The COVID-19 pandemic has been a wake-up call for many aspects of our daily lives. Nurse regulators have had to respond quickly to many of the challenges that the profession has faced. Some solutions have been formulated on sound evidence and represent an appropriate and rational response to what could be described as long-overdue change. Other solutions have been less than ideal and have functioned as a stopgap or trade-off between two or more less than ideal scenarios. In this article we begin with a brief synopsis of pandemics. We then describe the method, results and discussion, and limitations of our analysis of legislative changes pertinent to professional regulation. Our analysis and conclusions reflect on lessons learned, identify opportunities that should be consolidated into permanent change, and discuss issues that need to be addressed if we are to be better prepared for the next pandemic.

Key Words: COVID-19, coronavirus, pandemic, legislative reform, professional regulation, scope of practice, license portability

During the pandemic, these vulnerabilities have required urgent attention, creative problem solving, and rapid change. Charles Darwin noted that it is not the strongest of the species that survive, nor the most intelligent, but the most responsive to change (Darwin, 1859).Certainly, it can be said that the COVID-19 pandemic has been a wake-up call for many aspects of our daily lives. We may have taken these aspects for granted and, as a result, we have as individuals, professionals, and societies, now discovered a wide range of vulnerabilities. During the pandemic, these vulnerabilities have required urgent attention, creative problem solving, and rapid change. The solutions formulated in some cases were well evidenced and represented an appropriate and rational response that perhaps should have been implemented years ago.

Other solutions, in retrospect, were less than ideal and could be described as a stopgap or the best choice of two or more trade-off scenarios. As we reflect on what has happened and consider how we will consolidate the new reality with the old, careful analysis of these changes is needed. In short, we argue that there is a need to protect and codify those changes that served us well and offer advantage for the future. However, we also recognize the need to roll back those changes made of necessity but less than ideal in their implications on public safety and nursing regulation processes. In this case, we must acknowledge risk and concentrate on how we can formulate better solutions to deal with the same situations that will reoccur at some undetermined time in the future.

...careful analysis of these changes is neededHistorians, in subsequent work, will memorialize us as the first generation on this planet since the great Spanish-flu pandemic to face a globally cataclysmic event that is reshaping societies, economies, and healthcare delivery models. Critically, and we would argue appropriately, our generation should be measured by whether we are wise enough to accept that mistakes were made, reflect on lessons learned, and put in place responses that prepare the ground for increased capacity to deal with similar challenges that generations ahead will have to face.

A Brief Synopsis of Pandemics

The COVID-19 pandemic is... presents the world with a set of challenges that [we] faced on a recurring basis from the times of the middle agesThe COVID-19 pandemic is not a unique phenomenon and presents the world with a set of challenges that governments, societies, and health workers have faced on a recurring basis from the times of the middle ages (Madhav et al., 2018). Over the centuries, infections have included diseases such as bubonic plague, smallpox, cholera, various types of flu and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Each has presented both similar and, in some cases, novel challenges. However, in assessing the consequences of these events it is, according to Madhav et al. (2018), appropriate to consider four major dimensions: health, economic, social and political impacts.

Each of these dimensions is worthy of study and even within each of the four dimensions additional sub-analysis is important if we are to learn from both our successes and failures. Chan and Burkle (2013) undertook a comprehensive review of the literature on disasters and global health crises and proposed a framework and methodology to help navigate the major themes of scholarship on the topic; however, regulatory dimensions did not feature in this analysis. To address this gap, we focus on lessons learned and insights gained from a professional regulatory perspective while dealing with the emerging challenges presented by the COVID-19 pandemic.

This normal will be informed by triangulating the insights of experts with the hope that collectively we will implement better solutions for the next pandemic event that will occur.It is not our intention to examine the pre-cursors and the initial events that took us to this point but rather to focus on the tools used to address the challenges faced and how regulators have responded. To this end we look at federal, state, and to a lesser extent, local action. We also acknowledge that we are writing this in the midst of the pandemic response and we fully believe and acknowledge that our analysis should be viewed as a forerunner to work that will need to be forensically examined and augmented once the world has determined the new normal. This normal will be informed by triangulating the insights of experts with the hope that collectively we will implement better solutions for the next pandemic event that will occur. As Gostin (2004) succinctly stated in the wake of the SARS outbreak, “The threat... appears to be rising, yet global and national health programs are preparing only fitfully. There is no way to avoid the dilemmas posed by acting without scientific knowledge” (p. 565). Nurses must work together to surface our collective learning, share our insights, and plan for a more agile and effective response when we, or our successors, face the next pandemic.

Method

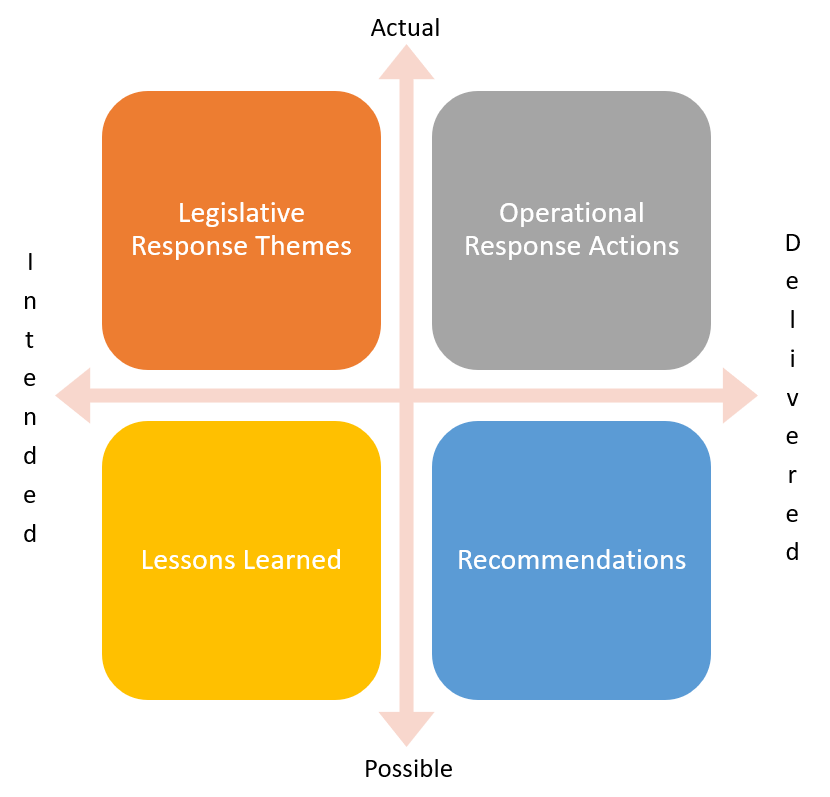

Our work is based upon a documentary analysis of legislative tools used to address actual and perceived barriers to the mobilization and delivery of care by healthcare practitioners. This analysis is augmented by insights gathered from requests for support from nurse regulatory bodies in the United States and Canada that were voiced in the first four months of 2020. To help bring order to our analysis we developed a simple analytical framework, Figure 1.

Figure 1. Analytical Framework to Examine the Nurse Regulatory Response to COVID-19

The framework supports the examination of the actual issues being addressed: the intended consequences of the legislative intervention; the operational response; and associated delivered consequences. Finally, through analysis of the lived experiences of the regulatory bodies we seek to capture lessons learned and make recommendations to provide a basis to handle future events in a more efficient, effective, and timely manner.

Emergency Powers: Source, Structure, and Intent

Most frontline nurses receive only a rudimentary understanding of how emergency legislative powers are formulated and enacted during their initial nursing education. Although it is not our intent to address this topic in detail, we believe it is important to provide a brief description of the various legislative tools than may be in force during a pandemic.

Preliminary action is taken to declare a state of emergency, triggering both federal and state measures.While the federal government plays a vital role in aiding states during times of disaster, the authority to manage a crisis rests with the state via the 10th amendment of the United States Constitution (Davis, 2020). Governors, as chief executives of their states, have authority over emergency management, including infectious diseases that cross jurisdictional borders. The centralization of power with the state executive office, versus the legislature, is reasoned due to the speed at which executive action can be taken (Trickey, 1965). The powers are outlined in state constitutions, though often codified and further defined and directed through state statute (Trickey, 1965). Preliminary action is taken to declare a state of emergency, triggering both federal and state measures.

During this pandemic, governors, having declared such a state of emergency, have then proceeded to address a wide range of issues that can impact the entire population of the state, such as the requirement to wear masks in public places. Other issues were more narrowly tailored to, or targeted, a specific service or group. For example, many states had an urgent need to facilitate the mobility of healthcare practitioners across state lines. This prompted various actions that ranged from authorizing the issuance of expedited and temporary licensure to waiving licensure requirements entirely.

...many states had an urgent need to facilitate the mobility of healthcare practitioners across state lines. By virtue of the unforeseen and sometimes unprecedented circumstances addressed by emergency actions, whether legislative or executive, these actions are time-limited by mandate or prescription. Frequently these orders are not universally welcomed. As a result, the actions will likely ignite a policy debate that extends past the conclusion of the emergency declarations. It is therefore important to be mindful of the changes as they are implemented so as to gather information about their impact if evidence is to be used to bring about a permanent post crisis shift in the regulatory environment.

Data Collection and Thematic Mapping

This study used documentary analysis, as described by Bowen (2009) to access and analyze the content of legislative documents, executive orders, proclamations, and bills, proposed and/or enacted during February to April 2020 in the United States at federal state or sub-state levels. We used both quantitative and qualitative analysis. The intent was to identify government actions that related to or had an impact on the role of nurse regulators and their mandate to protect the public. Broader issues, such as the availability of personal protective equipment (PPE), were not examined; this topic should be studied in further research.

We validated the data by triangulating the themes identified by the documentary analysis with board of nursing (BON) senior staff and their education and service partners dealing with the consequences of the various policy changes. To validate the emergent themes, six weekly, web-based events were organized from March 26 until April 30, 2020. Issues identified were presented and participants were asked to provide feedback and augment the list of themes with any other aspects of the legislation that they felt impacted the pursuit of their public protection mandate.

Results and Discussion

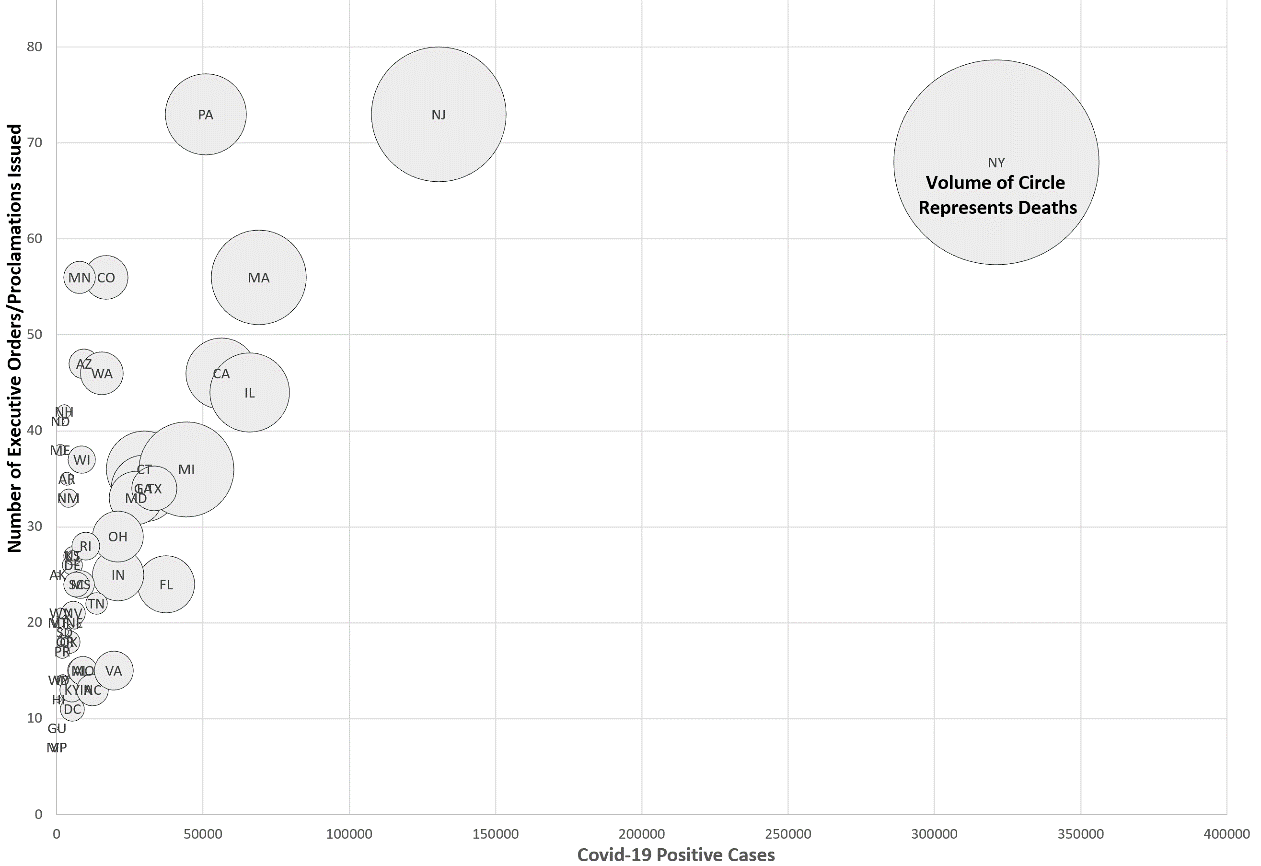

Many legislative and executive mandates commenced during the second week of March. By the end of April, 56 states, commonwealths, territories, and the District of Columbia promulgated a total of 1,618 executive orders and proclamations ranging from 7 to 73 per state. On average the number issued was 29 and the median was 25. As Figure 2 illustrates, the greater the number of cases and deaths, the great the number of executive orders issued. This is not to infer causality but rather to note an apparent correlation.

...the greater the number of cases and deaths, the great the number of executive orders issued.These executive orders dealt with a wide range of issues relating to declaring the state of emergency, mitigation strategies, provision of resources, and suspension of regulations relating to state functions. Specific to the regulation of health profession, 93 emergency declarations and various executive, legislative, and operational actions addressed a range of issues pertinent to access to care, licensure, mobility of practitioners, and other dimensions detailed below (National Council of State Boards of Nursing [NCSBN], 2020a).

Figure 2: Cases, Executive Orders and Deaths by State May 1, 2020

Analysis of Legislative Changes Pertinent to Professional Regulation

The many proclamations and executive orders issued by federal, state, county, and city government during the COVID-19 pandemic have presented boards of nursing with many challenges. In this section, we discuss our analysis of the legislative changes in the context of operational and strategic challenges.

Operational Challenges.

Stay-at-home orders and social distancing requirements placed stress on the day-to-day functioning of regulatory boards. Not all regulatory boards had fully digital offices. As a result, maintaining services through remote working was a challenge. In some cases, as an essential service, staff had to go to the office to maintain licensing, discipline, and other critical functions. Even those boards with fully digital systems, such as those with the Optimal Regulatory Board System (ORBS) platform, had to ensure that their staff had sufficient laptops to securely access the system from home (NCSBN, 2019a).

...maintaining services through remote working was a challenge. Increasingly, communication with boards of nursing has migrated to digital options but there remains physical mail and, in some cases, bills to manually process and pay. The need to reach out to contractors to obtain the necessary information to establish automated clearing house and international wire transfer has accelerated the establishment of fully digital payment systems. Although a small step, this was an overdue change that will remain as an improvement to the efficiency and effectiveness of operational services.

While even prior to the pandemic it was common to connect and run meetings by teleconference, until the crisis most organizations still hosted many face-to-face events. Prior to the pandemic, regulators would hold one-to-one events or small group meetings. However, since the pandemic changes, larger meetings, live events, and interactive, collaborative, problem solving have been conducted almost exclusively via virtual platforms. There are multiple options available to support remote work, and the range of features can vary widely. As individuals interact with colleagues in different organizations, they quickly find that not all systems offer the same features or some may work in unexpected and irritating ways. It is important to capture these observations and use them to shape future software and systems investments.

It is important to capture these observations and use them to shape future software and systems investments.To prevent social isolation of staff and colleagues, most organizations created a series of routine virtual meetings. At the NCSBN this took the form of a single item quick update sessions each morning, bringing together team managers to alert each other to priorities they were working on to solve COVID-19 problems that day. These meetings were initially set for 30 minutes, but after a week it was possible to discuss updates from all key staff in 15 minutes. Additionally, weekly meetings with the entire workforce and key stakeholders were organized to communicate key changes and receive input to direct management toward issues that needed resolution.

Strategic Challenges

Changes brought about through emergency orders and the changing nature of clinical and educational environments spurred a wide range of regulatory issues to address. This included mobility of practitioners; barriers to full scope of practice; and concerns related to nursing education, each discussed below.

Mobility of Practitioners. In New York (NY), Governor Andrew Cuomo issued Executive Order 202.5 authorizing, “…registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, and nurse practitioners licensed and in current good standing in any state in the United States to practice in New York State without civil or criminal penalty related to lack of licensure…” (State of New York, 2020, p. 1). The order suspended the requirement for a nurse to carry a New York issued license to practice nursing in New York (State of New York, 2020). This has, albeit in a small number of cases, resulted in nurses who have a license in another state and who have allegedly contravened the nurse practice act (NPA) undermined public safety. In such cases, the NY board cannot investigate the allegation as the individual nurse does not have a NY license and the home state has no jurisdiction in New York. As a result, patients were and are at risk by nurses who violate another state’s practice act; they would otherwise have been subject to discipline by the jurisdiction where the violation occurred.

The order suspended the requirement for a nurse to carry a New York issued license to practice nursing in New YorkOther orders, in contrast, required registration or temporary licensure or permit processes to authorize practice. Similar effects of these authorizations are already in place in member states of interstate healthcare licensure compacts. Registered nurses (RNs) and licensed practical nurses (LPNs) with multistate licenses are able to practice in all states party to the Nurse Licensure Compact (NLC) without any executive intervention. In those states, neither executive nor legislative action was required to immediately mobilize the RN and LPN workforce. Furthermore, the digital platform that facilitates the privilege to practice in party states affords the public the protections needed by states to investigate and take action should the nurse contravene the nurse practice act.

...the digital platform that facilitates the privilege to practice in party states affords the public the protections needed by states to investigate and take action should the nurse contravene the nurse practice act.New Jersey enacted the NLC, thereby becoming a member in the 2019 legislative session (State of New Jersey, 2019). Though implementation of the law is still underway, the New Jersey Board of Nursing expediated operational processes to allow multistate licensees to practice in New Jersey during the pandemic (New Jersey Division of Consumer Affairs, 2020). Through this operational change, New Jersey was able to safely mobilize a workforce to fill critical provider gaps.

Waivers were also extended to include telehealth and associated services. Emergency proclamations permitted advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) to provide care via telehealth without meeting state requirements for licensing (NCSBN, 2020a). Fourteen states waived restrictions during the pandemic to allow telehealth practice from out of state providers (NCSBN, 2020a). Similar to New York, the state where the patient receives care has no jurisdiction over the telehealth practitioner’s license and the home state where the practitioner is licensed has no power to investigate any infraction that occurs in the jurisdiction where care was delivered. However, for those RNs that have a multi-state license, telehealth services were facilitated by the NLC that already allowed for electronic care and communication across state borders, as well as investigatory processes to enforce the various member states’ nurse practice acts.

Fourteen states waived restrictions during the pandemic to allow telehealth practice from out of state providersRemoving Barriers to Full Scope of Practice. APRNs played a critical role in patient care during the pandemic. In nearly half of the states, APRNs practice to the full extent of their advanced education and training (Federal Trade Commission [FTC], 2014). In the remainder of the states, APRNs are subject to regulatory restrictions unrelated to patient care or safety (FTC, 2014). In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, over twenty state governors used emergency powers to either suspend or reduce these barriers, increasing access to highly skilled APRN care (NCSBN, 2020a). Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards issued Proclamation #38 suspending these restrictions with intent to “assist with increasing Louisiana health care providers’ ability to respond to the current public health emergency,” (State of Louisiana, 2020, pg. 1).

Temporary regulatory waivers and new rules were issued to facilitate care during the pandemic.The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) also worked to reduce barriers. Temporary regulatory waivers and new rules were issued to facilitate care during the pandemic. CMS suspended physician supervision for Medicare/Medicaid billing for certified registered nurse anesthetists (CRNAs) (CMS, 2020). This impacted those states that have removed state restrictions for CRNAs but have not opted out of the CMS provision. With these recently released federal regulation, CRNAs are eligible to practice without supervision. Barriers, however, still exist where state law requires physician supervision (NCSBN, 2020g).

Removing barriers to scope of practice is an important change as there is a wealth of evidence demonstrating the efficiency, effectiveness, safety, quality, and increased access to services of nurses in advance practice roles working to their full scope of practice (Benton et al., 2016; World Health Organization [WHO], 2020a). There is increasing evidence of the wider economic impact that removing barriers to APRNs can have on state economies. As states seek to rebuild economies struck by COVID-19, it will be important to highlight the economic and health advantages of nurses working to their full scope of practice (Conover and Richards, 2015; Myers, et al. 2020; The Perryman Group, 2012; Unruh, et al. 2018).

There is increasing evidence of the wider economic impact that removing barriers to APRNs can have on state economies. APRNs were able to extend their roles and made valuable contributions across institutions in response to the pandemic. To preserve staff and beds for the high number of pandemic patients, facilities cancelled elective procedures and surgeries. Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetists (CRNAs) who ordinarily would be providing anesthesia services for cancelled procedures and surgeries became available to assist during the pandemic. The American Association of Nurse Anesthetists (2020) highlighted the many ways in which CRNAs could support emergency room and critical care services in addition to their normal roles. In particular, CRNAs could be called to support rapid systems assessment, airway management, ventilatory support, vascular volume resuscitation, triage, emergency preparedness, and resource management to support their facilities.

Nursing Education, Entry to Practice and Licensure. When state officials began acknowledging that extraordinary measures were needed to control the viral spread, shelter-in-place orders were issued in 44 states (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020). Hospitals urgently transformed their internal operations, as well as the roles of staff to manage a forecasted tsunami of patients. Many acute care institutions determined they could no longer accommodate student clinical experiences. Nursing students, many of whom were completing their last semester of mandated clinical practice, were removed from hospitals with no recourse.

Many acute care institutions determined they could no longer accommodate student clinical experiences.Nursing education programs and boards of nursing quickly worked to provide alternative clinical experiences for students. These included increasing the use of simulation (NCSBN, 2020b). Currently most states allow programs to substitute up to 50% of clinical experience with simulation (Smiley, 2019). During the pandemic, many BONs approved nursing programs to use more than 50% simulation so that students could fulfill clinical requirements (NCSBN, 2020b). While there is evidence that up to 50% of clinical experience can be substituted with simulation without negatively impacting outcomes (Hayden, et al., 2014), there is no evidence regarding student outcomes beyond 50% simulation. Additionally, if a school has not had a previously established simulation program, enacting simulation to a high degree presents challenges. Schools need adequate facilities and faculty need extensive training (Alexander et al, 2015).

In addition to the lack of availability of clinical sites during the pandemic, many schools closed physical facilities, forcing faculty to teach courses online (Hechinger & Lorin, 2020). If faculty were not adequately trained to teach courses online, students may have experienced a gap in knowledge (Bay View Analytics, 2020). This problem was not unique to the United States and similar issues were identified by Bogossian et al. (2020) in Australia.

Nursing education programs and boards of nursing quickly worked to provide alternative clinical experiences for students. Innovation can also emerge from disruption. To address the sudden changes to nursing education, nursing leaders developed a model for Practice-Academic Partnerships (NCSBN, 2020b). This policy brief, U.S. Nursing Leadership Supports Practice/Academic Partnerships to Assist the Nursing Workforce during the COVID-19 Crisis, recommends that nursing students be employed in healthcare institutions to assist as support workers and be given clinical credit for doing so. Several states, Iowa, Idaho, and Ohio, had already adopted this type of partnership prior to the pandemic (Finkel, 2020; Idaho Board of Nursing, 2020; Ohio Board of Nursing, 2020a). In Michigan, the governor issued an executive order temporarily suspending certain restrictions governing the provision of medical services, which facilitated the development of education practice partnerships (Michigan Office of Governor Gretchen Whitmer, 2020).

Simultaneously, as students struggled to fulfill requirements for their final semester, nine governors issued urgent pleas for schools to release graduating nursing and medical students into the workforce prior to full completion of the last semester and without taking the National Council Licensure Examination (NCLEX), which measures minimal competency for practice (NCSBN, 2019b). While the pandemic exacerbated workforce needs, it is important to remember that across the nation, 15% of all nurse program graduates fail the licensure examination on the first occasion. The licensure examination does not test the entire content of nursing programs but explicitly focuses on those issues that are required for an individual to have minimum competence to practice (NCSBN, 2019b). The work of Yonge et al. (2010) focused on the behavior of students during previous pandemics, and identified that nursing students are willing to volunteer during such events. Although these findings are encouraging, it is critical that policies ensuring both a competent workforce and ensure those supporting public safety remain in place.

...it is critical that policies ensuring both a competent workforce and ensure those supporting public safety remain in place.Ohio House Bill 197 authorized temporary licensure for nursing graduates by suspending the requirement to pass the NCLEX exam. The bill, enacted in late March 2020, provided that these licenses would be valid for ninety days after December 1, 2020; or on the date that is ninety days after the duration of the period of the emergency declared by Executive Order 2020-01D (Ohio Board of Nursing, 2020b). Immediately on receipt of their temporary licenses, a number of these nurses applied for licenses in other states via endorsement. The motivation to gain licenses in other states by endorsement was unknown. However, this would potentially result in a complex network of reciprocated licenses, issued on the false premise that the licensees successfully met minimal competency standards. To prevent this, an addition rule was implemented to the licensure by endorsement algorithm to highlight to the receiving state that the licensee had not yet taken and passed the NCLEX exam. Receiving boards thus had all information needed to inform their decision on granting or not a license via endorsement.

Indiana governor Eric Holcomb issued Executive Order 20-13, which authorized nursing students who have completed all required coursework at an accredited school, and have a certificate of completion, to be issued a temporary license without requiring the NCLEX or a criminal background check. The temporary licensure is limited to 90 days and can be renewed in 30-day increments if the pandemic continues. The order provides that upon the public health emergency ending, “all application procedures for initial licensure will be reinstituted and must be followed” (State of Indiana, 2020, pg. 3). Waiving requirements for licensure, such as criminal background checks, also poses risk. Studies have shown that 18 to 29% of nurses or nurse applicants with a criminal conviction failed to disclose their criminal conviction histories (Blubaugh, 2012; E.H. Zhong et al., 2016). In these cases, during the pandemic, individuals with criminal records that have relevance to the practice of nursing may have gained access to vulnerable patients.

These orders, without question, mobilized nurses into the workforce; however, they also raise concerns. These orders, without question, mobilized nurses into the workforce; however, they also raise concerns. Entering the workforce as a new graduate nurse can be stressful under ordinary circumstances (Boamah, Read, & Laschinger, 2017). In this case, new nurses were entering under the most dire conditions since the pandemic of 1918-1920 (Toner & Waldhorn, 2020). Further, as mentioned above, some may not have completed the final courses and clinical experiences in their nursing programs, yet they were encouraged to enter the workforce during a time when one might speculate whether facilities were able to fully execute orientation and transition to practice programs. According to Spector et al. (2015) and Goode et al. (2018), this may have short- and long-term implications, including impacting retention in the institution.

Crises require competence (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2020). Without the results of the NCLEX examination, what evidence is there to determine whether the new nurse is minimally competent to enter the workforce? Who determines that the nurse has the competence to safely care for patients during a pandemic? With a 15% failure rate for new graduate nurses on the first attempt (NCSBN, 2019c), there is a risk that these nurses could be practicing during the pandemic without the minimum level of competence.

Temporary licensure is not new to nursing regulation. Twenty-four states, under normal circumstances, issue a temporary license/practice permit for licensure by examination candidates. These licenses are valid from thirty days to one year (NCSBN, 2020c). Recipients of these permits should practice under supervision and assigned an experienced mentor. In addition, employers and the BON need to be diligent to ensure that nurses with the temporary license/permit take the NCLEX and report their results to their employer. Employers and BONs need to ensure that nurses who do not pass the NCLEX do not remain in practice on an expired temporary license/permit.

Employers and BONs need to ensure that nurses who do not pass the NCLEX do not remain in practice on an expired temporary license/permit.Issuing temporary licenses/permits, and thus extending the time for new graduates to take the, can have other implications. While it is possible that clinical practice may prepare one for success on the NCLEX, there is evidence that the longer one waits to take the examination, the higher the risk of failure to pass (Woo, Wendt, & Liu, 2009).

While some governors temporarily waived the NCLEX requirement, many did not. New graduate nurses in those states found themselves in a quagmire as test centers closed due to shelter-in-place orders. Closure of the test sites delayed those who were eligible and ready to take the examination and would have postponed their entry into the workforce. However, NCSBN managed to work with test providers and state governments to open, albeit restricted, these centers to healthcare providers with limited testing capacity. The NCLEX, is a high stakes examination requiring multiple layers of security. Re-opening the test sites presented challenges. The test centers not only had to maintain all security requirements, the staff also had to volunteer to work during the pandemic and modifications had to be made to ensure the virus would not spread among testing staff or test candidates.

NCSBN developed a crisis plan to adapt the NCLEX and the test centers for the pandemic. NCSBN developed a crisis plan to adapt the NCLEX and the test centers for the pandemic. In states across the country whose leaders deemed the administration of the examination as an essential service, as many sites as possible were opened. The exam was shortened by removing any content that did not directly contribute to generating the ability estimate of the candidate that is, research items and those questions under development. This reduced the maximum testing time from six to four hours, and allowed seating times twice instead of just once a day (NCSBN, 2020d). NCSBN closely monitored the scores of test candidates and the shortened test time had no impact on candidate outcomes. Test centers met all Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and state level COVID-19 guidelines. Masks, social distancing, and disinfected testing areas are among the adaptions made to provide a safe environment for staff and test candidates (NCSBN, 2020e).

We know from the work of Yonge et al. (2010) that students are often willing to volunteer to work in the clinical setting during pandemics. However, the lack of PPE and the minimal number of clinical hours that some students gained prior to the final months of their programs complicated ability to obtain even voluntary work. Potential employers were looking for experienced practitioners. In Europe, students enter clinical areas early in their programs; almost the entirety of their didactic theoretical content is dedicated to nursing and they gather a minimum of 2300 hours of clinical practice prior to qualification (Keighley, 2009). Hence, over the duration of their program they become known to institutions as clinical staff play a larger role in their education, compared to students in North America. This suggests the need to compare experiences across the Atlantic or elsewhere to identify whether fundamental change in educational program structure is appropriate. For example, evidence from Australia has suggested that the duration of clinical placements has a positive impact on nursing students’ experience of belongingness (Levett-Jones et al. 2008).

Board of Nursing Procedures

BON meetings, deliberations, and disciplinary procedures were adjusted because face-to-face meetings, conferences, and hearings were not possible. The role of the BON is to ensure public protection by allowing only nurses who are competent and safe to practice (Brous, 2012; Raper & Hudspeth, 2008; Russell, 2017). Therefore, other board processes relating to disciplinary procedures had to be implemented. BON meetings, deliberations, and disciplinary procedures were adjusted because face-to-face meetings, conferences, and hearings were not possible. To date, at least 36 regulatory boards are or plan to conduct some or the majority of disciplinary proceedings and meetings virtually. Besides conference calls, other useful platforms include Zoom, Webex, Teams, Google Meet, Uber Conference, Blue Jeans, Hang-out, Skype for Business, AT Conference, A+ Conference, and Conference Nation.

Some nurses with disciplined licenses which were suspended, revoked, or voluntarily surrendered prior to the pandemic requested a reinstatement of their license from the BON so they could work during the pandemic (NCSBN, 2020f). Regardless of intent and necessity, regulatory boards have to make decisions based on the principles of public safety. These disciplinary actions are issued by BONs only when there is strong evidence that a nurse is unsafe or not competent to practice (Brous, 2012; Raper & Hudspeth, 2008). Reasons for these disciplinary actions include, but are not limited to, substance use disorder; misuse of substances; gross negligence and/or substandard care; repeated violations of the standards of care; fraudulent activity; and abuse of a patient. Additional reasons for license suspension or revocation may include nonpayment of student loans; and nonpayment of child support, alimony, or taxes.

To address matters of discipline, BONs and The Tri-Council for Nursing approved the following policy brief: Evaluating Board of Nursing Discipline during the COVID-19 Pandemic (NCSBN, 2020f). Recommendations included BON consideration of a waiver of disciplinary action for licensees who have been removed from practice due to administrative issues that have no nexus to public safety, such as the nonpayment of student loans, child support, alimony or taxes.

Legal and Ethical Challenges

Caring for infectious patients during extreme circumstances such as a pandemic can put a nurse’s health or life at risk and elicit a multitude of ethical and legal questions. Because COVID-19 is highly contagious and there was a shortage of PPE, questions arose pertaining to when a nurse could refuse a patient assignment. Generally, it is believed that a nurse has a social privilege granted through scope of practice, licensure, and title protection and authority to self-regulate through regulatory bodies. In exchange for this privilege they have a duty to offer services (Brous, 2012).

questions arose pertaining to when a nurse could refuse a patient assignment.In addition to the lack of PPE, during early stages of the pandemic safety guidelines regarding droplet precautions were emerging from the WHO, the CDC, and state public health departments (WHO, 2020b; CDC, 2020). These were often not aligned and created misperceptions and anxiety for nurses working on the frontlines.

An example of this misalignment occurred in Oregon. The Oregon Health Authority (OHA) Public Health Division (2020) issued guidance on droplet precautions and PPE that differed from the guidelines issued by WHO and the CDC (WHO, 2020b; CDC, 2020). Nurses working in Oregon institutions that were following the OHA guidance for droplet precautions and PPE, began refusing assignments of COVID-19 patients, inferring that the OHA and the hospital facility were putting them at risk (Oregon Public Health Division, 2020). A review of the OHA website and their published standards indicated they are consistent with droplet precautions (e.g., eye guard, face mask, gown and gloves). These were, in fact, higher standards than the CDC, since the CDC had, at that time, "authorized" use of/reuse of face masks and bandanas (Oregon Public Health Division, 2020).

The BON went on to recognize that all nurses and nursing assistants are entitled to keep themselves safe through appropriate use of PPE. In response, the Oregon BON issued a position statement (Oregon State BON, 2020) to provide clarification; nurses could not refuse an assignment solely because the employer was utilizing OHA guidelines rather than WHO or CDC guidelines. The BON went on to recognize that all nurses and nursing assistants are entitled to keep themselves safe through appropriate use of PPE. Furthermore, the BON highlighted that the NPA will always support the ability of a nurse to refuse an assignment when they do not have the knowledge, skills, competencies, and abilities to safely accept it. Having PPE, or not having PPE, comes under the “abilities” section of the practice act.

How the word “abnormal” will be legally interpreted during this pandemic is unknown. Refusal of a patient assignment has legal implications. Most “refusal to work” protections only provide legal protection when the nurse is confronting an abnormally dangerous situation that is not a foreseeable condition or something that is not an inherent part of their position. How the word “abnormal” will be legally interpreted during this pandemic is unknown. “Refusal to work” protections may be less pertinent since the entire world risks exposure to COVID-19. Generally, an infectious disease is classified as an expected condition for which a nurse would provide care (Coleman, 2008).

Generally, an infectious disease is classified as an expected condition for which a nurse would provide careThese ethical dilemmas are not unique to the COVID-19 pandemic and have been the subject of scholarly work on several occasions (Malm et al., 2008; Mareiniss, 2008). Issues of duty to care and the use of emergency standards of care where normal practice is set aside due to overwhelming numbers of patients or lack of physical resources (e.g., ventilators and other equipment) raise questions as to the adequacy of existing codes of ethics and educational preparation (Leider et al., 2017). Accordingly, ethical considerations is a topic that requires careful scrutiny if lessons are to be learned.

Limitations

There are far more lessons to learn from this experience.Data were collected during a six-week window of the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, our work was an initial analysis of events that are likely to continue to unfold. The analysis focused exclusively on the regulatory aspects of the crisis. There are far more lessons to learn from this experience. It is advisable to conduct additional study of both the immediate and long-term regulatory effects in dealing with the pandemic, to include practice, education and research impacts.

Conclusions

Myriad challenges have confronted healthcare providers, educators, legislators, and regulators among many others during the COVID-19 pandemic, primarily because of the lack of preparation. If there is one fundamental lesson to be learned it is to be prepared and have systems and resources in place to meet an impending crisis of any kind. Many of the lessons learned will provide a solid foundation for overall improvements in policies and processes beyond the pandemic, and may remain in place upon establishment of the new normal.

If there is one fundamental lesson to be learned it is to be prepared and have systems and resources in place...Some of the regulatory waivers, both state and federal, were issued as emergency declarations but are grounded in evidence. For example, APRNs are competent and safe to practice to the full extent of their education and license without any type of mandated supervision. Making these waivers permanent regulations where still needed will ensure that access to care continues far beyond the current COVID-19 crisis.

Other waivers, however, posed a risk to the public health, welfare and safety. New graduates entering practice must be required to take the NCLEX examination. There is currently no other way to provide the employer or the public with assurance that a nurse is minimally competent for practice. Likewise, allowing nurses to practice across state borders without the vetting that occurs through obtaining a multistate license under the NLC also poses a risk. Multistate license holders have met 11 uniform requirements to ensure that they have an active, unencumbered license (e.g., clear criminal background check). Nurses need to be able to practice across state borders, both physically and electronically, via telehealth. The NLC supports this outcome with the assurance that the nurse is competent and safe to practice. In the time of an emergency, this is especially relevant. Hence, progress is needed for the United States into become a compact nation; individual states would issue a multi-state license and nurses hold the privilege to practice in all other party states and territories.

Nurses need to be able to practice across state borders, both physically and electronically, via telehealth. The pandemic is providing a plethora of opportunities for nurse educators. All nurse educators should receive instruction in online teaching and learning so faculty can continue programs seamlessly and effectively in the event of a recurrence. There is also an opportunity to form practice/academic partnerships. Those who work in practice must be invested in students. Student employment in hospitals and long-term care facilities that offer simultaneous clinical credit in a nursing course is a win-win for employers and nursing programs; in the end this partnership will result in new graduates who are better prepared to meet the challenges of the future.

Those who work in practice must be invested in students. This pandemic also challenges us to do more research. Aside from the waivers with evidence to support converting them into permanent regulations, further examination of outcomes is needed. We suggest the following questions as a start:

- What were the effects of issuing temporary licenses without NCLEX results?

- What are the outcomes of substituting simulation for greater than 50% of the clinical experience?

- Will students benefit equally from virtual simulation as they do high fidelity?

- What were/are the effects of the pandemic on the workforce?

- Will a higher number of nurses experience the effects of burnout?

- Will we see an increase in substance use among healthcare professionals?

- How will the pandemic affect the retention of new graduates?

These are all questions to be explored and will, in due course, offer new data and insights about the effects of COVID-19 on nurses and the nursing profession.

Regulators have significant responsibilities to consider. First, they must assess their technology and whether they are able to sustain operations from a remote location when necessary. Regulators who can work with legislators should continue to encourage:

- adoption of the NLC in states where this is not in place, and

- waivers pertaining to full practice authority for APRNs as permanent regulations to increase access to care both in-person and via telehealth and as a potential means to help the economy recover.

In sum, telehealth will no doubt become a more frequent and useful tool to promote healthcare. Current systems would benefit from further evaluation as additional regulations may be needed. Regulators can also promote practice/academic partnerships and call for a transformation in the way we teach nursing students, both in ordinary times as well as emergencies.

From ethical and legal challenges to those of technology, there are many stories to share and lessons to be learned.Finally, nurse leaders need to learn from one another. From ethical and legal challenges to those of technology, there are many stories to share and lessons to be learned. Winston Churchill, in February 1945 during talks with Stalin and Roosevelt, is often credited with the statement that [we] should never let a good crisis go to waste, thus action is needed now. Only by communicating and sharing our experiences will we all be better prepared for future pandemics and emergencies.

Authors

David C. Benton, PhD, RN, FRCN, FAAN

Email: dbenton@ncsbn.org

Dr. Benton hails from the North East of Scotland. He completed his RN education at Highland College of Nursing and Midwifery in Inverness, specializing in both general and mental health practice. He undertook his MPhil degree studying the application of computer assisted learning to post basic psychiatric nurse education at the University of Abertay and received a PhD Summa Cum Laude from the University of Complutence Spain, for his groundbreaking work on an international comparison of nursing legislation. Prior to his current post as Chief Executive Officer of the National Council of State Boards of Nursing, he worked for ten years at the International Council of Nurses based in Geneva, Switzerland. Benton is a prolific author and has published over 200 papers on leadership, workforce, health policy, social network analysis, bibliometrics, and regulation. He is a global expert in regulation and health and nursing policy and has advised governments around the world about both nursing legislation and wider health policy issues.

Maryann Alexander, PhD, RN, FAAN

Email: malexander@ncsbn.org

Maryann Alexander is Chief Officer, Nursing Regulation for the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) and is Editor in Chief of the Journal of Nursing Regulation. Prior to her role at NCSBN, Dr. Alexander was the executive officer of the Illinois Board of Nursing. She was also an Advanced Practice Registered Nurse and an Assistant Professor at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago. She received her Bachelor of Science in Nursing and Master of Science degrees from Northwestern University. Her PhD is in Nursing with an emphasis in Health Policy from the University of Illinois at Chicago. Her policy experience includes an internship in the Office of Science Policy at the National Institutes of Health. She is a fellow in the American Academy of Nursing, has authored articles and book chapters; won several national research awards; and has given numerous presentations nationally and internationally.

Rebecca Fotsch, JD

Email: rfotsch@ncsbn.org

Rebecca Fotsch is an attorney and currently serves as the Director of State Advocacy and Legislative Affairs at the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN). She received her BA in political science from Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin and her law degree from Loyola University Chicago School of Law. After law school, Rebecca served as an Assistant Counsel to the Speaker of the House in Illinois as well as a Legislative Liaison for the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency. In addition to her legislative work at NCSBN, Rebecca is also an author of Policy Perspectives in the Journal of Nursing Regulation as well as faculty for the International Center for Regulatory Scholarship.

Nicole Livanos, JD, MPP

Email: nlivanos@ncsbn.org

Before arriving at NCSBN, Nicole Livanos received a J.D. and Master in Public Policy from Loyola University Chicago School of Law. While in law school, Nicole clerked for the Uniform Law Commission, Illinois Office of the Attorney General, and Lawyers’ Committee for Better Housing. Nicole served as the Executive Editor of Loyola’s Public Interest Law Reporter from 2014-2015. Prior to law school, Nicole was a Research and Appropriations Staffer for the Illinois Speaker of the House where she focused on state revenue policy and legislation. Nicole is also a published author in the Journal of Nursing Regulation and faculty for the International Center for Regulatory Scholarship. Nicole leads advocacy efforts for NCSBN’s Nursing America campaign aimed at advancing APRN legislation across the states.

References

Alexander, M., Durham, C. F., Hooper, J. I., Jeffries, P. R., Goldman, N., Kardong-Edgre, S. Kesten, K. S., Spector, N. Tagliareni, E., Radtke, B., & Tillman, C. (2015). NCSBN simulation guidelines for prelicensure nursing programs. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 6(3), 39-42. doi: 10.1016/S2155-8256(15)30783-3

American Association of Nurse Anesthetists [AANA]. (2020, March 21). Utilizing CRNAs unique skill set during the COVID-19 crisis. ANA.Retrieved from https://www.aana.com/home/aana-updates/2020/03/21/utilizing-crnas-unique-skill-set-during-covid-19-crisis

American Nurses Association [ANA]. (2020). Crisis standard of care: COVID-19 pandemic. Retrieved from https://www.nursingworld.org/~496044/globalassets/practiceandpolicy/work-environment/health--safety/coronavirus/crisis-standards-of-care.pdf

Bay View Analytics. (2020). Digital learning pulse survey: Immediate priorities. A snapshot of higher education’s response to the COVID-19 epidemic. Retrieved from https://embed.widencdn.net/pdf/plus/cengage/1yhakzkaya/higher-educations-response-to-covid19-infographic-1369680.pdf/?utm_campaign=in_movetoonline_dg_fy2021&&utm_content=1373605

Benton, D.C., Cusack, L., Jabbour, R., & Penney, C. (2016). A bibliographic exploration of nursing’s scope of practice. International Nursing Review, 64(2) 224-232. doi: 10.1111/inr.12337

Blubaugh, M. (2012). Using electronic fingerprinting for criminal background checks. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 2(4), 50-52. doi: 10.1016/S2155-8256(15)30242-8

Boamah, S.A., Read, E.A., & Laschinger, H.K.S. (2017). Factors influencing new graduate nurse burnout development, job satisfaction and patient care quality: A time-lagged study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 73(5), 1182-1195. doi: 10.1111/jan.13215

Bogossian, F., McKenna, L., & Levett-Jones, T. (2020). Mobilising the nursing student workforce in COVID-19: The value proposition. Collegian. 27(2), 147-149. doi: 10.1016/j.colegn.2020.04.004

Bowen, G.A. (2009). Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal. 9(2) 27-44. doi: 10.3316/QRJ0902027

Brous, E. (2012). Nursing licensure and regulation. In D. J. Mason, J. K. Leavitt, & M. W. Chaffee (Eds.). Policy & politics in nursing and health care (6th ed.). Elsevier Saunders.

Chan, J.L. & Burkle, F.M. (2013) A framework and methodology for navigating disaster and global health crisis literature. PLoS Current Disasters, 5(1). doi: 10.1371/currents.dis.9af6948e381dafdd3e877c441527cba0

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. (2020, July 16). Optimizing Supply of PPE and other Equipment during Shortages. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/ppe-strategy/index.html

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS]. (2020, March 30). Trump administration makes sweeping regulatory changes to help U.S. healthcare system address COVID-19 patient surge. Retrieved from https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/trump-administration-makes-sweeping-regulatory-changes-help-us-healthcare-system-address-covid-19

Coleman, C.H. (2008). Beyond the call of duty: Compelling health care professionals to work during an influenza pandemic. Iowa Law Review, Forthcoming, Seton Hall Public Law Research Paper No. 1121421. Retrieved from : https://ssrn.com/abstract=1121421

Conover, C. & Richards, R. (2015) Economic benefits of less restrictive regulation of advanced practice nurses in North Carolina. Nursing Outlook, 63(5), 585-592. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2015.05.009

Davis, J.B. (2020) Pandemic power plays: Civil liberties in the time of COVID-19. American Bar Association. Retrieved from: https://www.abajournal.com/web/article/pandemic-power-plays-civil-liberties-in-the-time-of-covid-19

Federal Trade Commission [FTC]. (2014). Policy perspectives: Competition and the regulation of Advanced Practice Nurses. Retrieved from: https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/reports/policy-perspectives-competition-regulation-advanced-practice-nurses/140307aprnpolicypaper.pdf

Finkel, E. (2020, April 19). Urgently needed, but facing hurdles to complete. American Association of Community Colleges. Retrieved from http://www.ccdaily.com/2020/04/urgently-needed-but-facing-hurdles-to-complete/

Goode, C. J., Glassman, K. S., Ponte, P. R., Krugman, M., & Peterman, T. (2018). Requiring a nurse residency for newly licensed registered nurses. Nursing Outlook, 66(3), 329-332. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2018.04.004

Gostin, L.O. (2004). Pandemic influenza: Public health preparedness for the next global health emergency. The Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics, 32(4), 565-573. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2004.tb01962.x

Hayden, J. K., Smiley, R. A., Alexander, M., Kardong-Edgren, S., & Jeffries, P. R. (2014). The NCSBN national simulation study: A longitudinal, randomized, controlled study re-placing clinical hours with simulation in prelicensure nursing education. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 2(5), S1–S40. doi: 10.1016/S2155-8256(15)30062-4

Hechinger, J. & Lorin, J. (2020, March 19). Coronavirus forces $600 billion higher education industry online. Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-19/colleges-are-going-online-because-of-the-coronavirus

Idaho Board of Nursing. (2020). Nurse apprentice program. State of Idaho Board of Nursing. Retrieved from https://ibn.idaho.gov/education/nursing-apprentice-program/

Kaiser Family Foundation. (2020, June 4). State data and policy actions to address Coronavirus. KFF. Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/state-data-and-policy-actions-to-address-coronavirus/

Keighley, T. (2009). European Union Standards for Nursing and Midwifery: Information for Accession Countries, (2nd Ed.). World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. Retrieved from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/102200/E92852.pdf

Leider, J.P., DeBruin, D., Reynolds, N., Koch, A., & Seaberg, J. (2017). Ethical guidance for disaster response, specifically around crisis standards of care: A systematic review. Public Health Ethics, 107(9), e1-e9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303882

Levett-Jones, T., Lathlean, J., Higgins, I., & McMillan, M. (2008). The duration of clinical placements: A key influence on nursing students’ experience of belongingness. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 26(2), 8-16. http://www.ajan.com.au/ajan_26.2.html

Madhav, N., Oppenheim, B., Gallivan, M., Mulembakani, P., Rubin, E., & Wolf, N. (2018). 17 – Pandemics: Risks, impacts, and mitigation. In Disease Control Priorities: Improving Health and Reducing Poverty, (3rd Ed.). Jamison, D.T., Gelband, H., Horton, S.E., Jha, P.K., Laxminarayan, R., Mock, C.N., & Nugent, R. The World Bank Group. Retrieved from: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/527531512569346552/pdf/121615-PUB-HOLD-embargo-date-is-12-6-2017-ADD-BOX-405304B.pdf

Malm, H., May, T., Francis, L.P., Omer, S.B., Salmon, D.A., & Hood, R. (2008) Ethics, pandemics, and the duty to treat. The American Journal of Bioethics, 8(8), 4-19. doi: 10.1080/15265160802317974

Mareiniss, D.P. (2008). Healthcare professionals and the reciprocal duty to treat during a pandemic disaster. American Journal of Bioethics, 8(8), 39-41. doi: 10/1080/15265160802318147

Michigan Office of Governor Gretchen Whitmer. (2020). Executive Order 2020-30 (COVID-19): Temporary relief from certain restrictions and requirements governing the provision of medical services. State of Michigan. Retrieved from: https://www.michigan.gov/whitmer/0,9309,7-387-90499_90705-523481--,00.html

Myers, C.R., Chang, C., Mirvis, D., & Stansberry, T. (2020). The macroeconomic benefits of Tennessee APRNs having full practice authority. Nursing Outlook, 68(2) 155-161. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2019.09.003

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2019a). Rising to the challenge the optimal regulatory board system (ORBS). In Focus. Summer 2019, 16-21 https://www.ncsbn.org/InFocus_Summer_2019.pdf

National Council of State Boards of Nursing .(2019b). NCLEX-RN® Examination: Test plan for the National Council Licensure Examination for Registered Nurses. National Council of State Boards of Nursing. Retrieved from: https://www.ncsbn.org/2019_RN_TestPlan-English.pdf

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2019c). 2019 Number of candidates taking NCLEX examination and percent passing, by candidate type. National Council of State Boards of Nursing. Retrieved from: https://www.ncsbn.org/Table_of_Pass_Rates_2019_Q4.pdf

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2020a). State Response to COVID-19 (APRNs). National Council of State Boards of Nursing. Retrieved from: https://www.ncsbn.org/APRNState_COVID-19_Response_4_30.pdf

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2020b). Policy brief: U.S. nursing leadership supports practice/academic partnerships to assist the nursing workforce during the COVID-19 crisis. National Council of State Boards of Nursing. Retrieved from: https://www.ncsbn.org/Policy_Brief_US_Nursing_Leadership_COVID19.pdf

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2020c). Member board profiles. National Council of State Boards of Nursing. Retrieved from https://www.ncsbn.org/profiles.htm

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2020d). Summary of modifications to the NCLEX-RN and NCLEX-PN examinations. National Council of State Boards of Nursing. Retrieved from https://www.ncsbn.org/Modified_NCLEX_Exams_Information.pdf

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2020e). COVID-19 impact on NCLEX candidates. National Council of State Boards of Nursing. Retrieved from https://www.ncsbn.org/14428.htm

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2020f). Evaluating board of nursing discipline during the COVID-19 pandemic. National Council of State Boards of Nursing. Retrieved from https://www.ncsbn.org/Policy-Brief-US-Nursing-Discipline_COVID19.pdf

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2020g). APRN Consensus Model by state. National Council of State Boards of Nursing. Retrieved from https://www.ncsbn.org/APRN_Consensus_Grid_Apr2019.pdf

New Jersey Division of Consumer Affairs. (2020). Executive order No. 103 (Murphy). State Government of New Jersey. Retrieved from: https://www.njconsumeraffairs.gov/COVID19/Documents/Accelerated-Temp-Board-Waivers-Combined.pdf

Ohio Board of Nursing. (2020a). Practice/academic partnerships to assist the nursing workforce during the COVID-19 declared emergency. Ohio Board of Nursing. Retrieved from https://nursing.ohio.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Practice-Academic-Partnerships.pdf

Ohio Board of Nursing. (2020b). Coronavirus omnibus legislation (HB197) – RN and LPN initial licensing FAQs. Ohio Board of Nursing. Retrieved from https://nursing.ohio.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/FAQs-COVID-19-Licensure.pdf

Oregon Public Health Division. (2020). Provisional guidance: Clinical care and healthcare infection prevention and control for COVID-19. Oregon Health Authority. Retrieved from: https://sharedsystems.dhsoha.state.or.us/DHSForms/Served/le2288J.pdf

Oregon State Board of Nursing. (2020). Position statement: COVID-19. Oregon State Board of Nursing. Retrieved from: https://www.oregon.gov/osbn/Documents/OSBN_COVID_PracticeStatement.pdf

The Perryman Group. (2012). The economic benefits of more fully utilizing advanced practice registered nurses in the provision of health care in Texas: An analysis of local and statewide effects on business activity. The Perryman Group. https://s3.amazonaws.com/enp-network-assets/production/attachments/35661/original/Texas-Perryman_APRN_Ultilization_Economic_Impact_Report_May_2012.pdf?2014

Raper, J.L. & Hudspeth, R. (2008). Why boards of nursing disciplinary actions do not always yield the expected results. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 32(4), 338-345. doi: 10.1097/01.NAQ.0000336733.10620.32

Russell, K. (2017). Nurse practice acts guide and govern: Update 2017. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 8(3), 18- 25. doi: 10.1016/S2155-8256(17)30156-4

Smiley, R. (2019.) Survey of simulation use in prelicensure nursing programs: Changes and advancements, 2010-2017. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 9(4), 48-61. doi: 10.1016/S2155-8256(19)30016-X

Spector, N., Blegen, M. A., Silvestre, J., Barnsteiner, J., Lynn, M. R., Ulrich, B., Fogg, L., & Alexander, M. (2015). Transition to practice study in hospital settings. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 5(4), 24-38. doi: 10.1016/S2155-8256(15)30031-4

State of Indiana. (2020). Directives to manage Indiana’s health care response for Hoosiers with COVID-19 during the public health emergency (Executive Order 20-13). State of Indiana. Retrieved from https://www.in.gov/gov/files/Executive%20Order%2020-13%20Medical%20Surge.pdf

State of Louisiana. (2020). Proclamation 38 JBE 2020: Additional measures for COVID-19 funeral services and internments, emergency temporary suspension of certain licensure, scope of practice, certification requirements for healthcare providers. State of Louisiana. https://gov.louisiana.gov/assets/Proclamations/2020/38-JBE-2020.pdf.

State of New Jersey. (2019). Senate bill No. 594. 219th Legislature, State Government of New Jersey. https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/2020/Bills/S1000/594_I1.HTM

State of New York. (2020). Emergency Order 202_5 continuing temporary suspension and modification of laws relating to the disaster and emergency. State of New York. Retrieved from: https://www.governor.ny.gov/sites/governor.ny.gov/files/atoms/files/EO_202_35.pdf

Toner, E. & Waldhorn, R. (2020). What US hospitals should do now to prepare for a COVID-19 pandemic. Clinicians’ Biosecurity New, Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security. Retrieved from: https://www.centerforhealthsecurity.org/cbn/2020/cbnreport-02272020.html

Trickey, F.D. (1965). Constitutional and statutory bases of governors' emergency powers. Michigan Law Review, 64(2), 290-307. Retrieved from: https://repository.law.umich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5466&context=mlr

Unruh, L., Rutherford, A., Schirle, L., & Brunell, M.L. (2018). Benefits of less restrictive regulation of advanced practice registered nurses in Florida. Nursing Outlook, 66(6), 539-550. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2018.09.002

Woo, A., Wendt, A., & Liu, W. (2009). NCLEX Pass Rates: An investigation into the effect of lag time and retake attempts. Journal of Nursing Administration’s Healthcare Law, Ethics and Regulation, 11(1), 23-26. doi: 10.1097/NHL.0b013e31819a78ce

World Health Organization. (2020a). State of the world‘s nursing 2020: Investing in education, jobs and leadership. World Health Organization. Retrieved from: https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1274201/retrieve

World Health Organization. (2020b, August 3). WHO COVID-19 preparedness and response report 1 February to 30 June 2020. Geneva, World Health Organization. Geneva, World health organization. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/who-covid-19-preparedness-and-response-progress-report---1-february-to-30-june-2020

Yonge, O., Rosychuk, R.J., Bailey, T.M., Lake, R., & Marrie, T.J. (2010). Willingness of university nursing students to volunteer during a pandemic. Public Health Nursing, 27(2), 174-180. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2010.00839.x

Zhong, E.H., McCarthy, C., & Alexander, M. (2016) A review of criminal convictions among nurses 2012-2013. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 7(1), 27-33. doi: 10.1016/S2155-8256(16)31038-9