Shared governance is the structure through which nurses at all levels in an organization seek collaborative decision making. Recently the emergence and transition from shared governance to professional governance has become prevalent in literature. With this transition, nurses go beyond participation in their practice to ownership, accountability, and authority. The evaluation of established shared governance structures, membership, and activities using the Council Health Survey was an initial step to determine the current state of governance at a quaternary medical center within the Midwest United States. Clinical nurse shared governance site council chairs led a pre-post project that assessed the effectiveness of the current structure of shared governance and implementation of a standardized orientation for new or interested members. Results demonstrated a stable shared governance process with future opportunities to build upon strengths with transition to professional governance.

Key Words: governance, shared governance, professional, registered nurses, clinical nurses, quality improvement

...successful shared governance results in professional growth, increased nursing leadership competence, and quality improvement.Shared governance is the structure through which nurses at all levels in an organization come together for collaborative decision making (DeChairo-Marino et al., 2018). Clinical nurses’ active involvement and engagement in shared governance is essential as it directly impacts their practice (Porter-O’Grady, 2019). Shared governance supports positive nursing working environments and patient outcomes (Brennan & Wendt, 2021; Williams & Christopher, 2023). Moreover, successful shared governance results in professional growth, increased nursing leadership competence, and quality improvement (Hess et al., 2020). The organizational, nursing, and patient benefits of shared governance are supported in the literature. Nursing owning their practice at the bedside and beyond is critical for the profession.

With this transition nurses go beyond participation in their practice to ownership, accountability, and authority.Since its inception over forty years ago, shared governance has evolved. Early literature highlights the benefits of effective shared governance structures and functions including increased work empowerment, job satisfaction, and improved patient and nurse outcomes (Kutney-Lee et al., 2016; Purdy et al., 2010; Spence Laschinger, 2008). Over time shared governance structures and processes have grown, reinforced by the national recognition programs of the American Nurses Credentialing Center. Recently the emergence and transition from shared governance to professional governance has become prevalent in literature. With this transition nurses go beyond participation in their practice to ownership, accountability, and authority (Porter-O’Grady & Clavelle, 2021). Despite this advancement in terminology and functions it is important to acknowledge that foundational governance structures must be established and effectively in place.

Specifics of Site Shared Governance

A 938-bed quaternary medical center within the Midwest United States was an early adopter and worked to implement nursing shared governance in the 1980s as it initially evolved. Terminology changed over time as nursing shared governance went from a “professional nursing assembly” to “nursing professional practice councils” to “nursing alliance coordinating councils” to “nursing shared governance councils and committees” and finally to “nursing professional governance.” Historically at this site, clinical nurses consistently led the councils and developed increasing responsibility and autonomy over nursing practice.

Historically at this site, clinical nurses consistently led the councils and developed increasing responsibility and autonomy over nursing practice.As the organization became part of a healthcare system, and through subsequent expansions, nursing shared governance remained a cornerstone of the nursing culture and the way that the organization moved nursing practice forward. The site invested in a dedicated nursing shared governance budget in the 1990s and its bylaws became more detailed over time to address the needs of various councils and scope. Today, governance and nursing practice are guided by a professional practice model comprised of ten essentials that fall under either professional practice or care delivery which drives how nurses practice and deliver care.

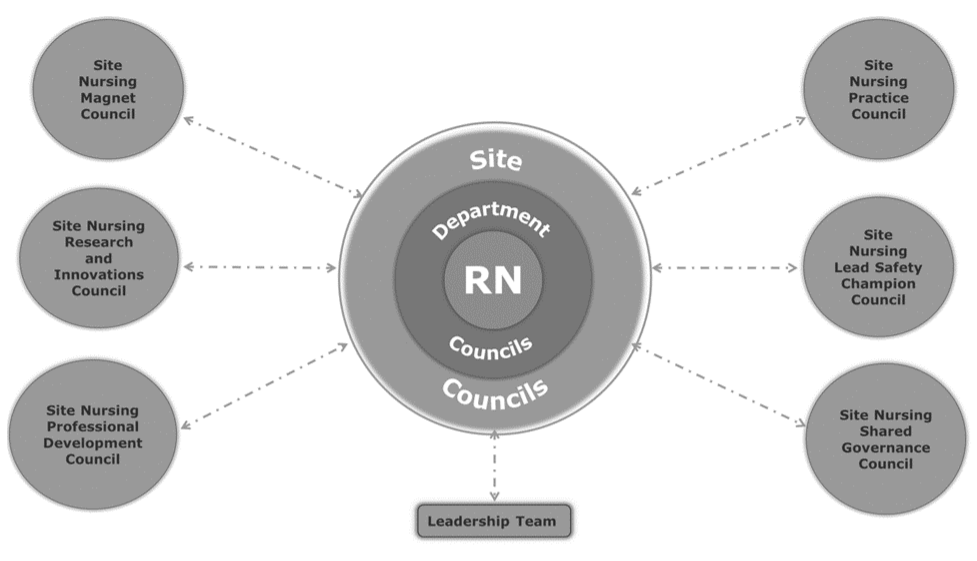

Currently the site employs over 2000 nurses and has 40 elected decisional area councils for each inpatient, outpatient, and ambulatory department. Leaders are elected by teammates (e.g., registered nurses [RNs], unlicensed personnel) from their respective departments. The flat structure of shared governance at the site is displayed in Figure 1. Each unit council has an elected chair, who is the leader of shared governance in the designated area. The unit council chair is provided monthly leadership development and partners with the elected site chair, who collaborates directly with the Vice President/Chief Nursing Officer.

Figure 1. Site Governance Structure

In addition to unit governance, there are six hospital-level councils focused on over-arching site leadership, practice, professional development, research, safety, and Magnet® (Figure 1). Each hospital level council is supported by a director of nursing leader. The hospital level councils have bidirectional participation and communication with corresponding system level councils. The site has over 350 clinical nurses engaged in a formal shared governance position. Members are asked to commit to at least a two-year term.

Project Aim

The purpose of this quality improvement project was to evaluate the effectiveness of a long-established shared governance structure at one quaternary site within a nationwide non-profit healthcare system. The secondary objective was to develop a "Shared Governance 101" (SG 101) orientation program to educate new members and assess the confidence of new clinical nurses to governance roles. A one-year follow-up of SG 101 assessed the stability of governance and changes post-implementation. The project was reviewed by the institutional review board and deemed non human subjects.

SG 101 Overview

The site shared governance chair and Magnet® council chair obtained approval for program initiation, development, and budget allocation for paid orientation from the Magnet® program director and Vice President/Chief Nursing Officer. Subsequently, the site shared governance chair and five council chairs cross-walked previously utilized electronic information materials and streamlined content to develop a one-hour SG 101 orientation.

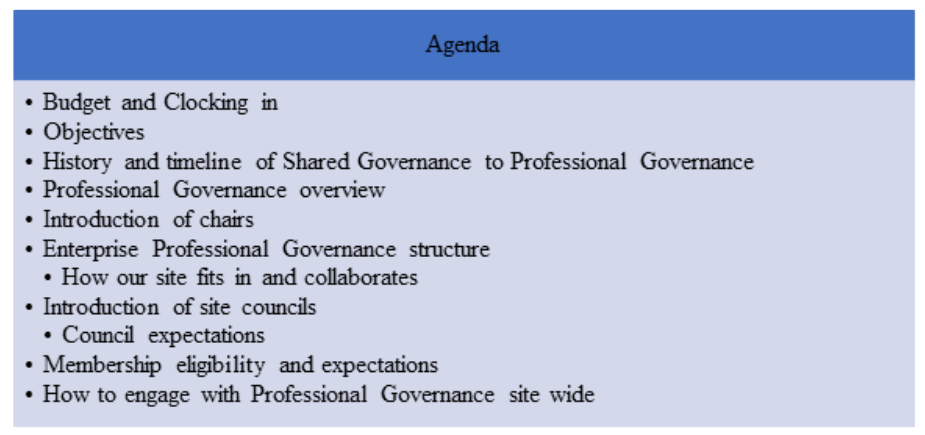

SG 101 sessions began quarterly offerings in July 2022 with virtual and in person options. This orientation was led by shared governance chairpersons and included a brief history, system and site structure and accountabilities, key concepts, purposes of councils, and introductions of chairs. The full agenda is displayed in Figure 2. Following the overview, new members met with their respective council chairperson to discuss individual council expectations and form a professional connection. If a participant was a department chair, they met with the overall SG site chair for one-on-one orientation.

Figure 2. Shared Governance 101 Agenda

The standardized SG 101 orientation sessions were optional, but highly encouraged. Session information was shared site wide through shared governance communication channels. These included flyers shared via email, online shared websites, and staff virtual communication boards. Unit leaders supported scheduling for interested staff to attend SG 101; the time was paid from the shared governance budget.

Methods

Data Collection and Outcome Measures

Permission was obtained to utilize the Council Health Survey (CHS), which was intended to evaluate shared governance council effectiveness through three subscales: membership, structures, and activities (Hess et al., 2020). The subscale of structure assesses key elements of the foundational charter/bylaws, while the activities subscale measures the processes of council work (i.e., leadership and decision-making). The membership subscale considers the preparation and support for council members (Hess et al., 2020). This 25-item survey rates items with Likert scale responses range from 1 to 5 (1 equals strongly disagree to 5 for strongly agree), with a neutral response of three. For this project, responses were treated as continuous variables to compare means between time frames. Instrument development testing reported by Hess et al. (2020) demonstrated high internal consistency with Cronbach's alpha overall of 0.95, and the following measurements for subscales: 0.92 (structure), 0.95 (activities), and 0.89 (membership).

All shared governance representatives and clinical staff were voluntarily and anonymously asked to complete a baseline CHS in January 2022 and a follow up CHS in January 2023. Both surveys were available for six weeks to allow for participation during all regularly scheduled shared governance meetings at the unit and hospital level. Surveys were distributed via a QR code and a link to an electronic survey form.

The baseline CHS results revealed the membership item “Formal education or training for new council members/leaders” had the lowest mean score (M=3.51; SD=1.03) of all items. For this reason, along with anecdotal feedback from clinical nurses, SG 101 was developed and implemented. To evaluate SG 101, a pre-post assessment was offered prior to the training and following completion of training via an electronic platform to all participants. New members’ confidence before and after attending SG 101 was evaluated on a scale of 1-5 to identify role expectations before and after the standardized orientation. Additionally, free text questions collected new knowledge obtained and program feedback.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe participant characteristics. Independent sample t-tests were utilized to compare results across the CHS individual items from January 2022 to January 2023. Both samples (2022 and 2023) were > 30, thus parametric testing, specifically independent sample t-tests, were utilized. Evidence has been shown with Likert scale data, due to the central limit theorem, the sampling mean is Gaussian indicating the ability to utilize parametric testing (DeWees et al., 2020). New shared governance members confidence related to role responsibilities before and after attending SG 101 was assessed via self-report on a Likert scale (1: no confidence to 5: extremely confident) and evaluated with a paired sample t-test. All statistical testing was completed in SPSS (Version 27) with an alpha level of .05.

Results

Demographics for participants who completed the CHS in January 2022 and January 2023 are presented for comparison (see Table 1). Overall, both groups were comparable across years of experience, time in shared governance, and professional role breakdown. Out of 350 shared governance representatives at the site, 83 participated in 2022 for a 24% response rate. In 2023 the response rate was 21% with 73 respondents out of a possible 350.

Table 1. Characteristics of Sample

|

|

2022 (n= 83) |

2023 (n=73) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Demographics |

n |

(%) |

n |

% |

|

Role |

|

|

|

|

|

Non-RN representative |

5 |

6 |

2 |

2.7 |

|

Registered Nurse |

71 |

85.5 |

59 |

80.8 |

|

Leader |

7 |

8.4 |

12 |

16.4 |

|

Years at site |

|

|

|

|

|

0-2 |

16 |

19.3 |

10 |

13.7 |

|

3-5 |

24 |

28.9 |

20 |

27.4 |

|

6-9 |

20 |

24.1 |

20 |

27.4 |

|

≥10 |

23 |

27.7 |

23 |

31.5 |

|

Years in shared governance |

|

|

|

|

|

<1 year |

23 |

27.7 |

12 |

16.4 |

|

1-2 |

21 |

25.3 |

17 |

23.3 |

|

3-4 |

22 |

26.5 |

20 |

27.4 |

|

>4 years |

17 |

20.5 |

24 |

32.9 |

Note. Non-RN representatives are certified nursing assistants and health unit coordinators. A registered nurse is a clinical nurse who works in direct patient care. Leaders are supervisors, managers, or directors.

The CHS with subscales and item means are displayed in Table 2. There was no significant difference in any of the items from January 2022 to January 2023. To evaluate the impact of SG 101, the CHS item that specifically addresses formal education or training for new council members increased from 3.51 to 3.63 although not statistically significant (p= .45). Overall, 80% (n=20) of the mean scores in both 2022 and 2023 were ≥4 indicating agreement. Many of the items' mean scores remained the same, or within .10 of initial mean score indicating stability in the sites shared governance structures, activities, and membership. In this project, reliability was examined for the total instrument and each subscale with Cronbach’s alpha. The Cronbach’s alpha for the CHS instrument was excellent (.955), and subscales of activities (.955), membership (.854), and structures (.951).

Table 2. Council Health Survey Mean Score Comparison

|

|

January 2022 |

January 2023 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Council Health Survey Subscales and Items |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

p |

|

Structures (Our council has charter/bylaws that:) |

|

|

|

|

Define its work |

4.29 (0.65) |

4.33 (0.77) |

0.73 |

|

Describe expectations of its council members |

4.30 (0.60) |

4.27 (0.80) |

0.81 |

|

Define its membership |

4.29 (0.62) |

4.30 (0.80) |

0.91 |

|

Activities (Our council members:) |

|

|

|

|

Have management leadership team engaged in council work |

4.36 (0.61) |

4.27 (0.80) |

0.45 |

|

Regularly attend meetings as specified in charter/bylaws |

4.34 (0.63) |

4.23 (0.72) |

0.33 |

|

Are engaged during meetings |

4.28 (0.69) |

4.33 (0.58) |

0.62 |

|

Make decisions that reflects values & preferences of those they represent |

4.31 (0.73) |

4.27 (0.65) |

0.73 |

|

Complete assigned council work between meetings |

4.02 (0.75) |

4.05 (0.76) |

0.80 |

|

Use effective, direct, & respectful communication |

4.45 (0.52) |

4.38 (0.60) |

0.49 |

|

Manage conflict effectively & respectfully |

4.35 (0.67) |

4.32 (0.66) |

0.75 |

|

Have necessary computer & project management skills to perform council activities |

4.18 (0.80) |

4.19 (0.76) |

0.93 |

|

Use data and/or evidence-based practice in making decisions |

4.22 (0.68) |

4.22 (0.71) |

0.99 |

|

Have council chairs & management leadership teams that collaborate on council work |

4.36 (0.53) |

4.21 (0.80) |

0.15 |

|

Use consensus to make decisions |

4.34 (0.67) |

4.34 (0.61) |

0.96 |

|

Makes meaningful decisions |

4.25 (0.70) |

4.29 (0.72) |

0.76 |

|

Use decisions to change practice |

4.22 (0.75) |

4.15 (0.72) |

0.58 |

|

Makes decisions aligned with organization's strategic goals |

4.28 (0.59) |

4.29 (0.63) |

0.91 |

|

Communicates decisions to all stakeholders |

4.18 (0.68) |

4.12 (0.73) |

0.61 |

|

Participates in activities that improve care of patients |

4.30 (0.62) |

4.32 (0.57) |

0.89 |

|

Participates in activities that improve professional practice environment |

4.25 (0.70) |

4.25 (0.62) |

0.95 |

|

Membership (Our council has:) |

|

|

|

|

Strategies to ensure members have dedicate time to complete council work |

3.95 (0.85) |

3.95 (0.94) |

0.96 |

|

Formal education or training for new council members/leaders |

3.51 (1.03) |

3.63 (1.02) |

0.45 |

|

Processes for selecting and deselecting council members |

3.99 (0.71) |

3.99 (0.89) |

0.99 |

|

Established clear avenues for non-members to contribute to council work |

3.81 (0.92) |

3.71 (0.98) |

0.53 |

|

A process to assess each other's participation in the council |

3.54 (1.05) |

3.45 (1.03) |

0.59 |

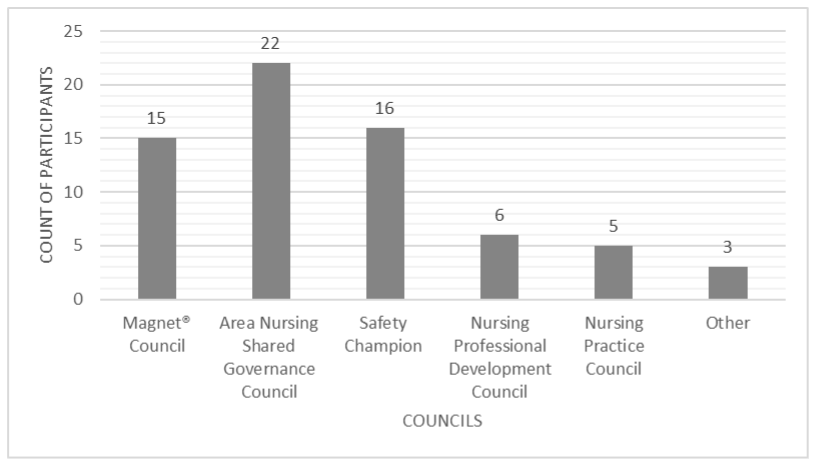

Initial survey (January 2022) means scores for the membership subscale in the neutral response category (<3.5) along with anecdotal feedback from members prompted the development and initiation of SG 101. Thus far eight SG 101 orientation sessions have occurred with (n=67) participants. Participant breakdown by shared governance council is shown in Figure 3 and evenly distributed between site and unit councils. For the participant category of other, sessions were expanded to include any interested teammate in the facility.

Figure 3. Shared Governance 101 Participant Breakdown by Council (n=67)

To evaluate the effectiveness of the SG 101 sessions paired sample t-tests were used to evaluate nurses’ self-rated confidence before and after the standardized orientation session. Data showed a mean difference from before (M=3.36; SD=1.12) to after the session (M= 4.66; SD=0.48); [t (66) = -10.47) = p<.001], indicating a significant increase in confidence for role responsibilities in shared governance. Consistent themes present in free text feedback related to new knowledge gained from SG 101 included training and information access, technological resources, navigating workflow, role responsibilities, and professional connections.

Discussion

Implementation of a SG 101 orientation session after baseline CHS results increased new members' confidence in role expectations.This quality improvement project formally assessed the long-established shared governance effectiveness at a large quaternary medical center. Results of the CHS demonstrated stability across all subscales, with the greatest opportunities in the membership items. Interestingly, scores did not significantly change in any of the items, but instead highlighted that the site maintained consistent scores in structures, membership, and activities. Implementation of a SG 101 orientation session after baseline CHS results increased new members' confidence in role expectations. Analysis of free text response feedback from the sessions suggested positive professional networking and acceptance within new roles. Moving forward, results obtained from the membership subscale can inform future opportunities. Because the majority of responses remained in the neutral category, there is an opportunity to formalize processes and evaluations.

Results of this project are similar to work that showed no significant differences in CHS scores with a standardized orientation (Williams & Christopher, 2023). The major difference was that this project was owned and implemented by clinical nurses involved in shared governance councils supported by leadership. Additionally, in this project only members of shared governance councils or clinical nurses were eligible to complete the CHS. This underscores the importance of clinical nurse voice, ownership, and accountability, which are noted as key principles of professional governance instrumental to success (Porter-O’Grady & Clavelle, 2021).

...empowering nurses with confidence in governance roles may in turn positively impact their engagement in the process and thus the clinical care environment.Additionally, this project included an assessment of the confidence of new members to show the return on investment for paid attendance at SG 101. Results of pre and post confidence highlighted that, when clinical nurses are given the tools and resources, they gain confidence in shared governance leadership responsibilities. Notably, nurses' confidence and participation in shared governance may lead to greater engagement. This is important as greater engagement has been linked with improved patient outcomes and quality of care (Kutney-Lee et al., 2016). Hence empowering nurses with confidence in governance roles may in turn positively impact their engagement in the process and thus the clinical care environment (Jaber et al., 2022).

As literature has described, healthcare organizations are shifting toward professional governance; it is important to note similar characteristics. Professional governance must have strong engagement from both the bedside clinicians as well as leaders within the organization (Wilson & Galuska, 2020). Yet an important distinction must be made that ownership of the work truly needs to be in the hands of clinical nurses, while leaders fill support, mentor, and guidance roles. The breakdown of decisional authority can be documented in accountability grids and carry over to councils and position descriptions (Wisner et al., 2024). At the project site accountability is encompassed in the charters, bylaws, and membership expectations that are reviewed as part of SG 101, and this reflected as a strength in CHS activities in both pre-and post-scores. Attributes of professional governance have been defined as accountability, professional obligation, collateral relationships, and decision-making with a professional governance scale published after the initiation of this project (Weston et al., 2022). The results of this project showed that a formal evaluation can aid in understanding the perceptions of clinical nurses about the current state of the structure and determining building blocks for future opportunities.

...ownership of the work truly needs to be in the hands of clinical nurses, while leaders fill support, mentor, and guidance roles.Nurses within governance need to encompass both shared decision making and professionalism, no matter the term utilized in the organization (Hess, 2017). As nurses assess the effectiveness of governance structures, there will be a greater understanding of their role in healthcare organizations (i.e., systems), the impact on clinical practice, and professional contributions. This assessment needs to include a greater focus on evidence-based and interprofessional practice with an emphasis on value and outcomes (Porter-O’Grady et al., 2022). The ownership of the clinical nurses in the context of this project and subsequent work exemplifies professional governance in practice in real world settings.

Nurses within governance need to encompass both shared decision making and professionalism, no matter the term utilized in the organization.The site and system in this project transitioned to the more current terminology and additional components of professional governance in January 2024. This transition focuses on nurse control over practice, competence, quality, and new knowledge (Porter-O’Grady & Clavelle, 2021). This project has demonstrated that the site has effective structures as evidenced by CHS results. However, there is still a need to shift to more ownership of decision-making versus consulting on practice changes. Additional key transition tactics include expectations, demonstration, value, sustainability, and interprofessional relationships for all nurses. With this transition there are opportunities to build upon CHS results by incorporating additional components of professional governance. Plans for the way ahead have been disseminated by clinical nurse professional governance site and system chairs.

Implications

Results highlighted the stability of shared governance, while simultaneously challenging the site chairs to improve...The formal evaluation of effectiveness of shared governance at the site aided governance chairs in identifying opportunities for improvement. Additionally, the repeated evaluation provided all clinical staff at the site with a voice to share their perspectives. Results highlighted the stability of shared governance, while simultaneously challenging the site chairs to improve and move toward professional governance. The SG 101 session has been provided to over 50 new members; individuals across the site can utilize this forum to learn about shared governance at the site and avenues of involvement in their areas of interest.

The standardized SG 101 orientation session and evaluation has increased new member knowledge and confidence in role expectations, greater engagement, and networking. The standardized orientation will continue to be offered quarterly with ongoing evaluation for improvement. This standardized orientation approach could be incorporated within any governance structure, with orientation materials specific to individual sites and structures. For new employees, leaders, and site shared governance representatives, this session provides foundational knowledge about organizational culture and the role that governance has at the site.

Limitations

This quality improvement initiative and subsequent program development were specific to the site and corresponding governance participants. The CHS may have been completed by individuals in both 2022 and 2023, since it was conducted anonymously and terms in shared governance at the site vary between 2-4 years. In attempts to mitigate this, January was strategically selected due to the turnover of elected representatives on the council. Although the response rate is typical for surveys, responses may be biased towards those involved in governance and may not represent all nurses at the site. Lastly, scores in the neutral categories for the subscale of membership may have been impacted by the Omicron surge of COVID in January 2022 and subsequent effects on staffing and governance participation.

Conclusions

Governance is an essential component of shared decision making, ownership, and engagement for clinical nurses.Governance is an essential component of shared decision making, ownership, and engagement for clinical nurses. This project highlighted the need for the application of shared and professional governance assessments in healthcare sites and systems. A formal evaluation of shared governance effectiveness can provide site chairs, executive leadership, and participating members valuable data on the current status and opportunities for development. Secondly, clinical nurses are integral members and voices in professional governance and thus need to be active proponents and owners of decision making, especially those linked to the profession of nursing. Despite the constant change in membership and participation, the strength of this site's shared governance structure, membership and activities is reflected in our results. Empowering new governance members through an orientation can increase confidence for roles which can concurrently benefit the organization, governance, and the nursing profession. Further work to assess the impact of governance on healthcare outcomes linked to professional components is needed.

Authors

Jeanne Hlebichuk, PhD, RN, NE-BC

Email: Jeanne.hlebichuk@aah.org

ORCID ID: 0000-0001-8332-7188

Jeanne Hlebichuk is a nurse scientist at Aurora St. Luke’s Medical Center in Milwaukee, WI. She obtained a bachelor’s degree in nursing and Doctor of Philosophy from Marquette University and a master’s in nursing executive leadership from University of San Diego. She has worked in a variety of acute and outpatient clinical settings as a clinical nurse, leader, and researcher.

Deanna Shaver, BSN, RN, MEDSURG-BC

Email: deanna.shaver@aah.org

Deanna Shaver BSN, RN, MEDSURG-BC has worked in the neurosurgical units for the last 12 years since graduating with a bachelor’s degree from Columbia College of Nursing in 2011. She has been involved with nursing professional governance for the last ten years and was elected and served as site nursing professional governance council chair for the last four years.

Olivia Due, BSN, RN, CV-BC

Email: olivia.due@aah.org

Olivia Due is a clinical nurse in the Cardiovascular Intensive Care Unit and has worked as a clinical nurse for over 8 years. She served as the Magnet® Council Chairperson for 4 years and continues to be involved in professional governance.

Sara Marzinski, DNP, RN, AGCNS-BC

Email: sara.marzinski@aah.org

ORCID ID: 0000-0002-4942-642X

Sara Marzinski is the Director of the Magnet® Program at Aurora St. Luke’s Medical Center. She serves as a leadership resource and mentor for nursing shared governance. She has participated as a clinical nurse or leadership support within nursing shared governance for over 20 years.

Disclosure: The authors have no conflicts to declare.

References

Brennan, D., & Wendt, L. (2021). Increasing quality and patient outcomes with staff engagement and shared governance. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 26(2). https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol26No02PPT23

DeChairo-Marino, A. E., Collins Raggi, M. E., Mendelson, S. G., Highfield, M. E. F., & Hess, R. G. (2018). Enhancing and advancing shared governance through a targeted decision-making redesign. Journal of Nursing Administration, 48(9), 445-451. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000000647

DeWees, T. A., Mazza, G. L., Golafshar, M. A., & Dueck, A. C. (2020). Investigation into the effects of using normal distribution theory methodology for Likert scale patient-reported outcome data from varying underlying distributions including floor/ceiling effects. Value in Health, 23(5), 625-631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2020.01.007

Hess, R. G. (2017). Professional governance: Another new concept? Journal of Nursing Administration, 47(1), 1-2. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000000427

Hess, R. G., Jr., Bonamer, J. I., Swihart, D., & Brull, S. (2020). Measuring council health to transform shared governance processes and practice. Journal of Nursing Administration, 50(2), 104-108. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000000849

Jaber, A., Ta’an, W. F., Aldalaykeh, M. K., Al-Shannaq, Y. M., Oweidat, I. A., & Mukattash, T. L. (2022). The perception of shared governance and engagement in decision-making among nurses. Nursing Forum, 57(6), 1169-1175. https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12817

Kutney-Lee, A., Germack, H., Hatfield, L., et al. (2016). Nurse engagement in shared governance and patient and nurse outcomes. Journal of Nursing Administration, 46(11), 605-612. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000000412

Porter-O’Grady, T. P. (2019). Principles for sustaining shared/professional governance in nursing. Nursing Management, 50(1), 36-41. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NUMA.0000550448.17375.28

Porter-O’Grady, T. P., & Clavelle, J. T. (2021). Transforming shared governance: Toward professional governance for nursing. Journal of Nursing Administration, 51(4), 206-211. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000000999

Porter-O’Grady, T., Weston, M. J., Clavelle, J. T., & Meek, P. (2022). The value of nursing professional governance: Researching the professional practice environment. Journal of Nursing Administration, 52(5), 249-250. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000001141

Purdy, N., Spence Laschinger, H. K., Finegan, J., Kerr, M., & Olivera, F. (2010). Effects of work environments on nurse and patient outcomes. Journal of Nursing Management, 18(8), 901-913. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01172.x

Spence Laschinger, H. K. (2008). Effect of empowerment on professional practice environments, work satisfaction, and patient care quality: Further testing the Nursing Worklife Model. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 23(4), 322-330. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NCQ.0000318028.67910.6b

Weston, M. J., Meek, P., Verran, J. A., et al. (2022). The Verran professional governance scale: Confirmatory and exploratory analysis. Journal of Nursing Administration, 52(5), 273-279. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000001147

Wilson, R., & Galuska, L. (2020). Professional governance implementation. Nurse Leader, 18(5), 467-470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mnl.2020.04.011

Williams, M., & Christopher, R. (2023). Moving shared governance to the next level: Assessing council health and training council chairs. Journal of Nursing Administration, 53(1), 6-11. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000001235

Wisner, K., Collins, A., & Porter-O’Grady, T. (2024). A road map for the development of a decisional authority framework for professional governance using accountability grids. Journal of Nursing Administration, 54(2), 79-85. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000001386