The public image of nurse professionalism is important. Attributes of a professional nurse, such as caring, attentive, empathetic, efficient, knowledgeable, competent, and approachable, or lack thereof, can contribute positively or negatively to the patient experience. Nurses at a hospital in central northeast Pennsylvania offer their story as they considered the impact of a wide variety of individual uniform and dress choices. This article describes an evidence based practice project and survey created to increase understanding of patient perceptions regarding the professional image of nurses in this facility. Exploring patient perception of nurse image provided insight into what patients view as important. A team approach included the voice of nurses at different levels in the process. Ultimately, this work informed a revision of the health system nursing dress code. The study team also reflects on challenges, next steps in the process, and offers recommendations based on their experiences.

Key words: Professionalism, nurse image, patient experience, patient perceptions, dress code, nursing uniforms, evidence-based practice, shared governance

...how a nurse appears can have a significant impact on how a patient perceives the nurse. The goal of healthcare is to provide the best possible outcomes and experiences for patients and families. To that end, registered nurses (RNs) strive for professionalism in all aspects of care and interaction. First impressions are often formed in an instant, so how a nurse appears can have a significant impact on how a patient perceives the nurse. A uniform serves as a reflection of how the public identifies the role of the wearer (Bates, 2010).

Although consistently identified as members of one of the most trusted professions (Riffkin, 2014), contemporary nurses still struggle with image. In the media, nursing is portrayed in various ways: from matronly in a white uniform with a cap to sensual and cute in a tight miniskirt (Kelly, Fealy, & Watson, 2012). In reality, the nurse uniform influences perceptions about nursing practice and thus contributes significantly to the overall image of a nurse (Wocial, Sego, Rager, Laubersheimer & Everett, 2014a).

Nursing uniforms have been a source of tension for well over a hundred years (Pearson, Baker, Walsh, & Fitzgerald, 2001). In the 19th century, Florence Nightingale promoted excellence by creating a vision that was intended to raise nursing to a respectable profession characterized by caring, compassion, and clinical competence. She established a standard uniform for nurses as part of her effort to professionalize nursing (Houweling, 2004). Although the definition of the image of nursing is complex and dynamic, over 80% of Americans continue to list nursing as the most trustworthy profession in every Gallup Poll since 2005 (Swift, 2013).

The image of nursing is comprised of many components that identify nursing as a healthcare profession. Cohen, Bartholomew, Swihart, and Tomajan (2014) noted research study findings in which nurses identified several actions that they felt shape patient perception of them, such as whether they introduce themselves to patients as the nurse, whether they call patients by their names, and the level of their professional appearance. Study results indicated that 90% of the nurses felt that how they dressed had a great impact on their image.

The uniforms that most RNs wear have changed significantly in the last 20 years. The uniforms that most RNs wear have changed significantly in the last 20 years. Prior generations of healthcare personnel, particularly nursing staff, were required to follow stringent dress codes and work attire policies. White uniforms and nursing caps have been replaced by colored scrubs that have cartoon or holiday print decorations. White polished nursing shoes have been replaced by multicolored sneakers and clogs (Dumont & Tagnesi, 2011). Forces external to healthcare, such as the media and online marketing, have promoted individual preference as the new expression of “teaming and unity,” resulting in this more informal attire.

Nurses at Geisinger Medical Center had concerns about the impact of a wide variety of individual uniform and dress choices noted in their facility. This article describes an evidence based practice project and survey created to increase understanding of patient perceptions regarding the professional image of nurses in this facility. Exploring patient perception of nurse image provided insight into what patients actually view as important. A team approach included the voice of nurses at different levels in the process. Ultimately, this work informed a revision of the health system nursing dress code. The article also includes reflections from the study team about challenges and next steps in the process, and offers recommendations based on their experiences.

Our Story

Feedback from patient rounds, interactions with family members, and colleagues at other Magnet® healthcare organizations indicated uncertainty about who nursing care providers were and how to identify different levels of nursing personnel. Geisinger Medical Center is a hospital in central northeast Pennsylvania. In 2014, nurse leaders identified the need to re-evaluate current dress code policies in light of mounting challenges related to lack of a consistent dress code and a perceived decline in the professional appearance of the nursing staff. Feedback from patient rounds, interactions with family members, and colleagues at other Magnet® healthcare organizations indicated uncertainty about who nursing care providers were and how to identify different levels of nursing personnel. Nurse leaders began to discuss the need for an evidence-based practice (EBP) project to determine patient perceptions of professional image of nurses in the inpatient and outpatient settings within Geisinger Medical Center (GMC).

At the same time, staff members had begun an online dialogue on our system intranet expressing concerns regarding the informal nature of the nursing staff attire, such as nurses wearing hoodies, leggings, fleece jackets, and t-shirts while working. Concurrently, nursing staff on one of the adult inpatient medical surgical units voiced concerns about variations in fellow staff members’ patterns of dress and appearance to unit leadership. Staff of all skill levels, many of whom had worked in healthcare/nursing for many years, began a dialogue about professional appearance as it related to peers who were wearing clothing that did not meet traditional uniform standards.

Some patient statements indicated that staff members appeared “ready for the gym” or dressed like they were “at the club,” not as professionals in a hospital. During this time, there was also discussions regarding patients’ perceptions of professional appearance related to not only attire, but other expressions of individuality, such as jewelry, piercings, and tattoos. Some patient statements indicated that staff members appeared “ready for the gym” or dressed like they were “at the club,” not as professionals in a hospital. Unit staff and leaders noted that patients and families often expressed that they could not differentiate the skill levels of staff members. Other staff contended that many patients and families who were in distress or crisis liked the distraction of conversations about staff tattoos; they then shared stories of their own body art, allowing for development of rapport in the patient-caregiver relationship.

Based on the staff’s many conversations about patients’ stories and opinions in terms of their own work life, professional appearance, and the patient experience, unit leadership identified a need to address these concerns by considering revisions to the dress code policy. The current policy described acceptable types of clothing and stipulations about tattoos, but was not based on actual patient perceptions of what elements of professional image translated to their perception of excellent care. Staff nurses and nurse managers decided to evaluate evidence on this topic to inform and update the policy to reflect an evidence-based standard.

Creating an EBP Project

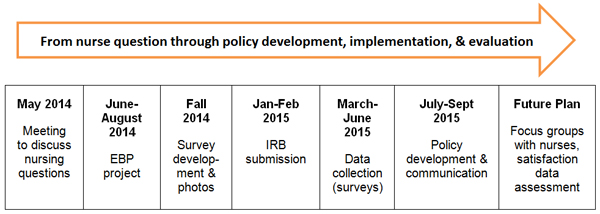

The aim of our project was to assess what patients perceive to be the most professional appearance, communications, and actions by a nurse. Nursing has a long and valued history of using research to impact practice, beginning with the earliest pioneer, Florence Nightingale (Nightingale, 1859). Evidence-based practice (EBP) is the conscientious and judicious use of current best evidence in conjunction with clinical nursing knowledge and patient values to guide healthcare decisions (Jennings & Loan, 2001). The process begins with a question, followed by an extensive review of the literature to evaluate what answers and discussion already exist. The aim of our project was to assess what patients perceive to be the most professional appearance, communications, and actions by a nurse. The goal was to use the findings to create an evidence-based dress code policy that would support the most professional image of nurses in our facility and hopefully contribute toward the best patient experience. This section will describe the project as it evolved. The figure below outlines the timeline of our work.

Figure. Timeline

Step 1: Review of the Literature

The Geisinger Medical Center uses the Johns Hopkins Model of EBP (Dearholt & Dang, 2012). Nurses refined their EBP question, met with nurses from the system Nursing Research and Evidence Based Practice Council, and began the review of the literature.

Photo images and patient preferences. The importance of professional image has been a focus within nursing for decades. Fogle & Reams (2014) wrote a brief historical perspective of nurses’ dress code. They concluded that consistency in nursing attire communicates professionalism and allows patients to identify nurses easily.

Windle, Halbert, Dumont, Tagnesi, and Johnson (2008), surveyed 430 patients at one hospital using a tool that included questions on ability to identify the nurse, professional image of the RN, and how patients prefer to see their nurse dressed. The tool included 12 photos of nurses in various dress and patients identified the photo they preferred. They rated nurses highly on image but had some difficulty identifying the nurse. Dumont and Tagnesi (2011) repeated the study with nurses wearing a large print RN on the identification badge; the ability to identify the nurse significantly improved. Also, most patients preferred that nurses use their first names and did not like to be called pet names, such as honey or sweetie.

Other studies (Albert, Wocial, Meyer, & Trochelman 2008; Kaser, Bugle, & Jackson, 2009) used the Nurse Image Scale (NIS) to assess patient perception of nurse professionalism, which also uses photos of nurse models and ratings related to characteristics such as confidence, competence, attentiveness, efficiency, caring, and professionalism. Some results of the studies were mixed. Patients did not agree that scrubs with cartoons or holiday decorations appeared less professional and some liked the same uniform concept but did not have a color preference (Windle et al., 2008). Others preferred colors or all white and age of the patient impacted results (Albert et al., 2008; Kaser et al., 2009). Dumont and Tagnesi (2011) found that most patients preferred different colors of uniforms rather than all white ones.

One conclusion of these studies is that dress is a very strong form of nonverbal communication. Pearce et al. (2014) used an online survey and focus groups for both patients and nurses. Patients said it was very important to be able to identify the RN, but only half said color and scrubs were the priority. Patients felt nurses should wear a uniform that allowed comfort and ease for job performance. One conclusion of these studies is that dress is a very strong form of nonverbal communication.

Studies that included body art. Hatfield et al. (2013); Clavelle, Goodwin, & Tivis (2013); and Pfeifer (2012) conducted studies using pictorial images of nurses, considering color of uniforms, tattoos, and body piercings. Patients felt RNs appeared professional and were easily identified by a standardized uniform style and color. They gave high scores for nursing image, appearance, and identification, with less support for color-coded uniforms. Patients regarded the nurses as professional with less focus on attire and more focus on how knowledgeable and confident the nurses appear, and how well they provide care. Patients cared that nurses were clean and neat, and that clothing fit properly and looked nice. Most patients felt the white board and large RN badges were important. An implication of these studies was to take the time to probe patient preferences before implementing a policy change.

Thomas et al. (2010) had patients, nurses, students, and faculty view 18 color photos and rate a nurse’s level of caring, skill, and knowledge based on how the nurse looks. Nurses wearing solid scrubs were rated significantly more skilled and knowledgeable than a nurse wearing print or t-shirt attire by all groups. All subjects rated the nurse with the most body art (e.g., piercings, visible tattoos) the least caring, skilled, and knowledgeable. Thomas et al.’s (2010) findings suggested that nurses wear a solid color uniform with limited visible body art. Pfeifer’s (2012) research demonstrated that gender did not affect results. Males with visible piercings were almost never deemed more professional, and women with piercings other than earlobe were viewed even less favorably than their counterparts without piercings.

Dress code policies. Some articles discussed challenges of changing dress code policies. Everett (2012) described the process of moving nurses in a health system to the same color uniform. Nurse and patient focus groups supported decisions about uniforms (e.g., each department wore a different color). Patients felt it was easy to identify the nurse. Wocial, Sego, Rager, Laubersheimer, and Everett (2014b) conducted additional nurse focus groups in the same health system, asking 10 questions about nursing image. Results showed it is not simply uniform color or style that influences the image of nurses. Nurses felt that a uniform must communicate well to patients and families who the nurse is. More than uniforms, it is nurse behaviors (e.g., compassion, approachability, good manners, service-oriented) that define the patient experience. Nurses should hold each other accountable and convey assurance to each other, patients, and families through actions. But, this assurance is significantly influenced by how the nurse presents her or himself – the overall appearance.

Mitchell, Koen, and Moore (2013) also discussed dress code challenges. They presented the issue of religious discrimination focusing on dress and appearance and some court cases that have provided guidance for employers.

...we concluded that it was best to assess the perception of patients served at the micro level. Our conclusions. Most studies about RN identification and uniforms were done within a single hospital or health system. Most were not randomized, some lacked comparison groups, and many failed to control for extraneous variables that could potentially influence outcomes (Windall, 2008). The results of most studies suggested patients prefer nurses who are identifiable and professional in appearance. After synthesizing the literature findings, we concluded that it was best to assess the perception of patients served at the micro level. As a result, we developed tools locally, but informed by our literature search, did not use large, national, randomized surveys. After sharing the results with Geisinger nurses and leadership, we decided to create a survey with questions and photos to capture patient opinions at Geisinger about nurse professionalism and attire.

Step 2: Survey Development and Research Process

Developing our survey. Nurse input, the review of the literature from the EBP project, patient input, and review of patient satisfaction comments informed the development of our survey. With permission, our survey was partially adapted from Dumont and Tagnesi’s (2011) study. The survey included three sections: demographics, questions (14), and photos (6). Demographic queries included gender, birth year, number of admissions as Geisinger inpatient, and number of visits to a Geisinger clinic. The questions and photos addressed concerns about image that may relate to the patient’s perception of his or her experiences.

Nurse input, the review of the literature from the EBP project, patient input, and review of patient satisfaction comments informed the development of our survey. Participants ranked each of the 14 questions on a Likert type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Questions inquired about verbal interactions, nurse appearance, and ability to identify caregivers. For example, one question asked if the nurse’s appearance made them feel confident that he or she had the ability to care for them. Other questions asked for opinions about whether nurses should wear t-shirts or multi-colored, patterned uniforms. Some questions asked participants if they prefer to be called Mr. or Mrs., or by their first names.

The six nurse photo pictures included the same male and female nurse models in each photo. Participants were asked to rank each photo on a Likert type scale from 1 (less professional) to 5 (more professional). In the survey, a professional nurse was defined as one who is caring, attentive, confident, reliable, empathetic, efficient, cooperative, knowledgeable, competent, and approachable (attributes noted in the literature review). One photo had nurses dressed in solid navy scrubs. Other nurses wore long sleeved t-shirts with tie-dyed arms and blue hospital scrub pants. One photo illustrated a layered look for the tops and hospital blue scrub bottoms. Other photos included nurses with solid scrubs with a tighter fit; holiday scrubs; and solid tops and bottoms in different colors. In addition to the varying uniform scrubs, in two photos the photography team added jewelry and tattoos since these were also discussed in the literature. We used six different copies of the survey, with photos in a different order in each set of surveys, to achieve random presentation.

Table. Study Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

|

INCLUSION CRITERIA |

EXCLUSION CRITERIA |

|

|

Members of the study team talked with Operations Managers on each of the adult inpatient medical-surgical units and the adult outpatient clinics to explain the study. Study team members visited potential participants on adult medical-surgical units and adult outpatient clinics at GMC. The study team member talked with the inpatient charge nurse prior to gathering data, to identify patients who met the eligibility criteria. This prevented the team from approaching patients who did not wish to be disturbed or did not meet appropriate criteria. All potential participants were asked if they had previously completed the survey.

Data collection process. The survey took 10 to 15 minutes to complete. Study team members gave verbal, scripted directions to participants and asked if they were willing to complete the survey. Then they gave each participant on an information letter explaining the survey and an invitation to participate. Finally, the study team member gave the letter and survey to patients and instructed them to place it in an envelope and seal it when finished. The study team member returned within an hour to pick up the sealed envelope.

Step 3: Summary of Survey Findings

Setting, population, and sample. The survey was distributed to Geisinger Medical Center adult patients in the inpatient and outpatient clinics. After approval from the institutional review board (IRB), the nurse study team recruited a convenience sample of 200 outpatients and 200 inpatients. Specific inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in the Table.

Our study addressed the patient experience indirectly, based on both patient perceptions that we have noted, and those in the literature. The purpose was to inform dress code decisions at the system level, and hopefully improve the patient experience by addressing known feedback. The scope of this work was not meant to capture every intricacy of the patient experience or explore specific correlations.

We used descriptive statistics to analyze 400 completed participant surveys to describe what patients perceived as the most professional dress appearance and the most professional comments and actions by the nurse. Participants (57%) felt they could usually identify the registered nurse but it was often difficult to differentiate between the RN, licensed practical nurse (LPN), and the nursing assistant (NA). Most (79%) agreed that nurses were dressed in a manner that helped them feel confident about their ability. Participants (80%) liked that “RN” was in large print on the name badge and felt that white boards in the room that identified the nurse’s name were beneficial. Respondents (74%) felt that nurses look professional when they are all dressed in the same uniform, but varied in opinion on whether solid color (59%) or patterned (64%) was best. All felt strongly that t-shirts with sayings and pictures should not be permitted. Participants (63%) preferred to be called by Mr. or Mrs. and then by their first name after the initial introduction. All agreed that no one liked to be called by the endearing terms honey or sweetheart. An area of concern was that patients (55%) were not able to identify all people that entered their room and did not know the department in which each person worked.

The photo identified as most professional was the solid navy scrubs (95% of participants). Participants (85%) ranked the photo with layered tops as less professional. Participants (85%) strongly disliked the photo with tie dye t-shirts and hospital scrub pants. Holiday scrubs had a mixed ranking (41% supported; 59% did not).

Upon collection of the surveys, many participants expressed desire for an area to write comments. After analysis, the study team summarized the results and presented them to hospital nursing councils and leadership teams.

Step 4: Policy Change Process

Council members felt that a more standard dress code policy for all employees (not just nursing) would improve the overall professional appearance of staff and provide consistency across departments. Council input. During annual review, the Nursing Retention and Communication Council (NRCC) was asked to update the dress code policy, if the council felt changes were indicated. Council members determined a need to observe staff to determine current adherence to the existing policy. Members observed all staff, including those employees outside of nursing, in the cafeteria setting. Inconsistencies in adherence to the dress code policy, not only in nursing but across all departments, were noted during this observation. Council members felt that a more standard dress code policy for all employees (not just nursing) would improve the overall professional appearance of staff and provide consistency across departments. The NRCC communicated concerns with the human resources (HR) department; HR indicated that each department set their own dress code.

Given this information, the NRCC members revised the nursing dress code policy to include several changes regarding neatness of appearance, excessive jewelry, and permitted tattoos to be exposed unless inappropriate (showing violence, drugs, sex, alcohol, or profanity). The revised dress code policy was approved in August 2015, after vetting by hospital-wide shared governance councils. These councils included Nursing Services Quality Performance Improvement Council, Nursing Research, Inpatient Manager Council, Outpatient Manager Council, and Professional Practice Council.

... an effort to find all current versions of dress code polices for the health system identified approximately 70 discrete dress code policies. System changes. Last year, an effort to find all current versions of dress code policies for the health system identified approximately 70 discrete dress code policies. Leaders at GMC recognized that the presence of so many different policies was confusing and lacked any consistent uniformity across disciplines, departments, and campuses. These policies were collated into one concise document which was vetted and approved through the shared governance councils.

The Geisinger Medical Center nursing department is currently working to standardize dress color for RN staff. In a joint press release, Chief Patient Experience Officers Susan M. Robel R.N. and Dr. Greg Burke (2015) stated, “The first impression we give patients and visitors is determined not only by our tone and expertise, but also by our appearance and demeanor” (Sylvester, 2015, p. 2). They continued, “Recent studies have shown that patients associate professional attire with honesty, knowledge, and high quality care” (Sylvester, 2015, p. 2). This press release clearly conveyed to Geisinger employees, as well as our patients and families, the importance of professional attire.

Effective January 1, 2016, all RNs will transition to pewter gray and white scrub uniforms. The new uniform tops and scrub jackets will be embroidered with the Geisinger logo and “Registered Nurse.” In addition, nurses will be able to have certification initials embroidered on the left sleeve. A system task force has been assembled to address specific nursing practice specialties, such as Pediatrics and Maternal Health, to standardize what nurses in these areas will be permitted to wear.

Our Challenges

As the process has evolved, we have noted challenges related to team tasks, communication, and cost. This section briefly describes past and present challenges and our solutions, if solved.

Team challenges. It was easy to get volunteers from hospital nursing leadership to be on the study team. Once assembled, the challenge became the ability to coordinate very busy schedules in order to formulate our thoughts and ideas for protocol development. The only convenient time to meet was during the lunch hour over the course of several weeks.

A major consideration was to determine whether to conduct the study at the hospital versus the system level. We then had to go back to system nursing leadership to obtain their input. Once the protocol was finalized and IRB application completed, it took two months to finalize IRB approval.

Another time related challenge for the study team was administering the surveys on inpatient units and outpatient clinics. Prior to data collection, we needed to educate key leaders for these units and clinics about the purpose of study and convey that the team would be present to administer surveys. Once data analysis was completed, it took a couple of months to disseminate results to key stake holders, hospital-wide shared governance councils, and bedside nursing staff.

Because the new dress code is a major change for nurses’ appearance, as well as a change in culture, staff had many questions and concerns. Communication challenges. Because the decision to change the RN dress code affected so many nurses across several campuses, consistent communication was imperative. Corporate Communications released a system-wide email to notify staff about details of the change and provided a press release to local newspapers to inform the public. Because the new dress code is a major change for nurses’ appearance, as well as a change in culture, staff had many questions and concerns. To provide effective, consistent communication about this change, we created talking points that allowed nurse leaders to engage staff affected by the policy changes.

In our organization, only RNs are transitioning to a standardized uniform at the present. LPNs and NAs will transition at a future date. These staff members are naturally anxious about the color choice for their uniforms and transition timeline for that change. Another key consideration is to anticipate questions and concerns of the staff and provide timely information.

Cost challenges. To create a uniform appearance for the pewter gray and white uniforms, the system selected a single vendor to offer uniforms for purchase. The vendor came to campus on several dates and times convenient for nursing staff. Recognizing the financial impact of requiring purchase of new uniforms, nursing leadership provided each RN a $150 uniform allowance toward the first purchase of the required uniforms and a 25% discount on those purchases. Following the vendor events, an online ordering system will continue to offer discounted prices to staff purchasing additional uniforms.

Next Steps

Guidelines for exceptions will be decided by direct care nursing staff members who serve on nursing councils. The next steps to fulfill our goal of providing the best possible patient experience involves the tedious work of operationalizing this significant change for our nursing team members by working with the vendor described above. Simultaneously, we will work within our shared governance support structure to seek input from nursing councils regarding exceptions to the uniform standards. For example, staff members are asking if there are certain days that they may wear holiday-themed scrubs, or hospital-sponsored t-shirts. Guidelines for exceptions will be decided by direct care nursing staff members who serve on nursing councils. Councils will utilize the findings from the evidence based practice project and patient research results to make these decisions.

A goal of this process for the coming year will be to analyze patient experience data retrieved through routine collection (i.e. random surveys currently sent to patients), particularly pertaining to patients’ perceptions of nursing staff members treating patients courteously, working together, and overall perceptions of care. Once our changes are completely operationalized, we could specifically query about the professional image of nursing staff in future patient questionnaires. This could be an opportunity to explain to patients how their feedback was used to change policy.

Another next step of this project includes plans to examine whether a dress code policy change has affected nurses’ beliefs, perceptions, and thoughts on their own level of professionalism. In the year following implementation, our goal is to facilitate RN focus groups for subjective information sharing and discussions about how the change has impacted work life, job enjoyment, professional demeanor, and team relationships. Our aims will be to examine if direct care staff feel a higher level of engagement and if they enjoy a stronger sense of partnership in their work life, and to seek feedback about other ways that uniform standardization may have changed their work life.

Our ultimate goal is to support a superb patient experience by decreasing variation in appearance and increasing focus on quality of care. Implementation of the revised hospital dress code that standardizes nursing uniforms will be the first steps in a fundamental culture shift for our healthcare workforce at Geisinger Medical Center. These changes impact upon the physical, mental, moral, and socioeconomic dynamics of the workplace and the employees therein. Our ultimate goal is to support a superb patient experience by decreasing variation in appearance and increasing focus on quality of care. As we move towards implementation, this emphasis in professional image represents the paradigm that will serve as the platform for further examination of the perceptions and experiences of our patients.

Recommendations and Conclusion

The study team identified a number of tips and recommendations throughout the survey process and through discussions with patients and families. Patients stated that they would have appreciated an area within the survey for comments. This was further supported by the number of surveys with comments and ideas written all over the margins of the survey tool. Therefore, we recommend including a section for patient comments.

Although patients were given an invitation to participate and an informational letter that explained the survey, we found that patients were more likely to consent if the purpose of the survey was explained by the study team member. In our interactions with patients, when we introduced ourselves as Geisinger nurses and emphasized that we were asking their input to help us improve our patients’ experiences, most patients were willing to complete the survey.

In the outpatient setting, we found that it was important to assure patients in the pre-appointment waiting room that if they were called for their appointment, we would wait. Thus they did not feel rushed or feel compelled to refuse to participate for fear they might be interrupted for the appointment. It was helpful to tell them they could finish the survey after their appointment, place it in the sealed envelope, give it to reception staff, and we would return for it later in the day.

As the survey tool was developed, it was important to include staff from some of our Nursing Councils. As noted previously, the NRCC had spent months revising the dress policy and members actively participated in the development of the questions that were used in the survey. We also felt it was important to assess various levels of nursing leadership support to confirm willingness to consider the results as impetus to move ahead with changes in the dress code policy.

We strongly feel that the standardization of nurse uniforms in our health system will have a positive impact on the patient experience by promoting a consistent professional image and helping patients to identify RN caregivers. One area that we felt we could have done differently was a more formal approach to communication with inpatient and outpatient nurses about the time frame for the survey and more discussion about survey questions. We suggest an email to inpatient and outpatient managers that they could forward to each staff person, informing them of details. We also made the decision to have the members of the EBP study group complete data collection, because we felt they were non-biased and would not influence or impact patient responses.

We recommend considering a variety of approaches to conducting the survey, including surveying nurses and patients, or just nurses rather than just surveying patients. All of those options are discussed in the literature.

In conclusion, this EBP project to increase our understanding of patient perceptions regarding the professional image of nurses in this facility has successfully resulted in an evidence-based policy change for our nursing dress code. We strongly feel that the standardization of nurse uniforms in our health system will have a positive impact on the patient experience by promoting a consistent professional image and helping patients to identify RN caregivers. Our future plans to implement the standardized dress code to a wider level of providers and to continue to evaluate the potential impact on patient experience will inform additional policy revisions as needed. This article has provided a detailed description of the process, as well as challenges and recommendations, in the hope that our efforts may be useful to other facilities addressing concerns related to professional image and the patient experience.

Authors

Margaret Mary West, PhD, RN, CNE

Email: mmwest@geisinger.edu

Margaret Mary is the Director of System Nursing Research for the Geisinger Health System. M. M. earned her Bachelor of Science degree in Nursing from Bloomsburg University in Bloomsburg, PA, her Master of Science in Nursing from Misericordia University in Dallas, PA, and her PhD in Nursing Research and Education from Widener University in Chester, PA. Her career began in critical care nursing at Geisinger Medical Center, followed with chapters in education and administration with Penn State University in State College, PA and Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, PA, until her present position with Geisinger. Nursing research and education have been the common threads throughout her career.

Debra Wantz Bucher, DNP, RN, CCNS, NEA-BC

Email: dwantz@geisinger.edu

Debra is currently the Operations Manager of 42-bed Level I Trauma, a Gold Beacon designated adult intensive care unit at Geisinger Medical Center. She earned a Bachelor of Science and a Master of Science degree in Nursing from Bloomsburg University in Bloomsburg, PA and a Doctor of Nursing Practice from Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, PA. She is certified both as a critical care clinical nurse specialist through AACN and a Nurse Executive, Advanced through ANCC. Deb has worked at Geisinger almost 30 years including as a staff nurse and Team Coordinator in cardiac intensive care, a Clinical Nurse Specialist in the Advanced Heart Failure Program and as an Operations Manager in Nursing Education. She has been the Primary Investigator on several nursing research studies and a Co-Investigator on several industry-sponsored pharmaceutical and device trials.

Patricia A. Campbell, MSN, RN

Email: pancampbell@geisinger.edu

Patricia is the Director of Outpatient Nursing and the Coordinator of Student Nurse Affiliations at Geisinger Medical Center. She is a graduate of the Geisinger School of Nursing, earned a Bachelor of Science degree in Nursing at Bloomsburg University in Bloomsburg, PA and a Master of Science in Nursing Administration from the University of Pittsburgh. Pat has been employed at Geisinger for 32 years, including as a staff nurse in critical care, a Clinical Nurse Specialist in the renal transplant program and as an Operations Manager in the outpatient clinics. She was also previously employed at Yale New Haven Hospital and Lehigh Valley Hospital. Pat is chair of the Geisinger Facilities Safety Committee and participates on the Hospital Quality Improvement Committee and as the advisor to various nursing councils.

Greta Rosler, MSN, RN, NEA-BC

Email: gerosler@geisinger.edu

Greta is an Operations Manager at Geisinger Medical Center and leads frontline teams on 3 medical surgical units and a wound ostomy team. In addition, she advises the hospital’s Professional Practice Council, with a daily focus on staff engagement and patient experience. Greta obtained her Bachelor of Science degree in Nursing from Bloomsburg University in Bloomsburg, PA, her MSN with a concentration in Leadership and Management from Walden University, Minneapolis, MN, and is a certified Nurse Executive, Advanced. She has worked across the inpatient and outpatient continuum of care, including in critical care settings, outpatient surgery, rehabilitation, long term acute care, and most recently, as a nurse leader in an academic medical center.

Dawn S. Troutman, BSN, RN, CCRN, NE-BC

Email: dstroutman@geisinger.edu

Dawn is an Operations Manager for three Special Care Units at Geisinger Medical Center. Dawn has her Bachelor of Science degree in Nursing from Bloomsburg University in Bloomsberg, PA. She began her nursing career as a Medical Surgical nurse at Geisinger, then transferred to the Special Care Unit where she enjoyed working as a staff nurse, then Team Leader. Dawn has been a nurse at Geisinger Medical Center for over 23 years. She is also the lead manager for the Nursing Retention and Communication Committee. This council was responsible for reviewing the dress code policy for nursing.

Crystal Muthler, MHA, BSN, RN, NEA-BC

Email: cmuthler@geisinger.edu

Crystal is the Chief Nursing Officer, Vice President of Nursing at Geisinger Medical Center. She received her Bachelor of Science degree in Nursing from Bloomsburg University in Bloomsburg, PA and her Master in Health Services Administration from Marywood University in Scranton, PA. She holds a licensure/certification from the Pennsylvania State Board of Nursing and the ANCC-Nurse Executive Advanced – Board Certified. Crystal started her journey with Geisinger 26 years ago as a staff nurse on a medical/surgical telemetry unit, worked as an Administrative Supervisor, Operations Manager, Clinical Director of the Surgical Suite and Associate Vice President of Nursing Services prior to her current role.

References

Albert, N., Wocial, L., Meyer, J., & Trochelman, K. (2008). Impact of nurses on patient and family perceptions of nurse professionalism, Applied Nursing Research, 21(4), 181-190. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2007.04.008.

Bates, C. (2010). Looking closely: Material and visual approaches to the nurse’s uniform. Nursing History Review, 18, 167-188.

Clavelle, J., Goodwin, M. & Tivis, L. (2013). Nursing professional attire, The Journal of Nursing Administration, 43(3), 172-177. doi:10.1097/NNA.0b013e318283dc78

Cohen, S., Bartholomew, K., Swihart, D., & Tomajan, K, (2014). The image of nursing: Your ethical and professional role. HCPro – White Paper, 1-31

Dearholt, S. & Dang, D. (2012). Johns Hopkins nursing evidence-based practice: Model and guidelines. Indianapolis, IN.: Sigma Theta Tau.

Dumont, C., & Tagnesi, K. (2011). Nursing image: What research tells us about patients’ opinions. Nursing 2011, 1, 9-11.

Everett, L.Q. (2012). On changing RN uniform color: May the bridges I burn light the way. Nurse Leader, 10(6), 34-35. doi: 10.1016/j.mnl.2012.09.005

Fogle, C. & Reams, P. (2014). Taking a uniform approach to nursing attire. Nursing, 44(6), 50-54. doi: 10.1097/01.NURSE.0000444535.96822.3b.

Hatfield, L.A., Pearce, M., Del Guidice, M., Cassidy, C., Samoyan, J., & Polomano, R.C. (2013). The professional appearance of registered nurses: An integrated review of peer refereed students. Journal of Nursing Administration, 43(2), 108-122. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e31827f2260.

Houweling, L. (2004). Image, function, and style: A history of the nursing uniform. American Journal of Nursing, 104(4), 40-48.

Jennings, B. & Loan, L. (2011). Misconceptions among nurses about evidence-based practice. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 33(2), 121-127.

Kaser, M., Bugle, L., & Jackson, E. (2009). Dress code debate. Nursing Management, 40(1), 33-38.

Kelly, J., Fealy, G., & Watson, R. (2012). The image of you: Constructing nursing identities in YouTube. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68(8), 1804-1813. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05872.x.

Mitchell, M., Koen, C., & Moore, T. (2013). Dress code and appearance policies: Challenges under federal legislation, Part 1: Title VII of the civil rights act and religion. The Health Care Manager, 32(4), 294. doi: 10.1097/HCM.0b013e3182a9d878.

Nightingale, F. (1859). Notes on nursing. London: Harrison & Sons.

Pearce, M., Guidice, M., Kinzey, A., Knight, G., Cassidy, C., Farrell, K., & Hatfield, L. (2014). Color coding nurse uniforms. Nursing Management, 45(2), 14-20. doi: 10.1097/01.NUMA.0000442644.93700.58.

Pearson, A., Baker, H., Walsh, K., & Fitzgerald, M. (2001). Contemporary nurses’ uniforms – history and tradition. Journal of Nursing Management, 9, 147-152.

Pfeifer, G. (2012). Attitudes toward piercings and tattoos. American Journal of Nursing, 112(5), 15. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000414303.32050.99.

Riffkin, R. (2014, December 18). Americans rate nurses highest on honesty, ethical standards. Gallup. Retrieved from: http://www.gallup.com/poll/180260/americans-rate-nurses-highest-honesty-ethical-standards.aspx

Robel, S.M., & Burke, G. (2015, August 21). Press release. Geisinger Medical Center [internal document, used with permission].

Swift, A. (2013, December 13). Honesty and ethics relating of clergy slides to new low. Gallup. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/166298/honesty-ethics-rating-clergy-slides-new-low.aspx

Sylvester, J. (August 21, 2015). Geisinger scrubs individuality. The Daily Item. Retrieved from http://www.dailyitem.com/news/geisinger-scrubs-individuality/article_2bcdc55c-479d-11e5-b605-ef22e170ca82.html

Thomas, C.M., Ehret, A., Ellis, B., Colon-Shoop, S., Linton, J., & Metz, S. (2010). Perception of nurse caring, skills, and knowledge based on appearance. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 49(11), 489-497. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e3181f88b48.

Windle, L., Halbert, K., Dumnet, C., Tagnesi, K. & Johnson, K. (2014). An evidence-based approach to creating a new dress code. American Nurse Today, 3(1), 1-2.

Wocial, L., Sego, K., Rager, C.. Laubersheimer, S., & Everett, L. (2014a). Image is more than a uniform. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 44(5), 298-302.

Wocial, L., Sego, K., Rager, C., Laubersheimer, S., & Everett, L. (2014b). Transforming the image of nursing: The evidence for assurance. The Health Care Manager, 33(4), 297-303. doi: 10.1097/HCM.0000000000000028.