People with intellectual disabilities experience many health disparities including difficulties with access to healthcare, and a lack of appropriate and timely healthcare. Nurses are well placed to address such disparities. In the UK, this is a key focus of the role of specialist community learning (intellectual) disabilities nurses (CLDNs), as explained in our background section. Research relating to this aspect of their role is limited. This qualitative research study explored the role of the CLDN to support access to secondary healthcare. This article reviews our study methods, which included semi-structured interviews (n = 14) conducted with CLDNs using critical incident technique. These were subsequently transcribed and critical incidents (n = 74) analysed using thematic analysis. We describe in our findings four emerging themes: Proactive/Preparatory Work; Therapeutic Relationships; Coordination; and Influencing Healthcare Outcomes. Within each theme and several subthemes there is evidence of CLDNs identifying and removing or reducing barriers to effective and timely healthcare. The discussion section asserts that CLDNs use a range of strategies to support access to healthcare and with a focus on barriers, they promote health within a social model of disability. We conclude that, whilst specialist CLDNs do not exist in many other countries, the strategies they employ could be utilised by non-specialist nurses working both within the UK and elsewhere to enhance access and reduce health disparities for people with intellectual disabilities.

Key Words: Intellectual disability, health disparities, access to healthcare, nursing, critical incident technique

People with intellectual disabilities experience many health disparities...People with intellectual disabilities experience many health disparities including difficulties with access to healthcare, and a lack of appropriate and timely healthcare. Nurses are well placed to address such disparities, and in the United Kingdom (UK), this is a key focus of the role of specialist community learning (intellectual) disabilities nurses (CLDNs). This article reports on the qualitative findings of a study that explored the role that Community Learning Disability Nurses (CLDNs) in Wales play to support access to secondary/acute healthcare for people with intellectual disabilities (Rees, 2021). The term ‘intellectual disabilities’ will be used (as this is internationally recognised) except where reference is made to nurses who form the focus of this study. In this instance the term ‘learning disability’ will be used as a part of the acronym because this is the current terminology to refer to this group of nurses (i.e., CLDN) in the UK. Thus, within this article, the terms intellectual disability and learning disability are used slightly differently, but have the same meaning; CLDNs in their role support the population of individuals with an intellectual disability.

Background

There is international evidence that, as a group, people with intellectual disabilities experience health disparities when compared with the wider population (McMahon & Hatton, 2020). Whilst life expectancy for this group has increased over recent years, it remains some 20 years lower than for their non-disabled peers (O’Leary et al., 2018).

...health professionals often report that they lack the confidence and competence to effectively support people with intellectual disabilities in secondary healthcare settings...Several factors impact such disparities, including barriers that people with intellectual disabilities experience with access to appropriate and timely healthcare (McCormick et al., 2020). However, health professionals often report that they lack the confidence and competence to effectively support people with intellectual disabilities in secondary (i.e., acute) healthcare settings (Spassiani et al, 2020) because they often have not received education to take on this role (Hemm et al., 2015). Such educational and skills barriers can therefore negatively impact the healthcare received by those with intellectual disabilities.

Within the UK, pre-registration student nurses choose to specialise in one of four fields of practice rather than follow a generic programme as exists in many countries. Whilst all students, whichever field they have chosen, should receive education that enables them to identify and address health needs of people with intellectual disabilities, one of the four fields relates specifically to intellectual disabilities (Nursing and Midwifery Council [NMC], 2018). Nurses graduating from such programmes become Registered Nurses (Learning Disabilities) [RN(LD)s] and work in a range of settings to provide support for people with intellectual disabilities and families/carers.

A key focus of learning disability nurses in the UK is the promotion of health which includes supporting access to health care...A key focus of learning disability nurses in the UK is the promotion of health which includes supporting access to health care (Scottish Government, 2012). One role that has developed over recent years is the learning disability acute care liaison nurse. In this position, post holders predominantly work in acute (i.e., secondary) hospital settings to promote positive healthcare experiences for persons with an intellectual disability. They provide expert knowledge and skills to support acute healthcare staff, thus minimising harm and ensuring that reasonable adjustments/accommodations are in place (McCormick et al., 2020).

CLDNs work in multi-disciplinary, community-based teams to support people with intellectual disabilities who live in community settings.Another role undertaken by RN(LD)s in the UK is that of the Community Learning Disability Nurse. CLDNs work in multi-disciplinary, community-based teams to support people with intellectual disabilities who live in community settings. These teams may assist individuals who live independently, with their families, or in supported living provision, as well as within the educational and vocational settings they attend. Whilst some research has been undertaken regarding their overall role (Barr, 2006; Boarder, 2002; Mafuba et al., 2018; Mobbs et al., 2002), recent research is limited, and the role CLDN in supporting access to secondary healthcare has not been researched. This study sought to address this gap in knowledge.

Study Methods

Research Design and Objectives

Given a lack of previous research, an exploratory qualitative design was used. The overall question this research sought to answer was: Do community learning disability nurses (CLDNs) support adults with learning disabilities in Wales to access secondary healthcare? Specific objectives of the study were:

- To examine the support that is provided by CLDNs for adults with learning disabilities who access secondary healthcare in Wales.

- To identify barriers in accessing secondary healthcare and how these are overcome and removed by the CLDN.

Data Collection

Data were collected using critical incident technique embedded within qualitative, semi-structured interviews. Critical incident technique asks participants to reflect upon a specific episode of care that influenced a specific outcome (Flanagan, 1954) and has been used in research to understand nursing roles across multiple settings (Kemppainen, 2000).

Fitzgerald et al. (2008) argued that the recollection of the features of the incident is improved if participants know in advance what they will be talking about. Therefore, prior to the interview (usually around two weeks) participants were provided with a selection of positive and negative statements developed from a review of the literature and a small pilot study; this encouraged them to reflect on their experiences (see the Table for examples).

Table. Participant Instructions and Scenario Examples

|

Participant Instructions (provided pre-interview) |

Below is a list of scenarios that CLDNs sometimes may come across in practice in relation to supporting clients to access secondary healthcare. Please choose five or six items on the list and try to remember the occasions and the context when you felt like that. I am interested in how YOU felt, why those occasions are important to YOU and what YOU did. The interview will be based around discussion of your five or six selected scenarios. |

|

Scenario Examples |

|

|

|

Interviews (n = 14) involved a brief introduction to describe the purpose or aim of the study before participants were asked to recall specific incidents (five or six in total) linked to the statements that were previously provided (see Table). They were encouraged to reflect on the statements, and to recall specific incidents when they supported individuals to access secondary healthcare. Once the participant had identified an incident, to promote consistency the following probing questions were used, if the participant had not already answered them:

- What were the circumstances leading to that event?

- Exactly, what did you do?

- What was the outcome for the person with learning disabilities?

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval for this study to proceed was obtained from the Faculty of Life Sciences and Education Ethics Committee, University of South Wales. Approval from a National Health Service (NHS) ethics committee was not required as there was no patient involvement. However, permission to access participants was sought from the Research Governance Department in each Health Board.

A participant information sheet was provided for all those with an interest in participation to promote informed consent. Details were provided about what was involved in the study and usage and storage of data. Participation in the study was voluntary. Confidentiality was maintained by assigning a participant number to each transcript and a letter to each health board.

Participants

Allen (2017) asserted that in critical incident technique, the sample size depends on the needs and wishes of the researcher. It is recognised, however, that this advice might leave a researcher open to challenges regarding bias. Therefore, we sought to recruit participants from each of the seven geographical health boards in Wales to ensure that all were represented. Given the exploratory nature of the study, and the number of incidents that would be generated, two participants from each health board was deemed sufficient to achieve the study aims.

To be included in the study participants needed to meet the following inclusion criteria:

- Be a Registered Learning Disability Nurse

- Be practicing in Wales

- Be practicing in a multi-disciplinary community learning disability team (see background section above for description), and carrying a clinical caseload

- Have experience of liaising with secondary healthcare within last two years

In addition, they needed to work in either a Band 5 or Band 6 post (Band 5 is the starting grade for registered nurses in the UK and Band 6 is promotion from that grade). The rationale for this was that such nurses would be carrying a clinical caseload of people with an intellectual disability in a community setting.

Data Analysis

The mean interview (n = 14) length was 66 minutes. In total, 74 critical incidents were recorded, and data saturation was achieved.

Narrative Data. Each interview was transcribed and analysed using the approach to thematic analysis developed by Braun and Clarke (2006). Transcripts were read individually by the first author to ensure familiarisation with the data. Initial codes were generated, themes searched, and these themes reviewed before defining and naming them as such. A report was written to detail the final themes.

Trustworthiness. Several strategies were used to promote rigour, auditability, and trustworthiness. A sample of transcripts was independently analysed by the second author. Overall, there was a high level of agreement, and any differences were resolved through discussion. Because the project was part of a PhD dissertation, regular discussion and challenges through the supervisory process occurred, leading to further refinement of coding. Finally, a reflexive journal was maintained throughout to document decision making and the underlying rationale, hence providing a clear audit trail.

Findings: Emerging Themes

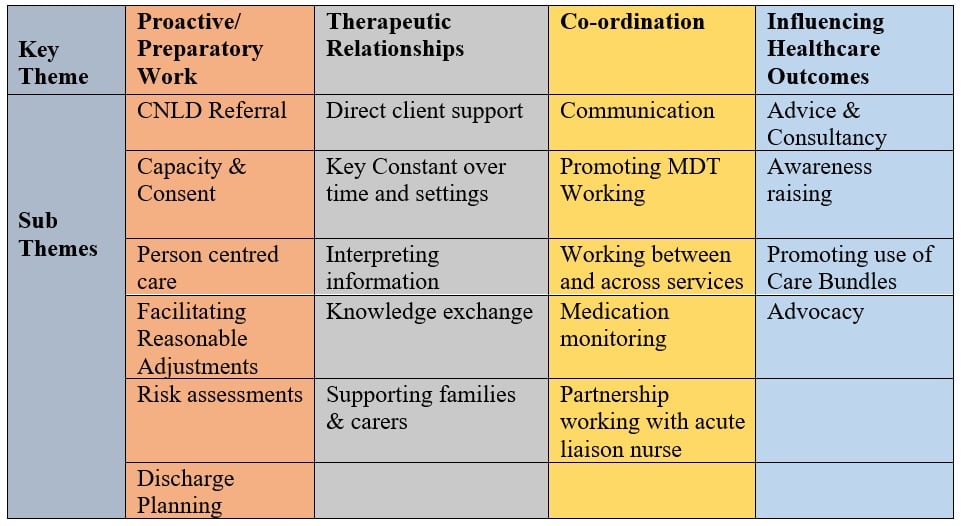

Four major themes and accompanying subthemes emerged from data analysis. These themes are detailed in the figure. Key findings are presented below, separated by the major themes. Supporting quotes from the data illustrate the various subthemes.

Figure. Overview of Study Themes and Subthemes

Key Theme #1: Proactive/Preparatory Work

A key barrier to access to healthcare for people with intellectual disabilities is a failure to adequately prepare...A key barrier to access to healthcare for people with intellectual disabilities is a failure to adequately prepare the individual, healthcare professionals, and the service. A recurring theme in the data, therefore, was the extensive work that CLDNs undertake to facilitate such preparation through identification of potential barriers and employing strategies to reduce or remove them. Sometimes this was the reason for referral for nursing input, as described below:

“The referral came into the team in anticipation and mum was to contact the team when she had the date for scan, the date came and it was within a week, this was too short notice in relation to the preparation that was needed.” (D8)

An important element of this preparation was to explore issues of capacity and consent and to ensure that legal requirements are adhered to:

“I knew if I was present, we could have a discussion around the procedure, and with the family there too, we could see if she had the understanding to consent to this complicated surgery.” (B3)

Where individuals are assessed as lacking capacity to consent, the CLDN may also be involved in (or even initiating) the ‘best interests’ procedures, as this participant described:

“I was involved in supporting the client to have a hip replacement, we had to have best interest meeting first, which I initiated as part of a decision-making process. We were concerned that they may not go through with it because of his learning disability. I attended the best interest meeting, and then pre-assessment meeting, this was arranged by the consultant” (E9)

One strategy to address such barriers is the use of health communication tools...When people with intellectual disabilities access secondary healthcare, difficulties can arise due to communication barriers. For example, healthcare staff may not possess the necessary skills to communicate effectively with them and people with intellectual disabilities may find it difficult to communicate information important to enable care (e.g,, medical conditions, medication, and means of communication). This can create a significant access barrier for timely, safe, and appropriate care.

One strategy to address such barriers is the use of health communication tools, sometimes referred to as hospital passports or ‘traffic light assessments.’ These documents provide key information for health professionals but are not always used even when available. Participants reported that they play a role in both ensuring such documents are in place and in encouraging healthcare staff to use them. In the first quote below, the CLDN specifically identified a potential communication barrier and had addressed this through completion of a health communication tool:

“He did not have a hospital passport, so I made sure I spoke to his family, and completed the passport so that doctors and nurses had all the information at hand” (D8)

“I had to constantly remind nurses to refer to the traffic light assessment” (A1)

...it may be necessary to make accommodations to the way in which a service is offered.To promote effective access to secondary healthcare for people with intellectual disabilities it may be necessary to make accommodations to the way in which a service is offered. This involves understanding individual needs, identifying aspects of service provision that may not be accessible, and using strategies to ensure that needs can be effectively met. Such adjustments may take several forms. CLDNs reported that they play a key role in ensuring that accommodations are in place to support preparation for accessing healthcare:

“…so we accessed easy read information, that kind of thing. We looked at videos on YouTube, I was able to show him those, and what would happen during investigation.” (G14)

CLDNs may also assist secondary care staff to make appropriate preparations to receive people with intellectual disabilities. This minimises the potential for distress and ensures that support is in place to meet needs:

“Prior to his admission, I visited the ward staff and went through his traffic light and talked to staff about his needs. He would need one to one support while he was there.” (B3)

“The receptionist already knew that we were going, so she was prepared and we got to see the radiologist as soon as we arrived. Due to the seamless process, the gentleman did not have the opportunity to get agitated and had x-ray with no problems.” (D7)

Linked to the need to ensure that reasonable adjustments/accommodations are in place, CLDNs also reported their involvement in preparatory risk assessments:

“we went through the risk assessment within the secondary care pathway to allow mum and dad to be there.” (G14)

“we completed a risk assessment around his stay in hospital, and from that it was highlighted that he needed support staff with him at all times” (B4)

Finally, whilst not always considered preparatory work, participants reported their involvement in preparing people with intellectual disabilities for discharge from hospital, sometimes having to take a lead in initiating this process:

“I initiated the discharge meeting, from the point of view that they would have had discussion with mum and dad but it was good to make it that more official and I think I minuted the meeting myself and bit it was good to write it down and clarify things as it came up.” (G14)

Key Theme #2: Therapeutic Relationships

Participants stressed the importance of developing therapeutic relationships...Participants stressed the importance of developing therapeutic relationships with the people with intellectual disabilities whom they support to facilitate their access to secondary healthcare. In some instances, this involved providing direct support during hospital visits:

“I always went for the oncology appointments, she would have three monthly checkups, she would go with her support worker for the injection but when she was seeing the doctor, I would go, it was, for her, it was important that I was there because sometimes the support worker would not always relay the correct information to me” (C5)

In the example above, the participant identified the potential for a breakdown in care to occur due to the failure of a support worker to convey accurate information. To ensure that the individual’s needs were met and that barriers to care were removed the CLDN took on the role of supporter and communicator.

A key aspect of the CLDN role that enables the provision of such support is that they often have contact with individuals with intellectual disabilities over a protracted period. They can build trust and have a good knowledge of the individual health needs and history as one participant explained:

“I would say I was the main hub, the main co-ordination, other people came in and out, lots of people were in and out of there, I was the stable one that stayed in there to ensure that those other things happened around her.” (D8).

Participants also highlighted a key role they play in interpreting healthcare information not only for individuals with intellectual disabilities, but also for families and carers:

“I understood what the specialist was saying, and I was able to interpret this into a language that my client could understand. I checked their understanding by asking her to explain what I had said” (A2)

“I needed to explain to staff about her changes in medication, and what they were for, they didn’t seem to know from a conversation with the house manager” (F11)

Building relationships with colleagues in secondary healthcare was also reported as important to facilitate access to such services. Negative interprofessional relationships can lead to barriers to healthcare for this population. However, positive relationships provide the opportunity for mutual learning which ensures that such patients can receive coordinated support from professionals:

“The work with the eating disorder nurse was a two-way process, I had never worked with anyone with eating disorder, and she had never worked with anyone with a learning disability so we both supported each other.” (D7)

Support for families and carers is essential when seeking to enhance access to secondary care. Participants reported providing such support:

“…and also, my role has been to help reduce the family’s anxieties. I am their point of contact, because mum, she didn’t think that it was her role to contact hospital or GP, she wouldn’t think like it.” (B3)

CLDNs described their role to promote coordination within and between services.Key Theme #3: Coordination

Secondary health services can be complex organisations and, given the complex health needs of people with intellectual disabilities, they may need to access different parts of the healthcare system. However, this may prove challenging and present a significant barrier for both individuals and their families/carers. CLDNs described their role to promote coordination within and between services. In particular, setting up effective systems of communication was reported as a key element:

“When I got involved, I arranged an overview of appointments. She is now discharged from ophthalmology clinic. All departments were seeing her individually and not communicating with each other. I arranged for consultants to copy each other into any correspondence” (B3)

This coordination was viewed as particularly important when individuals needed to access specialist services outside of their home health board area:

“He wore a spinal brace and all of his care with regards with curvature of the spine was monitored by (name of hospital), in a different health board, nearly two hours away.” (G14)

Where learning disability acute care liaison nurses were in post, CLDNs liaised with them to promote a coordinated approach:

“I had a phone call to say he had been admitted to hospital and from the staff at the house, so I filled in the referral. I referred to the health liaison nurse… and I arranged that I would go down on the Monday and see him. I went down and in fairness (name of nurse) met me there, and she got the staff to fill in the traffic light assessment etc., she was really helpful” (C5)

In addition, promoting coordination within multi-disciplinary teams was identified as essential to ensure appropriate care:

“My role was to link in with lots of other health professionals within my team. I contacted the other health professionals and told them about her diagnosis and we did joint visits to her house.” (D8)

Key Theme #4: Influencing Healthcare Outcomes

People with intellectual disabilities experience many health disparities (McMahon & Hatton, 2020). Promoting the best possible health outcomes through identification and removal of barriers that contribute to such disparities is central to the role of the CLDN. Participants identified a range of strategies used to facilitate this.

At times participants had felt it necessary to raise awareness amongst colleagues in secondary care.A key aspect of this role is providing advice and consultancy for colleagues who work in secondary care settings. In this context, CLDNs assist them to provide appropriate care for people with intellectual disabilities:

“So, I went to the senior nurse in charge of unscheduled care, and I just explained the situation…We sat down and we did a protocol so that was actually highlighted in his notes, as soon as he was admitted to Accident & Emergency, please refer to protocol and then it had all been signed off by the doctors that as soon as he went into A and E (they) would immediately call the senior guy on duty and use the Doppler to get access..” (G13)

At times participants had felt it necessary to raise awareness amongst colleagues in secondary care regarding the amount of planning that may be required to ensure a positive health outcome. One example of this is the consequent impact of cancelled appointments:

“it was cancelled, the first time round, we was so disappointed, just because of the amount of planning that went into this to ensure a positive experience … they don’t appreciate all the outside work that goes on around it. It did not enter their head all the work that had gone on and the two hours travel time that it takes to get there. …In the end I had to write a letter to the consultant and senior nurse to explain the work that had gone into this referral.” (G14)

Within Wales there is a ‘care bundle/ pathway’ (Bowess, 2014) that should be adhered to when people with intellectual disabilities are admitted to hospital. However, participants reported that sometimes they had to take action to ensure its use:

“They had heard about the care pathway but didn’t have a copy of the documents to hand, I think what worked was I had all the secondary care pathway documents with me and ensured that they looked at them and the fact that they had the training as well worked really well.” (B4)

“I don’t think they had seen these documents before (care bundle documentation), they wouldn’t have asked for them, if I had not shown them” (A1)

Finally, CNLDs identified that they often needed to advocate to ensure that needs were met, and positive outcomes achieved:

“He had the procedure with local anesthetic, and he has severe learning disabilities and didn’t really understand the process. I think if I wasn’t there they would have kept on trying to carry out the procedure, they didn’t seem to listen to his family. I had to tell them to stop as he was so distressed. This was not fair to him.” (B3)

Discussion

Analysis of the incidents discussed by participants clearly identified and a range of barriers that people with intellectual disabilities face when seeking to access secondary healthcare. These included barriers that arose due to communication problems, challenges in relation to assessment of capacity to consent (which can impact provision of interventions), a failure to make reasonable adjustments/accommodations, and problems with coordination both within and between services. These findings reflect concerns that have been noted in other research studies (Heslop et al, 2021; Heslop et al, 2018; Tuffrey-Wijne et al, 2015).

...continuity of relationship enables the development of trust and an awareness of the barriers...What this study adds, however, is insight into how CLDNs work to promote better access to secondary healthcare for those they support through their understanding of individual need, identification of actual and potential barriers to access, and use of interventions to reduce/eliminate such barriers. These interventions appear to occur even where learning disability acute care liaison nurses are in post, because CLDNs can provide support prior to contact with secondary health care services and assist with effective coordination of discharge. Often, CLDNs have long standing relationships with the individuals who they support and their families/carers. This continuity of relationship enables the development of trust and an awareness of the barriers that individuals are likely to experience if they need to access secondary healthcare.

When barriers to healthcare are identified, CLDNs appear to adopt several strategies that may potentially impact the healthcare experience of those they support. They undertake a range of preparatory work that focuses on the individual with intellectual disabilities (e.g., providing accessible information, supporting preadmission visits); on staff who will provide care (e.g., through education); or on the environment of care (e.g., risk assessment and ensuring appropriate levels of support are in place).

Promotion of reasonable adjustments is another key strategy used by CLDNs.Promotion of reasonable adjustments is another key strategy used by CLDNs. Whilst the provision of such adjustments is a legal requirement of the Equality Act 2010, such accommodations are not always made (UK Government, 2013a). CLDNs who participated in this study reported both development of materials such as easy read literature and social stories to ensure that those they support receive information regarding their healthcare in a format they can understand. However, they also reported challenging secondary healthcare services to make adjustments such as improved timing of appointments and use of health communication tools/hospital passports.

...in some situations, it may be the CLDN that has to initiate a best interests discussion.In the UK, the Mental Capacity Act 2005 provides the legal framework within which capacity to make key decisions (e.g., consent to treatment) must be considered. (UK Government, 2013b). Consent starts from the position of presuming capacity, and it is the duty of healthcare professionals to assess capacity to consent where there are concerns that an individual may lack capacity. However, the act also notes that capacity can be impacted by the way in which information is provided. CLDNs providing information that is adapted to the needs of those they support is, therefore, an important intervention. Furthermore, if an individual is deemed to lack capacity to make a specific decision, then a ‘best interests’ decision may need to be made. The findings of this study revealed that, in some situations, it may be the CLDN that has to initiate a best interests discussion. This may reflect a lack of understanding of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 by healthcare professionals. This is evidence that CLDNs are making a key intervention; without either valid consent or a best interests decision treatment may be withheld and thus the individual denied care.

Such interventions in relation to consent and capacity are part of a wider intervention adopted by CLDNs, namely the advocacy function they perform to ensure appropriate access to healthcare. This may be advocating for a particular healthcare intervention to take place or, as was the case in one incident reported above, to stop an intervention where it is causing unacceptable distress to an individual.

Given the complex health needs of many people with intellectual disabilities, and the levels of multimorbidity they experience (Hermans & Evenhuis, 2014), they often see a range of healthcare specialists. This can present challenges to coordination of care because individuals with intellectual disabilities may depend on others to transfer information between professionals and settings. If key information is not transferred, there can be delays, a breakdown in care pathways, and in the provision of treatment for one condition that negatively impacts another. CLDN participants in this study reported how they often act as a constant over both time and settings and thus perform a coordinating function.

...many barriers to healthcare experienced by individuals with intellectual disabilities are not an inevitable consequence of having an intellectual disability.A medical model of disability argues that difficulties and barriers arise due to the needs of the individual who is considered disabled and therefore the focus for intervention is on changing the individual. In contrast, the social model of disability asserts that those with impairments are disabled by a range of social, physical, environmental, and economic barriers that prevent their full participation in society (Northway, 1998). As can be seen from the findings of this study, many barriers to healthcare experienced by individuals with intellectual disabilities are not an inevitable consequence of having an intellectual disability. Instead, they arise from a failure to identify and address their needs, and to adapt service provision. Therefore, the social model of disability has great relevance when seeking to reduce health disparities.

Historically, learning disability nurses have been criticised for working within a medical model of care (Mitchell, 2003). It has been reported that there is confusion regarding the role of the CLDN in addressing health needs within the social model of disability (Scottish Government, 2012). This research, however, has identified several ways in which CLDNs identify barriers to secondary care for people with intellectual disabilities and deploy strategies that are aimed to reduce or eliminate such barriers. Whilst, therefore, they did not explicitly articulate that they work within a social model of disability, their practice suggests that this is the case and provides some clarity as to how they address health needs within the social model.

Conclusion and Recommendations

It is recognised that this research was undertaken with a small number of participants in one country and that therefore the findings may not be generalisable to other settings. However, the aim was not to generalise, but instead to explore and provide the basis for future research. From our findings, we can conclude that the CLDN participants in this study play an important role to promote access to secondary healthcare for people with intellectual disabilities. They identify barriers and use strategies to reduce or eliminate them. As such they are working within a social model of disability. Our findings have identified a range of interventions that can be used to support access, and these might usefully be adopted elsewhere. Future research should focus on the extent to which these strategies are utilised in and describing the impact that they have.

Many of these strategies are transferable to care provided in other countries.It is also recognised that the role of the CLDN may not be present in other countries. Nonetheless, we feel that the findings of this study may have relevance since they highlight how CLDNs and all nurses can promote improved access to secondary healthcare for people with intellectual disabilities. Many of these strategies are transferable to care provided in other countries. In addition, practicing within the social model of disability is achievable by all nurses and would promote greater recognition of barriers to healthcare and action to address these.

Authors

Stacey Rees, PhD, MSc, BSc (hons), RN(LD)

Email: stacey.rees@southwales.ac.uk

ORCID ID: 0000-0001-9130-4509

Dr Stacey Rees currently works as a lecturer and researcher at the School of Care Sciences, University of South Wales. Prior to this, she worked as a community learning disability nurse supporting access to healthcare. The research presented here comprises part of her PhD dissertation research.

Ruth Northway, PhD, MSc(Econ), RN(LD)

Email: ruth.northway@southwales.ac.uk

ORCID ID: 0000-0001-8420-733X

Professor Ruth Northway is a Professor of Learning Disability Nursing at the School of Care Sciences, University of South Wales Professor Northway is a Fellow of the Royal College of Nursing and the Learned Society of Wales. Her current role encompasses research and nurse education and acted as Director of Studies for the PhD research presented in this paper. She has previously been a course leader for community nursing courses and prior to working in nurse education was a community learning disability nurse.

References

Barr, O. (2006). The evolving role of community nurses for people with learning disabilities: changes over an 11-year period. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 15(1), 72-82. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01254.x

Boarder, J. (2002). The perceptions of experienced community learning disability nurses of their roles and ways of working: An exploratory study. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 6, 281-296. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469004702006003084

Bowness, B. (2014). Improving general care of patients who have a learning disability. http://www.1000livesplus.wales.nhs.uk/sitesplus/documents/1011/How%20to%20%2822%29%20Learning%20Disabilites%20Care%20Bundle%20web.pdf

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Flanagan, J. C. (1954). The critical incident technique. Psychological Bulletin 51(4), 327–58.

Hemm, C., Dagnan, D., & Meyer, T. D. (2015). Identifying training needs for mainstream healthcare professionals, to prepare them for working with individuals with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 28, 98-110. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12117

Hermans, H., & Evenhuis, H. M. (2014). Multimorbidity in older adults with intellectual disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 35, 776-783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2014.01.022

Heslop, P., Byrne, V., Calkin, R., Pollard, J., & Sullivan, B. (2021). The learning disabilities mortality review (LeDeR) Programme; Annual report 2020. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/LeDeR-bristol-annual-report-2020.pdf

Heslop, P., Read, S., & Stirton, F. D. (2018). The hospital provision of reasonable adjustments for people with learning disabilities: Findings from Freedom of Information requests. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 46, 258-267. https://doi.org/10.1111/bld.12244

Kemppainen, J. K. (2000). The critical incident technique and nursing care quality research. Journal of Advanced Nursing 32(5), 1264-1271. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01597.x

Mafuba, K., Gates, B., & Cozens, M. (2018). Community intellectual disability nurses’ public health roles in the United Kingdom: An exploratory documentary analysis. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 22(1), 61-73. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629516678524

McCormick, F., Marsh, L., Taggart, L., & Brown, M. (2020). Experiences of adults with intellectual disabilities accessing acute hospital services: A systematic review of the international evidence. Health and Social Care in the Community, 29, 1222-1232. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13253

McMahon, M., & Hatton, C. (2020). A comparison of the prevalence of health problems among adults with and without intellectual disabilities: A total administrative population study. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 34, 316-325. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12785

Mitchell, D. (2003). A chapter in the history of nurse education: Learning disability nursing and the Jay Report. Nurse Education Today, 23, 350-356. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0260-6917(03)00025-x

Mobbs, C., Hadley, S., Wittering, R., & Bailey, N. (2002). An exploration of the role of the community nurse, learning disability, in England. British Journal of Learning Disabilities 30 (1), 13-18. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1468-3156.2002.00150.x

Northway, R. (1998). Disability and oppression: Some implications for nurses and nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 26, 736-743. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.00727.x

Nursing and Midwifery Council. (2018). Standards of proficiency for registered nurses. https://www.nmc.org.uk/standards/standards-for-nurses/standards-of-proficiency-for-registered-nurses/

O’Leary, L., Cooper, S. A., & Hughes-McCormack, L. (2018). Early death and causes of death of people with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 31 (3) 325-342. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12417

Rees, S. (2021). Do Community Learning Disability Nurses (CLDNs) support adults with learning disabilities in Wales to access secondary healthcare: An exploratory study within the social model of disability [Doctoral thesis]. University of South Wales: Pontypridd.

Scottish Government. (2012, April 5). Strengthening the commitment: The report of the UK modernising learning disabilities nursing review. https://www.gov.scot/publications/strengthening-commitment-report-uk-modernising-learning-disabilities-nursing-review/documents/

Spassiani, N. A., Chacra, M. S. A., Selick, A., Durbin, J., & Lunsky, Y. (2020). Emergency department nurses’ knowledge, skills and comfort related to caring for patients with intellectual disabilities. International Emergency Nursing, 50,10085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ienj.2020.100851

Tuffrey-Wijne, I., Goulding, L. Giatras, N., Abraham, E., Gillard, S., White, S., Edwards, C., & Hollins, S. (2015). The barriers to and enablers of providing reasonably adjusted health services to people with intellectual disabilities in acute hospitals: Evidence from a mixed methods study. BMJ Open, 4:e004606. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004606

United Kingdom Government. (2013a). Equality Act 2010: Guidance Equality Act 2010: Guidance. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/equality-act-2010-guidance

United Kingdom Government. (2013b). Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice. Code of practice giving guidance for decisions made under the Mental Capacity Act 2005. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/mental-capacity-act-code-of-practice

[

[