The impact of evidence-based practice (EBP) has echoed across nursing practice, education, and science. The call for evidence-based quality improvement and healthcare transformation underscores the need for redesigning care that is effective, safe, and efficient. In line with multiple direction-setting recommendations from national experts, nurses have responded to launch initiatives that maximize the valuable contributions that nurses have made, can make, and will make, to fully deliver on the promise of EBP. Such initiatives include practice adoption; education and curricular realignment; model and theory development; scientific engagement in the new fields of research; and development of a national research network to study improvement. This article briefly describes the EBP movement and considers some of the impact of EBP on nursing practice, models and frameworks, education, and research. The article concludes with discussion of the next big ideas in EBP, based on two federal initiatives, and considers opportunities and challenges as EBP continues to support other exciting new thinking in healthcare.

Key words: EBP, quality improvement, education, research network, translational science, Institute of Medicine

Over the past decade, nurses have been part of a movement that reflects perhaps more change than any two decades combined. The recommendation that nurses lead interprofessional teams in improving delivery systems and care brings to the fore the necessity for new competencies, beyond evidence-based practice, that are requisite as nurses transform healthcare. Directions in nursing education in the 1960s established nursing as an applied science. This was the entry of our profession into the age of knowledge. Only in the mid-1990s did it become clear that producing new knowledge was not enough. To affect better patient outcomes, new knowledge must be transformed into clinically useful forms, effectively implemented across the entire care team within a systems context, and measured in terms of meaningful impact on performance and health outcomes. The recently-articulated vision for the future of nursing in the Future of Nursing report (IOM, 2011a) focuses on the convergence of knowledge, quality, and new functions in nursing. The recommendation that nurses lead interprofessional teams in improving delivery systems and care brings to the fore the necessity for new competencies, beyond evidence-based practice (EBP), that are requisite as nurses transform healthcare. These competencies focus on utilizing knowledge in clinical decision making and producing research evidence on interventions that promote uptake and use by individual providers and groups of providers.

This discussion highlights some of the responses and initiatives that those in the profession of nursing have taken to maximize the valuable contributions that nurses have made, can make, and will make, to deliver on the promise of EBP. A number of selected influences of evidence-based practice trends on nursing and nursing care quality are explored as well as thoughts about the “next big ideas” for moving nursing and healthcare forward.

The EBP Movement

EBP is aimed at hardwiring current knowledge into common care decisions to improve care processes and patient outcomes.Evidence-based practice holds great promise for...producing the intended health outcome. Following the alarming report that major deficits in healthcare caused significant preventable harm (IOM, 2000) a blueprint for healthcare redesign was advanced in the first Quality Chasm report (IOM, 2001). A key recommendation from the nation’s experts was to employ evidence-based practice. The chasm between what we know to be effective healthcare and what was practiced was to be crossed by using evidence to inform best practices.

Evidence-based practice holds great promise for moving care to a high level of likelihood for producing the intended health outcome. The definition of healthcare quality (Box 1) is foundational to evidence-based practice.

Box 1. Definition of Quality Healthcare

| Definition of Quality Healthcare Degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge (IOM 1990; 2013, para 3). |

The phrases in this definition bring into focus three aspects of quality: services (interventions), targeted health outcomes, and consistency with current knowledge (research evidence). It expresses an underlying belief that research produces the most reliable knowledge about the likelihood that a given strategy will change a patient's current health status into desired outcomes. Alignment of services with current professional knowledge (evidence) is a key goal in quality. The definition also calls into play the aim of reducing illogical variation in care by standardizing all care to scientific best evidence.

The EBP movement began with the characterization of the problem—the unacceptable gap between what we know and what we do in the care of patients (IOM, 2001). In the report, Crossing the Quality Chasm (IOM, 2001), IOM experts issued the statement that still drives today’s quality improvement initiatives: “Between the health care we have and the care we could have lies not just a gap but a chasm” (IOM, 2001, p. 1) and urged all health professions to join efforts for healthcare transformation.

Development of evidence-based practice is fueled by the increasing public and professional demand for accountability in safety and quality improvement in health care. A major part of the proposed solution to cross this chasm was “evidence-based practice.” Experts continue to generate direction-setting IOM Chasm reports (IOM, 2003; IOM, 2008a; IOM, 2008b; IOM, 2011a); each report consistently identifies evidence-based practice (EBP) as crucial in closing the quality chasm. The intended effect of EBP is to standardize healthcare practices to science and best evidence and to reduce illogical variation in care, which is known to produce unpredictable health outcomes. Development of evidence-based practice is fueled by the increasing public and professional demand for accountability in safety and quality improvement in health care.

Leaders in the field have defined EBP as “Integration of best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values” (Sackett et al, 2000, p. ii). Therefore, EBP unifies research evidence with clinical expertise and encourages individualization of care through inclusion of patient preferences. While this early definition of EBP has been paraphrased and sometimes distorted, the original version remains most useful and is easily applied in nursing, successfully aligning nursing with the broader field of EBP. The elements in the definition emphasize knowledge produced through rigorous and systematic inquiry; the experience of the clinician; and the values of the patient, providing an enduring and encompassing definition of EBP.

The entry of EBP onto the healthcare improvement scene constituted a major paradigm shift. The EBP process has been highly applied, going beyond any applied research efforts previously made in healthcare and nursing. This characteristic of EBP brought with it other shifts in the research-to-practice effort, including new evidence forms (systematic reviews), new roles (knowledge brokers and transformers), new teams (interprofessional, frontline, mid- and upper-management), new practice cultures (just culture, healthcare learning organizations), and new fields of science to build the “evidence on evidence-based practice” (Shojania & Grimshaw, 2005). The entry of EBP onto the healthcare improvement scene constituted a major paradigm shift. This shift was apparent in the way nurses began to think about research results, the way nurses framed the context for improvement, and the way nurses employed change to transform healthcare.

Impact on Nursing Practice

In this wide-ranging effort, another significant player was added…the policymaker. For EBP to be successfully adopted and sustained, nurses and other healthcare professionals recognized that it must be adopted by individual care providers, microsystem and system leaders, as well as policy makers. Federal, state, local, and other regulatory and recognition actions are necessary for EBP adoption. For example, through the Magnet Recognition Program® the profession of nursing has been a leader in catalyzing adoption of EBP and using it as a marker of excellence.

A recent survey of the state of EBP in nurses indicated that, while nurses had positive attitudes toward EBP and wished to gain more knowledge and skills, they still faced significant barriers in employing it in practice. In spite of many significant advances, nurses still have more to do to achieve EBP across the board. A recent survey of the state of EBP in nurses indicated that, while nurses had positive attitudes toward EBP and wished to gain more knowledge and skills, they still faced significant barriers in employing it in practice (Melnyk, Fineout-Overholt, Gallagher-Ford, & Kaplan, 2012). One example of implementation of EBP points to the challenges of change. The evidence-based program, Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety (TeamSTEPPS®) (AHRQ, 2008) carries with it proven effectiveness of reducing patient safety issues and the program is available with highly-developed training and learning materials. Yet, because of the change necessary to fully implement and sustain the program across the system supported by organizational culture, a sophisticated implementation plan is required before the evidence-based intervention is adopted across an institution. While agency policy may be set, implementation and sustainment of TeamSTEPPS® remain challenging.

Impact on Nursing Models and Frameworks

Early in the EBP movement, nurse scientists developed models to organize our thinking about EBP. A number of EBP models were developed by nurses to understand various aspects of EBP. Forty-seven prominent EBP models can be identified in the literature. These frameworks guide the design and implementation of approaches intended to strengthen evidence-based decision making. Forty-seven prominent EBP models can be identified in the literature. Once analyzed, these models can be grouped into four thematic areas: (1) EBP, Research Utilization, and Knowledge Transformation Processes; (2) Strategic/ Organizational Change Theory to Promote Uptake and Adoption of New Knowledge; and (3) Knowledge Exchange and Synthesis for Application and Inquiry (Mitchell, Fisher, Hastings, Silverman, & Wallen, 2010). Listed among models in Category 1 is the ACE Star Model of Knowledge Transformation (Stevens, 2004); this model is the exemplar for the present discussion of the impact of EBP on nursing models and frameworks.

The ACE Star Model of Knowledge Transformation (Stevens, 2004) was developed to offer a simple yet comprehensive approach to translate evidence into practice. As explained in the ACE Star Model, one approach to understanding the use of EBP in nursing is to consider the nature of knowledge and knowledge transformation necessary for utility and relevance in clinical decision making. Rather than having clinicians submersed in the volume of research reports, a more efficient approach is for the clinician to access a summary of all that is known on the topic. Likewise, rather than requiring frontline providers to master the technical expertise needed in scientific critique, their point-of-care decisions would be better supported by evidence-based recommendations in the form of clinical practice guidelines.

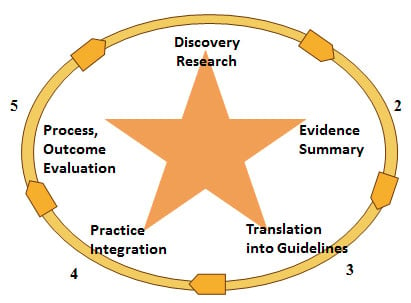

The ACE Star Model of Knowledge Transformation highlights barriers encountered when moving evidence into practice and designates solutions grounded in EBP. The model explains how various stages of knowledge transformation reduce the volume of scientific literature and provide forms of knowledge that can be directly incorporated in care and decision making. The ACE Star Model emphasizes crucial steps to convert one form of knowledge to the next and incorporate best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient preferences thereby achieving EBP. Depicted in Figure 1, the model is a five-point star, defining the following forms of knowledge: Point 1 Discovery, representing primary research studies; Point 2 Evidence Summary, which is the synthesis of all available knowledge compiled into a single harmonious statement, such as a systematic review; Point 3 Translation into action, often referred to as evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, combining the evidential base and expertise to extend recommendations; Point 4 Integration into practice is evidence-in-action, in which practice is aligned to reflect best evidence; and Point 5 Evaluation, which is an inclusive view of the impact that the evidence-based practice has on patient health outcomes; satisfaction; efficacy and efficiency of care; and health policy.

Figure 1. ACE Star Model of Knowledge Transformation

|

Copyright Stevens 2004. Reproduced with permission.

Quality improvement of healthcare processes and outcomes is the goal of knowledge transformation. Important new knowledge resources have been developed and advanced owing to the EBP movement. The importance of Point 2 and Point 3 forms of knowledge has been underscored by several recent reports on the role of systematic reviews (IOM, 2008a; IOM, 2008b; IOM, 2011b) and clinical practice guidelines (IOM, 2008a; IOM, 2008b , IOM, 2011c) in "knowing what works in healthcare." As an important new form of knowledge, systematic reviews are characterized as the central link between research and clinical decision making (IOM, 2008). Likewise, the function of clinical practice guidelines is to guide practice (IOM, 2008). Important new knowledge resources have been developed and advanced owing to the EBP movement. While resources were available for Point 1, only recently have resources been developed for the knowledge forms on Point 2, 3, 4, and 5 of the Model. These resources are outlined in Table 1.

| Table 1. Resources for Forms of Knowledge in the Star Model. | |

| Form of Knowledge | Description of Resources |

| Point 1-Discovery | Bibliographic Databases such as CINAHL-provide single research reports, in most cases, multiple reports. |

| Point 2-Evidence Summary | Cochrane Collaboration Database of Systematic Reviews-provides reports of rigorous systematic reviews on clinical topics. See www.cochrane.org/ |

| Point 3-Translation into Guidelines | National Guidelines Clearinghouse-sponsored by AHRQ, provides online access to evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. See www.guideline.gov |

| Point 4-Integration into Practice | AHRQ Health Care Innovations Exchange-sponsored by AHRQ, provides profiles of innovations, and tools for improving care processes, including adoption guidelines and information to contact the innovator. See http://innovations.ahrq.gov/ |

| Point 5-Evaluation of Process and Outcome | National Quality Measures Clearinghouse-sponsored by AHRQ, provides detailed information on quality measures and measure sets. See http://qualitymeasures.ahrq.gov/ |

Impact on Nursing Education

Following the influential Crossing the Quality Chasm report (IOM, 2001), experts emphasized that the preparation of health professionals was crucial to bridging the chasm (IOM, 2003). The Health Professions Education report (IOM, 2003) declared that current educational programs do not adequately prepare nurses, physicians, pharmacists or other health professionals to provide the highest quality and safest health care possible. The conclusion was that education for all health professions were in need of “a major overhaul” to prepare health professions with new skills to assume new roles (IOM, 2003). This overhaul would require changing way that health professionals are educated, in both academic and practice settings. Programs for basic preparation of health professionals were to undergo curriculum revision in order to focus on evidence-based quality improvement processes. Also, professional development programs would need to become widely available to update skills of those professionals who were already in practice. Leaders in all health disciplines were urged to come together in an effort for clinical education reform that addresses five core competencies essential in bridging the quality chasm: All health professionals should be educated to deliver patient-centered care as members of an interdisciplinary team emphasizing evidence-based practice, quality improvement approaches, and informatics (IOM, 2003). Table 4 presents details of each competency.

From: IOM Health Professions Education, 2003, p. 4. |

From this core set, IOM urged each profession to develop details and strategies for integrating these new competencies into education. With a focus on employing evidence-based practice, nurses established national consensus on competencies for EBP in nursing in 2004 and extended these in 2009 (Stevens, 2009). The ACE Star Model served as a framework for identifying specific skills requisite to employing EBP in a clinical role. Through multiple iterations, an expert panel generated, validated, and endorsed competency statements to guide education programs at the basic (associate and undergraduate), intermediate (masters), and doctoral (advanced) levels in nursing. Between 10 and 32 specific competencies are enumerated for each of four levels of nursing education which were published in Essential Competencies for EBP in Nursing (Stevens, 2009). These competencies address fundamental skills of knowledge management, accountability for scientific basis of nursing practice; organizational and policy change; and development of scientific underpinnings for EBP (Stevens, 2009).

A measurement instrument was developed from these competencies, called the ACE EBP Readiness Inventory (ACE-ERI). The ACE-ERI quantifies the individual’s confidence in performing EBP competencies. The ACE-ERI exhibits strong psychometric properties (reliability, validity, and sensitivity) and is widely used in clinical and education settings to assess nurses' readiness for employing EBP and measuring impact of professional development programs (Stevens, Puga, & Low, 2012). The ACE Star Model, competencies, and ERI have been adopted into practice settings as nurses strategize to employ EBP. These resources have also been incorporated into educational settings as programs are revised to include EBP skills.

Curricular efforts were also underway. To stimulate curricular reform and faculty development, the IOM suggested that oversight processes (such as accreditation) be used to encourage adoption of the five core competencies. Initiatives that followed included the new program standards established by the American Association of Colleges of Nursing, crossing undergraduate, masters, and doctoral levels of education (AACN, 2013). The AACN standards underscored the necessity for nurses to focus on the systems of care as well on the evidence for clinical decisions. This systems thinking is crucial to effect the changes that are part of employing EBP.

Another curricular initiative became known as Quality and Safety Education in Nursing Institute (QSEN) (QSEN Institute, 2013). Through multiple phases, this project developed a website that serves as a central repository of information on core QSEN competencies, knowledge, skill, attitudes, teaching strategies, and faculty development resources designed to prepare nurses to engage in quality and safety.

Educating nurses in EBP competencies was catapulted forward with the publication of Teaching IOM. Educating nurses in EBP competencies was catapulted forward with the publication of Teaching IOM (Finkleman & Kenner, 2006). While the materials presented were in existence in other professional literature, the book added great value by synthesizing what was known into one publication. This resource was accessible to every faculty member offering teaching strategies and learning resources for incorporating the IOM competencies into curricula across the nation. The resource continues to be updated and expanded through subsequent editions and versions (Finkleman & Kenner, 2013a; 2013b). The strength of these resources is that the approaches and strategies remain closely aligned with the Institute of Medicine’s continuing progress toward better health care. This close alignment reflects the appreciation that nursing must be part of this solution to effect the desired changes; and remaining in the mainstream with other health professions rather than splintering providers into discipline-centric paradigms.

Impact on Nursing Research

Nascent fields are emerging to understand how to increase effectiveness, efficiency, safety, and timeliness of healthcare; how to improve health service delivery systems; and how to spur performance improvement. Nursing research has been impacted by recent far-reaching changes in the healthcare research enterprise. Never before in healthcare history has the focus and formalization of moving evidence-into-practice been as sharp as is seen in today’s research on healthcare transformation efforts. Nascent fields are emerging to understand how to increase effectiveness, efficiency, safety, and timeliness of healthcare; how to improve health service delivery systems; and how to spur performance improvement. These emerging fields include translational and improvement science, implementation research, and health delivery systems science.

Investigation into uptake of evidence-based practice is one of the fields that has deeply affected the paradigm shift and is woven into each of the other fields. Investigation into EBP uptake is equivalent to investigating Star Point 4 (integration of EBP into practice). Several notable federal grant programs have evolved to foster research that produces the evidential foundation for effective strategies in employing EBP. Among the new research initiatives are the Clinical Translational Science Awards and the Patient-Centered Outcomes grants.

Clinical and Translational Science Awards

When the public cry for improved care escalated, rapid movement of results into care was brought into sharper focus in healthcare research. The National Institutes of Health (NIH), including the National Institute for Nursing Research (NINR), developed the Clinical Translational Science Award (CTSA) program to speed research-to-practice by redesigning the way healthcare research is conducted (Zerhouni, 2005). The term, translational science, was coined, and the definition was provided by NIH (2010): “Translational research includes two areas of translation. One [“T1”] is the process of applying discoveries generated during research in the laboratory, and in preclinical studies, to the development of trials and studies in humans. The second area of translation [“T2”] concerns research aimed at enhancing the adoption of best practices in the community. The comparative effectiveness of prevention and treatment strategies are [sic] also an important part of translational science” (Section I, para 2).

Nurses are involved in each of the 60 CTSAs that were funded across the nation... Nurse scientists have been significant leaders in the CTSA program, conducting translational research across these two areas. Nurses are involved in each of the 60 CTSAs that were funded across the nation, contributing from small roles and large roles, ranging from advisor and collaborator to principal investigator. As part of the CTSAs, nurse scientists conduct basic research and applied research, adding significantly to the interprofessional perspectives of the science. In relation to EBP, nurses are valued contributors to the “T2” end of the continuum of translational science, applying skills in mixed methods and systems settings.

Patient-Centered Outcomes Research

As evidence mounted on standard medical metrics...it was noted that metrics and outcomes of particular interest to patients and families... were understudied. Another recent and swooping change in healthcare research emerged with a focus on patient-centered outcomes research (PCOR). As evidence mounted on standard medical metrics (mortality and morbidity), it was noted that metrics and outcomes of particular interest to patients and families (such as quality of life) were understudied. In 2010, attention was drawn to the need to produce evidence on patient-centered outcomes from the perspective of the patient. Congress founded and heavily funded the newly-formed Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) with the following mission: “The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) helps people make informed health care decisions, and improves health care delivery and outcomes, by producing and promoting high integrity, evidence-based information that comes from research guided by patients, caregivers and the broader health care community” (PCORI, 2013, para. 1).

Likewise, some of the most recent calls for research from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) are also focusing on PCOR. These calls encourage early and meaningful engagement of patients and other stakeholders in stating the research question, conducting the study, and interpreting results (AHRQ, 2013). This new direction in healthcare research will produce evidence that is co-investigated by patients and families in partnership with health scientists, increasing relevance so that EBP reflects the patient’s viewpoint.

The Next Big Ideas

Two additional federal initiatives exemplify what may be called the next big ideas in EBP—each underscoring evidence-based quality improvement. The initiatives call for better use of the knowledge that may be gained from quality improvement efforts. Both initiatives emanate from the NIH and both focus on generating evidence needed to make systems improvements and transform healthcare. The first is NIH’s expansion of the program on Dissemination and Implementation (D&I) science; the second is the development of the research network, the Improvement Science Research Network (ISRN).

NIH Dissemination & Implementation (D&I) Grants

A call for increased emphasis on implementation of evidence-based practices brought forth a federal funding program. In January of 2013, the NIH initiative in dissemination and implementation was expanded across 14 institutes, including NINR. In this call for research proposals, implementation is defined as “the use of strategies to adopt and integrate evidence-based health interventions and change practice patterns within specific settings” (NIH, 2013, Section I, para 11). This research initiative will add to our understanding of how to create, evaluate, report, dissemination, and integrate evidence-based strategies to improve health (Brownson, Colditz, & Proctor, 2012). Because of the central role that nurses play across all healthcare settings and clinical microsystems, research in this field is highly relevant to the profession.

D&I research offers nurses opportunities to guide health care transformation at multiple level... This field of science moves beyond the individual provider as the unit of analysis and focuses on groups, health systems, and the community. D&I research offers nurses opportunities to guide health care transformation at multiple levels, thereby addressing recommendation from the Future of Nursing. For example, one emphasis in the field is discovering and applying the evidence for the most effective ways to speed adoption of evidence-based guidelines across all health care professionals in the clinical unit and in the agency. To date, nurse scientists are minimally engaged in D&I research. A recent survey of seven years of NIH projects indicated that only four percent of these were awarded to nurse scientists (Tinkle, Kimball, Haozous, Shuster, & Meize-Grochowski, 2013).

Improvement Science Research Network

The overriding goal of improvement science is to ensure that quality improvement efforts are based as much on evidence as the best practices they seek to implement. Continuing work with using the ACE Star Model as a framework laid a pathway to one of the “next big ideas:” to move from EBP to the study of strategies for achieving EBP (Stevens, 2012). In many instances, studies about single innovations on Star Point 4 were often not rigorous or broad enough to produce credible and generalizable knowledge (Berwick, 2008). As a new field, improvement science focuses on generating evidence about employing evidence-based practice, providing research evidence to guide management decisions in evidence-based quality improvement. The overriding goal of improvement science is to ensure that quality improvement efforts are based as much on evidence as the best practices they seek to implement.

Recognizing that pockets of excellence in safety and effectiveness exist, there is concern that local cases of success in translating research into practice are often difficult to replicate or sustain over time. Factors that make a change improvement work in one setting versus another are largely unknown. To fill this gap, the Improvement Science Research Network (ISRN) was developed (Stevens, 2010). The ISRN is an open research network for the study of improvement strategies in healthcare. The national network offers a virtual collaboratory in which to study systems improvements in such a way that lessons learned from innovations and quality improvement efforts can be spread for uptake in other settings. The ISRN was developed in response to an NIH call for projects that build infrastructures to advance new fields of science.

The ISRN supports rigorous testing of improvement strategies to determine whether, how, and where an intervention for change is effective. The following shortcomings in research regarding improvement change strategies have been noted: studies do not yield generalizable information because they are performed in a single setting; the improvement intervention is inadequately described and impact imprecisely measures; information about sustainability of change is not produced; contexts of implementation are not accounted for; cost or value is not estimated; and such research is seldom systematically planned (IOM, 2008b).

The primary goal of the network is to determine which improvement strategies work as we strive to assure effective and safe patient care. Through this national research collaborative, rigorous studies are designed and conducted through investigative teams. Foundational to the network is the virtual collaboratory, fashioned to conduct multi-site studies and designed around interprofessional academic-practice partnerships in research. The ISRN offers scientists and clinicians from across the nation opportunities to directly engage in conducting studies. “No hospital too small, no study too large” is one of the guiding principles of ISRN collaboration (ISRN Resource List, n.d., para. 28). ISRN Research Priorities were developed via stakeholder and expert panel consensus and are organized into four broad categories: transitions in care; high performing clinical microsystems; evidence-based quality improvement; and organizational culture (ISRN, 2010). The research collaboratory concept has proven its capacity to conduct multi-site studies and is open to any investigator or collaborator in the field.

The new NIH D&I grant resources and the ISRN collaboratory are “the next big ideas” in advancing EBP today. These will provide the scientific foundation for the rapidly expanding efforts to make healthcare better. Nurses will take advantage of these EBP advances to address opportunities and challenges.

Opportunities and Challenges

...the story of EBP in nursing is now long, with many successes, contributors, leaders, scientists, and enthusiasts. Much has been done to make an impact; much remains to be accomplished. From this admittedly selective overview of EBP, it is seen that the story of EBP in nursing is now long, with many successes, contributors, leaders, scientists, and enthusiasts. Much has been done to make an impact; much remains to be accomplished. Opportunities and challenges exist for clinicians, educators, and scientists.

Those leading clinical practice have willing partners from the academy for discovering what works to improve health care. Such evidence to guide clinical management decisions is long overdue (Yoder-Wise, 2012). While there are benefits to both as the evidence is gathered and applied, the true benefit goes to the patient. Clinical leaders have unprecedented opportunity to step forward to transform healthcare from a systems perspective, focusing on EBP for clinical effectiveness, patient engagement, and patient safety.

Those leading education have great advantages offered from a wide variety of educational resources for EBP. The rich resources offer students a chance to meaningfully connect their emerging competencies with clinical needs for best practices in clinical and microsystem changes. As they emerge from formal education, students will see great enthusiasm for employing EBP in today’s clinical environments.

Those leading nursing science have access to new funding opportunities to develop innovative programs of research in evidence-based quality improvement, implementation of EBP, and the science of improvement. Readiness of the clinical setting for academic-practice research partnerships brings with it advantageous access to clinical populations and settings and an eagerness for utilization of the research results.

The challenges for moving EBP forward spring from two sources: nurses becoming powerful leaders in interprofessional groups and nurses becoming powerful influencers of change. Therefore, adopting the following habits hold promise for moving us ahead:

- Redesigning and/or investigating the redesign of healthcare systems through creativity and mastery of teamwork.

- Persistence in educating the future workforce, and retooling the current workforce, with awareness, skills, and power to improve the systems of care.

- Laying aside comfortable programs of research and picking up programs of systems research.

- Insistence on multiple perspectives and sound evidence for transforming healthcare.

The nursing profession remains central to the interdisciplinary and discipline-specific changes necessary to achieve care that is effective, safe, and efficient. New in our vernacular and skill set are systems thinking, microsystems change, high reliability organizations, team-based care, transparency, innovation, translational and implementation science, and, yes, still evidence-based practice. Let us move swiftly to make these new ideas and skills commonplace.

Acknowledgment

Portions of this work were supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Nursing Research NIH (1RC2 NR011946-01, PI K. Stevens), and NIH CTSA (UL1TR000149, PI R. Clark).

Correction Notice

On September 3, 2013, the Acknowledgment was modified from the original publication date of May 31, 2013. Additional information has been added at the request of the author.

Author

Kathleen R. Stevens, EdD, RN, ANEF, FAAN

E-mail: STEVENSK@uthscsa.edu

Dr. Stevens is STTI Episteme Laureate, Professor and Director of the Academic Center for Evidence-Based Practice (ACE) and Improvement Science Research Network (ISRN) in the University of Texas Health Science Center School of Nursing San Antonio. She holds the UT System Chancellor’s Health Fellowship in interprofessional health delivery science. Her multi-site research on team collaboration and frontline engagement in quality improvement is conducted through the national collaboratory, the ISRN.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). (2013). Funding and grants. Retrieved from: www.ahrq.gov

© 2013 OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing

Article published May 31, 2013

References

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). (2008). TeamSTEPPS national implementation project 2008. Retrieved from: http://teamstepps.ahrq.gov/

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). (2013). Funding and grants. Retrieved from: www.ahrq.gov

American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN). (2013). Essentials series. Retrieved from: www.aacn.nche.edu/education-resources/essential-series

Berwick, D.M. (2008). The science of improvement. Journal of the American Medical Association, 299(10), 1182-1184.

Brownson, R.C., Colditz, G.A., & Proctor, E.K. (2012). Dissemination and implementation research in health: Translating science to practice. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc.

Finkelman, A & Kenner, CA. (2006). Teaching IOM: Implications of the IOM reports for nursing education. Washington, DC: American Nurses Association.

Finkelman, A & Kenner, CA. (2013a). (3rd Ed). Teaching IOM: Implications of the IOM reports for nursing education. Washington, DC: American Nurses Association.

Finkelman, A & Kenner, CA. (2013b). Learning IOM: Implications of the IOM reports for nursing education. Washington, DC: American Nurses Association.

Improvement Science Research Network (ISRN) (n.d.) ISRN resource list. Retrieved from www.isrn.net/ISRNResourceList

Improvement Science Research Network (ISRN). (2010). Research priorities. Retrieved from www.isrn.net/research

Institute of Medicine (IOM). (1990). Medicare: A strategy for quality assurance. (Lohr, KN, Ed.). Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Institute of Medicine. (2000). To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Institute of Medicine. (2001). Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. Washington DC: National Academies Press.

Institute of Medicine. (2003). Greiner, AC & Knebel, E (Eds.). Health professions education: A bridge to quality. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Institute of Medicine. (2008a). Knowing what works in health care: A roadmap for the nation. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Institute of Medicine (IOM). (2008b). Training the workforce in quality improvement and quality improvement research. IOM Forum Workshop. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Institute of Medicine. (2011a). The future of nursing: Leading change, advancing health [prepared by Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Committee Initiative on the Future of Nursing]. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Institute of Medicine. (2011b). Finding what works in health care: Standards for systematic reviews. [Committee on Standards for Systematic Reviews of Comparative Effective Research; Board on Health Care Services]. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Institute of Medicine. (2011c). Clinical practice guidelines we can trust [Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines]. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. Retrieved from: www.iom.edu/Reports/2011/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines-We-Can-Trust.aspx.

Institute of Medicine. (2013). Announcement. Crossing the quality chasm: The IOM health care quality initiative. Retrieved from: www.iom.edu/Global/News%20Announcements/Crossing-the-Quality-Chasm-The-IOM-Health-Care-Quality-Initiative.aspx

Mitchell, S.A., Fisher, C.A., Hastings, CE, Silverman, L.B., Wallen, G.R. (2010). A thematic analysis of theoretical models for translational science in nursing: Mapping the field. Nursing Outlook, 58(6), 287-300.

National Institutes of Health (NIH). (2010). Institutional clinical and translational science award (U54) Retrieved from: http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/RFA-RM-10-001.html#SectionI

National Institutes of Health (NIH). (2013). Dissemination and implementation research in health. PAR 10-038. Retrieved from: http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/PAR-10-038.html

Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). (2013). Mission and vision. Retrieved from: www.pcori.org/about/mission-and-vision/

Quality and Safety Education in Nursing Institue (QSEN). (2013). About QSEN. Retrieved from http://qsen.org/about-qsen/

Shojania, K.G., & Grimshaw, J.M. (2005). Evidence-based quality improvement: The state of the science. Health Affairs (Millwood), 24(1), 138-150.

Stevens, K.R. (2004). ACE star model of knowledge transformation. Academic Center for Evidence-based Practice. University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio. www.acestar.uthscsa.edu

Stevens, K.R. (2009). Essential evidence-based practice competencies in nursing. (2nd Ed.) San Antonio, TX: Academic Center for Evidence-Based Practice (ACE) of University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio.

Stevens, K.R. (2012). Delivering on the promise of EBP. Nursing Management, 3(3). Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, Inc.

Stevens, K.R., Puga, F., & Low, V. (2012). The ACE-ERI: An instrument to measure EBP readiness in student and clinical populations. Retrieved from: www.acestar.uthscsa.edu/institute/su12/documents/ace/8%20The%20ACE-ERI%20%20Instrument%20to%20Benchmark.pdf

Tinkle, M., Kimball, R., Haozous, E.A., Shuster, G., & Meize-Grochowski, R. (2013). Dissemination and implementation research funded by the US National Institutes of Health, 2005–2012. Nursing Research and Practice, Article ID 909606, 15 pages.

Yoder-Wise, P. (2012). The complex challenges of administrative research for the future. JONA, 42(5), 239-241.

Zerhouni, E.A. (2005). Translational and clinical science—time for a new vision. New England Journal of Medicine, 353(15), 1621-3.