Modern nursing is complex, ever changing, and multi focused. Since the time of Florence Nightingale, however, the goal of nursing has remained unchanged - namely to provide a safe and caring environment that promotes patient health and well being. Effective use of an interpersonal tool, such as advocacy, enhances the care-giving environment. Nightingale used advocacy early and often in the development of modern nursing. By reading her many letters and publications that have survived, it is possible to identify her professional goals and techniques. Specifically, Nightingale valued egalitarian human rights and developed leadership principles and practices that provide useful advocacy techniques for nurses practicing in the 21st century. In this article we will review the accomplishments of Florence Nightingale, discuss advocacy in nursing and show how Nightingale used advocacy through promoting both egalitarian human rights and leadership activities. We will conclude by exploring how Nightingale’s advocacy is as relevant for the 21st century as it was for the 19th century.

Key words: Florence Nightingale, advocacy, nursing, profession

Nursing has never been simple. Early care stressors included exposure to the elements and a lack of knowledge as to how to treat serious injuries or diseases. Through ensuing generations, environmental conditions have improved and science has provided effective treatment pathways. However, other complexities, including societal acceptance of the profession, gender discrimination, and educational and regulatory disarray, have created a multifaceted and complicated backdrop against which nurses continue to provide the most basic of human interventions: caring.

One of the most effective tools that [Nightingale]employed was advocacy, both for individuals and for the nursing collective. In the nineteenth century, one woman, because of her religious convictions and profound vision of the potential of nursing, altered the status of nursing from that of domestic service to that of a profession (Nightingale, 1893/1949; Nightingale, 1895a). This woman, Florence Nightingale, utilized intellect, personal motivation, available opportunities, and the strength of her own persona to create a permanent professional transformation (Bostridge, 2008; Cook, 1913; Dossey, 2000). One of the most effective tools that she employed was advocacy, both for individuals and for the nursing collective. The purpose of this article is to explore Nightingale’s use of advocacy as a tool and to identify the continuing value of her conceptual and practical advocacy strategies for the nursing profession in the 21st century. In this article we will review the accomplishments of Florence Nightingale, discuss advocacy in nursing, and show how Nightingale advocated both through promoting egalitarian human rights and through her leadership activities. We will conclude by exploring how Nightingale’s advocacy is as relevant for the 21st century as it was for the 19th century.

Who Was Florence Nightingale?

On May 12, 1820, Florence Nightingale was born as the second of two daughters to English parents. As a young woman, she displayed exceptional intellect, learning multiple languages and being particularly capable in mathematics (Bostridge, 2008). Nightingale seemed to be most comfortable in the solitary activities of reading, writing in her journals, and attempting to discern purpose in her life. She deeply believed that she had a God-given purpose to better mankind, but the route to achieving this goal was unclear (Calabria & Macrae, 1994; Cook, 1913).

...her lifetime of work and her passion for improving healthcare provided nursing with a foundational philosophy for practice. As a young woman, Nightingale wished for meaningful work and began to imagine herself caring for others, defying her parents’ desire that she marry into a socially prominent family. On at least three occasions she declined proposals, indicating that she could not pursue her own goals as a married woman (Gill, 2004; Nightingale, 1859a/1978). By the age of 17 she had discerned that she had a Christian duty to serve humankind. By the age of 25 she had identified nursing as the means to fulfill this mandate (Gill, 2004). When she was 30 years old, she was permitted two brief periods of instruction in nursing at Kasiserswerth, a Protestant institution in Germany (Bostridge, 2008; Nightingale, 1851). This experience helped her to understand the essential components of basic nursing, hospital design, and personnel administration. Of even greater consequence was Nightingale’s perception that formalized education was a necessary component of nurse preparation (Nightingale, 1851).

In 1852 Nightingale was offered the superintendency of a small hospital on Harley Street in central London (Verney, 1970). During her twelve months in this position, she developed effective administrative skills, identified appropriate qualifications for those employed as nurses, and affirmed her belief that egalitarian and competent care were basic human rights for all people (Selanders, Lake, & Crane, 2010; Verney, 1970).

As Nightingale was preparing to leave the Harley Street position, she was appointed by the Victorian government to lead a group of thirty-eight women to Ottoman Turkey, to provide nursing care for British soldiers fighting the Crimean War (Bostridge, 2008; Woodham-Smith, 1983). Nightingale’s singular motivation was to improve the plight of the wounded. She stated, “...I did not think of going to give myself a position, but for the sake of common humanity” (as cited in Goldie, 1987, p.21). Her administrative skills allowed her to negotiate the male worlds of both the military and medicine. She successfully solved the issues of supply purveyance, resolved interpersonal squabbles between nursing factions, and designed care modalities in the face of massive overcrowding, incompetence, uncaring physicians, and a military structure that was outdated and inept. In a letter to her uncle, Nightingale stated that the Purveyor had intentionally withheld supplies for his own gain, noting, “This little Fitzgerald [Purveyor] has starved every hospital when his store was full- & not, as it appears from ignorance, like some of the honorable men who have been our murderers, but from malice prepense.” (Nightingale, March 6, 1856, as cited in Goldie (1987, p. 225).

On her return from the Crimea, Nightingale worked tirelessly to develop nursing as an essential and educated component of healthcare. On her return from the Crimea, Nightingale worked tirelessly to develop nursing as an essential and educated component of healthcare. Her establishment of the Nightingale School in London in 1860, and the distribution of trained nurses abroad established the basis for nursing education worldwide (Baly, 1986; Godden, 2010). Through the support of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert she was able to design improvements for the British military and establish public health standards in India (Dossey, 2000; Mowbray, 2008). Additionally, her lifetime of work and her passion for improving healthcare provided nursing with a foundational philosophy for practice (Selanders, 2005a).

Nightingale remained actively concerned with the development and behavior of the Nightingale nurses educated at the Nightingale School until her death in 1910 at age 90. Between 1872 and 1900, she wrote a series of thirteen letters to the Nightingale nurses that both documented the progress nursing made in the late nineteenth century and warned nurses that they must remain current, competent, and caring. In 1897, she wrote of the danger of relying on words over actions:

“There is no doubt that this is a critical time for nursing... ...There is a curious old legend that the nineteenth century is to be the age for women and has it not been so? Shall the twentieth century be the age for words? God forbid.” (Dossey, Selanders, Beck, & Attewell, 2005, p. 283).

Advocacy in Nursing

...advocacy has not always been a clear expectation in nursing...Early nursing education emphasized conformity and a position subservient to the physician. Advocacy has been defined as an active process of supporting a cause or position (Illustrated Oxford Dictionary, 1998). However, advocacy has not always been a clear expectation in nursing. Seminal documents in the development of the American nursing curriculum, such as Nursing and Nursing Education in the United States (Goldmark, 1923) and A Curriculum Guide for Schools of Nursing (National League of Nursing Education, 1937), do not explicitly mention advocacy. Early nursing education emphasized conformity and a position subservient to the physician. Isabel Hampton Robb, an early leader in the development of American nursing education, encouraged obedience as the primary activity of the nurse. In 1900 Robb stated:

Above all, let [the nurse] remember to do what she is told to do, and no more; the sooner she learns this lesson, the easier her work will be for her, and the less likely she will be to fall under severe criticism. Implicit, unquestioning obedience is one of the first lessons a probationer must learn, for this is a quality that will be expected from her in her professional capacity for all future time.... (Hamric, 2000, p. 103).

While Nightingale expected obedience in following the rules and medical direction, her intent was to allow nurses the autonomy of purpose to advocate for patients and the profession (Nightingale, 1893). It is probable that she would have disapproved of Robb’s emphasis on obedience.

The term ‘advocacy’ was first utilized in the nursing literature by the International Council of Nurses in 1973. The term ‘advocacy’ was first utilized in the nursing literature by the International Council of Nurses in 1973 (Vaartio & Leino-Kilpi, 2004). Today the American Nurses Association (ANA) states that high quality practice includes advocacy as an integral component of patient safety (ANA, n.d.). Advocacy is now identified both as a component of ethical nursing practice and as a philosophical principle underpinning the nursing profession and helping to assure the rights and safety of the patient. Nurses are seen as advocates both when working to achieve desired patient outcomes and when patients are unable or unwilling to advocate for themselves.

Since 1973 advocacy has been considered a major component of nursing practice - politically, socially, professionally, and academically. Despite the seeming lack of a professional focus on advocacy before the early 1970s, it is argued that Nightingale implicitly laid the foundation for nurse advocacy and established the expectation that nurses would advocate for their patients.

Nightingale and Advocacy

Nursing is now recognizing how [Nightingale's] ideas and techniques can be useful in the 21st century. The scope of Nightingale’s effect on nursing and her utilization of advocacy as a functional principle, like the profession itself, is complex. Nightingale did not directly address the concept of advocacy. She did, however, demonstrate advocacy in exceptional ways throughout her lifetime. We know of Nightingale’s actions, thoughts, and motivations through her correspondence. At least 13,000 letters remain in public archives and private collections. She was the shadow author for a number of official government documents relating to healthcare in the military and the subcontinent of India (Bostridge, 2008; Mawbray, 2008). Some of her most insightful writings, such as those found in Suggestions for Thought (Calabria & Macrae, 1994), were published privately, thus controlling the distribution to friends and colleagues. However, they are now publically available. The volumes Nightingale published for public consumption, including Notes on Hospitals (1859b/1982) and Notes on Nursing: What it is and what it is not (1860/1982), specifically outline the role of the nurse and the environment in which care should occur (Selanders, 2005b).

Nightingale was a singular force in advocating for as opposed to with individuals, groups, and the nursing profession. Her expressions of advocacy grew with age, experience, and public acceptance of her as both nurse and expert. Her significant contributions include her advocacy for egalitarian human rights and for advocacy in her leadership roles. Nursing is now recognizing how her ideas and techniques can be useful in the 21st century.

Advocacy Through Promotion of Egalitarian Human Rights

As a young woman, Nightingale became acutely aware of the unequal status and opportunity provided to men as compared to women in English society. Stark (1979) described the social structure:

Victorian England was a country in the grip of an ideology that worshipped the woman in the home. Women were viewed as wives and mothers, as potential wives and mothers, or as failed wives and mothers. The woman who was neither wife nor mother was called the “odd woman” or the “redundant woman” (p. 4).

In Nightingale’s frustration, she wrote the lengthy essay Cassandra (1859/1979), named after the tragic Greek mythological figure who, although able to predict the future, was not believed, and therefore, was powerless. As a part of this diatribe, she compares the perceived value of a woman’s activity to that of a man:

Now, why is it more ridiculous for a man than a woman to do worsted work and drive out everyday in a carriage?... Is man’s time more valuable than woman’s? or is it the difference between man and woman this, that woman has confessedly nothing to do? (Nightingale, 1859a/1979, p. 32).

Nightingale’s first significant demonstration of advocacy for individuals came as she was superintendent of the Hospital for Gentlewomen in Distressed Circumstances. On one hand, assuming the superintendency of this institution had to have been extremely daunting for a woman of 32 entering her first employment. The hospital was a newly acquired facility in poor condition with inadequate furnishings and a poorly trained staff. She reported that in the first month of occupancy she had experienced a gas leak with small explosions, a fight between workmen in the drawing room, a drunken foreman, and the death of 5 patients (Verney, 1970). On the other hand, it was the opportunity to participate in a healthcare situation under her control that allowed her to create and utilize environmental and patient care standards that were to become foundational to the development of modern nursing (Selanders, 2005a).

Nightingale did have the general support of the Ladies’ Committee, the body to whom she reported. Her first major concern, however, was a policy held by the Committee stating that only individuals who were members of the Church of England would be admitted to the institution. Nightingale could not accept this position, perhaps because of her liberal Unitarian upbringing and her deeply rooted beliefs in the value of individuals without respect to religious preference. In a private note to her close friend and ally, Mary Clarke Mohl, she airs her frustration, indicating she would leave the post if this disagreement could not be resolved:

From committees, charities, and schism, from the Church of England, from philanthropy and all deceits of the devil, good Lord deliver us. My committee refused me to take in Catholic patients; whereupon I wished them good morning, unless I might take Jews and their Rabbis to attend to them. (Verney, 1970, p. viii).

Eventually, she won the battle with the Committee so that patients of all faiths – or no faith – were equally admitted to the hospital (Verney, 1970). The importance of this event cannot be overlooked in Nightingale’s development as a social reformer and healthcare advocate. She won this encounter partially through logical persuasion, but also because of her status as a ‘lady’ – a person of the upper class. This allowed her to meet the committee members on equal social footing. Use of personal position and social acquaintances, logic and debating skills, and the development of statistical evidence were tools she would refine and employ over the next fifty years. This immediate victory helped her to retain her moral convictions and to move forward as an advocate for women and nursing (Selanders, Lake, & Crane, 2010).

Nightingale next turned her attention to the development of care standards for patients, including the right to a peaceful death. The chronically and the mentally ill were often ignored by staff. Those determined to be ‘malingerers’ and the dying did not meet the criteria for admission (Scott, 1853). Nightingale, however, accepted these patients and allowed them to remain as long as she believed that they were benefiting from care despite staff objections. For a staff member to refuse to work to Nightingale’s standard resulted in dismissal, signaling the application of administrative standards of care. This is explicitly demonstrated in her May 15, 1854, report to the Governors when she wrote, “I have changed one housemaid on account of her love of dirt and inexperience, & one nurse, on account of her love of Opium & intimidation” (Verney, 1970, p. 28).

...Nightingale never wavered from the idea that a basic human right was high-quality patient care provided by a dedicated nursing staff. Nightingale advocated for patients on a larger stage during her 20 months in Scutari and the Crimea. These nurses were individually selected for their ability to nurse, the likelihood that they would accept authority, and the expectation that they would remain for the duration of the conflict. Ultimately, many of those selected did not fulfill these criteria. However, Nightingale never wavered from the idea that a basic human right was high-quality patient care provided by a dedicated nursing staff.

Following her return to England she established similar operating principles at The Nightingale School at St. Thomas’ Hospital. Nightingale again insisted that probationer students be admitted without respect to religious preference (Bostridge, 2008). The development of educational standards in a tightly controlled environment began to elevate nursing as a respectable profession that provided women with meaningful employment (Adern, 2002).

Advocacy Through Leadership

Leadership was one of Nightingale’s innate qualities. During her fifty productive years, she continually benefited from the cumulative experiences of Harley Street, Scutari, the Crimea, and her interactions with government officials in determining the potential of nursing. Her education, social stature, extensive range of acquaintances, and international travel provided essential context, opportunity, and a public voice. Her major contributions to the profession had evolved from leadership of a few at Harley Street and in the Crimea to the professional collective. She was able to explore the potential of a refocused nursing, as opposed to remodeling the status quo.

One of Nightingale’s central themes was the importance of nursing’s role in the management of the patient environment. One of Nightingale’s central themes was the importance of nursing’s role in the management of the patient environment (Nightingale, 1859b/1982). For much of Nightingale’s life she believed in miasmatism, the idea that foul odors caused disease (Selanders, 2005c). While this was an inaccurate theory, it did focus attention on the role of the environment in relation to illness. The deplorable conditions at Scutari reinforced this viewpoint, and led to her advocating for the importance of an appropriate environment for the patient both internally and externally. She began her Notes on Nursing (1860/1982) by stating that the incidence of disease is related to “...the want of fresh air, or of light, or of warmth, or of quiet or of cleanliness...” (p. 5). All of these factors are viewed as being within the purview of nursing. Although there is dispute as to the degree that the death rate was reduced in the Crimea, it is undeniable that there was a specific link between the state of the environment and the death rate (Small, 1998). Nightingale was also a supporter of the sanitation movement in London. She joined forces with reformers, such as Farr and Chadwick, in advocating for permanent improvements in public health (Selanders, 2005c). This emphasis was later extended to her environmental work in India (Mowbray, 2008).

...she envisioned the extension of nursing as the essential force which would meet the growing healthcare needs in sectors outside of the hospital. A second major outcome/theme of Nightingale’s leadership was the establishment of the Nightingale School at St. Thomas’ Hospital in London. She advocated for educated nurses who had a knowledge base and a specific role in healthcare. Further, she envisioned the extension of nursing as the essential force which would meet the growing healthcare needs in sectors outside of the hospital. This resulted in the development of nursing in the military, midwifery, poor law nursing (care of paupers), and nurse visiting (public health nursing) (Baly, 1986). This role expansion created a full range of services in and out of the hospital and across the life span, thus further expanding the role and autonomy of the nurse.

Nightingale’s continuing complaint from adolescence and into adulthood concerned the strict social mores relative to women and work outside of the home. Nursing actually served to begin to change the location of women’s work from the home into a formal workplace. Two factors contributed to the success of this change. The first was that nursing education under the Nightingale model took place in a tightly controlled environment that included a nurses’ home with a matron who functioned as parent and guardian (Baly, 1986). This allowed families to agree to send their daughters to nursing school, as nursing education was deemed to be in safe surroundings. The second factor was that nursing was initially viewed as domestic work that had been transplanted into the hospital, thus extending the typical woman’s sphere (Selanders, 2005d).

Nightingale, Advocacy, and 21stCentury Leadership

Nightingale’s lasting legacy is a composite of her accomplishments and her vision of what can and should be undertaken by the profession. She wrote prolifically and demonstrated methods that were effective. Her lessons have become the roadmap for future generations.

Perhaps the most significant and enduring of Nightingale’s contribution to nursing is learned not by reading one document, but rather by synthesizing the entire body of literature that she wrote regarding nursing. From this body of literature can be extracted nursing’s foundational philosophical base (Selanders, 2005a). The Table summarizes the major referents defined by Nightingale as essential to nursing practice, education, and research.

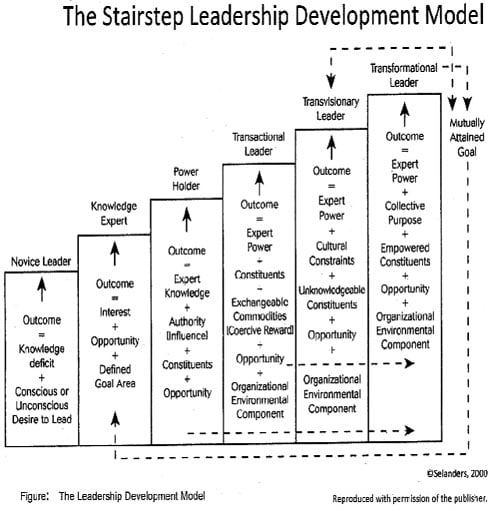

Nightingale understood the value of and the methods for achieving visionary leadership. She repetitively utilized techniques which have been developed as the stairstep leadership development model (Figure). This paradigm blends the ideas of Nightingale with the current leadership terminology of Burns (1978, 2003), who identified the relative merit of leadership outcomes, with the ‘novice-to-expert' concept of Benner (2000) which focuses on the necessity of building leadership skills.

The goal of this stairstep leadership development model is to identify a progression of stages through which individuals achieve positive leadership behaviors over time. This model does not assume that an individual holds a formal leadership position in order to demonstrate leadership; rather, it assumes that all nurses are leaders by virtue of assuming the role of nurse. The ultimate goal of this model is that leaders and followers achieve a mutually defined goal with collective purpose and long-term effectiveness (Selanders, 2005d).

...transformational leaders seek to create long-term or permanent change through the mutual identification of goals between individuals and the organization. The first three steps of the model identify the progression from novice nurse to someone who is experienced in a specific realm of nursing. This is consistent with Benner’s (2000) model. This progression may be repeated multiple times as the nurse moves from position to position. Additionally, it supports the idea that leaders are developed rather than the belief that some have innate leadership capabilities while others do not (Broome, 2011).

Expected outcomes of the model are that an individual ultimately will assume the characteristics of either a transvisionary or transformational leader. Burns (1978, 2003) has defined these levels. Transactional leaders tend to exchange valued commodities, such as exchanging work for pay. This is often coercive in nature, and while perhaps effective for the short term, does not achieve long-term results. Conversely, transformational leaders seek to create long-term or permanent change through the mutual identification of goals between individuals and the organization. This is effective in achieving change that has lasting value.

Transvisionary leadership is an appropriate goal when the leader...envision[s] a new or unusual change that may not be fully understood by constituents. Transvisionary leadership is an appropriate goal when the leader is able to envision a new or unusual change that may not be fully understood by constituents. This is effective in setting insightful goals within an organization that is experiencing new initiatives and outcomes. This is the mode that Nightingale innately chose to use out of necessity when moving nursing from a disorganized and ill-conceived occupation to a profession. A transvisionary leader relies on both expert power and opportunity to achieve results. As the leader attains effective outcomes and the goals become recognized as sound and accepted, the leadership style may move from the transactional to the transformational mode (Selanders, 2005d).

Summary

Nightingale demonstrated that advocacy is what gives power to the caring nurse. Nursing has never been simple, nor is serving as a patient advocate. However, nursing has embraced advocacy as a professional construct. Advocacy includes a complex interaction between nurses, patients, professional colleagues, and the public. Nightingale’s experiences in nursing demonstrated to her the value of advocating for nurses and patients. She embraced an egalitarian value system and utilized leadership techniques to create change in nursing. Nightingale demonstrated that advocacy is what gives power to the caring nurse.

Authors

Louise C. Selanders, RN, EdD, FAAN

E-mail: selander@msu.edu

Dr. Louise C. Selanders is a professor in the College of Nursing at Michigan State University (MSU) and Director of the MSU Nursing Master’s Program. She has extensive teaching experience in undergraduate, graduate, and lifelong education programs. Each summer, she coordinates and teaches a study abroad program in England which emphasizes the historical origins of modern, western nursing as applicable to modern practice. Dr. Selanders is internationally recognized as a Nightingale historian and scholar. She is co-author of Florence Nightingale Today: Healing, Leadership, Global Action, which received the 2005 American Journal of Nursing Book of the Year Award. She holds degrees from MSU, East Lansing, MI; Adelphi University, Garden City, NY; and Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, MI.

Patrick C. Crane, MSN, RN

E-mail: Patrick.crane@hc.msu.edu

Patrick Crane is an instructor at the Michigan State University (MSU) College of Nursing in East Lansing, MI. He currently teaches both in the MSU undergraduate nursing curriculum and in a study abroad course in London, England. This course focuses on the history of nursing, as well as the education and regulation of nurses in the United Kingdom as compared to nurses in United States. He has earned both his BSN and MSN from MSU and is currently a Doctor of Nursing Practice student at Wayne State University in Detroit, Michigan. He has addressed the role of Nightingale in the development of contemporary nursing practice through publications and presentations at national and international conferences.

© 2012 OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing

Article published January 31, 2012

References

Adern, P. (2002). When matron ruled. London: Robert Hale.

American Nurses Association. (n.d.). Advocacy. Retrieved from: www.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/ThePracticeofProfessionalNursing/PatientSafetyQuality/Advocacy.aspx

Baly, M. (1986). Florence Nightingale and the nursing legacy. Kent, England: Croom Helm.

Benner, P. (2000). From novice to expert: Excellence and power in nursing practice. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bostridge, M. (2008). Florence Nightingale: The woman and the legend. London: Penguin.

Broome, M. (2011). Leadership: Old concept, new visions. Nursing Outlook, 59, pp. 253-255.

Burns, J.M. (1978). Leadership. New York: Harper Torchbooks.

Burns, J.M. (2003). Transforming leadership: A new pursuit of happiness. New York: Grove Press.

Calabria, M & Macrae, J. (Eds.). (1994). Suggestions for thought by Florence Nightingale: Selections and commentaries. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Cook, E. (1913).The life of Florence Nightingale. (Vol 1). London: Macmillan and Co.

Dossey, B.M. (2000). Florence Nightingale: Mystic, visionary, healer. Springhouse, PA: Springhouse.

Dossey, B., Selanders, L., Beck, D., & Attewell, A. (2005). Florence Nightingale today: Healing, Leadership, Global Action Silver Spring, MD: American Nurses Association.

Gill, G. (2004). Nightingales: The extraordinary upbringing and curious life of Miss Florence Nightingale. New York: Ballantine Books.

Goldie, S. (Ed.) (1987). “I have done my duty”: Florence Nightingale in the Crimean War 1854-56. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Goldmark, J. (1923). Nursing and nursing education in the United States. New York: MacMillan.

Godden, J. (2010). The dream of nursing the empire. In S. Nelson & A.M. Rafferty (Eds). Notes on Nightingale: The influence and legacy of a nursing icon. London: ILR Press.

Hamric, A. (2000). What is happening to advocacy? Nursing Outlook, 48, 103-4.

Illustrated Oxford Dictionary. (1988). Advocacy. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Mowbray, P. (2008). Florence Nightingale and the Viceroys. London: Haus Books.

National League of Nursing League of Nursing Education. (1937). A curriculum guide for schools of nursing. New York: National League of Nursing Education.

Nightingale, F. (1851). The institution of Kaiserswerth on the Rhine. London: London Ragged Colonial Training School.

Nightingale, F. (1859a/1978). Cassandra. In R. Strachey. The cause. London: Virago, pp. 395-420.

Nightingale, F. (1859b/1982). Notes on hospitals: Being two papers read before the National Association for the promotion of Social Science at Liverpool in October, 1858. London: John W. Parker and Son.

Nightingale, F. (1860/1982). Notes on nursing: What it is and what it is not. London: Harrison.

Nightingale, F. (1893/1949). Sick nursing and health nursing. In I. Hampton (Ed.), Nursing the Sick – 1893 (pp. 24-43). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Nightingale, F. (1895a). Nursing: Training of. In R. Quain (Ed). A Dictionary of Medicine (pp. 231-2374). New York:; D. Appleton and Company.

Nightingale, F. (1895b). Nursing the sick. In R. Quain (Ed). A Dictionary of Medicine (pp. 237-244). New York:; D. Appleton and Company.

Scott, J. (1853, July 23). Benevolent institutions: Establishment for gentlewomen during illness. The Pen, 80.

Selanders, L. C. (2005a). Nightingale’s foundational philosophy for nursing. In D.B. Dossey, L.C. Selanders, D.M. Beck & A. Attewell. Florence Nightingale today: Healing, leadership, global action (pp.66-74). Silver Spring, MD: American Nurses Association.

Selanders, L. C. (2005b). Leading through theory: Nightingale’s Environmental Adaptation Theory of Nursing Practice. In D.B. Dossey, L.C. Selanders, D.M. Beck & A. Attewell. Florence Nightingale today: Healing, leadership, global action. Silver Spring, MD: American Nurses Association.

Selanders, L.C. (2005c). Florence Nightingale, dirt and germs. In D.B. Dossey, L.C. Selanders, D.M. Beck & A. Attewell. Florence Nightingale today: Healing, leadership, global action (pp. 107-113). Silver Spring, MD: American Nurses Association.

Selanders, L.C. (2005d). Social change & leadership: Dynamic forces for nursing. In D.B. Dossey, L.C. Selanders, D.M. Beck & A. Attewell. Florence Nightingale today: Healing, leadership, global action (pp. 81-89). Silver Spring, MD: American Nurses Association.

Selanders, L., Lake, K. & Crane, P. (2010). From charity to caring: Nightingale’s experience at Harley Street. Journal of Holistic Nursing. 28, 284-290.

Small, H. (1998). Florence Nightingale: Avenging angel. London: Constable and Co.

Stark, M. (1979). Cassandra: An essay by Florence Nightingale. New York: The Feminist Press.

Vaario, H. & Leino-Kilpi, H. (2004). Nursing advocacy – A review of the empirical research 1990-2003. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 42, 705-714.

Verney, H. (1970). Florence Nightingale at Harley Street: Her reports to the Governors of her nursing home 1853-4. London: W.P. Griffith & Sons Ltd.

Woodham-Smith, C. (1983). Florence Nightingale 1820-1910. New York: Atheneum.