In Spring 2020, some nurses in the United States experienced financial hardship associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Nurses House, Inc. responded and provided $2,734,500 in emergency grants to the 2,484 nurses who applied and met the eligibility criteria. The question arose, How long did this experience continue to impact the financial well-being of these nurses? Studies have been reported about the long-term physical, psychological, social, and workforce impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on nurses, but little was found about its long-term financial impact. An electronic survey was conducted to explore the endurance of the COVID-19 related financial hardship the grant recipient nurses had experienced and to determine if the financial crisis was more enduring for some nurses than others. The survey consisted of five categories of variables presented in 38 statements, along with 9 items eliciting demographic information. Specific categories measured included Current Personal Physical Health, Personal Emotional Health, Family Health and Well Being, Economic Well Being, and Support Systems. Aggregated data about demographic characteristics, along with statistically significant correlations and factor analyses, offered information about which nurses may be more vulnerable in times of financial crisis. The survey findings can inform proactive planning and advocacy for a safety net for nurses whose financial well-being may be threatened in times of an unanticipated crisis, such as a pandemic.

Key Words: COVID-19 related financial crisis, nurses, long-term financial impact

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly impacted many, including nurses, some of whom faced financial challenges. In 2023, the American Nurses Foundation (ANF) published its annual assessment about the state of the nurse workforce. The authors noted that, among other issues, financial well-being has worsened from the year before, stating that "sixty-one percent of the nurses surveyed described managing their financial hardship by using savings or emergency funds (28%), delaying major purchases (27%), and relying more on credit cards (19%)” (ANF, 2023, p. 6). ANF surveyors found that student loan debt was especially concerning to newer nurses. The ANF report supports the need to examine how financial distress experienced by nurses in association with COVID-19 has evolved.

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly impacted many, including nurses, some of whom faced financial challenges.

Background

In March 2020, Nurses House, Inc., a national organization that provides temporary financial assistance to nurses who are ill or injured, launched a COVID-19 Emergency Grant. The COVID-19 Emergency Grant was a unique offering specifically in response to nurses who were financially impacted by the unprecedented pandemic. With funding predominantly from the ANF, as well as other entities, Nurses House, Inc., provided a total of $2,734,500 over a three-month period to 2,484 nurses across the United States (U.S.) who reported experiencing financial distress from being out of work due to factors associated with the COVID-19 pandemic (ANF, 2023; Millenbach et al., 2021). Nurses House, Inc. continues to receive grant funding requests from nurses who suffer from the long-term health and financial impacts of COVID-19.

Nurses House, Inc. continues to receive grant funding requests from nurses who suffer from the long-term health and financial impacts of COVID-19.

Millenbach et al.'s (2021) original study described the demographics of the grant recipients and the nature of their financial hardship. The study findings determined that there is no comprehensive financial safety net for nurses. The authors published several follow-up articles based on this study (Brennan, 2023, Millenbach 2023, and Pettis, 2021). Brennan et al (2023) proposed advocacy and policy reform at the federal, state, and local governmental levels regarding the need for extended financial and healthcare provisions for nurses in times of crisis. A blog, entitled “Who cares for the Nurses who Care for you,” was published by Pettis et.al. (2021). Finally, Millenbach et.al. (2023) found in their qualitative study of these nurses the expression of gratitude for the financial support provided by Nurses House, Inc., but also reinforced the need for a financial safety net to ensure social justice for nurses in the time of a disaster like COVID-19.

Study Aim

This study was undertaken to follow up on the original emergency grant recipients' study (Millenbach et al., 2021). We sought to identify factors that may contribute to the continued or resolved financial vulnerability of these nurses. This information will enable proactive planning and advocacy to prevent, or at least mitigate, the experience of nurses vulnerable to a long-term financial emergency in times of an unanticipated crisis.

This study was undertaken to follow up on the original emergency grant recipients' study

Methods

Subjects

Our subjects were the 2,484 nurses who had received a COVID emergency grant in 2020. Information was requested from these nurses to query their current financial stability. The prior study described nurses who received an emergency grant in 2020 from Nurses House, Inc., and factors associated with experiencing a financial crisis related to COVID-19 (Millenbach et. al., 2021).

Instrument Development

From the results of the previous Millenbach et.al. (2021) mixed-method study, five constructs, or categories, emerged to provide a blueprint for the current survey. The nurses’ statements were represented in 38 items distributed into the category they were deemed to represent, as follows:

- Construct 1 was Current Personal Physical Health, encompassing 7 items. One example item was “I have had a repeated COVID episode at least ”

- Construct 2, Personal Emotional Health, consisted of 5 An example of an item in this category is “I routinely take actions to maintain my personal well-being.”

- Construct 3, Family Health and Well Being, was comprised of 5 items. “I have direct responsibility for caring for family member/s” is an example of this category’s items.

- Construct 4, Economic Well Being, was the main interest of this study, and included 14 “I live paycheck to paycheck” is an example of this fourth category.

- Construct 5, Support Systems, included 7 “I have a strong support system from my family” is an example of an item in the fifth category.

Respondents were requested to indicate the extent of their agreement with each statement by indicating their response on a Likert scale of 0 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A non- applicable (N/A) option was available.

Nine items elicited demographic characteristics with the response option to check the one that applied or to fill in a discrete number. Included were age, gender, ethnic group affiliation, number of persons in household, household composition, number of household members employed, annual salary before COVID, current annual salary, and current employment status. Content validity of the instrument was established by an expert nurse reviewer panel prior to its distribution. IRB approval was granted by Niagara University's Institutional Review Board.

Data Analysis Plan

Survey responses were summarized using descriptive statistics, and Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to assess the internal consistency of each multi-item scale. A Financial Instability subscale was created from five items within the Economic Well-Being category. Demographic characteristics were analyzed using frequency and percentage distributions. Visualizations were used to display response patterns. Point-biserial correlations examined relationships between demographic variables and financial instability, followed by causal inference analysis using the DirectLiNGAM algorithm. Two multiple regression models were conducted, one using composite scale scores and the other using individual items, with analyses performed using Minitab® (2021) and stepwise selection (α = 0.15). Multiple regression analyses were conducted to further investigate the factors that contributed to enduring financial distress among nurses who received a COVID-19 emergency grant from Nurses' House Inc.

Survey Distribution

The 2,484 nurses who had received a Nurses House, Inc. emergency grant in 2020 were sent an invitation to participate in this follow-up study electronically via e-mail, with a cover letter describing the study, a statement regarding consent to their participation, and a link to the follow-up survey, which used CVENT 4.0 (2020). CVENT (2020) is a conference app used for scheduling and obtaining feedback, with a specific module for conducting surveys. This product allows for confidential or anonymous surveying, uploads an email list, and downloads replies into a spreadsheet file. Of the 2,484 nurses surveyed, however, 120 were returned as "undeliverable," reducing the potential sample size to 2,364. The survey was conducted between November 20, 2023 and December 30, 2023. Thank you and/or reminders were sent 2 weeks and 1 week before the survey closed in an effort to maximize the response rate.

Results

A total of 353 responses were received for the survey, representing a 14.9% response rate from 2,364 eligible participants. While a greater response rate was desired, according to “Survey Anyplace, (Lindemann, 2024), the average response rate achieved with an app survey is 13%. Review of the partial responses suggested that some participants left varying numbers of questions unanswered, but did not abandon the survey altogether. Some incomplete surveys contained useful information, so these responses were included to provide valuable insights.

Demographics

The demographic information was aggregated, and the data are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Respondent Demographic Information (n=353)

|

Demographic Item |

Response Option |

Number (n) |

Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Age (n=276; 78.19% responded) |

41-50 51-60 31-40 ≥61 20-30 |

104 71 68 23 10 |

29.46 20.11 19.26 6.52 2.83 |

|

Race (n=593; 100% responded) |

Black Prefer not to indicate White Asian Other |

99 89 79 68 18 |

28.05 25.21 22.38 19.26 5.1 |

|

Gender (n=276; 78.19% responded) |

Female Male Prefer not to indicate |

248 25 3 |

70.25 7.08 .85 |

|

Nursing License (n= 259; 73.37% responded) |

RN LPN/LVN |

209 50 |

59.21 14.16 |

|

Household Size (n=268; 75.92% responded) |

≥4 3 2 1 0 |

142 57 44 23 2 |

40.23 16.15 12.46 6.52 0.57 |

|

#Household Member(s) Employed (n=268; 75.92% responded) |

2 1 3 0 ≥4 |

113 102 30 13 10 |

32.01 28.9 8.5 3.68 2.8 |

The majority of nurse-grantees who replied to the survey were registered nurses ([RNs]; 59.21%), primarily aged between 41–50 years (29.46%). Ethnic affiliation was mostly African American (28.05%) or White (22.38%), though approximately one quarter (25.21%) preferred not to indicate their race. Regarding gender, of those who responded, 70.25% were female, 7.08% were male, 21.81% did not respond, and 0.85% chose not to disclose their gender.

The majority of nurse-grantees who replied to the survey were registered nurses...

A total of 268 nurses provided responses regarding the number of people in their households and the number of employed individuals. Household sizes ranged from 1 to 12 members, with a median of 4 members, and households with 4 or more members accounted for 40.23% of participants. The number of employed individuals per household ranged from 0 to 5, with both the median and mode being 2 employed members per household.

The annual household median salary pre-COVID-19 was reported as $80,000 (range $25,000 to $285,000), and post-COVID-19 was $89,000 (range $18,000 to $240,000). Household salaries from before to after COVID increased for 60.4% of the respondents, remained the same for 9.1%, and decreased for 30.5%. The annual individual median salary pre-COVID-19 was $80,000 (range of zero to $285,000), while the post-COVID-19 median was $84,000 (range zero to $240,000). Individual annual salaries pre to post COVID-19 increased for 58%, remained the same for 9.9%, and decreased for 32.5%, which included zero salary for 5 of the responding nurses who had been salaried pre-COVID-19.

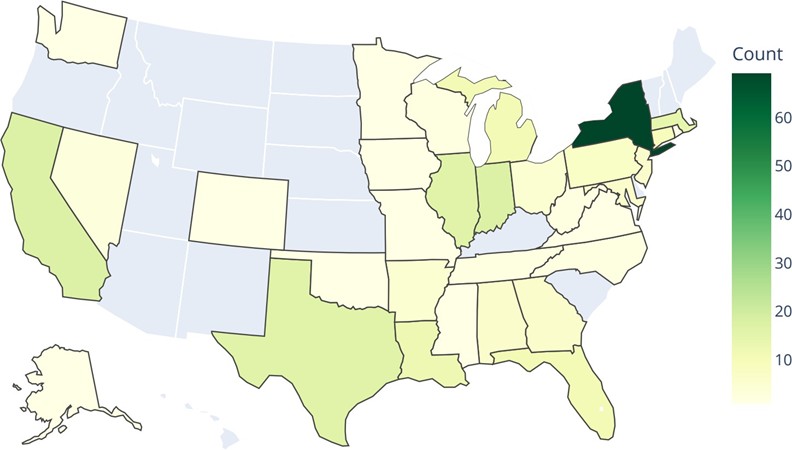

The survey also asked nurses to indicate the state where they were employed. When multiple states were mentioned, only the first state listed was considered. A total of 256 responses were received for this item. Figure 1 shows the distribution of employment states among the nurses who participated in the survey. Most respondents were employed in New York (NY) State, followed by California and Indiana. Regionally, 106 respondents (41%) worked in Northeastern states, 73 (29%) in Southern states, 54 (12%) in Midwestern states, and the remaining 23 (9%) in Western states.

Figure 1. Geographical Distribution of Employment Locale of Respondents by U.S. State

Survey Findings

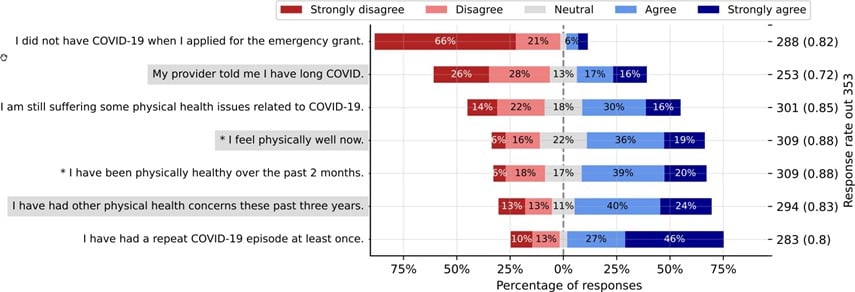

Personal Physical Health. The survey results related to the first financial distress category of Current Personal Physical Health (Figure 2) indicated that many nurses reported having contracted COVID-19 when they applied for the Nurses' House emergency grant, with some experiencing multiple infections and ongoing COVID-related health issues. However, most reported feeling well over the past two months. This category demonstrated strong reliability, with a Cronbach's Alpha of 0.808 (99% CI: 0.754–0.853), indicating high internal consistency.

Figure 2. Personal Physical Health (7 items)

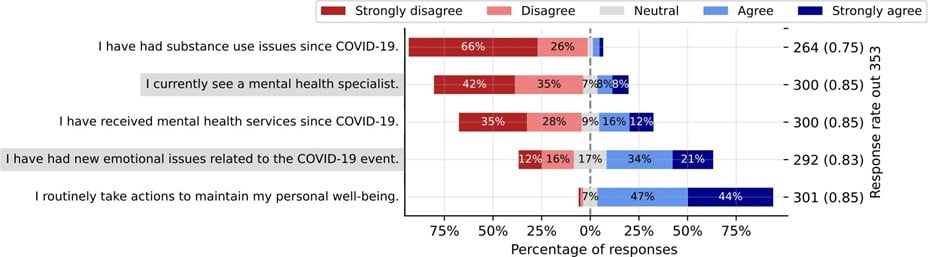

Personal Emotional Health. In the Personal Emotional Health category (Figure 3), nearly all nurses indicated that they were engaging in self-care. About half reported facing mental health challenges, although few were receiving treatment. Substance use was not reported as a significant issue. This category also showed solid reliability, with a Cronbach's Alpha of 0.797 (99% CI: 0.739–0.844), reflecting strong internal consistency.

Figure 3. Personal Emotional Health

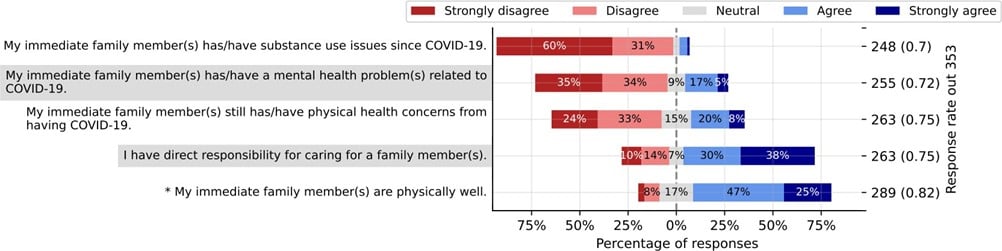

Family Health. In the Family Health category (Figure 4), many nurses reported responsibility to care for family members. The respondents indicated that their families were generally healthy, though some noted that family members had physical and/or mental health concerns. Substance use concerns were rarely mentioned. The Family Health scale demonstrated moderate reliability, with a Cronbach's Alpha of 0.640 (99% CI: 0.533–0.727), indicating acceptable internal consistency. However, it falls below the generally recommended threshold of 0.7 for adequate reliability for use as a scale (Bland & Altman, 1997; Tavakol & Dennick, 2011).

Figure 4. Family Health

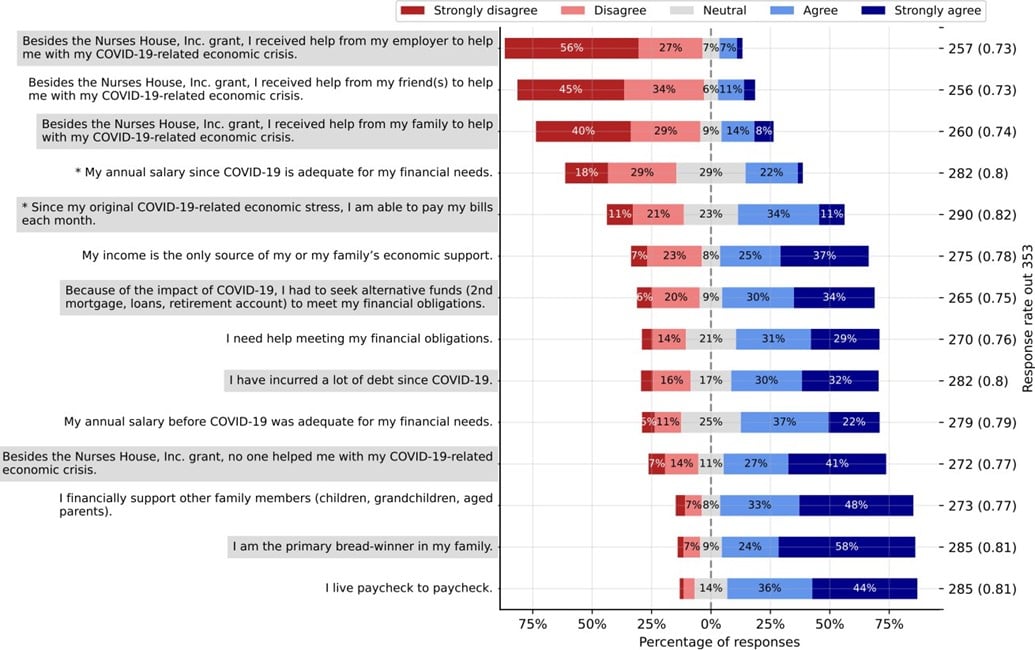

Economic Well-Being. In the Economic Well-Being category (Figure 5), the primary focus of this study, most respondents identified themselves as the primary or sole wage earners for their family, often referring to themselves as the "breadwinners" and living “paycheck to paycheck.” Many reported receiving no financial support other than the Nurses House, Inc. grant, while some received help from family members, fewer from friends, and rarely from employers. The Economic Well-Being scale exhibited strong reliability and internal consistency, with Cronbach's Alpha of 0.750 (99% CI: 0.675–0.811), indicating a high degree of internal consistency.

Figure 5. Economic Well-Being

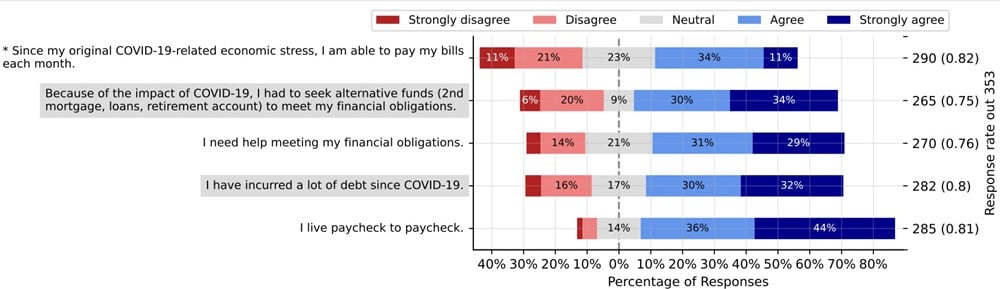

Financial Instability. The subgroup of five items selected from the Economic Well-Being category formed a Financial Instability sub-scale (Figure 6). This subgroup concentrated on the nurses' ability to manage their financial obligations, considering the economic effects of COVID-19. Many respondents indicated that they were living paycheck to paycheck, with a significant portion expressing difficulty in meeting financial obligations and reporting increased debt since the pandemic began. Some nurses were compelled to seek alternative funding sources, such as loans or retirement accounts, to remain financially afloat. The Financial Instability scale exhibited excellent reliability, with a Cronbach's Alpha of 0.846 (99% CI: 0.802–0.882), demonstrating high internal consistency among the items. The Financial Instability Sub-Scale was utilized to explore correlations with other categories.

Figure 6. Financial Instability

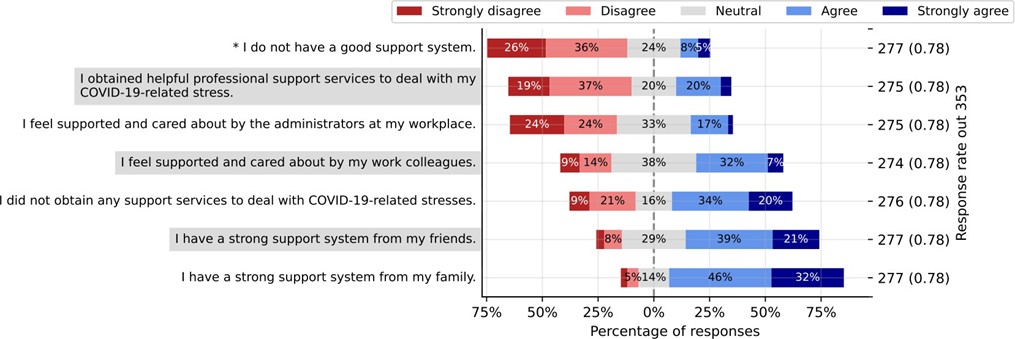

Support Systems. Perceptions of support were explored in the fifth and final category, Support Systems (Figure 7). Many respondents reported having a strong support system, with most of this support coming from family and some from friends. A few nurses felt cared for by their colleagues, but fewer felt supported by workplace administrators. Most respondents indicated that they did not receive professional support to cope with COVID-related stress. The Support Systems scale had a Cronbach's Alpha of 0.745 (99% CI: 0.676–0.803), indicating strong reliability.

Figure 7. Support Systems

Correlation and Causal Inference Analysis

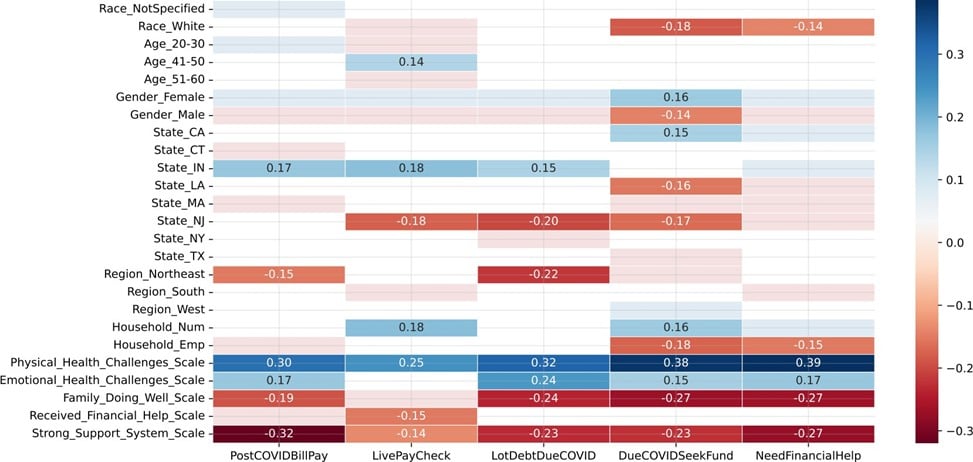

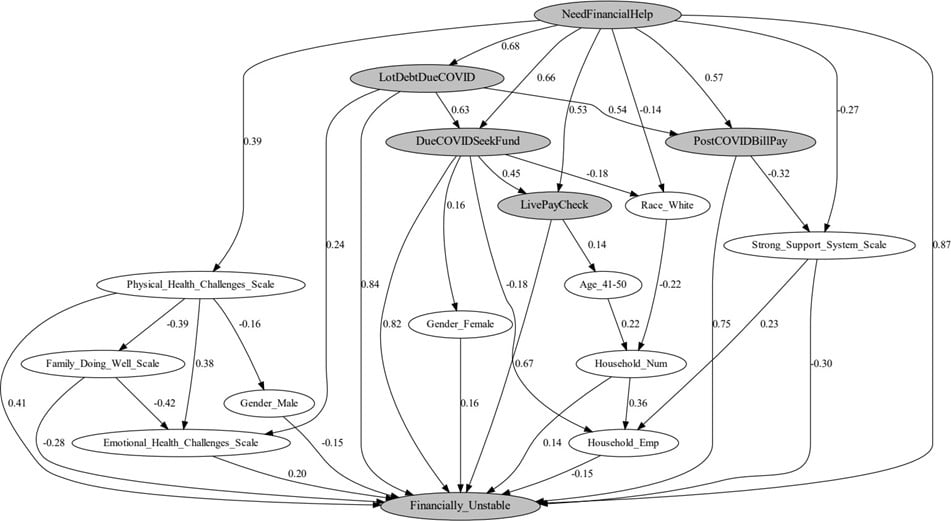

Point-biserial correlations between demographic information and financial instability were computed and are displayed in Figure 8. These correlations were further analyzed using causal inference, as shown in Figure 8, which was created with the DirectLiNGAM algorithm (Kurotani et al., 2024).

Figure 8. Correlation Analysis

Items on the x-axis in Figure 8 are directly related to the items of the financial instability subscale shown in Figure 6. PostCOVIDBillPay is an individual's inability to pay bills following COVID-19-related financial stress. LivePayCheck highlights where individuals live paycheck to paycheck, relying on each paycheck to cover basic expenses without any savings buffer. LotDebtDueCOVID describes the accumulation of significant debt as a result of the financial impact of COVID-19. DueCOVIDSeekFund refers to the need to seek alternative sources of funding, such as loans, retirement accounts, or mortgages, to meet financial obligations due to the financial strain caused by the pandemic. NeedFinancialHelp indicates the necessity for financial assistance to manage financial obligations. The y-axis lists the demographic information that correlated statistically with the items related to financial instability. The strength of the correlation appears in the bar for the statistically significant findings.

Figure 9. Causal Inference Analysis

The Financially Unstable node in Figure 9 was derived by summing the 5 factors of financial instability illustrated on the x-axis of Figure 8. Causal inference goes beyond simple correlations by suggesting potential cause-and-effect relationships between variables. In a causal diagram-like Figure 9, the directed edges (arrows) represent the direction of influence between variables. However, the arrows may be reversed depending on the context of the analysis. The strength of each relationship is represented by the coefficient next to the arrow, with positive values indicating a direct positive influence and negative values reflecting a mitigating effect.

Causal inference diagrams, such as the one presented here, can help reveal the broader pathways through which demographic factors influenced participants' financial distress, offering insights beyond the correlations observed in Figure 8. However, it is important to note that while causal analysis provides valuable insights into potential causal pathways, content experts must validate these relationships and align with existing theories before drawing definitive conclusions (Pearl, 2016).

Regression Analysis

The multiple regression analyses, presented in Tables 2 and 3, provided deeper insights into financial instability, in addition to the initial survey item analysis, correlation, and causal inference results. As shown in Figure 9, financial instability was calculated by summing the scores from the financial instability sub-scale. The sub-scale was coded with responses of "strongly agree" as +2, "agree" as +1, "disagree" as -1, and "strongly disagree" as -2. Neutral responses were coded as 0, and instances with missing data were excluded, resulting in a final dataset of 169 respondents. Both models were run using Minitab® 21.4.3, with the stepwise selection method applied at an alpha level of 0.15 to identify the most significant predictors of financial instability. Variables not meeting the selection criteria are not included in these tables.

The first model, displayed in Table 2, explored the relationship between financial instability and broader category scale responses (e.g., physical and emotional health challenges), while controlling for race, age, and gender. The results indicated statistically significant effects for physical health challenges and strong support systems, with a moderate R² value of 26.66%, suggesting the model explained a portion of the variability in financial instability The Physical Health Challenges Scale had a positive coefficient of 0.340 (p < 0.001), indicating a higher likelihood of financial instability for those with physical health issues. Figure 8 further emphasizes this, with correlations between the Physical Health Challenges Scale and indicators like PostCOVIDBillPay (r = 0.30, p < 0.05) and the Need for Financial Help (r =0.39, p < 0.05). The causal inference model in Figure 8 confirms that physical health challenges correlate with and contribute to financial instability. Table 3 reinforces this by showing that nurses still suffering from COVID-19-related health issues had a coefficient of 1.246 (p < 0.001), suggesting that ongoing health problems strongly predict continuing financial distress.

Table 2. Regression Summary for Survey Scales Associated with Financial Instability

|

Term |

Coef |

SE Coef |

T-Value |

P-Value |

VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Constant |

4.381 |

0.436 |

10.040 |

0.000 |

|

|

Physical Health Challenges Scale*** |

0.340 |

0.058 |

5.890 |

0.000 |

1.040 |

|

Strong Support System Scale*** |

-0.332 |

0.088 |

-3.750 |

0.000 |

1.050 |

|

Race White** |

-1.938 |

0.667 |

-2.910 |

0.004 |

1.030 |

Note. The causal inference model...confirms that physical health challenges correlate with and contribute to financial instability.The regression model, run using Minitab 21.2.3, was statistically significant. The stepwise reduction at alpha = 0.15 was applied to determine the best variables for the model. Demographic binary variables including age, gender, U.S. state of work, and race were controlled for during model selection, but only the Race-White variable was retained in the final model based on stepwise criteria. Each scale variable was derived by summing the corresponding items within that scale. The model was statistically significant. R-squared = 26.66%; Adjusted R-squared = 25.33%. Significance codes: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

The second regression model shown in Table 3 involved analyzing individual survey items rather than broader scales. In this model, the responses were recoded into binary values, with "agree" and "strongly agree" coded as 1, and "disagree" and "strongly disagree" coded as 0. Missing responses were again excluded, leaving the same 169 respondents. This model highlighted significant individual factors contributing to financial instability, such as race (identifying as Black -p < 0.01), physical health issues before and after COVID-19 (p < 0.001), adequacy of income, including being the sole provider of family income (p <0.001), professional support services (p < 0.01), and help received beyond the Nurses' House Inc. grant (p >0.01). This model showed a higher R² of 64.74%, indicating it explained a larger portion of the variance in financial instability.

Table 3. Regression Summary for Individual Survey Items Associated with Financial Instability

|

Term |

Coef |

SE Coef |

T-Value |

P-Value |

VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Constant |

-0.213 |

0.850 |

-0.250 |

0.802 |

|

|

Race Black** |

1.584 |

0.505 |

3.140 |

0.002 |

1.190 |

|

I am still suffering some physical health issues related to COVID-19.*** |

1.246 |

0.234 |

5.310 |

0.000 |

2.040 |

|

My income is the only source of my or my family's economic support.*** |

0.775 |

0.200 |

3.880 |

0.000 |

1.510 |

|

The number of people employed in my household |

0.547 |

0.347 |

1.580 |

0.117 |

1.460 |

|

Besides the Nurses House, Inc. grant, I received help from my family to help with my COVID-19-related economic crisis.* |

0.510 |

0.199 |

2.560 |

0.011 |

1.370 |

|

My annual salary before COVID-19 was adequate for my financial needs.* |

0.452 |

0.208 |

2.170 |

0.031 |

1.130 |

|

I obtained helpful professional support services to deal with my COVID-19-related stress. |

0.430 |

0.217 |

1.980 |

0.050 |

1.110 |

|

My immediate family member(s) still has/have physical health concerns from having COVID-19.* |

0.415 |

0.205 |

2.020 |

0.045 |

1.420 |

|

My immediate family member(s) has/have a mental health problem(s) related to COVID-19. |

0.398 |

0.217 |

1.840 |

0.068 |

1.520 |

|

I have had other physical health concerns these past three years. |

0.323 |

0.199 |

1.630 |

0.106 |

1.310 |

|

I feel supported and cared about by my work colleagues.* |

-0.554 |

0.245 |

-2.260 |

0.025 |

1.170 |

|

Besides the Nurses House, Inc. grant, I received help from my employer to help me with my COVID-19-related economic crisis.** |

-0.880 |

0.265 |

-3.320 |

0.001 |

1.380 |

|

State NY |

-1.014 |

0.564 |

-1.800 |

0.074 |

1.110 |

|

My provider told me I have long COVID.*** |

-1.118 |

0.214 |

-5.220 |

0.000 |

1.880 |

|

State LA |

-1.770 |

1.050 |

-1.690 |

0.094 |

1.080 |

|

My annual salary since COVID-19 is adequate for my financial needs.*** |

-1.927 |

0.229 |

-8.400 |

0.000 |

1.210 |

|

Age 20-30 |

-2.290 |

1.200 |

-1.910 |

0.058 |

1.120 |

Note. The regression model, run using Minitab 21.2.3, was statistically significant. The stepwise reduction at alpha = 0.15 was applied to determine the best variables for the model. Demographic binary variables including age, gender, U.S. state of work, and race were controlled for during model selection, but only the Race-Black, Age 20–30, State-NY, and State-LA variables were retained in the final model based on stepwise criteria. All other variables were coded as "strongly agree" = +2, "agree" = +1, "neutral" = 0, "disagree" = –1, and "strongly disagree" = –2. The number of people employed in the household was treated separately as a count variable starting from 0. The model was statistically significant. R-squared = 64.74%; Adjusted R-squared = 60.67%. Significance codes: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.00

Discussion

Most nurses in the United States identify as women (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2023; Hyman, 2024). , which was reflected in our study, where 90% of those who indicated their gender identified as female. Like many other female-dominated professions, nurses experienced significant financial challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. The relatively lower salaries for women compared to men (Hemez et al., 2024; Hyman, 2024) combined with additional caregiving responsibilities for children and family members further exacerbated the financial burdens for nurses during this period. Although not directly examined in our study, it is important to note that a substantial proportion of women in the United States identify as single mothers (U.S. Census Bureau, 2022). This may help explain why 62% of participants reported being the sole income providers for their households, a trend consistent with national data indicating that single-wage earners—especially single mothers—often experience limited economic resources (Kendig & Mathews, 2017).

Being single-wage earners results in fewer economic resources and less social and emotional support, compounding financial hardship (Center for Translational Neuroscience, 2020). Nurses' experience of low pay was further validated by Aguon and Phuong Le (2021), who interviewed five nurses and reported their perceptions of the inadequate compensation they received during the COVID-19 pandemic. Halcomb et. al. (2020) found that public health nurses had a concerning level of insecurity around nursing employment during the pandemic. Pressures on an already strained healthcare system resulted in workforce cutbacks, which made it difficult for many nurses to maintain financial stability, highlighting the urgent need for support during and after the pandemic.

Being single-wage earners results in fewer economic resources and less social and emotional support, compounding financial hardship

Our follow-up study results suggest factors contributing to the financial instability experienced by some nurses following COVID-19 circumstances. Our analyses consistently showed that physical health challenges were a significant predictor of financial instability. Using data from the Survey of Consumer Finances, Lyons and Yilmazer (2005) examined the relationship between health status and financial strain, finding that poor health significantly increases the probability of financial strain. However, there is a complex relationship between financial distress and health, with evidence also supporting that poor health can result from or result in financial distress, or both (O’Neill & Prawitz, 2006). A more recent study, Sujan et al. (2022), examined the financial hardship among people with underlying health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh. Their study showed that those with underlying health conditions experienced financial difficulties, which compounded debt and/or ability to cover medical expenses during the pandemic, with many experiencing multiple financial difficulties. Additionally, participants with underlying health conditions reported financial difficulties, with a higher prevalence of mental health conditions. French and McKillip (2017) found that the subjective experience of feeling financially stressed has a robust relationship with most aspects of health, including the ability to self-care, problems performing usual activities, pain problems, and psychological health. These findings highlight the need for targeted support to alleviate the financial burdens nurses may face while experiencing physical health problems, and mental health support to address the psychological impact of illness and financial distress.

Our analyses consistently showed that physical health challenges were a significant predictor of financial instability.

Interestingly, in our study, individuals experiencing long COVID-19 symptoms were less likely to face financial instability. This counterintuitive finding suggests that those who were able to seek care and identify their long COVID-19 condition may have been in a better financial position or have greater access to healthcare and resources. On the other hand, those reporting more general physical health challenges were more likely to experience financial difficulties, possibly reflecting the challenges faced by those unable to seek adequate care during the pandemic.

In contrast to the strain caused by physical health challenges, a strong support system emerged as a critical protective factor against financial instability. As shown in Table 2, the *Strong Support System Scale* had a significant negative coefficient of -0.332 (p < 0.001), indicating that nurses with stronger support networks were less likely to experience financial hardship.

...a strong support system emerged as a critical protective factor against financial instability.

Figure 8 further supports this, showing negative correlations between support systems and financial instability indicators, such as PostCOVIDBillPay (r = -0.32, p < 0.05) and Need for Financial Help (r = -0.27). The causal inference model in Figure 9 reinforces this buffering effect, with a path coefficient of -0.30, demonstrating that strong support systems help alleviate financial stress. Additionally, Table 3 shows that nurses who felt supported by their work colleagues experienced significantly reduced financial instability, with a coefficient of -0.554 (p = 0.025). These findings underscore that personal support and external financial aid, particularly from employers, can act as a vital buffer against the financial pressures nurses face during and after crises like the COVID-19 pandemic.

...nurses who felt supported by their work colleagues experienced significantly reduced financial instability...

The adequacy of salaries since COVID-19 has shown to be a key factor in financial stability. Table 3 demonstrates that nurses who reported their salaries as had a significant negative coefficient of -1.927 (p < 0.001), reflecting a notable reduction in financial instability. This underscores the importance of adequate compensation in maintaining financial security, particularly for nurses, where physical and emotional stress often intensifies financial pressures.

Beyond compensation, emotional health and family well-being also significantly impact financial outcomes. As seen in the causal inference model in Figure 9, the Emotional Health Challenges scale had a direct positive relationship with financial instability, with a path coefficient of 0.20, indicating that nurses struggling with emotional health were more likely to experience financial distress. Similarly, the FamilyDoingWell scale negatively correlated with financial instability (r = -0.28, p<0.05, Figure 9), suggesting that nurses whose families were doing well faced less financial distress. In contrast, nurses who reported that their families were not doing well experienced increased financial instability, as demonstrated by two items in Table 3. Specifically, the item " My immediate family member(s) still has/have physical health concerns from having COVID-19" had a positive coefficient of 0.415 (p < 0.05), indicating a higher likelihood of financial instability for those with family health challenges. Additionally, the item "My income is the only source of my or my family's economic support" had a positive coefficient of 0.775 (p < 0.001), further linking family struggles to increased financial burdens. These findings suggest that family challenges, whether related to health or financial support, played a substantial role in exacerbating financial instability.

The adequacy of salaries since COVID-19 has shown to be a key factor in financial stability.

Race played a significant role in financial outcomes, with clear disparities between racial groups. As illustrated in Table 2, identifying as White had a significant negative coefficient of -1.938 (p = 0.004), indicating that White nurses were less likely to experience financial instability, while Table 3 shows that Black nurses had a positive coefficient of 1.584 (p = 0.002), suggesting greater financial challenges. Figure 8 further supports this, showing that identifying as White was associated with less financial pressure. In the causal inference model depicted in Figure 9, the path coefficient of -0.14 between RaceWhite and NeedFinancialHelp indicates that White nurses were less likely to seek financial assistance. Similarly, the negative connection to DueCOVIDSeekFund in this diagram suggests that White nurses were less likely to seek alternative funds, such as second mortgages, loans, or retirement accounts, to cover their needs. This reduced financial strain may be due to higher household employment levels, as Figure 9 shows that this path contributes to less financial instability. Additionally, Figure 9 indicates that White nurses tended to have smaller households, which may have also contributed to their financial security. Still, these findings highlight systemic income and job security inequalities exacerbated by the pandemic.

Regional differences among nurses who applied for the Nurses House Inc. grant appear to have played a role in financial outcomes. New York nurses were more likely to experience financial stability, as indicated by the negative coefficient of -1.014 in Table 3. Although this result was not statistically significant (p = 0.074), it suggests a trend toward reduced financial instability for NY nurses compared to those from other states. This may reflect state-level support systems or relief measures in place during the COVID-19 pandemic that helped alleviate financial pressures for nurses in the region. Nurses from New Jersey and Louisiana also reported experiencing less financial pressure, as shown in Figure 8, while nurses from California and Indiana were associated with several key indicators of financial instability. Overall, the Northeast region nurses appeared more financially stable, as indicated in Figure 8. However, as shown in Figure 1, the majority of nurses in our sample were from New York, which could partly explain the observed regional disparities in financial stability.

Race played a significant role in financial outcomes, with clear disparities between racial groups.

Limitations of the study

This study used a non-random, purposive sample of previously self-selected nurses in 2020 who applied for an emergency grant, so it does not represent nurses in general. A response rate for the current follow-up survey of 14.5% also limits the generalizability of the findings to nurses who previously had experienced a financial crisis related to COVID-19. However, the themes and results do suggest areas for further exploration related to crisis situations and the financial stability of the nurse workforce.

Conclusions

The nurses who participated in this study experienced significant financial challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. Some nurses were financially resilient, while others experienced long-term financial impact. Those more financially vulnerable reported "living paycheck to paycheck." Many nurses who responded indicated needing to seek alternative funds during COVID-19, incurring considerable debt, and needing help to meet financial obligations. Interestingly, more than half replied that their annual salary before COVID-19 was adequate, but fewer felt it to be adequate since COVID-19.

These results underscore the importance of a financial safety net for professional nurses, given the demanding nature and potential for physical and emotional strain associated with nursing, which can be exacerbated by a serious emergency. A financial safety net typically includes savings, insurance, retirement plans, and other fiscal resources that can help individuals manage unexpected expenses or loss of income. Having a solid financial safety net can significantly enhance nurses’ well-being and in turn their professional practice. It can reduce stress and anxiety related to financial uncertainties, allowing nurses to focus more on patient care and professional development. Financial stability also provides freedom to make career choices based on passion and interest rather than financial necessity, which can lead to greater job satisfaction and longevity in the profession. Additionally, financial security allows a nurse to continue supporting primary and extended family members.

These results underscore the importance of a financial safety net for professional nurses...

The literature suggests that nurses face many challenges regarding financial security in general, without the added impact of a pandemic. These include, but are not limited to, unpredictable income due to varying work hours, overtime, or job changes and health risks due to higher hazards for workplace injuries and illnesses, which can lead to unexpected medical expenses or time off work, lack of job security especially during downturns, or changes in healthcare policies. Work-related stress, with high-stress levels leading to burnout, may also necessitate time off or even career breaks. Lastly, less than robust retirement planning may occur for those nurses who indicated they are living “paycheck to paycheck”. As seen in our study, some nurses are the main or sole provider for primary and extended family members. Many of these nurses indicated they had received no financial support besides the Nurses House, Inc. grant, while some received help from their family, fewer from friends, and rarely from their employers. Understanding the factors that impact the nurse's role can help inform policies that can support their professional and personal lives.

Unlike other first responder professionals...provisions were not in place to serve as a financial safety net for nurses.

During the recent pandemic, systems for this financial support were not in place for nurses legislatively and varied regionally and from facility to facility (Brennan, et al., 2023). Unlike other first responder professionals, such as police officers, emergency medical technicians, and firefighters, provisions were not in place to serve as a financial safety net for nurses. Legislation exists that supports other first responders injured during emergency situations; there are financial incentives and insurances that are offered; and disability insurances that protect against loss of income. Moving forward, planning for healthcare response should include provisions such as those in place for other first responders that support the financial health of nurses. The Nursing Human Capital Value Model (Yakusheva et al., 2024) asserts that nurses are an asset to be invested in and valued for their contributions to the healthcare system rather than a human resource to be managed and subjected to cost-minimization strategies that affect quality healthcare outcomes. In a global crisis such as a pandemic, it is the nurse workforce that is essential for the healthcare system to remain functional.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to acknowledge Susan M. Seibold-Simpson, PhD, MPH, RN, FNP, Research Specialist at the Center for Nursing Research at the Center for Nursing at the Foundation of NYS Nurses, and Adjunct Nursing Faculty, SUNYDelhi for her contribution to the study.

Errata Notice: The authors of “Financial Impact of COVID-19 on Nurses: A Follow-Up Study” published December 22, 2025, recently advised us that the author order published is incorrect. This article was amended on January 8, 2026 to reflect the correct order of authors in the article byline, citation, and the author biosketch listing.

Authors

Frances E. Crosby, EdD, MSN, RN

Email: fcrosby@niagara.edu

Dr. Crosby has a BS in Nursing from Niagara University, an MS in Child Psychiatric Nursing from Boston University and an EdD from State University of NY at Buffalo. She has been a nurse researcher with a focus on patient education and advanced practice nurse education. She has been a nurse educator and academic administrator, designing and executing the restart of baccalaureate nursing programs at the RN to BS, traditional four year, and accelerated second degree level. She is currently retired and awarded Professor and Dean Emeritus status at Niagara University.

Jerome Niyirora, PhD, RHIA

Email: jerome.niyirora@sunypoly.edu

ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8416-4165

Dr. Niyrirora is an Associate Professor at the Polytechnic Institute (SUNY Poly), where he teaches in the Health Informatics, Data Science and Analytics, and Health Information Management programs. He holds a PhD in Systems Science from SUNY Binghamton and an undergraduate degree in Health Information Management from SUNY Institute of Technology (now SUNY Poly). Dr. Niyirora is a Registered Health Information Administrator (RHIA). His research interests focus on integrating systems science models and machine learning techniques into healthcare analytics and the design of optimal healthcare systems

Rhonda Maneval, DEd, RN, ANEF, FAAN

Email: remaneval@carlow.edu

ORCID ID: 0000-0002-7895-1995

Dr. Maneval is the Interim Provost and the Dean of the College of Health and Wellness and School of Nursing at Carlow University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. She earned an MSN from Villanova University, and a Doctorate in Education from Pennsylvania State University. She has over thirty years in academic nursing education and has held multiple academic administrative positions. In addition, Dr. Maneval has secured extensive external funding to support nursing and health professions education students and programs. Her scholarship and expertise include curriculum development and evaluation, interprofessional communication and interprofessional practice competencies, and healthcare workforce issues

Linda Millenbach, PhD, RN

Email: lmillenbach@icloud.com

ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7922-133X

Dr. Millenbach obtained Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in Nursing from Russell Sage College in Troy, NY and a PhD from Adelphi University in Garden City, NY. She has held positions as a clinical nurse specialist, hospital administration and chair for a nursing education program. Her interests are education, research, leadership and innovation. Presently she is adjunct faculty at Empire/Utica University

Noreen B. Brennan, PhD, RN-BC, NEA-BC

Email: Nbrennan@pace.edu

Dr. Brennan is adjunct assistant professor at Pace University, New York and holds dual board certification in Medical/Surgical Nursing and Nursing Leadership Advanced from ANCC. Dr. Brennan is currently a member of the Boards of Nurses House and NYU nursing alumni.

Mary Anne Gallagher, DNP, RN-BC

Email: mag9383@nyp.org

ORCID: 0000-0002-1229-2050

Dr. Gallagher is the Director of Nursing for the Center for the Institute of Nursing Excellence and Innovation at NewYork-Presbyterian and Adjunct Faculty at Adelphi University. Dr. Gallagher is a Board member for Nurses House, Inc and Rory Myers College of Nursing, New York University alumni association.

Doreen Rogers, DNS, RN, CNE

Email: rogersd@canton.edu

Dr. Rogers is an Associate Professor and Chairperson at Utica University. She holds a graduate degree in Nursing Education from Mansfield University and a DNS from Sage Graduate School. She holds certifications in critical care nursing and as a nurse educator.

Kathleen Sellers, PhD, RN

Email: Sellerk@sunypoly.edu

Dr. Sellers is a Clinical Associate Adjunct Professor at SUNY Polytechnic and Utica University. She has numerous publications that focus on different aspects of nursing professional practice and presents regularly on these issues. She is a member of several professional nursing organizations including the NY Organization of Nurse Leaders and the Foundation of NYS Center for Nursing Research where she has served as Chair. She earned a BSN from Niagara University, a graduate degree in nursing from The Catholic University of America and a PhD from Adelphi University.

Deborah Elliott, MBA, BSN, RN

Email: delliott@cfnny.org

Deborah Elliott is the Executive Director of the Center for Nursing at the Foundation of NYS Nurses, Inc. and the Executive Director of Nurses House, Inc. She holds a Master’s in Business in Healthcare Administration from Union College, Schenectady, NY and a BSN from the State University of New York at New Paltz. Deborah has held various leadership positions since becoming licensed as an RN in 1979 including the Director of OB/GYN and Pediatrics at St. Clare’s Hospital in Schenectady, NY and the Deputy Executive Officer of the New York State Nurses Association

References

Aguon, D., & Phuong Le, N. (2021). A phenomenological study on nurses’ perception of compensation received during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Business and Management Research, 9(4), 443–447. https://doi.org/10.37391/IJBMR.090407

American Nurses Foundation. (2023). Annual assessment survey- The third year. Practice and Policy. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/work-environment/health-safety/disaster-preparedness/coronavirus/what-you-need-to-know/annual-survey--third-year

Bland, J. M., & Altman, D. G. (1997). Cronbach’s alpha. British Medical Journal, 314, 572. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.314.7080.572

Brennan, N. B., Gallagher, M. A., Elliott, D., Michela, N., & Sellers, K. (2023). Advocacy and policy in action: Developing a financial and healthcare safety net for nurses. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 55(1), 29–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12805

Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. (2024, March 12). Women’s earnings were 83.6 percent of men’s in 2023. TED: The Economics Daily. https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2024/womens-earnings-were-83-6-percent-of-mens-in-2023.htm

Center for Translational Neuroscience. (2020, November 11). Home alone: The pandemic is overloading Ssngle-parent families. RAPID Survey Project / Medium.https://rapidsurveyproject.com/article/home-alone-the-pandemic-is-overloading-single-parent-families/

Cvent®, Version 4.0 (2020). (Computer software). https://www.cvent.com

French, D., & McKillop, D. (2017). The impact of debt and financial stress on health in Northern Irish households. Journal of European Social Policy, 27(5), 458–473. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928717717657

Halcomb, E., McInnes, S., Williams, A., Ashley, C., James, S., Fernandez, R., Stephen, C., & Calma, K. (2020). The experiences of primary healthcare nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 52(5), 553–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12589

Hemez, P. F., Washington, C. N., & Kreider, R. M. (2024). America’s families and living arrangements: 2022 (Report No. P20-587). U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2024/demo/p20-587.html

Hyman, K. (2024, May 22). Why is there still a gender wage gap? Forbes Online. https://www.forbes.com/councils/forbesbusinesscouncil/2024/05/22/why-is-there-still-a-gender-wage-gap/

Kendig, S. M., & Mathews, T. J. (2017). The well-being of single mothers: Evidence from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study. Journal of Family Issues, 38(11), 1532–1555. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X17710286

Kurotani, A., Miyamoto, H., & Kikuchi, J. (2024). Validation of causal inference data using DirectLINGAM in an environmental small-scale model and calculation settings. MethodsX, 12, 102528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mex.2023.102528

Lindemann, N. (2024). What's the average survey response rate? Pointerpro. https://pointerpro.com/author/nigel-lindemann/#:~:text=What's%20the%20average%20survey%20response%20rate%3F%20%5B2021%20benchmark%5D&text=What%20is%20the%20average%20survey,33%2

Lyons, A. C., & Yilmazer, T. (2005). Health and financial strain: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances. Southern Economic Journal, 71(4), 873–890. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2325-8012.2005.tb00681.x

Millenbach, L., Crosby, F., Niyirora, J., Sellers, K., Maneval, R., Pettis, J., Brennan, N., Gallagher, M., & Michela, N. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on nurses—Where is the financial safety net? OJIN: Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 26(2), Manuscript 1. https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol26No02Man01

Millenbach, L., Maneval, R., Rogers, D. L., Sellers, K. F., Elliott, D., & Niyirora, J. (2023). Fellowship, finance, and fervor: Nurses caring for nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American Nurses Association - New York, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.47988/janany.53682868.3.1

Minitab® LLC (2021). Minitab Statistical Software, Version 21.4.3. State College, PA. https://www.minitab.com/en-us/support/minitab/minitab-software-updates/

O’Neill, B., Prawitz, A. D., Sorhaindo, B., Kim, J., & Garman, E. T. (2006). Changes in health, negative financial events, and financial distress/financial well-being for debt management program clients. Journal of Financial Counseling & Planning, 17(2), 46-63. https://www.researchwithnj.com/en/publications/changes-in-health-negative-financial-events-and-financial-distres/

Pearl, J., Glymour, M., & Jewell, N. P. (2016). Causal inference in statistics: A primer. Wiley. ISBN: 978-1-119-18686-1.

Pettis, J., Elliott, D., Michela, N., Brennan, N. B., & Gallagher, M. A. (2021, November 10). Who cares for the nurses who care for you? [blog]. American Journal of Nursing: Off the Charts. https://ajnoffthecharts.com/who-cares-for-the-nurses-who-care-for-you

Sujan, M, Tasnim, R., Islam, S., Haghighathoseini, A., Koly, K. N., Pardhan, S., et al. (2022). Financial hardship and mental health conditions in people with underlying health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh. Heliyon, 8(9), e10499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10499

Tavakol, M., & Dennick, R. (2011). Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. International Journal of Medical Education, 2, 53–55. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd

U.S. Census Bureau (2022, November). Census bureau releases new estimates on America’s families and living arrangements [press release]. News Releases. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2022/americas-families-and-living-arrangements.html

Yakusheva, O., Lee, K. A., & Weiss, M. (2024). The nursing human capital value model. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 160, 104890. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2024.104890