The COVID-19 pandemic has reset the table for a dialogue about health equity, public health, and the future of nursing. Experts anticipated that payment reforms would lead to a much-needed increase in community and public health nursing. Despite calls for the profession of nursing to take a leadership role in addressing the social determinants of health and health equity, data show that jobs for nurses in community-based clinics and public health have actually declined in the last decade. This article offers background on the ongoing decline in public health infrastructure in the United States, an analysis of workforce data on nursing jobs using the National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses from the years 2000, 2004, 2008, and 2018, and the National Association of County and City Health Officials from 2008 to 2019, as well as a discussion of why these findings are so troubling. We discuss policy implications for nurse educators related to curricula and clinical experiences, and for professional nursing organizations as they set goals to increase and improve nursing jobs in community clinics and public health settings. In conclusion, we note that the federal investments in community health centers and public health nursing provide a short window of opportunity to reverse the historic and ongoing decline and rebuild a stronger community and public health nurse workforce.

Key Words: Nursing, COVID-19, public health workforce, public health nursing, community health nursing

Among the many problems that the COVID-19 pandemic brought to the fore in the United States were two: health inequities and the crumbling public health infrastructure and workforce in most parts of the country. Both have become priorities for the new federal administration, and significant resources are now available to strengthen the nursing workforce in community-based and public health settings (ARP, 2021).

It is well known that pre-pandemic, investment in the public health workforce has been declining for at least 15 years.It is well known that pre-pandemic, investment in the public health workforce has been declining for at least 15 years. This is one reason why the social determinants of health (SDOH) that drive healthcare and other inequities have not been adequately addressed (Castrucci & Lupi, 2020). What is less well known is that participation by nurses has been falling faster than other professional groups within the public health workforce. This article discusses the reduced participation by nurses in both public health and community-based clinics, and discusses implications for the future.

Background

Public health and community health nurses are not new to this country. Indeed, they were a central force in healthcare from 1910 to 1940, losing prominence only as the medical model of care and the rise of hospitals gained traction through the mid-20th century (Pittman, 2019b). Efforts to revitalize public health nursing have continued over time, especially by organizations such as the Association for State and Territorial Directors of Nursing (ASTDN) (now the Association of Public Health Nurses).

Figure 1 shows the range of activities public health nurses are engaged in, all of which are essential contributions to address health equity. Since the early 1940s, there has been a general convention that at least one public health nurse is needed per 5,000 population. In 2008, the ASTDN called for the formalization of this goal, and specifically for additional nurse supervisors, and a higher density of public health nurses in high poverty communities (Keller & Litt, 2008).

Figure 1. Contributions of Community/Public Health Nurses

|

Many predicted that value-based payment would provide an incentive for healthcare organizations to hire more nurses outside of hospitals...Following the 2010 Affordable Care Act (Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 2010), experts hoped that progress was being made toward addressing healthcare inequities with this change to the healthcare infrastructure. Many predicted that value-based payment would provide an incentive for healthcare organizations to hire more nurses outside of hospitals, in areas such as public health and community-based settings (Larson, 2017; Pittman & Forrest, 2015; Salmond & Echevarria, 2017). The rationale was that as hospitals assumed more risk under Accountable Care Organizations and other value-based payment programs, care would shift outside of the hospital to ambulatory settings and homes. We would invest in public health and upstream initiatives, such as coordination with social services, housing, and food security. (Larson, 2017). Some chief nursing officers in hospitals were even calling for large health systems to create a chief nursing officer position for community-based nursing (Pittman & Forrest, 2015).

...many argued that nurse leaders should emphasize the importance of recommitting to the foundational practice of public health nursing...At the same time, many argued that nurse leaders should emphasize the importance of recommitting to the foundational practice of public health nursing, as exemplified by Lillian Wald in the period of 1910 to the late 1930s (Hassmiller, 2013; Pittman, 2019a; Sullivan-Marx, 2020). This call became more compelling as researchers identified a surge in so-called diseases of despair (i.e., primarily behavioral health-related challenges) and noted that the centralized medical model based in hospitals was failing. The increased interest in SDOH, driven in part by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Culture of Health goal (n.d.), and the continued emphasis on deepening outcome-based payment in health reform, also highlighted the promise of models that function at the intersection of nursing and social work.

When the COVID-19 pandemic appeared in early 2020, nurses in critical care settings occupied the headlines. The reported shortage of critical care nurses renewed appreciation for the essential role hospitals play during a public health emergency. Nurses who were working in intensive care units under dangerous physical and emotional conditions were hailed as heroes and seen as the symbol of the entire profession. Nothing about this shift in the conversation was unfair or regrettable. However, as has happened numerous times in the last half-century, the fear of a nursing shortage in hospitals, for a time, pushed the issue of community and public health nursing aside, once again (Pittman, 2019a).

...the fear of a nursing shortage in hospitals, for a time, pushed the issue of community and public health nursing aside, once again.When the Biden Administration took office in 2021, priorities shifted and the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for public health and health equity became center stage. On January 21st, one day after assuming office, President Biden issued an Executive Order that established a Public Health Workforce Program. This order would determine how to deploy personnel in future public health threats; establish a five-year budget requirement for a sustainable public health workforce, including Public Health Service Commissioned Corps; and establish a U.S. Public Health Job Corp that would conduct contact tracing, assist in vaccination outreach and administration, and assist with training to provide testing (Biden, 2021).

Implicit in this measure was an acknowledgment that the prevention of community spread of COVID-19 could be improved. Beyond the perceived mismanagement and politicization of the pandemic by the former administration by many, the new policies reflected the notion that more could have been done to prevent the spread with a robust public health workforce in the community. Public health infrastructure had not been a priority for many years (Taylor, 2018). Areas of weakness noted in the current pandemic included coordination between local, state, and federal roles; community education on the importance of public health prevention measures, surveillance through contact training, COVID-19 testing, and planning for the vaccine rollout (Sullivan-Marx, 2020).

An example that demonstrates the importance of a robust infrastructure concerns the vaccine rollout.An example that demonstrates the importance of a robust infrastructure concerns the vaccine rollout. West Virginia and New Mexico were far more successful in quickly vaccinating their residents than others. These two rural states had maintained a stronger public health infrastructure than other states. They turned to their public health workforce, rather than the fragmented private sector pharmacy and healthcare delivery system, during the vaccine roll-out, taking vaccines to hard-to-reach populations (Cunningham, 2021).

In March, Congress passed the American Rescue Plan Act (ARP) of 2021. The ARP provides a significant funds for the public health workforce through multiple mechanisms, including funding for local health departments. In keeping with the goals announced in the earlier Executive Order (Biden, 2021), $7.66 billion in the new law is targeted to establish, expand, and sustain a public health workforce, including awards to state, local, and territorial public health departments (ARP, 2021).

...it is important to understand whether payment reforms and the calls for nurses to address SDOH were indeed having an effect before the pandemic.As we contemplate the implications of this new opportunity for nurses and the profession of nursing, it is important to understand whether payment reforms and the calls for nurses to address SDOH were indeed having an effect before the pandemic. In order words, where does the nursing workforce stand today, and is it positioned to expand its role in community health and public health?

In this analysis, we question the progress made prior to the 2020 pandemic in terms of strengthening community-based and public health nursing and discuss the implication of the recent legislation (ARP, 2021) for the future of community and public health nursing.

Analysis of Workforce Data

...not only did the expected expansion of nursing into community and public health settings not occur, but the trendlines were headed in the wrong direction. We analyzed the last four iterations (2000, 2004, 2008, and 2018) of the National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses (NSSRN), performed by the National Center for Health Workforce Analysis ([NCHWA], 2018), and data from the National Association of County and City Health Officials ([NACCHO], 2019) from 2008 to 2019. Our analysis included evaluation of the data in these documents over time and consideration of other trends. Using the NSSRN over time, we first conducted descriptive analysis on changes in nurse employment in community and public health settings, as well as in other primary care settings. We also examined county and city employment data over time to trace back a sub-set of community/public health nurses, i.e.,nurses in local health departments, and compared with trends of other occupations employed in local health departments. These findings revealed that not only did the expected expansion of nursing in to community and public health settings not occur, but the trends were headed in the wrong direction.

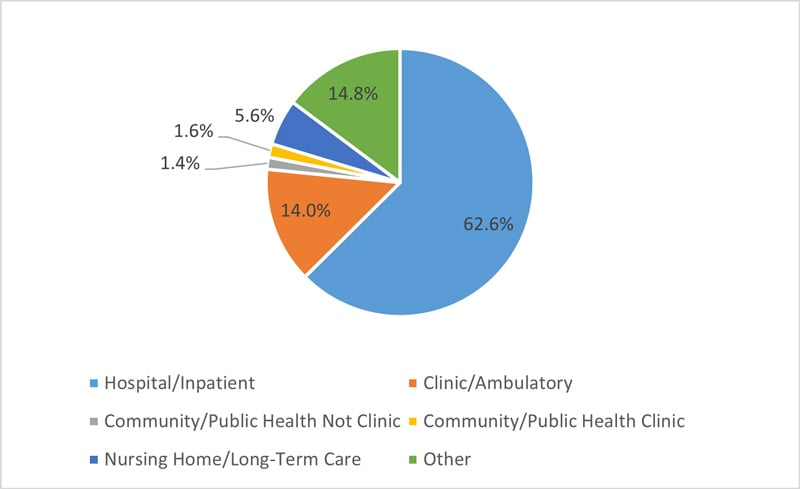

...current distribution of nurses is still weighted heavily toward hospital employment.As shown in Figure 2, data from the most recent NSSRN (2018) revealed that the current distribution of nurses is still weighted heavily toward hospital employment (62.6%). Just 1.4 % of registered nurses (RNs) are employed in community/public health non-clinic settings (e.g., state health or mental health agency; city or county health department), and 1.6% are employed in public health/community clinic-based settings (e.g., rural health center, Federally Qualified Health Center [FQHC], Indian Health Service, TRIBAL Clinic), for a combined 3% of the nurse workforce.

Figure 2. Distribution of RNs by Employment Setting 2018 (n= 3,272,871)

*PH/CH not clinic-based includes State Health or Mental Health Agency, City or County Health Department. PH/CH clinic-based includes Rural Health Center, FQHC, Indian Health Service, TRIBAL Clinic, etc.

Source: Authors’ Analysis Based on the National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses, 2018 (NCHWA, 2018)

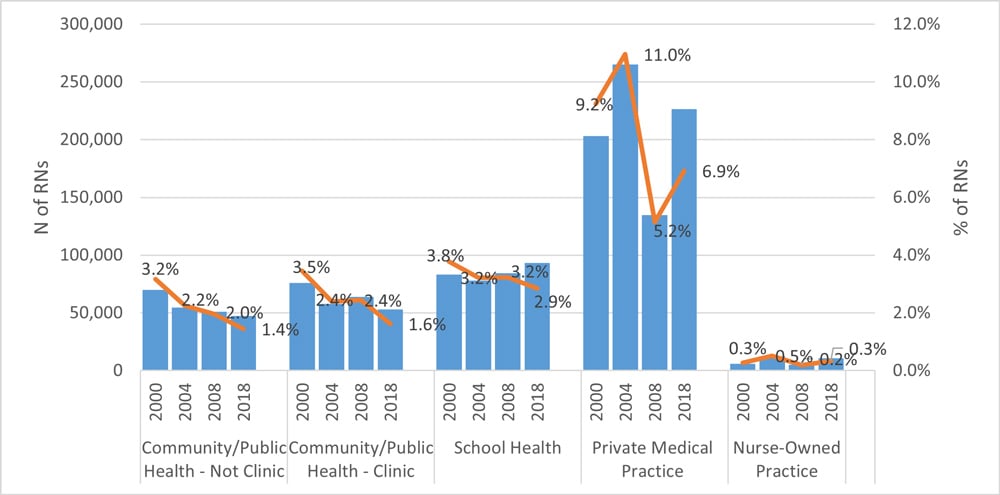

...RNs in both clinic and non-clinic-based community/public health jobs dropped dramatically.Analysis of NSSRN Over Time

When we examined the NSSRN (2000; 2004; 2008; 2018) over time, we saw a clear and discouraging trend. As shown in Figure 3, RNs in both clinic and non-clinic-based community/public health jobs dropped dramatically. RNs in non-clinic-based community/public health jobs fell as a percent of the total RN workforce from 3.2% (69,837) in 2000 to just 1.4 % (47,226) in 2018. There was a similar drop in clinic-based jobs, from 3.5% (76,127) to 1.6% (53,084). The Table provides the descriptive data used to compile Figure 3.

Figure 3. RNs in Community/Public Health*, 2000-2018

*PH/CH not clinic-based includes State Health or Mental Health Agency, City or County Health Department. PH/CH clinic-based includes Rural Health Center, FQHC, Indian Health Service, TRIBAL Clinic, etc.

Source: Authors’ Analysis Based on the National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses, 2000, 2004, 2008 and 2018 (NCHWA, 2018)

Table. Descriptive Data for Figure 3

|

Year |

RNs employed |

Community/ Public Health Not Clinic |

Community/ Public Health Clinic |

School Health |

Private Medical Practice |

Nurse-Owned Practice |

|||||

|

|

|

N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

|

2000 |

2,201,813 |

69,837 |

3.2% |

76,127 |

3.5% |

83,269 |

3.8% |

203,346 |

9.2% |

5,978 |

0.3% |

|

2004 |

2,421,351 |

54,460 |

2.2% |

57,878 |

2.4% |

78,022 |

3.2% |

265,273 |

11.0% |

12,500 |

0.5% |

|

2008 |

2,616,971 |

51,104 |

2.0% |

63,867 |

2.4% |

84,418 |

3.2% |

134,881 |

5.2% |

4,968 |

0.2% |

|

2018 |

3,272,871 |

47,226 |

1.4% |

53,084 |

1.6% |

93,344 |

2.9% |

226,524 |

6.9% |

10,655 |

0.3% |

Primary care settings (beyond the publicly-funded community clinics described above) cannot be traced back to the early NSSRN surveys (2000; 2004; 2008), so we examined two other categories: private medical practice and nurse-owned practices. The decline was less dramatic than in community health/public health, but we found a drop in nurses employed in private medical practice from 9.2% in 2000 to 6.9% in 2018, again with a slight increase in the absolute numbers (203,346 to 226,524). Nurse-owned practices remained flat at just .3% over time, even with the absolute numbers almost doubling from 5,978 to 10,655 (NCHWA, 2018).

Other Trends

Trends in additional non-hospital categories also challenged the predictions. For example, school -based nurses declined as a percentage of the total nurse workforce, from 3.8% to 2.9%, although their actual numbers increased by a little over 10,000 (83,269 to 93,344) (NCHWA, 2018).

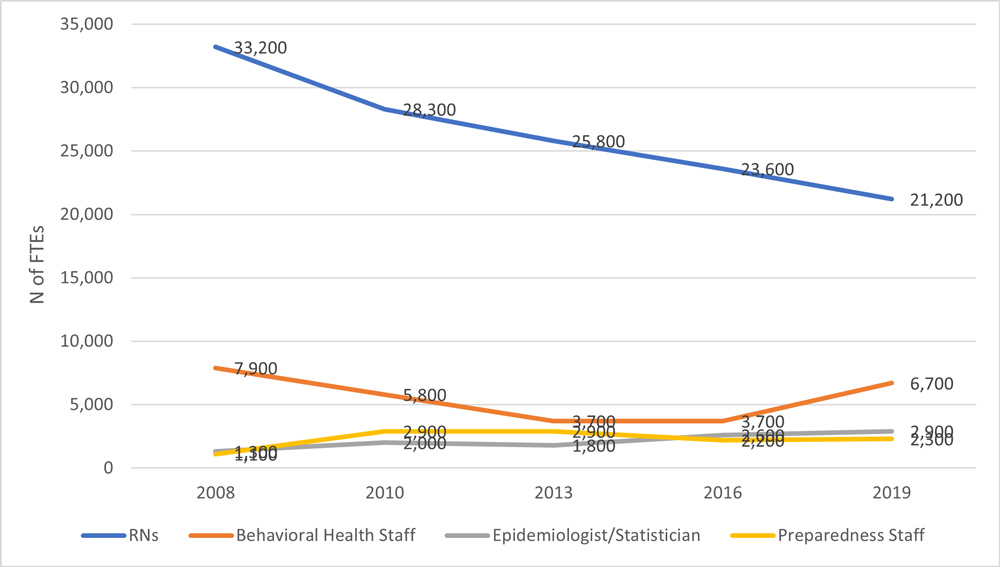

...the decrease of nurses was faster than any other occupation within public health.To understand why there are not more public health nurses, it is also worth looking at data on a sub-set of public health nurses: those working in local health departments. These nurses are a critical part of the governmental response to any public health crisis, including COVID-19. We analyzed county and city health employment data (NACCHO, 2019) from the years 2008-2019. As shown in Figure 4, the number of nurses declined from just over 33,000 to just over 21,000. This decline mirrors the NSSRN data presented in Figure 3, but it also reveals another puzzling data point: the decrease of nurses was faster than any other occupation within public health. Behavioral health staff were falling but have had a significant uptick since 2016. Other staff, such as epidemiologists and preparedness staff, have increased slightly over time (NACCHO, 2019).

Figure 4: RNs and other Occupations in Local Health Departments, 2008-2019

Source: Authors’ Analysis of 2019 National Profile of Local Health Departments, National Association of County and City Health Officials (2019)

Discussion

The question, then, is why public health nursing has been particularly hard hit during this period since the year 2000? Edmonds and colleagues (2020) warned against replacing public health nurses with less costly personnel in their Call to Action for Public Health Nurses, arguing that nurses’ “preparation, knowledge, clinical decision'making skills, and their ability to flexibly be deployed across a diverse range of activities in response to rapidly evolving public health needs” make them irreplaceable in public health (Edmonds et al., 2020, p. 324) However, the data above do not suggest substitution

At least part of the problem appears to be on the supply side.Local health departments seem to agree. In a 2017 survey of local health departments in California, 80% reported problems with recruitment or retention of nurses, and 46% reported a decrease in nurses on staff (Taylor, 2018).This finding suggests that it is not simply a problem of low job availability or a lack of appreciation for nursing contributions in these settings. They indicated that they want more nurses.

At least part of the problem appears to be on the supply side. It is possible thatthe interest in career advancement and continued education has led the workforceto greater specialization. Specialization in nursing, as in medicine, could be drivingthe workforce away from primary care, community-based care, and public health,and into hospitals and specialty physician offices.

Competition from acute care settings may also be hurting community-based healthcare and public health.Competition from acute care settings may also be hurting community-based healthcare and public health. The same California survey (Taylor, 2018) found that nurses reported that low compensation was a major reason for considering leaving their local health department jobs. Indeed, the most recent NSSRN (2018) showed that the mean annual salary for nurses in hospital settings was $76,506 versus $66,632 for those in public health departments (NCHWA, 2018). More jobs without increased compensation may, therefore, be an insufficient remedy.

It is incumbent on nursing and health policy leaders in a variety of settings to do more.

Policy Implications

Current information suggests that the payment reforms and marketplace alone are insufficient to expand nursing in the community clinics and public health. It is incumbent on nursing and health policy leaders in a variety of settings to do more. In addition to remuneration issues, the supply of nurses graduating with a focus on community and public health may also be less than is needed for an expansion.

Implications for Nursing Education

First, nursing program faculty should review curricula and bolster educational offerings in community-based healthcare and public health as appropriate. Program leaders need to identify role models in public health and offer community and public health practice settings for students to conduct clinical practice requirements. If nurses are prepared for this type of work, they may be more likely to rise within the ranks of public health departments, earn a higher salary, and report greater job satisfaction.

Non-traditional practice would teach students about unique and critical roles of public health workers from other backgrounds...Second, boards of nursing in some states still require a nurse preceptor for clinical hours. For public health nurses, allowing preceptors with various non nursing backgrounds would be beneficial. Such a policy could increase the availability of clinical sites and expose nursing students to the work of interprofessional teams before they graduate. Rather than seeing these occupations as a threat, Lillian Wald, the foundational public health nurse in the early 20th century, saw the partnership with social work as critical to addressing community needs (Pittman, 2019a). Non-traditional practice would teach students about unique and critical roles of public health workers from other backgrounds, particularly social workers and community health workers.

Implications for Goal Setting

Third and last, measurable goals would spur action. An example of this is evident from the Institute of Medicine report on the Future of Nursing ([IOM], 2011), which set a goal of 80% of the nurse workforce attaining a bachelor of science level education by 2020. This measurable goal drove change in a positive direction, even if the goal was not fully attained. While public health nurses are but one component of the community and primary-based workforce needed, ASTDN has delineated an achievable set of goals for public health nursing. (Spetz, 2018) Organizations that support primary care, community-based, and school-based nurses could do the same.

...measurable goals would spur action.The ASTDN goals are (1) one public health nurse per 5,000 population, (2) an additional 1:8 ratio for supervisors to nurses, and (3) more nurses in high-need communities. These goals suggest the need for 66,284 non-clinic-based community/public health nurses to meet the 1: 5,000 ratio, plus an additional 8,284 additional public health nurse supervisors as recommended by ASTDN. Based on the most recent estimate of 47,226 nurses in public health roles (NSSRN, 2018), we would need another 27,341 public health nurses to meet the first criterion of the ASTDN goal. More would be required to meet the needs of high poverty communities, depending on the criteria used to identify those communities.

One advantage of this type of goal is that nursing schools could estimate the number of new graduates per year specialized in public health needed in each region; public health departments could do the same. Federal health workforce program administrators could track how their programs contribute to this goal at a national and a local level. Examples of these programs are the Nurse Corps loan repayment program, which received additional funding under the American Rescue Plan Act (Health Resources and Services Administration, 2020), and Title VIII, which funds various nurse education programs and received extra support under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (2020).

Conclusion

Events of the COVID-19 pandemic have reset the table for the healthcare workforce and specifically the profession of nursing. Even more clear is the danger of allowing our public health infrastructure to decay, as this analysis of nurses in the public health workforce alone suggests has happened.

Even more clear is the danger of allowing our public health infrastructure to decay...To attract more nurses to this field, public and private employers will need to address relative compensation issues. Nursing programs will need to produce more nurses who are interested in and prepared to practice in community and public health. Local, state, and federal public health workforce programs will need to set measurable goals by region and publicly track progress.

The combined emphasis on equity and the public health workforce of the current administration provides a window of opportunity to reverse the historic, ongoing declines briefly described in this article in community and public health nursing. Rebuilding a stronger nurse workforce will not only prepare the United States to meet the challenges of future pandemics, but also have a positive upstream impact on the SDOH-related inequities that are endemic.

Authors

Patricia Pittman, PhD, FAAN

Email: ppittman@gwu.edu

Patricia Pittman is the Fitzhugh Mullan Professor of Health Workforce Equity at the Milken Institute School of Public Health, George Washington University. As director of the Mullan Institute for Health Workforce Equity, Professor Pittman she leads an extensive research, action and education enterprise that focuses on advancing policies that enable the health workforce to better address health equity, including protection of labor rights of health workers. Her current portfolio includes directing two HRSA-supported Health Workforce Research Centers.

Jeongyoung Park, PhD

Email: jpark14@gwu.edu

Dr. Jeongyoung Park is an Assistant Professor at the George Washington University School of Nursing and a faculty member at the Fitzhugh Mullan Institute for Health Workforce Equity (Mullan Institute). Dr. Park is a health services researcher at the intersection of nursing, health policy, and health economics. Her research interests include healthcare delivery and payment system changes, and its impacts on health workforce and patient outcomes.

References

American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, H.R. 1319, 117th Cong. (2021). https://docs.house.gov/billsthisweek/20210308/BILLS-117HR1319EAS.pdf

Biden, J. R. (2021, January 21). Executive order on establishing the COVID-19 pandemic testing board and ensuring a sustainable public health workforce for COVID-19 and other biological threats. The White House. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/01/21/executive-order-establishing-the-covid-19-pandemic-testing-board-and-ensuring-a-sustainable-public-health-workforce-for-covid-19-and-other-biological-threats/

Castrucci, B., & Lupi, M. V. (2020, May 19). When we need them most, the number of public health workers continues to decline. deBeaumont. https://debeaumont.org/news/2020/when-we-need-them-most-the-number-of-public-health-workers-continues-to-decline/#:~:text=Since%20the%20Great%20Recession%2C%20state,fifth%20of%20the%20total%20workforce.&text=The%20number%20of%20employees%20in,is%20also%20about%2015%20percent

Cunningham, P. W. (2021, February 4). The health 202: How West Virginia beat other states in administering coronavirus vaccines. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/02/04/health-202-how-west-virginia-beat-other-states-administering-coronavirus-vaccines/

Edmonds, J. K., Kniepp, S. M., & Campbell, L. (2020). A call to action for public health nurses during the COVID'19 pandemic. Public Health Nursing, 37(3), 323-324. doi: 10.1111/phn.12733

Han, X,. Barnow, B., & Pittman, P. (in press). Alternative approaches to ensuring adequate nurse staffing: A difference-in-difference evaluation of state legislation on hospital nurse staffing. Medical Care

Hassmiller, S. (2013). The RWJF’s investment in nursing to strengthen the health of individuals, families, and communities. Health Affairs, 32(11), 2051-2055. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0819

Health Resources and Services Administration. (2020). Meet Nurse Corps service requirements. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/funding/meet-service-requirements

Institute of Medicine Committee on the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Initiative on the Future of Nursing. (2011). The future of nursing: Leading change, advancing health. The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/12956

Keller, L. O., & Litt, E. A. (2008, September). Report on a public health nurse to population ratio. Association of State and Territorial Directors of Nursing. www.cphno.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/ASTHOReportPublicHealthNursetoPopRatio2008.pdf

Larson, T. (Ed.). (2017). Registered nurses: Partners in transforming primary care. Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation. https://macyfoundation.org/assets/reports/publications/macy_monograph_nurses_2016_webpdf.pdf

National Association of County and City Health Officials. (2019). 2019 national profile of local health departments. https://www.naccho.org/profile-report-dashboard/workforce-composition

National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. (2018). National sample survey of registered nurses, 2018 [Data set]. Health Resources and Services Administration. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/nursing-workforce-survey-data

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 42 U.S.C. § 18001. (2010). https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-111publ148/pdf/PLAW-111publ148.pdf

Pittman, P. (2019a). Rising to the challenge: Re-Embracing the Wald model of nursing. American Journal of Nursing, 119(7), 46-52. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000569444.12412.89

Pittman, P. (2019b, March 12). Activating nursing to address unmet needs in the 21st century. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. https://publichealth.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/downloads/HPM/Activating%20Nursing%20To%20Address%20Unmet%20Needs%20In%20The%2021st%20Century.pdf

Pittman, P., & Forrest, E. (2015). The changing roles of registered nurses in Pioneer Accountable Care Organizations. Nursing Outlook, 63(5), 554-565. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2015.05.008

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. (n.d.). Building a culture of health. https://www.rwjf.org/en/how-we-work/building-a-culture-of-health.html

Salmond, S. W., & Echevarria, M. (2017). Healthcare transformation and changing roles for nursing. Orthopedic Nursing, 36(1), 12-25. doi: 10.1097%2FNOR.0000000000000308

Spetz, J. (2018). More nurses with bachelor's degrees required to meet future health care needs. Nursing Outlook, 66(4), 394-400

Sullivan-Marx, E. (2020). Public health nursing: Leading in communities to uphold dignity and further progress. Nursing Outlook, 68(4), 377-379. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2020.07.001

Taylor, S. (2018, January 5). Reversing the decline of public health nurse retention and recruitment in California, 2017. Campaign for Action. https://campaignforaction.org/resource/reversing-decline-public-health-nurse-retention-recruitment-california-2017/