The COVID-19 pandemic placed many nurses in financial distress. Nurses House, Inc. provided nurses with financial assistance through an emergency grant supported by the American Nurses Foundation. In a three-month period between April 2020 till July 2020, Nurses House, Inc. distributed $2,734,500 to a total of 2,484 qualified grantees from across the United States. This article offers a brief review of literature to provide context about the guiding framework of the grant, Watson’s Theory of Human Caring, as an essential tenet to nursing and to the mission of Nurses House, Inc, and the financial impact of the pandemic. We discuss the methods, data analysis, and results of our study that analyzed demographic information from the applications of grant recipients. Regression analysis showed that regardless of income levels, nurses experienced financial distress. The discussion considers our findings in relation to such areas as age and full-time or part-time work status of grantees; reasons to apply, such as testing positive for COVID=19 (78%), work mandated quarantine (16%) and caring for a family member (6%); and study limitations. The conclusion offers implications for practice based on our analysis, which demonstrated that financial safety nets are both essential and helpful for nurses in times of crisis.

Key Words: COVID-19, nurses in financial distress, financial safety net, Watson’s Theory of Human Caring, Nurses House, Inc

The International Year of the Nurse, 2020, began as a year to recognize the instrumental role nurses and midwives play in healthcare delivery, raise awareness of challenges they often experience, and advocate for solutions for workforce issues (World Health Organization [WHO], 2021). It was a fitting tribute to the 200th anniversary of the birth of Florence Nightingale, founder of modern nursing, to celebrate nurses worldwide. What accompanied that designation that no one could foresee was a global coronavirus pandemic that would place nurses around the world on the front line of the response.

One aspect of the pandemic that has received little attention is its financial impact on nurses.One aspect of the pandemic that has received little attention is its financial impact on nurses. Exploration of the experiences of those nurses for whom the pandemic introduced financial distress, such as those who tested positive for the virus or had to care for family members diagnosed with COVID-19, enriches our understanding about the complex impact of a pandemic on the nursing workforce. Financial distress typically occurs when people are unable to pay their bills (Hayes, 2021). Those who worry about the ability to meet normal monthly living expenses and live on a paycheck-to-paycheck basis are also likely to experience financial distress (Garman & Sorhaindo, 2005).

Nurses House, Inc. provided nurses with financial assistance through an emergency grant supported by the American Nurses Foundation during a three-month period between April 2020 till July 2020. A sample of nurses who experienced financial distress in direct relation to the COVID-19 pandemic was available from nurses who applied to Nurses House, Inc. for temporary monetary support. Examination of the de-identified data obtained from recipient grant applications provided valuable descriptive information to increase our understanding of the financial impact of COVID-19 on nurses.

...financial safety nets for nurses are warranted in times of crisis...This article offers a brief review of literature to provide context about the guiding framework of the grant, Watson’s Theory of Human Caring, as an essential tenet to nursing and to the mission of Nurses House, Inc., and the financial impact of the pandemic. We discuss our retrospective descriptive study that analyzed demographic information from the applications of grant recipients. Our conclusion offers implications for practice based on this analysis, which demonstrated that financial safety nets for nurses are warranted in times of crisis such as we have experienced with the coronavirus pandemic.

Requests by nurses for financial support are based on physical or mental health problems.

Nurses House, Inc.

Founded in 1922 with a grant from Emily Howard Bourne, Nurses House, Inc. is a nurse-managed, non-profit organization whose mission is to provide short-term financial assistance to registered nurses (RNs) in need as a result of illness, injury, or disability (Nurses House, n.d.). Requests by nurses for financial support are based on physical or mental health problems. In March 2020, as the nation was confronted by the pandemic, the Nurses House Inc. Board of Directors (BOD) approved a temporary COVID-19 Emergency Grant for nurses financially threatened by the pandemic circumstances. In partnership with the American Nurses Foundation (ANF), Nurses House, Inc. established a COVID-19 fund to provide grants to registered nurses (RNs) and licensed practical nurses/licensed vocational nurses (LPNs/LVNs) throughout the United States (US) who experienced financial distress due to the coronavirus pandemic (Dague et al., 2020).

Review of Literature

Caring

Caring is the core of nursing.Caring is the core of nursing (Nightingale, 1859; Skretkowicz & Nightingale, 1992). Adams (2016) asserted that "the construct of caring remains critical to the nursing profession perhaps even more now than in the past…" (pg.1). It is up to nurses to ensure that caring in nursing transcends turbulent times and remains at the forefront of patient care (Adams, 2016). Watson’s (1979, 1985) Theory of Human Caring or Theory of Transpersonal Caring is foundational to the field of nursing. Watson and Smith (2002) asserted caring is the central feature within the metaparadigm of nursing knowledge and practices, bringing meaning to the nursing profession as a distinct healthcare profession. This resulted in Watson developing the 10 Carative Factors and associated processes. (see Table 1 below).

Table 1 – 10 Carative factors and cartias processes

|

Original 10 Carative Factors, juxtaposed against the emerging Caritas Processes/Carative Factors |

Caritas Processes |

|

1. Humanist – Altruistic Values |

1. Practicing Loving-kindness & equanimity for self and other |

|

2. Instilling/enabling Faith & Hope |

2. Being authentically present to/enabling/sustaining/honoring deep brief system and subjective world of self/other |

|

3. Cultivation of Sensitivity to one’s self and other |

3. Cultivating of one’s own spiritual practice; deepening self-awareness, going beyond “ego self” |

|

4. Development of helping-trusting, human caring relationship |

4. Developing and sustaining a help-trusting, authentic caring relationships |

|

5. Promotion and acceptance of expression of positive and negative feelings |

5. Being present to, and supportive of, the expression of positive and negative feelings as a connection with deeper spirit of self and the one-being-cared-for |

|

6. Systemic use of scientific (creative) problem-solving caring process. |

6. Creatively using presence of self and all ways of knowing/multiple ways of Being/doing as part of the caring process: engaging in artistry of caring-healing practices |

|

7. Promotion of transpersonal teaching-learning |

7. Engaging in genuine teaching-learning experiences that attend to whole person, their meaning, attempting to stay within other’s frame of reference |

|

8. Provision for a supportive, protective, and/or corrective mental, social, spiritual environment |

8. Creating healing environment at all levels (physical, non-physical, subtle environment of energy and consciousness whereby wholeness, beauty, comfort, dignity and peace are potentiated |

|

9. Assistance with gratification of human needs |

9. Assisting with basic needs, with an intentional, caring consciousness of touching and working with embodied spirit of individual, honoring unity of Being; allowing for spiritual emergence |

|

10. Allowance for existential-phenomenological spiritual dimensions |

10. Opening and attending to spiritual-mysterious, unknown existential dimensions of life-death, attending to soul care for self and one-being-cared-for |

...caring science connects nurses, patients, families, and all healthcare professionals in authentic human caring relationships.Thus, caring science connects nurses, patients, families, and all healthcare professionals in authentic human caring relationships (Ackerman, 2019). Further, the Code of Ethics for Nurses requires nurses to care for other nurses (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2015).

We deemed three of Watson’s Carative Factors particularly relevant to the experience of nurses who applied for COVID-19 emergency grants due to financial distress. These factors aligned Watson’s Carative Factors with her associated Carative processes. The first we viewed as applicable was Factor #1: Human-Altruistic Values, explained as practicing loving-kindness and equanimity for self and others. Second, we determined that development of a helping-trusting human caring relationship (Factor #4) resulting in an authentic caring relationship was pertinent. Finally, we identified Factor #9 as germane, specifically assistance with gratification of human needs explained as assisting with basic needs, with an intentional, caring consciousness of touching and working with embodied spirit of individual, honoring unity of Being (Gallagher-Lepak & Kubsch, 2009). These three factors served to describe the nature of the interaction of the nurses included in this study as they cared for others, recognized their need for care, and were cared for by Nurses House, Inc. In addition, the caring processes have been exemplified by the Nurses House, Inc./ANF response to helping nurses in financial distress from COVID-19 and provided an exemplar to articulate human caring in action.

COVID-19

To differentiate among the viruses that caused outbreaks of respiratory illness, the WHO named the virus that initially caused the disease in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China in 2019 as COVID-19 (Lai et al., 2020). On January 21, 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirmed the first case of COVID-19 in the United States. On March 11, 2020, because of the rapid spread across continents, WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic (Lai et al., 2020). On March 13, 2020, the President of the United States declared the illness a national emergency. By early 2021, total cases in the United States surged to over 25 million with over 450,000 Americans succumbing to the virus (CDC, 2021; American Journal of Managed Care, 2021).

...healthcare workers caring for COVID-19 patients were at high risk.Individuals with COVID-19 could be asymptomatic carriers or they displayed an array of symptoms, including fever, malaise, cough, dyspnea, headache, diarrhea, nausea, and loss of taste or smell (CDC, 2021; Lai et al., 2020; Menni et al., 2020). While all individuals were at risk for COVID-19, older adults; individuals in congregate living centers; individuals with co-morbidities; racial and ethnic minority groups; young infants; and healthcare workers caring for COVID-19 patients were at high risk (CDC, 2020; Dong et al., 2020; Leung et al., 2020)

Financial Impact

In the general population, the COVID-19 pandemic has had a multifaceted effect on the lives of most citizens in the United States. To identify the most serious health and financial problems encountered in the country, National Public Radio (NPR), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health (2020) conducted a survey from July 1 to August 3, 2020 in the four largest urban areas in the United States. They surveyed a "representative, probability-based, address-based sample of adults age 18 or older," which was comprised of 3,454 adults; 512 lived in New York City, 507 in Los Angeles, 529 in Chicago, and 447 in Houston (NPR, RWJF, & Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, 2020, p.1). Data were presented as percentage of households, not individuals.

...half or more households in all four cities were experiencing serious financial problems associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.The NPR, RWJF, and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health (2020) survey revealed that half or more households in all four cities were experiencing serious financial problems associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Serious financial problems were reported by 53% of households in New York City, 56% in Los Angeles, 50% in Chicago, and 63% in Houston. These serious financial problems were associated with loss of jobs, job furlough, or wage or hours reduction. The specific ways in which these problems manifested included using all/most of savings; inability to pay bills, including mortgage or rent, utilities, car payments, credit cards, and loans; and serious problems paying for necessities, including food and medical care. These findings were consistent from responders across all four cities. It is important to note that these people represented the general population, not a survey of nurses (NPR, RWJF, & Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, 2020).

The investigators included the percentage of respondents from their sample who reported a household member who worked in healthcare. The percentage of households with at least one member working in healthcare ranged from 11% (one in 10 households) in Houston to 20% (one in five) in Los Angeles. In addition, they reported concerns with their safety as well as their finances. Because these data were not specific to nurses, it cannot be assumed that the NPR, RWJF, and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health (2020) survey was representative of the nurses who sought support from the Nurse House, Inc. COVID-19 grant. However, this information does provide additional perspective about financial concerns associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in general. Examination of the data from the accepted COVID-19 emergency applications to Nurses House, Inc. (i.e., grantees) provided more specific information related to financial impact on this subgroup of nurses.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective descriptive study by reviewing applications to the emergency fund that was distributed between April and July 2020 to provide financial assistance to nurses directly affected by the coronavirus pandemic. To be eligible for the grant, applicants had to supply documentation confirming that they were currently employed as a nurse but temporarily unable to work due to COVID- 19. Applicants had to select one of the following reasons for being unable to work: tested positive for COVID-19, had a work-mandated quarantine, or stayed at home to care for a family member with COVID-19. In addition, the following information was collected from each applicant:

- Basic demographic information (e.g., name, address, date of birth, contact information, gender)

- A copy of their current RN or LPN/LVN license

- Place of employment, employment status (fulltime or parttime), and supervisor contact information

- Usual income and a copy of their most recent paystub

- A copy of their positive COVID-19 test or documentation from their employer or primary care provider indicating they were exposed and quarantined from work for a period of time

- Size of household

Applicants applied via the Nurses House Inc. website at www.nurseshouse.org. Each application was reviewed by the Nurses House, Inc. Director, a master’s prepared RN, who determined the eligibility of each applicant. If the applicant met the set criteria, the applicant was approved, and a check was mailed to them. The COVID-19 grant program closed on July 8, 2020. In total, Nurses House, Inc. distributed $2,734,500 in the three-month grant period to a total of 2,484 qualified grantees from across the United States.

To increase understanding of those grantees who received financial assistance, de-identified data from the grantees were analyzed. The focus of these analyses was to describe the circumstances of nurses who applied to and the met the qualifications of Nurses House, Inc. for financial support due to employment disruption which caused economic impact from COVID-19 and to consider the role of "caring" as pertains to those circumstances. Niagara University institutional review board (IRB) granted approval for the study.

Data Analysis and Results

Grantee Demographic Data

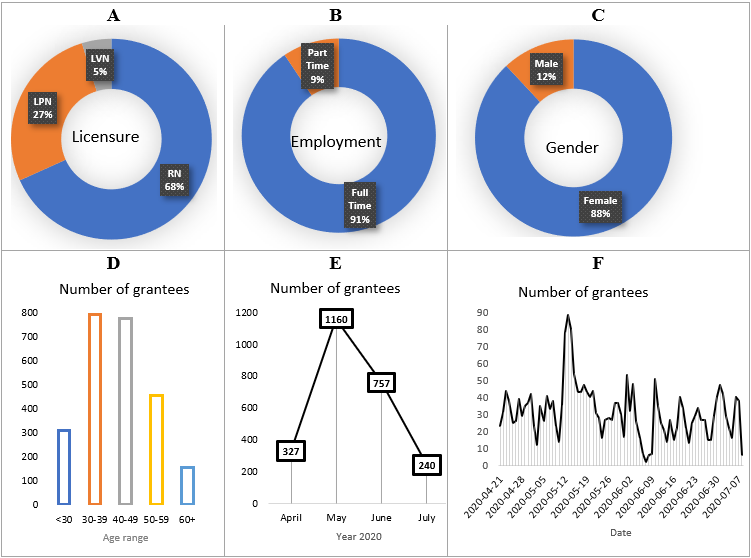

Of the 2,800 applications received, 2,484 (88.7%) applicants qualified for the grant. Figure 1 summarizes the demographic data: 68% of grantees were RNs (n = 1,696), 27% (n = 670) were LPNs, and 5% (n = 118) were LVNs. The majority of grantees (91%, n = 2,250) were employed full-time, while 9% (n = 234) worked part-time. About half of the grantees (49.6%) worked in an acute care setting and about a quarter (24.7%) worked in rehabilitation or long-term care facilities. The rest worked in various other clinical and administrative settings. Both males and females were represented; however, female nurses represented a larger (88%) portion than male nurses.

Of the 2,800 applications received, 2,484 (88.7%) applicants qualified for the grant.Nurses less than 30 years old accounted for 12% of grantees (n = 307). Grantees in the age range of 30 to 39 accounted for 32% (n = 791), those in the age range of 40 to 49 accounted for 31% (n = 774), those in the age range of 50 to 59 accounted for 18% (n = 456), and the remainder (age range 60 and above) accounted for 6% (n = 156). Overall, the average age of the grantees was 42, while the median age was 41. The maximum age was 75; the minimum age was 21.

Thirteen percent of accepted applications (n = 324) were submitted in April, 47% (n = 1160) in May, 30% in June (n = 757), and 10% in July (n = 240). The largest single-day number of applications (n = 88) were submitted on May 13, 2020.

Figure 1. Basic Demographic Information of Grantees

Reasons for Applying for Grant

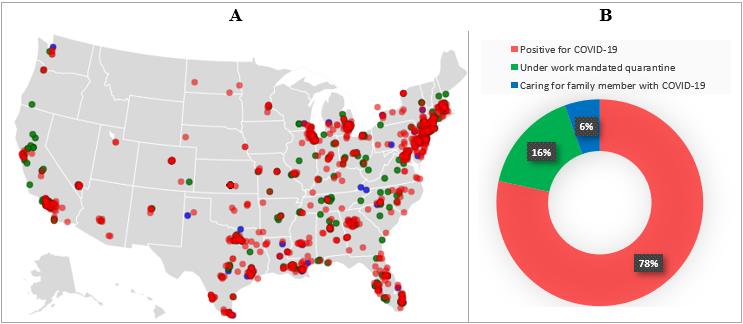

...the greatest reason for applying was due to the grantees personally having been positive for COVID-19.Reasons reported for applying to the Nurses House, Inc. grant provided insight into circumstances that contributed to financial distress. Grantees had to select one of the options for this being unable to work. Figure 2 shows that 78% of grantees (n = 1,947) reported having tested positive for COVID-19, 16% (n = 400) reported that they were under work-mandated quarantine, and 6% (n = 137) indicated that they were caring for a family member with COVID-19. Thus, the greatest reason for applying was due to the grantees personally having been positive for COVID-19.

Figure 2. Reasons for Applying for the Grant, Portrayed Using a Geochart (A) And a Pie Chart (B).

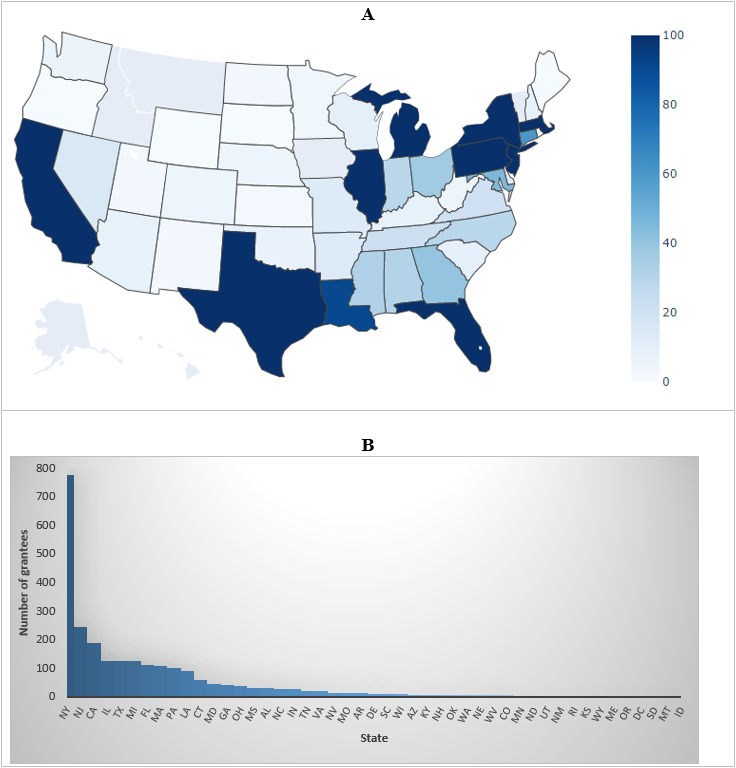

Geographic Distribution of Grantees

The distribution of grantees across geographic region provided further descriptive information. The darkest blue shading in Figure 3 highlights nine states (NY, NJ, CA, IL, TX, MI, FL, MA, and PA) with at least 100 qualified grantees. These states combined constituted about 77% (n = 1,904) of all grantees. Of all states, NY had the greatest number of grantees (31%, n = 777). Six states (AK, VT, HI, MT, IA, and ID) had no qualified applicants.

Figure 3. Number Of Grantees by State (A) and the Overall Share of Each State (B).

NOTE: The darker the blue color, the more number of grantees.

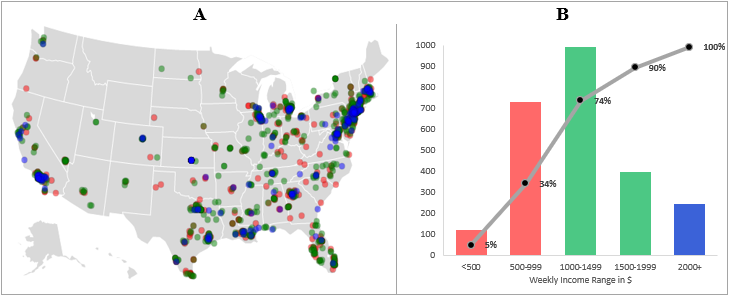

Incomes of Grantees

The application also queried grantees about their usual income, which provided information about their economic background. Figure 4 indicates that about 34% of grantees (n = 851) had a weekly income less of than $1,000; about 55% of grantees (n = 1,388) had a weekly income in the range of $1,000 to $2,000; and a smaller number of applicants (n = 254 or 10%) had a weekly income greater or equal to $2,000. The average weekly income was $1241, while the median income was $1123. The greatest portion of grantees were in the weekly income range of $1,000 to $1,499. Total family income was not required for the application. Income data have been presented in relation to the geographic region of the nurses who were awarded the grant.

Figure 4. Grantees Weekly Income, Portrayed Using a Geochart (A) and a Histogram (B).

Household Size of Grantees

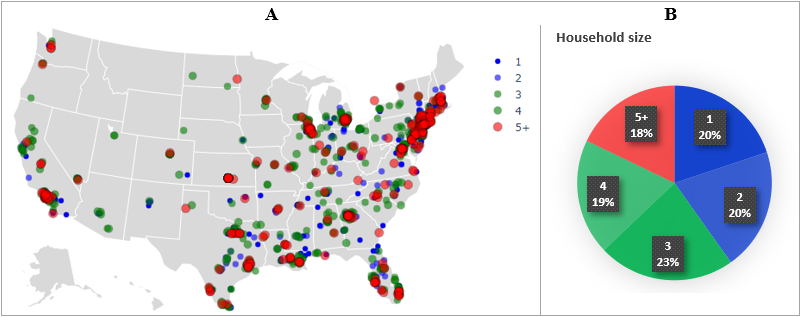

The grant application included household size to determine the number of people who may be associated with the reported income and for whom the grantees may have responsibility or interact with in their families. Figure 5 indicates household sizes of grantees and how they distributed across regions in the United States. Grantee household size ranged from one to six persons.

The smallest household size, grantees living alone, was reported by 19.9% of the grantees (n = 494). Two people in the household were reported by 20.3% (n=504). Other grantee households consisted of three (22.7%; n= 564) or four people (19.2%; n=478). The fewest group of grantees were those who reported households of five people (12.4%; n=309) or six or more (5%; n=135). Grantees living alone or in households of two, three, or four members accounted for the greatest percentage and were equally distributed at approximately 20% each.

Figure 5. Grantees by Household Size, Portrayed Using a Geochart (A) and a Pie Chart (B).

We also considered the demographic information in the context of the recipient’s reason to apply for the grant. Demographic information by variables of age, gender, licensure, household size, employment, and weekly income is presented in Table 2 for each of the three eligibility criteria.

Table 2. Demographic Information of Grantees by the Reason to Apply

|

Variables |

Reason for applying for the grant |

||

|

Positive for COVID-19 (n = 1947) |

Caring for family member with COVID-19 (n = 137) |

Under Work -mandated Quarantine (n=400) |

|

|

n (%) |

n (%) |

n (%) |

|

|

Age |

|||

|

≤ 30 |

229 (11.8) |

19 (13.9) |

59 (14.8) |

|

Gender |

|||

|

Female |

1696 (87.1) |

123 (89.8) |

368 (92.0) |

|

Licensure |

|||

|

RN |

1329 (68.3) |

89 (65.0) |

278 (69.5) |

|

Household Size |

|||

|

1 |

405 (20.8) |

9 (6.6) |

80 (20.0) |

|

Employment |

|||

|

Full time |

1784 (91.6) |

117 (85.4) |

349 (87.2) |

|

Weekly Income |

|||

|

≤$499 |

84 (4.3) |

13 (9.5) |

24 (6.0) |

|

Note. n (%) signify the number and percentage of grantees in the respective category. |

|||

The data were analyzed as to what extent these recipient demographics could explain the reason for applying for the emergency grant according to the three options: positive for COVID-19, caring for a family member, or under mandated quarantine. Table 3 summarizes a series of logistic regressions where age, weekly income, household size, gender, licensure, and employment were covariates. The responses were binarized (1 for yes and 0 for no) for each nominal reason for applying.

Table 3. A Series of Independent Logistic Regressions Using Applicant Demographics as Covariates and Each Reason for Applying as a Binary Response

Reasons

|

Covariates |

Positive for COVID-19 |

Caring for Family Member with COVID-19 |

Under Work Mandated Quarantine |

||||||

|

Coef |

Sig. |

OR |

Coef |

Sig. |

OR |

Coef |

Sig. |

OR |

|

|

Constant |

0.05 |

0.85 |

|

-1.80 |

0.00 |

|

-0.40 |

0.174 |

|

|

Age |

0.02 |

0.00* |

1.03 |

-0.03 |

0.01* |

0.974 |

-0.02 |

0.00* |

0.98 |

|

Weekly Income |

0.00 |

0.08 |

1.00 |

0.00 |

0.06 |

1.000 |

0.00 |

0.40 |

1.00 |

|

Household Size |

0.06 |

0.06 |

0.94 |

0.23 |

0.00* |

1.259 |

-0.01 |

0.77 |

0.99 |

|

Gender a |

0.47 |

0.01* |

1.60 |

-0.15 |

0.60 |

0.859 |

-0.54 |

0.01* |

0.58 |

|

Licensure b |

0.11 |

0.33 |

0.90 |

-0.01 |

0.94 |

0.986 |

0.14 |

0.25 |

1.16 |

|

Employment c |

0.36 |

0.02* |

1.44 |

-0.30 |

0.26 |

0.743 |

-0.31 |

0.07 |

0.73 |

NOTE: Instead of one multinomial regression model, a series of separate binary logistic regressions are run to interpret the reason for applying directly, without a reference variable. The presented results are consistent with the outcomes of a related multinomial regression. Covariates are treated as continuous in the SPSS statistical package. Coef means coefficient, OR stands for odds ratio, and Sig. represents the statistical significance.

a Gender is coded as 1 (female) and 0 (male)

b License is coded as 1 (RN) and 0 (other)

c Employment is coded as 1 (Full time) and 0 (Part time)

*p-value <0.05

Discussion

...no particular demographic differences were noted in the grantees by licensure.This study sought to describe the demographics and characteristics of nurses who experienced financial distress during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and who received a financial assistance grant from Nurses House, Inc. While there was representation from both RNs and LPNs/LVNs, no particular demographic differences were noted in the grantees by licensure. Regarding employment status, both full-time (91%) and part-time (9%) nurses applied at percentages that are almost consistent with national surveys which report that about 12% of nurses tend to work part-time (Smiley et. al., 2019). As presented in Table 2, a greater number of grantees working full time indicated a positive COVID-19 test as the reason for applying, as compared to those with part-time status. All other factors equal, full-time nurses likely had more exposure time from caring for patients with COVID-19 (See Figures 1, parts A and B).

Results by gender (See Figure 1, part C) were consistent with national surveys that reported female nurses comprise about 90% of the nursing workforce (Smiley et al., 2019). Notably, female grantees were 1.6 times more likely to apply due to a positive COVID-19 test than male grantees, when all other variables were held constant (See Table 3). The odds of applying due to work-mandated quarantine were almost half (0.58 times) for female grantees as compared to male grantees.

The number of nurses applying for financial assistance...raises an alarm regarding the financial vulnerability of the nursing workforce.The number of nurses applying for financial assistance from Nurses House, Inc. raises an alarm regarding the financial vulnerability of the nursing workforce. Despite earning almost two times the annual median wage of all workers, $39,810 compared to $73,300 (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020), nurses reported experiencing financial distress due to an inability to work for relatively short periods of time. The female-dominated nature of the nursing workforce is a microcosm of larger gender-based social inequities that disadvantage women in the workforce. This creates a greater likelihood of women experiencing financial distress, which has been amplified by the pandemic. Kashen et al. (2020) reported four times as many women as men dropped out of the labor force in September 2020, with the lack of childcare cited as the reason by one in four women.

In a report analyzing data from the Current Population Survey (IPUMS-CPS) and the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), Streeter and Deevy (2019) found the median income of all working men aged 25 and over was 30% higher than that of working women, and that single women, including divorced, widowed, and never married, suffer a much higher likelihood of falling into poverty than single men. Additionally, they found that women often are employed in more flexible jobs to meet family needs, such as caring for children or an elderly parent; however, these more flexible jobs often permanently set them on a lower-earning career path. Employment in these flexible positions ultimately increases vulnerability to reductions in work hours and job layoffs. Specific to nursing, the gender wage gap also continues to widen. A nationwide survey conducted in 2020 of more than 7,400 nurses found women making $7,200 less than men, which represented a $1,600 increase in the wage gap since the 2018 survey (Nurse.com, 2020).

The female-dominated nature of the nursing workforce is a microcosm of larger gender-based social inequities that disadvantage women in the workforce.All adult age groups were represented, with a median age of 41 (See Figure 1, part A). This statistic is lower than the median age of U.S. nurses, which is 53 for RNs and 54 for LPNs/LVNs (Smiley et al., 2019). Most grantees tended to be younger than the national average and were in the 30 to 50 years age range. Of the cumulative distribution of the age group, 75% of all applicants were less than age 50 (See Figure 1, part A). Results presented in Table 3 further reveal that, holding all other variables constant, the odds for applying due to a positive COVID-19 test were slightly higher for each unit increase in the age. However, the odds of applying because of caring for a family member or being under work-mandated quarantine slightly decreased as age increased.

In this study, females (88%) in the age range of 30 to 50 years old (66%) accounted for most of the grantees. While the predominant reason for applying was the grantee having tested positive for COVID-19, this suggests additional possibilities based on gender, such as childcare responsibilities for women of this age group and salary differential. These data were not obtained in this study, but future exploration may be of interest.

The timeframe for the submitting applications was limited by Nurses House, Inc. The number of applications received was highest in May, two months the after the President declared the illness a U.S. National Emergency, and then gradually decreased. This suggests that a group of nurses experienced financial distress fairly rapidly in association with the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic was first declared in March, and the applications which provided the source of these data were received between April and July, with the greatest percentage in May. Reasons for applying did not vary by month. Grantees represented almost every state in the United States (See Figure 3), with the highest numbers in areas of the epicenters of cases. This is consistent with the ANF (2020) findings.

This suggests that a group of nurses experienced financial distress fairly rapidly in association with the COVID-19 pandemic.The findings suggest that the grantees felt financial distress either after testing positive for COVID-19, being placed under mandatory quarantine, or having to take time off to care for a family member with COVID-19. In most cases, the grantees indicated that they were at greater risk of losing a significant share of their income since they could no longer go to work. Several categorical characteristics of the applicants (See Table 2) with further analysis of demographics using a series of logistic regressions (See Table 3) helped to explain the odds of applying for financial help due to a positive COVID-19 test, mandated quarantine, or caring for a family member with COVID-19.

Regarding income level (See Figure 4), contrary to what one may speculate, there was no indication that nurses with a relatively low income tended to apply at a greater rate than those reporting higher income levels. Applications received included a non-trivial number of medium to high-income nurses. For example, the analysis of salary suggested that the median weekly income of RN applicants was about $1,200. When annualized, this income is about $62,400, which is on par with the reported national median annual salary of RNs of $63,000 (Smiley et al., 2019). However, the ANF (2020) survey administered to 10,099 nurses found that 56% of the respondents were worse off financially as a result of the COVID-19 outbreak. In addition, 57% of the respondents to the ANF survey indicated that it would take from one month to two years for their finances to recover from the pandemic and related economic crisis.

About 60% of grantees had a household size of three or more.About 60% of grantees (n = 1,486) had a household size of three or more. As for the household size from one to six, there was almost equal representation in each category (about 20% each), apart from the larger household sizes (five at 12.4% and six at 5%) (See Figure 5). In other words, nurses of most family sizes felt the same financial vulnerability. As one may expect, while keeping all other variables unchanged, the odds of applying because the applicant was caring for a family member increased with each unit increase in the household size (See Table 3). It would have been interesting to have data about how many of the household members besides the grantee were employed or how many persons were being supported by the grantee alone. It would also have been interesting to learn whether other employed members of a household also had their employment status affected by COVID-19 events.

...a significant share of nurses reported being worse off or indicated they had experienced unexpected financial needs due to COVID-19.The presumption from these analyses is that some nurses experienced financial distress due to COVID-19. This conclusion is consistent with surveys from the ANF (2020), which have suggested a significant share of nurses reported being worse off or indicated they had experienced unexpected financial needs due to COVID-19. The economic impact of COVID-19 is not unique to nurses as several millions of Americans have been financially affected by this pandemic, and many are still unemployed (New York Times, 2020). What is unique about nurses is that they are frontline caregivers, who necessarily must care for themselves and their family members as well as caring for patients. Unfortunately, this caring responsibility comes with more exposure risks to COVID-19 for nurses than the general public.

Limitations

The limitations to this study were the purposive sample, drawn from specific eligibility criteria for awarding the grant. Therefore, the results are not generalizable to the U.S. nurse workforce population. In addition, there is a lack of demographic information about ethnicity in the data from this study. The process to award this grant was based on the existing organizational rationale that ethnicity does impact the distribution of grants, and thus Nurses House, Inc. does not request that data on grant applications. Nurses House, Inc. utilized that same procedural approach to implement the COVID-19 grant.

Conclusion: Implications for Practice

Nurses remain at the forefront of healthcare delivery in the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Working in this environment has put nurses at risk for negative financial outcomes. This descriptive study provides an increased understanding about the financial distress that nurses have suffered thus far because of the impact of COVID-19. These data are consistent with the ANF (2020) findings regarding the financial impact of COVID-19 on nurses. However, the nurses in the ANF study dealt with their financial issues by other means. Those nurses delayed purchase/expenditures (42%), utilized saving/emergency funds (39%), used credits cards (32%), and reduced services/monthly payments (25%).

The nurses in this study also had financial distress but were resourceful in identifying the Nurses House, Inc. COVID-19 emergency fund as a financial safety net. While not asked how the grant money was used, thank you notes received from grantees indicated that the monies they received were used to pay their bills.

What is evident from this study is that there is no comprehensive financial safety net for nurses.What is evident from this study is that there is no comprehensive financial safety net for nurses. While increased understanding of this issue does not promise prevention or intervention, awareness of nurses at financial risk is important. Going forward, national policy initiatives that address lack of a financial safety net for healthcare workers on the frontline must be developed. An emergency funder like Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) needs to be created to concretely support our healthcare heroes who risk their own health and safety by providing care to others in their place of employment and at home.

The financial distress experienced by the group of nurses who were awarded emergency grants from Nurses House, Inc. due to suffering economic disruption from the COVID-19 pandemic can be a call to action. Advocacy to bring about an effective economic safety net, address child-care issues, equitable workmen’s compensation, and gender equity in salary would result in positive outcomes fostering social justice for nurses.

Assistance received from Nurses House, Inc. was interpreted by those nurses caring for others as an act of caring for themselves.In this year of the nurse, the ANA (2020) has acknowledged that nurses need to care for themselves before they can care for others. It is important to note that there is limited nursing research regarding self-care by nurses. However, the “Healthy Nurse, Healthy Nation” survey revealed that 68% of nurses put patient safety, wellness, and health before their own (ANA, 2017). Assistance received from Nurses House, Inc. was interpreted by those nurses caring for others as an act of caring for themselves. The work of Nurses House, Inc. and ANF described in this article is an exemplar of nurses caring for nurses. The question is, how can this exemplary work be expanded?

Acknowledgment: The authors of this study included the Director of Nurses House, Inc and two authors who serve on its board. There was no financial compensation to them for the sponsorship of this article.

Authors

Linda Millenbach, Ph.D, RN

Email: lmillenbach@icloud.com

Dr. Millenbach is the On-Site Director of the RN BS program at the School of Public Health at UAlbany in Albany, NY. She obtained her Bachelor’s and Master’s in Nursing from Russell Sage College in Troy, NY and her Ph.D from Adelphi University in Garden City, NY. She has held positions as a clinical nurse specialist, hospital administration and chair for a nursing education programs. Her interests are education, research, leadership and innovation.

Frances E. Crosby, Ed.D, RN

Email: fcrosby@niagara.edu

Dr. Crosby has a BS in Nursing from Niagara University, a MS in Child Psychiatric Nursing from Boston University and an Ed.D. from State University of NY at Buffalo. She has been a nurse researcher and educator, currently is the Assistant to the Provost for Nursing Education at Niagara University.

Jerome Niyirora, Ph.D, MS, RHIA

Email: ndayisj@sunypoly.edu

Dr. Niyirora is an associate professor in the Health Information Management program, part of the College of Health Science at SUNY Polytechnic Institute. Jerome’s doctoral training is in Systems Science from SUNY Binghamton. Jerome is also a registered health information administrator (RHIA). His research of interest involves integrating systems science models and machine learning techniques into the analytics and optimal healthcare systems design.

Kathleen Sellers, PhD, RN

Email: sellerk@sunypoly.edu

Dr. Sellers is a Clinical Associate Professor and Coordinator of the MS in Transformational Leadership Program at SUNY Polytechnic. She has numerous publications that focus on different aspects of nursing professional practice and presents regularly on these issues. She is a member of several professional nursing organizations including the NY Organization of Nurse Leaders and the Foundation of NYS Center for Nursing Research where she has served as Chair. She earned her bachelors from Niagara University, a graduate degree in nursing from The Catholic University of America and her PhD from Adelphi University.

Rhonda Maneval, DEd, RN

Email: rmaneval@pace.edu

Dr. Rhonda Maneval the Senior Associate Dean and Professor in the College of Health Professions and the Lienhard School of Nursing at Pace University. She is an experienced educator and academic administrator, currently teaching PhD students and supervising dissertation research. Her scholarship and expertise is in curriculum development and evaluation, interprofessional communication, including writing genre, and feminist approaches to qualitative research. Her current research focuses on two major areas: 1) the experience of stroke for survivors and caregivers in Ghana, and 2) strategies that influence the development of interprofessional practice competencies in healthcare providers. Both areas have an international focus that encompasses collaboration with researchers and faculty from other countries.

Jen Pettis, MS, RN, CNE, WCC

Email: jp5425@nyu.edu

Jennifer Pettis, MS, RN, CNE, WCC is the acting director of programs for Nurses Improving Care for Healthsystem Elders (NICHE) at the NYU Rory Meyers College of Nursing. In her role, Jennifer oversees the NICHE curriculum and programming ensuring that the clinical education content and materials are consistent with national standards and enhance current strategy and goals. Additionally, she supports the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) as a subject matter expert in nursing home resident assessment. Jennifer earned her MS in nursing education and BS in health care management from State University of New York (SUNY) Empire State College (ESC), where she serves as an adjunct faculty member, and her AAS in nursing from SUNY Adirondack.

Noreen B. Brennan, PhD, RN-BC, NEA-BC

Email: brennann1@nychhc.org

Dr. Brennan is the Chief Nursing Officer at NYC H+H/Metropolitan in New York City and hold dual board certification in Medical/Surgical Nursing and Nursing Leadership Advanced from ANCC. She is a member of adjunct faculty at Pace University, New York. Dr. Brennan is currently a member of the Boards of Nurses House and NYU nursing alumni.

Mary Anne Gallagher, DNP, RN, Ped-BC

Email: mag9383@nyp.org

Dr. Gallagher is the Director of Nursing for the Center for Professional Nursing Practice at NewYork-Presbyterian and Adjunct Faculty at Adelphi University. Dr. Gallagher is the Board of Directors secretary for Nurses House, Inc

Nancy Michela, DAHS, MS, RN

Email: michen@sage.edu

Dr. Michela is an Associate Professor of Nursing at Russell Sage College, Troy, NY. She served as Chair of the Public Education Committee at the Foundation of the NY State Nurses Association.

Deborah Elliott, MBA, BSN, RN

Email: delliott@cfnny.org

Deborah Elliott is the Executive Director of the Center for Nursing at the Foundation of NYS Nurses, Inc. and the Executive Director of Nurses House, Inc. She holds a Master’s in Business in Healthcare Administration from Union College, Schenectady, NY and a Bachelor’s in Nursing from the State University of New York at New Paltz. Deborah has held various leadership positions since becoming licensed as an RN in 1979 including the Director of OB/GYN and Pediatrics at St. Clare’s Hospital in Schenectady, NY and the Deputy Executive Officer of the New York State Nurses Association.

References

Ackerman, L. (2019). Caring science education: Measuring nurses’ caring behaviors. International Journal of Caring Science, 12(1), 572-583. Retrieved from: http://www.internationaljournalofcaringsciences.org/docs/64_ackerman_12_1.pdf

Adams, L. Y. (2016). The conundrum of caring in nursing. International Journal of Caring Science, 9(1), 1-8. Retrieved from: http://internationaljournalofcaringsciences.org/docs/1_1-Adams_special_9_1.pdf

American Journal of Managed Care. (2021). A timeline of COVID-19 developments in 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.ajmc.com/view/a-timeline-of-covid19-developments-in-2020

American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. Nursebooks.org. Retrieved from: https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/ethics/code-of-ethics-for-nurses/coe-view-only/

American Nurses Association. (2017). Executive summary: American Nurses Association health risk appraisal. Retrieved from: https://www.nursingworld.org/~4aeeeb/globalassets/practiceandpolicy/work-environment/health--safety/ana-healthriskappraisalsummary_2013-2016.pdf

American Nurses Association. (2020). COVID-19 resource center. Retrieved from: https://www.nursingworld.org/coronavirus

American Nurses Foundation. (2020). Pulse on the nation’s nurses COVID-19 survey series: Financial. ANA Enterprise. Retrieved from: https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/work-environment/health-safety/disaster-preparedness/coronavirus/what-you-need-to-know/financial-impact-survey/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, January 5). Things to know about the COVID-19 pandemic. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/your-health/need-to-know.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). United States COVID-19 cases and deaths by state. Retrieved from: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#cases_casesper100klast7days

Dague, S., Elliott, D., & Jorgensen, B. (2020). Nurses house provides relief to nurses affected by COVID-19. ANA – New York Nurse, 5(1), 9. Retrieved from: https://assets.nursingald.com/uploads/publication/pdf/2095/New_York_Nurse_7_20.pdf

Dong, Y., Mo, X., Hu, Y., Qi, X., Jiang, F., Jiang, Z., & Tong, S. (2020). Epidemiology of COVID-19 among children in China. Pediatrics, 145(6), e20200702. doi:10.1542/peds.2020.0702

Gallagher-Lepak, S., & Kubsch, S. (2009). Transpersonal caring: A nursing practice guideline.Holistic Nursing Practice, 23(3), 171-182. doi: 10.1097/HNP.0b013e3181a056d9

Garman, E. T., & Sorhaindo, B. (2005). Delphi study of experts’ rankings of personal finance concepts important in the development of the in charge financial distress/financial well-being scale. Consumer Interest Annual, 51, 184-194. Retrieved from: https://acci.memberclicks.net/assets/docs/CIA/CIA2005/garman_delphistudyofexpertsrankingsofpersonalfinanceconcept.pdf

Hayes, A. (2021, April 18). Financial distress. Investopedia. Retrieved from: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/f/financial_distress.asp

Kashen, J., Glynn, S. J., & Novello, A. (2020, October 30). How COVID-19 sent women’s workforce progress backward. Center for American Progress. Retrieved from: https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/women/reports/2020/10/30/492582/covid-19-sent-womens-workforce-progress-backward/

Lai, C. C., Shih, T. P., Ko, W. C., Tang, H. J., & Hsueb, P. R. (2020). Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): The epidemic and the challenges. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, 55(3), 05924. doi: 10.1016/ijantimicag.2020.105924

Leung, C. (2020). Risk factors for predicting mortality in elderly patients with COVID-19: A review of clinical data in China. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development, 188, 111255. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2020.111255

Menni, C., Valdes, A. M., Freydin, M. B., Ganesh, S., Moustafa, J. E. S., Visconti, A., Hyst, P. Bowyer, R., Mangino, M., Falchi, M., Wolf, J., Steves, C., & Specter, T. (2020). Loss of smell and taste in combination with other symptoms is a strong predictor of COVID-19 infection. medRxiv doi: 10.1101/2020.04.05.20048421

National Public Radio, Robert Woods Johnson Foundation, & Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health. (2020, September). The impact of coronavirus on households in major U.S. cities. Retrieved from: https://media.npr.org/assets/img/2020/09/08/cities-report-090920-final.pdf

New York Times. (2020, October 23). Out of work in America. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/10/22/us/pandemic-unemployment-covid.html

Nightingale, F. (1859). Notes on nursing: What it is and what it is not. Harrison. Retrieved from: https://archive.org/details/notesonnursingnigh00nigh

Nurses House. (n.d.). About us. Retrieved from: https://pages.nurseshouse.org/history

Nurse.com (2020). 2020 Nurse salary research report. Retrieved from: https://wp.nurse.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Nurse.com_Nurse_Salary_Research_Report_2020.pdf

Skretkowicz, V., & Nightingale, F. (1992). Florence Nightingale's notes on nursing. Scutari Press

Smiley, R. A., Lauer, P., Bienemy, C., Berg, J. G., Shireman, E., Reneau, K. A., & Alexander, M. (2019, January). The 2017 national nursing workforce survey. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 9(3), S1-S88. Retrieved from: https://www.journalofnursingregulation.com/action/showPdf?pii=S2155-8256%2818%2930131-5

Streeter, J. L., & Deevy, M. (2019, April 24). Financial security and the gender gap. Stanford Center on Longevity. Retrieved from: https://longevity.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Financial-Security-and-the-Gender-Gap.pdf

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2020, September 1), Occupational outlook handbook, Registered Nurses. U.S. Department of Labor. Retrieved from: https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/registered-nurses.htm

Watson J. (1979). Nursing: The philosophy and science of caring. Little Brown & Co.

Watson J. (1985). Nursing: Human science and human care. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Watson, J. (2007). Watson’s theory of human caring and subjective living experiences: Carative factors/caritas processes as a disciplinary guide to the professional nursing practice. Texto & Contexto – Enfermagem, 16(1). Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-07072007000100016

Watson, J. & Smith, M. (2002). Caring science and the science of unitary human beings: a trans'theoretical discourse for nursing knowledge development. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 37(5), 452-461. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02112.x

World Health Organization. (2021). Year of the nurse and the midwife 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/campaigns/annual-theme/year-of-the-nurse-and-the-midwife-2020