The rapid spread of coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) severely threatens human health worldwide. While many recent studies examining the COVID-19 pandemic have focused on service delivery and disease epidemiology, few have explored the lived experiences of frontline nurses caring for patients in the intensive care unit (ICU). In this study, we describe the lived experiences of nurses caring for patients with COVID-19 in the ICU during the COVID-19 pandemic. A qualitative research study using a phenomenological approach was conducted between May and September 2020. Eight ICU nurses were interviewed via phone calls.

The data were collected through semi-structured interviews based on an interview guide. Qualitative content analysis using Colaizzi's 7-step method was performed. Four themes related to caring for COVID-19 patients were revealed: 1) distress, 2) clinical incompetency, 3) challenges in patient care, and 4) resiliency. ICU nurses caring for patients with COVID-19 experienced physical, psychological, and moral distress in very challenging professional and environmental conditions. Understanding these experiences can contribute to developing strategies and policies to enhance nursing care beyond the COVID-19 pandemic.

Key Words: Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), pandemic, nurses' experiences, ICU, critically ill patients

Introduction

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is an infectious disease that can cause severe acute inflammatory respiratory syndrome.Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‑CoV‑2) causes COVID-19 (World Health Organization [WHO], 2020a). Most patients with the COVID-19 virus experience mild to moderate respiratory illness and recover without special treatment. Those with underlying disease and comorbidity are the most severely affected, requiring hospitalization and intensive care (WHO, 2020a). The outbreak of COVID-19 wreaked havoc around the world, with confirmed cases exceeding 606 million (deaths more than 6 million) as of September 2022 (WHO, 2022b). In the Eastern Mediterranean region, morbidity and mortality reached more than 23 million confirmed cases and more than 348,000 deaths, respectively (WHO, 2022c). More than 515,000 confirmed cases and more than 24,000 deaths were in Egypt as of September 2022 (WHO, 2022d).

COVID-19 patients with severe signs are directed to the hospital for medical treatment in the ICU. These intensive care units are often under strict isolation during epidemics and provide exceptional care for treating patients with COVID-19 (Shang et al., 2020). Isolation due to hospitalization for COVID-19 can last more than two weeks, and prolonged isolation represents a threat to care for patients and healthcare workers (Center for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2020a).

Nurses are essential in managing COVID-19 due to their crucial connection between patients and the broader healthcare team. They must ensure that all patients receive personalized, high-quality services, regardless of their infectious condition. Additionally, nurses plan for anticipated COVID–19–related outbreaks, which increase the demand for nursing and healthcare services and may strain the systems Nurses are essential in managing COVID-19 due to their crucial connection between patients and the broader healthcare team. (Jackson et al., 2020). Through careful observation of their patients, thorough assessment, and critical thinking, nurses notice subtle changes in patient conditions that indicate either deterioration or recovery (Jackson et al., 2020; Fawaz, Anshasi & Samaha, 2020). Thus, they anticipate the human response to medical issues over time, including the challenges posed by the COVID-19 crisis. This crisis presents numerous complex challenges to nurses' work routines, relationships with patients, and personal lives and fosters new respect and appreciation from the public for their dedication and sacrifices. Clarifying nurses' perception of caring for patients with COVID-19 may aid in improving and promoting patients' health (Galehdar, Toulabi, Kamran, Heydari, 2021).

Qualitative research methods are often used to explore the meanings of social phenomena in-depth as experienced by individuals in their natural context (Polit& Beck, 2020). A qualitative approach will lead to a better understanding of nurses' experience in caring for patients with COVID-19 disease. Knowledge regarding Egyptian ICU nurses' experiences of caring for COVID-19 is lacking. Such knowledge could provide evidence for increased support for nurses caring for COVID-19 patients and a higher standard of practice. Therefore, the current study aims to describe the lived experiences of nurses caring for critically ill patients with COVID-19 and enhance the caring service during such pandemics.

Methods

A phenomenological approach was used to describe and interpret the meaning of the lived experiences of nurses caring for critically ill patients with COVID-19. The phenomenological approach involves studying experience from the individual's perspective, 'bracketing' taken-for-granted assumptions, and usual ways of perceiving. This approach was chosen because little is known about the views and experiences of Egyptian ICU nurses caring for critically ill patients with COVID-19. The study was conducted in the ICU of an isolation hospital in Egypt. The ICU provides treatment for medical and surgical problems that require facilities for intra-arterial blood pressure monitoring, hemodynamic physiological parameters monitoring, mechanical ventilation, and COVID-19 care.

The purposeful sample was chosen to recruit nurses. Purposeful sampling involves identifying and selecting individuals or groups incredibly knowledgeable about or experienced with a phenomenon of interest (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2011). Nurses working for more than six months and providing direct clinical care for COVID-19 patients were eligible to participate in this study. The researchers recruited nurses experienced in caring for COVID-19 patients who could communicate experiences and opinions in an articulate, expressive, and reflective manner and were willing to participate in this study. Eight ICU nurses met the inclusion criteria and participated in this study. Seven males and one female participated in this study. The average age of participants was 23 years (range of 21–27 years). The average length of experience working in the ICU was two years (range:1 to 3 years). Only two participants had a baccalaureate degree in nursing.

Data collection

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) by the University Ethical Research Committee and the data collection hospital. Before participation, a detailed description of the study's nature, objectives, and methods was given. Oral informed consent was obtained if participants agreed to volunteer in this study. Furthermore, participants were assured that they could withdraw from the study. Data were collected from May to July 2020 through individual in-depth interviews using a semi-structured interview guide. The interview guide comprised seven open-ended questions encouraging participants to share their experiences (Table 1). Researchers developed the questions after reviewing the literature and obtaining expert opinions. Participants were asked to describe their experiences caring for COVID-19 patients in the ICU.

Table 1. The interview guide.

| Questions |

|---|

|

1. Please tell me what you felt/thought when caring for COVID-19 patients? |

|

2. How have your feelings changed from the first day you cared for COVID-19 patients until now? |

|

3. Do you think you have the necessary knowledge and skills to care for COVID-19 patients? Why? Why not? |

|

4. What or who offers you the most support when caring for COVID-19 patients? |

|

5. What challenges did you face when caring for COVID-19 patients? Have the challenges changed since you first started caring for COVID-19 patients? |

|

6. How does your experience in caring for COVID-19 patients compare to non-COVID-19 patients? |

|

7. How has caring for COVID-19 patients influenced or changed your nursing practice? |

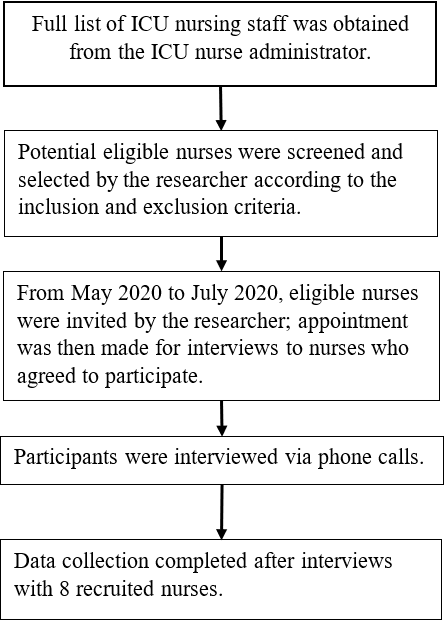

Interviews were conducted by phone due to hospital restrictions and reduced potential risks for transmission of COVID-19 to other individuals. The researcher conducted the interviews and had prior interview experience. All interviews ranged between 45 to 60 minutes. Interviews were conducted until data saturation was reached. To minimize bias, the researcher had no managerial relationship with any participants. All interviews took place in a quiet, private setting, with both the researcher and participants using headphones instead of a phone speaker to maintain confidentiality. The interviews were recorded by the researcher with the permission of the participants. Recorded data was transferred from the recording device to a password-protected folder in the encrypted computer. Figure 1 demonstrates the flowchart of the recruitment and data collection procedure.

Figure 1. Flowchart of recruitment and data collection procedure.

Data analysis

Interviews were analyzed using qualitative analysis according to Colaizzi's phenomenological analysis method. Colaizzi's method uses seven steps as follows: (1) collecting the participants' descriptions, (2) understanding the depth of the meanings, (3) extracting the essential sentences, (4) conceptualizing important themes, (5) categorizing the concepts and topics, (6) constructing comprehensive descriptions of the issues examined, and (7) validating the data following the four criteria set out by Lincoln and Guba (Colaizzi, 1978). Phone interviews were recorded, and the content was transcribed and re-read to gain a general and in-depth understanding of the participant's statements. This was followed by extracting the essential explanations and giving them specific concepts to conceptualize essential themes. The concepts were placed in specific categories, and findings were validated based on Lincoln & Guba's criteria (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Participants were informed that their names were blinded, and the research team assigned numbers to each interview to analyze the data.

Rigor

The Lincoln & Guba criteria were utilized to establish this study's rigor, including credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. Each participant voluntarily participated in the study. The interviewer, who had no personal or managerial relation with participants, encouraged participants to be honest, clarifying that there were no right or wrong answers to each question; this ensured the credibility of the interviews. Dependability was established by using a semi-structured interview guide to ensure consistency. Transferability was maintained by providing detailed descriptions and verbatim quotes, allowing readers to conclude whether the findings in the present study are transferable to their settings. One researcher completed the interview process to achieve confirmability, and all researchers independently and actively participated in the data analysis process.

Findings

Four common themes emerged from the thematic analysis, described below, along with selected samples of the respondents' supporting statements. The collection of the four themes articulates the lived experience of the ICU nurses during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Theme 1: Distress

This theme explores nurses' experiences of distress while caring for suspected and confirmed COVID-19 patients. During the peak of the pandemic, most participants reported significant distress, which was further categorized into three subthemes: physical, emotional, and moral distress.

The collection of the four themes articulates the lived experience of the ICU nurses during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Physical distress. Wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) was an unpleasant feeling ICU nurses experienced. Most nurses stated that wearing a heavy suit and donning multiple layers of personal protective equipment (PPE) for hours leads to bruises on the body, fainting from low blood sugar, fatigue, oxygen restrictions, and physical exhaustion. Moreover, nurses have struggled with fogging glasses due to wearing a face mask for long hours. Additionally, applying and removing PPE were considered highly time-consuming for nurses, particularly when requiring supplies or performing duties outside the isolation room.

"It is exhausting, the fatigue, the pressure of prolonged wearing of the equipment, is challenging, and you are sweating." (Participant 4)

"The problem with a face mask is fogging, and I cannot see well while providing care for patients." (Participant 5).

Mental distress. ICU nurses experienced mental distress while caring for COVID-19 patients. All participants experienced a fear of infecting family members, anxiety about assuming new or unfamiliar clinical roles, and grief. All participants feared the disease itself as it is a new disease and the possibility that they may contract it and become sick. One of the participants said,

"I am always afraid that I will easily get infected" (Participant 1)

This fear of a new disease amongst nurses also extended to fear for their family's safety and risk of COVID-19 infection transmission. Nurses were afraid of infecting their family members with COVID-19 from workplace exposures, especially loved ones who are pregnant, older, and chronically ill.

"I was terrified about what would happen to me if I did have COVID-19." (Participant 3)

"I think of my pregnant wife, and I feel guilty if I have work-related exposure and infection and infect her." (Participant 4)

"I felt stressed when I saw the first case of COVID-19 because I was assigned for the first time, but I was fine the second time I cared for a COVID-19 patient." (Participant 5)

"I felt anxious about making errors while donning on and off my PPE." (Participant 8)

It is noted that anxiety about assuming new or unfamiliar clinical roles and expanded workloads while caring for patients with COVID-19 was another contributing factor to the nurses' fear. Additionally, nurses expressed grief while caring for growing numbers of acutely ill COVID-19 patients who can deteriorate rapidly in the ICU.

"When I entered the isolation room, I worried. I felt much better after I got used to it." (Participant 3)

"The matter becomes worse when my patients were stable and suddenly went into cardiac arrest or died from COVID-19 while I was caring for them." (Participant 5)

"I do not know what exactly happened for many cases, as they suddenly became deteriorated; however, they looked all right before their sudden death" (Participant 1)

Moral distress. ICU nurses are already faced with difficult ethical decisions of prioritizing ICU care and ventilator support for patients with a higher chance of survival. Nurses noted that the difficulties and moral involvement with patients with COVID-19 in the ICU had challenged their practice of principles of genuine nursing care and decreased their compassion satisfaction. Nurses also felt guilty, frustrated, and powerless when they could not practice according to their ethical standards. While their patients are suffering from severe health conditions caused by COVID-19, they implemented a decision to deny or delay treatment contrary to their profession's standards and norms about saving lives and relieving suffering.

Furthermore, ICU nurses experience negative emotional consequences while caring for their colleagues and witnessing their deaths. This can further add to their moral distress and increase the risk of burnout and attrition. The nurses discussed the experience of long shifts, isolation, and quarantine practices in the hospital, affecting their job performance.

"You see patients are suffering, clinically deteriorated, and providing end-of-life care for patients dying without family physically present. It is stressful situations we may not have encountered before." (Participant 7)

"We never expected to think of our safety before initiating chest compressions on a pulseless patient. Yet, the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic." (Participant 4)

Theme 2: Clinical incompetence

Care of patients with COVID-19 is complex and requires specialized, supportive care, especially nursing expertise, knowledge, attitude, and skills. The COVID-19 pandemic has underlined the need for advanced nursing skills in managing ventilators, symptom control, and essential communication with families and teams because of the patients' rapidly changing conditions. However, nurses applied the ever-changing and most up-to-date guidelines, accessed many resources, and followed many valid websites to improve their knowledge and skills. Nurses perceived their knowledge and skills as inadequate, highlighting their need for more training and education in managing crises involving clinical treatment of critically ill patients with COVID-19, decontamination, isolation, communication, triaging, psychological support, and infection control.

"When I completed the infection control training (proper use of PPE), I became more comfortable caring for COVID-19 patients." (Participant 6)

"My experience and knowledge increased in caring for patients with respiratory problems, respiratory failure, and using mechanical ventilators effectively." (Participant 7)

"We are learning about the virus, and we are following the latest information, treatment, and management strategies, but we still need further training" (Participant 1)

"We clustered care of standard procedures such as central venous catheter and arterial lines to minimize the frequency of exposure to COVID-19." (Participant 4)

Nurses reported that they were not competent in delivering palliative care before the COVID-19 crisis and could only rely on their past experiences to guide them in palliative care for COVID-19 patients. Additionally, they felt this sense of urgency to hone their clinical competency while providing palliative care in the ICU to support patients, caregivers, and themselves. The nurses identified other measures that would have made it easier for them to integrate palliative and end-of-life care principles in the ICU. Many nurses suggested that all ICU staff (nursing, medical, and allied health) complete a palliative care course with yearly refresher courses to ensure everyone is familiar with palliative care interventions at the ICU.

"We do not have specific knowledge and training in implementing palliative and end-of-life care for patients with COVID-19" (Participant 1)

"Incorporating palliative is crucial to support healthcare providers dealing with daily losses, family caregivers, and ourselves." (Participant 3)

Theme 3: Challenges in patients' care

Patient care is a priority in nursing practice, and providing care for COVID-19 patients was very difficult. ICU nurses face many challenges in patient care. Performing high-risk aerosol-generating procedures is a significant challenge that affected ICU nurses' practice during the pandemic.

These procedures are standard because critically ill COVID-19 patients need suctioning, intubation, or extubating. Aerosol-generating procedures include endotracheal intubation, airway suctioning, nebulizer treatment, manual ventilation before intubation, chest physiotherapy, tracheostomy, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation. The nurses feared that the airway's viral load was very high and contagious, posing significant risks for those who perform airway suction, intubation, and extubation.

"Endotracheal intubation and extubating are frequently associated with some coughing; it is considered an aerosol-generating procedure and puts us at high risk for COVID-19 infection." (Participant 1)

Maintaining nurses' safety during cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) for patients with COVID-19 is very challenging as it may require prolonged time in COVID-19 patients compared to non-COVID-19 patients. Furthermore, CPR requires all team members to wear appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE). The donning of the PPE frequently delayed resuscitation success because of the delayed response to initiate CPR. Also, prolonged exposure to the patient increases the chances of infection for the healthcare team.

"CPR for the patient with COVID-19 is exhausting, and sometimes takes 20 minutes or more, and this long time may increase the risk of viral transmission for members of the CPR team." (Participant 5)

"It is challenging to delay treatment, saving lives, and relieving suffering while waiting for donning PPE." (Participant 2)

ICU nurses also reported that communication was difficult while wearing PPE. Wearing PPE could muffle voices and conceal non-verbal cues; this was worsened if patients were supported by continuous positive airway pressure machines or high-flow oxygen.

"PPE impedes communication between patients and healthcare providers, you cannot hear them, and they cannot see you through the visor." (Participant 5)

Another challenge reported by ICU nurses was the language barrier between patients and nurses. Nurses stated that many patients from various nationalities were admitted to the isolation hospital and were not fluent in English or Arabic. There were no interpreters available, which added an extra burden on nurses and affected the quality of care and patient safety.

"Language barriers can hinder the patient's assessment and family's understanding of COVID-19, especially if the disease has any specific meaning for them or if there are specific treatments that align with cultural traditions." (Participant 3)

Them 4: Resiliency

The demand and increasing illness severity from critically ill patients required nurses to work with a response team with different job requirements. During the pandemic, most ICU nurses felt that a high level of resilience was maintained. Nurses said they could provide care and cope with this crisis despite numerous challenges and circumstances, such as lack of equipment, long shifts, fear, uncertainty, and inexperience. Moreover, nurses viewed working during difficult times and in dangerous situations as a part of their role and professional obligation, requiring them to be resilient. One participant noted

– "Regardless of the workload and challenges we faced; we can deliver care with compassion during a high contagious disease." (Participant 2)

One of the significant factors influencing nurses' resilience during the pandemic was the emotional and psychological support from the medical and nursing management, family members, and community members. The team took extra measures to ensure the staff felt appreciated and recognized for their hard work. This involved providing food and also messages of thanks. Many respondents reported that these tokens were greatly appreciated and contributed to the team atmosphere.

"People in the community provide frequent support, encouragement, and this created a good feeling in me." (Participant 8).

"The team got much closer because we worked hard, and everybody should get credit for that."

Discussion

This study explored the lived experiences of ICU nurses caring for patients with COVID-19 during the highest phase of the pandemic at an isolation hospital in Egypt. The main themes emerging from the nurses' statements were distress (physical, psychological, and moral), clinical incompetency, challenges in patient care, and resiliency while caring for COVID-19.

This study's first central theme was distress (physical, psychological, and moral distress). The participants in this study reported physical distress due to workload, long shifts, and critical condition of patients. The experiences reported by ICU nurses in this study mirror reports from other countries. Kackin et al. (2020) reported that caring for COVID-19 patients puts a heavy physical burden on nurses in Turkey. Liu et al. (2020) also confirmed that caring for patients for long hours while wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) leads to nurses' physical distress. The findings are also consistent with the previous studies and demonstrate that healthcare professionals react with fear for their safety during human swine influenza (HIS), Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and the Ebola virus (Lam & Hung, 2013; Bukhari et al., 2016; Koh et al., 2012; Speroni et al., 2015).

It was expected that nurses experienced anxiety about their health while caring for COVID-19 patients during a pandemic. This study showed that all participants experienced psychological symptoms such as fear, anxiety, and grief. These experiences may cause secondary traumatic stress and compassion fatigue among nurses and can reduce the quality of patient care. Similarly, Karami et al. (2020) reported fear, anxiety, and worry in the lived experiences of nurses caring for patients with COVID-19 in Iran. They emphasized that nurses working in the wards and care centers dedicated to COVID-19 patients experience poor mental, emotional, and occupational conditions, jeopardizing quality care. Sun et al. (2020) attributed fear, anxiety, and worry to uncertainty about the source of the virus, lack of specific treatment, high infection rate, a high mortality rate among healthcare workers, and fear of infection in nurses. Also, Zhang et al. (2020) reported that nurses' fear, anxiety, and worry are feelings of uncertainty about the COVID-19 situation. They stated that these negative psychological feelings could lead to nurses' stress or vulnerability.

The experiences reported by ICU nurses in this study are similar to those of the Gordon et al. (2021) study; nurses experienced moral distress and emotional exhaustion in the care environment due to the inability to provide comforting human connections, experiencing patient deaths, isolation, and care delays. In our study, nurses experienced moral distress and emotional exhaustion due to severe conditions caused by COVID-19 and care delays. Patients died alone without family, which profoundly impacted nurses' psychological and spiritual well-being and resulted in compassion fatigue. In this regard, Norman et al. (2021) reported high levels of moral distress in nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. They cite this as worries about COVID-19's negative impact on the family, fear of infecting others, and work-related concerns.

Nurses must be well-equipped with essential knowledge and skills to manage crises involving clinical treatment, decontamination, isolation, communication, triaging, psychological support, and palliative care. The participants in this study highlighted the need for training and developing their skills to increase their clinical competency in caring for critically ill COVID-19 patients. These findings coincide with a previous study by Al Thobaity et al. (2015); researchers found that nurses perceive themselves as unprepared and need more education and training in crisis management.

The intensive care approach and palliative care approach to patients with COVID-19 have several differences; many of these patients will end up dying in the ICU, and it is essential to integrate both practices in such patients. In this study, ICU nurses noted that they were incompetent in providing palliative care in the ICU and highlighted their need to receive training on effectively controlling symptoms such as dyspnea, pain, and delirium in patients who are candidates for ICU care and to maintain comfort at the end of life. These results are incongruent with the Chisbert-Alapont et al. (2021) study; the researchers noted that palliative care training is essential during the pandemic, not only for the acquisition of skills to deal with the emotions of facing death and the stress of both patients and families and the professionals themselves. Also, Rosa et al. (2020) highlighted the urgent need for palliative care integration throughout critical care settings to support critical care nurses in alleviating suffering during the COVID-2019 pandemic and strengthen nursing capacity to deliver high-quality, person-centered critical care.

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in patients with COVID-19 poses a unique challenge to nurses due to the risk of viral aerosolization, and prolonged exposure to the patient increases the chances of infection for the healthcare team. In the same line, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] (2020b) reported that healthcare providers accounted for up to 11% of reported cases of COVID-19 in some US states. Furthermore, tracheal intubation could carry the highest risk of viral aerosolization. Moreover, these findings were congruent with a prospective international multicenter cohort study by El‐Boghdadly et al. (2020). The researchers recruited 1,718 healthcare workers who performed or assisted in the tracheal intubation of patients with suspected or confirmed COVID‐19 across 17 countries. The results showed that approximately 10% of healthcare workers were either diagnosed with a new COVID‐19 infection or required self‐isolation or hospitalization with new symptoms following involvement in tracheal intubation of patients with suspected or confirmed COVID‐19.

Generally, wearing PPE was tolerated by most nurses as it was deemed necessary to protect them. However, the physical problems of wearing PPE for long periods were identified as challenging for nurses. Furthermore, donning and removing PPE was time-consuming for staff, mainly when performing life-saving procedures such as CPR, leading to care delays. Additionally, communication was difficult among nurses, their patients, and colleagues. Similar results were reported in the Iranians' study; nurses experienced extreme heat due to wearing protective clothing, thirst, skin problems due to excessive sweating and wearing a mask, difficulty going to the toilet, and strict compliance with protective protocols (Ahmadidarrehsima et al., 2021).

Despite challenges in caring for COVID-19 patients in the ICU, it was noted that nurses demonstrated resilience, responsibility, professional commitment, and strength.Communication with patients is essential to providing high-quality nursing care. The current study revealed that language barriers could affect nursing practice and patient safety. Non-English-speaking patients with COVID-19 can be subject to healthcare delays due to communication barriers with healthcare providers. Moreover, language barriers can result in miscommunication that impacts the patient's understanding of their condition and treatment. The study findings were supported by Gordon et al. (2021). The researchers reported that nurses face language barriers in the critical care environment, and requisite isolation further complicates translation tools for non-English speaking patients and family members.

Despite challenges in caring for COVID-19 patients in the ICU, it was noted that nurses demonstrated resilience, responsibility, professional commitment, and strength. However, their commitment created a strong sense of moral distress related to patients' suffering, loss, and sudden deaths; nurses could cope with their stress with minimal professional support. Working during difficult times and in dangerous situations was viewed by nurses as part of their role and their professional obligation. Zhang et al. (2020) found that nurses on the frontline fighting COVID-19 positively take measures to cope with stress, which is encouraging and indicates that most nurses adapted to the situation. These findings also align with a study conducted in China by Lui et al.(2020); the researchers reported that the healthcare providers experienced a high responsibility to their patients with COVID-19 to alleviate suffering. Lam et al. (2020) reported that nurses felt a great sense of professional duty to work during a pandemic regardless of the circumstances.

Limitations

Due to the restrictions of the isolation hospital during the coronavirus pandemic, it was not easy to find and directly interview participants for the study as ICU nurses were busy. However, the data collected were rich in content and corresponded to the aim of the study. Also, the results of this study are limited to interviews and reflect the working culture in Egyptian healthcare. Therefore, the investigators acknowledge that the findings pertain to ICU nurses caring for COVID-19 patients in Egypt.

Implications for practice

Healthcare organizations must recognize critical care nurses' experiences during and after the pandemic. The ICU is a high-stress environment, and caring for COVID-19 patients can cause acute stress. Healthcare leaders must engage in communication to understand nurses' concerns and experiences. Nurses must be provided with physical and emotional support, such as offering a psychiatric clinical specialist during and after a pandemic.

Hospital leaders must consider a healthy and safe working environment to empower their efforts to control and manage the outbreak. The work environment should be equipped with enough supplies and personal protective equipment. In addition, continuous training, monitoring, and appropriate infection control procedures should be provided to adapt to the sudden and extreme demands of caring for patients during a pandemic, especially in the ICU.

The COVID-19 pandemic surpassed the healthcare system's capacity and created a need to integrate palliative care into pandemic planning. In the ICU, nurses must be equipped with primary palliative care principles and skills in symptom management, communication, and spiritual care. Furthermore, increasing ICU engagement in palliative care during and after the COVID-19 pandemic may alleviate nurse distress, thus reducing burnout and compassion fatigue.

Policymakers must develop a plan for budgetary support for healthcare organizations during pandemics to provide additional supplies, staffing, and psychological support that may be needed. Further research should expand the understanding of factors influencing nurses' perception and quality during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusion

This study provides a detailed description of the perceptions of ICU nurses caring for critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Egypt. The nurses' experiences were explored, and their views were validated via critical examination and comparisons with previous research. This study revealed that ICU nurses caring for patients with COVID-19 experienced distress, clinical incompetence, care environment challenges, and resilience. There is a need for more support for nurses delivering patient care during a crisis such as a pandemic.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank the ICU nurses for their hard work and commitment during the pandemic and for participation in this study. Also, we would like to thank Dr. Dana Hansen for her review.

Authors

Mona Hebeshy, PhD, RN

Email: mhebeshy@kent.edu

ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5106-8046

Mona Hebeshy, PhD, RN, is an Assistant Professor in Suez Canal University Faculty of Nursing. She earned an MSN in Nursing from Suez Canal University and a Ph.D. in Nursing from Kent State University, Kent, Ohio, USA. She was a visiting scholar at Purdue University, Indiana, USA (2013-2015). Monda had over 15 years of experience and training in qualitative and quantitative research using various methods. She teaches graduate and undergraduate courses in critical care, medical-surgical nursing, and research methods at Suez Canal University.

Esraa Hassan, Ph.D

Email: Esraa_ahmed@nursing.suez.edu.eg

Esraa Hassan, Ph.D, is an Assistant Professor in Suez Canal University's Faculty of Nursing, where she earned her Ph.D. She teaches graduate and undergraduate critical care and medical-surgical nursing courses at Suez Canal University. She has over eight years of experience working in academia and clinical settings.

Samia Husseiny Gaballah, Ph.D

Email: samia_gaballah@nursing.suez.edu.eg

ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4756-2241

Samia Husseiny Gaballah, Ph.D, is an associate professor at Suez Canal University's Faculty of Nursing, Egypt. She was an assistant professor of critical care nursing at Princess Nora University, Saudi Arabia. Her areas of expertise include medical-surgical nursing, critical care nursing, and quantitative research methods.

Somaya Elsayed Abou Abdou, Ph.D

Email: Somaya_67@yahoo.ca

Somaya Elsayed Abou Abdou, Ph.D completed her Ph.D. in Psychiatric Nursing at the Faculty of Nursing, Suez Canal University, Egypt. She is an associate professor of psychiatric and mental health nursing. She is also one of the board members of the Faculty of Nursing at the same university. She has over 30 years of experience in psychiatric nursing and training in various research methods.

References

Ahmadidarrehsima, S., Salari, N., Dastyar, N., & Rafati, F. (2022). Exploring the experiences of nurses caring for patients with COVID-19: A qualitative study in Iran. BMC Nursing, 21(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-022-00805-5

Al Thobaity, A., Plummer, V., Innes, K., & Copnell, B. (2015). Perceptions of knowledge of disaster management among military and civilian nurses in Saudi Arabia. Australasian Emergency Nursing Journal: AENJ, 18(3), 156–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aenj.2015.03.001

Bukhari, E. E., Temsah, M. H., Aleyadhy, A. A., Alrabiaa, A. A., Alhboob, A. A., Jamal, A. A., & Binsaeed, A. A. (2016). Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) outbreak: Perceptions of risk and stress evaluation in nurses. Journal of Infection in Developing Countries, 10(8), 845–850. https://doi.org/10.3855/jidc.6925

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Characteristics of health care personnel with COVID-19 — United States. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(15), 1–4. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6915e6.htm#:~:text=Data%20completeness%20for%20HCP%20status,15%2C194)%20of%20all%20reported%20cases

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Duration of isolation and precautions for adults with COVID-19. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/duration-isolation.html

Chisbert-Alapont, E., García-Salvador, I., De La Ossa-Sendra, M. J., García-Navarro, E. B., & De La Rica-Escuín, M. (2021). Influence of palliative care training on nurses' attitudes towards end-of-life care during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11249. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111249

Colaizzi, P. F. (1978). Existential phenomenological alternatives for psychology. Oxford University Press.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed-method research (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

El-Boghdadly, K., Wong, D., Owen, R., Neuman, M. D., Pocock, S., Carlisle, J. B., Johnstone, C., Andruszkiewicz, P., Baker, P. A., Biccard, B. M., Bryson, G. L., Chan, M., Cheng, M. H., Chin, K. J., Coburn, M., Jonsson Fagerlund, M., Myatra, S. N., Myles, P. S., O'Sullivan, E., Pasin, L., … Ahmad, I. (2020). Risks to healthcare workers following tracheal intubation of patients with COVID-19: A prospective international multicenter cohort study. Anaesthesia, 75(11), 1437–1447. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15170

Fawaz, M., Anshasi, H., & Samaha, A. (2020). Nurses at the front line of COVID-19: Roles, responsibilities, risks, and rights. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 103(4), 1341–1342. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.20-0650

Galehdar, N., Toulabi, T., Kamran, A., & Heydari, H. (2020). Exploring nurses' perception of taking care of patients with coronavirus disease (COVID-19): A qualitative study. Nursing Open, 8(1), 171–179. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.616

Gordon, J. M., Magbee, T., & Yoder, L. H. (2021). The experiences of critical care nurses caring for patients with COVID-19 during the 2020 pandemic: A qualitative study. Applied Nursing Research, 59, 151418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2021.151418

Jackson, D., Bradbury-Jones, C., Baptiste, D., Gelling, L., Morin, K., Neville, S., & Smith, G. D. (2020). Life in the pandemic: Some reflections on nursing in the context of COVID-19. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(13-14), 2041–2043. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15257

Kackin, O., Ciydem, E., Aci, O. S., & Kutlu, F. Y. (2021). Experiences and psychosocial problems of nurses caring for patients diagnosed with COVID-19 in Turkey: A qualitative study. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 67(2), 158–167. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020942788

Karimi, Z., Fereidouni, Z., Behnammoghadam, M., Alimohammadi, N., Mousavizadeh, A., Salehi, T., Mirzaee, M. S., & Mirzaee, S. (2020). The lived experience of nurses caring for patients with COVID-19 in Iran: A phenomenological study. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 13, 1271–1278. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S258785

Koh, Y., Hegney, D., & Drury, V. (2012). Nurses' perceptions of risk from emerging respiratory infectious diseases: A Singapore study. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 18(2), 195–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-172X.2012.02018.x

Lam, K. K., & Hung, S. Y. (2013). Perceptions of emergency nurses during the human swine influenza outbreak: A qualitative study. International Emergency Nursing, 21(4), 240–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ienj.2012.08.008

Lam, S., Kwong, E., Hung, M., & Chien, W. T. (2020). Emergency nurses' perceptions regarding the risk appraisal of the threat of the emerging infectious disease situation in emergency departments. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 15(1), e1718468. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2020.1718468

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage Publications.

Liu, Q., Luo, D., Haase, J. E., Guo, Q., Wang, X. Q., Liu, S., Xia, L., Liu, Z., Yang, J., & Yang, B. X. (2020). The experiences of healthcare providers during the COVID-19 crisis in China: A qualitative study. The Lancet Global Health, 8(6), e790–e798. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30204-7

Norman, S. B., Feingold, J. H., Kaye-Kauderer, H., Kaplan, C. A., Hurtado, A., Kachadourian, L., Feder, A., Murrough, J. W., Charney, D., Southwick, S. M., Ripp, J., Peccoralo, L., & Pietrzak, R. H. (2021). Moral distress in frontline healthcare workers in the initial epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States: Relationship to PTSD symptoms, burnout, and psychosocial functioning. Depression and Anxiety, 38(10), 1007–1017. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.23205

Polit, D., & Beck, C. (2020). Essentials of nursing research: Appraising evidence for nursing practice (10th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Rosa, W. E., Ferrell, B. R., & Wiencek, C. (2020). Increasing critical care nurse engagement of palliative care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Critical Care Nurse, 40(6), e28–e36. https://doi.org/10.4037/ccn2020946

Shang, Y., Pan, C., Yang, X., Zhong, M., Shang, X., Wu, Z., Yu, Z., Zhang, W., Zhong, Q., Zheng, X., Sang, L., Jiang, L., Zhang, J., Xiong, W., Liu, J., & Chen, D. (2020). Management of critically ill patients with COVID-19 in ICU: A statement from frontline intensive care experts in Wuhan, China. Annals of Intensive Care, 10(1), 73. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-020-00689-1

Speroni, K. G., Seibert, D. J., & Mallinson, R. K. (2015). Nurses' perceptions on Ebola care in the United States, Part 2: A qualitative analysis. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 45(11), 544–550. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000000261

Sun, N., Wei, L., Shi, S., Jiao, D., Song, R., Ma, L., Wang, H., Wang, C., Wang, Z., You, Y., Liu, S., & Wang, H. (2020). A qualitative study on the psychological experience of caregivers of COVID-19 patients. American Journal of Infection Control, 48(6), 592–598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2020.03.018

World Health Organization. (2020). Coronavirus. https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus#tab=tab_1

World Health Organization. (2022). WHO coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/

World Health Organization. (2022). COVID-19 situation in WHO's Eastern Mediterranean Region. http://www.emro.who.int/health-topics/corona-virus/index.html

World Health Organization. (2022). COVID-19 situation in Egypt. https://covid19.who.int/region/emro/country/eg

World Health Organization. (2020). World Health Organization guidance for managing ethical issues in infectious disease outbreaks. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/250580

Zhang, Y., Wei, L., Li, H., Pan, Y., Wang, J., Li, Q., Wu, Q., & Wei, H. (2020). The psychological change process of frontline nurses caring for patients with COVID-19 during its outbreak. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 41(6), 525–530. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2020.1752865