The concept of nurse engagement is often used to describe nurses’ commitment to and satisfaction with their jobs. In reality, these are just two facets of engagement. Additional considerations include nurses’ level of commitment to the organization that employs them, and their commitment to the nursing profession itself. Because nurse engagement correlates directly with critical safety, quality, and patient experience outcomes, understanding the current state of nurse engagement and its drivers must be a strategic imperative. This article will discuss the current state of nurse engagement, including variables that impact engagement. We also briefly describe the potential impact of compassion fatigue and burnout, and ways to offer compassionate connected care for the caregiver. Such insight is integral to the profession's sustainability under the weight of demographic, economic, and technological pressures being felt across the industry, and is also fundamental to the success of strategies to improve healthcare delivery outcomes across the continuum of care.

Key Words: Patient experience, Press Ganey, framework of suffering, nurse engagement, Compassionate Connected Care, compassion fatigue, burnout

During the 2015 Miss America pageant, Miss Colorado, Kelley Johnson, RN, delivered a heartfelt monologue, titled “Just a Nurse,” in which she shared the story of one of her most memorable patients, an older gentleman with Alzheimer’s disease (NJ.com, 2015). The monologue quickly went viral on social media sites such as Facebook and Twitter. Although it was applauded by many, Johnson’s decision to describe nursing as her talent was mocked by hosts of the daytime television talk show, The View (France, 2015). This move inspired nurses nationwide to further band together on social media to educate the public about the nursing profession (Bryan, 2015).

With urgency and passion, nurses found their collective voice and they used it to speak about nursing education, professionalism, and accountability. With urgency and passion, nurses found their collective voice and they used it to speak about nursing education, professionalism, and accountability. They were united in advocating for their rightful recognition as trusted, valuable members of the healthcare team. And they were engaged—a state of mind that is essential not only to personal and professional fulfillment, but also to organizational success in today’s complex healthcare environment. This demonstrates an alignment that both enchants nurses by bringing purpose to what nurses do and enfranchises nurses by the feeling of belonging both to the profession and to the organization with and for whom they work.

The concept of nurse engagement is often used to describe nurses’ commitment to and satisfaction with their jobs. In reality, these are just two facets of engagement. Additional considerations include nurses’ level of commitment to the organization that employs them, and their commitment to the nursing profession itself.

The concept of nurse engagement is often used to describe nurses’ commitment to and satisfaction with their jobs. Because nurse engagement correlates directly with critical safety, quality and patient experience outcomes (Day, 2014; Laschinger & Leiter, 2006; Nishioka, Coe, Hanita, & Moscato, 2014; Press Ganey, 2013) understanding the current state of nurse engagement and its drivers must be a strategic imperative. This article will discuss the current state of nurse engagement, including variables that impact engagement. We also briefly describe the potential impact of compassion fatigue and burnout and ways to offer compassionate, connected care for the caregiver. Such insight is integral to the profession's sustainability under the weight of the demographic, economic and technological pressures being felt across the industry, and is also fundamental to the success of strategies to improve healthcare delivery outcomes across the continuum of care.

Current State of Nurse Engagement Measurements by Press Ganey

Press Ganey is a provider of patient experience measurement, performance analytics, and strategic advisory solutions for healthcare organizations. Press Ganey measures nurse engagement through proprietary survey instruments designed to assess multiple facets of the nurse experience, including nurse engagement, nurse job satisfaction, and the nurse work environment. This includes the Press Ganey National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators® (NDNQI®) measuring nurse satisfaction, practice environment, and nurse sensitive measures.

...fifteen of every 100 nurses are considered disengaged... Based on performance of nurse employees at one standard deviation (SD) below the mean using the Press Ganey employee engagement database, fifteen of every 100 nurses are considered disengaged (thus lacking commitment and/or satisfaction with their work). Conservative estimates suggest that each disengaged nurse costs an organization $22,200 in lost revenue as a result of lack of productivity (Schaufenbuel, 2013). For a hospital with 100 nurses, that equates to $333, 000 per year in lost productivity. For a large system with 15, 000 nurses, the potential loss skyrockets to $50 million.

This lack of productivity may come in many forms, including complaining to others; failure to offer assistance; performing work with a less-than-optimal attitude; calling in sick; taking longer to complete routine tasks; and failing to go above and beyond when needed. For units with a low level of engagement, it is our opinion that what appear to be staffing issues could be attributed to engagement issues.

In addition to lost productivity, nurse disengagement influences nurse retention... In addition to lost productivity, nurse disengagement influences nurse retention (Sawatzky & Enns, 2012), an important national issue. The average turnover rate for nurses in 2014 was 16.4%, according to the 2015 National Healthcare Retention & RN Staffing Report (NSI Nursing Solutions, 2015). The average cost of turnover for a bedside registered nurse (RN) ranged from $36,900 to $57,300, leading to a loss of $4.9M to $7.6M for an average hospital, according to the survey. This means nursing turnover costs United States hospitals billions of dollars each year.

Available nurse engagement data paint a complex picture. Below we will discuss some of the data with specific impact to nurse engagement in greater detail.

Impact of Tenure and Level of Care

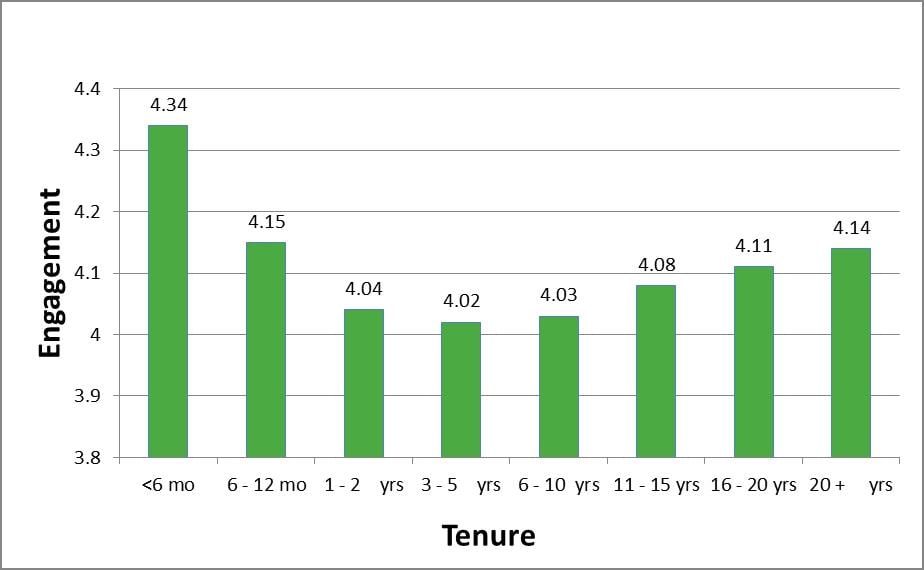

The average engagement of RNs on a 0 to 5 point scale is 4.11 in the Press Ganey database (Dempsey, Reilly, & Noble, 2015). However, the data also indicate that the most engaged nurses are those who have been with the organization less than six months (Figure 1). This may be due to the “honeymoon effect” widely cited in employee research or it may be related to more significant issues of employee empowerment, work design, or leadership (Meyer, 2013).

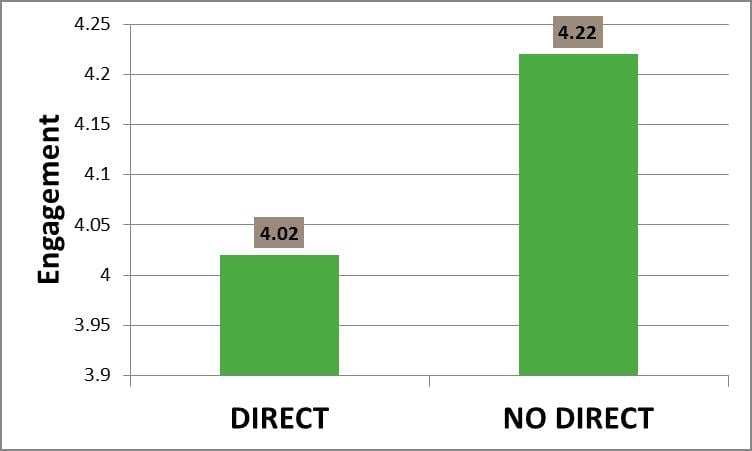

...those nurses providing direct patient care are among the least engaged. To further complicate this engagement dilemma, Press Ganey (2013) data on nurse engagement suggests that, in fact, the further the nurse works from the bedside, the more engaged the nurse (Figure 2). In other words, those nurses providing direct patient care are among the least engaged. Considering the emphasis on patient centered care, and the known relationship between patient experience and engagement (Press Ganey, 2013), this is indeed troubling.

Figure 1. Nurse Engagement Based on Tenure in a Position (Dempsey et al., 2015)

F(1, 7) = 160.21,p= .000

Figure 2. Nurse Engagement Based on Direct/Indirect Provision of Care (Dempsey et al., 2015)

t(37,205) = -9.38,p= .000

Differences in Drivers of Nurse Engagement

An analysis of Press Ganey’s national nurse engagement database (Dempsey et al., 2015) also identified drivers of nurse engagement. Items were selected in decreasing order of beta (standardized regression coefficient) from the pool of items with 66% response rate or higher. The key drivers of nurse engagement in 2015 included:

- This organization provides high-quality care and service.

- This organization treats employees with respect.

- I like the work I do.

- The environment at this organization makes employees in my work unit want to go above and beyond what’s expected of them.

- My pay is fair compared to other healthcare employers in this area.

- My job makes good use of my skills and abilities.

- I get the tools and resources I need to provide the best care/service for our clients/patients.

- This organization provides career development opportunities.

- This organization conducts business in an ethical manner.

- Patient safety is a priority in this organization.

These key drivers offer insight into the most critical factors that influence engagement. As a group, they represent the types of items that have the greatest impact on overall engagement at a national level. Individually, each item tells a piece of the engagement story. It is important to acknowledge that these drivers are based on a national population with a sample size of close to 200,000 nurses (Dempsey et al., 2015). They are not a substitute for local level analysis.

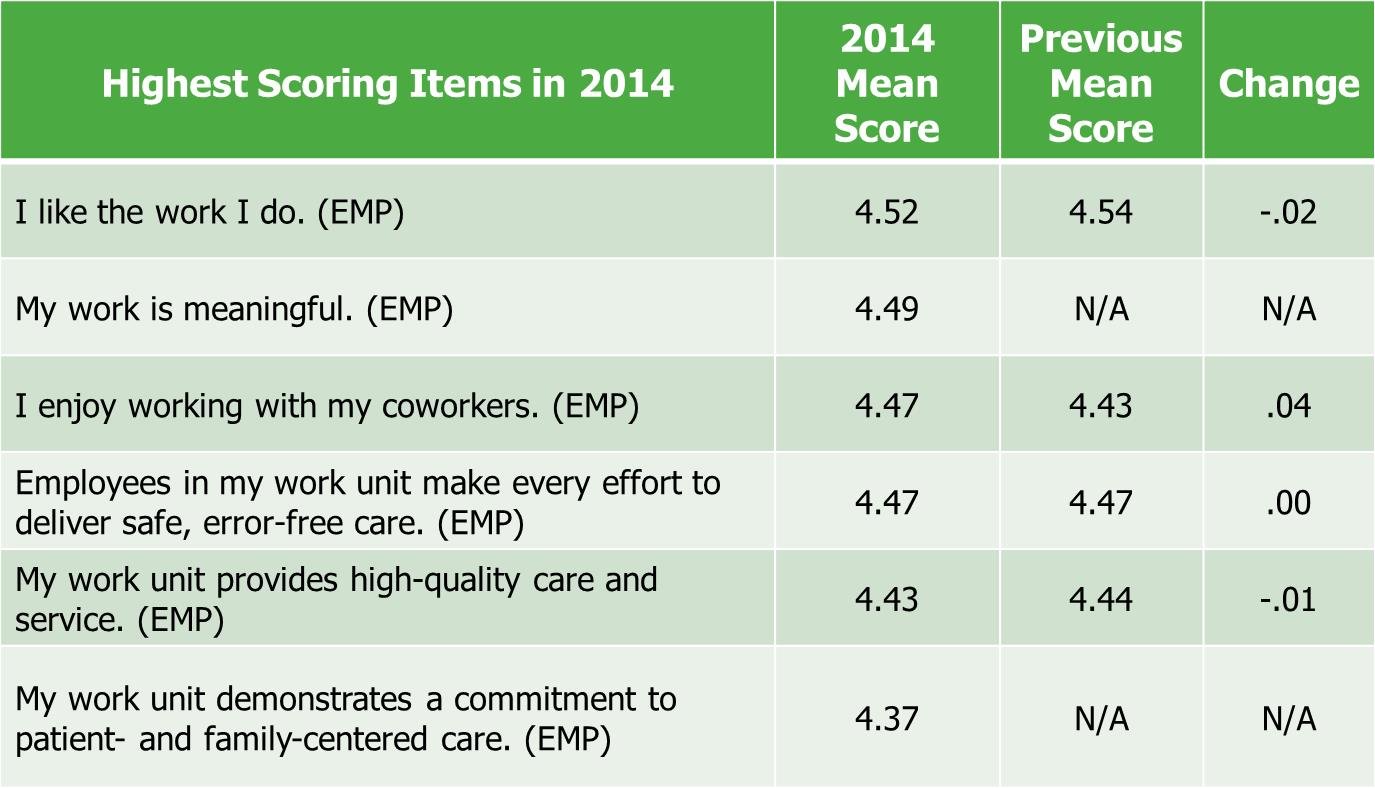

Based on the analysis, the highest-scoring items for nurses included: I like the work I do; my work is meaningful; I enjoy working with my coworkers; Employees in my work unit make every effort to deliver safe, error-free care; My work unit provides high-quality care and service; My work unit demonstrates a commitment to patient and family-centered care (Figure 3). Note that all of these high-scoring items reflect nurses’ feelings about the work itself (enjoyable and meaningful) or the teamwork and effectiveness of the work unit. In general, when nurses are asked similar questions at the work unit and organizational level, the questions that focus on the work unit score higher. This is also the case in this analysis, with many of the work-unit items scoring at the top of the distribution.

Work unit attributions are typically more favorable than organizational attributions. Work unit attributions are typically more favorable than organizational attributions. Attribution theory describes a self-serving bias, the tendency to view one’s successes as being driven by self and one’s failures driven by external influences (Larson, 1977). In nursing theory, we might describe this as a unit-affirming bias, the tendency to view one’s work unit more favorably than other units or the organization as a whole.

From 2013 to 2014, a drop in scores was identified in two key areas that are very much nurse-centric rather than organization-driven, and improvement was noted in employee connections (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Changes in Press Ganey Highest Scoring Employee Domain Items (Dempsey et al., 2015)

Note. EMP represents items that are associated with the Employee Domain.

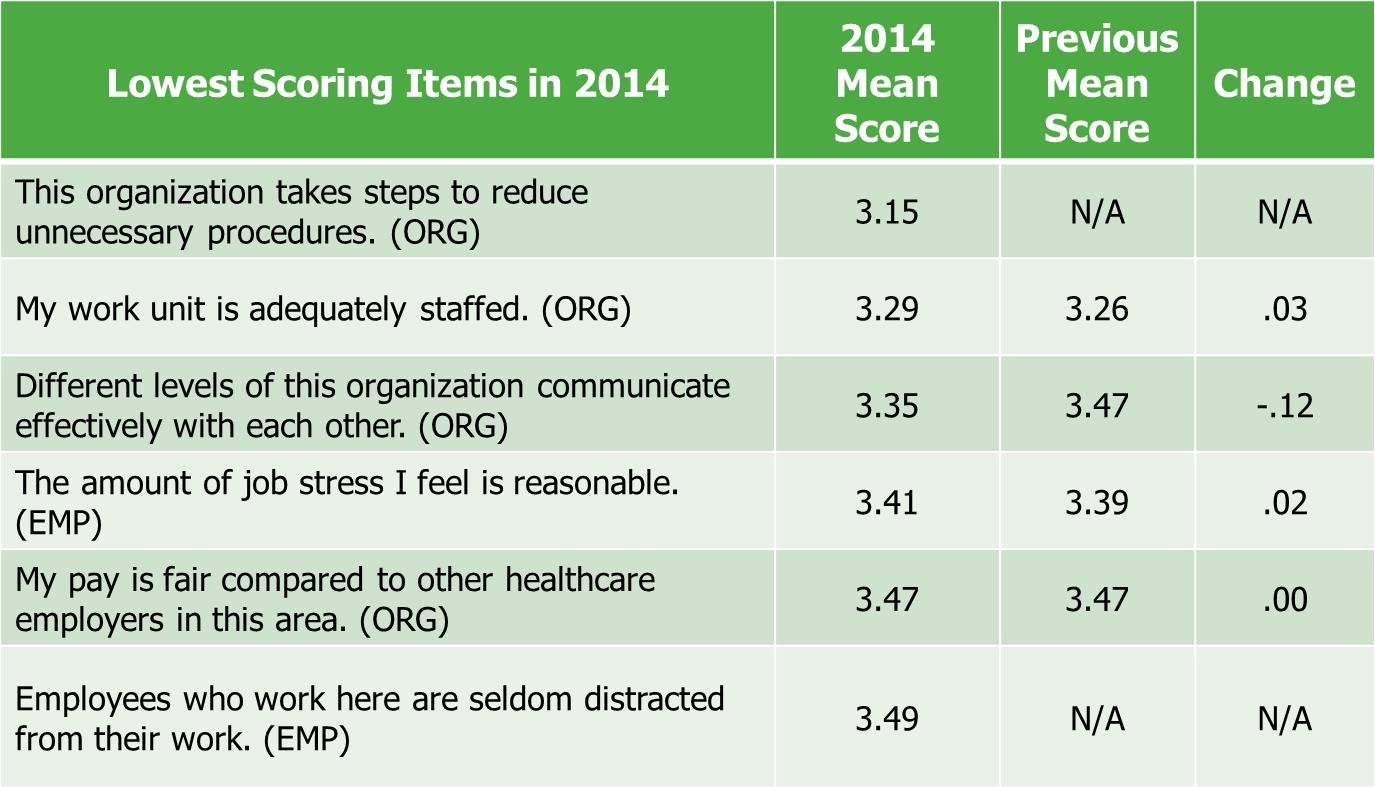

Lowest-scoring items for nurses are almost all related to their engagement to the organization. Lowest-scoring items for nurses are almost all related to their engagement to the organization. The examples in Figure 4 included: This organization takes steps to reduce unnecessary procedures; My work unit is adequately staffed; Different levels of this organization communicate effectively with each other; The amount of job stress I feel is reasonable; My pay is fair compared to other healthcare employers in this area; Employees who work here are seldom distracted from their work. Figure 4 also identifies some improvement in perceptions about staffing and stress, but a definite negative trend regarding interprofessional and organizational communication.

Figure 4. Changes in Press Ganey Lowest Scoring Employee Domain Items (Dempsey et al., 2015)

The decrease in communication effectiveness is remarkable and troubling. At a time when organizations are striving for more collaboration and communication, the downward trend of 0.12 in an already low communication item is worth noting. Despite, or perhaps because of, all the ways organizations have to communicate, we are not seeing the anticipated or desired progress. Communication between levels within an organization needs to be focused, intentional, and unceasing.

Length of Shifts

There appears to be a significant negative relationship between years of practice and longer shifts at the unit level, but the variability does not seem to be fully explained by influence over schedule, age, or unit type. Stimpfel and Aiken (2013) reported increased adverse events, errors, and complications associated with extended shift lengths. Further, their research demonstrated that across shift length categories, while more than 80% of nurses reported being satisfied with scheduling practices at their hospital, quality of the patient experience with longer shift lengths declined.

Ineffective staffing and scheduling processes are growing concerns among nurses... Percentages of nurses reporting burnout and an intention to leave the job increased incrementally as shift length increased. The percentage of nurses who were dissatisfied with the job was similar for nurses working the most common shift lengths, 8–9 hours and 12–13 hours, but it was higher for nurses working shifts of 10–11 hours and more than 13 hours. Ineffective staffing and scheduling processes are growing concerns among nurses and potentially impact the growing rates of compassion fatigue and burnout (Stimpfel & Aiken, 2013).

Additional Press Ganey cross domain analyses reveal significant relationships between nursing structural and cultural measures with nurses' global perceptions of their environment, patient perceptions of care, and patient clinical outcomes. Specifically, staffing, as defined by total nursing hours per patient day, is significantly and positively associated with nurses' overall job satisfaction and perception of the quality of care provided by the organization. Staffing is also positively associated with patient perceptions of care with higher staffing being associated with greater likelihood for patients to rate hospital care as a 9 or a 10 (of a possible 10) and greater likelihood for patients to indicate that nurses always demonstrated that they were listening to them (Press Ganey Nursing Special Report, 2015).

However, staffing alone does not ensure better clinical, quality, safety, and experience outcomes. Work environment is also a critical factor. The relative contributions of nurse staffing and work environment on patient and nurse outcomes suggest that the work environment of nurses can have as much or a greater impact than staffing on many safety, quality, experience, and value measures. Specifically, the analyses explore the relationships between an RN Work Environment Composite score and a Nurse Staffing Composite score on patient outcomes (falls, pressure ulcers, quality of care ratings, and patient experience ratings), nurse outcomes (job enjoyment, intent to stay and turnover), and publicly reported value outcomes (value-based purchasing, readmissions and hospital-acquired conditions; Press Ganey Nursing Special Report, 2015).

Review of the recent data related to nurse engagement above demonstrates the great variety of factors that can contribute to whether or not a nurse is engaged. In addition to the variables described above, compassion fatigue and burnout are also a part of the greater picture. The next section briefly describes these concepts related to nurse engagement and offers the results of a qualitative study seeking to address compassion satisfaction.

Compassion Fatigue and Burnout

A great deal of information has been written regarding compassion fatigue and burnout. These concepts are directly related to engagement, both with an organization and with the profession. There is no question that nurses are bombarded with distressing and complex physical and emotional challenges every day, in addition to dealing with personal issues they may face in their own lives.

Compassion fatigue was first identified by Joinson (1992) to describe the phenomenon of secondary trauma. Further, the antithesis of compassion fatigue, compassion satisfaction, has been described as attitudinal values (e.g., absorption, vigor, dynamism) that are experienced while conducting work-related tasks (Mason & Nel, 2012). Compassion satisfaction is negatively correlated to burnout, suggesting that higher compassion satisfaction may protect against the occurrence of burnout (Mason & Nel, 2012). Compassion satisfaction may then help to avoid disenchantment, or lack of meaning and purpose, as well as to avoid the isolation and loneliness of feeling disenfranchised, or powerless and marginalized.

The requirement that nurses demonstrate compassion in their interactions with patients and with each other may also become problematic in terms of engagement. First, compassion must be defined. According to Merriam-Webster, compassion is sympathetic consciousness of others' distress, together with a desire to alleviate it (Merriam-Webster, 2015). As the definition implies, it is a consciousness and a desire. Compassion is not the same as empathy. Empathy refers more generally to our ability to take the perspective of and feel the emotions of another person; compassion is when those feelings and thoughts include the desire to help.

Keltner (2004) cited research by Emory University neuroscientists James Rilling and Gregory Berns, (Rilling et al., 2002) in which participants were given the chance to help someone else while their brain activity was recorded. “Helping others triggered activity in the caudate nucleus and anterior cingulate, portions of the brain that turn on when people receive rewards or experience pleasure“ (para 7). If compassion is a biological trait, is it possible to teach and/or to learn compassion? Keltner (2004) further states that compassion is not a skill or virtue that we either have or not, but rather it is a trait that we can develop in an appropriate context. In other words, compassion can be taught.

An important question is whether or not we are preparing nurses to become engaged, as they are becoming nurses by providing compassion education? An important question is whether or not we are preparing nurses to become engaged, as they are becoming nurses by providing compassion education? Compassion is the action taken when one feels empathy. Studies have shown that empathy is decreasing and often lacking among nursing and medical students as well as nurses and physicians (Gurkova, Cap, Ziakova, & Duriskova 2011; Manzano Garcia, & Ayala Calvo 2011; Ozcan, Oflaz, & Bakir 2012). Many of these studies have cited issues such as the lack of positive role models, high volumes of material to learn, and lack of time as contributing factors to the decline in empathy.

Further complicating compassion education is the fact that much of what nurses must do is emotional labor. Hochschild (1983) stated that “… emotional labor involves the induction or suppression of feeling in order to sustain an outward appearance that produces in others a sense of being cared for in a convivial safe place” (p. 7). To do this likely requires nurses to behave and respond in ways that may not be congruent with their actual feelings. Over time, this ‘surface acting’ is associated with burnout. However, deep acting or the process of creating an internal emotional state that is congruent with the required action, may actually improve not only compassion, but engagement as well (Hochschild, 1983).

Compassionate Connected Care™ for the CareGiver

Avoidable suffering is suffering resulting from the dysfunction in our healthcare systems. Compassionate Connected Care™ was developed by Press Ganey with a purpose of addressing patient suffering. Patient suffering is a concept that has not traditionally been discussed (Lee, 2013) However, patients do suffer in terms of met and unmet needs that may be identified through data currently available both in Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) and Press Ganey survey data. Patient suffering has been identified as either inherent or avoidable. Inherent suffering is that arising from diagnoses and treatment even if healthcare were perfect. Avoidable suffering is suffering resulting from the dysfunction in our healthcare systems. The Compassionate Connected Care™ framework was developed as a means to understand the totality of the patient experience: clinical, operational, cultural, and behavioral.

In 2013, over 300 clinicians, nonclinicians, and patients were asked to provide a specific sentence that demonstrated what compassionate and connected care looked like. Participants provided 119 sentences and an affinity diagram was developed that identified the following six themes for Compassionate Connected Care ™ (Dempsey, Reilly, Noble, 2015):

- Acknowledge Suffering

- Coordinate Care

- Body Language Matters

- Anxiety is Suffering

- Real Caring Transcends Medical Diagnoses

- Autonomy Preserves Dignity

However, people who care for patients and their families also have met and unmet needs that may be determined by engagement data. To that end, a similar qualitative study by Press Ganey (2015) sought to identify strategies that might illustrate compassion, connectedness, and caring for people who care for patients at the bedside (e.g., nurses, doctors, transporters, and anyone who interacts with patients). Participants were voluntary and represented a cross section of caregivers from organizations across the United States. Over 1000 clinicians were asked to provide an image of what compassionate, connected care for the caregiver would look like. Participants were asked to provide specific examples or even images, rather than nebulous or generic examples, such as “Compassionate Connected Care for the CareGiver means my manager communicates well.” Rather, an example of a specific image might be: “Compassionate Connected Care for the CareGiver means that my manager rounds with me on my patients once a month.” A total of 185 images were returned via email, phone, Twitter, and LinkedIn. From those images, a content analysis revealed six themes to provide a roadmap by which to improve, and strategies to enable leadership to further engage the people who take care of patients every day. The six themes, briefly discussed below, with addition of supporting literature, were:

- We should acknowledge the complexity and gravity of the work provided by caregivers.

- It is the responsibility of management to provide support in the form of material, human, and emotional resources.

- Empathy and trust must be fostered and modeled.

- Teamwork is a vital component for success.

- Caregivers' perception of a positive work/life balance reduces compassion fatigue.

- Communication at all levels is foundational.

These themes provide general direction for employers to address needs of everyone who cares for patients.

Acknowledge the Work

...simply acknowledging efforts and praising good outcomes and behavior in a genuine and unscripted way is meaningful. Just as we must acknowledge that patients suffer and then respond accordingly, we must acknowledge that the work caregivers do is complex, important, and both physically and emotionally challenging. In addition, leaders and colleagues must recognize these efforts in tangible and intangible ways that demonstrate appreciation for the caregiver. This need not always be in monetary or tangible rewards. In fact, the images were not focused on compensation in any shape or form. Indeed, simply acknowledging efforts and praising good outcomes and behavior in a genuine and unscripted way is meaningful. The key piece of the acknowledgement is the understanding and empathy that transmits to a caregiver in a statement such as, “I really understand what you went through today.”

Provide Support from Leadership

Appropriate staffing must be assured based on acuity, complexity, and skill mix and not solely on volume. As demonstrated by Press Ganey’s cross domain analytics, staffing is important. But human resources are but one facet of resource management that is critical for leaders to assure good care for patients and the people who care for them. Leaders create the work environment. A positive environment is one in which the employee feels valued and supported (Bamford, Wong, & Laschinger 2013; Kelly, Kutney-Lee, Lake, & Aiken 2013). Appropriate staffing must be assured based on acuity, complexity, and skill mix and not solely on volume. Additionally, staffing must be well communicated so that those providing care understand the complexity and reality of budgetary and regulatory demands. Material resources necessary for care must be made available and be in good working order. Constantly searching for equipment or utilizing equipment that is not fully functional is inefficient, dangerous, and frustrating. Preventive maintenance and a proactive approach to capital management will have a much better return on investment than the lost productivity and potential turnover costs associated with the frustration and lack of engagement that insufficient beget (Aiken, 2008; McAlearney & Robbins 2013).

Foster Empathy and Trust

Trust is built on accountability, integrity, and fidelity at all levels of the organization. Empathy and trust are critical to creating a positive work environment (Post et al, 2014; Reynolds, Scott, & Austin, 2000). Trust is built on accountability, integrity, and fidelity at all levels of the organization. Consistency and empowerment that have been so foundational for shared governance help to instill trust in leadership and colleagues. Empathy, not only for patients but also for caregivers means treating one another with respect and anticipating others’ needs. This empathy and trust for each other and the organization must be embedded within the culture of the organization for it to be tangible in the care for patients.

Support Teamwork

Teams that work together consistently and with the same patient populations express better engagement... Care of patients is not accomplished by a solo practitioner. It takes a interdisciplinary team of experts and support personnel to provide the best care of the patient in the best place for their care by the best people to provide that care. These teams must be coordinated around the patients’ needs and diagnoses, not around convenience of the caregivers or the organization. Teams that work together consistently and with the same patient populations express better engagement with the organization and demonstrate better outcomes (Choi, Bergquist-Beringer, & Staggs 2013; Choi & Boyle, 2013; Davidson, Dunton, & Christopher, 2009; Pavlish & Hunt, 2012).

Encourage Work/Life Balance

Caregivers must feel that the work they do is meaningful and purposeful. A positive work/life balance is increasingly important as the millennials begin to dominate the workplace (Jobe, 2014; Piper, 2012). This is a generational fact and must be taken into account with scheduling, training, and communication with caregivers. Caregivers must feel that the work they do is meaningful and purposeful. Much of what we do in healthcare is task oriented and checklist driven. Caregivers need to be reminded frequently that what they do is important and impacts the lives of their patients and their families in ways that they may never know. Caregivers want to leave work a “good tired” - that is, they may be tired from a long day, but knowing they gave their patients excellent care and feeling good about that care when they finish their shift. When a nurse or other caregiver begins to experience burnout or compassion fatigue, leaders must intervene quickly and appropriately so that the employee is able to receive help and his or her attitude does not influence other colleagues (Bakker, Le Blanc, & Schaufeli, 2005; Coetzee & Klopper, 2010).

Ensure Communication

Clear, direct, and timely communication of clinical impressions and plans among all team members is critical... Communication is foundational. Communication and transparency are fundamental for the demonstration of empathy and trust. Listening is a key component of communication and often is not demonstrated either by leadership with employees or by caregivers with patients and families. Transparency of data, and providing opportunities to discuss the data and opportunities for improvement, allow the people at the bedside to determine improvement strategies and drive accountability and ownership for improvement efforts (Bakker & Keithley, 2013; McAlearney et al, 2013). Clear, direct, and timely communication of clinical impressions and plans among all team members is critical to align focus and messaging to the patient and provide optimal care and outcomes.

Conclusion

...nurse engagement is critical to the patient experience, clinical quality, and patient outcomes. Nurse engagement and patient experience are not “nice to haves,” nor are they considerations to address “when we have time.” As the data and research have demonstrated, nurse engagement is critical to the patient experience, clinical quality, and patient outcomes. Nurse engagement with the organization and the profession reduces compassion fatigue, burnout, and turnover while improving teamwork, the patient experience, and organizational outcomes across multiple measures: clinically (fewer hospital acquired conditions), operationally (staffing and efficiency), culturally (positive work environment and empowerment), and behaviorally (ability to connect with patients and colleagues).

While the qualitative work described here demonstrates themes that will inform strategies to improve engagement, further research on optimal staffing and scheduling must be conducted to help us understand how to reduce stress and burnout, as well as negative clinical indicators identified with longer shifts. To engage patients, nurses must be able to find meaning and belonging, both within the profession and within the organization. Compassionate connected care for nurses can better equip nurses to provide compassionate and connected care for patients and their families across the care continuum.

Authors

Christina Dempsey, MSN, MBA, RN, CNOR, CENP

Email: cdempsey@pressganey.com

Christina Dempsey is the Chief Nursing Officer for Press Ganey Associates, Incorporated in South Bend, Indiana. Ms. Dempsey also serves as a faculty member for the Missouri State University Department of Nursing.

Barbara A. Reilly, PhD

Email: Barbara.reilly@pressganey.com

Barbara Reilly is the SVP of Employee, Nurse, Physician Engagement for Press Ganey Associates, Incorporated in South Bend, Indiana.

NSI Nursing Solutions, Inc. (2015). 2015 National healthcare retention & RN staffing report. East Petersburg, PA: Author. www.nsinursingsolutions.com/Files/assets/library/retention-institute/NationalHealthcareRNRetentionReport2015.pdf

References

Aiken, L. H. (2008). Economics of nursing. Policy, Politics, and Nursing Practice, 9(2): 73–79.

Bakker, A. B., Le Blanc, P. M., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2005). Burnout contagion among intensive care nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 51(3), 276-287.

Bakker, D., & Keithley, J. K. (2013). Implementing a centralized nurse-sensitive indicator management initiative in a community hospital. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 28(3), 241-249. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0b013e31827c6c80.

Bamford, M., Wong, C. A., & Laschinger, H. (2013). The influence of authentic leadership and areas of work-life on work engagement of registered nurses. The Journal of Nursing Management, 21(3), 529-540. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2012.01399.x

Brown, S. (2012, August 23). The science of compassion: origins, measures, and interventions [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RZGJV5TRk_c

Bryan, A. (2015, September 16).’Show me your stethoscope,’ nurse Facebook group response to’ The View.’ WTVR.com. Retrieved from http://wtvr.com/2015/09/16/show-me-your-stethoscope-nurse-facebook-group-responds-to-the-view/

Choi, J., Bergquist-Beringer, S., & Staggs, V. S. (2013). Linking RN workgroup satisfaction to pressure ulcers among older adults on acute care hospital units. Research in Nursing and Health, 36(2), 181-190. doi: 10.1002/nur.21531.

Choi, J., & Boyle, D.K. (2013). RN workgroup job satisfaction and patient falls in acute care hospital units. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 43(11), 586-591. doi: 10.1097/01.NNA.0000434509.66749.7c.

Coetzee, S. K., & Klopper, H.C. (2010). Compassion fatigue within nursing practice: A concept analysis. Nursing and Health Sciences, 12(2), 235-243. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2010.00526.x.

Davidson, J., Dunton, N., & Christopher, A. (2009). Following the trail: Connecting unit characteristics with never events. Nursing Management, 40(2), 15-19.

Day, H. (2014). Engaging staff to deliver compassionate care and reduce harm. British Journal of Nursing, 23(18), 974-980 7p. doi:10.12968/bjon.2014.23.18.974.

Dempsey, C, Reilly, B.A., & Noble, B. (2015, June 22). Strengthening culture: Nurse engagement insights to inform HR strategies [Webinar]. Retrieved from http://www.pressganey.com.

Dempsey, C; Wojciechowski, S.; McConville, E.; Drain, M. (2014, October). Reducing patient suffering through compassionate connected care. Journal of Nursing Administration, 44(10), 517-524. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000110.

France, L.R. (2015, September 16). After #NursesUnite,’ View’ hosts says comments about nurse misconstrued. CNN. Retrieved from: http://www.cnn.com/2015/09/16/entertainment/the-view-nurses-collins-behar-fiorina-feat/

Gurkova, E., Cap, J., Ziakova, K., & Duriskova, M. (2011). Job satisfaction and emotional subjective well-being among Slovak nurses. International Nursing Review 59(1), 94–100. DOI:10.1111/nuf.12056

Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The managed heart: commercialization of human feeling. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Jobe, L. L. (2014). Generational differences in work ethic among 3 generations of registered nurses. Journal of Nursing Administration, 44(5), 303-308. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000071.

Joinson, C. (1992). Coping with compassion fatigue. Nursing, 22(4), 116, 118-119.

Kelly, D., Kutney-Lee, A., Lake, E. T., & Aiken, L. H. (2013). The critical care work environment and nurse-reported health care-associated infections. American Journal of Critical Care, 22(6), 482-488. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2013298 . Retrieved from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3996829/

Keltner, D. (2004, March 1). The compassionate instinct. Greater Good. Retrieved from http://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/the_compassionate_instinct.

Laschinger, H. K. S., & Leiter, M. P. (2006). The impact of nursing work environments on patient safety outcomes: The mediating role of burnout engagement. Journal of Nursing Administration, 36(5), 259-267.

Larson, J. R. (1977). Evidence for a self-serving bias in the attribution of causality. Journal of Personality, 45(3), 430–441.

Lee, T.H. (2013), The word that shall not be spoken. New England Journal of Medicine, 369:1777-1779 doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1309660.

Manzano Garcia, G., & Ayala Calvo J. C. (2011) Emotional exhaustion of nursing staff: Influence of emotional annoyance and resilience. International Nursing Review 59(1), 101–107. doi:10.1111/j.1466-7657.2011.00927.x

Mason, H. D., & Nel, J. A. (2012). Compassion fatigue, burnout and compassion satisfaction: Prevalence among nursing students. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 22(3), 451-455.

McAlearney, A. S., & Robbins, J. (2013). Using high-performance work practices in health care organizations a perspective for nursing. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 29(2), 11-20. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0b013e3182a813f3.

Merriam-Webster. (2015). Compassion. Retrieved from http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/compassion

Meyer, J. P. (2013). The science–practice gap and employee engagement: It’s a matter of principle. Canadian Psychology, 54(4), 235-245. doi: 10.1037/a0034521

Nishioka, V.M., Coe, M.T., Hanita, M., & Moscato, S.R. (2014). Dedicated education unit: Student perspectives. Nursing Education Perspectives, 35(5), 301-307. doi: 10.5480/14-1380

NJ.com. (2015). Miss Colorado skips the song and dance, talks about nursing.[Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nYoCW1DQWQE

NSI Nursing Solutions, Inc. (2015). 2015 National healthcare retention & RN staffing report. East Petersburg, PA: Author. www.nsinursingsolutions.com/Files/assets/library/retention-institute/NationalHealthcareRNRetentionReport2015.pdf

Ozcan, C.T., Oflaz, F., & Bakir, B. (2012). The effect of a structured empathy course on the students of a medical and a nursing school. International Nursing Review, 59(4), 532-538. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2012.01019.x

Pavlish, C., & Hunt, R. (2012). An exploratory study about meaningful work in acute care nursing. Nursing Forum, 47(2), 113 -122. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6198.2012.00261.x.

Piper, L. E. (2012). Generation Y in healthcare: Leading millennials in an era of reform. Frontiers of Health Services Management, 29(1), 16-28.

Post, S. G., Ng, L. E., Fischel, J. E., Bennett, M., Bily, L., Chandran, L., . . . Roess, M. W. (2014). Routine, empathic and compassionate patient care: Definitions, development, obstacles, education and beneficiaries. Journal of Evaluation and Clinical Practice, 20(6), 872-880. doi: 10.1111/jep.12243

Press Ganey Associates, Inc. (2015). Press Ganey nursing special report: The influence of nurse work environment on patient, payment and nurse outcomes in acute care settings. South Bend, IN: Author.

Press Ganey Associates, Inc. (2013). Every voice matters: The bottom line on employee and physician engagement. South Bend, IN: Author. Retrieved from: http://healthcare.pressganey.com/2013-PI-Every_Voice_Matters

Reynolds, W., Scott, P. A., & Austin, W. (2000). Nursing, empathy and perception of the moral. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 32(1), 235-242.

Rilling, J., Gutman, D., Zeh, T., Pagnoni, G., Berns, G., & Kilts, C. (2002). A neural basis for social cooperation. Neuron, 35(2), 395-405.

Sawatzky, J. A., & Enns, C. L. (2012). Exploring the key predictors of retention in emergency nurses. Journal of Nursing Management, 20(5), 696-707.

Schaufenbuel, K. (2013). Powering your bottom line through employee engagement. UNC Kenan-Flagler Business School. Retrieved from: http://execdev.kenan-flagler.unc.edu/powering-your-bottom-line-through-employee-engagement

Stimpfel, A. W., & Aiken, L. H. (2013). Hospital staff nurses' shift length associated with safety and quality of care. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 28(2), 122-129. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0b013e3182725f09