As nurses, we seek to better understand how to gain nursing ‘wisdom’ and apply this wisdom in our daily practice. Yet the concept and experience of ‘wisdom in nursing practice’ has not been well defined. This article addresses wisdom-in-action for nursing practice. We briefly describe nursing theory, review the wisdom literature as presented in various disciplines, and identify characteristics of wisdom by analyzing four models of wisdom from other disciplines. We also present the ten antecedents of wisdom and the ten characteristics of wisdom identified in our analysis of the wisdom literature, discuss and summarize these antecedents, and conclude that understanding these ten antecedents and the ten characteristics of wisdom-in-action can both help nurses demonstrate wisdom as they provide nursing care and teach new nurses the process of becoming wise in nursing practice.

Key Words: wisdom, knowledge, informatics, concept analysis, antecedents of wisdom, characteristics of wisdom, wisdom-in-action

Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge?

Thomas Stearns Eliot (1969, p. 147)

Few could imagine the technological advances that would occur after T.S. Eliot wrote this poetic line in 1934, relating wisdom to knowledge and suggesting a distinct relationship between the concepts. In 2008, the American Nurses Association (ANA) released the revised Nursing Informatics: Scope and Standards of Practice adding the concept of wisdom to the accepted framework of data, information, and knowledge concepts in nursing informatics. This expanded Data, Information, Knowledge, Wisdom (DIKW) Framework is widely accepted by the international, nursing informatics (NI) community as a foundational model for the field of nursing (Nelson, 2002).

Wisdom is defined in the Merriam-Webster Dictionary (2014) as (a) knowledge gained through life experiences, (b) the innate ability to understand things that others cannot understand, and (c) judgment or good sense. In the NI Scope and Standards of Practice, wisdom is defined as “…the appropriate use of knowledge to manage and solve human problems. It is knowing when and how to apply knowledge to deal with complex problems or specific human needs” (ANA, 2008, p. 5). Although the concept of wisdom has been added to the NI Scope and Standards of Practice, the concept and its applicability to nursing have not been well defined beyond the field of nursing informatics (Matney, Brewster, Sward, Cloyes, & Staggers, 2011). Because nurses have a desire to apply wisdom within their practice and nurse informaticists need to understand how to support the use of wisdom in practice (see discussion below), a clearer understanding of the concept is needed. This article describes a deliberate study to identify characteristics of nursing wisdom by examining four theories in other disciplines.

Nursing Theory

Theory is used in all aspects of nursing care and assists the practicing nurse in organizing, understanding and analyzing patient data. Nursing theory facilitates the development of nursing knowledge and provides principles to support nursing practice. Theory shapes practice and provides a method for expressing key ideas regarding the essence of nursing practice (Walker & Avant, 2011). Nursing theory is developed from groups of concepts and describes their interrelationships, thus presenting a systematic view of nursing-related events. The purpose of theory is to describe, explain, predict, and /or prescribe (Chinn & Kramer, 2011; Reed & Shearer, 2007; Risjord, 2009; Walker & Avant, 2011). Theory is used in all aspects of nursing care and assists the practicing nurse in organizing, understanding and analyzing patient data. Essentially, theory provides a systematic, consistent way of thinking about nursing care to guide the decision-making process. Theory-based, clinical practice occurs when nurses intentionally structure their practice around a particular theory to guide them in their care of the patient.

One of the greatest contributions grand theories... provide for nursing is the differentiation between nursing practice and the practice of medicine. Different levels of nursing theory exist; these levels include metatheory, grand theory, and mid-range theories. Metatheories focus on theory about theory. These theories develop through asking philosophical and methodological questions to form a nursing foundation. Grand theories give a broad perspective for the purpose and structure of nursing practice (Peterson & Bredow, 2008; Walker & Avant, 2011). One of the greatest contributions grand theories, largely developed between the 1960s and the 1980s, provide for nursing is the differentiation between nursing practice and the practice of medicine. In contrast, mid-range nursing theories contain a related set of ideas and variables, are narrower in scope, and are testable (Smith & Liehr, 2008; Walker & Avant, 2011). They offer the specificity needed for usefulness in research and practice, usually focusing on one specific topic or area of care and often beginning with a concept analysis and the development of a larger conceptual model (often called a construct).

Review of the Wisdom Literature

Wisdom is an abstract ideal, an end-point or characteristic, something applied in, yet separate from practice. Today, we have a large body of literature about wisdom, although much of it does not relate to wisdom in nursing practice. Wisdom is an abstract ideal, an end-point or characteristic, something applied in, yet separate from practice. The focus of this article is to further nursing’s clinical (practice) wisdom. To support this exploration, definitions of wisdom from the early (classic) philosophy and psychology literature, and the alignment of these definitions with nursing, as well as definitions from the nursing literature are presented.

Philosophy

Classical philosophers began defining wisdom as early as 400 B.C. Plato wrote that wisdom is the knowledge about the good between all that exists (Truglio-Londrigan, 2002) while according to Aristotle, wisdom is knowledge of the first causes and principles of things (Rice, 1958). Aristotle differentiated wisdom into five states of mind: episteme or scientific knowledge; theoretikes or theoretical knowledge devoted to truth; techne or technical skill; phronesis or practical wisdom, which enables ethical action that contributes to the common good; and sophia which is concerned with truth towards a practical end (McKie et al., 2012). All five of these wisdom states could define the art and science of nursing practice. The nursing profession is built upon scientific knowledge (episteme) and nursing practice is grounded with theory (theoretikes) (ANA, 2004). Nurses must understand and stay abreast of current technology (techne). One of the nursing standards of practice is ethics; hence, nurses integrate ethics (phronesis) into all areas of their practice. Finally, the art of nursing practice is based on a framework of caring (sophia).

Psychology

Personal wisdom comes into play after experienced nurses reflect on their own practice, and learn from their experiences, thereby increasing their personal knowledge. There are two types of wisdom described in the psychology literature, namely general and personal wisdom (Staudinger & Glück, 2011). General wisdom is directed toward other individuals from a third-person perspective. It is a personal trait manifested by caring for others. In contrast, personal wisdom is individual, focused on advice and judgment that is based on insight gained from experience (Mickler & Staudinger, 2008). Personal wisdom is about one's own life and problems seen from a first-person perspective. These are both important to understand because nursing pertains to both general and personal wisdom. Initially, general wisdom is used when caring for the wellbeing of others during practice (Staudinger & Glück, 2011). Afterwards, learning from the caring experience can be applied personally. Personal wisdom comes into play after experienced nurses reflect on their own practice, and learn from their experiences, thereby increasing their personal knowledge.

Extensive research concerning wisdom is available in psychology (Staudinger & Glück, 2011). Bluck and Glück (2004) qualitatively analyzed autobiographical narratives from individuals of all ages concerning times where they felt they said or did something wise. Results demonstrated that all age groups were able to change negative life experiences into positive ones when wisdom was used. Bluck and Glück defined wisdom as an adaptive form of judgment that involves how one thinks. In a second qualitative study, Glück and Baltes (2006) asked subjects to describe wise people. Resulting themes included morality, integrity, overcoming risk or adversity, searching for insight, and striving toward individual improvement.

Wisdom is assumed to be intrinsically associated with age and experience... [but] age is not necessarily a factor in being a wise nurse. Wisdom is assumed to be intrinsically associated with age and experience. Although older people have more experiences, age is not the only characteristic associated with wisdom. Pasupathi (2001) has posited that those who are “open to new experiences, are creative, who think about the how and why of an event rather than simply whether it is good or bad, who demonstrate more social intelligence, or who are oriented towards personal growth display higher levels of wisdom-related knowledge and judgment” (p. 403). This is important for nursing because it means that age is not necessarily a factor in being a wise nurse.

Sternberg (2007) and his team hypothesized that the key leadership components of wisdom are intelligence, creativity, and knowledge, as well as being able to use these characteristics to make good decisions. His team presented difficult life problem vignettes along with possible solutions to study participants. The participants rated the solutions. Then, their solutions were compared against ratings from psychological experts. Findings showed that people with general wisdom demonstrate this wisdom regarding the stories, but that they may, or may not, necessarily apply that same wisdom themselves (Staudinger & Glück, 2011).

The findings from psychology illustrate that important wisdom-character precursors include morality, integrity, creativity, intelligence, knowledge and insight, as well as concepts used during the application of wisdom, such as judgment and thinking of others. All of these concepts align with the practice of nursing.

Nursing

Few authors have explored or attempted to define wisdom in a nursing context. Benner (2000) wrote that nursing wisdom is based on clinical judgment and a thinking-in-action approach encompassing intuition, emotions, and senses. Benner and colleagues (1999) described clinically wise nurses as both proficient and expert. Matney, et al. (2011) described wisdom as the application of experience, intelligence, creativity, and knowledge, mediated by values, toward the achievement of a common good. These definitions link wisdom to performance, or nursing practice, leading one to recognize that wisdom must be tied to actions using skills and knowledge.

Haggerty and Grace (2008) evaluated the psychology and philosophical wisdom literature to determine the key components of clinical wisdom. They identified the following three themes: “balancing and providing for the good of another and the common good, the use of intellect and affect in problem solving, and the demonstration of experience-based tacit knowing in problematic situations” (p. 235). Christley and colleagues (2012) completed a concept analysis of ‘Practical Wisdom’ describing three antecedents (also called precursors) and three attributes of practical wisdom along with their implications for nursing practice. The three antecedents were experience and reflection, along with ‘care, compassion and empathy.’ The three wisdom attributes were experiential knowing; judgment and balance; and action.

Two concepts from the field of philosophy, praxis and phronesis, are associated with wisdom in nursing. Two concepts from the field of philosophy, praxis and phronesis, are associated with wisdom in nursing. Praxis is defined as the act of putting theory into practice (Rolfe, 2006). Praxis is developed from moral, experiential, and practice-related situations and changes over time with increased experience (Connor, 2004). Litchfield (1999) illustrated a nursing-praxis framework, merging theory, practice, and research.

Phronesis is defined in the nursing literature as practical wisdom requiring the context of the situation to be considered before action is taken (Connor, 2004; Flaming, 2001; James, Andershed, Gustavsson, & Ternestedt, 2010; Leathard & Cook, 2009). Phronesis is indicative of morality in that nurses need to be ready to determine the most appropriate response in particular circumstances (Chen, 2011). It is paired with praxis by relating intellectual virtues to practice (Newham, Curzio, Carr, & Terry, 2014).

Characteristics of wisdom found in praxis and phronesis (e.g., putting theory into both practice and morality) can be applied to nursing practice; yet, how they are applied is not clear. A clearer understanding of the concept of wisdom is needed to understand how knowledge is translated or ‘actioned’ into wisdom during practice. Clinical nursing is a process requiring a practice-based theory of wisdom rooted in action. Understanding wisdom from a nursing context will leverage the ability of both practicing nurses and nursing informaticists as they facilitate the development and use of wisdom. This article focuses on identifying wisdom concepts that pertain to clinical nursing and that are derived from wisdom theories in other disciplines.

As authors, we made three assumptions pertinent to the identification of wisdom characteristics and the development of a theory for nursing. First, wisdom is defined in other disciplines. Therefore, these existing theories of wisdom likely contain characteristics useful for wisdom in clinical nursing even though these theories from other disciplines have not yet been collected into a single whole. Second, nurses provide care for patients in clinical situations using wisdom. Third, nurses use both general and personal wisdom as described above.

Identification of Wisdom Characteristics

The process of derivation as defined by Walker and Avant (2011) was used in the identification of wisdom characteristics. Derivation implies that the concepts are obtained from another source. The method entails examining existing models or theories; selecting a core model, or models, from which to create a new theory; and specifying how existing models are adapted. This derivation process included three steps: (a) identification of potential theories that may contribute to or overlap with nursing wisdom; (b) selection of the theories from which the characteristics could be derived; and (c) analysis of the characteristics of the parent theories needed for the new nursing theory. We followed this process to produce a list of wisdom antecedents and characteristics that describe and can support wisdom in nursing practice

Multiple wisdom models from other disciplines were evaluated and analyzed using formal theory analysis for possible derivation (Walker & Avant, 2011). We used the following four models or theories for theory derivation: The DIKW framework from the computer science and nursing informatics discipline; the Berlin Wisdom Paradigm (BWP) and the MORE Wisdom Model from the psychology discipline; and finally the model of wisdom development (MWD) from the education discipline. These models were chosen because they focus on knowledge as the core of wisdom, a central component in the application of wisdom to any actions. Each is described below.

Data, Information, Knowledge, Wisdom (DIKW) Framework

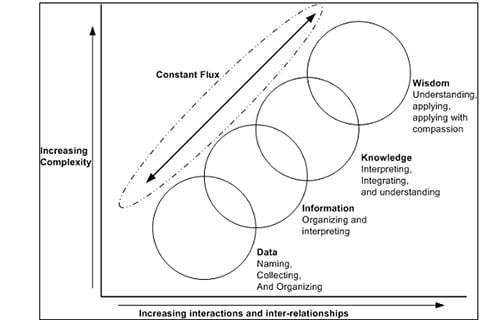

The initial model evaluated was the DIKW framework that originated in computer and information sciences, particularly in knowledge management (Blum, 1986). The DIK portion of the framework was first discussed in nursing in Graves and Corcoran’s (1989) work; the DIKW framework was first described for nursing informatics by Nelson (2002) and adopted by the ANA in 2008 (ANA, 2008; Schleyer & Beaudry, 2009).

Figure reprinted with permission from Ramona Nelson, Copyright © 2008, Ramona Nelson Consulting. All rights reserved.

Wisdom is using knowledge correctly to handle or explain human problems. The components consist of four overlapping concepts: data, information, knowledge, and wisdom (Figure 1). Data are symbols that represent properties of objects, events, and their environments that alone have little meaning. Information is data given structure. Knowledge is derived by discovering patterns and relationships between types of information (Nelson, 2002). Wisdom is using knowledge correctly to handle or explain human problems. The ANA describes wisdom as the ability to evaluate the information and knowledge within the context of caring, and use judgment to make care decisions (ANA, 2008; Matney, et al., 2011).

The Berlin Wisdom Paradigm (BWP)

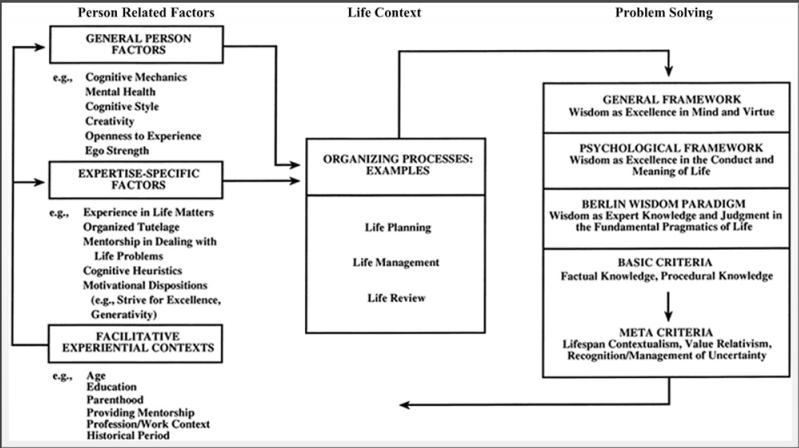

The BWP was developed at the Max Planck Institute to provide direction towards investigation of wisdom-related knowledge systems and judgment processes (Baltes & Staudinger, 1993; Smith, Dixon, & Baltes, 1989). They defined wisdom as “a cognitive and motivational metaheuristic (pragmatic) that organizes and orchestrates knowledge toward human excellence in mind and virtue, both individually and collectively” (Baltes & Staudinger, 2000a, p. 132). The fundamental pragmatics in life refers to deep insight and sound judgment regarding the human condition and the ways of planning, managing and understanding life (Staudinger & Glück, 2011). Metaheuristics are high level strategies that organize lower level rules within individuals to assist in planning, managing and evaluating life issues.

Figure 2. Berlin Wisdom Paradigm

Figure reprinted with permission from Baltes, P. B., & Staudinger, U. M. (2000a). Wisdom. A metaheuristic (pragmatic) to orchestrate mind and virtue toward excellence. The American Psychologist, 55(1), 122-136.

The BWP (Figure 2) is composed of three different sections: Person Related Factors, Life Context, and Problem Solving (Baltes & Staudinger, 2000a). The sections include wisdom antecedent factor (precursors) and process concepts. The first section, ‘Person Related Factors,’ contains three categories considered antecedents to wisdom development. The second section of the framework is ‘Life Context’ and is defined as wisdom applied to actual life. Wisdom involves using good judgment, insight, emotional regulation, and empathy and is found in all areas of life including family interactions, writing, and personal relations. The third section portrays qualitative criteria for solving problems. Five expertise-specific categories are deemed sequential for developing expertise: experience in life matters, organized tutelage, mentorship in dealing with life problems, cognitive heuristics, and motivational dispositions (Baltes & Staudinger, 2000b). This theory led us to investigate the MORE Wisdom Model.

The MORE Wisdom Model

The acronym MORE represents the following concepts: Mastery, Openness, Reflection, and Emotional Regulation or Expertise (Figure 3). It was conceptually derived from the BWP (Figure 2) (Glück, 2010; Glück & Bluck, 2013) with the goal of developing a specific framework for understanding why and how some people cumulatively develop wisdom while others do not. The authors' first study was conducted using autobiographical narratives of people who thought they were wise. The second was a qualitative study of people nominated as wise; open interview questions were used in this study.

Figure reprinted with permission from the developer Judith Glück, PhD.

The first concept, sense of ‘Mastery,’ is the belief that any of life’s challenges can be dealt with, but also the awareness that not everything can be controlled. Challenges are managed head-on or through adaptation, and individuals do not feel victimized when events are beyond their control, giving individuals a sense of mastery.

The second concept is ‘Openness.’ People must have an interest in and be open to experiences and ideas to develop knowledge and use it wisely. High levels of openness help individuals seek out wisdom-fostering situations.

The third concept is a ‘Reflective Attitude.’ Wise individuals are reflective and motivated to think deeply. They step back and examine the situation to better understand the context and seriously examine their own past behavior to gain meaning and set direction. Individuals reflect on experiences and learn from them. Once knowledge is gained from experience and reflection, it can be applied in future situations.

Wise individuals are calm and self-controlled. The fourth and final concept is ‘Emotional Regulation,’ or control of emotions and the ability to be sensitive to other’s emotions. Wise individuals are calm and self-controlled. They perceive their emotions accurately and manage them appropriately in both positive and negative situations.

These positive and negative situations involve life experiences and serve as means for fostering wisdom development. The arrows (relationships) illustrate that life challenges lead to learning through a reciprocal relationship with the four characteristics.

Model of Wisdom Development (MWD)

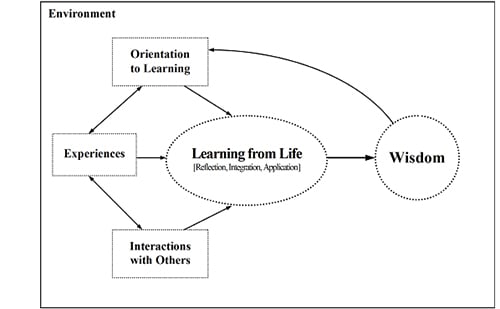

Brown, an educator, developed the Model of Wisdom Development (MWD) (2004). The central component of the MWD (Figure 4) is Learning from Life. This component includes concepts of reflection, integration, and application. Individuals must take information in, and then ponder, analyze, process, and integrate it into their conscious and unconscious actions. Once that is achieved, learning occurs, and the new knowledge can be used and applied. If it is not applied, the knowledge obtained does not result in growth or change.

Three conditions, all considered circumstances that affect the development of wisdom, are linked to the ‘Learning from Life’ core component. These conditions include: (a) orientation to learning, (b) experiences, and (c) interactions with others. Orientation to learning describes how a person approaches specific knowledge-gaining experiences and consists of motivation and a desire to learn. Experiences result in knowledge acquisition. Interaction with others requires a genuine caring and compassion for others, and a willingness to give of oneself to be of influence for the common good.

Figure 4. Model of Wisdom Development

Figure reprinted with permission (Brown, 2004)

Understanding of others is a true understanding of, and interest about others at the individual, social, and cultural levels. The final circle in the model, symbolizing the goal, is wisdom. Brown (2004) states that wisdom is comprised of six interrelating characteristics: self-knowledge, understanding of others, judgment, life knowledge, life skills, and willingness to learn. Self-knowledge is a consciousness of your own values, morals, ethics, talents and abilities pertaining to both personal and professional life. To have self-knowledge a person must have a clear understanding of themselves. Understanding of others is a true understanding of, and interest about others at the individual, social, and cultural levels. Judgment is the ability to take in information and apply it to a person’s life (i.e., the ability to assess and analyze a situation, and to make a sound decision). Life knowledge is a person’s reservoir of knowledge obtained from books and life experiences including common sense, understanding, and an appreciation of life. Life skills are characterized by individual competence in life matters. Finally, willingness to learn requires an admission of not knowing everything (humility), the understanding of our current level of knowledge, and the desire to know more.

Derived Nursing Wisdom Antecedents and Characteristics

The table below, developed by the first author, illustrates identified antecedents and characteristics of wisdom. Relationships between the concepts are beyond the scope of this article, but readers can begin to see that a possible theory of wisdom for nursing can be created from the derived concepts.

Table. Derived Antecedents and Characteristics

|

Wisdom Antecedents and Characteristics |

DIKW |

BWP |

MORE |

MWD |

Needs Nursing Definition |

||

|

Wisdom Antecedents/Precursors |

|||||||

|

Data |

x |

|

|

|

|

||

|

Information |

x |

|

|

|

x |

||

|

Age |

x |

x |

|

|

|

||

|

Education |

|

x |

|

x |

x |

||

|

Social Interaction |

|

x |

|

|

|

||

|

Values, Relativism, and Tolerance |

|

x |

|

x |

x |

||

|

Cognition |

|

x |

|

|

x |

||

|

Openness to Learning |

|

x |

x |

x |

|

||

|

Mentors/Role Models |

|

x |

|

|

x |

||

|

Life Experiences |

|

|

|

x |

x |

||

|

Wisdom Characteristics |

|

||||||

|

Rich Factual Knowledge |

|

x |

|

|

x |

||

|

Rich Procedural Knowledge |

|

x |

|

|

x |

||

|

Lifespan Contextualism |

|

x |

|

x |

x |

||

|

Knowledge Mastery |

x |

|

x |

x |

x |

||

|

Stressful Situation or Management of Uncertainty |

|

x |

|

|

x |

||

|

Judgment |

|

|

x |

x |

x |

||

|

Decision |

|

|

|

x |

x |

||

|

Application |

|

|

|

x |

x |

||

|

Reflection |

|

|

x |

x |

x |

||

|

Learning |

|

|

|

x |

x |

||

Discussion and Summary

Knowledge was present in every model as a precursor to wisdom. The evaluation of the four derivation models resulted in the initial set of antecedents and characteristics as well as the following insights. Knowledge was present in every model as a precursor to wisdom. Other precursors included data, information, age, education, values, cognition, openness to learning, mentors, and life experiences. The BWP and MORE models both described the wisdom development process as the application of knowledge in a stressful situation or when dealing with uncertainty. Also important were openness to along with actual learning. Finally, reflection was required for learning. From informatics we came to appreciate how data is structured into information, and rules (logic) are applied to this information to derive knowledge.

The two types of wisdom described in psychology, general and personal, apply to clinical nursing as well. The implications are that the antecedents and characteristics may be different for the two types of wisdom. General wisdom is evident when giving caring and compassionate practice focused on individual patients and their loved ones. It is having the desire to give them excellent care and using professional expertise when making clinical judgments. General wisdom may also be present in the moral and ethical decision-making process. Personal wisdom is evident after the situation has occurred, when individuals take time to reflect, study, learn, and ponder their own values and morals and gain understanding. The characteristic of knowledge overlaps both general and personal wisdom. Expertise used in caring is knowledge used in practice for another person and is considered general wisdom. Personal wisdom develops as the nurse gains knowledge after reflecting on a situation.

Wisdom in nursing practice is a complex phenomenon not completely understood through a single list of antecedents and characteristics. Wisdom in nursing practice is a complex phenomenon not completely understood through a single list of antecedents and characteristics. The characteristics of wisdom described above were taken from theories of other disciplines. The question that remains unanswered is, “How are wisdom antecedents and characteristics defined for nursing?” Thus, in a subsequent step, the nursing literature will be further evaluated to define the characteristics within a nursing context and to determine if additional concepts are needed.

Conclusion

In this article, we specifically presented the characteristics of wisdom used in clinical nursing by outlining an analysis of wisdom models from other disciplines, and identifying fundamental characteristics and antecedents for the concept of wisdom. Four models of wisdom were examined in an effort to determine applicable characteristics and antecedents. We identified ten potential characteristics and ten potential antecedents to wisdom. A clearer understanding of wisdom in nursing practice could allow nurses both to teach the process of becoming wise and to work toward achieving wisdom in their own practice.

Authors

Susan A. Matney, PhD, RN-C, FAAN

Email: samatney@mmm.com

Susan Matney is a Medical Informaticist with the 3M Health Information Systems, Healthcare Data Dictionary (HDD) Team. She has more than 15 years of experience in Informatics and 30 years of experience in nursing. In 2002, Susan took the terminology ‘Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC)’ to the American Nurses Association to be recognized as a terminology for use by nursing. She a Fellow of the American Academy of Nursing, and represents nursing at national/international conferences and other organizations, including Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine – Clinical Terminology (SNOMED-CT), Health Level 7 (HL7), LOINC, and the Federal Health Information Model Terminology (FHIM) team. Ms. Matney received her BSN degree from the University of Phoenix, Salt Lake City, UT; and her MSN degree from the University of Utah. Susan is an adjunct faculty member and a doctoral candidate at the University of Utah College Of Nursing in Salt Lake City, UT. Her dissertation is focusing on the development of a Theory of Wisdom-in-Action for Clinical Nursing.

Kay Avant, PhD, RN, FNI, FAAN

Email: avantk@uthscsa.edu

Dr. Avant, the Roger L. and Laura D. Zeller Distinguished Professor of Nursing at the University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, Texas, received her BSN degree from Texas Christian University in Fort Worth, Texas, her MSN degree from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and her PhD degree from Texas Woman’s University in Denton, Texas. She is best known for her classic publication, Strategies for Theory Construction in Nursing coauthored with Dr. Lorraine Walker. Dr. Avant is also an expert in nursing informatics and the development of electronic patient records. She is a past President of NANDA-International (The North American Nursing Diagnosis Association), a member of HL7 (the international standards organization for the interfacing of clinical data), a Fellow of the American Academy of Nursing, a Fellow of NANDA International, and a member of Sigma Theta Tau International. Her areas of clinical expertise include maternal/newborn interaction and parenting stress. Her scholarship has focused primarily in the area of clinical terminologies and theory development. Dr. Avant has had two Fulbright Professorships, one in Oslo, Norway, and one in Chiang Mai and Bangkok, Thailand. She continues to travel extensively as an international consultant.

Nancy Staggers, PhD, RN, FAAN

Email: nancystaggers@sisna.com

Dr. Staggers has an extensive health informatics background in both academe and operational information technology (IT) settings. She has been an IT executive for enterprise-wide electronic health record (EHR) projects. During her Army career, she led enterprise EHR installations for the Department of Defense. Her expertise is in the usability of clinical products. Her research program centers on usability of clinical IT products, handoffs, and informatics competencies. Her textbook on health informatics, co-authored with Dr. Nelson, was awarded textbook of the year for information and technology by the American Journal of Nursing. She is currently a health informatics consultant and an Adjunct Professor at the University of Utah College of Nursing and Biomedical Informatics, Salt Lake City, Utah. Dr. Staggers received her BSN degree from the School of Nursing, University of Wyoming, Laramie, and her MSN and PhD degrees from the School of Nursing, University of Maryland, Baltimore.

Truglio-Londrigan, M. (2002). An analysis of wisdom: An experience in nursing practice. The Journal of the New York State Nurses' Association, 33Walker, L. O., & Avant, K. C. (2011). Strategies for theory construction in nursing (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

References

American Nurses Association (ANA). (2004). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice. Silver Spring, MD: nursesbooks.org.

ANA. (2008). Nursing informatics: Scope and standards of practice. Silver Spring, MD: nursesbooks.org.

Baltes, P. B., & Staudinger, U. M. (1993). The search for a psychology of wisdom. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 2(3), 75-81.

Baltes, P. B., & Staudinger, U. M. (2000a). Wisdom. A metaheuristic (pragmatic) to orchestrate mind and virtue toward excellence. The American Psychologist, 55(1), 122-136.

Baltes, P. B., & Staudinger, U. M. (2000b). Wisdom. American Psychologist, 55(1), 122.

Benner, P. (2000). The wisdom of our practice. American Journal of Nursing, 100(10), 99-105.

Benner, P., Hooper-Hyriakidid, P., & Stannard, D. (1999). Clinical wisdom and interventions in critical care: A thinking-in-action approach. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders.

Bluck, S., & Glück, J. (2004). Making things better and learning a lesson: Experiencing wisdom across the lifespan. Journal of Personality, 72(3), 543-572.

Blum, B. (1986). Clinical information systems. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Brown, S. C. (2004). Learning across the campus: How college facilitates the development of wisdom. Journal of College Student Development, 45(2), 134-148.

Chen, R. P. (2011). Moral imagination in simulation-based communication skills training. Nursing ethics, 18(1), 102-111. doi: 10.1177/0969733010386163

Chinn, P. L., & Kramer, M. K. (2011). Integrated theory and knowledge development in nursing (Eighth ed.). St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby.

Christley, Y., McMillan, L., McCallum, L., & O’Neill, A. (2012). Practical wisdom in nursing practice: A concept analysis. Retrieved from https://www.rcn.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/445816/Research2012Mo15.pdf

Connor, M. J. (2004). The practical discourse in philosophy and nursing: An exploration of linkages and shifts in the evolution of praxis. Nursing Philosophy, 5(1), 54-66.

Eliot, T. (1969). The complete poems and plays of T.S. Eliot. London: Faber and Faber.

Flaming, D. (2001). Using phronesis instead of 'research-based practice' as the guiding light for nursing practice. Nursing Philosophy, 2(3), 251-258.

Glück, J. (2010). There is not bitterness when she looks back: Wisdom as a developmental opposite of embitterment. Embitterment: Societal, Psychological, and Clinical Perspectives (pp. 70-82). Vienna/New York: Springer Verlag.

Glück, J., & Baltes, P. B. (2006). Using the concept of wisdom to enhance the expression of wisdom knowledge: Not the philosopher's dream but differential effects of developmental preparedness. Psychology and Aging, 21(4), 679-690.

Glück, J., & Bluck, S. (2013). More wisdom: A developmental theory of personal wisdom: From contemplative traditions to neuroscience. In N. Ferrari & N. Weststrate (Eds.), The Scientific Study of Personal Wisdom (pp. 75-98). New York, NY: Springer.

Graves, J., & Corcoran, S. (1989). The study of nursing informatics. Image: Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 21(4), 227-231.

Haggerty, L. A., & Grace, P. (2008). Clinical wisdom: The essential foundation of “good” nursing care. Journal of Professional Nursing, 24(4), 235-240.

James, I., Andershed, B., Gustavsson, B., & Ternestedt, B. M. (2010). Knowledge constructions in nursing practice: Understanding and integrating different forms of knowledge. Qualitative Health Research, 20(11), 1500-1518. doi:10.1177/1049732310374042

Leathard, H. L., & Cook, M. J. (2009). Learning for holistic care: Addressing practical wisdom (phronesis) and the spiritual sphere. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65(6), 1318-1327.

Litchfield, M. (1999). Practice wisdom. ANS. Advances in Nursing Science, 22(2), 62-73.

Matney, S. A., Avant, K., & Staggers, N. (2013). The construct of wisdom in action for clinical nursing©. Paper presented at the American Nursing Informatics Association, San Antonio, TX.

Matney, S. A., Brewster, P. J., Sward, K. A., Cloyes, K. G., & Staggers, N. (2011). Philosophical approaches to the nursing informatics data-information-knowledge-wisdom framework. Advances in Nursing Science, 34(1), 6-18.

McKie, A., Baguley, F., Guthrie, C., Jackson, C., Kirkpatrick, P., Laing, A., ... Wimpenny, P. (2012). Exploring clinical wisdom in nursing education. Nursing Ethics, 19(2), 252-267. doi:10.1177/0969733011416841

Merriam-Webster. (2014). Retrieved from http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/wisdom

Mickler, C., & Staudinger, U. M. (2008). Personal wisdom: Validation and age-related differences of a performance measure. Psychology and Aging, 23(4), 787-799.

Nelson, R. (2002). Major theories supporting health care informatics. In S. Englebardt & R. Nelson (Eds.), Health Care Informatics: An Interdisciplinary Approach (pp. 3-27). St. Louis, MO: Mosby.

Newham, R., Curzio, J., Carr, G., & Terry, L. (2014). Contemporary nursing wisdom in the UK and ethical knowing: Difficulties in conceptualising the ethics of nursing. Nursing Philosophy, 15(1), 50-56. doi:10.1111/jnup.12028

Peterson, S. J., & Bredow, T. S. (2008). Middle range theories: Application to nursing research. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Reed, P. G., & Shearer, N. C. (2007). Perspectives on Nursing Theory (Fifth ed.): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Rice, E. F. (1958). The renaissance idea of wisdom. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Risjord, M. W. (2009). Nursing knowledge: Science, practice, and philosophy. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Rolfe, G. (2006). Nursing praxis and the science of the unique. Nursing Science Quarterly, 19(1), 39-43.

Schleyer, R., & Beaudry, S. (2009). Data to wisdom: Informatics in telephone triage nursing practice. AACN Viewpoint, 31(5), 1-13.

Smith, J., Dixon, R. A., & Baltes, P. B. (1989). Expertise in life planning: A new research approach to investigating aspects of wisdom. In M. L. Commons, J. D. Sinnott, F. A. Richards, & C. Armon (Eds.), Beyond formal operations II (Vol. 1, pp. 307–331). New York: Praeger.

Smith, M. J., & Liehr, P. R. (2008). Middle range theory for nursing. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company.

Staudinger, U. M., & Glück, J. (2011). Psychological wisdom research: Commonalities and differences in a growing field. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 215-241. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.121208.131659

Sternberg, R. J. (2007). A systems model of leadership: WICS. The American Psychologist, 62(1), 34-42; discussion 43-37.

Truglio-Londrigan, M. (2002). An analysis of wisdom: An experience in nursing practice. The Journal of the New York State Nurses' Association, 33Walker, L. O., & Avant, K. C. (2011). Strategies for theory construction in nursing (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.