Burnout among nurses is prevalent and has worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic. Trauma-informed care (TIC) is an approach that can bring healing to people and systems who have been impacted by trauma and traumatic events. Nurses working in hospitals experience vicarious trauma and secondary traumatic stress as they witness what their individual patients experience; however, nurses themselves experience traumatic events and that has only escalated with the current pandemic. Working from a model of Trauma-Informed Healthcare (TIHC) and SAMSHA foundations of a trauma-informed approach (TIA) we identify opportunities for organizations such as hospitals to integrate TIA towards altering the system to better provide for nursing staff who are suffering from burnout and exhaustion. We offer an exemplar of an organizational-level approach to supporting nursing staff through TIA.

Key Words: Nurses, trauma-informed healthcare, trauma-informed approach, burnout, COVID-19, organization, hospital, stress, system-level, model

Although interventions to address the impact of stress, exhaustion, and burnout among nurses...do exist, many focus on supporting nurses only at the individual level.Nurses and the organizations where they work prioritize care not only for individuals, but also for communities and populations that experience illness or the threat of illness. While high rates of stress, exhaustion, and burnout existed prior to COVID-19, the additional workload of the ongoing pandemic has increased harm and stressful events for nurses working at the bedside in hospitals (Chan et al., 2021). Although interventions to address the impact of stress, exhaustion, and burnout among nurses (e.g., prioritizing self-care; training on delivery of trauma-informed care (TIC), coping with stress, or self-recognizing and preventing burnout) do exist, many focus on supporting nurses only at the individual level.

A systems level TIA has potential to provide support for nurses who have been exposed to traumatic events during the pandemic...We provide an overview about how using a trauma-informed approach (TIA) at the organizational or systems level could be implemented as an alternative to or concurrently with individual approaches to address burnout in nurses. A systems level TIA has potential to provide support for nurses who have been exposed to traumatic events during the pandemic and to prevent further harm to them. We present the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) principles of TIA and describe a model for trauma-informed healthcare (TIHC). Further, we suggest a systems-level perspective of the TIHC model that acknowledges the importance of nurses and the obligation of the organization to support them. Finally, we present an exemplar of nursing leadership from TIA.

Nurse Burnout and COVID-19

...burnout is associated with high turnover and reduced professional efficacy in healthcare settings.High rates of burnout have long plagued the United States (U.S.) healthcare workforce, with more than 50% of nurses experiencing burnout in the years prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (Galanis et al., 2021). Burnout is a combination of emotional exhaustion, cynicism towards one's patients, and negative views of oneself and one's work. Burnout can result from work-related stressors such as inefficient workplace processes, poor leadership and management, long work hours, heavy workload, and a lack of control in the workplace (Thumm et al., 2022). In addition to its adverse effects on personal well-being, burnout is associated with high turnover (and therefore poor job retention) and reduced professional efficacy in healthcare settings (Shanafelt & Noseworthy, 2017). Other workforce stressors, such as structural inequities, implicit bias, discrimination, and sexual harassment, also contribute to burnout and poor job retention in the field (Adesoye et al., 2017).

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, scientists recognized its likely long-lasting impacts on individual mental health. Nurses in particular experienced high levels of emotional and psychological distress, pointing to the urgent need for prevention and treatment strategies (Chan et al., 2021; Gunnell et al., 2020). A recent review and meta-analysis that examined psychological effects of emerging virus outbreaks on healthcare workers found evidence of high psychological morbidity (Kisely et al., 2020). Studies, including systematic reviews, have shown that healthcare workers who are especially vulnerable to psychological sequelae during the COVID-19 pandemic include younger workers, women, frontline workers (especially nurses), caregivers, people of color, and those who are socially isolated, of low socio-economic status, with less training, or at high risk of contracting COVID-19 (Galanis et al., 2021; Kisely et al., 2020; Luo et al., 2020).

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, scientists recognized its likely long-lasting impacts on individual mental health.A recent survey of California healthcare staff found that frontline workers reported experiencing increasing amounts of frustration and weariness as the COVID-19 pandemic continues (California Health Care Foundation, 2021). Nurses especially reported increasing levels of burnout as they continue to care for those hospitalized with COVID-19 while also continuing to report shortages of personal protective equipment and staff. The authors stated that California’s providers in healthcare are fed up and under strain (California Health Care Foundation, 2021). Notably, nurses have the highest rate of contracting COVID-19 when compared to other healthcare staff. Nurses are expected to perform patient care with fortitude and empathy in an environment that can be high stress, including fear of exposure to themselves and their families (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2020). Twelve-hour shifts under stressful conditions can result in exhaustion, injury, and job dissatisfaction. These conditions are amplified by an existing nursing shortage that varies by U.S. region and is expected to reach a shortfall of greater than 100,000 registered nurses by 2030 (Juraschek et al., 2019).

Supporting Nurse Workforce with Trauma-Informed Approaches

In contrast to more general burnout, vicarious trauma and secondary traumatic stress occur specifically when working with populations that experience trauma (Newell & MacNeil, 2010). SAMHSA defines trauma as “an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being” (SAMHSA, 2014, p.7). Nimmo and Huggard (2013) define vicarious trauma as “the undesirable outcomes of working directly with traumatised populations” (p.38) occurring over time, and define secondary traumatic stress as a more immediate “stress response resulting from witnessing or knowing about the trauma experience by … others” (p.39).

In contrast to more general burnout, vicarious trauma and secondary traumatic stress occur specifically when working with populations that experience trauma.There is considerable evidence that traumatic exposure can lead to chronic health problems such as depression, substance use disorder, and heart disease (Felitti et al., 1998). Nurses may encounter trauma while working in a range of settings such as emergency departments, intensive care units, or conflict areas. Trauma can include physical or emotional abuse as a child or adult, natural disasters such as wildfires, or the sudden death of a loved one. It can also be considered more broadly to include structural violence such as racism or poverty (Egede & Walker, 2020). More recently, nurses may have cared for populations experiencing trauma due to COVID-19, including people who were hospitalized, who had to be isolated from their families and partners, and who were at serious risk of death from the disease.

Nurses described the [pandemic] experience as overwhelming beyond anything they had experienced...Considering the experience of nurses across the evolution of the current COVID-19 pandemic, there is evidence that they themselves have experienced the pandemic as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and therefore traumatic, and that this has had an effect on their functioning (Robinson & Stinson, 2021). Nurses experienced the pandemic as traumatic to themselves due to risk of contracting COVID-19 from patients, lack of adequate personal protective equipment, and fear of bringing the disease home to their families. At the same time, they may have experienced secondary traumatic stress from having patients die alone without having their families around, or vicarious trauma from working over the course of the pandemic with patients who were so critically ill and scared. Nurses described the experience as overwhelming beyond anything they had experienced, coping by just doing, and not having any feelings; some have likened their experience to that of being in a war. A recent review of studies indicates that risk factors for acquiring COVID-19 and mental health symptoms were greater for women and nurses in particular, and included moderate to severe anxiety, stress disorders, insomnia, and depression (Shaukat et al., 2020).

...institutional and structural-level trauma-informed approaches are needed to address the impacts of trauma on nurses and the larger nursing profession.Using the case of nurses with experiences of burnout, vicarious trauma, and secondary traumatic stress, all of which have been exacerbated during COVID-19 pandemic, we can begin to see how the pandemic affected both individual nurses and by extension the nursing profession. And as our understanding of how trauma is linked to lifelong health has grown, so has the knowledge that we need to change our response to the traumatic exposures that nurses experience as part of their occupation. We suggest that institutional and structural-level trauma-informed approaches are needed to address the impacts of trauma on nurses and the larger nursing profession.

The Concept of Trauma

TIAs are based on the premise that people must feel safe in order to reach their highest potential.TIAs are based on the premise that people must feel safe in order to reach their highest potential. As described by SAMHSA, “A program, organization, or system that is trauma-informed realizes the widespread impact of trauma and understands potential paths for recovery; recognizes the signs and symptoms of trauma in clients, families, staff, and others involved with the system; and responds by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices, and seeks to actively resist re-traumatization” (SAMHSA, 2014, p.9). SAMHSA further describes six principles of TIA that can be used as part of creating trauma-informed organizations (see Table 1). These principles are important to consider as we design an occupational system and setting for nurses exposed to trauma.

Table 1. Six Key Principles of a Trauma-Informed Approach

|

Principle |

Key Organizational Description |

|

Safety |

“Throughout the organization, staff [nurses and other health workers] and the people they serve… [hospitalized patients] feel physically and psychologically safe.” |

|

Trustworthiness and Transparency |

“Organizational operations and decisions are conducted with transparency with the goal of building and maintaining trust with clients and family members, among staff, and others involved in the organization.” |

|

Peer Support |

“Peer support and mutual self-help are key vehicles for establishing safety and hope, building trust, enhancing collaboration, and utilizing their stories and lived experience to promote recovery and healing.” |

|

Collaboration and Mutuality |

“Importance is placed on partnering and the leveling of power differences … among organization staff from clerical and housekeeping personnel to professional staff to administrators, demonstrating that healing happens in relationships and in the meaningful sharing of power and decision-making.” |

|

Empowerment, Voice, and Choice |

“Throughout the organization… individuals’ strengths and experiences are recognized and built upon…. Organizations understand the importance of power differentials and ways in which clients [and staff], historically, have been diminished in voice and choice and are often recipients of coercive treatment.” |

|

Cultural, Historical, and Gender Issues |

“The organization actively moves past cultural stereotypes and biases…; offers access to gender responsive services; leverages the healing value of traditional cultural connections; incorporates policies, protocols, and processes that are responsive to the racial, ethnic and cultural needs of individuals served; and recognizes and addresses historical trauma.” |

(SAMHSA, 2014, p.11)

Trauma-Informed Approach Within Healthcare Settings

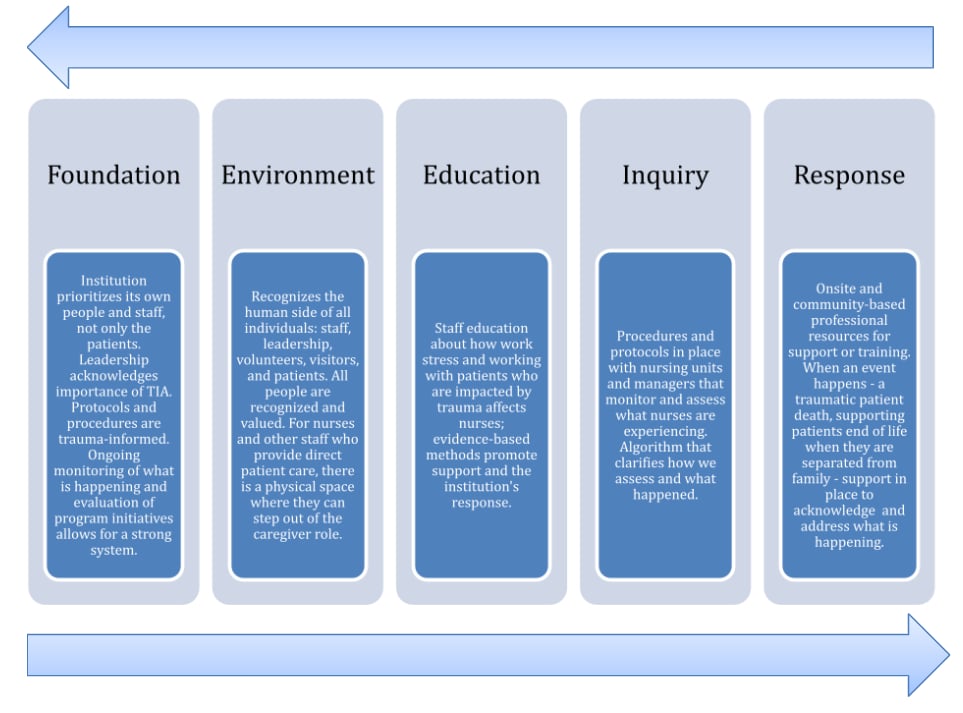

In 2013, a group of national experts came together to begin work on a model to address trauma within a healthcare clinic. Although focused on a specific primary care setting, the elements of the model serve as a strong foundation and guide to address burnout, vicarious trauma, and secondary traumatic stress among nurses. An update of the model describes five core elements of TIHC all of which benefit not only the patient but also nurses and other clinical and behavioral healthcare givers (Machtinger et al., 2015, 2019). We have adapted these elements to describe how they can be used to address burnout among nurses (see Figure).

Simple physical and organizational adaptations in a clinical setting can reduce triggers...The basis of the TIHC model is a strong Foundation of trauma-informed values such as those described by SAMHSA; a team-based approach to care; strong leadership and organizational buy-in; and training, supervision, and support for staff. These elements describe organizational and structural-level approaches to prevent burnout among nurses and other providers in the context of, for example, a global pandemic or work with particularly vulnerable populations. The second element of the model is an Environment that is safe, calm, and empowering for patients and staff. Simple physical and organizational adaptations in a clinical setting can reduce triggers and set the stage for calmer interactions between patients and staff, as well as among staff. Education for both patients and staff addresses the linkages between past and current trauma and health and includes the impact of work-related stress on burnout and other longer-term health conditions.

We must remember that nurses and other staff are also patients in their own lives...Building on education around the impact of trauma, Inquiry provides the opportunity to screen for both current and past trauma and toxic stress. Using a structured instrument or a more conversation-based approach allows individuals to disclose experiences as they are most comfortable and when they are ready. Finally, the Response to disclosures of trauma or toxic stress begins with understanding and empathy. For patients, the response may then include referrals to on-site or community-based services. We must remember that nurses and other staff are also patients in their own lives, and thus should experience a similar model of care in that context.

Within the work context, the initial response to disclosures of trauma and burnout by nurses and other staff may include referrals to organization-based supports such as staff assistance programs, onsite staff counseling, or additional clinical supervision. Such a response to trauma and burnout, however, does not fully address institutional and structural-level issues such as nursing shortages, high patient-nurse ratios, and longer-term situations such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure. Model of TIHC Adapted for Systems Level Factors

(Adapted from Machtinger et al., 2015, 2019)

[View full size]

...nurses and other care providers were ready for trauma-informed approaches...but the larger health systems within which they function were not ready...Together, the SAMHSA concept of trauma and the TIHC model provide a useful framework to understand how organizations can better serve nurses and other healthcare providers and staff who are experiencing burnout, vicarious trauma, and secondary traumatic stress. Other systems such as juvenile justice, schools, and behavioral health provide examples of effective integration of TIA (Beidas et al., 2016; van der Kolk, 2003). In our own experience we have found that nurses and other care providers were ready for trauma-informed approaches and for changing the way they work, but the larger health systems within which they function were not ready and could produce barriers (Dawson-Rose et al., 2019). For example, in some cases, trauma-informed care was siloed within an institution which impeded structural change at the organizational level (Portelli Tremont et al., 2021). While staff training is an important step to move the approach forward, training is often focused only on treating patients; instead, what is needed is training on how this approach can also impact and improve well-being for nurses themselves. The following is an example of integrating a trauma-informed management model for nurses.

Exemplar: Trauma-Informed Intensive Care Unit Nurse Management Model

Large, urban, non-profit institutions have offered many opportunities for leaders and frontline staff to receive training on what TIC means, including recognition of our most vulnerable populations and identifying benefits of this type of care. Training focuses on the in-patient and out-patient populations within the health system. Unit directors, managers, and leaders in in-patient settings, such as intensive care units, should consider the population of interest to be nursing staff, department-based ancillary staff, advanced practice providers, and physicians who care for these patients. The intensive care patient population is considered high risk for cardiac arrest and mortality. Providers who care for this patient population are frequently engaged in rescue attempts, resuscitation, and end-of-life scenarios.

...training is often focused only on treating patients; instead, what is needed is training on how this training can also impact and improve well-being for nurses themselves.The long-standing perspective on these work-place experiences has been, “it’s part of the job.” Work-place injury prevention has been a primary focus of public health over the past 25 years; however, this injury prevention has focused on physical injury with little consideration for mental, social, emotional, and ethical injury. Nursing staff in intensive care units have reported a high prevalence of burnout, moral distress, and even consideration of career path changes. This has inspired individuals in leadership positions to take a unique approach to trauma-informed nursing management.

It may be the responsibility and passion of nursing leaders to help all nurses achieve their highest potential. This can only be achieved through the creation of a safe place for each nurse. This sense of safety can be achieved by the following process inputs and outcomes highlighted in Table 2.

Table 2. Process Inputs and Outcomes of a Trauma-Informed ICU Nurse Management Model

|

Process Inputs |

Process Outcomes |

|

Monthly updates on staffing status and opportunities to participate in peer panel interviews. |

|

|

Staff education on implicit bias, ladder of inference, and closed loop social-emotional communication. |

|

|

Office Hours: Dedicated time for staff to use 30-minute increments for anything they want offered twice a week. The focus of the time is to allow the team to be heard, offer support, and allow for opportunity to contribute to necessary change as needed. |

|

|

Quarterly community building events to establish and then model appropriate supportive conversations. |

|

|

Modeling, encouragement, and opportunity for transparency regarding personal impact of emotionally charged conversations and experiences while caring for the pediatric cardiac population in the form of complex care experience debriefings held monthly. |

|

|

Staff education on the Strategic Plan, transparency of challenges, and opportunity to share responsibility for problem solving. |

|

|

Establishment of Communication Standards and reparative pathways. |

|

Limiting exposure and supporting nurses through trauma is key to preventing burnout.As seen in this exemplar, foundations of trauma-informed care are applied to nursing management practice. With this implementation, leaders will continue to evaluate the burnout status of staff as they continue to recover from the initial pandemic and learn to live in a new healthcare setting. Managers do not need to be experts in the field they manage; however, if managers also wish to be department level leaders, they must have a full appreciation for the trauma that their team members have and will continue to experience. Limiting exposure and supporting nurses through trauma is key to preventing burnout.

Conclusion

Motivating policy change, education, and innovative approaches at the institutional level is equally important.As the COVID-19 pandemic continues and we face new emerging infections and health system challenges, we must act. Nurse scholars and leaders must seek new methods to prevent burnout and cumulative injuries to nurses currently working at the bedside and to retain and recruit the next generation of nurses entering a profession that demands extraordinary commitment. Examples within have been used to highlight different systems-level trauma-informed approaches to respond to stress and mental health symptoms of providers who have endured the pandemic demands. Integrating TIA at the organizational level within the healthcare system is essential. Motivating policy change, education, and innovative approaches at the institutional level is equally important.

Nurse burnout has been amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic. This is a call to all nurse leaders to bring systems-level trauma-informed approaches to organizations where nurses work -- where nurses and other healthcare staff are exposed to patients experiencing trauma, and where they experience trauma themselves.

Authors

Carol Dawson-Rose, RN, PhD, FAAN

Email: carol.dawson-rose@ucsf.edu

ORCID ID: 0000-0001-6066-1853

Carol Dawson-Rose is Professor and Chair in the Department of Community Health Systems at University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) School of Nursing. Her research is centered on improving equity in care for people living with HIV who use drugs. Dr. Dawson-Rose’s current projects consider how to implement trauma-informed approaches in HIV primary care settings, substance use services, community-based HIV services for sexual and gender minority transitional age youth, and public health nursing practice. She participated in the development of the model of Trauma Informed Healthcare.

Yvette Cuca, PhD, MPH, MIA

Email: yvette.cuca@ucsf.edu

ORCID ID: 0000-0002-5674-4741

Yvette Cuca is a sociologist in the UCSF School of Nursing Department of Community Health Systems. She has over 20 years of experience in domestic and international research and program evaluation. Her recent research has focused on the impact of trauma on patients and on the providers and staff who care for them. Dr. Cuca also investigates the ways that trauma-informed approaches may improve health and social outcomes for patients and improve work life for healthcare staff.

Shanil Kumar, MPH

Email: shanil.kumar@ucsf.edu

Shanil Kumar is an analyst in the UCSF School of Nursing Department of Community Health Systems. He has 6 years of experience studying health sciences and public health specifically examining factors affecting vaccine uptake. Shanil has experience in policy, prevention, and planning with the Merced Department of Public Health as well as tobacco cessation efforts in the Central Valley with the American Cancer Society. More recently, Shanil has been involved in the recruitment, planning, and coordinating of focus groups investigating trauma, resiliency, and cultural and social influences of Indo-Fijians in the Central Valley.

Angela Collins, MPH, BSN, RN

Email: angela.collins@ucsf.edu

Angela Barbetta Collins has been a pediatric ICU nurse for 18 years and a Nurse Manager for 5 years. She is currently the Unit Director of the Pediatric Cardiac ICU and CTCU at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital. She also held clinical positions at Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago. Angela is completing a MPH at the University of California Berkeley. Her primary patient population of focus is Pediatric Congenital Heart Defects and Pediatric Cardiac Surgery. She is a UCSF DEI Champion, trained in Trauma Informed Care, and developed the Trauma Informed ICU Nurse Management Model.

References

Adesoye, T., Mangurian, C., Choo, E. K., Girgis, C., Sabry-Elnaggar, H., Linos, E., & Physician Moms Group Study Group. (2017). Perceived discrimination experienced by physician mothers and desired workplace changes: A cross-sectional survey. JAMA Internal Medicine, 177(7), 1033–1036. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1394

Bandyopadhyay, S., Baticulon, R. E., Kadhum, M., Alser, M., Ojuka, D. K., Badereddin, Y., Kamath, A., Parepalli, S. A., Brown, G., Iharchane, S., Gandino, S., Markovic-Obiago, Z., Scott, S., Manirambona, E., Machhada, A., Aggarwal, A., Benazaize, L., Ibrahim, M., Kim, D., … Khundkar, R. (2020). Infection and mortality of healthcare workers worldwide from COVID-19: A systematic review. BMJ Global Health, 5(12), e003097. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003097

Beidas, R. S., Adams, D. R., Kratz, H. E., Jackson, K., Berkowitz, S., Zinny, A., Cliggitt, L. P., DeWitt, K. L., Skriner, L., & Evans, A. (2016). Lessons learned while building a trauma-informed public behavioral health system in the City of Philadelphia. Evaluation and Program Planning, 59, 21–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2016.07.004

California Health Care Foundation. (2021, February 17). Burnout growing among health care workers as pandemic wears on. California Health Care Foundation. https://www.chcf.org/press-release/burnout-growing-among-health-care-workers-as-pandemic-wears-on/

Chan, G., Bitton, J., Allgeyer, R., Elliott, D., Hudson, L., & Moulton Burwell, P. (2021). The Impact of COVID-19 on the Nursing Workforce: A National Overview. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 26(2). https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol26No02Man02

Dawson-Rose, C., Cuca, Y. P., Shumway, M., Davis, K., & Machtinger, E. L. (2019). Providing primary care for HIV in the context of trauma: Experiences of the health care team. Women’s Health Issues, 29(5), 385–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2019.05.008

Egede, L. E., & Walker, R. J. (2020). Structural racism, social risk factors, and Covid-19—A Dangerous convergence for Black Americans. The New England Journal of Medicine, 383(12), e77. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2023616

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245-258.

Galanis, P., Vraka, I., Fragkou, D., Bilali, A., & Kaitelidou, D. (2021). Nurses’ burnout and associated risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 77(8), 3286–3302. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14839

Gunnell, D., Appleby, L., Arensman, E., Hawton, K., John, A., Kapur, N., Khan, M., O’Connor, R. C., Pirkis, J., Appleby, L., Arensman, E., Caine, E. D., Chan, L. F., Chang, S.-S., Chen, Y.-Y., Christensen, H., Dandona, R., Eddleston, M., Erlangsen, A., … Yip, P. S. (2020). Suicide risk and prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(6), 468–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30171-1

Juraschek, S. P., Zhang, X., Ranganathan, V., & Lin, V. W. (2019). Republished: United States registered nurse workforce report card and shortage forecast. American Journal of Medical Quality, 34(5), 473–481. https://doi.org/10.1177/1062860619873217

Kisely, S., Warren, N., McMahon, L., Dalais, C., Henry, I., & Siskind, D. (2020). Occurrence, prevention, and management of the psychological effects of emerging virus outbreaks on healthcare workers: Rapid review and meta-analysis. BMJ, 369, m1642. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1642

Luo, M., Guo, L., Yu, M., Jiang, W., & Wang, H. (2020). The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public – A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 291, 113190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113190

Machtinger, E. L., Cuca, Y. P., Khanna, N., Rose, C. D., & Kimberg, L. S. (2015). From treatment to healing: The promise of trauma-informed primary care. Women’s Health Issues, 25(3), 193–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2015.03.008

Machtinger, E. L., Davis, K. B., Kimberg, L. S., Khanna, N., Cuca, Y. P., Dawson-Rose, C., Shumway, M., Campbell, J., Lewis-O’Connor, A., & Blake, M. (2019). From treatment to healing: Inquiry and response to recent and past trauma in adult health care. Women’s Health Issues, 29(2), 97–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2018.11.003

Newell, J. M., & MacNeil, G. A. (2010). Professional burnout, vicarious trauma, secondary traumatic stress, and compassion fatigue. Best Practices in Mental Health, 6(2), 57–68.

Nimmo, A. and Huggard, P. (2013). A systematic review of the measurement of compassion fatigue, vicarious trauma, and secondary traumatic stress in physicians. Australian Journal of Disaster and Trauma Studies, 2013(1), 37-44.

Portelli Tremont, J. N., Klausner, B., & Udekwu, P. O. (2021). Embracing a trauma-informed approach to patient care - In with the new. JAMA Surgery, 156(12), 1083. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2021.4284

Robinson, R., & Stinson, C. K. (2021). The lived experiences of nurses working during the COVID-19 pandemic. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing, 40(3), 156–163. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCC.0000000000000481

Shanafelt, T. D., & Noseworthy, J. H. (2017). Executive leadership and physician well-being: Nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clinic ShahProceedings, 92(1), 129–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.004

Shaukat, N., Ali, D. M., & Razzak, J. (2020). Physical and mental health impacts of COVID-19 on healthcare workers: A scoping review. International Journal of Emergency Medicine, 13(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-020-00299-5

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach (HHS Publication No. 14-4884; pp. 9–11). https://ncsacw.acf.hhs.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf

Thumm, E. B., Smith, D. C., Squires, A. P., Breedlove, G., & Meek, P. M. (2022). Burnout of the US midwifery workforce and the role of practice environment. Health Services Research, 57(2), 351–363. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13922

van der Kolk, B. A. (2003). The neurobiology of childhood trauma and abuse. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics, 12(2), 293–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1056-4993(03)00003-8