Reimbursement parity of nurse practitioners (NPs) and physicians is appropriate now more than ever. Studies have demonstrated that NPs provide the same quality of care as physicians, yet they do not receive the same reimbursement. The rise in full practice authority states, as well as nurse managed clinics and retail clinics, has led to more NPs practicing independently. The COVID-19 pandemic opened a need for NPs to provide a greater amount of care in more settings, and thus led to temporary removals of practice restrictions to increase access to care. This article offers a review of the issues, such as “incident to” billing; direct and indirect reimbursement; and quality of care. We consider MedPAC and reimbursement policy, post COVID-19 policy solutions, and action steps to move forward to seek reimbursement parity. The COVID-19 pandemic serendipitously led to the removal of many restrictions on NP practice, offering an opportunity for NPs to work with MedPAC to achieve full reimbursement for care provided.

Key Words: nurse practitioner, advanced practice provider, nursing reimbursement, MedPAC, COVID-19, nurse managed health centers, retail clinics, “incident to” payment, full scope of practice, Medicare

There is a crucial need to equate the primary care reimbursement for all primary care providers.The current Medicare reimbursement policy for nurse practitioners (NPs) should be changed to allow 100% reimbursement for care rendered by NPs. The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 granted NPs the ability to directly bill Medicare for services that they perform. However, reimbursement is only provided at 85% of the physician rate. There is a crucial need to equate the primary care reimbursement for all primary care providers.

Over the past decade, the number of NPs has dramatically increased, from 120,000 in 2007 (American Association of Nurse Practitioners [AANP], 2018) to 290,000 in 2019 (AANP, 2020). Their role in healthcare has also evolved. Today, many more states have granted NPs full practice authority, including prescriptive privileges. NPs also have more independent roles as they now lead nurse-managed health centers and retail clinics. NPs have demonstrated the ability to provide healthcare in a variety of settings, including rural areas and underserved communities, and to serve vulnerable populations, including older adults and those with low income (See Table 1).

Table 1.

Why Should Nurse Practitioners Receive 100% Reimbursement?

|

Pros |

Cons |

Rationale |

|

The role of the NP has expanded in the last two decades. NPs are more likely to care for patients in areas that have been traditionally underserved by physicians (Nickerson, 2014). NPs now run rural health clinics, nurse managed centers and retail clinics (Hansen-Turton et al., 2010). |

Physicians have higher cost associated with training, office overhead, and malpractice premiums (MedPAC, 2019b). |

The number of NPs has grown rapidly from 120,000 in 2007 (AANP, 2018) to 290,000 in 2019 (AANP, 2020), while the number of physicians working in primary care has decreased (Cheney, 2018). |

|

NPs now have full practice authority in 23 states and more states have pending legislation (AANP, 2021). |

Certain procedures can only be performed by a physician and need referral for those specialized medical procedures (MedPAC, 2002). |

NPs increase access to care. With the growing number of states permitting full access authority to NPs, there is an increase in both nurse managed clinics and retail clinics. COVID-19 has led to even more states temporarily removing restrictions on NP practice as an effort to increase patient access to care (Zolot, 2020). |

|

NPs provide quality, cost effective care (Barnes et al., 2016; Kippenbrock et al., 2019; Naylor & Kurtzman, 2010). |

NP salaries are less than physician salaries (MedPAC, 2019a). NPs can bill “incident to” and receive 100% reimbursement. |

NPs are doing much of the same work as their physician colleagues (Sullivan-Marx, 2008); therefore, they should receive the same reimbursement. When NPs bill “incident to”, data does not accurately reflect the types of patients that they treat, since the physician is credited for the patient visit, not the NP (Rapsilber, 2019). |

The COVID-19 pandemic has further supported the independent role of NPs.The COVID-19 pandemic has further supported the independent role of NPs. In addition to the 23 states plus the District of Columbia that previously granted full practice authority for NPs (AANP, 2021), 19 states temporarily removed some, if not all, practice restrictions in May 2020. This allowed NPs to practice at the full scope of their license and certification and assume a more autonomous role in caring for the increased number of patients who sought care during the pandemic. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) also expanded the roles of NPs, allowing them to provide services previously only permitted by physicians (Zolot, 2020) (See Tables 1 and 2).

Table 2.

Frequently Asked Questions

|

Question |

Answer |

|

Why do NPs get reimbursed less than medical doctors for the same care? |

The 85% reimbursement policy is supported by the rationale that physicians have higher student loans, pay practice overhead cost, have higher malpractice premiums, and care for more complex patients (MedPAC, 2002). While this may have been the case in the past, currently, NPs also have student loans, pay practice overhead costs when they manage their own practices, have malpractice premiums that vary per specialty area, and care for complex patients (Edmunds, 2014). Patient complexity is difficult to discern because many NPs bill “incident to”, thus a true patient panel is difficult to evaluate (MedPAC, 2019a). |

|

How does “incident to” billing affect NP practice? |

Medicare will reimburse NP care at 100% if the visit is billed as “incident to” rather than under the NPs own NPI number. When NPs bill as “incident to,” the care is attributed only to the physician, thus masking the accuracy of the types of visits and numbers of patients actually seen by NPs (Rapsilber, 2019). |

|

Why is the Medicare reimbursement rate for NPs still 85%? |

MedPAC met in 2002 and determined that NP care is not equivalent to physician care. Thus, their recommendation was to continue with the 85% reimbursement rate (MedPAC, 2002). In their 2019 meeting, MedPAC recognized that “incident to” billing masks the true care provided by NPs and recommended stopping “incident to” billing. Congress has not acted on this recommendation (MedPAC, 2019a). |

|

Why is the 85% reimbursement rate detrimental to NPs? |

The 85% rule is particularly detrimental to NPs who own their own practice. The decrease in reimbursement results in financial instability and decreased employment opportunities, in addition to decreased recognition of the value of NP visits and care (Chapman et al., 2010). |

|

What policies promote improved reimbursement? |

Healthcare has undergone many changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic. To decrease barriers to care, many states temporarily lifted practice restrictions on NPs to allow them to practice to the full extent of their license. Since the pandemic began, several states have voted to permit permanent full practice authority to NPs. With the increase in independence, it becomes even more crucial that NPs receive full reimbursement for their services (Zolot, 2020). |

Research has shown that NPs provide quality, cost effective care with a favorable patient experience (Kippenbrock et al., 2019) (See Table 1). Given the increased role of NPs, and their ability to provide care comparable to physicians, Congress should allow Medicare to increase the NP reimbursement rate to equate to 100% of the physician pay rate.

Review of The Issues

“Incident to” Billing

NPs have been providing care for Medicare patients since its inception in1965.NPs have been providing care for Medicare patients since its inception in1965. However, reimbursement for their services has been a journey. Initially, care delivered by NPs was billed under the physician’s name as “incident to” payment. Under “incident to” payment, a non-physician provider (NPP), such as an NP, certified nurse midwife (CNM) or physician assistant (PA), renders the care, but the visit is billed under the physician’s name. Medicare reimburses 100% for services billed as “incident to.”

To bill this way, certain rules must be followed. First, the patient must have already established care with the physician. Therefore, NPPs cannot see new patients and bill “incident to.” Second, treatment for a specific problem must have already been initiated by the physician, so NPPs cannot see the patient for a new problem. Third, the care must be rendered under the direct supervision of the physician. This means that the physician needs to be in the office suite, although not necessarily directly in the room with the patient (Shay, 2015).

“Incident to” billing practices are still in effect today. “Incident to” billing practices are still in effect today. If the requirements are fulfilled, NPPs can render care while billing under the physician’s name, and CMS will provide reimbursement for the visit at 100%. While this form of billing renders a higher reimbursement to the practice, it undermines important, quality NPP work because only the physician’s name appears on the claim. This inhibits the ability to track the number of patients assessed and managed by NPPs (Rapsilber, 2019).

Although CMS rules refer to Medicare billing, other insurance companies often base their billing practices on CMS guidelines (Edmunds, 2014). Therefore, “incident to” requirements, as well as the 85% reimbursement rule, often are also followed by Medicaid and commercial insurers. If ’incident to” billing rules are not followed, both the NP and the physician are susceptible to fines and/or other repercussions for fraudulent billing (Rapsilber, 2019). What this means in practice is that many practice owners would rather see NPs bill “incident to” than under their own provider number. Why would anyone running a practice want to lose 15% of revenue for every patient that the NP sees?

Direct Reimbursement

...without a physician on-site, NPPs were unable to receive any reimbursement for their services.In the 1970s, many physicians who practiced in rural areas began to retire and there was a lack of younger physicians to fill the vacancies. Residents in these communities were often older adults, minorities, and low-income populations traditionally with significant healthcare needs. During this same time, there was a surge of NPs and PAs. These providers were able to fill the physician void in many communities (Nickerson, 2014). However, without a physician on-site, NPPs were unable to receive any reimbursement for their services.

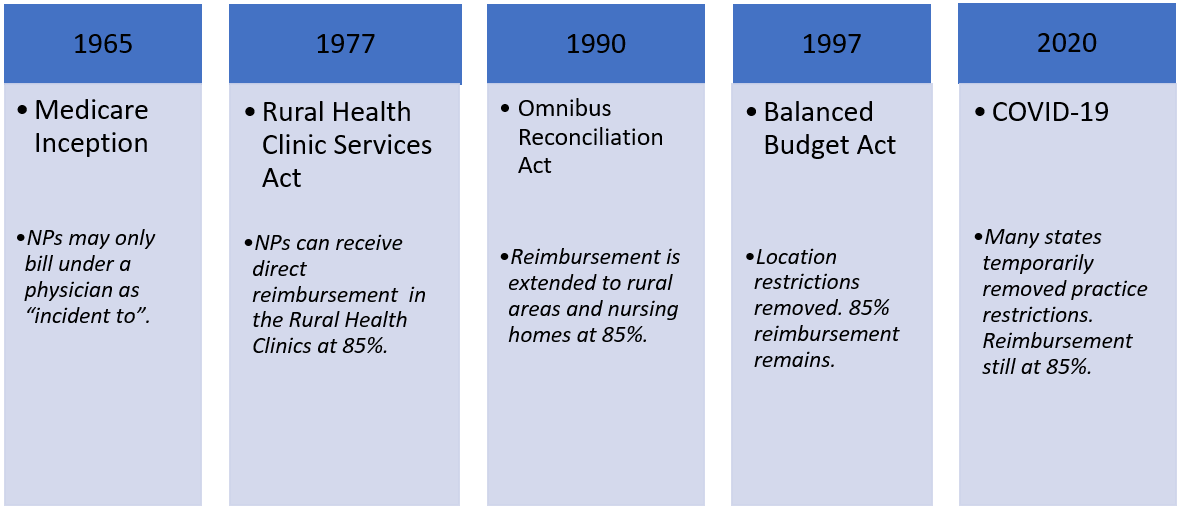

The Rural Health Clinic Services Act (1977) helped to rectify the situation. This act established Rural Health Clinics (RHCs) to provide care in these areas, and it also recognized care delivered by NPs and PAs. As a result, for the first time, NPs, CNMs, and PAs were able to receive direct reimbursement from CMS. CNMs received reimbursement of 65%, while NPs and PAs received reimbursement of 85% of the physician rate (Figure 1).

Indirect Reimbursement

The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) (1990) further supported NPPs by providing direct reimbursement for care in rural areas and indirect reimbursement for care in nursing homes, at 85% of the physician rate (Sullivan-Marx, 2008). The Balanced Budget Act (1997) removed location restrictions from NPP reimbursement. This meant that all NPs could bill Medicare directly for services that they provided for patients, regardless of where those services were provided. (See Figure 1 for a timeline that depicts the historical governmental policies that have affected NP reimbursement policies from CMS.

Figure. History of Nurse Practitioner (NP) Reimbursement from Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)

Unfortunately, CMS did not change the reimbursement rate. “Incident to” rules also remained in effect. Therefore, NPPs have a choice: bill under their own provider number and receive 85% reimbursement and accurately track NP-specific practice trends and payments or, satisfy the “incident to” rules and receive 100% reimbursement (Chapman, Wides, & Spetz, 2010). This is important because, if billing under the physician’s provider number, the NPP’s name never appears in the billing records. Therefore, it is difficult for payers and the public to recognize the productivity of the NPP (Medicare Payment Advisory Commission [MedPAC], 2019a) (See Table 1). Recognition of this productivity by both parties is crucial for NPPs to receive parity for equal services.

Recognition of this productivity by both parties is crucial for NPPs to receive parity for equal services.A study conducted by the RAND corporation found that the average cost of an NP visit was 20-35% lower than that of a physician visit (Naylor & Kurtamam, 2010). However, it is often difficult to measure the true economic impact of care performed by NPs because of “incident to” billing. If a visit is billed as “incident to,” only the physician’s name is associated with that visit. This makes the NP “invisible” from the billing standpoint and can make it difficult to accurately identify patients who received care provided by NPs (Rapsilber, 2019) (See Table 2).

Quality of Care

Throughout the fight for NPs to receive reimbursement from CMS, the quality of care that NPs provide has been studied extensively. As stated, NPs fill the void in caring for the poor and uninsured, as well as older adults. They successfully manage chronic illnesses, effectively preventing patient hospitalizations at the same rate as physicians (Kuo, Chen, Baillargeon, Raji, & Goodwin, 2015). Multiple studies have demonstrated that NPs provide quality care comparable with, if not better than physicians (Kippenbrock et al., 2019). Patient satisfaction scores have also been comparable to those of physicians (Naylor & Kurtaman, 2010) (Table 1).

Primary Care Providers by the Numbers

The Affordable Care Act (2010), which President Obama signed into law in 2010, provided access to healthcare for millions of uninsured Americans. With the number of medical students going into primary care residencies on the decline, a shortage of 52,000 primary care physicians is expected by 2025 (Fodeman & Factor, 2015). Conversely, the number of NPs is on the rise. According to AANP (2020), as of February 2020, there are over 290,000 licensed NPs in the United States (US). Almost 90% of NPs are certified in primary care and 69% actually provide primary care. The numbers keep growing with over 28,700 recent graduates in 2018 (AANP, 2020).

Almost 90% of NPs are certified in primary care and 69% actually provide primary care.In 2015, 1,965 medical students chose primary care residencies. The same year, 14,400 NPs graduated from primary care programs (Barnes, Aiken, & Villarruel, 2016). This contributed to an 18% decrease in primary care physician visits and a 129% increase in primary care NP visits (Cheney, 2018). NPs are filling the primary care role that physicians once dominated and they are addressing the crucial gap in the primary care healthcare workforce (See Table 1).

Post Pandemic Billing Policies

The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated how removal of practice restrictions can increase the care NPs can deliver, while maintaining quality.The independent role of the NP continues to evolve. The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated how removal of practice restrictions can increase the care NPs can deliver, while maintaining quality. As the number of states allowing full practice authority for NPs grows, barriers to practice need removal. Nurse-managed health centers and retail clinics, run primarily by NPs, confirm the impact that NPs can have in delivery of high quality, cost effective care (Hansen-Turton, Bailey, Torres, & Ritter, 2010) (See Table 1). Appropriate direct reimbursement for these services, independent of a relationship with a physician, is even more warranted in these types of situations where the rules of “incident to billing” cannot be followed.

MedPAC and Reimbursement Policy

Current Medicare reimbursement for NPs comes from the Balanced Budget Act (1997) (See Table 2). Nurse lobbying groups compromised on the NP reimbursement rate of 85% of the physician fee because the location restriction for NP care was removed. As the number of NPs continued to rise, removing the location barrier was a great feat (Apold, 2011). The MedPAC was also established by the Balanced Budget Act (1997). This group is an independent group of 17 individuals that advises Congress on issues related to Medicare. Two of the current members are nurses (MedPAC, 2021).

Current Medicare reimbursement for NPs comes from the Balanced Budget Act (1997)MedPAC meets frequently and issues two reports to Congress each year. In June 2002, they voted unanimously to increase CNM reimbursement from 65% to 85%. This put CNMs on par with the other NPs and PAs. When evaluating the 65% reimbursement, MedPAC looked at the services delivered by CNMs and compared them to those of NPs and PAs. It was determined that there was no justification as to why CNMs should be reimbursed less than NPs or PAs (MedPAC, 2002).

In the same 2002 session, MedPAC looked at the justification of the 85% rule. The main question was “Do physicians and NPPs produce the same product?” (MedPAC, 2002). Their conclusion was that the two groups actually produce different products, because NPPs tend to care for the less complex patients, and certain procedures could only be done by physicians (See Tables 1 and 2). Interestingly, they also reconsidered “incident to” billing and decided to continue reimbursing NPPs at 100% if they submitted the bill as “incident to” (MedPAC, 2002).

In June 2019, MedPAC again addressed payment policies for NPs and PAs. They concluded that the number of NPs and PAs has grown substantially and continues to grow. From 2010 – 2017, the number of NPs who billed Medicare increased by 151%. The number of Evaluation & Management (E/M) visits by NPs increased from 11 million to 31 million, while the number of visits billed by physicians decreased by 16%. As impressive as these numbers are, the actual numbers are higher because many NPs are still billing under “incident to,” and these visits are not reflected in the data. In fact, MedPAC estimates that about half of NPs billed “incident to” in 2016. (MedPAC, 2019a).

In June 2019, MedPAC again addressed payment policies for NPs and PAs. Because visits that are billed “incident to” are reimbursed at 100%, and visits billed under an NP provider number are billed at 85%, Medicare would save a substantial amount of money by eliminating “incident to “billing. MedPAC estimates a savings of $50 million to $250 million in the first year. Based on these numbers, MedPAC unanimously recommended to Congress in June 2019, to eliminate “incident to” billing for NPs and PAs (MedPAC, 2019a). Congress has not yet acted on their recommendation. This contrasts with their 2002 decision to continue “incident to” billing. Although there was no discussion at that time to increase the reimbursement from 85% to 100%, this could certainly be an opportunity for NPs to bring this issue back to the forefront.

Considerations for Post COVID-19 Policy Solutions

The Rural Health Clinic Services Act (1977) enabled NPs to bill Medicare directly, without a supervising physician. From this point, NPs could provide more independent care. Often that care is still provided to patients in underserved communities, where physician shortages have left the population without accessible care. Nurse-managed health centers and retail clinics that are run and managed by NPs are expanding.

Nurse-managed health centers and retail clinics that are run and managed by NPs are expanding.Barnes, Aiken and Villaruel (2016) reviewed over 40 years of studies that all support the quality and safety of NP care. These studies demonstrated outcomes comparable to, and sometimes better than, physicians. For example, preventive care, including cancer screenings, increased under the care of NPs. Hospitalization rate with NP care was comparable to that of physicians. Patient satisfaction scores for NPs were high, with millions of patients choosing NPs as their primary care provider.

CMS bases physician payment on a formula that includes relative value units (RVUs). RVUs consider not only clinician work for the service provided, but also includes overhead office expenses and professional liability insurance expenses. Adjustments are made for the geographic area (MedPAC, 2019b). CMS argues that a disparity exists between physician and NP payment because physicians have higher training cost, they are responsible for the overhead office cost, and they pay higher malpractice premiums. These are legitimate points. In fact, educational cost for NPs is about 20-25 % of physician training cost (AANP, 2013). However, with nurse managed clinics, the overhead cost may need to be re-examined (See Tables 1 and 2).

Increasing reimbursement for NPs from 85% to 100% would support more robust primary care.Increasing reimbursement for NPs from 85% to 100% would support more robust primary care. One can argue that it is because of the high training cost that physicians incur that they choose to practice in higher paying specialties. NPs have also increased their role in specialties. More than 89% of NPs are certified in primary care, yet 69% actually practice in primary care (AANP, 2020). NPs are generally paid higher salaries in specialties than in primary care. By increasing reimbursement for NPs to 100%, CMS can create a greater incentive for NPs to remain in the area for which they were trained, primary care practice. This becomes even more important if Congress chooses to accept MedPACs recommendation and eliminate “incident to” billing. MedPAC estimated that half of all primary care NPs are billing “incident to.” If that is eliminated, practices would lose 15% of reimbursement for those visits.

The number of states granting full practice authority to NPs is growing.NPs now have prescriptive authority in all 50 states. The number of states granting full practice authority to NPs is growing. The COVID-19 pandemic led many states to lift restrictions on NP practice. These events were instrumental in increasing primary care access by allowing NPs to practice to the full extent of their license. Increasing the reimbursement rate to 100% will support NPs in all these settings and most appropriately increase the healthcare workforce in the provision of primary care.

Action Steps to Move Forward

Call for 100% of Physician Payment Rate

Medicare should increase the reimbursement rate of NPs to 100% of the physician payment rate. Medicare should increase the reimbursement rate of NPs to 100% of the physician payment rate. With MedPAC as the organization tasked with advising Congress about best practices for Medicare, action steps to increase reimbursement need to focus on MedPAC buy-in that NPs” produce the same product” as physicians. The ideal way to see change occur is to provide the facts. In their June 2019 report, MedPAC acknowledged that care once provided by physicians is shifting toward NPs and PAs (MedPAC, 2019a). This is a start to establish the evidence that NPs can indeed “produce the same product” as physicians.

Call for Rigorous Evidence

Although MedPAC discussions acknowledged that numerous studies exist that have supported the quality, cost savings, and positive patient experience related to care that NPs provide, MedPAC (2019a) pointed out that few of these studies used a randomized design. Many were retrospective studies with limitations of potential bias and confounding issues. They also noted that many studies are outdated and questioned if the current education and training of NPs today is comparable to NPs trained previously (MedPAC, 2019a). Additional and more rigorous research is needed.

Nurse advocacy groups can use the MedPAC report to direct future research studies. These studies must further explore the effect that NPs have on healthcare today. Researchers need to investigate how full practice authority, and the removal of practice barriers due to the COVID-19 pandemic, have affected the level of care that NPs provide. Such studies can then be used to support further evolution of reimbursement policy, if NPs indeed produce an equal or better product than physicians. This is the key to equal reimbursement.

Summary

Evolution of practice since 2002 provides considerable rationale, discussed in this article, that lends support to the question by MedPAC, “do physicians and NPPs produce the same product?” (MedPAC, 2002). Now is the time for NPs to receive full reimbursement from Medicare. The 85% rule was instituted at a time when the work environment looked very different. With an increase in full practice authority states, and nurse-managed healthcare centers and retail clinics, many NPs practice independently.

The 85% rule was instituted at a time when the work environment looked very different.With the decrease in primary care physicians and the increase in NPs, full reimbursement can incentivize practice owners to hire NPs to fill the void. This change could also increase feasibility for NPs to operate their own practices from a financial standpoint. Most NPs are trained in primary care and often provide care to an underserved population. Studies have supported this NP care as cost-effective. Thus, NPs offer an ideal solution to the primary care provider shortage. Reimbursement parity will make it easier for NPs to meet the growing need for primary care providers.

Reimbursement parity will make it easier for NPs to meet the growing need for primary care providers.MedPAC has already supported an increase in reimbursement for CNMs in 2002 and as recently as 2019 reconsidered how Medicare reimburses NPs. The COVID-19 pandemic serendipitously led to the removal of many restrictions on NP practice, a positive change that needs to become permanent. This is the time for NPs to seize the opportunity to work with MedPAC to achieve full reimbursement for care provided.

Authors

Alycia Bischof, MSN, APRN, PNP-BC

Email: abischof@nursing.upenn.edu

Alycia Bischof is a lecturer at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing. She specializes in teaching graduate nursing students about reimbursement and coding in the primary care setting. She is a PNCB board certified, practicing pediatric nurse practitioner. She received a BSN and MSN from the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing. She is currently a DNP candidate at the University of Pennsylvania.

Sherry A. Greenberg, PhD, RN, GNP-BC, FGSA, FAANP, FAAN

Email: sherry.greenberg@shu.edu

Dr. Sherry Greenberg is an Associate Professor at Seton Hall University College of Nursing and a Courtesy-Appointed Associate Professor at New York University Rory Meyers College of Nursing. Dr. Greenberg is a nurse practitioner faculty consultant on the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Age-Friendly Health Systems initiative. Dr. Greenberg currently serves as President-Elect on the Board of Directors of the Gerontological Advanced Practice Nurses Association and as a member of the Jonas Scholars Alumni Council. She is a member of the Gerontology & Geriatrics Education Editorial Board and a peer reviewer for multiple journals. Dr. Greenberg is a Fellow in the American Academy of Nursing, American Association of Nurse Practitioners, Gerontological Society of America, and New York Academy of Medicine, as well as Distinguished Educator in Gerontological Nursing through the National Hartford Center of Gerontological Nursing Excellence. Dr. Greenberg earned Bachelor, Master, and PhD degrees in nursing from the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing and was a Jonas Nurse Leaders Scholar. Her research has focused on fear of falling among older adults and the relationship with the neighborhood-built environment. Dr. Greenberg has worked as a certified gerontological nurse practitioner in acute, long-term care, and outpatient primary care practices and has taught at undergraduate and graduate nursing levels.

References

American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP). (2013). Nurse practitioner cost effectiveness. AANP Positions and Papers. Retrieved from: https://www.aanp.org/advocacy/advocacy-resource/position-statements/position-statements

American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP). (2018, March 19). Number of nurse practitioners hits new record high. AANP News Feed. Retrieved from: https://www.aanp.org/news-feed/number-of-nurse-practitioners-hits-new-record-high

American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP). (2020). NP fact sheet. All About NPs. Retrieved from: https://www.aanp.org/about/all-about-nps/np-fact-sheet

American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP). (2021). State practice environment. State Advocacy. Retrieved from: https://www.aanp.org/advocacy/state/state-practice-environment

Apold, S. (2011). From the desk of the ACNP Health Policy Director. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 7(5), 356. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2011.03.013

Barnes, H., Aiken, L. H., & Villarruel, A. M. (2016). Quality and safety of nurse practitioner care: The case for full practice authority in Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania Nurse, 71(4), 12-15. Retrieved from: https://www.nursing.upenn.edu/live/profiles/15283-quality-and-safety-of-nurse-practitioner-care-the

Chapman, S. A., Wides, C. D., & Spetz, J. (2010). Payment regulations for advanced practice nurses: Implications for primary care. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice, 11(2), 89-98. doi: 10.1177%2F1527154410382458

Cheney, C. (2018, November 16). Primary care physician office visits drop by 18%. HealthLeaders. Retrieved from: https://www.healthleadersmedia.com/clinical-care/primary-care-physician-office-visits-drop-18

Edmunds, M. W. (2014). Editorial: Important NP issues. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 10(9), A15-A16. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2014.09.007

Fodeman, J., & Factor, P. (2015). Solutions to the primary care physician shortage. The American Journal of Medicine, 128(8), 800-801. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.02.023

Hansen-Turton, T., Bailey, D. N., Torres, N., & Ritter, A. (2010). Nurse-managed health centers. American Journal of Nursing, 110(9), 23-26. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000388257.41804.41

Kippenbrock, T., Emory, J., Lee, P., Odell, E., Buron, B., & Morrison, B. (2019). A national survey of nurse practitioners' patient satisfaction outcomes. Nursing Outlook, 67(6), 707–712. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2019.04.010

Kuo, Y. F., Chen, N. W., Baillargeon, J., Raji, M. A., & Goodwin, J. S. (2015). Potentially preventable hospitalizations in Medicare patients with diabetes: A comparison of primary care provided by nurse practitioners versus physicians. Medical Care, 53(9), 776–783. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000406

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). (2002). Report to the Congress: Medicare payment to Advanced Practice Nurses and Physician Assistants. Retrieved from: http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/jun02_NonPhysPay.pdf?sfvrsn=0

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). (2019a). Report to the Congress: Medicare and the Healthcare Delivery System. Retrieved from: http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/jun19_medpac_reporttocongress_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). (2019b). Physician and other health professional payment system. Payment Basics. Retrieved from: http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/payment-basics/medpac_payment_basics_19_physician_final_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). (2021). About MedPAC. MedPAC Home. Retrieved from http://www.medpac.gov/-about-medpac-

Naylor, M. D., & Kurtzman, E. T. (2010). The role of nurse practitioners in reinventing primary care. Health Affairs, 29(5), 893-899. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0440

Nickerson, G. (2014). Rural health clinics. National Rural Health Association Policy Brief. Retrieved from: https://www.ruralhealthweb.org/getattachment/Advocate/Policy-Documents/RHCApril20143-(1).pdf.aspx?lang=en-US

Rapsilber, L. (2019). Incident to billing in a value-based reimbursement world. The Nurse Practitioner, 44(2), 15-17. doi: 10.1097/01.npr.0000552680.76769.e5

Shay, D. F. (2015). Using Medicare" Incident-to" rules. Family Practice Management, 22(2), 15-17. Retrieved from: https://www.aafp.org/fpm/2015/0300/p15.html

Sullivan-Marx, E. M. (2008). Lessons learned from advanced practice nursing payment. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice, 9(2), 121-126. doi: 10.1177%2F1527154408318098

U. S. Congress. (1990). Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990, Pub. L. No. 101-508, 104 Stat. 143. Retrieved from: https://www.congress.gov/bill/101st-congress/house-bill/5835

U. S. Congress. (1977). Rural Health Clinic Services Act of 1977, Pub. L. No. 95-210. Retrieved from: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-91/pdf/STATUTE-91-Pg1485.pdf

U. S. Congress. (1997). Balanced Budget Act of 1997, Pub. L. No 105-33, Stat. 251. Retrieved from: https://www.congress.gov/bill/105th-congress/house-bill/2015

U. S. Congress. (2010). Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Pub. L. No. 111-148, 124 Stat. 119. Retrieved from: https://www.congress.gov/111/plaws/publ148/PLAW-111publ148.pdf

Zolot, J. (2020). COVID-19 brings changes to NP scope of practice. American Journal of Nursing, 120(8), 14. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000694516.02685.29