Since the Physician Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment (POLST) Paradigm began in 1991, POLST has become utilized throughout the United States. POLST includes the national POLST Paradigm as well as state and regional programs and their specific POLST orders. Yet many nurses may not have received the education needed for POLST implementation. This article seeks to honor individual preferences through advance care planning (ACP) by providing an understanding of POLST, which documents individual treatment wishes as medical orders. In the article the authors discuss advance care planning, advance directives, changes in patient status, and the inception and description of POLST. They distinguish POLST from DNR orders, compare POLST to advance directives, and describe the roles of registered and advanced practice nurses. Additionally, they consider studies that have endorsed the POLST paradigm, and share POLST paradigm pearls as well as possible paradigm pitfalls.

Key Words: Advance Care Planning (ACP), Physician Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment (POLST), medical treatment orders, resuscitation, natural death, advance directives, DNR

Many individuals facing serious illness have vast options available to sustain life...Nurses, including advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs), have the opportunity as well as an essential role to support and honor individual wishes for medical care and treatment through attention to Advance Care Planning (ACP) and when appropriate, Physician Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment (POLST; American Nurses Association [ANA], 2016; Hospice & Palliative Nurses Association, 2017). Many individuals facing serious illness have vast options available to sustain life without having an understanding of the risks, benefits, burdens, and expected outcomes of these technologies and treatments. These same individuals likely have not had any conversations about future health conditions, goals of care, or uncertain medical outcomes, and thus may receive treatment that is unwanted (Institute of Medicine, 2015). The last step of the ACP process is POLST (National POLST Paradigm, 2018c). The goal of this article is to promote nurse support of individual preferences through ACP via a thorough understanding and utilization of POLST, which documents individual treatment wishes as medical orders.

Advance Care Planning

Advance care planning is a process which supports adults, at any age or health status, as they reflect and record personal values, life goals, and preferences regarding future healthcare and treatment (Kass-Bartelmes & Hughes, 2003; Sudore et al., 2017). For individuals with serious or chronic illness, the goal of ACP is to ensure that care and treatment is consistent with their goals and preferences, as well as to name a healthcare surrogate (Hickman, Hommes, Moss, & Tolle, 2005, Hickman, Sabatino, Moss, & Nester, 2008). The first step in ACP is talking about what matters most to an individual.

For individuals with serious or chronic illness, the goal of ACP is to ensure that care and treatment is consistent with their goals and preferences...Advance care planning conversations can take place in the home or in other settings (Racusin, 2017). Some ACP conversations can be brief, as individuals have already determined their preferences. Other conversations require more time or additional meetings. In an ideal world, preferences would be discussed and documented before events occur and require a healthcare professional or first responders to make decisions about appropriate actions. Prior conversations between healthcare professionals, individuals, and families are important when making treatment decisions on behalf of an individual, if documentation is lacking (Sabatino, 2010). Conversations over time give more meaning and context to individual wishes.

The role of the surrogate is critical to communicate the wishes and preferences of the individual...Healthcare professionals should be educated about and mindful of individual and family cultural preferences and diversity for each patient when facilitating ACP conversations. At times, someone speaking on behalf of an individual may have their own thoughts about what treatment preferences they would want for this person, instead of representing the person’s actual wishes (Hall & Jenson, 2014). The role of the surrogate is critical to communicate the wishes and preferences of the individual, or in effect, to be the voice of that individual. The ACP process documents an individual’s future healthcare preferences and names his or her chosen surrogate in an advance directive.

What is an Advance Directive?

Most advance directives include general healthcare preferences for future situations.The advance directive is usually the first document in the ACP process and is best completed when an individual reaches adulthood. Most advance directives include general healthcare preferences for future situations. Individuals can also name a healthcare surrogate to guide treatment decisions if they are unable to speak for themselves (Detering & Silveira, 2018). As healthcare changes occur, ongoing ACP conversations are important, and the advance directive may need to be updated.

Advance directives are often stored in secure locations, such as a locked drawer or safe deposit box. Unfortunately, this document may not be available when an individual becomes seriously ill or is in an accident (National POLST Paradigm, 2019d). Everyone should be encouraged to share their advance directive with their surrogate, family, and physician, and have a copy of the advance directive in their medical record.

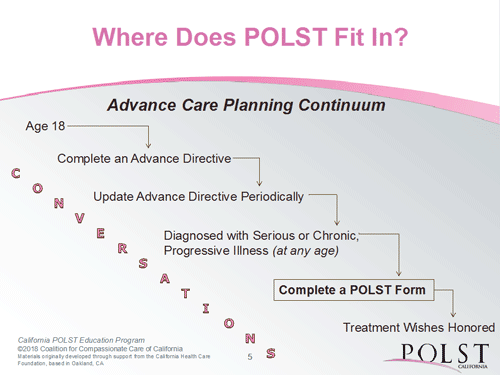

...POLST conversations clarify and formally document individual wishes into a current medical order setWhile the advance directive details general healthcare instructions for future medical emergencies, POLST conversations clarify and formally document individual wishes into a current medical order set (National Institute on Aging, 2018; National POLST Paradigm, 2019d). For someone with serious illness at any age, a POLST discussion often follows completion of the advance directive (Dahlin, 2014). Conversations continue to be important throughout the ACP process as advance directives and POLST are completed and updated. (See Figure 1).

Figure 1. Where Does POLST Fit In?

(Coalition for Compassionate Care of California [CCCC], 2018b)

Changes in Medical Status

A “No, I would not be surprised” response should serve as a trigger for a nurse to have an ACP discussion...As people age, when illness(es) progress, or when a new illness arises, individuals may become more fragile and less resilient. During serious illness or a significant change in medical status, an individual’s ability to recover may be impaired, and unfortunately, he or she may never return to the prior baseline (Barker & Scherer, 2016; Kelley et al., 2017). Within our scope of practice, nurses can and should address changes in an individual’s health condition as well as asking ourselves the surprise question, namely: “Would I be surprised if the individual died within the next year? “ (Murray & Boyd, 2011; Weissman & Meier, 2011). A “No, I would not be surprised” response should serve as a trigger for a nurse to have an ACP discussion with the individual and/or family (Meier & Beresford, 2009; Moss et al. 2008; Moss et al., 2010). This is an appropriate time to start or continue talking with patients and families.

Although nurses do not determine prognoses, we may see signs of decline earlier than some providers, and thus nurses should take timely action. Nurses are allowed and encouraged, within the scope of nursing practice, to provide individuals and families with educational materials related to decline in status without inferring a prognosis. Two examples of classic patient education booklets are Hard Choices for Loving People (Dunn, 2017) and Gone From My Sight (Karnes, 1986). Asking an individual and/or family about changes in such areas as functional level, loss of weight, or fatigue or weakness often offers insight into increasing decline or frailty. Patient awareness and education may precede POLST.

Inception of POLST in the Advance Care Planning Process

Every state is now recognized and has a program designation from the National POLST Paradigm.In 1991, medical ethicists at Oregon Health and Science University determined that preferences for end-of-life care were not consistently honored (Dunn et al., 1996; National POLST Paradigm, 2019a & 2019f). Based on this observation, this group developed a new tool to honor individual wishes for end-of-life treatment (National POLST Paradigm, 2019a & 2019f). The original program became known as POLST. Over time, the program evolved as the National POLST Paradigm with a vision for all states to adopt the consistent process, resulting in improved individual care and greater individual control and direction over personal medical treatment. The mission statement of this organization is to “Advance the POLST Paradigm through stewardship, education, advocacy, support for state efforts, and national leadership” (National POLST Paradigm, 2019h, para #2). The POLST national website (National POLST Paradigm, 2019j) provides a map with current state activities and program status. Every state is now recognized and has a program designation from the National POLST Paradigm.

What is POLST?

POLST is an approach to improve care during serious illness and ensure that individuals receive the treatment they desire. When a healthcare professional considers the surprise question, a “no” answer is an indication that it is appropriate to implement POLST conversations (National POLST Paradigm, 2018b). The surprise question is a powerful tool to determine with whom to discuss POLST. As an integral part of ACP, POLST begins with conversations between a person with chronic or serious illness or frailty, a healthcare professional, and family members and/or significant others.

A commonly missed opportunity after ACP conversations is the failure to translate stated wishes into actual medical ordersA commonly missed opportunity after ACP conversations is the failure to translate stated wishes into actual medical orders (Dahlin, 2014). It is critical to understand that an advance directive is not a medical order. The POLST is an actionable order used in medical emergencies (Jesus et al., 2014; National POLST Paradigm, 2019f). It is an ACP tool designed to provide medical orders for individuals who are frail and/or seriously ill.

It is necessary for patients, surrogates, and healthcare professionals to understand and complete the POLST form itself to honor patient wishes. Table 1 describes the elements of the National POLST Paradigm needed to assure that an individual is informed; understands his or her health status; and has had opportunities to make personal choices about known medical interventions. Specifically included are treatment options, surrogate and decision-making terminology, and other elements to clarify the standards in the POLST Paradigm model. Best practice for POLST-appropriate individuals occurs when nurses and other healthcare providers incorporate the POLST Paradigm into patient care (See Table 1, which was developed by the authors).

Table 1. Elements of the POLST Paradigm and POLST Form

|

Element |

Description |

|

Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR); also known as Full Code |

Attempt resuscitation and full treatment measures. |

|

Capacity for Medical Decision Making |

The ability to understand the illness and treatment options in order for an individual to make informed choices (Karlawish, 2017; Bomba, n.d.). |

|

Comfort Measures Only Goals / Comfort-Focused Treatment |

Goals change from treating disease(s) to maximizing comfort and quality of life by lessening burden; and minimizing and treating pain, suffering, distress, and symptoms. This shift in focus is often evident near the end-of-life (The Joint Commission, 2014; Zanartu & Matti-Orozco, 2013). |

|

Decision-Maker |

See Surrogate. |

|

Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) / Do Not Attempt Resuscitation (DNAR) / Allow Natural Death (AND) |

Does not mean “do not treat.” The DNR/DNAR/AND is a separate section on the POLST form and can be chosen with any level of disease or treatment in the medical interventions section (Breault, 2011; Chen & Daidre, 2017; Plakovic, 2016; Venneman, 2008). |

|

Full Code |

See Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. |

|

Full Treatment Goals |

Use of all appropriate medical or surgical treatments which could possibly be effective, including intubation, ventilator (i.e., artificial life support) and other interventions (LeBlanc, 2018). |

|

Limited Treatment or Selective Treatment |

Providing interventions to treat new or reversible illness/injury or other chronic conditions, while avoiding or limiting invasive or burdensome interventions (LeBlanc, 2018). |

|

Medical Frailty |

A clinical syndrome in the elderly with the loss of physical or cognitive reserves, including 3 or more of the following: unintentional weight loss, self-reported fatigue, weakness, slow walking speed, or decreased activity. Individuals with frailty may be less tolerant and/or not as responsive to medical interventions and may have difficulty recovering from illness or hospitalization (Xue, 2011; Walston, 2019). |

|

National POLST Paradigm |

The accepted standard of discussing and documenting individual treatment choices in preparation for an emergency situation. (National POLST Paradigm, 2014 & 2019f). |

|

POLST Form |

A standardized set of medical orders promoted by the National POLST Paradigm which may vary by name or content from state to state (National POLST Paradigm, 2019b, 2018a, & 2019e). |

|

POLST Program Designation |

The National POLST level of compliance as followed in each state, based on the National POLST paradigm: developing, endorsed, mature, or non-conforming (National POLST Paradigm, 2018c). |

|

Surrogate |

The person designated by an individual to make healthcare decisions when the individual is unable to do so. Also known as a healthcare agent, healthcare proxy, healthcare power of attorney or decision-maker. This person may be a family member or a trusted person (National POLST Paradigm, 2017). |

Knowing an individual’s POLST preferences guides care during serious illness or near the end-of-life. Understanding and utilizing elements of the POLST Paradigm during care for seriously ill or frail individuals supports appropriate initiation of ACP with interventions that are consistent with an individual’s health status. The benefit of actionable medical orders via a completed POLST form is to ensure that an individual’s wishes are honored, either when emergency medical services are called or when the individual transfers to a different care facility and emergent care is required. Knowing an individual’s POLST preferences guides care during serious illness or near the end-of-life. The next section offers additional information to compare POLST to DNR orders and advance directives to further clarify important concepts.

POLST Distinction from DNR Order

An important concept to understand and share with others is that a status of "Do Not Attempt Resuscitation (DNAR or DNR) / Allow Natural Death (AND)" does not mean "do not treat." POLST orders identify not only resuscitation preferences but also provide additional medical treatment directions when an individual is in a medical crisis but breathing or has a pulse (i.e., the person is alive and CPR is not indicated). If the individual is seriously ill, POLST gives clarity as to the type of treatment desired (Pedraza, Culp, Falkenstine, & Moss, 2016). An individual may request a DNR status and still want full treatment with all appropriate medical interventions, with the exception of CPR. If the patient’s condition indicates CPR and the POLST form designates DNR, emergency medical services follow the individual's preferences for DNR and allow a natural death.

Not all states have sanctioned stand-alone out-of-hospital or pre-hospital DNR forms, although patients receiving hospice care may have DNR orders with the hospice program. POLST provides actionable medical orders to indicate Attempt CPR or DNR outside of the hospital, in home and community settings (Glatter & Mirarchi, 2015; Lachman, 2010; Schmidt, Ziye, Fromme, Cook, & Tolle 2014). Because ACP discussions may include choices regarding code status, nurses should be aware of similarities and differences between POLST and advance directives.

Comparison of POLST to Advance Directives

POLST forms and advance directives have some similarities and should complement each otherPOLST forms and advance directives have some similarities and should complement each other (see Table 2, also developed by the authors). As with an advance directive, the original POLST form stays with an individual, and copies are legally valid. The healthcare professional ascertains that both the advance directive and the POLST form are scanned into the electronic medical record (EMR) or placed in a paper chart at the care setting. When the patient is at home, the original should be readily available in a prominent place. Healthcare staff and the patient are responsible for ensuring that the POLST form travels with the patient during any transfer because, unlike an advance directive, the POLST is a medical order (National POLST Paradigm, 2014, 2017). The POLST form should be reviewed periodically and a new POLST considered when:

- There is a substantial change in an individual’s health status;

- The person is transferred between care settings or changed to another level of care; or

- The individual’s treatment preferences change.

When a new POLST is signed, the previous POLST form is voided by writing VOID across the form with a signature and date (National POLST Paradigm, 2017). Both the new and voided POLST forms are placed in the medical record.

Table 2. Comparison of Advance Directive and POLST Form

|

Item |

Advance Directive |

POLST Paradigm Forms |

|

Population |

All adults >18 years old. |

Any age, with chronic illness, serious illness, medical frailty, and/or nearing end-of-life. |

|

Timeframe |

Addresses future care/future medical conditions. |

Addresses current treatment wishes/current medical status. |

|

Purpose of each document |

For directing end-of-life wishes via a legal document, expressing values, and/or appointing a surrogate. |

Communicates individual treatment preferences by creating an actionable medical order. |

|

When does it go into effect? |

When the individual cannot speak for themselves, usually at the end-of-life, with certain stipulations and circumstances. |

An immediately actionable medical order once signed by a provider. |

|

Where completed? |

Any setting, not necessarily in a healthcare setting; may be created in a lawyer’s office. |

Any setting, with a conversation with a healthcare professional. |

|

Who completes the form? |

Individual with assistance of healthcare professionals or a lawyer. |

The healthcare professional fills out the form and must sign it. In the majority of states, individuals (or their surrogate) must sign for the form to be valid. It should be completed only after an ACP conversation. |

|

Resulting product |

Surrogate appointed and/or statement of preferences. |

Medical orders based on informed, collaborative decision making. |

|

Surrogate role |

Cannot fill out the Advance Directives form (advance directives cannot be completed if the individual lacks capacity). |

Can consent or decline treatment options, if individual lacks capacity. However, the surrogate cannot change the original/current POLST unless there is significant change in the individual’s condition and discussion with healthcare professional. If current POLST is changed, a new form would then be completed. |

|

Are the individual’s wishes known? |

Maybe; usually described in general statements. |

Yes, individual treatment wishes are stated on the POLST order. |

|

Emergency Medical Services (EMS) role |

Does not direct EMS. |

Directs EMS as a medical order. |

|

Portability |

Individual/family responsibility. |

From home, individual/family brings the POLST form. The original POLST form stays with the individual. Copies and movement of the original POLST form is a shared responsibility of the healthcare professional and individual. |

|

Periodic review |

Individual/family responsibility. |

Healthcare professional responsibility during change of condition or location of individual. An individual may review, change or void the POLST form at any time. |

|

Location of document |

Original stays with the individual; ideally, entered in Electronic Medical Record (EMR) and the surrogate has a copy. |

Original stays and travels with an individual; copies entered in EMR and ideally, surrogate has a copy. When a state registry exists, POLST is available via the registry. |

(National POLST Paradigm, 2013, 2017)

Role of the Nurse

Nursing has been ranked by the public as the most trusted profession for the past sixteen years (American Hospital Association, 2018). Nurses have the responsibility to advocate for individuals and families across every setting and at all stages of life (ANA, 2016). All nurses are within their scope of practice to promote ACP conversations for individuals with serious illness and/or the medically frail.

Nurses can bring more support, comfort, and peace to individuals and families with purposeful ACP, including POLST conversations (Izumi, 2017; National Institute on Aging, 2018; Rathke & Hickman, 2017). Nurses should have knowledge, skill, and understanding about the process of ACP, advance directives, and POLST in order to facilitate compassionate and competent discussions with individuals (Cantillo, Corliss, Kimata, Chieko, & Ruiz, 2017; Bomba, Kemp & Black, 2012; National POLST Paradigm, 2018a). Accurate terminology will enable nurses to articulate relevant aspects of POLST (e.g., POLST paradigm, programs, forms (National POLST Paradigm, 2018a). All healthcare professionals involved in ACP discussions, including physicians/providers, nurses, social workers, and chaplains who are trained and skilled in the facilitation of the POLST paradigm, can participate in the conversations and, if appropriate, the preparation of the POLST form (Briggs, Hammes & Anderson, 2015). Shared healthcare decision making with individuals, family members, healthcare professionals and nurses is an integral part of the ACP process, including POLST. Nurses should speak about an individual’s wishes, even if family or other healthcare professionals view it differently.

The ANA Position Statement (2016), Nurses’ Roles and Responsibilities in Providing Care and Support at the End-of-Life, states that engaging individuals and families in ACP conversations is a nursing responsibility. Nurses should ensure that individuals and families have current and accurate information about risks, benefits, burdens, and expected outcomes of both treatment choices and potential illness trajectories. Discussions should include advocacy on an individual’s behalf for ongoing conversations with providers and other colleagues.

Nurses are professionally responsible and encouraged to complete POLST training.Nurses are professionally responsible and encouraged to complete POLST training. Examples of such training in a continuing education format are, Programs in Your State (National POLST Paradigm, 2019c); Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association (HPNA) eLearning, POLST Education for Healthcare Professionals (Joyner, 2014); Working with POLST for Professionals (Coalition for Compassionate Care of California, 2018c); and others. Training should be completed before introducing POLST to individuals and families. Some individuals or families may decline to participate in the conversation or decline to select treatment choices. The nurse should assure their understanding that, by not designating choices, the default standard of care will be full treatment, including resuscitation (Nairn, 2013). By default, not making a choice designates full code and full treatment.

Role of the Advanced Practice Registered Nurse

In both primary and specialty care, ACP conversations are an essential requirement for advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) who work with individuals with serious illness or medical frailty (Kates, 2017; Miller, 2017; Schlenk, 1997). All APRNs should be knowledgeable about the POLST paradigm and the nurse role (Hayes, 2016; Hayes, Zive, Ferrell, & Tolle, 2017). Some APRNs have the authority to sign the POLST form as a medical order, based on state laws and state nurse practice acts and rules (Androus, 2017). The National POLST Paradigm recommends that physicians, APRNs, and physician assistants be authorized to initiate and sign POLST forms (National POLST Paradigm, 2016). This authorization would increase the completion of POLST in many settings.

Validation by the APRN of an informed, collaborative conversation with shared decision making should precede signing of the POLST form.Advanced practice registered nurses are accountable for their medical orders, including the POLST form (American Medical Association, 2017; National Council of State Boards of Nursing, 2018). POLST is not simply signing a form (Mirarchi et al., 2015). Validation by the APRN of an informed, collaborative conversation with shared decision making should precede signing of the POLST form. Medical errors and incomplete POLST forms could occur if the APRN signs the form without affirming prior discussions and the accuracy of an individual’s stated choices. The purpose of the POLST form is to translate patient wishes into actionable medical orders that provide direction for emergency care for an individual in any setting. The APRN is one of several healthcare professionals who utilize the POLST Paradigm and disseminate POLST information and education nationally.

Endorsing the POLST Paradigm

Numerous studies have supported the POLST paradigmNumerous studies have supported the POLST paradigm (National POLST Paradigm, 2019i). A frequently cited study by Fromme, Zive, Schmidt, Cook, and Tolle (2014) substantiated that the POLST form is an effective tool to provide orders that ensure an individual’s wishes are honored. According to this study, most individuals preferred to die at home. Compared to those requesting full treatment, those who died with POLST orders of Comfort Measures Only were significantly less likely to die in the hospital. This study demonstrated the impact of POLST as a component of a comprehensive ACP process.

POLST Paradigm Pearls

Several criteria are a part of the POLST process and subsequent orders. The ideal POLST paradigm includes the following (National POLST Paradigm, 2017, 2018a):

- Early ACP discussions with individuals, healthcare professionals and families;

- Prompt recognition of individuals who are appropriate for a POLST conversation;

- Consistency of the POLST process, resulting in desired outcomes for individuals;

- Voluntary completion of a POLST form;

- POLST orders that represent an individual’s treatment preferences for care during medical emergencies;

- Signature of the POLST order by the provider after validation of individual treatment wishes;

- Availability of the POLST orders to emergency medical services as well as to all treating providers who will participate in ongoing care; and

- Transfer of the POLST order with an individual when transitioning from one care setting to another.

Possible POLST Paradigm Pitfalls

Every process, including the POLST Paradigm, has the opportunity for concerns. Without a comprehensive POLST Paradigm, some of the following situations may occur (Sabatino, 2018):

- Individuals may feel pressured to complete a POLST (e.g., to comply with an agency policy mandating POLST), which violates their autonomy and legal rights to make healthcare decisions. Individuals may also feel uncomfortable with treatment decisions on their POLST form;

- Unnecessary or unwanted transfers to the Emergency Department may occur;

- Providers may become confused when a POLST form has been modified (e.g., cross-outs, dates, circles, initials);

- POLST orders may not accurately express an individual’s treatment wishes if conversations were not comprehensive;

- Treatment may or may not be given other than as desired by an individual;

- The POLST form is not available or is not transported with an individual;

- The POLST form is insufficiently completed; and/or

- Individual identifiers or signature dates are inaccurate or absent.

Fundamentals of a comprehensive POLST Paradigm focus on informed conversations between individuals and their healthcare professional(s). These discussions include individual goals, wishes, and preferences for treatment if a crisis were to occur. POLST discussions include risks, benefits, burdens, and potential outcomes of life-sustaining treatment options. The goal of this collaborative, voluntary, actionable medical order is to honor patient wishes.

Conclusion

Nurses have an essential role in the ACP process to engage in conversations with individuals who are frail or seriously ill, and when appropriate, having informed and collaborative conversations about POLST. These rich discussions focus on individual values and wishes, leading to decisions about medical treatments, which are honored across the healthcare continuum (Morrison & Meier,2004; Quill, 2000; Quill & Abernathy, 2013, Sudore et al., 2017). The POLST form does not replace the advance directive and is always voluntary. It is not a form for individuals to complete without their healthcare provider, as POLST involves shared decision making.

Nurses who initiate or participate in this process will experience the fulfillment of knowing that individuals...have their choices honored.Nurses can honor an individual’s wishes by incorporating the three Cs of the POLST process: Caring conversations, Consistent form, and Comprehensive education of healthcare professionals (Coalition for Compassionate Care of California, 2018a). Knowledge about ACP and POLST can empower nurses as patient advocates to engage in conversations with individuals, families, and other healthcare professionals. Nurses who initiate or participate in this process will experience the fulfillment of knowing that individuals receive the treatment and care they want, do not receive unwanted treatment, and have their choices honored.

Authors

Nancy Joyner, MS, CNS-BC, APRN, ACHPN®

Email: njoyner@nancyjoyner.com

Nancy Joyner is a nationally recognized author, consultant, speaker, and educator. She holds a BA degree in biology and pre-medicine and is nationally certified through the Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association. Nancy is a self-employed Palliative Care Clinical Nurse Specialist who has gained extensive experience in serious illness, frailty, and end of life care through her 28 years of working as a bedside nurse plus her 12 years as an advanced practice nurse. Nancy is the subject matter expert for palliative care for the University of North Dakota Center for Rural Health Rural Community-Based Palliative Care project. She is an approved educator for the Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association, a certified First Steps Facilitator Instructor, and a California-trained POLST trainer who has written and published locally on the topic of advance care planning and POLST. Nancy is a member of the National POLST Paradigm Education Committee and is North Dakota’s POLST Program Coordinator.

Carol Palmer, RN, MS

Email: carolpalmerrn@icloud.com

Carol Palmer has devoted her 55-year career as a nurse to serving dying individuals and families in homes and in-patient hospice and long term care settings. She created a home health agency in Bend, Oregon, in 1984, and later worked for both Hospice of Bend and Hospice of Redmond & Sisters, after earning Certified Registered Nurse Hospice (CRNH) and Certified Hospice and Palliative Nurse (CHPN) certification. She was the point person for Hospice of Redmond & Sisters in obtaining JCAHO Accreditation. Carol was a hospice nurse when use of the POLST form was initiated in Oregon and witnessed its positive impact on care provided by nurses, emergency personnel and first responders. Carol earned an MS in counseling from Oregon State University. She continues her commitment to end of life care through bereavement support and remains committed to “a good death” through providing compassionate, informed care, including advance care planning and POLST.

Joanne Hatchett, MS, FNP-BC, APRN, ACHPN®

Email: jmhatch74@gmail.com

Joanne Hatchett has worked as a family nurse practitioner in the Woodland Clinic Medical Group in Sacramento, CA since 1995, caring for adult and geriatric patients. Since 2004, she served as the Palliative Care Coordinator for Woodland Memorial Hospital and developed the Bridge Program for Palliative and Supportive Care serving patients throughout Yolo County. Joanne is the lead developer of the California POLST Education Program Curriculum. Additionally, she has taught 27 POLST Train the Trainer Programs throughout California to nearly 1,000 participants, and has given many other POLST and palliative care presentations. She graduated from San Francisco State University with a BSN, and received both an MSN as a Cardiopulmonary Clinical Nurse Specialist and a Family Nurse Practitioner Post-Master’s certification from the University of California, San Francisco. Additionally, she is an Advanced Certified Hospice and Palliative Care Nurse. In 2013, Joanne was recognized by the Coalition for Compassionate Care of California with the first Compassionate Care Innovator Award.

References

American Hospital Association. (2018, Jan 10). Nurse watch: Nurses again top Gallup Poll of trusted professions and other nurse news. Retrieved from: https://www.aha.org/news/insights-and-analysis/2018-01-10-nurse-watch-nurses-again-top-gallup-poll-trusted-professions

American Medical Association. (2017). State law chart: Nurse practitioner practice authority. Retrieved from: https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/ama-assn.org/files/corp/media-browser/specialty%20group/arc/ama-chart-np-practice-authority.pdf

American Nurses Association. (2016). Position statement: Registered nurses’ roles and responsibilities in providing expert care and counseling at the end of life. Retrieved from: https://www.nursingworld.org/~4af078/globalassets/docs/ana/ethics/endoflife-positionstatement.pdf

Androus, A. B. (2017). Can a nurse practitioner sign advance directives or POLST forms? Retrieved from: https://www.registerednursing.org/answers/nurse-practitioner-sign-advanced-directives- polst-forms/

Barker, P. C., & Scherer, S. (2016). Fast facts and concepts #326. Illness trajectories: Description and clinical use. Retrieved from: https://www.mypcnow.org/copy-of-fast-fact-325

Bomba, P. (n.d.) Capactity determination: Training professionals to comply with Family Health Care Decisions Act (FHCDA). Retrieved from: https://slideplayer.com/slide/1405131/

Bomba, P., Kemp, M., & Black, J. (2012). POLST: An improvement over traditional advance directives. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, 79(7), 457-64. doi:10.3949/ccjm.79a.11098

Breault, J. L. (2011). DNR, DNAR, or AND? Is language important? Ochsner Journal, 11(4), 302-306.

Briggs L., Hammes, B., & Anderson, S. (2015). Respecting choices advance care planning facilitator certification manual: A guide to person-centered conversations. La Crosse, WI: Gundersen Health System.

Cantillo, M., Corliss, A., Kimata, C., Chieko, R. J. & Ruiz, J. (2017). Honoring patient choices with advance care planning. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing, 19(4), 305-311. doi: 10.1097/NJH.0000000000000359

Chen, D., & Daidre, A. (2017). Clarity or confusion? Variability in uses of “allow natural death” in state POLST forms. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 20(7), 695–696. doi:10.1089/jpm.2017.0064

Coalition for Compassionate Care of California. (2018a). California POLST Project (Slide # 47), Section, What is POLST? California POLST Education Program manual, p.47.

Coalition for Compassionate Care of California. (2018b). Where does POLST fit in? With permission, retrieved from: http://polst.org/advance-care-planning/polst-and-advance-directives/

Coalition for Compassionate Care of California. (2018c). Working with POLST for healthcare professionals. Retrieved from: https://csupalliativecare.org/programs/polst/

Dahlin, C. (2014). Advance care planning: It’s not just for end of life. Retrieved from: http://micmrc.org/system/files/Advanced%20Care%20Planning%20C.%20Dahlin%20November%202014.pdf

Detering, K. & Silveira, M. J. (2018). Advance care planning and advance directives. UpToDate. Retrieved from: UpToDate: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/advance-care-planning-and- advance-directives

Dunn, H. (2017). Hard choices for loving people. (6th Ed.). Naples, FL: Quality of Life Publishing.

Dunn, P., Schmidt, T., Carley, M., Donius, M., Weinstein, M., & Dull, V. (1996). A method to communicate patient preferences about medically indicated life-sustaining treatment in the out-of-hospital setting. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 44(7). doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb03734.x

Fromme, E., Zive, D., Schmidt, T., Cook, J., & Tolle, S. (2014). Association between physician orders for life-sustaining treatment for scope of treatment and in-hospital death in Oregon. Journal of the American Geriatric Society, 62(7), 1246-1251. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12889

Glatter, R. & Mirarchi, F. (2015, April 7). POLST and DNR: Misunderstandings that confound critical care. Medscape Internal Medicine, Retrieved from: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/842419

Hall, N. & Jenson, C. (2014). Implementation of a facilitated advance care planning process in an assisted living facility. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing, 16(2), 113-119.

Hayes, S. (2016). OHSU Study: Expanding access to end-of-life treatment planning -YouTube video. https://vimeo.com/188106503

Hayes, S. A., Zive, D., Ferrell, B., & Tolle, S. (2017). The role of advanced practice registered nurses in the completion of physician orders for life-sustaining treatment. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 20(4), 415-419. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2016.0228

Hickman, S. E., Hammes, B. J., Moss, A. H., & Tolle, S. W. (2005). Hope for the future: Achieving the original intent of advance directives. Hastings Center Report, 35(6), S26-S30.

Hickman, S., Sabatino, C., Moss, A. & Nester, J. (2008). The POLST (Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment) paradigm to improve end-of-life care: Potential state legal barriers to implementation. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 36(1), 119-140. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2008.00242.x

Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association (HPNA). (2017). Position statement: Advance care planning. Pittsburg, PA. Retrieved from: https://advancingexpertcare.org/position-statements

Institute of Medicine of the National Academies (IOM). (2015). Dying in America: Improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Izumi, S. (2017). Advance care planning: The nurse's role. American Journal of Nursing, 117(6), 56-61. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000520255.65083.35

Jesus, J. E., Geiderman, J. M., Venkat, A., Limehouse, W. E., Derse, A. R., Larkin, G. L., & Henrichs, C. W. (2014). Physician orders for life-sustaining treatment and emergency medicine: Ethical considerations, legal issues, and emerging trends. (2014). Annals of Emergency Medicine, 61(2), 140-144. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.03.014

Joyner, N. (2014). HPNA0077: HPNA-POLST education for healthcare professionals. Retrieved from: https://www.nurseslearning.com/syllabus.cfm?CourseKey=7274

Karlawish, J. (2017). Assessment of decision-making capacity in adults. UpToDate. Retrieved from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/assessment-of-decision-making-capacity-in-adults

Karnes, B. (1986). Gone from my sight: The dying experience. Vancouver, WA: Barbara Karnes Publishing.

Kass-Bartelmes, B. & Hughes, R. (2003). Advance care planning, preferences for care at the end of life. Research in Action, 12 Retrieved from:https://archive.ahrq.gov/research/findings/factsheets/aging/endliferia/endria.html

Kates, J. (2017). Advance care planning conversations. Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 13(7), e321-e323. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2017.05.011

Kelley, A., Covinsky, K., Gorges, R., McKendrick, K., Bollens-Lund, E., Morrison, R., & Ritchie, C. (2017). Identifying older adults with serious illness: A critical step toward improving the value of health. Health Services Research, 52(1). doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12479

Lachman, V. (2010). Do-not-resuscitate orders: Nurse’s role requires moral courage. Medsurg Nursing, 19(4), 236, 249-526.

LeBlanc, T.W. & Tulsky, J. (2018). Discussing goals of care. Retrieved from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/discussing-goals-of-care

Meier, D., & Beresford, L. (2009). POLST offers next stage in honoring patient preferences. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 12(4), 291-291. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.9648

Miller, B. (2017). Nurses in the know: The history and future of advance directives. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 22(3). doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol22No03PPT57

Mirarchi, F.L., Cammarata, D., Zerkle, S.W., Cooney, T.E., Chenault, J., & Basnak, D. (2015). TRIAD VII: Do prehospital providers understand physician orders for life-sustaining treatment documents? Journal of Patient Safety, 11(1), 9-17. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000164

Morrison, R.S. & Meier, D.E. (2004). Clinical practice. Palliative care. New England Journal of Medicine. 350, 2582-2590. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp035232

Moss, A., Ganjoo, J., Sharma, S., Ganson, J., Senft, S., Weaner, B., Dalton, C., …& Schmidt, R. (2008). Utility of the “surprise” question to identify dialysis patients with high mortality. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 3(5), 1379-1384. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00940208

Moss, A. H., Lunney, J. R., Culp, S., Auber, M., Kurian, S., Rogers, J., Dower, J. & Abraham, J. (2010). Prognostic significance of the “surprise” question in cancer patients. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 13(7), 837-840. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0018

Murray, S. A. & Boyd, K. (2011) Using the ‘surprise question’ can identify people with advanced heart failure and COPD who would benefit from: A palliative care approach. Palliative Medicine London, 25(4), 382. doi: 10.1177/0269216311401949

Nairn, F. T. (2013). POLST: A portable plan for care. Health Progress: Journal of the Catholic Health Association of the United States, 94(6), 87-89.

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2018). APRNs in the U. S. website. Retrieved from: https://www.ncsbn.org/aprn.htm

National Institute on Aging. (2018). Advance care planning: Healthcare directives. National Institute on Aging. Retrieved from: https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/advance-care-planning-healthcare-directives

National POLST Paradigm (POLST). (2013). POLST: What it is and what it is not. Retrieved from: http://polst.org/2013/06/20/polst-what-it-is-and-what-it-is-not/

POLST. (2014). Legislative guide. Retrieved from: https://polst.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/2014.02.20-POLST-Legislative-Guide-FINAL.pdf

POLST. (2016). POLST policy: Support for nurse practitioners and physician assistants signing POLST paradigm forms. Retrieved from: https://polst.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/2016.12-NPPTF-Supports-Nurse-Practitioners-and-Physician-Assistants-Signing-POLST-Paradigm-Forms.pdf

POLST. (2017). The POLST care continuum toolkit. Retrieved http://polst.org/toolkit/

POLST. (2019a). About the national POLST paradigm. Retrieved from: http://polst.org/about-the-national-polst-paradigm/

POLST. (2019b). Elements of the POLST form. Retrieved from: http://polst.org/elements-polst-form/

POLST. (2019c). POLST and advance care planning. Retrieved from: http://polst.org/polst-advance-care-planning/

POLST. (2019d). POLST and advanced directives. Retrieved from: http://www.polst.org/advance-care-planning/polst-and-advance-directives/

POLST. (2018a). POLST conversation & documentation. Retrieved from: http://polst.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/2018.01.31-POLST-Conversation-and-Documentation.pdf

POLST. (2019e). POLST form elements. Retrieved from: http://polst.org/

POLST. (2019f). POLST for professionals. Retrieved from: http://polst.org/professionals-page/

POLST. (2019g). POLST history. Retrieved from: http://polst.org/about-the-national-polst-paradigm/history/

POLST. (2018b). POLST paradigm population: who should have a POLST form? Retrieved from: http://polst.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/2018.01.29-The-POLST-Paradigm-Population-Who-Should-have-a-POLST.pdf

POLST. (2018c). POLST program designation. Retrieved from: http://polst.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/2018.04.11-National-POLST-Program-Designations-Map.pdf

POLST. (2019h). POLST strategic plan. Retrieved from: http://polst.org/strategic-plan/?pro=1

POLST. (2019i). Research publications about POLST: 1998-2018. Retrieved from: http://polst.org/resources/citations/?pro=1POLST

POLST. (2019j). State programs. Retrieved from: http://polst.org/programs-in-your-state/

Pedraza, S., Culp, S., Falkenstine, E., & Moss, A. (2016). POST forms more than advance directives associated with out of hospital death: Insights from: a state registry. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 51(2), 240-246. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.10.003

Plakovic, K. (2016). Burdens versus benefits: When family has to decide how much is too much. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing, 18(5), 382-387. doi: 10.1097/NJH.0000000000000270

Quill, T.E. (2000). Initiating end-of-life discussions with seriously ill patients. Addressing the "elephant in the room". Journal of the American Medical Association, 284(19), 2502-2507. doi:10.1001/jama.284.19.2502

Quill, T.E. & Abernethy, A.P. (2013). Generalist plus specialist palliative care — creating more sustainable model. New England Journal of Medicine, 368, 1173-1175. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1215620

Racusin, E. (2017). Why early advance care planning conversations are so important. Cancerwise, 10. Retrieved from: https://www.mdanderson.org/publications/cancerwise/2017/10/why-early-advance-care-planning-conversations-are-so-important.html

Rathke, K. & Hickman, S. (2017). Indiana physician orders for scope of treatment (POST): Implications for nurses. Indiana State Nurses Association Bulletin. Retrieved from: http://www.nursingald.com/uploads/publication/pdf/1464/Indiana_Bulletin_2_17.pdf

Sabatino, C. (2010). The evolution of health care advance planning law and policy. Milbank Quarterly, 88(2): 211–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2010.00596.x

Sabatino, C. (2018). POLST: Avoid the deadly sins. Bifocal, 39(4), 60-63.

Schmidt, T. A., Zive, D., Fromme, E. K., Cook, J. N., & Tolle, S. N. (2014). Physician orders for life-sustaining treatment (POLST): Lessons learned from: analysis of Oregon POLST registry. Resuscitation, 85(4): 480–485. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.11.027

Schlenk, J. S. (1997). Advance directives: Role of nurse practitioners. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 9(7), 317-321.

Sudore, R. L., Lum, H. D., You, J. J., Hanson, L. C., Meier, D. E., Pantilat, S. Z., Matlock, D. D., … Heyland, D. K. (2017). Defining advance care planning for adults: A consensus definition from: a multidisciplinary Delphi panel. Journal of Pain & Symptom Management. 53(5), 821-832. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.12.331

The Joint Commission. (2014). Comfort measures only. Retrieved from: https://manual.jointcommission.org/releases/TJC2015A/DataElem0031.html

Venneman, S. S. (2008). ‘Allow natural death' versus 'do not resuscitate': Three words that can change a life. Journal of Medical Ethics, 34(1), 2–6. doi: 10.1136/jme.2006.018317

Walston, J. D. (2019). Frailty. UpToDate. Retrieved from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/frailty

Weissman, D. E., & Meier, D. E. (2011). Identifying patients in need of a palliative care assessment in the hospital setting: A consensus report from: The Center to Advance Palliative Care. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 14(1), 1-7. doi: 10:1089/jpm.2010.0347

Xue, Q. L. (2011). The frailty syndrome: Definition and natural history. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 27(1), 1-15. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2010.08.009

Zanartu, C., & Matti-Orozco, B. (2013). Comfort measures only: Agreeing on a common definition through a survey. American Journal Hospice & Palliative Care, 30(1), 35-9. doi: 10.1177/1049909112440740