus, P. I. (2021). Current nursing shortages could have long-lasting consequences: Time to change our present course. Nursing Economic$, 39(5), 247-250.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2021). Incidence rates for nonfatal assaults and violent acts by industry, 2020. U.S. Department of Labor. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/WPVHC/Nurses/Course/Slide/Unit1_6

Butler, R. J., Lai, G., & Wilson, B. L. (2021, May/June). Nurses’ wages and hours of work in the COVID-19 era. Nursing Economic$, 39(3), 132-138.

Chan, G. K., Bitton, J. R., Allgeyer, R. L., Elliot, D., Hudson, L. R., & Moulton Burnwell, P. (2021, May 31). The impact of COVID-19 on the nursing workforce: A national overview. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 26(2). https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol26No02MAN02

Dimino, K., Learmonth, A. E., & Fajardo, C. C. (2021, October). Nurse managers leading the way: Reenvisioning stress to maintain healthy work environments. Critical Care Nurse, 41(5), 52-58. https://doi.org/10.4037/ccn2021463

Finkelman, A., & Kenner, C. (2013). The image of nursing: What it is and how it needs to change. In Professional Nursing Concepts (2nd ed., pp. 85-97). Jones & Bartlett.

Godsey, J. A. (2021). Outcomes report from the COVID-19 survey of Kentucky nurses. https://s3.amazonaws.com/nursing-network/production/files/105994/original/KNA_COVID_Survey_Report_Final_v2_10-21-21.pdf?1634914144

Godsey, J. A., & Hayes, T. (2022). IBIN: Definition of the brand. Institute for the brand image of nursing. https://www.brandimageofnursing.com/ibin

Godsey, J. A., & Hayes, T. (2023). All nurses are leaders: 5 steps to reconstruct the professional identity and brand image of nursing. Nurse Leader: Special Edition (online early edition), January, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mnl.2022.12.012

Godsey, J. A., Houghton, D. M., & Hayes, T. (2020). Registered nurse perceptions of factors contributing to the inconsistent brand image of the nursing profession. Nursing Outlook, 68(6), 808–821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2020.06.005

Godsey, J. A., Perrott, B., & Hayes T. (2020). Can brand theory help re-position the brand image of nursing? Journal of Nursing Management,28(4), 968–975. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13003

Godsey, J. A., White, D., & Hayes, T. (2022). Brand image of nursing before and during a pandemic: Perceptions of Kentucky nurses compared to national trends (10/21/2022). Innovation Across Kentucky: Virtual Live Stream Event. Kentucky Organization of Nurse Leaders (KONL) Spring Conference (Keynote).

Hollowell, A. (2023). Nurses feel unprepared for future pandemics, unsupported by employers, survey finds. Becker’s Hospital Review, 1/26/23. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/nursing/nurses-feel-unprepared-for-future-pandemics-unsupported-by-employers-survey-finds.html

Huber, D., & Joseph, M. L. (2021). Leadership and nursing care management (7th ed). Elsevier: Saunders.

Institute of Medicine. (2011). Future of nursing: Leading change, advancing health. National Academies Press.

International Council of Nurses. (2021). International Council of Nurses policy brief: The global nursing shortage and nurse retention. https://www.icn.ch/node/1297

Joseph, M. L, Godsey, J. A., Hayes, T., Bagomolny, J., Beandry, S., Biangone, M., Ernst, P., Godfrey, N., Lose, D., Martin, E., Ollerman, S., Siek, T., Thompson, J., & Valiga, T. (2023). A framework for transforming the professional identity and brand image of nurses as leaders (a paper created jointly by the International Society for the Professional Identity of Nursing (ISPIN) and the Institute for the Brand Image of Nursing (IBIN). In press, Nursing Outlook, 8/2023).

Merriam-Webster. (2022). Distress. Merriam-Webster.com. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/distress

Thomas, T. W., Seifert, P. C., & Joyner, J. C. (2016). Registered Nurses leading innovative changes. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing (21)3. https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol21No03Man03

van der Cingel, M., & Brouwer, J. (2021). What makes a nurse today? A debate on the nursing professional identity and its need for change. Nursing philosophy: An international journal for healthcare professionals, 22(2), [e12343]. https://doi.org/10.1111/nup.12343

White, D., & Godsey, J. (2022). Impact of a pandemic on nurse intention to stay or leave nursing. Sigma’s Creating Healthy Work Environments Conference, ID #: 112574, March 24-26, Washington DC.

Williams, T. E., Baker, K., Evans, L., Lucatorto, M. A., Moss, E., O’Sullivan, A., Seifert, P. C., Siek, T., Thomas, T. W., & Zittel, B. (2016). Registered Nurses as professionals, advocates, innovators, and collaborative leaders: Executive summary, Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 21(3). https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol21No03Man05

World Health Organization. (2020). Nursing and Midwifery. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/nursing-and-midwifery

Zauche, L. H., Pomeroy, M., Demeke, H. B., Mettee Zarecki, S. L., Williams, J. L., Newsome, K., Hill, & L., Dooyema, C.A. (2022). Answering the call: The response of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s federal public health nursing workforce to the COVID-19 pandemic. American Journal of Public Health, 112 (Sup53), S226-S230. https://www.doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2021.306703