It is often said that modern-day nursing and midwifery was founded on the spirit of activism. Yet, historically, the link between nursing and activism has been inconsistent. Nursing Now USA was created in response to a global campaign launched in 2020 by the World Health Organization to mark the Year of the Nurse and Midwife. A goal of this initiative is education about how contemporary nurses serve as leaders in healthcare in the United States. This article describes the methods and results of a scoping review that sought to explore the current state of the science, key concepts, and operationalization of activism in nursing. The general consensus in the literature is that the profession of nursing has deep roots in activism, but a lack of a clear definition of activism and operationalization in policy, practice, research, and academic settings likely limits active engagement by many nurses. The current state of nurse activism is more subtle, often unseen, and non-confrontational compared to the participation and contribution of nurses from the 1900s to the 1980s. We identified barriers and facilitators to activism in nursing and our discussion includes implications for nursing practice, education, and leadership.

Key Words: Nursing Now USA, nurse activism, activist, social movement, social justice, political movements, nurses and midwives, United States, professionalism

A goal of this initiative is education about how nurses serve as leaders in healthcare in the United States.Nursing Now USA (ANA, n.d.) was created in response to the global Nursing Now campaign launched by the World Health Organization in 2020 ([WHO], n.d.) to mark the Year of the Nurse and Midwife. A goal of this initiative is education about how nurses serve as leaders in healthcare in the United States. In response to the Nursing Now USA call for commissioned papers exploring the contemporary understanding of nursing, this article describes a scoping review that spotlights innovations of nursing leadership through exploration of the topic of nurse activism. Activism can be defined as, “The policy of active participation or engagement in a particular sphere of activity; spec. the use of vigorous campaigning to bring about political or social change” (Oxford University Press, n.d.).

It is often said that modern-day nursing and midwifery were founded by activists.It is often said that modern-day nursing and midwifery were founded by activists (Florell, 2021; Pollitt, 2018). Yet, historically, the link between nursing, midwifery (which we will hereafter refer to as “nursing”), and activism has been inconsistent. Nurse pioneers, such as Lavinia Dock, Mary Seacole, and Lillian Wald pushed social boundaries and gender norms to fight for health equity for marginalized and disenfranchised communities (Forrester, 2016). More recently, however, leaders in the nursing profession have been hesitant to be associated with activism, focusing on individual health needs rather than systemic or structural inequities, health policy, or social justice (Boutain, 2005; Buettner-Schmidt & Lobo, 2012; Florell, 2021; Moorley et al., 2020).

Multiple reasons for this change have been suggested, including a shift in focus from public health to individual health behaviors (Boutain, 2005); lack of related content in nursing curricula (Florell, 2021; Habibzadeh et al., 2021); and/or a de facto focus on the biomedical model of care that centers disease over social determinants of health (Rudner, 2021). The perceived association of the nursing profession with oppressed group behaviors, where horizontal violence is common and group norms center on a status quo of silencing non-conformist views, may also explain a lack of activism in recent years (Matheson & Bobay, 2007; Purpora & Blegen, 2012).

The perceived association of the nursing profession with oppressed group behaviors...may also explain a lack of activism in recent years.No matter the reasons, this hesitancy represents a missed opportunity. As the largest segment of the healthcare workforce, nurses hold significant potential and collective power to leverage activism as one means to usher in meaningful community, systems, and structural changes (Dickman & Chicas, 2021). Although there is no universally recognized definition of nurse activism, a recent concept analysis (Florell, 2021) defined it as “the expenditure of personal energy and social or political capital to address upstream and downstream determinants of health” (p.138). This recent definition allowed us to specify that activism in nursing is an action-oriented activity rather than just a concept or a theory.

Three nurses are currently serving in Congress...a testament to the changing perception and role of nursing on the national stage.The time for inaction is over, evidenced by both leaders in the nursing profession and current changes across the United States (U.S.). For example, recommendations from both the American Association Colleges of Nursing Essentials ([AACN], 2020) and the American Nurses Association (ANA) Code of Ethics (Fowler, 2021) suggest growing synergy and momentum to rejuvenate the conversation about nursing activism. AACN and ANA have each included advocacy and policy as key components of nursing and encouraged nurses to participate in, and even lead, political processes (VandeWaa et al., 2019). Three nurses are currently serving in Congress (Cori Bush, D-MO; Eddie Bernice Johnson, D-TX; and Lauren Underwood, D-Il), a testament to the changing perception and role of nursing on the national stage.

Furthermore, the disproportionate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people of color has illuminated the role of structural racism on long-standing health disparities in the US that nurses have witnessed on the front lines. The urgent need to address these issues has pushed leaders in the profession to examine the role of nurses to lessen or perpetuate disparities, including the willingness to embrace or desire to avoid activism.

The historical roots in activism and social justice inherent in the profession of nursing has informed the central purpose of this scoping review: to explore what is known about activism in nursing. Our secondary goals were to clarify key concepts and identify gaps in the literature.

Methods

Design

A scoping review is a useful method to explore the state of the literature in an identified research area without focusing on critical appraisal (Sucharew & Macaluso, 2019). Thus, scoping reviews do not make conclusions on the relative strength or weakness of an existing body of literature but rather serve as a ‘jumping-off point’ for further exploration. This review employed a five-stage scoping review methodology (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005) with the following steps: (1) identify a research question, (2) identify existing literature, (3) select studies for inclusion, (4) extract data from included studies, and (5) synthesize, summarize, and report results. Our research question was, “How is activism amongst nurses captured in the peer-reviewed literature?”

Literature Search

Search terms for activism included terms such as activist, social movement, political movement, and social justice.An electronic literature search was undertaken with the assistance of a health librarian using the following databases: Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PsychInfo, Embase, PubMed, and Global Health. Search terms for activism included terms such as activist, social movement, political movement, and social justice. We limited the search to professional nursing cadres such as registered nurses, midwives, licensed practical nurses, advanced practice nurses, and certified registered nurse anesthetists (CRNAs). These terms were selected based on a preliminary review of the literature performed to find commonly used words and synonyms.

...papers that addressed activism outside of the US were excluded.Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria. Inclusion criteria included articles that were (1) peer-reviewed and published, (2) written in English, (3) focused on professional nursing cadres in the US, and (4) focused on the operationalization of activism. Conference abstracts and non-peer-reviewed articles, such as op-eds and commentaries, were excluded. Publications focused on advocacy, engagement, and solely the conceptualization of activism were also excluded. Because the primary population of interest was nurses and midwives, we excluded certified nursing assistants and non-nursing professionals (e.g., community health workers). To standardize the sociopolitical context of nursing activism, papers that addressed activism outside of the US were excluded. Our search was not limited to any timeframe so as to capture all relevant articles. The Supplemental Material link below provides the full list of inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Supplemental Material: Eligibility Criteria

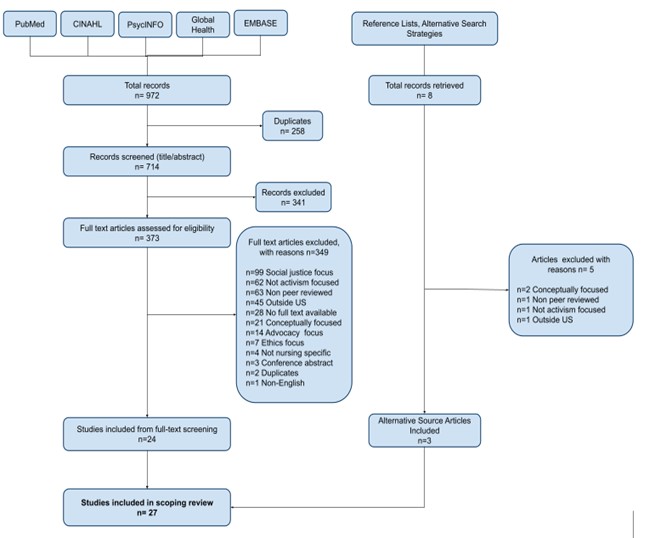

Search Results and Screening for Sample. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) diagram was used to report the search results (Figure 1). The initial search resulted in 972 papers. After duplicates were removed, two authors, working independently, initially screened the title and abstract of 714 articles. Disagreements were considered by a third author or the whole team for discussion and resolution. A total of 341 articles were removed in the title and abstract screening, leaving 373 articles for full-text review. Of these, 349 were removed after two authors independently reviewed the full texts, leaving a total of 24 relevant studies. In addition, we identified eight articles from manual reference list searches. Of these, three articles met the inclusion and exclusion criteria; thus, the final scoping review sample consisted of 27 articles.

Figure 1.

Data Analysis

...articles were categorized by commonalities, differences, and identified themes.Data extraction followed the Arksey and O’Malley (2005) scoping review guidelines. As such, we extracted data specific to the research questions for each included article. Three authors initially analyzed all articles together with no distinctions between article type, focus on a specific population or nursing specialties, or geographic location. Through data analysis, team-based discussions, and the organization of data into tables, articles were categorized by commonalities, differences, and identified themes. The three authors subsequently re-analyzed articles according to these themes to enable synthesis. Final conclusions and implications for research, policy, and practice were reached via consensus.

Results

Characteristics of Included Studies

Articles included in this review (n = 27) presented either examples of or recommendations for nursing activism. Individual study characteristics (e.g., design, geographic location of either a study or author affiliation at the time of publication, key players, and type of activism) are summarized below in the Supplemental Material link. Of the papers, 16 were non-databased (10 reports and 6 peer-reviewed editorial/commentary). The 10 non-databased reports were either descriptions of actions taken by a group of nurses or professional nursing organizations (Johnston & Landreneau, 2016; Ziehm et al., 2019) or call for action reports (Coleman, 2020; Des Jardin, 2001; Dickman & Chicas, 2021; Effland & Hays, 2018; Effland et al., 2020; Gordon, 2016; Gordon et al., 2016; Quinn et al., 2019).

Supplemental Material: Characteristics of the Studies Included in the Review

The 11 data-based papers were historical reviews (n=3), qualitative studies (n =3), pretest/posttest, quasi-experimental designs (n = 2), mixed methods (n=1), and cross-sectional quantitative studies (n = 2); specific study designs categorized as such can also be found in the aforementioned Supplemental Material link. Most of the papers focused on practice (n = 9), followed by education (n = 8), and policy (n = 5). Five papers focused on a combination of two areas: education and practice (n = 2), policy and practice (n = 2), or education and policy (n = 1). Of note, all articles were published after 2001, with more than half (n = 16, 59%) published since 2018.

The majority of the key actors within nursing activism in the existing literature were nursing students and faculty.The majority of the key actors within nursing activism in the existing literature were nursing students and faculty. Nursing organizations (e.g., California Association of Colleges of Nursing) and nurse leaders were involved in nursing activism to a lesser extent. Lastly, the population of interest or activism cause was often omitted (n = 20). Of those articles that reported a cause or population of interest, causes were listed as racial identity and racism (n = 3), professional organizations (n = 3), and victims of violence (n = 1).

Definition of Activism. Though we excluded articles that focused solely on the definition of activism, we sought to examine the consistency of the definition and how it is operationalized in the nursing literature (see Table 1). We found that activism was often not defined in the papers; only 8 of 27 (30%) included either implicit or explicit definitions or descriptions. When activism was explicitly defined (n = 3; 11%), it was discussed along with advocacy and allyship. For example, Zuzelo (2020) explained that activism, allyship, and advocacy were a commitment to challenge injustice and inequity at three levels of intensity and action. Zuzelo (2020) defined an activist as one who was energetically engaged in action intended to right wrongs that have led to or perpetuated injustice, inequity, and sociopolitical disparity.

Table 1. Operationalized Definitions of Activism Included in the Studies

|

Explicit |

Implicit |

|

|

More often, activism in nursing was discussed implicitly by a description of moral and ethical caring actions taken.Nursing Activism. Nursing activism was also considered a type of nursing care delivery, which intervened in a range of factors that influence health, as well as the translation of caring into actions at organizational, state, and federal levels (Rains & Barton-Kriese, 2001). More often, activism in nursing was discussed implicitly by a description of moral and ethical caring actions taken (n = 5). For example, Watson (2020) and Terry (2019) both described nursing activism as a call to address moral, social, and sacred injustices by honoring nursing focus on person, environment, and universe as one. In addition to those articles that included definitions, activism was also used interchangeably with concepts such as political involvement (Byrd et al., 2012; Des Jardin, 2001) and advocacy (Effland et al., 2020).

Summary of Findings

As we sought to provide an overview of the landscape of activism in nursing, the synthesis process revealed a distinction between databased research and non-databased articles. We categorized our findings by study methodologies to clearly delineate past actions versus future recommendations and thoughts about nursing activism. Results were grouped thematically into sections detailing policy, practice, research, academic findings, and ways in which nurses have participated in and talked about activism. Concise descriptions of each category are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Nursing Activism in Action and Future Recommendations

|

|

Databased Research |

Non-Databased Articles |

|

Policy |

|

|

|

Practice |

|

|

|

Education |

|

|

|

Research |

|

|

Databased Research. Review of the research papers demonstrated several past and current actions of nurse activists from various historical social justice movements, as well as contributions to recent practice and policy engagement. Historically, some activists harnessed their identities as nurses to inform policy development, especially for civil rights and social justice. For instance, nurse activists, such as Lavinia Lloyd Dock, Mary Bartlett Dixon, Sarah Tarleton Colvin, and Hattie Frances Krugersuch, were active in the suffrage movement and shifted legislative action and decisions related to women's right to vote (Pollitt, 2018). These nurses understood the link between voting rights and healthcare and were also vocal supporters of other laws supporting the health and safety of women. Such examples included the Maternity and Infancy Protection Act in 1921, which was passed a few years before voting rights of women were won.

Historically, some activists harnessed their identities as nurses to inform policy development...More recently, nurses have used their voices to urge city councils to advocate for public health interventions; become involved in environmental health initiatives; marched in Black Lives Matter protests; and created documentary films to chronicle injustices (Johnston & Landreneau, 2016; Terry & Bowman, 2020; Weitzel et al., 2020). In these efforts, nurses described their positions as community members and leaders, and their commitment to public health, as points of motivation and leverage in their activism.

In practice, nurse activists spoke of bearing witness to others' suffering and stepping outside of traditional roles to work to fix the broken system or ensure equal treatment. Examples of nurse activism in practice include the creation of a maternal care coalition (Maldonado, 2014); the nationwide Domestic Violence Education Project (Paluzzi et al., 2000); and the development of the sexual assault medical forensic exam in the 1970s and 80s (Morse, 2019). In education, incorporating policy action as a part of class requirements (e.g., capstone projects or attending a lobby day), has been well-received by nursing students (Byrd et al., 2012). Poole et al. (2019) also found that inclusion of advocacy education in CRNA curriculum was strongly associated with the students’ own political advocacy involvement (r = 0.48; p = 001).

...undergraduate nursing student political astuteness was associated with school administrator and faculty involvement.Similarly, undergraduate nursing student political astuteness was associated with school administrator and faculty involvement (Rains & Barton-Kriese, 2001). With further exploration, the researchers found that nursing students were interested in activism, focusing on the needs of the people they served and cared for (e.g., testifying at school board hearings, advocating for changes to institutional policy) but did not have a deeper level of understanding policy around activism compared to political science students (Amiri & Zhao, 2019). Lastly, empirical evidence of the role and structure of nursing activism is limited in research. Only one study was identified that utilized community-based participatory research of nurses' assessment and intervention for community environmental exposure (Amiri & Zhao, 2019).

Non-Databased Articles. The majority of recommendations for nurse activism found in literature were not based upon research; these focused on inclusion and expansion of curricular content about anti-racism, health equity, and social justice in all levels of nursing education. This collective call for expansion of nursing education to incorporate political, professional, and/or personal activism involves the active participation of faculty and students. Articles included calls to action and provided examples of policy and activism-focused modifications to nursing curricula, such as encouraging community engagement, providing opportunities to attend events and public speaking, and teaching students about the legislative process.

The majority of recommendations for nurse activism found in literature were not based upon research...Intentional recruiting and retaining students of color to increase diversity in the nursing workforce was recommended (McSpedon, 2020). Other recommendations included examining the impact of changes to courses/curricula on nursing activism on a larger scale using methods like community-based participatory research (Amiri & Zhao., 2019; Poole et al., 2019); conducting action-oriented activism through direct engagement with policymakers and political legislators; and/or connecting directly with communities (Quinn et al., 2019; Ziehm et al., 2019). Finally, nurses' professional mandate and ethical responsibilities to address injustice and inequities were highlighted across several articles as a basis for them to engage in activism (Morin & Baptiste, 2020; Weitzel et al., 2020).

Barriers and Facilitators to Activism by Nurses

Several barriers and facilitators to nursing activism were identified at both individual and systems levels. These are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Barriers and Facilitators to Activism in Nursing

|

|

Barriers |

Facilitators |

|

Individual-level |

|

|

|

Systems-level |

|

|

Tension between one’s beliefs in doing what was right and supporting and fulfilling nursing roles was also a factor.Barriers. At the individual level, concerns about being a lone voice; risk of bullying; and feeling unsafe and overwhelmed by the magnitude of current social, political, environmental and/or healthcare issues impeded participation in activism. Tension between one’s beliefs in doing what was right and supporting and fulfilling nursing roles was also a factor. Other barriers included a lack of knowledge, preparation, and guidance about how to be an effective activist. Effland et al. (2020) discussed how some nurses felt they did not know what steps to take to effect meaningful change, which led them to rationalize taking no actions at all or delaying activist behaviors.

At the system level, both retaliation for ‘going against the grain’ or staking out a position contrary to those of powerful people and loss of employment were barriers (Des Jardin 2001; Watson, 2020). Discriminatory culture, systemic racism, and lack of organizational support discouraged nurses from participating in activism (Maldonado, 2014). Another barrier was the persistent public image of nurses as subservient and ‘mothers,’ limiting nurses’ beliefs on their own capacity to be involved in policy changes and activism (Des Jardin, 2001). At times nurses experienced tension between the perceived role of nurses and their individual values and beliefs. For example, a forensic nurse felt a conflict at times as both a forensic investigator and a caregiver, two roles they identified as different from one another (Morse, 2019).

At the individual level, the sense of moral responsibilities, nursing ethics, and professional duties propelled nurses to be involved.Another barrier stemmed from overlapping policy and politics. By definition, politics requires action as a part of a governing body, whereas policy is the plan for action (Merriam-Webster, n.d.). The intersection of policy and politics in nursing practice led to a general lack of involvement from political apathy, a sense of powerlessness, and nurses’ lack of knowledge about the process (Byrd et al., 2012; Coleman, 2020; Rains & Barton-Kriese, 2001; Zauderer et al., 2008; Zuzelo, 2020).

Facilitators. We identified several facilitators for nurse activism in the literature. At the individual level, the sense of moral responsibilities, nursing ethics, and professional duties propelled nurses to be involved (Des Jardin, 2001; Effland et al., 2018; McSpedon, 2020; Settle, 2014; Wall, 2009). Settle (2014) found that nurses with a greater concern for the ethical aspects of their clinical practice, an increased perception of their influence regarding ethical decision-making, and a heightened awareness of their institution's ethical resources were more likely to engage in nurse activism. In addition, participation in public policy as a part of educational curricula was associated with political astuteness, identifying the need for tailored educational curricula for nursing students (Byrd et al., 2012).

Inclusive and supportive practice settings that enable nurses to recognize ethical dilemmas were highlighted as important facilitators.At the system level, self-empowerment emerged from knowledge by nurses that individual actions can also generate collective action and lead to eventual changes. The reputation of nursing as a caring profession also facilitated activism (Des Jardin, 2001). Inclusive and supportive practice settings that enable nurses to recognize ethical dilemmas were highlighted as important facilitators. However, most facilitators at the system level involved education and training. Use of technology (e.g., emails to officials or reading pieces of legislation available online); having mentors and role models for students and novice advocates; skill-building education; and collaboration with other disciplines also facilitated nurses to become actively involved in the pursuit of justice (Amiri & Zhao, 2019; Maldonado, 2014; McSpedon, 2020; Rains et al., 2001; Zaurader et al., 2008; Zuzelo, 2020).

Discussion

...the concept of activism was often used interchangeably with terms such as advocacy and political involvement...In this scoping review, we sought to understand what is currently known about activism in nursing. We found that nursing activism was largely undefined in the literature, with significant variation based on interpretation. As well, the concept of activism was often used interchangeably with terms such as advocacy and political involvement, particularly after 1990. Though terms such as advocacy are discussed synonymously with activism, they are not the same. Advocacy is to publicly support an issue or plead a case on someone else’s behalf (Merriam-Webster, n.d.). Advocates help to bring attention to an issue and support the activist. The lack of a standardized definition prevents a nuanced understanding of the broad spectrum of activities that encompass nursing activism and accepted variables for activism research.

This review found that the body of literature on nursing activism consists of a blend of articles describing historical or present-day activism and articles providing future recommendations for nurses to engage in activism. Historically, nurses actively contributed to bringing legislative change in the suffrage and civil rights movements; improved access to healthcare for women and infants; and developed forensic nursing. Although activism is typically associated with political mobilization such as protests, lobbying, and interactions with legislators and policy, activism in nursing education was also described in the literature (Byrd et al., 2012; Coleman, 2020; Effland et al., 2020; Gordon et al., 2016; McSpedon, 2020; Poole et al., 2019; Rains et al., 2001).

Within nursing education, incorporating curricular changes to include activism and advocacy and working with communities to address health disparities or inequities were the most prominent methods to engage in activism (Amiri & Zhao, 2019; Morin & Baptiste, 2020; Zaurader et al., 2008). Recommendations for modifying curricula included: (1) introducing concepts such as anti-racism and critical race theory to faculty development and courses across curriculum; (2) integrating non-health related content from the humanities into nursing courses to orient students to concepts such as racism, power, and privilege in U.S. society and the direct impacts on health; and (3) studying the impact of curricular change on nursing activism (Coleman, 2020; Des Jardin, 2001; Effland & Hays, 2018; Effland et al., 2020; Gordon et al., 2016; McSpedon, 2020).

Nursing faculty and administrators have been identified as key elements of nursing activism but may lack the education and experience...To enact these changes, capacity building for students, faculty, and related stakeholders is required. While nursing students seem genuinely interested in the populations they serve and want to become more involved in political activism, some may lack the political astuteness and education needed to understand or impact policy. Nursing faculty and administrators have been identified as key elements of nursing activism but may lack the education and experience necessary to impact change (Effland & Hays, 2018; Zauders et al., 2008). Partnering with experienced activist groups locally to build capacity is one place to begin.

Paolo Friere’s “Pedagogy of the Oppressed” (2018) may also serve as a useful framework to integrate activist strategies into nursing education and practice as well as promoting health equity. Friere’s theory states that people become oppressed when they are dehumanized by institutions and/or social structures that objectify them. Oppressors see humans as objects; by suppressing individuals, an ‘ownership’ model prevails whereby the oppressor has control over the oppressed. This model may be conscious or unconscious in its realization in the real world. Overcoming oppression begins with acquiring knowledge about the concept of humanization itself to avoid becoming an oppressor. Identifying oppressors together requires working together to be free from oppression. The goal is not only empowerment of the oppressed, but to become fully human.

Understanding the source of the oppression from the view of the oppressed is critical; consequently, this methodology is adaptable to a variety of cultures and contexts. Freire (2018) stated that once the oppressed understand their own oppression and discover their oppressors, the next step is dialogue, or discussion with others to reach the goal of humanization. Promoting activism in nursing, therefore, becomes a tool for overcoming oppression both experienced by nurses and those whom they serve. Recognizing and remembering the humanity of each person cared for by a nurse is a first step that every member of the profession can take, followed shortly thereafter by naming sources of oppression they experience. This is a difficult thing to do in the face of structures and systems that discourage this practice. Nonetheless, it is a place to begin. For those who already integrate this practice into their work, the next step is broader action to dismantle sources of oppression and potential oppressors within and outside of the profession that were highlighted in this review.

Based on our findings, recommendations for individual nurses and leaders in the profession to take include: (1) actively recruit and retain nursing students of color while working to diversify the nursing workforce with a focus on historically black colleges and universities; and (2) working to further engage with communities, increasing political acumen to connect with policymakers and legislators (Coleman, 2020; McSpedon, 2020; Quinn et al., 2019; Ziehm et al., 2019).

Nursing history is full of rich accounts of active participation by nurses in social justice movements, healthcare activism, and women’s rights from the 1900s until the 1980s. Compared to this history, present-day activism in nursing has transformed into more subtle and non-confrontational activities such as lobby days, meeting with legislators, and discussing patient advocacy within the confines of the current healthcare system, (as opposed to nurses at the forefront calling for change).

In what may be a turning point, our professional collective response to conditions wrought and revealed by the COVID-19 pandemic has marked a reemergence of historical activism by nurses for health equity and social justice. The COVID-19 pandemic illuminated the role of nursing and has put nurses front and center in speaking about poor working conditions, safer staffing ratios, and personal protective equipment needed to effectively care for patients and maintain personal safety (Morin & Baptiste, 2020). These demands were often met with hostility from employers and threats of termination (Morin & Baptiste, 2020). It is yet to be determined whether nursing activism in this area will result in a sustained cultural change in the profession, but it is a sign of a potential rebirth.

Implications for Nursing Practice, Education, and Leadership

Nursing Practice. For nurses to gain experience advocating for social issues, they need to seek experiences outside of the workplace. These experiences often are unpaid and tied to participation in nursing organizations. The literature shows that undergraduate nursing students are unaware, or just slightly aware, of the relationship between the nursing profession and public policy (Amiri & Zhao, 2019). Many nurses and nursing students are not involved in professional nursing organizations. For example, fewer than 10% of American nurses are members of the American Nurses Association or another professional organization (Black, 2014). This presents a tremendous opportunity for nursing organizations to partner with colleges, universities, and employers to not only promote the benefits of membership, but also the role they play in representing the interests of the profession at local, national, and international levels.

For nurses to gain experience advocating for social issues, they need to seek experiences outside of the workplace.Nurses must do a better job to balance the juxtaposition of the role of an employee who represents an institution and the activist role to speak for important social, environmental, and political causes. Silencing of nurses by employers, the hierarchy within organizations, and insufficient interprofessional collaboration is detrimental to individual nurses and the profession. This can lead to unsafe working conditions, nurse burnout, moral distress, and ineffective policymaking at local, national, and international levels (Busariet al., 2017; Moss et al., 2016).

Nursing Education. Findings from our review suggest that nurses need to increase their knowledge, skills, and attitudes and turn their service-oriented mindset towards social activism to have a larger voice in important issues related to the future of nursing and healthcare. One way to accomplish this is to focus on encouraging nurse educators to include curricular content to empower and nursing students and help them build activism competencies. Friere’s framework (2018) on overcoming oppression provides a model for educators to reimagine their work. More immediately, this would be best done through working to create diverse and inclusive practices, educational content, and research environments that celebrate nuanced dialogue, dissent, and activism.

Social issues need to be included in classroom and in practice discussions.Social issues need to be included in classroom and in practice discussions. In this context difficult racial and socioeconomic conversations can take place to not only address short-term activism but also to think about and build nursing capacity to discuss long-term and systemic activism that is needed beyond the hospital/clinical walls. Nurses should be seen as experts with an important perspective and be empowered to speak up about issues.

Nursing Leadership. Leadership was not discussed within the existing literature but plays an integral role in the development of nurses to lead causes and mobilize change. In the words of Wharton Management Professor Michael Useem (2019), “At the core, leadership entails mobilizing yourself and others to make a difference in the lives of many” (Wharton, 2019, para. 6). We have strong examples of nurse activists as leaders throughout nursing history. An opportunity exists for members of the nursing profession to create a new generation of leaders who are comfortable integrating activist approaches into their leadership roles.

Limitations

Although our review highlighted many aspects of activism within nursing, some limitations warrant mention. By limiting to peer-reviewed articles in the English language, the authors may have missed unpublished papers, dissertations, and theses. Thus, our findings provide a comprehensive, but somewhat selected perspective of activism. Second, there is no standardized definition of activism within the literature, and the term is often discussed or used interchangeably with other concepts such as advocacy, engagement, and social justice. In addition, this review focused on the operationalization of activism and not just discussion about the concept of activism, which may have limited our ability to fully explore the literature on the topic. Third, there was a noted lack of theoretical or conceptual frameworks to advance the concept of activism in the literature.

Conclusion

Despite less overt nursing activism than in the past, there are myriad opportunities for nurses...The nursing profession includes close to 5 million members in the US, (National Council of State Boards of Nursing, 2020). As such, nurses are strongly positioned to have an impact as activists if members of the profession can work collectively to define activism and determine how to best utilize its strengths to pursue a common agenda to promote public well-being. Despite less overt nursing activism than in the past, there are myriad opportunities for nurses to partake in dismantling systemic injustices that permeate American society. Nurses have great potential and power to lead change within healthcare; to do so, they need to reframe their identity from exclusive ties to individual patients and health systems to agents of change for better health of our nation and planet. As the Nursing Now USA initiative (ANA, n.d.) continues to influence national policy centered on education, practice, and employment, this article has responded to the call for evidence and highlighted tangible recommendations to engage and re-engage nurses, educational institutions, and organizations willing and wanting to be safe spaces for nurse activism, in whatever form it takes shape.

Authors

Melissa T Ojemeni, PhD, RN

Email: mojemeni@pih.org

ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1620-9864

Dr. Ojemeni has over 15 years of clinical bedside nursing experience having worked domestically, in East Africa, and Haiti. Her body of work has been focused on nursing leadership, human resources for health capacity building, and global health. She is currently the director of nursing education, research, and professional development at Partners In Health where she works to accompany nursing colleagues in resource limited settings to advance the nursing profession and improve patient care. Dr. Ojemeni holds a PhD from New York University Rory Meyers College of Nursing; a Master of Arts in International Peace and Conflict Resolution with a global health concentration from Arcadia University; and a Bachelor of Science in Nursing degree from Gwynedd Mercy University.

Jin Jun, PhD, RN

Email: jun.128@osu.edu

Dr. Jun is an assistant professor in the Ohio State University College of Nursing. She received a BSN and MSN from the University of Pennsylvania and PhD from New York University. Her area of research centers on the health and wellbeing of clinicians, particularly nurses. She is interested in exploring the intersections of individual, community and systems-level factors to health and well-being and developing interventions using the comprehensive whole-person approach.

Caroline Dorsen, PhD, FNP-BC, FAAN

Email: cd861@sn.rutgers.edu

Dr Dorsen (she/her) is Associate Professor and Associate Dean for Clinical Partnerships at Rutgers University School of Nursing. She is a scholar, educator, and family nurse practitioner whose passion is the intersection of health and social justice. For the past 15 years, her research, teaching and advocacy work has largely focused on the role of stigma and bias in social determinant, LGBTQ+ and substance use disparities. In 2020, Caroline was the recipient of NYU’s MLK, Jr Faculty Award sponsored by the President and Provost for “exemplifying the spirit of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. through teaching excellence, leadership, social justice activism, and community building.” She received the 2021 “Beloved Community” award with colleagues from around Rutgers University. She was inducted as a Fellow in the American Academy of Nursing in 2021.

Lauren Gerchow, MSN, RN

Email: lmg490@nyu.edu

Ms. Gerchow is a doctoral student at the Rory Meyers College of Nursing. Her interest in nurse activism has been shaped by her experiences as a Nurse-Family partnership nurse working with immigrant populations in New York City and San Francisco. Her research currently focuses on issues of shared decision-making in reproductive health. She obtained a Bachelor of Science in Nursing at San Francisco State University and a Master of Science in Nursing from the University of Colorado-Denver.

Gavin Arneson, BSN, RN

Email: ga1179@nyu.edu

Mr. Arneson contributed to this work as an undergraduate nursing student at New York University and is currently a practicing staff nurse in a New York hospital. As a student, he was involved in several social justice activism projects.

Cynthia Orofo, BSN, RN

Email: orofo.c@northeastern.edu

Ms. Orofo is a cardiothoracic ICU nurse in Boston, MA and PhD candidate at Northeastern University School of Nursing. In addition to her cardiac experience, she also functioned as a COVID ICU nurse during the height of the pandemic. Additionally, she has also served vulnerable populations as a community health worker, student nurse and currently operates as a public health nurse on a mobile health van across Massachusetts. Merging the two domains of public health and hospital-based care has been a passion of hers, inspiring her doctoral research interests. As a current PhD candidate, she has contributed to a number of scholarly projects related to health disparities and equitable care delivery. In addition to her clinical and research experiences, she remains a committed advocate for equity, diversity, and inclusion by leading discourse and creating initiatives to address relevant issues and points of action at her institutions.

Adrianna Nava, PhD, MPA, MSN, RN

Email: nava.adrianna@gmail.com

Dr. Nava is an advocate for increasing access to care for underserved populations. She currently serves as the President of the National Association of Hispanic Nurses (NAHN) and is focused on building the leadership capacity of Hispanic nurses who continue to be underrepresented in nursing and healthcare leadership positions across the country. She is currently a Performance Measures Research Scientist at the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) in Washington, DC. Previously, she was in a nursing leadership role as the Chief of Quality at the Edward Hines Jr. VA Hospital in Hines, IL. Dr. Nava has an MPA’20 from Harvard University; a PhD ’19 in Nursing and Health Policy from the University of Massachusetts Boston; an MSN ’12 in Health Leadership and Policy from the University of Pennsylvania; and a BSN ’09 from Saint Francis Medical Center College of Nursing.

Allison P. Squires, PhD, RN, FAAN

Email: aps6@nyu.edu

Dr. Squires is an associate professor and, at the time of this publication, was the director of the Florence S. Downs PhD Program in Nursing Research & Theory Development at NYU Rory Meyers College of Nursing. She was the 2019–2020 Distinguished Nurse Scholar in Residence for the National Academy of Medicine where she worked on the consensus study for the next Future of Nursing 2020–2030 report. An internationally recognized health services researcher, Prof. Squires has led or participated in studies covering 50 countries to date and domestically, her research focuses on improving immigrant and refugee health outcomes with a special interest in breaking down language barriers during the healthcare encounter. Professor Squires completed a PhD at Yale University, MSN at Duquesne University, and BSN at the University of Pennsylvania. She completed a Post-Doctoral Fellowship in Health Outcomes Research at the University of Pennsylvania. In addition to her primary appointment at the College of Nursing, she holds affiliated faculty appointments with the Grossman School of Medicine, Center for Latin American Studies, and the Center for Drug Use and HIV Research at NYU.

References

American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2020, November 5). The essentials: Core competencies for professional nursing education [Unpublished draft].

American Nurses Association. (n.d.). Nightingale Challenge. https://www.nursingworld.org/get-involved/connect/nightingale-challenge/

Amiri, A., & Zhao, S. (2019). Working with an environmental justice community: Nurse observation, assessment, and intervention. Nursing Forum, 54(2), 270-2719. https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12327

Arksey, H., & O'Malley, L. (2005, 2005/02/01). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Black, B. (2014). Professional nursing: Concepts and challenges. Elsevier Saunders.

Boutain, D. (2005). Social justice in nursing: A review of literature. Caring for the vulnerable, 21-29.

Buettner-Schmidt, K., & Lobo, M. L. (2012). Social justice: A concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68(4), 948-958. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05856.x

Busari, J. O., Moll, M. F., & Duits, A. J. (2017). Understanding the impact of interprofessional collaboration on the quality of care: A case report from a small-scale resource limited health care environment. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 10, 227–234. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S140042

Byrd, M. E., Costello, J., Gremel, K., Schwager, J., Blanchette, L., & Malloy, T. E. (2012). Political astuteness of baccalaureate nursing students following an active learning experience in health policy. Public Health Nursing, 29(5), 433-443. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1446.2012.01032.x

Coleman, T. (2020). Anti-racism in nursing education: Recommendations for racial justice praxis. Journal of Nursing Education, 59(11), 642-645. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20201020-08

Des Jardin, K. E. (2001). Political involvement in nursing—education and empowerment. AORN Journal, 74(4), 467-475. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0001-2092(06)61679-7

Dickman, N. E., & Chicas, R. (2021). Nursing is never neutral: Political determinants of health and systemic marginalization. Nursing Inquiry, e12408. https://doi.org/10.1111/nin.12408

Effland, K. J., & Hays, K. (2018). A web-based resource for promoting equity in midwifery education and training: towards meaningful diversity and inclusion. Midwifery, 61, 70-73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2018.02.008

Effland, K. J., Hays, K., Ortiz, F. M., & Blanco, B. A. (2020). Incorporating an equity agenda into health professions education and training to build a more representative workforce. Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health, 65(1), 149-159. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmwh.13070

Florell, M. C. (2021). Concept analysis of nursing activism. Nursing Forum, 56(1), 134-140. https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12502

Forrester, D. A. (2016). Nursing's greatest leaders: A history of activism. Springer Publishing Company.

Fowler, M. D. M. (2021). Guide to the code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements: Development, interpretation, and application (2nd ed.). American Nurses Association.

Freire, P. (2018). Pedagogy of the oppressed: 50th anniversary edition. (Myra Bergman Ramos, Trans.). Bloomsbury Academic.

Gordon, W. M. (2016). A racial equity toolkit for midwifery organizations. Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health, 61(6), 768-772. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmwh.12551

Gordon, W. M., McCarter, S. A., & Myers, S. J. (2016). Incorporating antiracism coursework into a cultural competency curriculum. Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health, 61(6), 721-725. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmwh.12552

Habibzadeh, H., Jasemi, M., & Hosseinzadegan, F. (2021). Social justice in health system; a neglected component of academic nursing education: A qualitative study. BMC nursing, 20(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-021-00534-1

Johnston, D., & Landreneau, K. (2016). Improving health through political activism. Journal of Christian Nursing, 33(4), 225-229. https://doi.org/10.1097/CNJ.0000000000000314

Maldonado, L. (2014). Lessons in community health activism: The maternity care coalition, 1970–1990. Family & Community Health, 37(3), 212-222. https://doi.org/10.1097/FCH.0000000000000030

Matheson, L. K., & Bobay, K. (2007). Validation of oppressed group behaviors in nursing. Journal of Professional Nursing, 23(4), 226–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2007.01.007

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Advocacy. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/advocacy

McSpedon, C. (2020). A conversation with Monica R. McLemore. American Journal of Nursing, 120(9), 68-70. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000697676.06959.19

Morin, K. H., & Baptiste, D. (2020). Nurses as heroes, warriors and political activists. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(15-16), 2733. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15353

Moorley, C., Darbyshire, P., Serrant, L., Mohamed, J., Ali, P., & De Souza, R. (2020). Dismantling structural racism: Nursing must not be caught on the wrong side of history. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(10), 2450–2453. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14469

Morse, J. (2019). Legal mobilization in medicine: Nurses, rape kits, and the emergence of forensic nursing in the United States since the 1970s. Social Science & Medicine, 222, 323-334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.12.032

Moss, E., Sifert, P.C., & O’Sullivan, A. (2016). Registered nurse as interprofessional collaborative partners: Creating value-based outcomes. The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 21(3). https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol21No03Man04

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2020). Number of nurses in U.S. and by jurisdiction. https://www.ncsbn.org/14283.htm

Oxford University Press. (n.d). Activism. In Oxford English Dictionary.

Page, M., McKenzie, J., Boussuyt, P., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T., Mulrow, C., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J., Akl, E., Brennan, S., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M., Li, T., Loder, E., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S…Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Paluzzi, P., Gaffikin, L., & Nanda, J. (2000). The American College of Nurse-Midwives’ domestic violence education project: Evaluation and results. Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health, 45(5), 384-391. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1526-9523(00)00056-8

Pollitt, P. (2018). Nurses fight for the right to vote. The American Journal of Nursing, 118(11), 46–54. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000547639.70037.cd

Poole, J., Borza, J., & Cook, L. (2019). Impact of education on professional involvement for student registered nurse anesthetists' political activism: Does education play a role? AANA Journal, 87(2).

Purpora, C., & Blegen, M. A. (2012). Horizontal violence and the quality and safety of patient care: A conceptual model. Nursing Research and Practice, 2012, 306948. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/306948

Quinn, B. L., El Ghaziri, M., & Knight, M. (2019). Incorporating social justice, community partnerships, and student engagement in community health nursing courses. Teaching and Learning in Nursing, 14(3), 183-185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.teln.2019.02.006

Rains, J. W., & Barton-Kriese, P. (2001). Developing political competence: A comparative study across disciplines. Public Health Nursing, 18(4), 219-224. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1446.2001.00219.x

Rooddenhghan, Z., Yekta, P.Z., & Nasrabadi, N. (2015). Nurses, the oppressed oppressors: A qualitative study. Global Journal of Health Science, 7(5), 239–245. https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v7n5p239

Rudner, N. (2021). Nursing is a health equity and social justice movement. Public Health Nursing, 38(4), 687–691. https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.12905

Settle, P. D. (2014). Nurse Activism in the newborn intensive care unit: Actions in response to an ethical dilemma. Nursing Ethics, 21(2), 198-209. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733012475254

Sucharew, H., & Macaluso, M. (2019). Progress notes: methods for research evidence synthesis: The scoping review approach. Journal of Hospital Medicine, 14(7), 416-418. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3248

Terry, L., & Bowman, K. (2020). Outrage and the emotional labour associated with environmental activism among nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(3), 867-877. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14282

VandeWaa, E. A., Turnipseed, D. L., & Lawrence, S. (2019). A leadership opportunity: Nurses' political astuteness and participation. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, 49(12), 628-630. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000000827

Wall, B. M. (2009). Catholic nursing sisters and brothers and racial justice in mid-20th-century America. Advances in Nursing Science, 32(2), E81. https://doi.org/10.1097/ANS.0b013e3181a3d741

Watson, J. (2020). Nursing's global covenant with humanity–unitary caring science as sacred activism. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(2). https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13934

Weitzel, J., Luebke, J., Wesp, L., Graf, M. D. C., Ruiz, A., Dressel, A., & Mkandawire-Valhmu, L. (2020). The role of nurses as allies against racism and discrimination: An analysis of key resistance movements of our time. Advances in Nursing Science, 43(2), 102-113. https://doi.org/10.1097/ANS.0000000000000290

Wharton University of Pennsylvania. (2019, November, 6). Embracing leadership in an era of activism. https://kwhs.wharton.upenn.edu/2019/11/embracing-leadership-era-activism/

World Health Organization. (n.d.). Nursing Now. https://www.nursingnow.org

Zauderer, C. R., Ballestas, H. C., Cardoza, M. P., Hood, P., & Neville, S. M. (2008). United we stand: Preparing nursing students for political activism. The Journal of the New York State Nurses' Association, 39(2), 4-7.

Ziehm, S. R., Karshmer, J. F., Greiner, P. A., Greenberg, C. S., Berman, A., & McFarland, P. (2019). Statewide political activism for California academic nursing leaders. Journal of Professional Nursing, 35(1), 32-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2018.01.001

Zuzelo, P. R. (2020). Ally, advocate, activist, and adversary: Rocking the status quo. Holistic Nursing Practice, 34(3), 190-192. https://doi.org/10.1097/HNP.0000000000000389