Libraries are a primary resource for evidence-based practice. This study, using a critical incident survey administered to 6,788 nurses at 118 hospitals, sought to explore the influence of nurses’ use of library resources on both nursing and patient outcomes. In this article, the authors describe the background events motivating this study, the survey methods used, and the study results. They also discuss their findings, noting that use of library resources showed consistently positive relationships with changing advice given to patients, handling patient care differently, avoiding adverse events, and saving time. The authors discuss the study limitations and conclude that the availability and use of library and information resources and services had a positive impact on nursing and patient outcomes, and that nurse managers play an important role both by encouraging nurses to use evidence-based library resources and services and by supporting the availability of these resources in healthcare settings.

Keywords: Evidence-based nursing, nursing care, nursing outcomes, library services, online databases, information technology, information services, information use, information resources, quality of care, survey research, multivariate analysis

Summary

Libraries provide essential resources for literature searches and access to open source and other forms of research-based knowledge in healthcare settings. A previous letter to the editor of OJIN (Guild, 2013) emphasizes the importance of comprehensive literature searches and open access publications for evidence-based practice and quality outcomes. Libraries provide essential resources for literature searches and access to open source and other forms of research-based knowledge in healthcare settings. Although nurses have been encouraged to use research-based information resources since the 1970s (Estabrooks, 2009), recent movements in clinical practice have placed even greater importance on the need to access the ‘best evidence.’ Evidence-based practice emphasizes the use of the best available research evidence in conjunction with clinical expertise and patient preferences (Sackett, 2000). Research has shown both that evidence-based practice improves quality of care and reduces costs, and that nurse managers play important roles in encouraging the adoption of evidence-based nursing (Dogherty & Harrison, 2012; Grimshaw et al., 2006; Solomons & Spross, 2011). In response to this movement, efforts to increase nurses’ awareness of the benefits of integrating research literature into their clinical decisions have been renewed (Melnyk, Fineout-Overholt, Stillwell, & Williamson, 2009; 2010). The rise of Magnet® hospital recognition has provided additional incentives for the provision and use of evidence-based resources.

A series of consensus reports by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) has also provided strong arguments supporting the use of research literature by healthcare professionals. In 2001, the IOM report, Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century, called for the implementation of interdisciplinary healthcare teams that focus on delivery of evidence-based patient care (IOM, 2001). A more recent report, Knowing What Works in Health Care: A Roadmap for the Nation, explicitly stated that access to “…unbiased, reliable information about what works in health care is essential to addressing several persistent health policy challenges…” (p. 3), including the improvement of healthcare quality and constraint of healthcare costs (IOM, 2008).

However, participation in evidence-based practice is still relatively new in nursing. Earlier studies of nurses’ information-seeking behaviors suggested that nurses as a group are unlikely to be consistent users of research journals and other evidence-based resources, preferring information obtained through ‘social means’ over that obtained from scholarly sources. For example, Marshall, West, and Aitken (2010) found that critical care nurses, when faced with a clinical question, were most likely to value and use information obtained from consultations with colleagues, while electronic and print resources, found mainly in libraries, were significantly less preferred options Similar findings have been noted by other researchers (Estabrooks, Chong, Brigidear, & Profetto-McGrath, 2005; Profetto-McGrath, Smith, Hugo, Taylor, & El-Hajj, 2007).

Nurses have typically attributed their undervaluing of evidence-based resources to a lack of accessibility... Nurses have typically attributed their undervaluing of evidence-based resources to a lack of accessibility, including limited physical access to information resources, the skills to understand and utilize information accessed, and/or insufficient time to seek out research and incorporate it into clinical practice (French, 2005; Marshall et. al, 2010; Thompson, McCaughan, Cullum, Sheldon, & Raynor, 2005). The purpose of our research was to build on earlier studies by exploring practicing nurses’ use of evidence-based-information resources provided by libraries and its relationship to nursing and patient outcomes. In this article, we will describe the background events motivating this study, the survey methods, and the study results. We will also discuss our findings, note the study limitations, and conclude that the availability and use of library and information resources and services had a positive impact on nursing and patient outcomes.

Background to the Study

In 2007, the National Network of Libraries of Medicine, Middle Atlantic Region (NN/LM MAR), a region that includes the states of Delaware, New Jersey, New York (NY), and Pennsylvania, created a planning group of librarians from a variety of healthcare settings to investigate the possibility of replicating an earlier study conducted in the Rochester, NY area regarding the value and impact of hospital library services on clinical care (Marshall, 1992). In the Rochester Study, those physicians and residents who requested from their hospital librarian a MEDLINE search related to a current clinical case reported substantial impacts of the search on clinical decision making and patient care outcomes. The planning group for the NM/LM MAR study recognized the growing trend towards evidence-based nursing and decided that physicians, residents, and also nurses should be included in the replication. The NN/LM MAR study took into account changes in technology and information access methods that had occurred since the Rochester study, by focusing on the potential impact of direct searching of electronic information resources by health professionals themselves, as well as use of those intermediary search services provided by the librarian. The NN/LM MAR planning group envisioned a multisite study that would allow participation by a range of health professionals located in varying types and sizes of institutions in different geographic locations.

The NN/LM MAR study used a Community Based Participative Research (CBPR) approach, in which both researchers and members of the community that will benefit from the research play an equal part. CBPR has been used extensively in the healthcare field (Israel, Eng, Schulz, & Parker, 2005) as a means of ensuring that research is relevant to the needs of the prospective audience. This approach also ensures that methods used to gather data are practical and achievable. The CBPR was then implemented by establishing a ten-member planning group that included librarians from different types of healthcare delivery settings. Members of the planning group participated in all aspects of study design, survey development, and site recruitment.

The NN/LM MAR study also employed the Critical Incident Technique (CIT) in which the health-professional respondents were asked to base their answers on a specific clinical situation in which they had sought out information using library and information resources and services. This technique has been found to increase respondent recall and the accuracy of responses. In CIT research, the ability of the researchers to gather enough critical incidents to identify major trends in the data is the major factor in determining validity (Butterfield, Borgen, Amundson, & Maglio, 2005). In our study (described below), an exceptionally large number of critical incidents were collected. There were 5,379 eligible responses from physicians, 2,123 from residents, and 6,788 from nurses. The large respondent pool made it possible for us to examine sub-groups within the data and to investigate results in a way that would not have ben possible in a smaller study.

Survey Methods

This section contains an overview of the survey instrument, sample, and data collection methods, including site selection and recruitment. A discussion of the measures used and the multivariate analysis of the nursing data are also included. An earlier article by Marshall et al. (2013) provides a more detailed account of the methods, as well as the descriptive findings of the full study of physicians, residents, and nurses.

Survey Instrument

In the web-based survey, health professionals were given the following instructions: “Think of an occasion in the last 6 months when you looked for information resources for patient care (beyond what is available in the patient record, electronic medical record [EMR] system, or lab results). Please answer the following questions regarding this occasion.” Respondents were then asked about the patient’s diagnosis; type of information needed; information resources used, information access points; quality and completeness of information retrieved; as well as the patient care outcomes of using the information obtained. The survey also included questions related to the health professional’s role, including factors such as how many years the respondent had worked as a health professional and educational attainment. Each web page contained the study name, “Value and Impact of Library and Information Services in Patient Care Study,” so that respondents were reminded about the focus of the research.

Sample

Study sites were recruited by the National Network of Libraries of Medicine, Middle Atlantic Region (NN/LM MAR) and by members of the study planning group through an invitation to all the libraries on their email list. Libraries did not have to be a member of NN/LM MAR to participate in the study. Once a site’s eligibility was determined by the researchers at the University of North Carolina (UNC), the library director was asked to complete an online profile that described the library’s users, staffing, budget, collections, and services. In order to participate, the libraries had to provide services to health professionals who were involved in direct patient care. Librarians also had to agree to make the study invitation available to physicians, residents, and nurses in their setting and to promote participation. Special efforts were made to recruit different types and sizes of hospitals. These methods resulted in a sample of 56 library sites that served health professionals at 118 hospitals. The UNC Institutional Review Board approved the study after reviewing all study procedures. The survey was anonymous and no personally identifying information was gathered. Participation was voluntary. Informed consent was implied when the health professional chose to respond to the survey.

Individual respondents at each site were recruited through listservs or the institution’s intranet, depending on the typical means used to communicate with all physicians, residents, and nurses at that institution. The survey achieved a response rate of 10%. This is likely an underestimated rate because only those healthcare providers who were involved in patient care or clinical research, and who had used the library and information services for seeking information related to patient care in the previous six months were eligible to participate. Those who began the survey and were found to be ineligible because they were not involved in patient care were removed from the denominator (which was based on the total number of physicians, residents, and nurses at the hospital). However, there may be others who did not start the survey at all because they had noted earlier the criteria for inclusion. Another factor that should be taken into account when interpreting the response rate is that the validity of CIT studies is judged primarily by the ability of the researchers to obtain a sufficiently large number of critical incidents to determine consistent trends in the data.

...6,788 nurses, who identified patient care as at least part of their current job role, and who had used the library for seeking information related to patient care, completed the survey. Of the 19,234 responses, 2,290 were deemed ineligible as the responders were not involved in either patient care or clinical research; and 826 people did not complete enough of the survey to be included. Of the remaining eligible cases, 6,788 nurses, who identified patient care as at least part of their current job role, and who had used the library for seeking information related to patient care, completed the survey. This analysis is restricted to those nurse respondents. Full details of the survey sample, site and respondent recruitment, data collection methods, and descriptive results have been reported elsewhere by Marshall, et al. (2013).

Data Collection

A pilot study was conducted to ascertain the effectiveness of survey content, structure, and delivery method. The pilot test was conducted at seven sites that were members of the NN/LM MAR. A call for participation by sites outside NN/LM MAR was sent via relevant health library listservs. Additional recruitment efforts included a webinar and presentations at regional meetings. One hundred and twenty library sites initially expressed interest in the study. Of these interested sites, four were ineligible because they did not provide library services for clinicians and eight cases were duplicates (i.e., multiple staff members at a library had expressed an interest). Forty-nine libraries participated in this pilot phase of the study. Data from the pilot and the full launch were combined in the data analysis as the survey did not require major revisions between the two waves of data collection.

Measures

The survey questions and outcome measures from the original Rochester study (Marshall, 1992) were reviewed by the study planning group and revised to reflect the current information access and healthcare environments. Since the time of the original study, electronic access to library resources had steadily increased, with databases and full text articles being available electronically in healthcare settings in both clinical and research areas.

In the analysis reported here, we identified four key outcomes relevant to nursing and patient care to provide an assessment of the impact of the use of the library and information resources. The first outcome was created to predict the amount of time saved as a result of the information obtained in the respondents' searches. This variable was created from a survey question that read, “Recalling the [clinical situation], please indicate whether you agree or disagree with the following: Having the information saved me time.” If respondents agreed with this statement they were asked how much time they had saved in minutes and hours. Time saved that was reported in minutes was converted to hours using decimal points as needed.

...the researchers identified two additional outcomes that are particularly relevant to nursing care: whether the nurses had changed the advice they gave to the patient and whether they had handled the patient care situation differently. The second outcome was a summary variable measuring the number of reported adverse events avoided as a result of the information found in the respondent's search. The survey question read, “Recalling the same [patient care situation], did any of the following change in a positive way as a result of the information?” The respondents were then presented with a list of 12 possible adverse events: hospital admission, hospital readmission, patient mortality, language or cultural misunderstanding, patient misunderstanding of disease, hospital acquired infection, surgery, regulatory non-compliance, additional tests or procedures, medication error, adverse drug reaction or interaction, and misdiagnosis. An option was given to list another adverse event not on the list. The researchers counted the number of adverse events that respondents reported avoiding, and then they computed a summary variable from that total.

Finally, the researchers identified two additional outcomes that are particularly relevant to nursing care: whether the nurses had changed the advice they gave to the patient and whether they had handled the patient care situation differently. These outcomes were measured using the following question: Recalling the [patient care situation], please indicate whether you agree or disagree with the following statements about the information you used. As one respondent said, “I was able to give better advice to the patient because I was better informed.” Another respondent noted, “the [library] information helped us prescribe the right medication – or, more importantly, prevented prescribing the wrong one.” The respondent added, “I think it is mostly a patient safety thing, so [the library information] makes me deliver safer care.”

The following control variables were tested in initial analyses but were excluded from the final multivariate model because they did not contribute significantly to the explanatory power of the model: age, gender, location of hospital (urban, suburban, or rural), annual expenditures on electronic resources, annual expenditures of the library, and whether the library staff offered instructional programs. It should be noted that because budgets are often affected by the consortium arrangements used by libraries to reduce costs, the actual cost of information resources may not show up in individual hospital library budgets. Also, almost all libraries offered instructional programs.

...because budgets are often affected by the consortium arrangements used by libraries to reduce costs, the actual cost of information resources may not show up in individual hospital library budgets. How the respondents accessed information was operationalized using four access methods: (a) whether they asked a librarian for help with the information search; (b) whether they performed the search in a physical library; (c) whether they used the library’s website; and (d) whether they used the institution’s intranet. At some sites, health professionals accessed the library’s information resources via a separate library website. At other sites, the library resources were accessed via the institution’s intranet.

The information resources and services available at each site were operationalized using the following measures: (a) the number of full-time equivalent (FTE) library staff available at the hospital; (b) the number of FTE professional master’s degree librarians; (c) the number of electronic databases and other types of information resources available; and (d) the number of library-provided information resources respondents reported using for their search, such as Micromedex, PubMed MEDLINE, online books and journals, UpToDate, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and Nursing Reference Center. The nurses reported using an average of 2.8 (S.D. 2.2) different library resources in their search. The nurses selected the resources from a list of library resources included in the survey; however, an option was given to add additional sources that were not on the list.

The nurses reported using an average of 2.8 different library resources in their search. Respondents were also asked how they accessed resources. While a third of the nurses reported using Google to access at least one resource, almost 90% reported using the library website or the institution’s intranet. It is common for Google searches to be used as a quick way to identify a relevant publication. The point-of-care information resource, UpToDate, was also used frequently as a ‘first place to look.’ UpToDate is a commercially available database that is marketed as an ‘evidence-based, clinical-decision-support resource.’ It contains peer reviewed, referenced summaries on a wide range of clinical topics, as well as patient education articles and other materials. The use of such tools is often followed by a search of additional library resources to access the full text of referenced articles or other relevant materials on the topic in the library collection. Many journals make their full text articles available only by subscription, which makes use of the library essential. Library staff members also provide assistance in navigating the increasingly complex world of electronic information and locating items that are difficult to find.

Level of education and tenure as a healthcare professional were used as control variables, as were key characteristics of hospitals where the nurses were employed. These variables included dichotomous indicators of whether the hospital had Magnet®status, was a member of the Council of Teaching Hospitals, and bed size. See Table 1 for further elaboration of the dependent variables and the descriptive statistics.

Multivariate Analysis

The analytic strategy was designed to assess the relative impact of using the physical library and library-provided electronic resources for information seeking related to patient care on key outcome measures. Four separate models, two using Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression for the continuous variables, and two models using logistic regression for the dichotomous variables, formed the basis for the analysis. These types of multivariate analyses allow the researcher to assess the strength and direction of the impact of independent variables while controlling for the other variables in the model. These model types were chosen as appropriate to the level of analysis of the dependent measures.

Ordinary least squares (OLS) regression is appropriate for use with continuous variables. These measures are counts that approximate a normal distribution given their range and descriptive characteristics. These were chosen over logistic regression for the first two outcome measures (time saved and number of adverse events avoided), as dichotomizing the outcomes would have resulted in the loss of valuable information on how much impact could be seen on the dependent variable. The other two models (changed advice given to the patient and handled the situation differently) were based on dichotomous ‘agree’ or ‘disagree’ responses; therefore logistic region was used.

The researchers also identified workplace and respondent characteristics that might potentially influence information-seeking behavior as control variables. By holding these variables constant, we could assess the impact of the independent variables of interest. The control variables included: how long the respondent had worked as a healthcare professional; level of nursing education; whether they were affiliated with a Magnet® hospital; whether their hospital was a member of the Council of Teaching Hospitals (COTH); the bed size of their largest affiliate hospital; and which access method was used to conduct their information search. Holding these characteristics constant, the authors operationalized the following concepts: (a) how nurses accessed the information, and (b) the number of information resources that the library made available to nurses in their workplace.

Multivariate Results

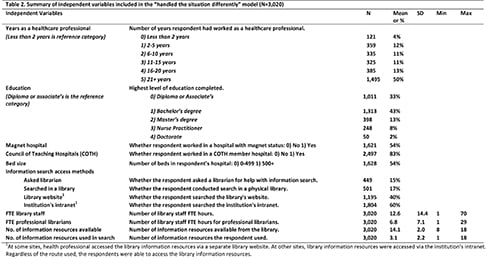

For the methodology and overall results of the full study, readers are referred to the article by Marshall et al. (2013). Because the results across all the multivariate models were similar, we have decided to present the descriptive findings for the ‘handled the situation differently’ model in Tables 1 and 2, as the analytic sample for this model had the largest number of respondents. Only nurses who had answered all the questions used in the analysis were included, which accounts for the reduced number of respondents. Table 1 provides a description of the dependent variables used in the model, and Table 2 provides a description of the independent variables. Both tables include the number of respondents and the mean or percent, as appropriate for the type of measurement. For means, the standard deviation and the minimum and maximum values are shown

Independent Variables

The independent variables used in the analysis of the nurses’ data are summarized below. Numbers of respondents are shown in Table 2.

Years as a healthcare professional. Four percent of the participants had worked as a healthcare professional for less than two years, 12% between 2 and 5 years, 11% between 6 and 10 years, 11% between 11 and 15 years, 13% between 16 and 20 years, and 50% more than 20 years.

Hospital characteristics. Over half of the nurses reported working at a Magnet® hospital. More than 80% of the nurses were affiliated with a Council of Teaching Hospitals (COTH) member hospital, and slightly more than half worked in hospitals with more than 500 beds.

Information search access points. Fifteen percent of the nurse respondents reported asking a librarian for assistance during their information search, 17% conducted their search in a physical library. Forty percent used the library website, and 60% used their institution’s intranet. Sites varied in the way that access was provided to the library information resources. Both of these routes could have been used to access the library resources or services. It is possible that the nurses may have guessed about whether they were accessing information via one or the other method, since the difference is not always obvious.

Library staff. The mean number of full-time equivalent (FTE) library staff was 12.6. The mean number of FTE professional librarians was 6.8.

On average, respondents had access to 14.1 library information resources in the participating institutions. Information resources. On average (mean value), respondents had access to 14.1 library information resources in the participating institutions.

These above findings indicate that the respondent group was not fully representative of the general nursing population in that respondents tended to be more experienced nurses who were likely to work in teaching hospitals. Slightly over half of the respondents worked in Magnet® hospitals with over 500 beds. On the other hand, there was considerable geographic spread among the participating sites. Given the nature of the study, it may not be surprising that the larger teaching hospitals and Magnet® hospitals (which also had more library and information services staff) were more likely to participate in the study. A comparison of respondents who worked at libraries that were members of the Association of Academic Health Sciences Libraries (AAHSL) (N=21) and those that were not members (N=35) did not show major differences in outcome measures between the two groups.

Dependent Variables

The models predicting the two continuous dependent outcome variables are shown in Table 1. The results of the analyses are described below.

Time saved. Over 80% of the nurses indicated that having the information saved them time. The amount of time saved varied considerably with a mean of over two hours and a median of one hour. Over 80% of the nurses indicated that having the information saved them time. This variation in time saved is shown by the standard deviations in Table 1. The web survey did not ask whether the information search was done on work time or personal time or whether reported time saved was work time. However, given that the information search was directly related to patient care, and that nurses had access to the library electronic resources on the clinical unit, it seems likely that the time saved would have been work time. Table 3 indicates that the significant predictors of the amount of time saved by nurses as a result of the information found in their search were (in order of largest to smallest effect): (a) having asked a librarian for help in one’s information search; (b) working in a COTH hospital; (c) working in a larger-bed-size hospital; and (d) using a number of different library resources in the respondent’s search. Nurses who reported asking a librarian for help with their information search reported saving, on average, more hours than those who did not ask a librarian for assistance. Furthermore, the nurses who used a greater variety of information resources reported more time saved. These findings suggest that a broader range of information resources provided by the library can make a positive difference in outcomes.

The two significant predictors of change were using the institution’s intranet and the number of resources used in the search. Changed advice given to patients. This model predicted whether nurses changed the advice they gave to patients as a result of information obtained. The results of the logistic regression used for this and the ‘handled the patient care differently’ model are described here rather than in a separate table. The two significant predictors of change were using the institution’s intranet and the number of resources used in the search. While it is possible that the nurses who used the institution’s intranet could have found other useful information on the intranet, the researchers took care to indicate on each page of the web-based survey that the focus of the study was on the use of library and information resources. This approach increased the likelihood that the nurses would use the library and information resources as part of their search.

Handled the patient care situation differently. In this model, there were several significant predictors. The predictors included the following control variables: (a) having a Bachelor’s degree (as opposed to an Associate degree or Diploma qualifications); (b) having a Master’s degree (again in relation to Associate or Diploma qualifications); (c) having more than 11 years of experience as a healthcare professional; and (d) working in a larger-bed-size hospital. Having used more library resources in the search was associated with a 19% greater likelihood of handling the situation differently.

There are a number of similarities between the four models that point to the importance of libraries and library-related electronic resources to nursing care in hospitals. The number of sources used in the information search had a consistently positive relationship to all dependent variables. Consulting more information resources was significantly associated with saving more time and avoiding more adverse events as a result of having the information obtained in the search. The access method used for the information resources was also significant in three of the four models; having access to information resources provided through library-maintained, staff-supported locations was associated with positive outcomes. This is in fairly stark contrast to the effect of the hospital characteristics measured in these analyses, which have small and inconsistent effects in the models.

Avoidance of adverse events. Table 3 indicates that significant predictors of the number of adverse events avoided as a result of the respondent’s information search were (in order of largest to smallest effect): (a) being a nurse practitioner; (b) having conducted one’s search in a physical library or using the institution’s intranet; (c) having used more information resources in the search; and (d) having more library resources available for searching. Given both the level of responsibility of nurse practitioners and their key role in primary care, it is not surprising that nurse practitioners were more likely to report avoiding adverse events. Nurses who conducted their information search in a physical library reported avoiding more adverse events than did those who did the search on their own using the institution’s intranet. Finally, as noted above, nurses who used more resources in their search also reported avoiding more adverse events, as did the nurses who had more library information resources available to them.

|

Table 1. Summary of dependent variables included in the “handled the situation differently” model (N=3,020) |

||||||

|

Dependent Variables |

|

N |

Mean |

SD |

Min |

Max |

|

|

Recalling the [clinical situation], please indicate whether you agree or disagree with the following statements about the information you used. 1) Agree 0) Disagree or N/A. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Time saved |

Having the information saved me time (hours). |

1,991 |

2.3 |

6.9 |

.02 |

100 |

|

Changed advice given to patient |

Changed the advice given to patient or family. |

1,553 |

51% |

|

|

|

|

Handled situation differently |

Handled the situation differently. |

694 |

23% |

|

|

|

|

No. of adverse events avoided |

A total of 13 possible adverse events were listed in the survey. |

3,009 |

0.8 |

1.1 |

0 |

11 |

Table 2. Summary of independent variables included in the “handled the situation differently” model (N=3,020)

|

Table 3. Models predicting outcome variables (OLS Regression models for continuous dependent variables) |

||

|

|

(1) |

(2) |

|

Time saved |

No. of adverse events avoided |

|

|

Education |

|

|

|

(Diploma or associate is the reference category) |

||

|

Bachelor’s degree |

0.0169 |

0.0737 |

|

(0.353) |

(0.0468) |

|

|

Master’s degree |

0.372 |

0.114 |

|

(0.503) |

(0.0680) |

|

|

Nurse Practitioner |

0.457 |

0.442*** |

|

(0.579) |

(0.0809) |

|

|

Doctorate |

1.662 |

0.317 |

|

(1.212) |

(0.162) |

|

|

Years as a healthcare professional |

||

|

(Less than 2 years is the reference category) |

||

|

2-5 years |

0.425 |

0.0787 |

|

(0.843) |

(0.115) |

|

|

6-10 years |

0.573 |

-0.0613 |

|

(0.849) |

(0.116) |

|

|

11-15 years |

0.459 |

-0.103 |

|

(0.856) |

(0.117) |

|

|

16-20 years |

0.403 |

-0.137 |

|

(0.846) |

(0.114) |

|

|

More than 20 years |

0.664 |

-0.147 |

|

(0.766) |

(0.104) |

|

|

Magnet hospital |

0.0210 |

-0.0620 |

|

(0.320) |

(0.0431) |

|

|

Council of Teaching Hospitals (COTH) |

-1.021* |

-0.111 |

|

(0.435) |

(0.0575) |

|

|

Bed size |

0.777* |

0.0756 |

|

(0.323) |

(0.0428) |

|

|

Information search access methods |

||

|

Asked librarian |

1.980*** |

0.0284 |

|

(0.473) |

(0.0642) |

|

|

Searched in a library |

0.625 |

0.248*** |

|

(0.438) |

(0.0599) |

|

|

Used library website |

0.505 |

-0.00507 |

|

(0.338) |

(0.0457) |

|

|

Used institution's intranet |

-0.441 |

0.177*** |

|

(0.322) |

(0.0429) |

|

|

FTE library staff |

0.0887** |

0.00126 |

|

(0.0333) |

(0.00442) |

|

|

FTE professional librarians |

-0.182** |

0.00209 |

|

(0.0700) |

(0.00934) |

|

|

No. of information resources available |

0.127 |

0.0380** |

|

(0.0901) |

(0.0121) |

|

|

No. of information resources used in search |

0.481*** |

0.0903*** |

|

(0.0839) |

(0.0113) |

|

|

Constant |

-1.532 |

-0.138 |

|

(1.452) |

(0.195) |

|

|

Observations |

1,991 |

3,009 |

|

R-squared |

0.085 |

0.092 |

|

Standard errors in parentheses |

||

|

*** p<0.001, ** p<0.01, * p<0.05 |

||

Discussion

It is clear from the study results that nurses who used the library resources found them to be valuable in patient care. Nurses also reported using a wide range of electronic and print information resources, such as Micromedex, PubMed/Medline, online and print books, and UpToDate, in addition to the nursing-oriented databases such as Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) and Nursing Reference Center In many cases, nurses were using the same information resources as physicians and residents.

...access to and use of library-provided information resources had positive relationships with key nursing and patient outcomes... Separate multivariate analyses revealed that access to and use of library-provided information resources had positive relationships with key nursing and patient outcomes, including changes in advice given to patients, handling patient care situations differently, avoiding of adverse events, and saving time. Although the study did not gather extensive detail on the nature of these situations, our findings suggest that more in-depth, qualitative research would provide additional useful insights regarding the value of library and information services in nursing and patient care. It is notable that using the physical library and asking the librarian for assistance were among the variables that predicted the greatest number of positive outcomes.

In the survey, respondents were asked to indicate the principal diagnosis of the patient for whom their information search was related. They were also asked to indicate the type of information required, such as drug or therapy information, diagnosis, prognosis, information for the patient, adverse events, patient safety, and clinical guidelines. The healthcare providers were able to check as many of the responses as applied in the particular patient care situation. Due to space limitations in the survey and patient confidentiality, no further detail about the clinical situation was gathered as part of this study. Although a more detailed description of these situations would have provided a greater understanding of the process of changing the advice given to the patient, handling the situation differently, avoiding adverse events, and saving time, this was beyond the scope and resources of the current study. The improved outcomes found in our study suggest that further research to explore such situations in greater depth is warranted.

Limitations

As in all studies, there are limitations to this research. First, the sampling design was not a probability sample, since all affiliated healthcare providers who were involved in direct patient care or clinical research in the recruited hospitals and healthcare systems were eligible to participate. The researchers were able to determine that the demographic characteristics of the respondent group of physicians, residents, and nurses approximated the proportions of those professions in the broader population. While this does not indicate representativeness, it does suggest similarity. The nurses who responded to the survey were more likely to have a university degree and a greater number of years of experience. It is not surprising that more highly educated and experienced staff would be among the earliest adopters of evidence-based practice and more likely to engage in library information searching related to patient care. However, the results should not be taken as representing all nurses.

Sites were recruited for the study through the National Network of Libraries of Medicine, which is a comprehensive network of health sciences libraries across the country. In Canada, recruitment was done through the Canadian Health Libraries Association. While the researchers attempted to recruit healthcare settings with a range of bed sizes, as well as urban and rural locations, the 59 participating sites tended to be larger institutions in urban areas. Most sites were members of the Council of Teaching Hospitals (COTH). The researchers found that site participation was also influenced by factors, such as the ability of the librarian to obtain institutional support for participation and ethics approval, as well as having enough library staff available to administer and promote the study in the institution.

Another important limitation is that the results are based on self-reported views of the respondents. Over time, it will be important to seek out additional forms of data to verify the type of changes reported in this study.

In survey research, a response rate of 10% is considered to be low; however, this rate is mitigated by the large number of respondents and the use of the Critical Incident Technique (CIT), which relies on gathering a sufficient number of critical incidents to determine trends in the data. The consistent trends found in the data for different professional groups and different healthcare settings suggest that experiences similar to those reported in this study are likely to occur among other healthcare providers when they make use of library resources.

Future research on nursing and patient outcomes should include information use measures in addition to clinical level variables... Another limitation of our study is that, although we see significant impact of library and information resources on nursing and patient outcomes, there are many other factors that contribute to these particular outcomes. Future research on nursing and patient outcomes should include information use measures in addition to clinical level variables to increase the explanatory power of the model.

Although our findings are not generalizable to all nurses working in all hospitals, it is clear from the analysis presented in this study that relationships among variables exist. Despite this lack of generalizability, the study is rich in organizational, library, and individual context and the number of respondents was very large. Our multi-level context was important in understanding the value of libraries and library services in healthcare.

Conclusion

The findings of this study have important implications for nursing management. Specifically, study findings support the need for nurse managers, and other experienced nurses, to advocate for the accessibility of library resources, staff, and services for practicing nurses. This may mean supporting increased budgetary resources to maintain or expand health library collections, providing Internet and intranet access to nurses at the bedside, and investing in continuing education for nurses that will maximize the appropriate use of evidence-based information from the research literature. Additionally, as noted earlier, nurse managers and experienced nurses have important leadership roles in facilitating the adoption of evidence-based nursing practice.

Acknowledgement

This project was funded in part with Federal funds from the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract No. N01-LM-6-3501, New York University Medical Center Library and Contract No. HHS-N-276-2011-00003-C, University of Pittsburgh, Health Sciences Library System. Additional support was provided by the: Hospital Library Section, Medical Library Association (MLA); NY/NJ Chapter, MLA; Philadelphia Chapter, MLA; Upstate NY and Ontario Chapter, MLA; NY State Reference and Research Library Councils; and the Donald A.B. Lindberg Research Fellowship from MLA. The data, survey and all supporting documentation for the study are available at the study website http://nnlm.gov/mar/about/value.html.

Author

Joanne Gard Marshall, PhD, MLS, MHSc

Email: marshall@ils.unc.edu

Dr. Marshall is an Alumni Distinguished Professor in the School of Information and Library Science at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill where she served as Dean from 1999 to 2004. In addition to a PhD in public health, she has her master’s degrees in health sciences (clinical practice) and in library science. Dr. Marshall was principal investigator of the study upon which this article was based. Her major research interests include health information seeking and use; the value and impact of library and information services; and workforce issues in library and information science. Dr. Marshall has received research funding from the Institute of Museum and Library Services; the National Library of Medicine; Libraries for the Future; Health Canada; and the Ontario Ministry of Health. She has received awards for her research and service from the Medical Library Association; Canadian Health Libraries Association; and Special Libraries Association. She has been consulted by the British Library, Health Canada, and other research projects funded by the Institute of Museum and Library Services. She has been an Associate Research Fellow at the National Library of Medicine

Jennifer Craft Morgan, PhD

Email: jmorgan39@gsu.edu

Dr. Morgan is an assistant professor at the Gerontology Institute of Georgia State University in Atlanta, GA. She served as a methodology and statistical consultant for the study on which this paper is based. Her primary research interest is in workforce studies within healthcare organizations. She has led five major, funded projects evaluating the impact of career ladders, continuing education, and financial incentive workforce development programs on healthcare worker outcomes, quality of care outcomes, and perceived return on investment for healthcare organizations and educational partners. Dr. Morgan currently teaches graduate courses in research methods and the graduate capstone experience. She has published and presented widely in both scholarly and practice-based settings. Her work seeks to tie research, education, and service together by focusing on the translation of lessons learned.

Mary Lou Klem, PhD, MLIS

Email: klem@pitt.edu

Dr. Klem is a faculty librarian in the Health Sciences Library System (HSLS), University of Pittsburgh. She served on the planning committee for the study on which this article is based. For the past six years, she has served as the HSLS liaison to the University of Pittsburgh’s School of Nursing, providing BSN and graduate students with in-class and online instruction in information literacy, as well as basic and advanced database search techniques She has worked with nursing faculty to incorporate evidence-based practice (EBP) into the classroom, and has collaborated in the design and conduct of systematic reviews completed by nursing faculty. In addition to her work at the School of Nursing, Dr. Klem has served as a member of evidence-based nursing councils at both the hospital and system-wide levels in the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. During her time on these councils, she provided advanced training to clinical nurses and nursing administrators in literature search techniques, assisted in developing an EBP research fellowship program for clinical nurses at Presbyterian Hospital, and provided training and mentoring of successful applicants to the program.

Cheryl A. Thompson, MSIS

Email: ct.annette@gmail.com

Ms. Thompson is a doctoral student at the Graduate School of Library and Information Science, University of Illinois in Champaign, IL, and a Research Assistant at their Center for Informatics Research in Science and Scholarship. Prior to entering a doctoral program, Ms. Thompson had over 10 years of experience in social research and data management. She served as a data manager and project manager for the study on which this paper is based. In these roles, Ms. Thompson has worked with investigator scientists to design and implement systems for data collection and management. She has also provided training in data management, preparing Institutional Review Board applications, research tools, and data archiving. Ms. Thompson's detailed knowledge of methodology and data collection made her a valuable contributor to this paper.

Amber L. Wells, MA

Email: awells82@email.unc.edu

Ms. Wells is a doctoral student in sociology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill who has expertise in quantitative analysis Her research interests focus on understanding the ways in which work opportunities and career trajectories are stratified by gender and class. Ms. Wells played an important role in the data analysis for this paper as well as in the description of analytic methods. She also provided advice on the conclusions that can draw from the statistical methods employed in the analysis for this paper.

Article published August 18, 2014

References

Butterfield, L.D., Borgen, W.A., Amundson, N.E., & Maglio, A. (2005). Fifty years of the critical incident technique 1954-2004 and beyond. Qualitative Research 5(4), 475-97.

Dogherty, E.J. & Harrison, M.B. (2010). Facilitation as a role and process in achieving evidence-based practice in nursing: A focused review of concept and meaning. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 7 (2), 76-89. doi: 10.111/j.1741.6787.2010.00186.x

Estabrooks, C. A., Chong, H., Brigidear, K., & Profetto-McGrath, J. (2005). Profiling Canadian nurses' preferred knowledge sources for clinical practice. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 37(2), 118-140.

Estabrooks, C.A. (2009). Mapping the research utilization field in nursing. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 41(1), 218-236.

French, B. (2005). Contextual factors influencing research use in nursing. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 2(4), 172-183.

Grimshaw, J., Eccles, M., Thomas, R., MacLennan, G., Ramsey, C., Fraser, C., & Vale, L. (2006). Toward evidence-based quality improvement: Evidence (and its limitations) of the effectiveness of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies (1966-1998). Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21, S14-S20.

Guild, T. (2013). Letter to the editor by Theresa Guild to “open access part I: The movement, the issues and the benefits” and “open access part II: The structure, resources and implications for nurses” [Letter to the Editor]. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing. Retrieved from nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/ANAMarketplace/ANAPeriodicals/OJIN/LetterstotheEditor/Response-by-Guild-to-Nick.html

Institute of Medicine (IOM). (2001). Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Institute of Medicine (IOM). (2008). Knowing what works in health care: A roadmap for the nation Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Israel, B. A., Eng, E., Schulz, A. J., & Parker, E. A. (2005). Methods in community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Marshall, A.P., West, S.H., & Aitken, L.M. (2010). Preferred information sources for clinical decision making: Critical care nurses' perceptions of information accessibility and usefulness. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 8(4). doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2011.00221.x

Marshall, J.G. (1992).The impact of the hospital library on clinical decision making: The Rochester study. Bulletin of the Medical Library Association, 80(2):169-78.

Marshall J.G., Sollenberger, J., Easterby-Gannett, S., Morgan, L.K., Klem, M.L., Cavanaugh, S.K.,… Hunter, S. (2013). The value of library and information services in patient care: Results of a multisite study. Journal of the Medical Library Association. 101(1):38-46. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.101.1.007. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3543128/?report=classic

Melnyk, B. M., Fineout-Overholt, E., Stillwell, S.B., & Williamson, K.M. (2009). Evidence-based practice step by step. Igniting a spirit of inquiry: An essential foundation for evidence-based practice. American Journal of Nursing, 109(11), 49-52. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000363354.53883.58

Melnyk, B. M., Fineout-Overholt, E., Stillwell, S.B., & Williamson, K.M. (2010). Evidence-based practice step by step. The seven steps of evidence-based practice. American Journal of Nursing, 110(1), 51-53. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000366056.066056.d2

Morgan, S.H. (2009). The Magnet® model as a framework for excellence. Journal of Nursing Care and Quality, 24(2), 105-108.

Profetto-McGrath, J., Smith, K.B., Hugo, K., Taylor, M., & El-Hajj, H. (2007). Clinical nurse specialists use of evidence in practice: a pilot study. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 4(2), 86-96.

Sackett, D. L., Straus, S. E., Richardson, W. S., Rosenberg, W., & Haynes, R. B. (2000). Evidence-based medicine: How to practice and teach EBM. Edinburgh, UK: Churchill Livingstone.

Solomons, N.M. & Spross, J.A. (2011). Evidence-based practice barriers and facilitators from a continuous quality improvement perspective: An integrative view. Journal of Nursing Management, 19 (1), 109-120.

Thompson, C., McCaughan, D., Cullum, N., Sheldon, T., & Raynor, P. (2005). Barriers to evidence-based practice in primary care nursing - Why viewing decision-making as context is helpful. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(4), 432-444