Current service delivery designs, particularly the hospital medical-surgical “nursing unit,” may not be adequate to meet challenges facing hospitals of the future. Healthcare reform is changing the way we deliver and finance healthcare services. During this reform era there are opportunities for nurse leaders to reconceptualize the nursing role and function. This article provides a brief overview of development of modern hospitals, and describes beliefs and assumptions of an innovative design to deliver nursing services in the acute care (non-intensive care unit) setting. The proposed Service Line Model replicates the highly successful physician model that modernized U.S. hospitals. The model is driven by the Attending Nurse and the domains of nursing practice are delivered by specialists within service lines. Descriptions are provided for the nine service lines, model functioning, and next steps in development. Potential benefits of this model include greater ownership of care, reduction in clinical variation, elimination of missed care, and identification of the costs of providing nursing services.

Key Words: healthcare reform, nursing service lines, nursing domains, nursing care organization, and nursing care deliver

Healthcare reform is changing the way services are provided, the way providers are organized, and the ways healthcare is financed. The CEO of a large healthcare system recently commented that healthcare is in a once in 100 year transformation. His observation stemmed from the tremendous rate of change introduced by healthcare reform efforts over the past two decades. Healthcare reform is changing the way services are provided, the way providers are organized, and the ways healthcare is financed. These reforms have important implications for nursing. The purpose of this article is to describe an innovative model to deliver medical-surgical nursing in hospitals. The Service Line Model aligns with the tenets espoused by healthcare reform in the United States (U.S.). The article begins with a brief review of relevant healthcare reform actions, followed by an explanation of the model.

Healthcare Reform

...the U.S. healthcare industry has embarked on what will be a several decades long journey of reform to transform a hospital-based industry into an integrated healthcare delivery system. Healthcare reform has progressed in the United States in fits and starts with the release of the Flexner Report in 1910. This report is a milestone of which the serious student of healthcare reform should be aware as it was largely responsible for creating the healthcare industry we know today (Starr, 1982). Recently, a new era of reform has begun. Driven by escalating, unmanageable costs; fragmented care with poor patient outcomes; and suboptimal patient experiences the U.S. healthcare industry has embarked on what will be a several decades long journey of reform to transform a hospital-based industry into an integrated healthcare delivery system.

The beginning of this new era of healthcare reform began in 2000 with the release by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) of To Err is Human: Building: a Safer Health System (IOM, 2000), which reported that hospital errors caused 98,000 unnecessary hospital deaths each year. At the time, that would have made hospitalization the fifth leading cause of death in the United States. The companion work, Crossing the Quality Chasm (IOM, 2001), identified solutions to the quality issues present in hospitals, and the two works initiated the patient safety movement.

Performance Measurement and Public Reporting

In 1999, The Joint Commission (TJC) launched the initial set of core measures for heart failure, pneumonia, myocardial infarction, and pregnancy, requiring its client hospitals to report basic process measures related to these four conditions. A year later the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) partnered with TJC; expanded the list of core measures; and asked, then required, all hospitals to report what was becoming known as quality data. Since its inception, public reporting of quality data was criticized by hospital leaders due to issues related to the validity, importance, and fairness of the measures. However, recent evidence has indicated that quality data is becoming increasingly important in hospital annual goal setting (Goff et al., 2015; Lindenauer et al., 2014).

Public reporting of performance, an essential part of many healthcare reform strategies, has now spread to most sectors of the industry... A large part of the initial opposition by the industry to reporting quality data was the widely discussed CMS plan to share this data on the Internet. Public reporting of hospital quality data had been done previously in several states, but never in a comprehensive manner on a national scale. To that end, in 2005 the CMS launched Hospital Compare (medicare.gov) and gave consumers and competitors alike the ability to see hospitals in a way never before possible. Public reporting of performance, an essential part of many healthcare reform strategies, has now spread to most sectors of the industry covering hundreds of measures of healthcare quality, safety, outcomes, and patient experiences.

Volume to Value

One of the ACA’s most notable features was incentives to change how the industry is paid for services. The pace of healthcare reform accelerated in 2010 with the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA, 2010) and the release of the landmark IOM (2011) report, The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health. The PPACA, better known as the Affordable Care Act (ACA), provided mechanisms to make health insurance available to millions of uninsured people; outlined and incentivized new models for care delivery and payment; and increased quality data reporting (PPACA, 2010). One of the ACA’s most notable features was incentives to change how the industry is paid for services. Historically hospitals were reimbursed for the volume of services delivered, regardless of outcomes. Today, hospitals are paid for good patient outcomes (value) and not paid for services related to bad outcomes derived from the processes of care (termed Hospital Acquired Conditions). Given that nursing is the largest provider class in hospitals, the potential for nurses to improve outcomes is limitless.

The transition from volume to value is facilitated by new organizational structures created by the ACA. The foci of these new designs are to improve care coordination and quality of care while decreasing costs. The Patient Centered Medical Home is one example of these design types. Another example is the Accountable Care Organization (ACO). An ACO is a network of providers across the care continuum that agree to work together as a system of care – in essence they are regionally integrated health systems within the larger industry. Other than incentivizing providers to coordinate care, perhaps the most significant reform inherent in the ACO structure is payment risk. If the ACO network is efficient and reaches quality targets, Medicare pays a bit more; if the network falls short of national standards, the pay is less.

...providers are increasingly paid for the value their services produce, not the volume of services performed. Korda and Eldridge (2011) identified four system competencies of health reform that are embodied in ACOs. These same competencies are requisite to any system of care in the era of health reform. Firstly, care should be team-based with physicians, nurses, and other providers co-managing care. Korda and Eldridge (2011) called for flatter, less hierarchical care structures to promote collaboration and shared decision making. The second competency is improving team communication, coordination and collaboration. Medical errors and poor patient outcomes are frequently associated with ineffective communication and collaboration (Hempel, et al., 2015). The third competency is developing care delivery infrastructures that leverage team-based care and enhance safety and quality through technology (Korda & Eldridge, 2011). An integrated electronic medical record is not only a repository for patient information, but also a means of creating and communicating care planning and patient response to treatment. Korda and Eldridge’s (2011) last competency, payment to the system, and within the system, is aligned with incentives. As described earlier, providers are increasingly paid for the value their services produce, not the volume of services performed. These competencies are well known to the nursing profession and represent an opportunity for nurses to demonstrate leadership in the health reform era.

The [IOM] report identified the close link between the future of nursing and the success of healthcare reform in the United States... In The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health, the IOM (2011) identified issues and made recommendations related to the scope of nursing practice; preparing nurses for leadership roles in system transformation; development of nurse residency programs; and ensuring nurses engage in life-long learning. The report identified the close link between the future of nursing and the success of healthcare reform in the United States, and stated that current regulations, policies, organizational designs, and ways of thinking restrict nurses’ ability to bring forward innovative solutions to benefit patients. The report urged nursing leaders to reconceptualize the role of nurses across the care continuum and design new delivery systems enabling them to practice to the full extent of their education and training.

Evidence-Based Practice

Another integral component of health reform is the priority given to evidence-based practice (EBP). Another integral component of health reform is the priority given to evidence-based practice (EBP). In 2007, the IOM Roundtable on Evidence-Based Medicine reported that less than 40% of hospital care is based on research evidence supporting its efficacy. The report challenged providers to increase this number to 90% by the year 2020. The report stated that, “Care that is important is often not delivered. Care that is delivered is often not important” (IOM, 2007 p. ix).

This report (IOM, 2007) confirmed that nurses were learning evidence creation and translation skills in nursing programs at all levels, but a gap existed in the practice setting due to lack of resources to support these skills. Melnyk recently added yet another obstacle to the long list of those barriers reported to inhibit the uptake of EBP in clinical settings: resistance to EBP by nurse managers and leaders (Melnyk, Fineout-Overholt, Gallagher-Ford, & Kaplan, 2012). Citing the extensive knowledge base of the nursing profession; the capacity for independent nursing practice; and the proximity of nurses to patients, the IOM Roundtable report (IOM, 2007) speculated that the real solution to the nursing shortage may be to create work environments in which normal workflow is predicated on the principles of evidence translation.

...in some areas of service delivery much of the potential for reform has yet to be realized... These reforms, and others discussed in this OJIN topic, are creating innovative technologies, structures and processes leading to a new paradigm of healthcare service delivery. In many cases (e.g., payment reform, new methods of delivering primary care), reforms are being actively integrated into service delivery. However, in some areas of service delivery much of the potential for reform has yet to be realized, such as new organizational designs for nursing service and the translation of EBP.

This article considers the capacity for the medical-surgical “nursing unit” to meet the challenges posed by healthcare reform facing hospitals today; including a proposal for an innovative design to deliver nursing services in the acute care (non-intensive care unit) setting. The model developer believes the design would facilitate and enhance care coordination across the healthcare continuum; greatly expedite creating the evidence base for nursing practice; and reduce costs by consistently providing the “important care” (as stated by the IOM, 2007, p. ix). The Service Line Model replicates the highly successful physician model that modernized U.S. hospitals.

How Modern Hospitals Developed

Physician-Driven Model

The modern hospital we know today emerged from universities. As a result of more rigorous (and costly) state licensing standards and the release of the Flexner Report in 1910, more than half of the medical schools in the United States either merged with university hospitals or closed.

In the 1930s, Blue Cross Blue Shield launched health insurance as a popular social construct creating a much-needed, predictable funding source for the emerging hospital industry. During the Second World War factory worker wages were frozen, but collective-bargaining for health insurance benefits was allowed. By 1950, 40% of the population had benefits.

Upon finding physician resources lacking in rural and poor communities, the U.S. Congress passed the Hospital Survey and Construction Act of 1946 (Hill-Burton) with the goal of placing a hospital in every county. Hill-Burton continued to drive hospital construction throughout the United States until 1975. Medicare and Medicaid legislation passed in the mid-1960s dramatically increased hospital utilization. By 1970, there were over 7,000 hospitals in the United States (Starr, 1982).

Despite multiple iterations of healthcare reform... the basic organizational structure of the hospital was then, and is now, the nursing unit. The organizing principle of hospital industry development was the physician. Hospitals needed physicians to bring patients, resulting in competition for physician services. Patients with the same physician were placed on the same unit to increase convenience and productivity. Hospitals developed multiple ways to provide the same resources, depending on physician preference. As hospital technology and medical science advanced, hospitals supported the emergence of physician subspecialties to extend the scope of practice of the attending physician. Despite multiple iterations of healthcare reform since the Flexner Report, the basic organizational structure of the hospital was then, and is now, the nursing unit.

Nursing Unit

The nursing unit is a geographically defined, hierarchical (hence, political) organization. A management team supervises many different types of staff providing services. This basic organizational blueprint is repeated many times throughout hospitals, differing primarily by the type of patient cohort (e.g., medical, surgical, cardiac, orthopedic) traditionally assigned to the unit.

Given the volume of and similarity in these structures, there is often competition between nursing units for scarce resources or prestige. Within the nursing unit, there are nurses who have developed expertise in a clinical area and are seen as resource staff. However, for the most part, nursing staffs are considered generalists and are required to meet a broad array of diverse patient needs.

Despite the technological, professional, and social advances of the last century, the basic structure of the nursing unit has remained intact. The work of nursing units is driven by the “assignment.” Nurse assignments are made daily, often based on the nursing unit geography. Complexity and size of assignments are determined by the quantity and quality of staff present. Despite the technological, professional, and social advances of the last century, the basic structure of the nursing unit has remained intact. Within this context there have been several very different models implemented for the delivery of nursing services.

Functional Nursing focused on accountability for task completion. As hospital complexity and technology increased, Team Nursing sought to achieve efficiency by extending the scope and practice of RNs through task delegation to non-licensed personnel. Due to emerging professionalism in the profession of nursing, Primary Nursing evolved as a mechanism to integrate nursing theory and practice. Research has generated little evidence of support for efficiency and effectiveness of any particular nursing model (Tiedeman & Lookinland, 2004). The emerging model for structuring nursing services is the professional practice model. Still in its earliest stages, this model speaks to the scope, integration, and development of professional nurses (Duffy, 2016).

Modern Trends

The emerging model for structuring nursing services is the professional practice model. Healthcare reform has produced turbulent times. Reimbursement for the volume of services delivered is becoming payment for desired outcomes. Patients, who until recently were expected to be passive recipients of services, are now expected to become engaged participants. The primary focus of healthcare, previously disease mitigation (think hospital), and is changing to population health and chronic disease management (think ambulatory).

Due to healthcare reform efforts, the hospital industry is transitioning to an integrated healthcare system. Missed nursing care, or important care that should have been delivered but was not, is widespread (Kalisch, Tschannen, Lee, & Friese, 2011; Winsett, Rottet, Schmitt, Wathen, & Wilson, 2016). Particular care concerns include: ambulation, mouth care, care conference participation, timely medication delivery, patient positioning, focused reassessments, and discharge teaching/planning (Kalisch et al., 2011; Winsett et al., 2016). Medical error during hospitalization is estimated to cause more than 400,000 deaths and as many as 8 million serious harm events each year (James, 2013). Healthcare leaders have recognized the risks to patients inherent in episodic, disjointed services and are increasingly structuring care coordination processes into more aspects of service delivery. Governmental and regulatory bodies are calling for replacement of traditional practices with evidence-based, research-driven practices. Due to healthcare reform efforts, the hospital industry is transitioning to an integrated healthcare system.

It may be time to rethink the nursing unit to fully support modern trends in healthcare reform. The organizing principles of the nascent healthcare system are development of high quality processes and achievement of optimal patient outcomes. The turbulence created by these new organizing principles creates a climate favorable for nursing leaders attempting to develop mechanisms to deliver nursing services within hospitals with capacity to meet the tremendous challenges ahead. For the last 100 years, the nursing unit has remained the key building block upon which nursing services were built. It may be time to rethink the nursing unit to fully support modern trends in healthcare reform. The proposed Service Line Model (SLM) incorporates elements of the functional, team, and primary nursing models. It is the developer’s belief that a natural outcome of the Service Line Model would be the organic emergence of the professional practice model (McClelland, 2017).

Beliefs and Assumptions Inherent in the Model

The SLM is a radical redesign of hospital-based nursing services. Listed here are six underpinning beliefs which support the need for change:

- Hospital leaders do not need to fix nurses; they need to get out of their way. Nurses are inherently self-motivated, highly intelligent, and networked, life-long learners. Rather than trying to fix hospital outcomes problems by changing nurse behaviors, hospital leaders may be more successful by first providing a nursing service delivery system consistent with nurse values, and then allowing nurses to grow the system. Nurse engagement and professional development will be optimized by creating greater nursing role clarity and opportunities to consistently provide a very high level of quality care.

- Patient needs are predictable. Anecdotal evidence collected from many nurse leaders by the model developer over the past fifteen years suggests that a large percentage, perhaps as high as 65-85%, of a hospitalized patient’s care needs are predictable. In other words, hospitals know ahead of time most of what any given patient will require. If patient needs are predictable, the care can be scheduled. If care can be scheduled, it may be able to be provided by a technician.

- The “task orientation” present in the nursing profession today is a result of the nursing unit structure. The calls for critical thinking development within nurses will be answered as nurses work in systems requiring a higher level of cognitive functioning. Nurses are currently recognized for having warm hearts and strong backs. The SLM provides an opportunity to leverage nurses’ “free-floating intellect” to showcase their ability to critically think.

- Caseloads are better than assignments. The long-standing foundation of nursing has been relational care (Manthey, 1980). Assignments (often expressed as room numbers) imply no future relationship between patient and nurse. The concept of caseloads suggests, and thus fosters, a future relationship.

- Patients benefit from continuity of providers over multiple admissions.

- Hospitals should not discharge patients. The organizing principle of post-modern hospitals is care coordination. Hospitals will not discharge patients; but rather transition them to another level of care.

The Service Line Model

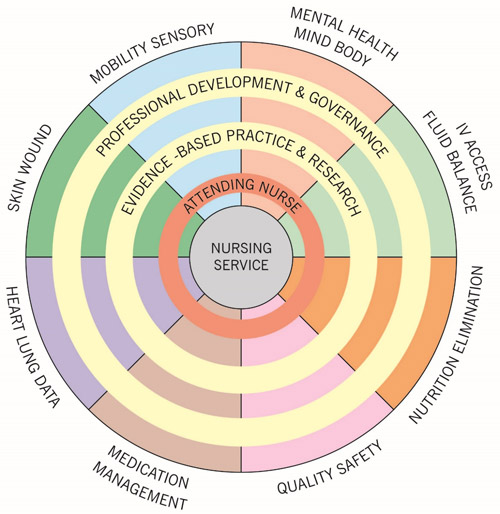

Just as medical services evolved into the subspecialties recognized today, nursing services can be organized by subspecialties (service lines). The SLM is a replication of the roles and processes used by physicians to support the rise of the hospital industry. The SLM is driven by the Attending Nurse (AN) role, quite similar in functioning and stature to the attending physician role. Just as medical services evolved into the subspecialties recognized today, nursing services can be organized by subspecialties (service lines). Given the innovative quality of the model, the cultural familiarity with the “attending” model may lend support to model credibility and potential capacity (see Figure).

Figure. The Service Line Model

Model Roles and Function

Three model roles will be described in this section: attending nurse, service lines, and supporting roles. Table 2 will then detail Service Line Model functioning and characteristics.

The AN demonstrates leadership within the inter-disciplinary team. Attending Nurse. The AN is half primary nurse and half case manager. The AN ensures that patient care needs are identified appropriately and delivered in accordance with hospital policy and national standards. These are seasoned practitioners knowledgeable about patient care needs. More often than not, the AN will complete the patient admission assessment. The AN rounds on his/her caseload of patients several times each day and collaborates with both colleagues in other service lines and members of other disciplines to establish, implement, and evaluate the plan of care. The AN demonstrates leadership within the inter-disciplinary team. As a case manager, the work of the AN focuses on care coordination and transition planning. Under the SLM, the AN (as well as the other service lines) is no longer restricted by geographic boundaries, and would be assigned to a patient on subsequent admissions.

Rather than belonging to a nursing unit and being a generalist, nurses belong to a service line and become specialists. Nursing Practice Service Lines. Rather than belonging to a nursing unit and being a generalist, nurses belong to a service line and become specialists. Nurses are not assigned to a group of patients located on one unit; they carry a caseload of patients across several geographic locations. Nurses working within a service line are accountable for assessment, planning, implementation, and evaluation of patient care needs as they relate to the domain of practice delivered by their service line. Service line nurses work closely in dyads with technicians who provide much of the routine, predictable task oriented care. For example, during rounds the Wound/Skin technician would precede the nurse to the next patient, gather supplies, and remove the old dressing. The Wound/Skin nurse assesses the old dressing and wound; performs necessary treatments; and redresses the wound. While the nurse educates the patient/family, the technician prepares the next patient. In another example, the Mobility/Sensory nurse assists a patient with ambulation to assess gait characteristics. The Mental Health/Mind-Body nurse for the same patient assists with ambulation while assessing for delirium and coping.

Table 1 identifies the domains of practice comprising the service lines. The multitude of tasks flowing from each domain are too numerous to list in the scope of this discussion, but are easily inferred. The nature of the service lines and their domains will evolve with practice. The development of competencies, by and for nurses, within the service lines will inform the evolution of the service lines.

Table 1. Domains of Nursing Practice Service Lines

|

Care Coordination/Transition Planning - Attending Nurse |

|||

|

Mobility/ Sensory

|

Mental Health/Mind-Body

|

IV Access/Fluid Balance

|

Wound/Skin

|

|

Nutrition/ Elimination

|

Medication Management

|

Quality/Safety

|

Heart/Lung/Data

|

Supporting Roles. Several additional roles support the SLM. Admission Nurses serve as backup to the AN when the AN is unavailable to perform the initial nursing assessment at time of admission. When not admitting patients, Admission Nurses help in the emergency department to facilitate identification, decision-making, and patient flow related to potential admissions. Patient Care Nursing Assistants, unaligned with a service line and geographically-based, work closely with ANs to assure that both unit based and technical and routine patient tasks are performed efficiently and effectively. A concierge role (filled by hospital volunteers) supports patient physical comforts and assists with feeding and maintaining a clean and pleasant environment. The concierge role serves as a pipeline to ongoing and future patient/family forums and councils to provide valuable input to hospital leaders.

The Service Line Model considers several areas related to functioning and characteristics. Table 2 provides information about three specific areas of consideration clinical, governance, and career advancement.

Table 2. Service Line Model Functioning and Characteristics

|

Clinical |

|

|

Governance |

|

|

Career Advancement |

|

Next Steps

Several steps are needed to continue moving forward with implementation of this innovative Service Line Model. Of particular importance is work to determine the model strengths and weaknesses; develop productivity standards; and determine clinical divisions and caseload size.

Determine Model Strengths and Weaknesses

Focus groups comprised of nurse clinicians, managers, and leaders will determine the robustness and fit of the service line domains to capture all potential patient needs. The focus groups will also explore potential strengths and weaknesses of the model.

Develop Productivity Standards

With this model, the current, widely used standard of hours per patient day become obsolete. The basic unit of nursing service delivery would be the nursing visit, or “encounter.” Initial determinations will need to include the number of patients with whom a service line nurse could effectively make rounds during 8 and 12 hour shifts. This number will drive caseload size determinations. Ultimately, these encounters will be ranked and coded according to intensity, based on skills needed, physical effort required, and amount of time consumed. Recent time and motion studies that have measured nursing activity could be informative to this process (Hendrich et al., 2008; Yen et al., 2016; Yoon et al., 2015).

Determine Clinical Divisions

In very small hospitals (approximately 20 beds), all patients would comprise one caseload which would then be the same for all service lines. In small and medium sized hospitals (approximately 20 to 250 beds), caseloads may be divided by medical and surgical divisions. Nurses wishing to work with medical patients would belong to the medical division and work within a service line providing care to that patient population. In large hospitals (250 or more beds), surgical divisions would be subdivided to include clinical subspecialties such as chest, abdominal or orthopedic surgeries. Medical divisions could be delimited in a similar fashion. All divisions will be constituted with the same service lines; the number of caseloads within the service lines would vary depending on acuity of patient needs.

Determine Caseload Size

The number of caseloads (a function of caseload size) within a service line will vary by division. For example, assuming greater mobility needs are present in the medical division (requiring a higher level of nursing time and resources), the medical division would have smaller caseloads for the Mobility/Sensory service line than would the surgical division. By contrast, the Wound/Skin service line in the surgical division may have two (smaller) caseloads and the medical division may have only one.

Potential Benefits

Reduce Clinical Variation

Rather than being a series of tasks to be completed, “care” will become the business of the service line. The reduction of clinical variation is one of the most important, as well as the most challenging, imperatives facing hospital leaders as healthcare transitions from an industry to a system (HRET, 2011). Within the SLM, nurses will “own” the care provided by their service line. Rather than being a series of tasks to be completed, “care” will become the business of the service line. Care providers will develop a commitment to the identification and integration of EBP.

Medical practice ultimately became too complex to be delivered by one type of provider, prompting the development of medical specialties. So, too, has the complexity of nursing care evolved. As nurses transition from a generalist to a specialist role, they will focus on practices critical to their service line domains. This sharper focus on specific domains of practice will enable nurses to concentrate on innovative ways to improve and standardize nursing practice. It is anticipated that nursing service would be 95% evidence-based within five years of model implementation and the remaining 5% under active research. The SLM would give nursing control over its practice and, with full implementation, may virtually eliminate missed care.

Identification of Nursing Contribution

The SLM can provide greater clarity to identify and measure nurse contribution to individual patient care. Nursing services generally do not appear on patient invoices sent to insurance companies, but included as part of the hospital room charge. The SLM can provide greater clarity to identify and measure nurse contribution to individual patient care. The billable unit of nursing services will be the encounter. Encounters will be coded in relative value units similar to reimbursements for physician services today. Ultimately, such knowledge can lead to long sought formulas to determine the true cost of providing nursing services.

Conclusion

Every system is designed perfectly to obtain the results it produces (Juran, 1988). The nursing unit was once pragmatic and effective; however, hospital and medical technological growth, and the emergence of professional nursing practice, have surpassed the nursing unit model capacity to serve as an effective organizing platform. The SLM developer believes the task orientation present in hospital nursing today flows from the hierarchical design of hospitals, particularly, the nursing unit, and not the nurses themselves.

Healthcare reform efforts across the industry are challenging traditional designs for delivering services... Healthcare reform efforts across the industry are challenging traditional designs for delivering services and calling for nursing practice reflecting the full scope of both RN and advanced practice licensure (IOM, 2011). Advancements in care coordination, practice improvement, prudent resource stewardship and patient experience does, and will continue to, require different ways of thinking and doing than in the past. The Service Line Model represents an organizational design that can consistently meet the entire range of patient care needs while creating a unified model of nursing service.

Author

Mark McClelland, DNP, RN, CPHQ

Email: mcclelm@ccf.org

Mark McClelland has 40 years of experience in healthcare in a variety of clinical and administrative settings. He joined the Cleveland Clinic Office of Nursing Research and Innovation as a Nurse Scientist in 2013 and is currently a Quality Director for Cleveland Clinic International. Prior to that, he was at George Washington University serving as an Assistant Research Professor in the Department of Health Policy, and the Project Coordinator for two emergency department quality improvement collaboratives focusing on patient flow throughout the ED and hospital. This work led him to develop the Hospital Culture of Transitions in Patient Care Survey which measures caregivers attitudes, beliefs and practices related to patient movement throughout a hospital. His most recent research focuses on nurses’ experiences making predictions about their patient outcomes. Mark’s professional interests include performance measurement, redefining primary care, creating high reliability organizations and reducing clinical practice variation. He believes the best way to ensure safety and quality is to create care cultures that value the identification, adoption, integration, and dissemination of best practices. He has published multiple peer reviewed journal articles, and written chapters in several books. Mark received his BSN from Case Western Reserve University and his masters degree in nursing administration and health policy from the University of Washington. He completed his doctorate in nursing at George Washington University.

References

Duffy, J.R. (2016). Professional practice models in nursing. New York: Springer.

Forde-Johnston, C. (2014) Intentional rounding: A review of the literature. Nursing Standard, 28(32), 37-42. doi:10.7748/ns2014.04.28.32.37.e8564

Goff, S. L., Lagu, T., Pekow, P.S., Hannon, N.S., Hinchey, C. L., Jackowitz, T.A.,... Lindenauer, P. K. (2015) A qualitative analysis of hospital leaders’ opinions about publicly reported measures of health care quality. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 41(4), 169-176.

Hempel, S., Maggard-Gibbons, M., Nguyen, D. K., Dawes, A. J., Miake-Lye, I., Beroes, J…. Shekelle, P. (2015). Wrong-site surgery, retained surgical items, and surgical fires: A systematic review of surgical never events. JAMA Surgery, 150(8), 796-805. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.0301.

Hendrich, A., Chow, M.P., Skierczynski, B.A., Lu, Z. (2008). A 36-hospital time and motion study: How do medical-surgical nurses spend their time? The Permanente Journal, 12(3), 25-34.

HRET (Health Research & Educational Trust). (2011). Health care leader action guide: Understanding and managing variation. Retrieved from http://www.hret.org/quality/projects/healthcare-leader-action-guide-understanding-managing-variation.shtml

Institute of Medicine. (2000). To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Institute of Medicine. (2001) Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Institute of Medicine. (2007). The learning healthcare system: Workshop summary (IOM roundtable on evidence-based medicine). Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Institute of Medicine. (2011). The future of nursing: Leading change, advancing health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

James, J. T. (2013). A new, evidence-based estimate of patient harms associated with hospital care. Journal of Patient Safety, 9(3), 122–128. doi:10.1097/PTS.0b013e3182948a69

Juran, J.M. (Ed.). (1988). Juran’s Quality Control Handbook (4th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Kalisch, B., Tschannen, D., Lee, H. & Friese, C. (2011). Hospital variation in missed nursing care. American Journal of Medical Quality, 26(4), 291–299. doi:10.1177/1062860610395929.

Korda, H. & Eldridge, G.N. (2011). ACOs, PCMHs, and health care reform: Nursing’s next frontier? Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice, 12(2), 100–103. doi:10.1177/1527154411416370

Lindenauer, P.K., Lagu, T., Ross, J.S., Pekow, P.S., Shatz, A., Hannon, N.,… Benjamin, E.M. (2014). Attitudes of hospital leaders toward publicly reported measures of health care quality. JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(12), 1904-1911. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5161

Manthey, M. (1980). The practice of primary nursing. Boston: Blackwell.

McClelland, M. (2017). The service line model: A novel model for delivering medical-surgical nursing services. Poster presentation at the Sigma Theta Tau International Creating Healthy Work Environments 2017 Conference, Indianapolis, IN.

Melnyk, B. M., Fineout-Overholt, E., Gallagher-Ford, L., & Kaplan, L.(2012).The state of evidence-based practice in US nurses: Critical implications for nurse leaders and educators. Journal of Nursing Administration, 42(9),410–417. doi:10.1097/NNA.0b013e3182664e0a

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) Pub. L. No. 111-148, §2702, 124 Stat. 119, 318-319. (2010). Retrieved at www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ148/pdf/PLAW-111publ148.pdf

Starr, P. (1982). The social transformation of American medicine. New York: Basic Books.

Tiedeman, M. E. & Lookinland, S. (2004). Traditional models of care delivery: What have we learned? Journal of Nursing Administration, 34(6), 291–297.

Winsett, R. P., Rottet, K., Schmitt, A., Wathen, E. & Wilson, D. (2016). Medical surgical nurses describe missed nursing care tasks--Evaluating our work environment. Applied Nursing Research, 32, 128-133. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2016.06.006

Yen P., Kelley, M., Lopetegui, M., Rosado, A. L., Migliore, E. M., Chipps, E. M. & Buck, J. (2016). Understanding and visualizing multitasking and task switching activities: A time motion study to capture nursing workflow. American Medical Informatics Association Annual Symposium Proceedings. 1264–1273

Yoon, J.Y., King, B., Pecanac, K., Brown, R., Mahoney, J. & Kuo, F. (2015). Comparison of time-and-motion observations and self-reports to capture mobility-related nursing care activities for hospitalized older adults. Research in Gerontological Nursing. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ccmain.ohionet.org/pubidlinkhandler/sng/pub/Research+in+Gerontological+Nursing/ExactMatch/39031/DocView/1704850751/abstract/6E8C8D67C4FF46B4PQ/1?accountid=50452. 8(3), 110-117. doi:10.3928/19404921-20150304-02