Patient surges related to the COVID-19 pandemic, combined with the pre-existing and worsening nursing workforce shortage, have exacerbated the need to implement strategies that build a pathway to expand the current and future nursing workforce. Ideal strategies connect education and practice, based on supply and demand for healthcare professional skills. NursingNow, a global campaign that includes a USA initiative, declared the mission to elevate nurses and has called for them to be agents of change by leading innovative solutions to existing problems. This article highlights two such nurse-led innovation exemplars that fostered the connection of education and practice to engage interprofessional students. We describe the development and implementation of these initiatives and accomplishments achieved. The discussion reviews issues around contracts, compliance, and accreditation; incentives for partnerships; and the development of a health professional student corps. The call to action invites nurses, as the largest healthcare workforce, to consider leadership roles in efforts to incentivize centralized solutions and ongoing academic-practice partnerships.

Key Words: nurses, nursing shortage, academic-practice partnerships, interprofessional education, interprofessional practice, pandemic, workforce development, COVID-19, nurse leaders, policy, student services corps, healthcare volunteers, patient-centered care, population health, Nursing Now USA

...80% of healthcare leaders reported experiencing a workforce shortage...When the coronavirus pandemic of 2019 (COVID-19) came to the United States (U.S.) in early 2020, all aspects of healthcare were impacted. The virus led to more than 50 million infections and 800,000 deaths in the US by the end of 2021 and overwhelmed the healthcare system (AJMC, 2021), forcing systems to adapt to meet the needs of patients. In a 2021 survey of healthcare leaders in North Carolina (NC), 80% of respondents reported experiencing a workforce shortage at the time of the survey, with 52% claiming it was worse than before the pandemic (Jones et al., 2021).

...the two most common types of workers in short supply were registered nurses and nursing assistants...Both prior to and during the pandemic, the two most common types of workers in short supply were registered nurses (RNs) and nursing assistants (Jones et al., 2021). Despite these shortages, nurses, who make up the largest portion of the healthcare workforce, have been at the center of the pandemic relief efforts (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [NASEM], 2021a). RNs have contributed across the health continuum, from contact tracing within the community to caring for the sickest patients in intensive care units (American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 2020).

Not only have working nurses been affected by the pandemic, but the student educational pathways in nursing and other health professions have been disrupted. While this was a concern for many rural and underserved communities prior to the pandemic, this problem heightened to a critical level. Student clinical experiences, a necessity for credentials among health professions programs, were frequently cancelled due to low supply of personal protective equipment (PPE); lack of preceptors due to changing operating procedures; and social distancing protocols that limited the capacity of sites to include additional personnel (Jones et al., 2021; Redden, 2020). Throughout the pandemic, many elective cases were cancelled to prepare for potential patient surges, further reducing the number of healthcare workers who could serve as preceptors.

These changing methodologies resulted in fewer opportunities for exposure to and collaboration with other professions...As a result of these challenges, nursing and other health professions training programs were forced to use virtual clinicals or simulation experiences (Fogg et al., 2020). These changing methodologies resulted in fewer opportunities for exposure to and collaboration with other professions, raising concerns that learners will enter the workforce ill-prepared for both intra- and interprofessional practice (NASEM, 2021b). In a report about a study of the effects of COVID-19 on the healthcare workforce, a healthcare leader expressed concerns that, without these interprofessional interactions, students would return to “a more institutional model we have fought years to get away from” (Jones et al., 2021, p. 50). Returning to this previous model would risk losing decades of progress toward promoting interprofessional practice at the student level.

...interprofessional education and practice (IPEP) is vital to attain a workforce that is ready and able to care for local health needs through teamwork and collaboration.The World Health Organization (WHO) describes interprofessional practice (IPP) as “…multiple health workers from different professional backgrounds work[ing] together with patients, families, caregivers, and communities to deliver the highest quality of care” (WHO, 2010, p. 7). Interprofessional education (IPE) is the educational practice where those in two or more professions collaborate to “learn about, from, and with each other” (WHO, 2010, p. 7). IPE helps healthcare workers achieve IPP. The WHO deemed that interprofessional education and practice (IPEP) is vital to attain a workforce that is ready and able to care for local health needs through teamwork and collaboration (WHO, 2010).

Interprofessional teams are critical in the care of acute, chronic, and complex health and social support needs of COVID-19 patients (Michalec & Lamb, 2020). IPE and IPP are so essential to care that accreditation bodies have come together to provide guidance about how to embed these activities throughout all health professions programs (Health Professions Accreditors Collaborative, 2019). Nursing Now USA and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Future of Nursing: Campaign for Action also recognize the value of interprofessional teams. They have both called for nurses to promote equity by breaking down interprofessional barriers for the betterment of population health (Holloway et al., 2021; NASEM, 2021a). Furthermore, healthcare workers undergoing pandemic stressors are now reporting a stronger emphasis on cooperation and collaboration within and across healthcare professions (Langlois et al., 2020).

IPEP has the potential to improve patient outcomes and satisfaction, enhance workforce satisfaction, and reduce cost, all while expanding the current workforce and preparing the pipeline (Reeves et al., 2016). When delivered intentionally, IPEP has the potential to achieve the Quadruple Aim (i.e., improved quality, increased population health, reduced costs, and improved clinician experience), with teamwork playing a large part in the achievement of the fourth aim: addressing the needs of healthcare workers, and reducing stressors experienced by the past, current, and future healthcare workforce, including nurses (Bachynsky, 2020; Bodenheimer & Sinsky, 2014).

...surges of patients with COVID-19 have exacerbated the need to implement strategies to build a pathway to expand the current and future nursing workforce.Combined with the pre-existing and worsening nursing workforce shortage, surges of patients with COVID-19 have exacerbated the need to implement strategies to build a pathway to expand the current and future nursing workforce. Ideal strategies connect education (i.e., health professions students) and practice (i.e., current health professionals) to create academic-practice partnerships, based on the demand and supply for healthcare professional skills. With an emphasis on supply and demand of skills, these strategies can not succeed if executed in a professional silo; teamwork and collaboration are keys to efficiency, effectiveness, and resilience.

NursingNow is a global campaign, started in 2018, with the goal to improve health for all by utilizing and elevating the status of nurses.NursingNow is a global campaign, started in 2018, with the goal to improve health for all by utilizing and elevating the status of nurses (Holloway et al., 2021). The NursingNow mission is clear, stating “…nurses are vital agents of change who can improve health and transform health care” (Holloway et al., 2021, p. 4). The NursingNow initiative, along with The Future of Nursing 2020-2030 document, both call for nurses as leaders of collaborative efforts with other healthcare professions to promote health and well-being for all (Holloway et al., 2021; NASEM, 2021a).

The nursing workforce, as the last line of defense for patients, is at the center of the healthcare team; nurses interface with most professions and settings. NursingNow is a global campaign, started in 2018, with the goal to improve health for all by utilizing and elevating the status of nurses (Holloway et al., 2021). The NursingNow mission is clear, stating “…nurses are vital agents of change who can improve health and transform health care” (Holloway et al., 2021, p. 4). The NursingNow initiative, along with The Future of Nursing 2020-2030 document, call for nurses to serve as leaders of collaborative efforts with other healthcare professions to promote health and well-being for all (Holloway et al., 2021; NASEM, 2021a). Nurses have demonstrated that they are in an ideal position on the healthcare team to meet the additional demands placed on health services (e.g., contact tracing, testing, vaccine administration) and increased demand for staff, resources, policies, and supplies by the COVID-19 pandemic, all of which threaten an already overtaxed system (Digby et al., 2021). In this role, nurses are poised to lead efforts that advance health, including teamwork and collaboration efforts that promote the well-being of the team and strengthen the interprofessional pathway, and to centralize a system that partners education and practice, filling an acute human resource need in clinical settings.

These innovations engaged interprofessional students as members of the healthcare team to meet the healthcare needs of a population.The purpose of this article is to describe two nurse-led innovations that centralized and coordinated the connection of education and practice. These innovations engaged interprofessional students as members of the healthcare team to meet the healthcare needs of a population. We offer two exemplars that highlight the work and outcomes of nurse leaders in North Carolina to match health professions students with clinical practice settings to deliver services during the pandemic. The article illustrates opportunities for improvement and suggests recommendations for future work in disaster response and interprofessional workforce development. Our focus is on multiple health professions; however, we have taken the NursingNow mission to elevate nurses to leadership positions by highlighting specific opportunities to lead the call for a nurse-led flexible system that can proactively respond to patient care needs of a given population. Such a system would include patient care skills of various health professions across the continuum of learning.

Two Innovation Exemplars

The innovations were applied at different system levels: micro and meso.The innovations described within were implemented by the North Carolina Area Health Education Centers (AHEC) Program and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC-CH) Office of Interprofessional Practice and Education (OIPEP). Each connected education and practice and were developed to accomplish two goals: 1) provide support to the current healthcare workforce, and 2) establish clinical learning opportunities for interprofessional health students. Both efforts were designed as a win-win for health professions schools and practices, creating opportunities for each to meet the needs of the other while also preparing the pathway of future healthcare workers for collaborative practice upon workforce entry. Benefits of these innovations included meeting the immediate need for human capital and addressing the threat of burnout and stress of the future workforce through exposure to teamwork and collaboration. The innovations were applied at different system levels: micro and meso.

Microsystem Level Exemplar I: Local Health Professional Student Resource Matching Program

Exemplar I offers an illustration of a microsystem approach led by the assistant provost of the OIPEP, an RN, to build an innovation named within as the Local Health Professional Student Resource Matching Program at UNC-CH through the OIPEP. In 2018, UNC-CH established the OIPEP to position the university at the forefront of a nationwide movement to transform the way students are trained for the workforce and care for our communities. The OIPEP intentionally engaged professions external to healthcare, creating a campus wide initiative to advance health for all. Therefore, the OIPEP is a partnership between the schools of business, dentistry, education, medicine, nursing, pharmacy, public health, and social work; the department of allied health; and the health sciences library. Each partnering institution has a named IPEP director who works with the assistant provost for the OIPEP to support interprofessional endeavors that enhance the capacity and capability to improve health outcomes (OIPEP, 2021).

This course consisted of two parts, a didactic basic science and public health component and a service-learning component.Development and Implementation. In March 2020, the UNC-CH School of Medicine (SOM) created a course, Medical Management of COVID-19 to prepare medical and physician assistant (PA) students to deliver care to COVID-19 patients in an evolving healthcare system (NC AHEC, 2021). This course consisted of two parts, a didactic basic science and public health component and a service-learning component. The SOM partnered with the OIPEP to create the service-learning component of the course, using the Columbia COVID Student Services Corps ([Columbia SSC], n.d.) as its conceptual foundation.

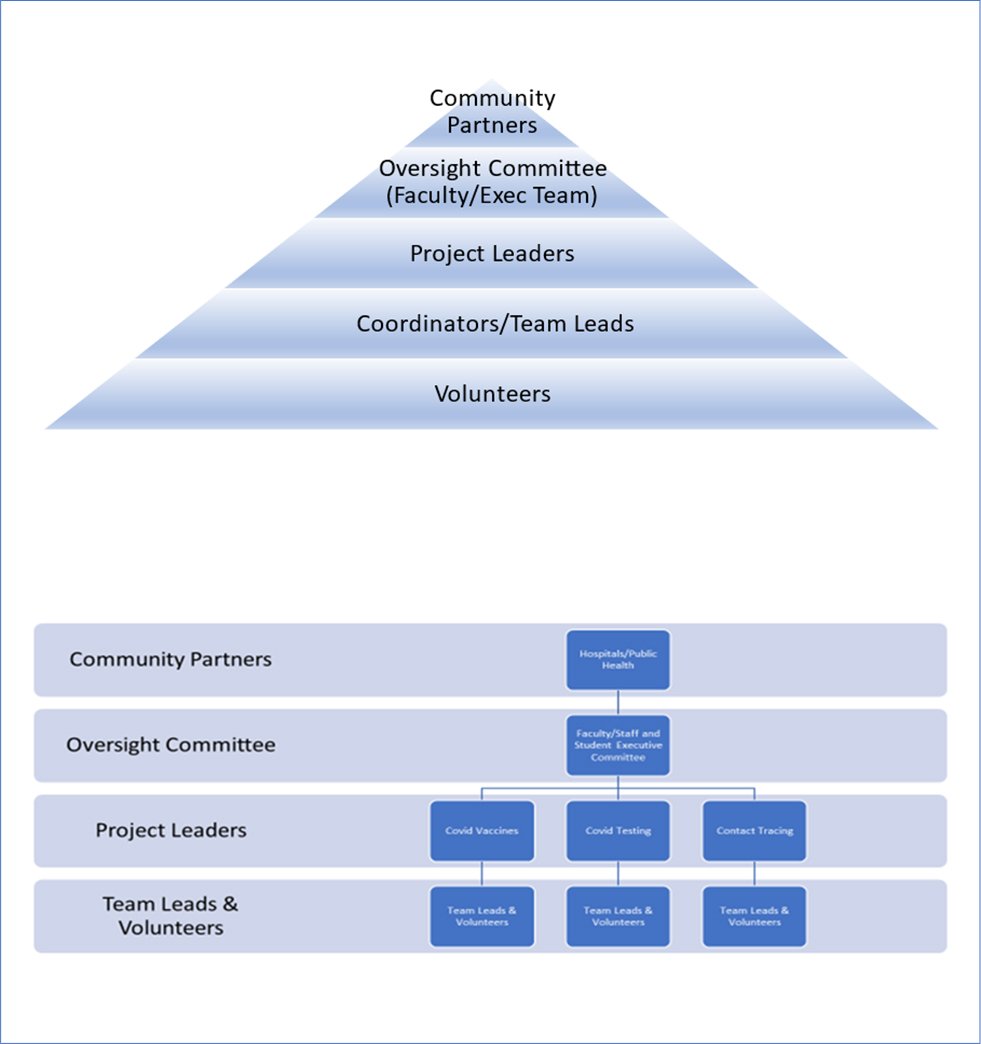

Figure 1. Conceptual Foundation of Service-Learning Component for Medical Management of COVID-19 Course (created by the authors)

Each opportunity was assigned a student lead, who was connected to the community...The Carolina COVID Students Services Corps (Carolina CSSC, n.d.) created opportunities for health professions students to partner with communities to address changing needs of first-line responders. Using listservs of community organizations, social media campaigns, and word of mouth, Carolina CSSC recruited organizations to submit their needs via a Google form, which Carolina CSSC staff then reviewed for skills and scope needed and placed a sign up list on a password protected website for students. Training and supervision needs were explicitly stated. Each opportunity was assigned a student lead, who was connected to the community, to address questions and quality improvement needs (see Figure 1).

In the original 4-week iteration of the Carolina CSSC, students made PPE kits, assisted with oversight of donning and doffing, ensured meal delivery, supported telehealth services, and even provided childcare for healthcare providers. The Carolina CSSC established a database where community partners and healthcare professionals could submit requests for service that were vetted by an interprofessional team of faculty and students and then posted on a secure website to allow matching of students with community needs. Carolina CSSC worked with NC AHEC to identify practice support needs, ultimately engaging 55 students with over 2000 patient telehealth encounters. Over 120 medical and PA students completed 2-4 hours of service each week, primarily in rural areas.

Recognizing the potential impact of this model, an executive team of students from nursing, public health, and medicine worked to create an infrastructure and implementation guide to build the Carolina CSSC as a sustainable organization with an interprofessional component (Zomorodi, 2020). When health professions students returned to the clinical practice setting with limitations in October 2020, pre-health students and those exploring health related careers were still limited due to restrictions on opportunities for volunteering and shadowing. Additionally, there was a great need to establish a COVID-19 testing center on campus to support the safe return of students, faculty, and staff at UNC-CH. Therefore, the OIPEP partnered with the Carolina Center for Public Service and NC AHEC to expand the model to one that engaged pre-health students as well as graduate and undergraduate students in a variety of disciplines, majors, and professions to volunteer their unique skillsets, thus maximizing interprofessional collaboration.

Pre-health students commented that opportunities through Carolina CSSC helped them to feel more connected during the pandemic...Accomplishments. The result of the Carolina CSSC efforts was an 1800 volunteer, student-led program that ultimately served over 27,000 hours to the community through COVID-19 testing centers; PPE kit making; data review; development of public health communications and education; and contact tracing. Student engagement for volunteers also focused on virtual shadowing experiences, reward systems, raffles, and the “CSSC of the Week” recognition. Pre-health students commented that opportunities through Carolina CSSC helped them to feel more connected during the pandemic, providing many with opportunities to engage in the service hour requirement needed to apply for a career in the health professions that they otherwise would not have had access to. To date, forty public health nursing students completed rotations with the CSSC as part of their public health course clinical requirements, and over 100 nursing students volunteered their time outside of class responsibilities.

Over 800 students, 300 of them undergraduate nursing students, provided 150,000 vaccines from January to June 2021.In December 2020, vaccines were introduced; and, with a student volunteer system in place, surrounding hospitals connected with the Carolina CSSC to engage students in vaccine efforts. Nursing, pharmacy, physician assistant (PA), emergency medical technician (EMT-2), medical, social work, and physical therapy students partnered with local hospitals, campus health, local health departments (LHDs), and mobile clinics to provide support in the vaccine effort. Over 800 students, 300 of them undergraduate nursing students, contributed to the administration of 150,000 vaccines from January to June 2021. In addition, undergraduate nursing, PA, and pharmacy faculty partnered with the OIPEP and Carolina CSSC to embed the vaccine effort into existing coursework. This effort allowed over 3,000 vaccines to be given by students at Campus Health services.

Mesosystem Level Exemplar II: Statewide Health Professions School Resource Matching Program

Exemplar II describes work at the mesosystem level led by the NC AHEC Director of Education and Nursing, also an RN, to build an innovation named within as the Statewide Health Professions School Resource Matching Program. The mission of the NC AHEC Program is to provide and support educational activities and services with a focus on primary care in rural and under-resources communities to recruit, train, and retain the workforce needed to create a healthy North Carolina (NC AHEC, n.d.). To move this mission forward, the NC AHEC established the NC Interprofessional Education Leaders Collaborative (NC IPELC) to facilitate communication, partnership, and teamwork among existing and future healthcare related IPEP initiatives within the state.

The NC IPELC represents approximately 46 health professions/sciences programs in NC plus 58 community colleges...The NC IPELC represents approximately 46 health professions/sciences programs in NC plus 58 community colleges, all with a health professions/sciences program. Its purpose is to recognize IPEP efforts of educators across the state and align strategies to avoid duplication and competition. Led predominantly by nurses on its executive committee, the NC IPELC is made up of interprofessional representatives from health professions/sciences programs in NC, including 2- and 4-year programs, community colleges, technical schools, colleges, and universities both public and private.

The goal is to develop a centralized systems approach to enhance interprofessional clinical learning environments.The NC IPELC created a platform to disseminate effective strategies for IPEP initiatives in faculty development, curriculum resources, and assessment and evaluation. The goal is to develop a centralized systems approach to enhance interprofessional clinical learning environments. Through resource pooling and coordination to capitalize on opportunities for collaboration among professions and between institutions in various clinical settings with high needs, especially rural and underserved areas. While the NC AHEC Program is a statewide program with robust relationships in education and practice across the state of NC, the main program office is situated at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC-CH). It is important to note that the position of the assistant provost of the OIPEP is partially funded by the NC AHEC Program to pilot IPEP efforts, such as the OIPEP exemplar, for statewide dissemination.

The Carolina CSSC model was a baseline or pilot model.Development and Implementation. In February 2021, the NC AHEC Program partnered with UNC-CH OIPEP to re-package and disseminate the “Medical Management of COVID-19” course through the NC IPELC for use in interprofessional health programs at institutions of higher education (IHE) throughout the state. Recognizing that school resources vary widely to meet the course service component, the NC AHEC Program used the opportunity to stimulate work towards the IPELC goal of a centralized systems approach to enhance interprofessional clinical learning environments. The Carolina CSSC model was a baseline or pilot model to build a statewide database at NC AHEC that focused on COVID-19 needs, with a specific focus on health equity, and assess the availability of interprofessional student resources in NC and community-specific needs for vaccination, contact tracing, testing, and general volunteer support.

Groups that have been economically or socially marginalized and under-resourced areas of the state were identified as targets and priorities.To build the database, health professions schools were engaged through the NC IPELC and regional AHEC Centers and asked to complete a 15-question survey that assessed skills, clinical hours, locations, and level of faculty oversight available and required for students. Simultaneously, local health departments (LHDs) and community-based organizations (CBOs) were asked to respond to a survey that assessed clinical needs related to their COVID-19 response. Groups that have been economically or socially marginalized and under-resourced areas of the state were identified as targets and priorities. Using this survey data, the NC AHEC Program leaders planned to match and connect skill needs of the community with the skills capital of IHE students and faculty.

Accomplishments. The statewide AHEC database effort resulted in 68 responses from faculty at IHEs in NC; this represented 48 institutions that have one or more health professions programs. Sixty-three (94%) respondents indicated that they had students available to assist in the COVID-19 response. The most common type of health professional student in the survey was Allied Health/Other (23%), including massage therapy, phlebotomy, imaging professions, respiratory therapy, physical therapy, athletic training, lab technicians, speech therapy, and emergency medical services. However, the single most common health professional student was prelicensure nursing (22%), including Licensed Practical Nursing, Associate Degree in Nursing, and Bachelor of Science in Nursing. The other 3 most common types of health professions students were nursing assistant (11%); medical assistant (10%); and social work (7%).

Students were available to assist in all 100 NC counties, with more available in urban than rural counties.Students were available to assist in all 100 NC counties, with more available in urban than rural counties. Because a skills-focused assessment was deployed, respondents were able to specify the COVID-19 related competencies that interprofessional students could perform. The most common roles that students were qualified to fill, as indicated by the respondents, were Screener and Patient Monitor (8.57% each); Educator (8.07%); Vaccine Runner (7.56%); Testing Runner (7.73%); and Patient Support (7.39%). Forty-five percent (45%) of respondents indicated a need for students to have both vaccine and COVID-19 testing training. Additional needs reported included training on documentation and site-specific guidelines.

In response to the need for vaccine training, an interprofessional group of public health, government, and nursing faculty were guided by the Orange County local health department to build a module that outlined a team-based approach to COVID-19 vaccines. This module was disseminated for statewide use in both academic and practice settings through the NC AHEC Program infrastructure (CAHEC, 2021).

Intense workloads and other demands on the current workforce precluded a significant response to the survey from clinical sites. Thus, the methodology quickly shifted from a “matching” system to an “introducing” system. In this approach, the data collected from schools were distributed statewide through various channels to promote introductions to skills that students could bring to clinical sites in need. Because of this ‘introducing’ method, measuring impact has been difficult. However, nearly all IPELC members reported student participation in COVID-19 relief efforts in both volunteer and clinical learning capacities. At least 11 new education and practice connections were made as a result of the statewide AHEC database, with an estimated five of those connections seemingly resulting in a partnership.

Discussion

While connecting education and practice was a tremendous resource to those sites that were able to capitalize on it, multiple barriers to student and school engagement became apparent in both the CSSC and the statewide AHEC database. Barriers included:

- the lengthy and meticulous process of obtaining affiliation and compliance agreements between the school and clinical site

- legal issues around student participation in clinical care outside clinical course requirements

- the need to travel to remote, rural locations to volunteer or participate in a clinical activity

- sites lacking the capacity to onboard students

- the need for liability waivers

- accessible and virtual training

- availability of faculty and staff to provide oversight and supervision

- lack of fit between student learning objectives and clinical sites

- the need for waivers for faculty to be able to travel (employee travel was prohibited for many schools) to provide oversight and supervision of students at clinical sites

This instability highlights the need to support academic-practice partnerships through a unified, system-wide approach...Since the beginning of the pandemic, the pendulum has swung from one extreme to another: initially, IHEs desperately needed clinical learning opportunities for health professions students in order to promote program completion or graduation, but healthcare settings were unable to accommodate students. Now, healthcare settings desperately need human capital to support the current workforce and promote health and well-being to the community, but IHEs are unable to respond directly to their needs due to the prioritization of meeting accreditation requirements and/or course objectives, lack of contracts or memorandums of agreement in place, semester plans already in full swing, and/or the absence of protected time or support to coordinate extra activities outside job responsibilities. This instability highlights the need to support academic-practice partnerships through a unified, system-wide approach that fluidly identifies and addresses the needs of the future and current healthcare workforce. Lessons from the two exemplars described within have led to recommendations for local, state, and national policy changes that address compliance, contracting, and accreditation; incentives for academic-practice partnerships; and the integration of the CSSC and the statewide AHEC database under a macro-system level health professional student corps. These recommendations, summarized in the table, apply to all health professions; however, they are particularly critical in nursing when considering the vast size, scope, and centralized position of the nursing workforce on the healthcare team.

Table 1. Recommendations for a Nurse-Driven Model for IPE Partnerships

|

Areas for Improvement |

Key Recommendations |

|

Compliance, Contracting, and Accreditation |

|

|

Incentives for Ongoing Partnerships |

|

|

Health Professions Student Corps |

|

Contracts, Compliance, and Accreditation Considerations

A contract at a clinical site is commonly between each individual health professions school and/or each clinical setting within a system. For example, a university with six different health professions schools would establish six different contracts with the partnering community institution. Separate contracts are resource-intensive and lack flexibility needed to engage students quickly and in an interprofessional context. This creates an inequity for small practice sites, especially those in rural and underserved areas. These facilities likely do not have the necessary resources to manage multiple contracts and compliance support to onboard students.

Broad agreements between state facilities (e.g., a statewide local health department system or state-facilities) and IHE systems (e.g., a community college, the state university system, and independent colleges and universities), instead of individual IHEs, would allow clinical sites to work easily with different health professions schools. Agreements could be based on need and availability and would enhance the ability of clinical sites and health professions schools to partner for interprofessional experiences.

To address regulations and safety guidelines, healthcare sites need to ensure that their workforce, including volunteers, students, faculty, and employees, meet compliance requirements. Compliance may include certain vaccines; training in health information privacy; infection control; universal precautions; and other common core educational requirements. Students who work in different settings, whether as volunteers or for a course requirement, have to fulfill compliance requirements for each clinical site. This often means completion of two or more training sessions for health information privacy and submission of vaccine status to multiple systems. In addition to duplicative training and paperwork, compliance managers in both the school and the partnering site must disseminate materials and manage completion; this significantly expands workload.

Compliance requirements may vary both between and within healthcare systems, and sometimes between health professions.Compliance requirements may vary both between and within healthcare systems, and sometimes between health professions. In addition, schools need to prioritize efforts to achieve compliance for student clinical placements rather than volunteer efforts, as this process is lengthy. As a result, volunteer opportunities would often have passed before students could be ‘vetted’ to participate. This again creates an inequity across sites, as well as individual professions. While some professions have compliance training that is current for over a year, others have to re-certify every rotation. Required oversight for students across professions varies greatly; a centralized database that identifies requirements would greatly assist with placement and on-boarding of students.

Alignment across and not just within systems, and between health professions, would greatly increase efficiency and effectiveness of student onboarding.Alignment across and not just within systems, and between health professions, would greatly increase efficiency and effectiveness of student onboarding. For example, alignment could lead to a universal standardized process and database for compliance that would allow flexibility and efficient transfer of student volunteers to sites where needs are greatest. Such a process would broaden opportunities to expose students to a variety of populations and communities even outside the pandemic. Nationally, a universal compliance system has potential to increase access to rural and underserved areas, where there is currently a workforce shortage. NC AHEC has a model for compliance standardization among nursing schools in NC and partnered institutions that could serve as a pilot for other professions and locations (Wake AHEC, n.d.).

Nationally, a universal compliance system has potential to increase access to rural and underserved areas...Due to varying interpretation of accreditation and licensing boards, both innovative initiatives described in this article often found it more difficult to get nursing students than other health professions students ‘at the table.’ This challenge was particularly true external to nursing student course requirements. In some cases, nursing students were required to have direct observation by an RN, limiting the number of students who could assist in workforce support efforts. In other instances, they were allowed to participate only if a faculty member was present, and with specific ratios of oversight (e.g., 1 faculty member to 4 nursing students) that are absent in other professions. Standardizing practice regulations and student oversight by skill instead of profession should be considered to maximize use of volunteers. For example, universal competencies and standardized supervision requirements for vaccine administration should apply to all professions. Because nurses are mainly responsible for vaccine administration, nursing professional organizations should lead these efforts.

Incentives for Ongoing Partnerships

Standardizing practice regulations and student oversight by skill instead of profession should be considered to maximize use of volunteers.The success of the Carolina CSSC and the statewide AHEC database was dependent on strong partners and a robust system development. NC AHEC was able to capitalize on existing relationships with health professions schools, state leadership, and clinical partnerships to establish and disseminate the student databases. Similarly, the success of the Carolina CSSC is due in large part to supportive institutional leadership; innovative and motivated faculty and students; and an established IPEP infrastructure that existed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Recognizing academic-practice partnerships through federal and state-level government resources and providing support for cooperative-like infrastructures, particularly in under-resourced and rural areas, will incentivize creativity and innovation for sustainability and promotion.

Many, if not most, health professions schools do not yet have dedicated resources for a central position to coordinate the interprofessional student activities...Many, if not most, health professions schools do not yet have dedicated resources for a central position to coordinate the interprofessional student activities that made the Carolina CSSC model so successful at UNC-CH (Forcina, 2020). As such, one recommendation is to incentivize ongoing partnerships that include fiscal allocation and formal faculty appointment for interprofessional coordination both in academic and practice settings. For non-university settings such as community colleges and technical schools, establishing interprofessional collaboratives across institutions, perhaps housed in local AHEC centers, would allow for efficient coordination of students in the event of a disaster and promote teaming skills that are particularly crucial in the current environment of workforce and resource shortages. As nurses span the entire healthcare continuum and are often in roles of care and team coordination, they are well-equipped to serve in an interprofessional leadership role in both academia and clinical practice.

Health Professional Student Corps

Despite broad recognition of the need to actively deploy health professions students in times of crisis and shortage, individual organizations, institutions, and clinical sites were still left responsible to ensure adequate training and supervision. While not insurmountable on a small scale, this certainly presents a barrier to student placement. When considered on a broader scale, this inefficiency and lack of standardization demonstrates how woefully underprepared the United States was to utilize students in any capacity. Thus, opportunities for service and experiential learning were missed; a missed opportuniy for students, the healthcare workforce, and the community alike.

...there were missed opportunities for service and experiential learning when this could have been a win-win for students and community partners alike.The formation of a national health professions student corps would allow ongoing interprofessional public health and disaster training, compliance tracking, and broad contracting and agreements that could be activated in event of emergency. The National Healthcare Disaster Certification (NHDP-BC™) from the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC) will no longer be available for attainment as of December 2022 for reasons not cited (ANCC, n.d.). However, this program could be re-imagined, providing an updated certification in the context of an interprofessional, population-based framework. Such a framework could focus on health equity as the basis for training and development of corps members.

Some of this work is underway. The National Student Response Network (NSRN), whose mission was to build a network of health students across the US that could be mobilized by their respective state and local public health departments and hospitals to support COVID-19 response efforts and beyond. This network was formed in March 2020. Within two months, the NSRN grew to 6,500+ students across all 50 states. The network became increasingly interprofessional, including students from nursing, pharmacy, and physician assistant programs; many others were represented in its student leadership and member network. (AONL, n.d.; Rodgers, 2020).

These students have potential to significantly and positively impact the communities in which they serve.The same obstacles that plagued the Carolina CSSC and the AHEC work eventually led to the dissolution of NSRN. Nevertheless, students from NSRN continue to express interest in a health professional student corps, showing that interprofessional students across the US are willing and able to serve. These students have potential to significantly and positively impact the communities in which they serve. To make their efforts sustainable and highly effective, there must be an infrastructure that guides practice connections, ensures safety, and offers liability protection. The infrastructure must support recommendations for compliance, contract standardization, and established academic-practice partnerships.

Call to Action

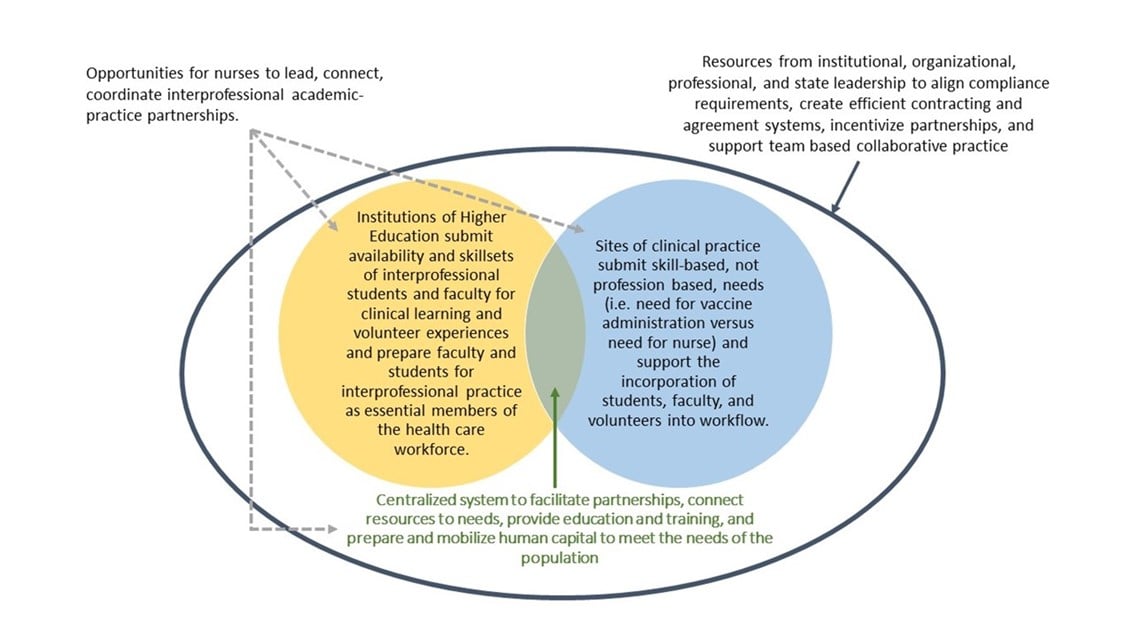

The Carolina CSSC and the statewide AHEC database were successful overall. However, opportunities for a more robust, high impact organization that mitigates the barriers to efficiency and effectiveness described could be addressed if these efforts were combined to form one, interconnected academic-practice partnership system (see Figure 2). The integration of a chapter-based model that assures student connections to IHEs would provide the opportunity for workarounds in liability; contracting and agreements; and oversight and supervision on the micro-system level. This would also provide the opportunity for promotion and support of academic-practice partnerships through AHEC centers, which are part of a national network, or similar organizations on the meso-system level.

Figure 2. Academic-Practice Partnerships Using and Interconnected, Centralized System (created by the authors)

On the macro-system level, this model connects health professions students to students and faculty in other professions...On the macro-system level, this model connects health professions students to students and faculty in other professions and other IHEs and provides a platform for mass, standardized training opportunities. Nurse leaders are obligated to embrace leadership of these efforts. Nearly half of nursing programs cite lack of clinical sites as a barrier to program growth (NLN, 2021), meaning that the largest existing healthcare profession and largest healthcare profession in training cannot thrive unless changes are made. Capitalizing on the sheer number of nursing programs in the US (as compared to other health professions), chapters of a National Interprofessional Health Student Services Corps, with proper funding and support, could be housed in nursing schools and coordinated by nurse leaders. Such an effort would require support from local AHECs to make the education and practice connections for academic-practice partnerships.

Conclusion

The NursingNow initiative, including NursingNow USA, asked nurses to be agents of change...The NursingNow initiative, including NursingNow USA, asked nurses to be agents of change, with one example being leaders of interprofessional teams (Holloway et al., 2021). This article has described two exemplars of nurse-led innovations in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic has shown the grit and determination of nurses, their influence and value to the public, and their unwavering and selfless compassion in a time of community need.

However, as the pandemic continues to challenge the healthcare workforce. Conditions have placed the nursing profession in crisis. We must invest in empowering the largest healthcare profession in the world to lead the way in innovation to reach every part of the public health population, both in “normal” times and during disasters. Developing this infrastructure would diminish issues related to contracts, agreements, compliance, accreditation, regulations, and incentives for community volunteer, academic, and practice partnerships. These issues are here to stay. We must utilize the lessons learned to build the healthcare system of the future, one that is collaborative, inclusive, and addresses health for all.

Authors

Jill Forcina, PhD, RN, CNE, CNL

Email: Jill_forcina@ncahec.net

ORCID ID: 0000-0002-6293-5149

Dr. Forcina is the Director of Education and Nursing at the North Carolina (NC) Area Health Education Centers (AHEC) Program. She is a PhD-prepared nurse with a clinical background in oncology and end-of-life care. She is a Clinical Nurse Leader, a Certified Nurse Educator, and Chair of the NC Interprofessional Leaders Collaborative. Dr. Forcina has been a key partner with stakeholders in NC in building the contact tracing curriculum and coordinating the engagement of student and interprofessional volunteers in the COVID-19 response.

Meg Zomorodi, PhD, RN, ANEF, FAAN

Email: meg_zomorodi@unc.edu

ORCID ID: 0000-0001-7394-8917

Dr. Zomorodi is Assistant Provost for Interprofessional Education and Practice at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She received a BSN and PhD from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Nursing. In 2014 she was selected as a Josiah Macy Faculty Scholar and is currently serving on the IPEC Expert Panel, “Leveraging the IPEC Competency Framework to Transform Health Professions Education.” She leads the Rural Interprofessional Health Initiative (RIPHI) and the Carolina COVID Student Services Corps, two programs that partner IP students with communities to focus on service and quality improvement.

Leah Morgan, PhD, RN

Email: MorganL4@queens.edu

Dr. Morgan is an Assistant Professor in the Presbyterian School of Nursing at Queens University of Charlotte. She received a joint BSN and PhD from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Nursing and is an alumnus of the Hillman Scholars in Nursing Innovation program.

Nikki Barrington, MPH

Email: nikki.barrington@my.rfums.org

Ms. Barrington is an MD-PhD student at Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science. She received a BS from the University of California, Santa Barbara and an MPH from the University of California, Davis. She is currently completing a PhD in neuroscience, studying neuroinflammation in traumatic brain injury and plans to specialize in neurosurgery. She is co-founder and Director of Operations for the National Association for Interprofessional Health Mentorship, Education, and Service (NAIHMES), a student organization whose mission is to promote health equity by training future healthcare providers to address the social determinants of health utilizing an interprofessional framework.

References

American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2020). Fact sheet: Nursing shortage. https://www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/42/News/Factsheets/Nursing-Shortage-Factsheet.pdf

American Journal of Managed Care. (2021, January 1). A timeline of COVID-19 developments in 2020. https://www.ajmc.com/view/a-timeline-of-covid19-developments-in-2020

American Nurses Credentialing Center. (n.d.). National healthcare disaster certification. https://www.nursingworld.org/our-certifications/national-healthcare-disaster/

American Organization for Nursing Leadership. (n.d.). NSRN offers nationwide COVID-19 support. https://www.aonl.org/news/SNRN-offers-nationwide-COVID-19-support

Bachynsky, N. (2020). Implications for policy: The triple aim, quadruple aim, and interprofessional collaboration. Nursing Forum, 55(1), 54-64. https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12382

Bodenheimer, T., & Sinsky, C. (2014). From triple to quadruple aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. Annals of Family Medicine, 12(6), 573–576. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1713

Carolina Covid Student Services Corps. (n.d.). Carolina COVID-19 Student Services Corps (CSSC). https://ipep.unc.edu/students/carolina-covid-19-student-services-corps-carolina-cssc/

Charlotte Area Health Education Center. (2021). Volunteer training for COVID-19 vaccination sites. https://www.charlotteahec.org/event/65572

Columbia Student Service Corps. (n.d.). Columbia Student Service Corps (CSSC). https://www.vagelos.columbia.edu/education/student-resources/covid-19-student-service-corps-cssc

Digby, R., Winton-Brown, T., Finlayson, F., Dobson, H., & Bucknall, T. (2021). Hospital staff well-being during the first wave of COVID-19: Staff perspectives. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 30(2), 440-450. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12804

Fogg, N., Wilson, C., Trinka, M., Campbell, R., Thomson, A., Merritt, L., Tietze, M., & Prior, M. (2020). Transitioning from direct care to virtual clinical experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Professional Nursing, 36(6), 685-691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2020.09.012

Forcina, J. (2020, January). NC interprofessional education leaders collaborative baseline needs assessment [Unpublished presentation]. North Carolina Area Health Education Centers Program.

Health Professions Accreditors Collaborative. (2019). Guidance on developing quality interprofessional education for the health professions. Health Professions Collaborative. https://healthprofessionsaccreditors.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/HPACGuidance02-01-19.pdf

Holloway, A., Thomson, A., Stilwell, B., Finch, H., Irwin, K., & Crisp, N. (2021). Agents of Change: the story of the Nursing Now campaign. Nursing Now/Burdett Trust for Nursing. https://www.nursingnow.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Nursing-Now-Final-Report-Executive-Summary.pdf

Jones, C. B., Forcina, J., & Tran, A. K. (2021). Pandemic health care workforce study. North Carolina Area Health Education Centers Program.

Langlois, S., Xyrichis, A., Daulton, B. J., Gilbert, J., Lackie, K., Lising, D., MacMillan, K., Najjar, G., Pfeifle, A. L., & Khalili, H. (2020). The COVID-19 crisis silver lining: Interprofessional education to guide future innovation. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 34(5), 587–592. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2020.1800606

Michalec, B., & Lamb, G. (2020). COVID-19 and team-based health care: The essentiality of theory-driven research. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 34(5), 593–599. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2020.1801613

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2021a). The Future of Nursing 2020-2030: Charting a Path to Achieve Health Equity. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25982

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2021b). Lessons learned in health professions education during the COVID-19 pandemic, Part 1: Proceedings of a workshop. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26210

National League for Nursing. (2021). NLN biennial survey of schools of nursing academic year 2019-2020: Executive summary. https://www.nln.org/docs/default-source/uploadedfiles/default-document-library/nln-biennial-survey-of-schools-of-nursing-2019-2020.pdf

North Carolina Area Health Education Centers. (2021). NC AHEC and UNC School of Medicine Offer Virtual Course Curriculum in Medical Management of COVID-19. https://www.ncahec.net/news/nc-ahec-and-unc-school-of-medicine-offer-virtual-course-curriculum-in-medical-management-of-covid-19/

North Carolina Area Health Education Centers. (n.d.). Our Mission. https://www.ncahec.net/about-nc-ahec/our-mission/

Redden, E. (2020, June 25). Clinical education in a pandemic era. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2020/06/25/clinical-education-starts-resume-haltingly-many-health-care-fields

Reeves, S., Fletcher, S., Barr, H., Birch, I., Boet, S., Davies, N., McFadyen, A., Rivera, J., & Kitto, S. (2016). A BEME systematic review of the effects of interprofessional education: BEME Guide No. 39. Medical Teacher, 38(7), 656-668. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2016.1173663

Rodgers, K. (2020, May 20). National student response network linking volunteers to health professionals. NACCHO.org. https://www.naccho.org/blog/articles/national-student-response-network-linking-volunteers-to-health-departments

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Office of Interprofessional Education and Practice. (2021). About Us. https://ipep.unc.edu/about-us/

Wake AHEC. (n.d.). Consortium for Clinical Education and Practice. https://www.wakeahec.org/hctriangeclinical.htm

World Health Organization. (2010). Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/70185/WHO_HRH_HPN_10.3_eng.pdf

Zomorodi, M. (2020). Carolina COVID-19 Student Services Corps. Association of American Medical Colleges. https://www.aamc.org/resource-library/collaborative-student-volunteer-and-service-projects/carolina-covid-19-student-services-corps