The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted health inequities for people with intellectual and developmental disability (PWIDD). It was also the stimulus for an international group of nurse researchers with shared expertise and experience to create a Global IDD Nursing Collaboratory. A collaboratory is a networked environment or “center without walls” where interaction oriented to common research areas occur without regard to physical location. The overarching goal of this Global Nursing Collaboratory is to assure the highest quality of life for PWIDD across the lifespan. Applying their unique skills and expertise, nurses working across health and social contexts are often the bridge over the healthcare gaps encountered by PWIDD. This paper describes the potential practice, education, and research contributions nurses can make to reduce health inequities experienced by PWIDD. We will examine how we talk about disability, the impact of the current COVID 19 crisis, and our educational systems which in some countries leave nurses and other health professionals ill prepared to meet the unique needs of this population We will describe the context, access issues, and health service organizations for and with PWIDD across countries to equip nurses with basic knowledge of health care for PWIDD and energize meaningful improvement in delivery of this care. Importantly, we offer action steps for all nurses toward reducing stigma and health inequities related to living with an intellectual and developmental disability (IDD).

Key Words: Intellectual Disability, Developmental Disability, Learning Disability

...nurses need understanding and sensitivity to the unique needs of all people, including people with intellectual and developmental disabilities To provide holistic, person-centered care throughout the lifespan and in all settings, nurses need understanding and sensitivity to the unique needs of all people, including people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (PWIDD). With nearly 1 to 3% of the world population, or about 200 million people, living with an intellectual and developmental disability (IDD) nurses can expect to encounter PWIDD in any healthcare setting (Special Olympics, 2022). The health outcomes for PWIDD during the COVID-19 pandemic were devastating in terms of morbidity and mortality (Henderson et al., 2022; Landes et al., 2020; Turk et al., 2020) and demonstrated the need for nurses to have knowledge and confidence while providing care for this at-risk and vulnerable population.

The overarching goal of the Global IDD Nursing Collaboratory is to promote the highest quality of life for PWIDD across the lifespan. The global nature of these poor outcomes prompted international collaboration as a Global IDD Nursing Collaboratory to address longstanding entrenched inequities, which were exposed and exacerbated by the pandemic. A collaboratory is a networked environment or “center without walls” where interaction oriented to common research areas occur without regard to physical location (Wulf, 1989, p. 19). The overarching goal of the Global IDD Nursing Collaboratory is to promote the highest quality of life for PWIDD across the lifespan. In this article, we discuss common issues that contribute to health inequities for PWIDD, as identified by our collaboratory, including how we talk about disability; the impact of the current COVID 19 crisis; educational preparation (or lack thereof) for nurses related to meeting needs of PWIDD; and the context, access issues, and health service organization for and with PWIDD across countries. With the aim to equip and energize nurses with knowledge to promote equitable care, this article details specific actions for nurses to promote and improve the health and well-being of PWIDD.

Understanding Terminology of IDD

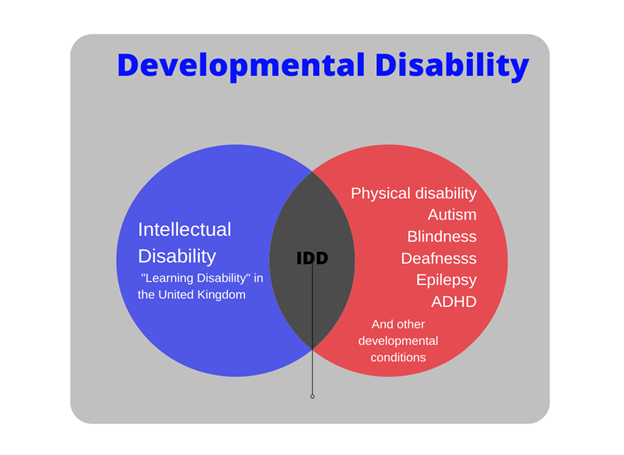

Many terms are used, often interchangeably, to describe conditions commonly associated with IDD. Many terms are used, often interchangeably, to describe conditions commonly associated with IDD. As the broadest conceptualization, "developmental disability" is defined as a chronic cognitive or physical condition (or both) that begins during the developmental period, is diagnosed before adulthood, and likely continues throughout the lifespan (CDC, 2022a). The age constituting adulthood varies by country/region but is generally recognized as between age 18 and 22 (AAIDD, 2022). Examples of developmental disabilities include hearing loss, vision impairment, cerebral palsy, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, intellectual disability, learning disability, and autism spectrum disorder.

Intellectual disability involves significant limitations in intellectual functioning...Intellectual disability involves significant limitations in intellectual functioning, meaning that people with intellectual disability have reduced ability to comprehend new or complex information, and solve problems. Intellectual functioning as measured on intelligence quotient (IQ) testing with scores less than 70 or up to 75 in some reports are characteristic (AAIDD, 2022). Challenges in two or more adaptive behavior areas must also be present, including conceptual skills such as telling time or managing money; social skills such as interpersonal skills and social problem solving; and functional skills such as activities of daily living and occupational skills (AAIDD, 2022). Because adaptive skills impact day-to-day living, PWIDD need support and varying types of assistance with activities of daily living. Of note, the term "intellectual disability" replaced its predecessor, "mental retardation," a term long considered disrespectful, offensive, and even abusive.

It is important to note that IDD can affect anyone from any ethnic or socio-economic background.Globally, intellectual disability is the recognized term. However, in the United Kingdom (UK; including England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland), “learning disability” is preferred. This can be confusing as in many parts of the world, the term "learning disability" is defined as discrepancies in learning outcomes in the absence of intellectual impairment (American Speech Language Hearing Association [ASHA], 1991). It is important to note that IDD can affect anyone from any ethnic or socio-economic background. The most common causes of intellectual disability include Down syndrome, Fragile X syndrome, and fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (CDC, 2022b). Intellectual disability also co-occurs in nearly a third of people with autism spectrum disorder (CDC, 2022c). Due to frequent overlap between intellectual disability and other developmental disabilities, the abbreviation IDD is commonly used. Because of the need to emphasize that people with IDD are people first and not objects of being intellectually disabled, in this article, we will use the acronym PWIDD to refer to a person or people who have IDD. See Figure 1 for a visual framework of common IDD terms.

Figure 1. Visual Representation of IDD Terminology

Note. IDD = intellectual and developmental disabilities

Impact of COVID 19 on PWIDD

Exacerbation of Health Inequities. The coronavirus pandemic highlighted health inequities for PWIDD, including higher risk of severe outcomes from COVID-19 infection and age-related differences. Studies from the United States (US) and UK revealed that PWIDD face greater risks of COVID-19 mortality, and at earlier ages, than the general population (Gleason et al., 2021; Henderson et al., 2022; Landes et al., 2020; Turk et al., 2020). The pandemic negatively impacted the ability of PWIDD to access needed healthcare and daily support services (Gleason et al., 2021). Further, while inpatient mortality in PWIDD was elevated compared to patients without IDD, they were less likely to be transferred to the intensive care unit (Gleason et al., 2021). This may be partly attributed to systemic bias toward PWIDD because of a perceived lower quality of life.

The pandemic negatively impacted the ability of PWIDD to access needed healthcare and daily support servicesBased on reports of denial of tests, treatments, ventilators, and pressure to reduce length of stay and life sustaining measures among multiple states in the US (Shapiro, 2020), the U.S. Office for Civil Rights (2020) prohibited discrimination and released a bulletin on civil rights laws that apply during the COVID-19 emergency. Fundamental principles of this bulletin emphasized non-discrimination in the treatment of persons with disabilities during medical emergencies, as they possess the same dignity and worth as everyone else.

Global Collaboration to Improve Outcomes. Early in the pandemic (i.e., from April 6-20, 2020), and as part of an American team of developmental disability (DD) nurse researchers, we surveyed 556 DD nurses nationwide, asking about challenges they were experiencing because of the pandemic (Desroches et al., 2021a). Findings from this study, which included a lack of preparedness on the part of the healthcare staff and system to meet the needs of PWIDD (Desroches et al., 2021a), drew the attention of colleagues in Canada. This led to the idea to expand our study internationally (Desroches et al., 2022) and sparked interest in forming a global collaborative of DD nurses.

The Global IDD Nursing Collaboratory mentioned earlier was built on informal networking, prior associations through scientific research meetings and the rise in telecommunication platforms such as Zoom. These factors assisted this evolution to address both disparities for PWIDD and associated pandemic related concerns during the global COVID shutdown. This international team of IDD nurse researchers from Australia, Canada, England, Ireland, New Zealand, Wales, and the United States is committed to address emerging concerns about healthcare needs of PWIDD. In the studies by Desroches et al., (2021a; 2021b) we identified the need for all nurses to be knowledgeable and competent in the effort to meet unique challenges of PWIDD, especially with their heightened vulnerability during the global public health crisis.

Context, Access, and Service Delivery

The paradigm of care and support for PWIDD has changed dramatically in the past 50 to 70 years. Historical Context. To meaningfully influence present day health outcomes, today’s nurses need to understand the historical social context surrounding care and treatment of PWIDD. The paradigm of care and support for PWIDD has changed dramatically in the past 50 to 70 years. In the late 19th and early 20th century, PWIDD, if not living with family, primarily resided in institutions, often called "schools," where they were meant to learn skills for an eventual, successful integration into community life (Nehring, 2001). Over time, however, and for most of the 20th century, the prevailing attitude was that PWIDD should be segregated away from society in these institutions for life, as a means to protect society and limit them from procreating and further burdening society. Care during this time was primarily custodial, and focused on medical treatment (Nehring, 2001).

Eugenic principles contributed to negative attitudes toward PWIDD. Eugenics, from the Latin Eu- "good”, and Gen- "birth" is the idea that certain human lives are more desirable than others. To "better" humanity and improve the gene pool, those who possessed desirable characteristics were encouraged to procreate and those with less desirable characteristics, including PWIDD, were not. After World War II, eugenics was no longer endorsed or practiced, but this moral recognition did not erase eugenic thought, nor extend to improving institutional care for people with disabilities.

The social model of disability...further undergirded the deinstitutionalization movement.The number of PWIDD living in institutions peaked in the 1960s (Nehring, 2001), when multiple international events (Penhurst and Willowbrook in the US; Winterbourne in the UK) called attention to inhumane and dehumanizing institutional conditions (Conroy & Radley, 1985; Disability Justice, 2022; Flynn, 2012). The intersection of media exposure, the civil rights movement, and the United Nations (1971) Declaration on the Rights of Mentally Retarded Persons prompted the deinstitutionalization of people with disabilities into community settings. The deinstitutionalization movement was underpinned by the philosophy of normalization (Wolfensberger, 1972) which promoted the idea that PWIDD should condition and pattern life as close as possible to the general population. Also influencing the deinstitutionalization movement was social role valorization which posits that, to improve the conditions and treatment of marginalized peoples, they must be afforded opportunities to hold valued social roles in the community (Wolfensberger, 2011). The social model of disability (Chappell et al., 2001), in which barriers in society are responsible for disability, rather than the person's impairment, further undergirded the deinstitutionalization movement.

...supports for PWIDD have largely shifted to a variety of home and community-based settings...Access to Care. With downsizing and closure of many institutionalized care settings, supports for PWIDD have largely shifted to a variety of home and community-based settings, including group homes, day services, foster care, and other independent and supported living arrangements (Nehring, 1999). While it was anticipated that the generic healthcare system would meet the needs of PWIDD living in the community, healthcare providers are often ill-prepared to meet their specialized needs (Ervin et al., 2014). PWIDD encounter multiple challenges in coordinating and accessing disparate primary, specialty, and disability care services (Ervin et al., 2014). As a result, PWIDD face many health inequities, including higher rates of preventable mortalities and comorbidities, and less access to health promotion and prevention services (Ervin et al., 2014). Unfortunately, in some cases the inadequacy of community resources for PWIDD has resulted in inappropriate re-institutionalization of PWIDD into nursing homes and prisons (Beadle-Brown et al., 2007).

...challenges associated with deinstitutionalization are consistent across countries [but]...nursing approaches to bridging the gaps in care differ. Comparison of Service Delivery. While challenges associated with deinstitutionalization are consistent across countries participating in our global collaboratory, nursing approaches to bridging the gaps in care differ. In the UK and Ireland, acute care IDD liaison nurses provide support for PWIDD, caregivers, and hospital staff throughout the person's hospital journey. These nurses provide specific attention to ensuring communication, care coordination and reasonable adjustments to care to meet individualized needs of PWIDD (Tuffrey-Wijne et al., 2013). In Wales and England, learning disability liaison nursing teams, based in secondary healthcare (i.e., specialty care provided via referral), have developed a network of learning disability champions who are healthcare workers trained by liaison nurses to understand learning disabilities, anticipate reasonable adjustments, and provide safe and effective person-centered care to PWIDD (Jennings, 2019; The Paul Ridd Foundation, 2020). Learning disability champions function as an advocate for PWIDD in their clinical area and share information from the learning disability liaison nurse with their clinical healthcare team (Jennings, 2019).

In Queensland, Australia, nurse navigators support health literacy, care coordination, and self-management needs of PWIDD and other chronic health conditions to reduce overall care costs and improve quality of life (Harvey et al., 2021). A nurse liaison is part of the regional District Health Board in New Zealand (NZ). In the US and Canada, no such liaison role uniformly exists to address unique needs of PWIDD, posing additional challenges to nurses who receive minimal, if any, IDD training within generalist nursing education programs.

Nursing Education Related to Caring for PWIDD

Only in Ireland and the UK are curriculum options about IDD taught as a distinct specialty pathway within undergraduate nursing programs. Formal education related to IDD varies between countries, affecting nurses’ ability to provide compassionate, knowledgeable, culturally sensitive or competent, and developmentally-appropriate care (ANA Ethics Advisory Board, 2020; Fisher et al., 2020). Only in Ireland and the UK are curriculum options about IDD taught as a distinct specialty pathway within undergraduate nursing programs. Minimal education or clinical opportunities related to IDD exist in the US, Canada, Australia, and NZ within nursing pre-licensure or graduate nursing programs (Cashin et al., 2021; Fisher et al, 2020). Funding issues, an overloaded curriculum, time, and few nursing faculty content experts are frequently identified as reasons that educational preparation for nurses related to IDD is lacking (Fisher, et al, 2020, Smeltzer, 2021). In Australia, for example, a survey of 31 nursing schools showed that content related to IDD was taught in 15 of the 31 schools; however, most schools did not have a faculty member with any IDD experience (Trollor et al., 2018).

New Zealand. The experience in New Zealand with development and closure of IDD nurse training programs is illustrative. In the 1960s, legislation prompted development of hospital-based training programs for specific scopes of nursing practice. One such scope was care of PWIDD (Watson et al., 1985). In 1971, Dr. Helen Carpenter of the WHO addressed New Zealand's Department of Health and promoted changes in nursing education away from individual specialties toward preparation of generalist nurses for a comprehensive scope of practice (Department of Health, 1971). This coincided with the deinstitutionalization movement which, while necessary for the human rights and well-being of PWIDD, began the erosion of education about working with PWIDD.

While not all PWIDD require nursing support, there remains a clear demand for nursing within the community context.Within the initial generalist nursing education, students had a six-week course comprised of one to two weeks of theory and four to five weeks of clinical placement. Such content has been reduced over time and is now either non-existent or decreased to a limited number of in-person or online lectures. The rationale is that community settings in which PWIDD live are no longer staffed by nurses, rather with an unregistered workforce. Ensuring a sufficiently skilled workforce continues to be problematic and, as with many other countries, NZ has had a reliance on recruiting Registered Nurse (Learning Disability) RN(LD) nurses from the UK.

United Kingdom. The UK has the most developed system of nursing education related to IDD, and its continuing challenges and development are informative. In 1919, the Nurses Registration Act acknowledged mental deficiency nursing, now called RN(LD), which remains today as one of four direct entry degree level qualifications (the other three are Adult, Child, and Mental Health Nursing (The Health Foundation, 2022). Across all four fields of nursing practice, students are required to achieve outcomes specified in standards published in The Standards of Proficiency for Registered Nurses (NMC, 2022). These include basic education relating to the needs of PWIDD for all nursing students regardless of their chosen field.

In addition, students receive specific education appropriate to their chosen field. For example, at the University of South Wales, all nursing students complete all modules. Needs of PWIDD are explored within the generic elements of the module, thus promoting awareness amongst all students. Students who specialize in IDD then engage in field-specific activities such as seminars. Although responsibility for the standards of nurse education is set at a UK level (NMC, 2022), there are differences in the context within which RN(LD)s work across the UK. For example, it has been over two decades since England last produced a governmental white paper to provide a strategic vision related to care and support for PWIDD. In Wales, the development of services has been driven by the Improving Lives Program (Welsh Government, 2018) which includes several key actions to reduce health inequalities.

...the consequence of limited content in undergraduate instruction leaves nurses unprepared to assess and address the range of needs of PWIDDAs identified, the consequence of limited content in undergraduate instruction leaves nurses unprepared to assess and address the range of needs of PWIDD (Lewis et al., 2017). Further, concerns regarding negative attitudes, impact on quality of care provided, challenges with access to care, and potential health inequities due to the lack of education and understanding of PWIDD are significant (Fisher et al., 2020). There is a global resurgence to identify and take steps to rectify this gap in knowledge, skills, and attitude, particularly given the increased health complexity and longevity of this population. To address this knowledge gap, we offer several tangible actions that any nurse can take to optimize the nursing care and support for PWIDD.

Action Steps for All Nurses to Reduce Health Inequities of PWIDD

Practice Self-Awareness & Personal/Professional Development

In the absence of education and experience in caring for PWIDD, it is not uncommon for nurses to hold the same stigmatizing misconceptions about PWIDD as the general population (Desroches, 2019). Common misperceptions are that PWIDD are "innocent" and "child-like." Therefore, it is assumed they are not capable of understanding basic health teaching and are not sexually active (Ditchman et al., 2017). Misconceptions lead some to believe that PWIDD do not experience pain to the same degree as people without disability (Drainoni et al., 2006) and that the quality of life of PWIDD is poor (Iezzoni, 2006). These misconceptions can affect the care that PWIDD receive from even the most well-intentioned nurses.

...it is not uncommon for nurses to hold the same stigmatizing misconceptions about PWIDD as the general populationNurses who hold erroneous beliefs may be less likely to involve PWIDD in health teaching; recommend preventive and reproductive health screenings; assess and treat pain; and advocate for life-sustaining measures for a PWIDD who faces a critical illness. To reduce these healthcare disparities, nursing praxis is needed. Nursing praxis is a transformation of nursing practice to eliminate injustices in care by applying nursing knowledge. In the absence of IDD-related knowledge in nursing education, nurses must actively desire to seek such knowledge. Recognizing and valuing the historic position of nurses as change agents for social justice may prompt motivation for learning.

Nurses can acquire this knowledge in a few ways. First, they can use self-reflection about their own attitudes regarding care for PWIDD. Questions to ask oneself may include: What assumptions am I making about this person and their abilities? How are my thoughts and beliefs about this person's situation influencing the care I provide? Second, nurses can gain experiential knowledge of PWIDD by overcoming any reticence and embracing the opportunity to provide clinical nursing care for PWIDD when it arises. Likewise, clinical nursing instructors can seek to include patients with IDD when identifying nursing student assignments.

Experiential learning can also occur through personal contact with PWIDD outside of the healthcare setting.Experiential learning can also occur through personal contact with PWIDD outside of the healthcare setting. For example, conversations with PWIDD and their families in the community and through participation in inclusive community programs, such as Special Olympics International and Best Buddies, can be insightful. Lastly, professional organizations specific to IDD nursing offer educational webinars and continuing education for nurses to expand their knowledge base related to unique needs of PWIDD in healthcare settings. Table 1 presents a list of IDD nursing professional organizations and educational resources.

Table 1. IDD Nursing Professional Organizations and Educational Resources for Nurses

|

IDD Nursing Professional Organizations |

Contact Information |

|

Developmental Disabilities Nurses Association (USA and Canada) |

|

|

Irish Nurses and Midwives Organisation (INMO) Registered Nurse Intellectual Disability (RNID) Section (Ireland) |

|

|

National Disability Nurse Branch site for New Zealand College of Mental Health Nurses. |

|

|

Professional Association of Nurses in Developmental Disability Australia (Australia) |

|

|

Royal College of Nursing Learning Disability Nursing Forum (UK) |

https://www.rcn.org.uk/Get-Involved/Forums/Learning-Disability-Nursing-Forum |

|

Educational Resources |

|

|

The American Academy of Developmental Medicine and Dentistry (AADMD) |

|

|

American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities |

|

|

The Arc of the United States |

http://www.thearc.org/what-we-do/public-policy/policy-issues |

|

Canadian Consensus Guidelines on Primary Care for Adults with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (2018) |

|

|

Community Living and Participation for People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities |

|

|

Complex Moral Issues: End of Life Decisions for Adults with Significant Intellectual Disabilities |

|

|

Delivering Quality Healthcare for People with Disability |

https://www.sigmamarketplace.org/delivering-quality-healthcare-for-people-with-disability |

|

Department of Health, United Kingdom. Valuing People (2001) |

https://www.gov/uk/government/ uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/ 250877/5086.pdf |

|

Disability and Public Health (text) |

https://ajph.aphapublications.org/ doi/book/10.2105/9780875531915 |

|

Donald Beasley Institute, a National NZ independent Disability, Research and Education non-profit organization |

|

|

Guidelines on Caring for People with a Learning Disability in General Hospital Settings |

https://www.rqia.org.uk/RQIA/files/ 41/41a812c6-fee8-45ba-81b8-9ed4106cf49a.pdf |

|

Health Communication Tools for PWIDD |

|

|

International Consensus Guidelines Management for Type 2 Diabetes in Intellectual Disabilities |

|

|

Learning Disability Framework |

https://www.skillsforhealth.org.uk/info-hub/learning-disability-and-autism-frameworks-2019/ |

|

Mencap |

|

|

National Task Group on Intellectual Disabilities and Dementia Practices |

|

|

NHS Accessible Information Standard |

|

|

NHS England (2019) Core Capabilities Framework for Supporting People with a Learning Disability. |

|

|

Palliative Care for People with Learning Disabilities |

|

|

Practice Standards for Developmental Disability Nursing, 3rd edition (2020); includes DD Nursing Professional Practice Model |

|

|

Resources in Developmental Disabilities and Coping with Grief, Death, and Dying |

http://rwjms.rutgers.edu/boggscenter/ documents/EndofLifeResources12013.pdf |

|

Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists- 5 Good Communication Standards |

http://www.betterlives.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/RCSLT-Good-standards-v-13-May-13-.pdf |

|

Shaping the Future of Intellectual Disability Nursing in Ireland |

|

|

Social media groups Learning and Intellectual Disability Nursing Academic Network (LIDNAN) (UK and Ireland) Facebook Group 'Positive choices' Learning Disability Nurses are fantastic society. (UK and Ireland) Facebook group is for student nurses who are studying to be learning/intellectual disability nurses. Positive Commitment - a partner to Positive Choices (UK and Ireland) Facebook Group for Nursing Professionals specialised in the care of People with a Learning/Intellectual Disability #WeLDNurses |

https://www.facebook.com/groups/ 1176665819010632/?_rdr https://www.facebook.com/groups/11271315956 |

|

United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities |

|

|

University of Queensland Intellectual Disability Healthcare |

https://www.edx.org/xseries/intellectual-disability-healthcare |

|

World Health Organization World Report on Disability |

http://www.who.int./disabilities/ world_report/2011/report.pdf |

Optimize Communication

PWIDD can experience communication challenges when attending healthcare settings When PWIDD experience delays in development of communication and social skills, these impairments can affect their capacity to develop interpersonally and integrate into society (Smith et al., 2019). Challenges experienced by PWIDD often involve comprehension and understanding of communicated information; the capacity to verbally share information; sensory impairments that may not be obvious; and physical disabilities that may impair ability to signal their intentions or needs (Griffiths, 2017; NHS England, 2019). In these circumstances, people who know the person well may understand them better (e.g., parents, siblings, caregivers) and can provide support (Griffiths, 2017).

PWIDD can experience communication challenges when attending healthcare settings (Regulation and Quality Improvement Authority [RIQA], 2018). Therefore, nurses need to understand ways to support effective communication with them (NHS England, 2019). Communicating effectively requires an understanding of a person’s expressive and receptive communication and considers individual speech, language, sensory needs and preferences (Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists, 2013). Nurses need to consider reasonable adjustments or accommodations to facilitate communication (e.g., content, pace, and mode of communication during healthcare encounters). Table 2 offers many strategies for effective communication in healthcare settings.

Table 2. Tips to Communicate Effectively with PWIDD in Healthcare Settings

|

Communication Tip |

Source |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note. Adapted from guidance provided by Doyle et al., 2016; Griffiths, 2017; and RIQA, 2018.

Make Reasonable Adjustments/Accommodations

Reasonable adjustments can also incorporate system-level modifications to foster a physical and social environment...Reasonable adjustments identified in the Equality Act of 2010 (UK Government, 2013), or accommodations (United Nations, 2006) can be defined as adjustments to usual care practices, that do not impose undue burden, to ensure a person with disabilities can experience a service or activity on an equal basis with others. Reasonable adjustments can also incorporate system-level modifications to foster a physical and social environment, as well as a workplace culture where all staff are knowledgeable about myriad ways to adjust care for people with IDD (Moloney et al., 2021).

...that knowledge about reasonable adjustments by registered nurses is low...Although we cannot always anticipate individual needs, we should anticipate that PWIDD will use our services and therefore we should expect and design care systems with inclusivity and reasonable accommodations in mind. A recent Australian study highlighted that knowledge about reasonable adjustments by registered nurses is low, with 59.6% self-reporting a lack of familiarity with the term, indicating a need for targeted education (Wilson et al., 2021). One theoretical framework developed in healthcare practice to enable nurses to identify adjustments is the 4C Framework (Marsden & Giles, 2017). This framework describes four categories of potential reasonable adjustments for care of PWIDD: Communication, Choice Making, Collaboration, and Coordination. Use of this framework supports the nurse to develop a care plan that is person-centered and responsive to individual needs.

An example of a reasonable adjustment related to communication might be use of a health communication tool. An example of a reasonable adjustment related to communication might be use of a health communication tool. Such a tool provides information on key health and support needs of a PWIDD to enable healthcare professionals to provide safe, timely, and appropriate support. While these tools are used internationally, content, format, and length vary widely. This creates a patient safety issue because documents may not be widely recognized or appropriately used by health professionals, and key information may be missing (Northway et al., 2017). Accordingly, Northern Ireland (Health Services Executive [HSE], 2021) and Wales (Public Health Wales, 2020) have developed single health communication tools to be used across services in their respective countries. See Table 1 above for additional information.

Provide Comprehensive and Disability-Sensitive Clinical Care

Though PWIDD may have disability-specific health needs, essentially, they have the same health needs as the general population. Thus, it is important for nurses to address both sets of needs to optimize health. PWIDD are less likely to receive routine health promotion and screenings, including mental and oral health services and cancer screenings (Ervin et al., 2014). This can be attributed, in part, to diagnostic overshadowing, which refers to the healthcare provider's focus on a person's disability, to the exclusion of primary physical, mental, and emotional needs (Blair, 2017).

Nurses must be aware that PWIDD may have differing presentation modes which may be interpreted as simply behavior challenges. PWIDD are at increased risk of "the fatal five," or the five most common preventable causes of mortality among the population: aspiration, bowel obstruction (constipation is often a precursor), seizures, dehydration, and sepsis (IntellectAbility, 2022). Nurses must be aware that PWIDD may have differing presentation modes which may be interpreted as simply behavior challenges. PWIDD who are minimally verbal may express needs through behavioral manifestations. For example, self-injurious behavior (e.g., hitting oneself or head banging) may signal headache or dental pain. Nurses must continually recognize that all behavior is communication, and health related causes for behavioral changes need to be investigated prior to attributing behavior to an underlying disability. When possible, consulting with the individual who knows the PWIDD best is optimal for establishing presenting norms. It is important for nurses to know that PWIDD are at high risk for sexual abuse and exploitation, often by a person known to them, that is often underreported because of communication barriers, myths, and misconceptions about PWIDD including credibility, fear, and lack of resources (McGilloway et al., 2020). Recognizing this risk, nurses can conduct routine screenings for abuse, ensure their awareness of the signs of abuse, and promptly report any suspicions of abuse (Koetting et al., 2011).

Elicit the Expertise of PWIDD and their Caregivers

PWIDD often require support for daily living needs and community engagement. The majority of PWIDD live in the community with a family caregiver, usually a parent (Braddock et al., 2013). PWIDD may also be supported by paid caregivers: variously referred to as direct care staff, direct care professionals, direct support staff, residential staff, personal care attendants. No matter the terminology, the emphasis of the role is on support for PWIDD to achieve their individualized goals, as opposed to providing care to a passive recipient. This action respects human dignity and autonomy and is consistent with the nursing paradigm concept of person-centered care.

Nurses can demonstrate person-centeredness with PWIDD by eliciting individual preferences and offering choices; offering support for them to be as independent as possible; and primarily communicating directly with the person who needs care, while also intentionally partnering with the caregiver, as needed. Recognizing that family and paid caregivers have experience supporting and meeting needs of the PWIDD, nurses can demonstrate respect for this expertise by including them in client assessment, care planning, and patient teaching, when appropriate and acceptable to the PWIDD. Nurses can also support the well-being of PWIDD by ensuring that caregivers have access to necessary care-related resources, including respite services, emotional support, financial assistance, and connections for referrals. As family caregivers age, a major source of stress and concern is identifying and arranging alternative living and care support. The proactive nurse can guide families and PWIDD through these transitions by facilitating connections with appropriate and available community-based resources (McKiernan et al., 2015; Trip et al., 2019).

Plan and Prepare for Acute Care Transitions

Breakdowns in providing person-centered culturally competent care for PWIDD have been identified before, during, and after acute care episodes Hospitals and medical centers are responsible to provide quality clinical care specific to patients’ cultural, language, and other needs based on their specific characteristics (The Joint Commission, 2010). Breakdowns in providing person-centered culturally competent care for PWIDD have been identified before, during, and after acute care episodes (Ailey et al., 2015; 2016). To reduce negative health outcomes associated with hospital care, nurses can employ several strategies. Prior to a planned hospital admission, it is important for the nurse to gather sufficient information about the person's communication, sensory, safety, and specialized resource needs. During the hospital stay, nurses can optimize the care environment, such as maintaining routines to the extent possible, addressing sensory needs, and determining and communicating what the PWIDD finds calming and/or anxiety producing or frightening. Additionally, nurses can advocate for access to specialized resources, such as sensory resources (e.g., weighted blankets), and communication devices and supports.

Clear communication and documentation of individualized care needs is essential for continuity of care...Clear communication and documentation of individualized care needs is essential for continuity of care between hospital units and facilities, including documentation of key support persons and decision makers. Nurses play an important role in identifying and addressing deficiencies in discharge planning. Hospitals can improve system-wide care by offering better staff training concerning care needs of PWIDD; enhancing electronic medical records (EMR) systems with questions specific to common needs of this population; improving EMR systems so staff can easily obtain information about key support persons and decision makers; ensuring documentation of discharge instructions, including noting the discharge recipient of the PWIDD; and offering better staff training on discharge planning regarding coordination with family and community-based caregivers (Ailey et al., 2015; 2016).

Engage in Advocacy

Whether practicing in a clinical or community-based setting, every nurse has an inherent responsibility as a patient advocate. In this role, it is essential for nurses to support self-determination with respect to healthcare needs and wishes and social environmental needs (i.e., where one desires to live, work, worship, age) of each PWIDD (Developmental Disabilities Nurses Association [DDNA], 2020). To effectively do so, each nurse must first recognize their own personal attitudes and biases about PWIDD, as previously mentioned.

Beyond this recognition, rather than a traditional medical model in which a person’s plan of care is largely determined, managed, and evaluated by healthcare professionals or other supports, nurses can practice from a social or socioecological model. This type of model cultivates inclusion of the PWIDD as the central member of the interprofessional health team (Shogren, 2016; Smeltzer, 2021).

The team role focuses on advocacy within a person-centered partnership with individuals and their natural supports. The nurse, as a knowledgeable advocate for PWIDD, can be an opportune leader and coordinator of the team (DDNA, 2020). The team role focuses on advocacy within a person-centered partnership with individuals and their natural supports. Barring debilitating illness, to the extent the person can participate, the team employs a strengths-based approach to facilitate capacity to self-identify a health and wellness care plan and desired outcomes in the context of individual unique circumstances. This includes, as appropriate, empowering personal choice with respect to services and supports and providing the opportunity to evaluate and request adjustment in them as needed (Shogren, 2016; Smeltzer, 2021; Tondora et al., 2020).

Multiple health equity frameworks offer a blueprint for nurses to effect widespread change at the systems level to address health inequities. Examples include the World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Office for Europe Health Equity Policy Tool (2019); the Public Health England (UK) Health Equity Assessment Tool (2021); and the U.S. National Council on Disability (NCD) Health Equity Framework (2022). Collectively these frameworks offer action steps to address root causes of inequities, including living conditions, employment opportunities, healthcare access, reasonable accommodations, education, and improved data collection. Use of such frameworks will mitigate effects of longstanding societal biases toward PWIDD.

Conclusion

One outcome of the COVID-19 pandemic has been global collaboration to address health inequities experienced by PWIDD.One outcome of the COVID-19 pandemic has been global collaboration to address health inequities experienced by PWIDD. This group of expert IDD nurses, the Global IDD Nursing Collaboratory, has offered within historical context and practical strategies for nurses to better understand the needs of PWIDD and thus better prepare to render quality nursing care when working with this population across healthcare settings.

Acknowledgment: We would like to thank Dr. Shirley McMillan for her thoughtful comments about the education of nurses in Canada regarding intellectual disability nursing. Shirley is now retired after over 25 years of service as a Clinical Nurse Specialist at Surrey Place Centre, in Toronto, Canada.

Authors

Kathleen Fisher, RN, MSN, CRNP, PhD

Email: Kmf43@drexel.edu

ORCID ID 0000-0001-6326-7157

Kathleen Fisher is a Professor of Nursing at Drexel University College of Nursing and Health Professions. Dr. Fisher’s research has focused on health outcomes, health promotion, quality of life, and advocacy with at-risk, diverse populations which includes people with intellectual and developmental disability.

Melissa L. Desroches, RN, CNE, PhD

Email: mdesroches@umassd.edu

ORCID ID: 0000-0001-5353-6907

Melissa Desroches is an Assistant Professor in the Community Nursing Department of the College of Nursing and Health Sciences at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth. Dr. Desroches’ research interests include improving health equity of people with developmental disabilities, with special attention to the impact of healthcare provider bias and quality of care and articulating and strengthening the voice of intellectual/developmental disability nursing.

Daniel Marsden, MSc, SCLD, RNLD, FHEA

Email: daniel.marsden@canterbury.ac.uk

ORCID ID: 0000-0002-9892-3174

Daniel Marsden is a Senior Lecturer and Professional Lead in Learning (Intellectual) Disabilities, School of Nursing, Midwifery and Social Work at Canterbury Christ Church University in the United Kingdom. Dr. Marsden’s research interests include health promotion, advocacy, and nursing practice in learning disability nursing.

Stacey Rees, PhD, MSc, BSc (hons), RN(LD)

Email: stacey.rees@southwales.ac.uk

ORCID ID: 0000-0001-9130-4509

Stacey Rees is a Lecturer at the University of South Wales. Dr. Rees’s research interests include nursing roles, patient safety, and community support for adults with learning(intellectual) disabilities.

Ruth Northway, PhD, MSc(Econ), RN(LD)

Email: ruth.northway@southwales.ac.uk

ORCID ID:0000-0001-8420-733X

Ruth Northway is Professor of Learning (Intellectual) Disability Nursing at the University of South Wales, UK. Dr. Northway’s research interests include the health and well-being of people with intellectual disabilities and the role of the nurse in identifying and addressing such needs.

Paul Horan, MA, MA(j.o.), PGDipCHSE, RNID, RNT

Email: pahoran@tcd.ie

ORCID ID: 0000-0002-8947-918X

Paul Horan is an Assistant Professor of Intellectual Disability Nursing, School of Nursing & Midwifery, Trinity College Dublin, University of Dublin, Ireland. His research interests in intellectual disabilities include health promotion, community health and reflective practice.

Judy Stych, DNP, RN, CDDN

Email: jscddn@charter.net

ORCID ID: 0000-0002-8740-1063

Judy Stych holds a DNP in Advanced Public Health Nursing from Rush University, Chicago, Illinois. She is a nurse consultant for the Wisconsin Department of Health Services within its Medicaid-waiver, long-term-care managed care program supporting frail elders and people with physical and/or developmental disabilities. She is President of the Developmental Disabilities Nurses Association (DDNA).

Sarah H. Ailey, PhD, RN, FAAN

Email: Sarah_H_Ailey@rush.edu

ORCID ID:0000-0003-2364-6149

Sarah H, Ailey is a Professor in the Department of Community, Systems and Mental Health Nursing, in the College of Nursing at Rush University, Chicago, IL. Dr. Ailey’s research and scholarly practice concentrate on improving the lives of people with disabilities, in particular intellectual disabilities, by translating research into practice within community and inpatient hospital settings.

Henrietta Trip, RN, DipNS, BN, MHealSc(NURS), PhD(Otago)

Email: henrietta.trip@otago.ac.nz

ORCID ID: 0000-0001-5844-3400

Henrietta Trip is a Senior Lecturer and Academic Lead of the Master of Health Sciences Programme with the Centre for Postgraduate Nursing Studies, University of Otago, Christchurch, New Zealand. Dr. Trip’s teaching and research focuses on self-determining approaches in the management of long-term conditions for people with IDD with a particular lens on meaningful access, social models, nursing education, workforce development and responsiveness.

Nathan Wilson, RN, BSS, MSc, PhD, GCertSc(Statistics)

Email: N.Wilson@westernsydney.edu.au

ORCID ID: 00000002-6979-2099

Nathan J. Wilson is an Associate Professor in the School of Nursing and Midwifery at Western Sydney University in Australia. Dr. Wilson’s research interests are in applied research that enhances the health, wellbeing and social participation of people with long-term disabilities, in particular people with intellectual and developmental disability.

References

Ailey S. H., Christopher B. A., Ramson, K., Schmidt, N., & Lapin, A. (2016). Tracer methodology 101: Using mock tracers to evaluate care of patients with intellectual disabilities, part 2. Joint Commission: The Source, 14(1), 4-6. http://www.fieldsinc.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/%C2%AEJCs1601B1_Tracer-Patients-with-Intellectual-Disabilities-22.pdf

Ailey S. H., Christopher B. A., Ramson, K., Schmidt, N., & Lapin, A. (2015). Tracer methodology 101: Using mock tracers to evaluate care of patients with intellectual disabilities, part 1. Joint Commission: The Source, 13(12), 4-6. https://healthmattersprogram.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Using-Mock-Tracers-to-Evaluate-Care-of-Patients-with-Intellectual-Disabilities-Part-1.pdf

American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD). (2022). Defining criteria for intellectual disability. Intellectual Disability. http://aaidd.org/intellectual-disability/definition#.WOuWxoWcHD

American Nurses Association (ANA) Ethics Advisory Board. (2020). ANA position statement: Nurse’s role in providing ethically and developmentally appropriate care to people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 26(1). https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol26No01PoSCol01

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA). (1991). Learning disabilities: Issues on definition [Relevant Paper]. Practice Policy. https://www.asha.org/policy/rp1991-00209/

Beadle-Brown, J., Mansell, J. and Turnpenny, A. (2007) Deinstitutionalization in intellectual disabilities. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 20(5),437-442. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0b013e32827b14ab

Blair, J. (2017) Diagnostic overshadowing: See beyond the diagnosis. Changing Values. http://www.intellectualdisability.info/changing-values/diagnostic-overshadowing-see-beyond-the-diagnosis

Braddock, D., Hemp, R., Rizzolo, M. C., Tannis, E. S., Heffer, L., Lulinkski, A., & Wu, J. (2013). State of the states in developmental disabilities 2013: The great recession and its aftermath. The American Association of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318249512_STATE_OF_THE_STATES_IN_DEVELOPMENTAL_DISABILITIES_2013_THE_GREAT_RECESSION_AND_ITS_AFTERMATH/link/59c00b900f7e9b48a29ba7d1/download

Cashin, A., Pracilio, A., Buckley, T., Kersten, M., Trollor, J., Morphet, J., Howie, V. & Wilson N. J. (2021). A survey of Australian registered nurses’ educational experiences and self-perceived capability to care for people with intellectual disability and/or autism. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 47(3). https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2021.1967897

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2022a). Facts about developmental disabilities. Developmental Disabilities Homepage. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/developmentaldisabilities/facts.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2022b). Facts about intellectual disability. Developmental Disabilities Homepage Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/childdevelopment/facts-about-intellectual-disability.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2022c) Autism and developmental disabilities monitoring (ADDM) network. Data & Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/addm.html#:~:text=CDC%20estimates%20that%20about%201%20in%2044%208-year-old,11%20communities%20across%20the%20United%20States%20during%202018

Chappell, A. L., Goodley, D. & Lawthom, R. (2001). Making connections: The relevance of the social model of disability for people with learning difficulties. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 29(2), 45-50. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1468-3156.2001.00084.x

Conroy, J. W., & Bradley, V. J. (1985). The Pennhurst Longitudinal Study: A report of five years of research and analysis. Reports. https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/pennhurst-longitudinal-study-combined-report-five-years-research-analysis-0

Department of Health. (1971). An improved system of nursing education for New Zealand, Report of Dr. Helen Carpenter World Health Organization short-term consultant. Wellington, New Zealand. https://www.moh.govt.nz/notebook/nbbooks.nsf/0/238A8BFAE79C2B814C2565D70018FF82/$file/38212M.pdf

Desroches, M. L., Fisher, K., Ailey, S., Stych, J., McMillan, S., Horan, P., Marsden, D., Trip, H., & Wilson, N. (2022). Supporting the needs of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities 1 year into the COVID-19 pandemic: An international, mixed methods study of nurses' perspectives. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 19(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12411

Desroches, M. L., Ailey, S. H., Fisher, K., & Stych, J. (2021a). Impact of COVID-19: Nursing challenges to meeting the care needs of people with developmental disabilities. Disability and Health Journal, 14(1), 101015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.101015

Desroches, M. L., Fisher, K., Ailey, S. H. & Stych, J. (2021b). “We were absolutely in the dark”: Manifest content analysis of developmental disability nurses’ experiences during the early COVID-19 pandemic. Global Qualitative Nursing Research, 8, 1-9. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/23333936211051705

Desroches, M. L. (2019). Nurses' attitudes, beliefs, and emotions toward caring for adults with intellectual disabilities: An integrative review. Nursing Forum, 55(2), 211-222 https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12418

Developmental Disabilities Nurses Association (DDNA). (2020). Practice standards of developmental disability nursing (3rd ed.). High Tide Press.

Disability Justice. (2022). Reform of institutions and closing of institutions. Basic Legal Rights. https://disabilityjustice.org/reform-and-closing-of-institutions/

Ditchman, N., Easton, A. B., Batchos, E., Rafajko, S., & Shah, N. (2017). The impact of culture on attitudes toward the sexuality of people with intellectual disabilities. Sexuality and Disability, 35(2), 245–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-017-9484-x

Doyle, C., Byrne, K., Fleming, S., Griffiths, C., Horan, P., Keenan, P. (2016). Enhancing the experience of persons with intellectual disabilities who are accessing healthcare. Learning Disability Practice, 19(6),19-24. https://journals.rcni.com/learning-disability-practice/enhancing-the-experience-of-people-with-intellectual-disabilities-who-access-health-care-ldp.2016.e1752

Drainoni, M., Lee-Hood, E., Tobias, C., Bachman, S. S., Andrew, J., & Maisels, L. (2006). Cross-disability experiences of barriers to health-care access: Consumer perspectives. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 17(2), 101-115. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F10442073060170020101

Ervin, D. A., Hennen, B., Merrick, J. & Morad, M. (2014). Healthcare for persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities in the community. Frontiers in Public Health, 2, 83. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2014.00083

Fisher, K., Robichaux, C., Sauerland, J., & Stokes, L. (2020). A nurse’s ethical commitment to individuals with intellectual & developmental disabilities. Nursing Ethics, 27(4), 1066-1076. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0969733019900310

Flynn, M. (2012). Serious case review: Winterbourne View Hospital. South Gloucestershire Safeguarding Adults Board. http://sites.southglos.gov.uk/safeguarding/adults/i-am-a-carerrelative/winterbourne-view/

Gleason, J., Ross, W., Fossi, A., Blonsky, H., Tobias, J. & Stephens, M. (2021) The devastating impact of COVID-19 on individuals with intellectual disabilities in the United States. NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/CAT.21.0051

Griffiths, C., (2017). Module 2 - Supporting people with intellectual disability to Communicate. In P. Keenan, C. Doyle. and O. P. Maguire (Eds.). Special Olympics Ireland Tutor Training Manual - Intellectual Disability Education Modules (3rd ed.). Special Olympics Ireland. https://annualreport.specialolympics.org/2017/

Harvey, C., Byrne, A.-L.,Willis, E., Brown, J., Baldwin, A., Hegney, A. D., Palmer, J., Heard, D., Brain, D., Heritage, B., Ferguson, B., Judd, J., Mclellan, S., Forrest, R., & Thompson, S. (2021). Examining the hurdles in defining the practice of nurse navigators. Nursing Outlook, 69(4), 686–695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2021.01.011

The Health Foundation. (2022). Nurses Registration Act 1919. Themes. https://navigator.health.org.uk/theme/nurses-registration-act

Health Services Executives (HSE). (2021) HSE health passport for people with intellectual disabilities. HSE. Retrieved from: https://healthservice.hse.ie/filelibrary/onmsd/hse-health-passport-for-people-with-intellectual-disability.pdf

Henderson, A., Fleming, M., Cooper, S. A., Pell, J. P., Melville, C., MacKay, D. F., Hatton, C., & Kinnear, D. (2022) COVID-19 infection and outcomes in a population-based cohort of 17,173 adults with intellectual disabilities compared with the general population. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 76(6), 550-555. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2021-218192

Iezzoni, L. I. (2006). Make no assumptions: Communication between persons with disabilities and clinicians. Assistive Technology, 18(2), 212-219. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400435.2006.10131920

IntellectAbility. (2022). The fatal five fundamentals. Academy. https://replacingrisk.com/idd-staff-training/the-fatal-five-fundamentals/

Jennings, G. (2019). Introducing learning disability champions in an acute hospital. Nursing Times, 115(4), 44-47. https://cdn.ps.emap.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2019/03/190327-Introducing-learning-disability-champions-in-an-acute-hospital.pdf#:~:text=Addressing%20the%20needs%20of%20hospital%20inpatients%20with%20learning,has%20a%20network%20of%20110%20learning%20disability%20champions

The Joint Commission. (2010, August 4). Joint Commission publishes new guide for advancing patient-centered care. News release. https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2010/08/04/1235127/0/en/Joint-Commission-Publishes-New-Guide-for-Advancing-Patient-Centered-Care.html

Koetting, C., Fitzpatrick, J. J., Lewin, L., & Kilanowski, J. (2012). Nurse practitioner knowledge of child sexual abuse in children with cognitive disabilities. Journal of Forensic Nursing, 8(2), 72-80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-3938.2011.01129.x

Landes, S. D., Turk, M. A., Formica, M. K., McDonald, K. E., & Stevens, J. D. (2020). COVID-19 outcomes among people with intellectual and developmental disability living in residential group homes in New York State. Disability and Health Journal, 13(4), 100969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.100969

Lewis, P., Gaffney, R.J., & Wilson, N.J. (2017). A narrative review of acute care nurses’ experiences nursing patients with intellectual disability: Underprepared, communication barriers and ambiguity about the role of caregivers Journal of Clinical Nursing 26(11-12), 1473–1484, https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13512

Marsden, D., & Giles, R. (2017). The 4C framework for making reasonable adjustments for people with learning disabilities. Nursing Standard, 31(21), 45–53. https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.2017.e10152

McGilloway, C., Smith, D. & Galvin, R. (2020). Barriers faced by adults with intellectual disabilities who experience sexual assault: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 31(1), 51-66. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12445

McKiernan, K., Shaffert, R., & Murray, N. (2015). Aging caregivers and the adults with I/DD who live with them. Summer Leadership Institute. https://thearc.org/?file=Shaffert.McKiernan.Aging-Caregivers.pdf

Moloney, M. Hennessy, T., & Doody, O. (2021). Reasonable adjustments for people with intellectual disability in acute care: A scoping review of the evidence. BMJ Open,11(2), e039647. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039647

National Council on Disability (NCD). (2022). Health Equity Framework. Publications. https://ncd.gov/publications/2022/health-equity-framework

Nehring, W. (2001). A history of nursing in the field of mental retardation and developmental disabilities. Nursing History Review, 9(1), 232-234. http://dx.doi.org/10.1891/1062-8061.9.1.232

NHS England. (2019). Core capabilities framework for supporting people with a learning disability. https://www.skillsforhealth.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Learning-Disability-Framework-Oct-2019.pdf

Northway, R., Rees, S., Davies, M., & Williams, S. (2017). Hospital passports, patient safety and person-centered care: A review of documents currently used for people with intellectual disabilities in the UK. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26, 5160 – 5168. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14065

Nursing & Midwifery Council (NMC). (2022). Standards of proficiency for registered nurses. Standards. https://www.nmc.org.uk/standards/standards-for-nurses/standards-of-proficiency-for-registered-nurses/

The Paul Ridd Foundation. (2020). Supporting people with learning disabilities to access equal healthcare. About Us. https://paulriddfoundation.org/our-vision/

Public Health England. (2021) Health equity assessment tool (HEAT). Public Health. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-equity-assessment-tool-heat

Public Health Wales. (2020). Once for Wales health profile. Services and Teams. https://phw.nhs.wales/services-and-teams/improvement-cymru/our-work/learning-disability-health-improvement-programme/health-profile/health-profile-for-professionals/

Regulation and Quality Improvement Authority (RIQA). (2018). Guidelines on caring for people with a learning disability in general hospital settings. RQIA. https://www.rqia.org.uk/RQIA/files/41/41a812c6-fee8-45ba-81b8-9ed4106cf49a.pdf

Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists. (2013). Five good communication standards: Reasonable adjustments to communication that individuals with learning disability and/or autism in specialist hospital and residential settings should expect. Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists. http://www.betterlives.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/RCSLT-Good-standards-v-13-May-13-.pdf

Shapiro, J. (2020, December) Oregon hospitals didn't have shortages. So why were disabled people denied care? NPR. https://www.npr.org/2020/12/21/946292119/oregon-hospitals-didnt-have-shortages-so-why-were-disabled-people-denied-care

Shogren, K. (2016). Self-determination and self-advocacy. In Critical issues in intellectual and developmental disabilities: Contemporary research, practice, and policy (pp.1-18). American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities.

Smeltzer, S. (2021). Delivering quality healthcare for people with disability. Sigma Theta Tau International Honor Society of Nursing.

Special Olympics. (2022). What is intellectual disability? About. https://www.specialolympics.org/about/intellectual-disabilities/what-is-intellectual-disability

Smith, M., Manduchi, B, Burke, É., Carroll, R., McCallion, P., & McCarron, M. (2019). Communication difficulties in adults with intellectual disability: Results from a national cross-sectional study. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 97, 103557. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2019.103557

Tondora, J., Croft, B., Kardell, Y., Camacho-Gonsalves, T., & Kwak, M. (2020, November). Five competency domains for staff who facilitate person-centered planning. NCAPPS. https://ncapps.acl.gov/docs/NCAPPS_StaffCompetencyDomains_201028_final.pdf

Trip, H., Whitehead, L., Crowe, M., Mirfin-Veitch, B., & Daffue, C. (2019). Aging with intellectual disabilities in families: Navigating ever-changing seas – A theoretical model. Qualitative Health Research, 29(11), 1595-1610. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1049732319845344

Trollor, J. N., Eagleson, C., Turner, B., Salomon, C., Cashin, A., Iacono, T., Goddard, L., & Lennox, N. (2018) Intellectual disability content within pre-registration nursing curriculum: How is it taught? Nurse Education Today, 69, 48-52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2018.07.002

Tuffrey-Wijne, I., Giatras, N., Goulding, L., et al. (2013). The role of the learning disability liaison nurse. In Identifying the factors affecting the implementation of strategies to promote a safer environment for patients with learning disabilities in NHS hospitals: A mixed-methods study (Chapter 9). NIHR Journals Library, 1(13). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK259497/

Turk, M. A., Landes, S. D., Formica, M. K., & Goss, K. D. (2020). Intellectual and developmental disability and COVID-19 case-fatality trends: TriNetX analysis. Disability and Health Journal, 13(3), 100942. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.100942

UK Government. (2013). Equality Act 2010: Guidance. Equality. http://www.gov.uk/guidance/equality-act-2010-guidance

United Nations. (20 December, 1971). Declaration on the rights of mentally retarded persons. General Assembly resolution 2856 (XXVI). https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/res2856.pdf

United Nations. (13 December, 2006). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. Resources. https://www.ohchr.org/en/resources/educators/human-rights-education-training/12-convention-rights-persons-disabilities-2006

U. S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office for Civil Rights. (2020). Bulletin: Civil rights, HIPAA, and the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Retrieved from https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/ocr-bulletin-3-28-20.pdf

Watson, J. E., Singh, N. N., & Woods, D. J. (1985). Institutional Services. In Singh, N.N., & Wilton, K.W. (Eds.). Mental Retardation in New Zealand, (pp 47-59). Whitcoulls Publishers.

Welsh Government. (2018). Learning disability Improving Lives programme. Retrieved from: Retrieved from: https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2019-03/learning-disability-improving-lives-programme-june-2018.pdf

Wilson, N. J., Pracilio, A., Kersten, M., Morphet, J., Buckely, T., Trollor, J. N., Griffin, K., Bryce, J., & Cashin, A. (2021). Registered nurses' awareness and implementation of reasonable adjustments for people with intellectual disability and/or autism. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 78(8), 2426-2435. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.15171

Wolfensberger, W. (2011). Social role valorization: A proposed new term for the principle of normalization. Mental Retardation, 49(6), 435-40. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-49.6.435

Wolfensberger, W., Nirje, B., Olshansky, S., Perske, R., & Roos, P. (1972). The principle of normalization in human services. National Institute on Mental Retardation. https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/wolf_books/1/

World Health Organization (WHO). (2019, May 24). Health equity policy tool. A framework to track policies for increasing health equity in the WHO European Region—Working document (2019). Publications. https://www.who.int/europe/publications/m/item/health-equity-policy-tool.-a-framework-to-track-policies-for-increasing-health-equity-in-the-who-european-region-working-document-(2019)

Wulf, W. A. (1989). The national collaboratory–a white paper. In: Lederberg, J. and Uncaphar, K. (Eds.), Towards a National Collaboratory: Report of an Invitational Workshop at the Rockefeller University, March 17–18 (Appendix A). National Science Foundation, Directorate for Computer and Information Science Engineering, Washington, D.C.