Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) programs mediate the physical and emotional impact of cardiac events. Women are less likely to be referred to and complete CR programs than men resulting in poorer cardiac outcomes. Methods: This qualitative descriptive study examined women’s reasons and barriers for attending and completing a CR program. Findings suggest women choose to complete CR programs based on their experiences while attending the program. Discussions of strategies for enrolling women and maximizing their experiences are identified as well as areas of future research for improving women’s experiences of cardiac rehabilitation.

Key Words: Cardiac rehabilitation, women, MI, qualitative research, cardiac interventions

Women are less likely to be referred to and complete CR programs than men resulting in poorer cardiac outcomes.Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) programs, especially Phase II (outpatient), mediate the physical and emotional impact of a cardiac event (Anderson et al., 2016; Balady et al., 2011; Colbert et al., 2015; McMahon, Ades, & Thompson, 2017). Researchers have shown that the physical activity associated with CR programs decreases C-reactive protein (inflammation) and improves endothelial function (atherosclerosis) (Sadeghi et al., 2018), both of which reduce thrombus formation. CR programs also improve physical stamina and emotional health, but studies show it is underutilized among the women and elderly populations (Colbert et al., 2015; Reed et al., 2018;Valencia, Savage, & Ades, 2011). While numerous studies have identified barriers to CR attendance (Supervia et al., 2017; Resurreccion, Motrico, Rubio-Valera, Mora-Pardo, & Moreno-Peral, 2018), to our knowledge no studies have explored factors that facilitate CR completion among women. Understanding what motivates women to complete CR will provide information that can direct practice and improve CR completion by women.

CR programs also improve physical stamina and emotional health, but studies show it is underutilized among the women and elderly populationsTo determine the state of the science we reviewed the literature and identified factors that enhanced or limited CR attendance by women. One factor associated with limited attendance is related to low referral rates. Referral rates are highest in industrialized countries, as many middle and low-income countries do not have access to CR programs (Turk-Awadi, Sarrafzadegan, & Grace, 2014). However, Aragam et al. (2011) still found referral rates in the US and Canada to be less than 30% and similar findings were reported worldwide by Turk-Awadi and others (Turk-Awadi et al., 2014). Thus, even in high-income countries where CR is available and a healthy referral process is in place CR attendance remains low, especially among women (Balady et al., 2011).

Barriers to CR attendance in countries where CR was available were identified in the literature but were not always specific to women. Barriers included personal beliefs about the efficacy of diet and exercise; conflicting priorities such as home responsibilities, and practical issues such as a lack of time, resources or transportation (Supervia et al., 2017; Resurreccion et al., 2018). Studies that tested interventions directed at CR attendance barriers reported some success; however, the majority studied both men and women (Supervia et al., 2017). Studies of women-only or women-specific CR programs reported conflicting results. Grace and others in a large multi-arm randomized controlled clinical trial found no significant difference in adherence or CR attendance between women attending women-specific CR programs and other CR programs (Grace et al., 2016). However Beckie and Beckstead (2010) found that gender specific group interventions improved attendance by four sessions compared to traditional mixed programs, but gender specific group membership only accounted for 5% of the variance in attendance between groups. In recent work, an all-woman yoga-based CR resulted in significantly higher continuation and completion compared to mixed-sex CR (95% vs. 56% and 72% vs. 12%, respectively) (Murphy et al., 2021).

Barriers included personal beliefs about the efficacy of diet and exercise; conflicting priorities such as home responsibilities, and practical issues such as a lack of time, resources or transportation There are numerous reports of barriers to overall CR attendance (Supervia et al., 2017; Resurreccion et al., 2018), however no one has studied women who completed CR and identified factors that facilitated their completion. A greater understanding of these experiences can inform future research and lead to innovative approaches to improving the health of this population. Thus the purpose of this study was to address this gap and develop a theoretical understanding of the decision-making processes involved in CR completion by women. A qualitative descriptive design using semi-structured interviews was used to develop an understanding of the factors that impact women’s CR attendance and completion decisions.

Methods

Sample and Setting

The setting for this study was a Phase II CR center within a quaternary care center in the Midwest. The outpatient Phase II CR center currently has over 4,000 patient visits per year. We used purposeful sampling methods as described by Glaser and Strauss (1967) to recruit women who had attended CR at a single study site, and had completed at least 25 out of 36 sessions (considered Phase II completion) of CR, spoke English, and were able to participate in an in-person interview. Sampling continued until data saturation was reached (three consecutive interviews yielding no new information), resulting in a sample size of 12 informants.

Recruitment

Study informants were identified from an electronic database listing of all patients referred to CR at the hospital. One of the investigators contacted potential study informants (women who had completed at least 25 out of 36 sessions of CR), provided information about the study and gave an opportunity to ask questions. Those interested in participating in the study were scheduled for a one-on-one interview at a time of their preference.

Data Collection

The interviews were conducted by all three investigators (LAS, CNB, and SLS). The first author (LAS), is a nurse scientist with a PhD in exercise physiology. The second author (CNB), is a nurse scientist with a PhD in adult and organization development with extensive interviewing experience. Finally, we had a senior nurse scientist (SLS) with a PhD in nursing and previous experience conducting and publishing qualitative research. She oversaw the interview, review, and analysis process.

Investigators conducted and digitally recorded the interviews in a private area at the CR site or via phone, per study informant’s preference between June, 2018 and March, 2019. The interview began with several demographic questions. We asked all study informants the same series of Grand Tour open-ended questions (Table 1) and the interviewers followed the same semi-structured script to prevent variation due to different interviewing skills. The length of interviews ranged from 8 to 20 minutes.

Table 1. Grand Tour Questions

|

Tell me about your decision to enroll in cardiac rehabilitation. |

|

Tell me what motivates you to come to cardiac rehabilitation. |

|

Tell me about the things or people that have made it possible for you to come to cardiac rehabilitation. |

Ethical Considerations

Study approval was obtained from the hospital’s Institutional Review Board and procedures in this study were conducted in accordance with the Institutional Review Board approved protocols. Data, including digital recordings of interviews, were stored on the principal investigator’s encrypted computer in a password protected file; and only the three investigators had access to the data or recording.

Data Analysis

Using an iterative process, data collection and analysis occurred simultaneously and took place over the course of one year (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Thematic analysis included six phases as described by Braun and Clarke (2006). First, we transcribed interviews verbatim from the recordings. Transcripts were then read by all investigators while listening to the recordings. Second, codes were created from the data. This process included reviewing new data and comparing it to data previously collected. Next, concepts with similar meaning and contexts surfaced (theme development) and the beginning of a thematic map was created. Fourth, we used constant comparison to determine whether new data fit with the developing themes. Fifth, themes were refined, and lastly a final thematic map was generated in order to describe the perspectives of women who attended CR and the experiences that ultimately led to completion.

Thematic analysis included six phases as described by Braun and ClarkeReliability and validity of a qualitative study is assessed through confirmability, dependability, credibility, and transferability (Sikolia, Biros, Mason, & Weiser, 2013). Confirmability was assured through the constant comparative process. The team listened to recorded data, read and re-read transcripts, and kept careful notes of discussions to confirm objectivity. To assure dependability, three investigators explored the data independently and then as a group. Storage and organization of data allowed investigators to easily return to recordings or transcriptions to compare old data with new data. To assure credibility, the research team strived to remain unbiased through the consistent use of grand tour questions and a script. Finally, transferability was enhanced through purposeful sampling and our detailed account of the research and analysis.

Findings

More than half of the sample (N = 12) was White (n = 8; 67%) and between the ages of 47 and 86 years (70, ± 11). Additional demographic data is presented in Table 2. In order to protect the study informants’ identities, pseudonyms are used in place of actual names.

Table 2. Demographic characteristics

|

Study Informants |

Age |

Diagnosis |

Race/ Ethnicity |

Education |

Income |

|

|

(pseudonyms) |

|

|

|

|

(thousands /year) |

|

|

N = 12 |

Teresa Marie Bernice Shirley Janet Rebecca Olivia Margie Annette Leah Clair Allison |

74 65 82 69 74 75 86 64 60 80 62 47 |

CAD/CABG HF PAD HF MI SCAD MI CAD/PCI/PAD Fibroelastoma CAD/PCI SCAD MI |

Black White White Black Hispanic White White White White Indian White White |

HS >HS >HS >HS HS >HS >HS >HS >HS >HS >HS >HS |

<50 50-100 <50 <50 <50 >100 50-100 <50 50-100 50-100 50-100 50-100 |

HS = High School; MI = Myocardial Infarction; CAD = Coronary Artery Disease; PAD = Peripheral artery disease; SCAD = Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection; Fibroelastoma = a rare benign cardiac tumor

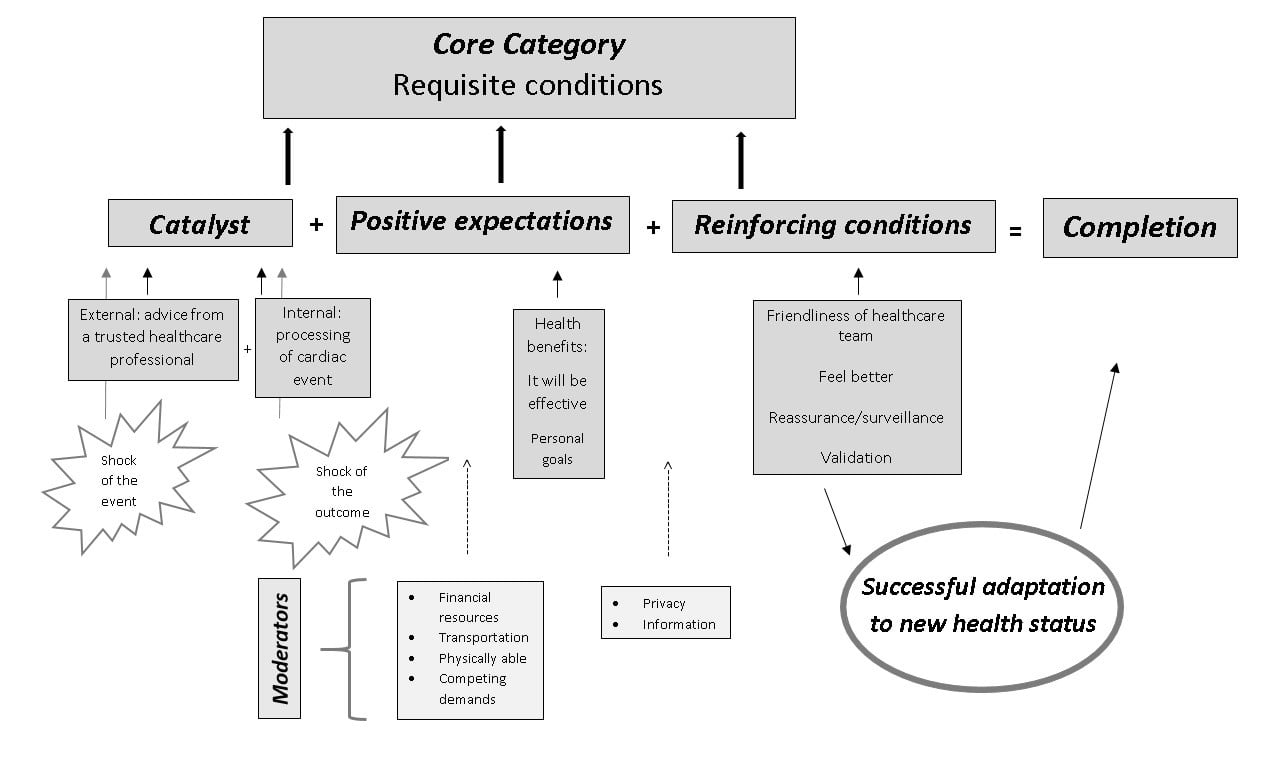

The requisite conditions include catalyst, positive expectations of CR, and reinforcing conditions that interact and lead to decisions to complete CR. A thematic map was developed (Figure 1) which identifies three requisite conditions (core categories) that have an additive impact on CR completion. The requisite conditions include catalyst, positive expectations of CR, and reinforcing conditions that interact and lead to decisions to complete CR. We identified the factor that precipitated CR enrollment as a catalyst. A catalyst needs to exist if women are to begin thinking about attending CR. A catalyst would include recommendations by a healthcare provider (external catalyst) after the patient experienced a cardiac event. A typical response was expressed by one woman (Margie) as “My doctors, surgeons…told me it would be beneficial.” Another typical catalyst was shock of the cardiac event (internal catalyst). Women were actually surprised by the cardiac event and had previously not realized that they were really at risk, until it happened to them. Some comments that attested to this “shock” included the following responses.

Allison: “I do NOT want to have another heart attack.”

Rebecca: “I always knew that heart attacks were different for women. I mean, I thought I had the flu.”

Clair: “I thought I had the stomach flu and they told me I was having a heart attack and I was like… Oh my gosh!”

Marie: “I don’t know what I did. I always exercised and I always tried to eat right, I always tried to take care of myself and then BOOM, I get this.”

Expectations

While a precipitating event (Catalyst) may result in enrollment in a Phase II CR program, according to the literature it is insufficient to sustain attendance and completion of a CR programWhile a precipitating event (Catalyst) may result in enrollment in a Phase II CR program, according to the literature it is insufficient to sustain attendance and completion of a CR program (Balady et al., 2011). The women interviewed in this study shared that they had positive expectations of the CR program. That is, they felt that CR would make a difference in their life and health. Without positive expectations it might have been difficult to complete CR. Women in our study explained their expectations in positive terms. Comments included:

Shirley: “My health. I want to live as long as I can for my grandkids.”

Shirley: “It’s good for my health and my well-being.”

Janet: “To lose the weight and live longer…to live to my mother’s ripe old age.”

Annette: “I had lost a lot of strength…I felt it would be very beneficial for me to come to CR and do an exercise program that I normally wouldn’t do on my own and build that strength up.”

Reinforcers

While a catalyst and positive expectations about CR were essential to enrollment and beginning a Phase II CR program, the ability to complete 25 sessions or more was predicated on reinforcing conditions. Conditions that provided motivation for women to complete the CR program had to do with those things that made the experience pleasant and effective. Pleasantness of the experience was chiefly related to CR personnel, while effectiveness seems to be evaluated in light of how they felt during and after CR sessions.

The most common reinforcing condition was related to the CR staff, especially the nurses, and how the staff made them feel. The most common reinforcing condition was related to the CR staff, especially the nurses, and how the staff made them feel. The informants spoke of the CR staff as if they had become friends, they felt the staff really cared about them, they were friendly and helpful. The female informants provided accounts of reassurance, surveillance, and validation of the efforts. Some examples of reassurance comments included:

Olivia: “One therapist, an RN…she notices if my nose runs and I need a tissue. She moves constantly and she is terrific.”

Teresa: “The nurses and everything … it was amazing how they treat me so nice”

Marie: “The staff is amazing. They don’t want you to overdo…”

The informants felt reassured that the staff was monitoring them and protecting them as they proceeded through the CR classes. This is seen in the following comments:

Teresa: “When I get here they take care of me. They keep checking my pressure and I love them for that.”

Leah: “The nurses are very kind.”

Bernice: “My feet always hurt, but they are very encouraging here. I feel watched over here.”

Clair: “Being watched I feel more safe and secure. I was scared at first. I had a SCAD [spontaneous coronary artery dissection] and I worried it would rupture. I feel safe. They watch me. They tell me if my heart rate is too high or too low. It helps me with planning my exercise at home.

The informants related that the outcomes they experienced exceeded their expectations and this in itself motivated them to continue to completion. Comments included:

Teresa: “I feel better. I feel ok when I come but when I leave I feel much better. I am tired but I breathe better and am more energetic.”

Teresa: “When I come here I feel relief…like I had a good workout”

Annette: “And the more I came, the more I enjoyed it. I felt my stamina being built back up and I saw progress. If I hadn’t seen progress it might have been different. But noticing the progress I thought YES, keep this up.”

Clair: “The more I stick with my cardiac rehab the more I can tolerate and that’s a good thing for me.”

Additional Findings

Barriers did not strongly influence whether the women completed CR...Barriers did not strongly influence whether the women completed CR, although mentioned by the informants and acknowledged by the investigators. The women discussed how they continued to attend despite barriers. These barriers included financial resources, physical ability, transportation, and privacy. Thus it would seem for this group of women, barriers while acknowledged, did not affect their desire to complete CR.

Figure 1. Thematic Map

Discussion

The findings of this study provide novel insight into the common themes surrounding the experiences that led to CR completion among women. For the women in this study, enrollment in CR was impacted by both internal and external catalysts and their expectations of CR. However, the factors that kept them coming and resulted in completion of the Phase II CR program had more to do with the CR experience; reinforcing conditions that motivated them to come in spite of potential barriers. In this way our findings are unique, in that the primary focus of previous studies has been to identify factors that inhibit attendance (Resurreccion et al., 2018; Supervia et al., 2017). Our research shows that the women who completed CR had very different perspectives from those who identified reasons for dropping out of CR, primarily that the experience was more important to them than the barriers.

Researchers have identified that a catalyst such as automatic referral to CR is one factor necessary for attendance. Women are not referred to CR at the same rate as men (Balady et al., 2011; Colbert et al., 2015); however, in facilities such as the study site, automatic referral for all qualifying patients has become the norm. Additionally, referral does not always translate into the utilization and completion of CR, especially by women (Martin et al., 2012; Pio, Chaves, Davies, Taylor, & Grace, 2019). Like our study, researchers found that an external catalyst (such as a doctor’s recommendation) was a requisite condition for beginning CR (Schopfer et al., 2016; Khadanga, Gaalema, Savage, & Ades, 2021); and like Jokar, Yousefi, & Yousefy (2017), our study found the shock of the precipitating event (internal catalyst) was also associated with beginning CR.

Our work is consistent with previous literature regarding women’s beliefs and expectations that the program would work (Neubeck et al., 2012; Sutantri, Cuthill, & Holloway, 2019). Our thematic map illustrates that perceived effectiveness of the CR program is one of the most important expectations that women have when entering a CR program. When a life threatening event is present, belief in the effectiveness of CR (positive expectation) is critical to the decision to begin Phase II CR. By supporting and reinforcing goals and expectations, nurses and other staff can help to increase the likelihood of CR completion among women.

The informants in our study expressed that it was rewarding to see results from the exercise. In previous qualitative work women revealed that they dropped out of CR when they perceived the experience as more negative and as having little benefit, in part due to the fact their expectations were not fulfilled (Resurreccion et al., 2018). Previous research identified barriers such as time and transportation (Supervia et al., 2017); however, although acknowledged as bothersome, neither time nor transportation impacted CR completion in our sample. Friendliness and caring behaviors of the nurses and other staff was the most frequently mentioned reinforcing condition for women in this study. This is consistent with findings reported by Schopfer et al. (2016). However, Schopfer and others (2016) did not report data specific to women. Thus, nurses and other members of the care team should engage in behaviors that offer assurance and help women to feel safe and well in the CR setting. Women may perceive these caring behaviors as an important part of the CR experience, ultimately leading to CR completion.

Strengths and Limitations

The major strength of this study was our approach to understanding the experiences leading to completion of a Phase II CR program rather than concentrating on factors that prevented women from enrolling and completing CR. The biggest limitation is the use of a single U.S. site for recruitment. However, our sample contained women from a variety of socio-economic and ethnic backgrounds, thus our findings may be transferable to similar populations.

Conclusion

Understanding the experiences of women who complete CR is vital to successful interventions.Understanding the experiences of women who complete CR is vital to successful interventions. We found no evidence in the data to suggest that any part of the thematic map can be bypassed if women are to complete CR. While maintaining an appreciation for the importance of removing barriers to CR completion, future research should focus on supporting those beliefs and activities that reinforce ongoing attendance and completion. Conditions associated with completion of CR include referring women to CR, assessing personal goals and individual CR expectations, treating patients with friendliness and offering support and reassurance, and validating their progress. Further, CR staff can reinforce attendance and completion by assuring women feel well and safe. Future research should determine the effect and effectiveness of these recommendations.

Authors

Lee Anne Siegmund, PhD, RN, ACSM-CEP

Email: siegmul@ccf.org

Dr. Siegmund is a Nurse Scientist II in Cleveland Clinic’s Office of Nursing Research and Innovation. Dr. Siegmund has an ongoing desire to improve clinical practice in order to prevent disease and complications that may result from non-optimized behaviors. Her research interests include cardiac rehabilitation, and physical activity to improve outcomes among older adults. Most recently, Dr. Siegmund has completed work on physical activity and COVID-19 disease severity, and published research on reduced physical activity and social isolation as predictors of depression among older adults during COVID-19.

Christian N. Burchill, PhD, MSN, RN, CEN

Email: christian.burchill@pennmedicine.upenn.edu

Dr. Burchill was Nurse Scientist II, Office of Nursing Research and Innovation, Cleveland Clinic and is now Director of Nursing Research and Science, Penn Medicine Lancaster General Hospital. He is a lifetime member of the Emergency Nurses Association and a member of the ENA Emergency Nurses Research Advisory Council. His work with the American Nurses Association includes serving on steering committees for the End Nurse Abuse Campaign and the Workplace Violence Position Statement. Dr. Burchill’s research interest focus on understanding how nurses’ non-cognitive attributes affect professional growth and development as well as the delivery of nursing care.

Sandra L. Siedlecki, PhD, RN, APRN-CNS, FAAN

Email: SIEDLES@ccf.org

Dr. Siedlicki is a Senior Nurse Scientist in Cleveland Clinic’s Office of Nursing Research and Innovation. Dr. Siedlecki serves as a research mentor to students, clinical nurses, and APRNs interested in investigating phenomena that will enhance nursing practice and improve patient outcomes. Dr. Siedlecki maintains her own program of research exploring the effects and effectiveness of non-pharmacologic interventions to improve health and wellness. Dr. Siedlecki has an extensive record of publications and presentations, and serves as research editor of the Journal of Clinical Nurse Specialist.

References

Anderson, L., Oldridge, N., Thompson, D.R., Zwisler, A., Rees, K., Martin, N., & Taylor, R. (2016). Exercise based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 67(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.044

Aragam, K. G., Moscucci, M., Smith, D.E., Riba, A. L., Zainea, M., Chambers, F. L., Share, D., & Gurm, H. S. (2011). Trends and disparities in referral to cardiac rehabilitation after percutaneous coronary intervention. American Heart Journal, 161(3), 544-551.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2010.11.016

Balady, G. J., Ades, P. A., Bittner, V. A., Franklin, B. A., Gordon, N. F., Thomas, R. J., Tomaselli, G. F., & Yancy, C. W. (2011). American Heart Association Science Advisory and Coordinating Committee. Referral, enrollment, and delivery of cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention programs at clinical centers and beyond: A presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 124(25), 2951-2960. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823b21e2

Beckie, T. M. & Beckstead, J. W. (2010). Predicting cardiac rehabilitation attendance in a generalized randomized clinical trial. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention, 30(3), 147-156. https://doi.org/10.1097/HCR.0b013e3181d0c2ce

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Colbert, J. D., Martin, B. J., Haykowsky, M. J., Hauer, T. L., Austford, L. D., Arena, R. A., Knudtson, M. L., Meldrum, D. A., Aggarwal, S. G., & Stone, J. A. (2015). Cardiac rehabilitation referral, attendance and mortality in women. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, 22(8), 979–986. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F2047487314545279

Glaser, B.G. & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Aldine.

Grace, S. L., Midence, L., Oh, P., Brister, S., Chessex, C., Stewart, D. E., & Arthur, H. M. (2015). Cardiac rehabilitation program adherence and functional capacity among women: A randomized controlled trial. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 91(2), 140-148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.10.021

Jokar, F., Yousefi, H., Yousefy, A., & Sadeghi, M. (2017). Begin again and continue with life: A qualitative study on the experiences of cardiac rehabilitation patients. Journal of Nursing Research, 25(5), 344-352. https://doi.org/10.1097/JNR.0000000000000220

Khadanga, S., Gaalema, D. E., Savage, P., & Ades, P. A. (2021). Underutilization of cardiac rehabilitation in women: Barriers and Solutions. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention, 41(4), 207–213. https://doi.org/10.1097/HCR.0000000000000629

Martin, B. J., Hauer, T., Arena, R., Austford, L. D., Galbraith, P. D., Lewin, A. M., Knudtson, M. L., Ghali, W. A., Stone, J. A., & Aggarwal, S. G. (2012). Cardiac rehabilitation attendance and outcomes in coronary artery disease patients. Circulation, 126(6), 677-687. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.066738

McMahon, S. R., Ades, P. A., & Thompson, P. D. (2017). The role of cardiac rehabilitation in patients with heart disease. Trends Cardiovascular Medicine, 27(6), 420-425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcm.2017.02.005

Murphy, B. M., Zaman, S., Tucker, K., Alvarenga, M., Morrison-Jack, J., Higgins, R., Le Grande, M., Nasis, A., & Jackson, A. C. (2021). Enhancing the appeal of cardiac rehabilitation for women: development and pilot testing of a women-only yoga cardiac rehabilitation programme. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 20(7), 633-640. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjcn/zvab008

Neubeck, L., Freedman, S. B., Clark, A. M., Briffa, T., Bauman, A., & Redfern, J. (2012). Participating in cardiac rehabilitation: A systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative data. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, 19(3), 494-503. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1741826711409326

Pio, C. S. A., Chaves, G., Davies, P., Taylor, R., & Grace, S. (2019). Interventions to promote patient utilization of cardiac rehabilitation: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 8(2), 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8020189

Reed, J. L., Clarke, A. E., Faraz, A. M., Birnie, D. H., Tulloch, H. E., Reid, R. D., & Pipe, A. L. (2018). The impact of cardiac rehabilitation on mental and physical health in patients with atrial fibrillation: A matched case-control study. Canadian Journal of Cardiology, 34(11), 1512-1521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2018.08.035

Resurreccion, D. M., Motrico, E., Rubio-Valera, M., Mora-Pardo, J. A., & Moreno-Peral, P. (2018). Reasons for dropout from cardiac rehabilitation programs in women: A qualitative study. PloS One, 13(7), e0200636. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0200636

Sadeghi, M., Khosravi-Broujeni, H., Salehi-Abarghouei, A., Heidari, R., Masoumi, G., & Roohafza, H. (2018). Effect of cardiac rehabilitation on inflammation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. ARYA Atherosclerosis, 14(2), 85–94. https://doi.org/10.22122/arya.v14i2.1489

Schopfer, D. W., Priano, S., Alsup, K., Helfrich, C. D., Ho, P. M., Rumsfeld, J. S., Forman, D. E., & Whooley, M. A. (2016). Factors associated with utilization of cardiac rehabilitation among patients with ischemic heart disease in the Veterans Health Administration: A qualitative study. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention, 36(3), 167-173. https://doi.org/10.1097/HCR.0000000000000166

Sikolia, D., Biros, D., Mason, M., & Weiser, M. (2013). Trustworthiness of grounded theory methodology research in information systems. Midwest Association of Information Sciences 2013 Proceedings, 16.

Supervia, M., Medina-Inojosa, J.R., Yeung, C., Lopez-Jimenex, F., Squires, R.W., Perez-Terzic, C., Brewer, L.C., Leth, S.E., & Thomas, R.J. (2017). Cardiac rehabilitation for women: A systematic review of barriers and solutions. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 92(4), 565-577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.01.002

Sutantri, S., Cuthill, F., & Holloway, A. (2019). A bridge to normal: A qualitative study of Indonesian women's attendance in a phase two cardiac rehabilitation programme. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 18(8), 744-752. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474515119864208

Turk-Awadi, K., Sarrafzadegan, N., & Grace, S. L. (2014). Global availability of cardiac rehabilitation. Nature Reviews Cardiology, 11(10), 586-596. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrcardio.2014.98

Valencia, H. E., Savage, P. D., & Ades, P. A. (2011). Cardiac rehabilitation participation in underserved populations. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation, 31(4), 203–210. https://doi.org/10.1097/HCR.0b013e318220a7