There are over 700 prescription and illicit opioid-related deaths each year in Washington State. Integrating the Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP) data into the electronic health record (EHR) allows providers seamless access to patient controlled substances prescription histories, thereby reducing inappropriate prescribing and overdoses. The project overview describes the study focus, investigation of barriers to integrating PDMP data into EHRs across care settings for providers in Washington State who prescribe controlled substances. An online survey tool was developed to inquire about barriers to PDMP integration. The article presents survey results, indicating that 81% of respondents were not integrating PMDP data into the EHR and 52% did not plan on integration. The discussion section considers common barriers that providers identified, such as EHR vendor inability to provide an update, difficulty accessing the PDMP, and prioritization. Cost was the most significant barrier. Discovering barriers to PDMP integration allows stakeholders to address these issues and prevent overprescribing of controlled substances.

Key Words: barriers to drug monitoring data integration, prescription drug monitoring program, safe opioid prescribing, opioid epidemic, opioids and noncancer pain, opioid abuse, opioid misuse, opioid addiction, opioid overdose deaths, health information exchange and controlled substances prescribing, prescription opioids

...there has been increasing public health concern regarding the adverse events surrounding the misuse and abuse of opioids.The opioid epidemic is one of the most critical public health problems facing America in the 21st century (Rudd et al, 2016). Debate over the use of prescription opioids for treatment of chronic non-cancer pain (CNCP) continues. Opioid prescribing is controversial because it has been demonstrated that these medications decrease pain, resulting in an improved quality of life (Martin et al, 2016; Volkow & McLellan, 2016). However, there has been increasing public health concern regarding the adverse events surrounding the misuse and abuse of opioids (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2020b; Martin et al, 2016; Rudd et al., 2016; Shah, Hayes, & Martin, 2017).

Opioid misuse is defined as using the medication for reasons other than what it was prescribed for, such as using oxycodone to relieve a headache or to help the person sleep (Volkow & McLellan, 2016; Vowles et al, 2015). Those who abuse opioids typically do not have a prescription for the medication. Those who do have a prescription and abuse opioids use them in way other than what was prescribed (NIH, 2018). This includes taking the medication via a different route than recommended, such as crushing tablets to snort or inject (NIH, 2018). Opioid abuse and misuse can occur when the medication is used to experience euphoric feelings associated with the drug, or to knowingly exceed the recommended dose (Vowles et al, 2015).

Opioid misuse is defined as using the medication for reasons other than what it was prescribed for...In 2016, more than 2 million people misused prescribed opioids for the first time, and over 40,000 deaths were related to an opioid overdose (CDC, 2020a; Department of Health and Human Services [DHHS], 2019). Forty percent of those opioid overdoses had connection with a prescription opioid. Furthermore, it is estimated that approximately 116 Americans have a fatal opioid overdose daily (CDC, 2020a; DHHS, 2019).

...it is estimated that approximately 116 Americans have a fatal opioid overdose daily.There continues to be an increase in prescribing opioids for treatment of CNCP despite adverse implications such as abuse, addiction, and overdose (CDC, 2020a, 2020b). In fact, opioids are the most prescribed and abused class of medication in the United States (Meyer et al, 2014; National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2016). In 2015, Washington State had 718 prescription and illicit opioid-related deaths (Washington State Department of Health, 2017). Thus, two major efforts are needed in the United States to reduce the opioid epidemic: 1) Assist individuals currently addicted to opioids, and 2) initiate strategies to prevent patients from becoming addicted to opioids.

More than 40 U.S. states have passed legislation creating a prescription drug monitoring program (CDC, 2020a). Prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs) are state-run electronic databases that monitor and collect data on the prescribing and dispensing of controlled prescription drugs to patients (CDC, 2020a). According to the CDC, PDMPs are among the most hopeful state-initiated interventions to refine opioid prescribing and guide clinical practice (2016). The primary goal of a PDMP is to serve as an effective public health tool in patient care by assisting providers to make better-informed treatment decisions for their patients (Deyo et al, 2018; Neven et al, 2016; Poon et al, 2016). Use of the PDMP is not mandated in Washington State, but pending regulations will change this. Currently, prescribers of opioid medications are encouraged to utilize the PDMP to identify patients at risk of drug misuse and abuse when prescribing controlled substances.

...PDMPs are among the most hopeful state-initiated interventions to refine opioid prescribing and guide clinical practice.As the opioid epidemic intensifies, integrating PDMP data with the electronic health record (EHR) through the health information exchange (HIE) would streamline health information to the provider and promote appropriate opioid prescribing (Gordon et al., 2015; Yaraghi, 2015). The health information exchange is a secure electronic medical system that merges patient records across care settings, allowing providers to access and share clinical data on demand at the time and place of patient care (Rudin et al., 2014; Yaraghi, 2015).

In July 2016, 43 governors (including Washington State), signed a compact to fight opioid addiction that included integrating use of PDMPs into EHR systems (National Governors Association [NGA], 2016). PDMP data integration shows promise of attenuating misuse and abuse of opioid prescription drugs leading to improved patient care and safety (CDC, 2020c).

Integrating PDMP data into EHR systems will bypass the need to log into separate systems...Policy makers in Washington State and throughout the United States recognize that overprescribing opioids contributes to this public health crisis (CDC, 2020c; NGA, 2016). Integrating PDMP data into EHR systems will bypass the need to log into separate systems, increase prescriber use of PDMP data, and give providers more time with their patients (Deyo et al., 2016; Poon et al., 2016). Although state legislators rally for PDMP data integration into EHR systems, less than twenty states have included access to PDMP data via the electronic health records or health information exchange (Pew Charitable Trusts, 2016).

Project Overview

Purpose and Goal

Integration increases the use of PDMPs to support clinical decision making.Integration increases the use of PDMPs to support clinical decision making. Likewise, integration would reduce interruptions that threaten an efficient workflow by eliminating a separate cumbersome sign-on process of the PDMP. Having the data readily available for providers in the EHRs would facilitate efforts to judiciously prescribe controlled substances.

The purpose of this project was to discover the complexities of integrating PDMP data into EHRs via the health information exchange in Washington State, and what might expedite better uptake of PDMP integration. It was important to open a dialogue with health system administrators and providers. We hypothesized that financial constraints comprised the most significant barrier to PDMP integration. Our goal was to identify deterrents to the process of integration to support moving forward to mitigate barriers and integrate PDMP across all group practices, hospitals, and health system settings where controlled substances are prescribed.

It was important to open a dialogue with health system administrators and providers.Confidentiality and Data Collection

This project was approved by the sponsoring university and Washington State Department of Health Institutional Review Boards. Prior to participation in the survey, respondents provided informed consent. Participants were aware they could withdraw at any time. Confidentiality was ensured by keeping responses on a password protected computer that remained in a locked file cabinet while not in use. Only the principal investigator had access to respondent replies.

Our goal was to identify deterrents to the process of integration to support moving forward to mitigate barriers...Data were collected using online surveys to examine statewide challenges to achieving integration. To better assess each participant’s insight of PDMP integration, Washington State healthcare systems currently integrating PDMP data with EHRs were compared to those who do not plan on integration. The researcher targeted providers who accessed the PDMP before prescribing controlled substances and those who did not. We asked about reasons for not using the PDMP.

Survey Methodology

The survey included five open-ended and eight closed-ended questions. Open-ended questions were related to respondent-identified barriers to integration and how the organizational stakeholders could help them overcome those barriers. Demographic information included the county the participant represented; EHR system used; and type of practice site, including a group practice, health system, or hospital setting.

We collected data from December 2017 to February 2018. Administrators and providers across various healthcare settings in eastern and western Washington that prescribe controlled substances were given access to an online survey developed to address barriers to PDMP integration. The link was sent to the Washington State Department of Health, and the Washington State Hospital and Medical Associations. Those agencies then sent the link to their affiliated members for voluntary survey participation.

The survey was initially sent to administrators exclusively. To reach a wider scope of responses, the agencies forwarded the same online survey three weeks later to their provider members. The total number of individuals who received the survey link is unknown because the survey link was forwarded by the initial agencies in a networking style distribution. The survey yielded 52 responses.

Data Analysis

One survey response had the potential to represent an entire statewide health system that encompasses several hospitals and clinics; a solo or group practice; or hospital setting. Data were analyzed using a computer-based statistical analysis program. Survey questions were first analyzed individually to keep the content organized, and then relationships were compared between the eastern and western counties in Washington.

Respondents represented a wide variety of urban and rural counties across the state of Washington.Descriptive statistics provided summaries about identified integration barriers and depicted where integration focus, education, and assistance may be most needed. Some respondents filled out the survey in its entirety while others did not, yielding surveys with incomplete data. This explains fluctuations in the sample size as depicted in the results.

Survey Results

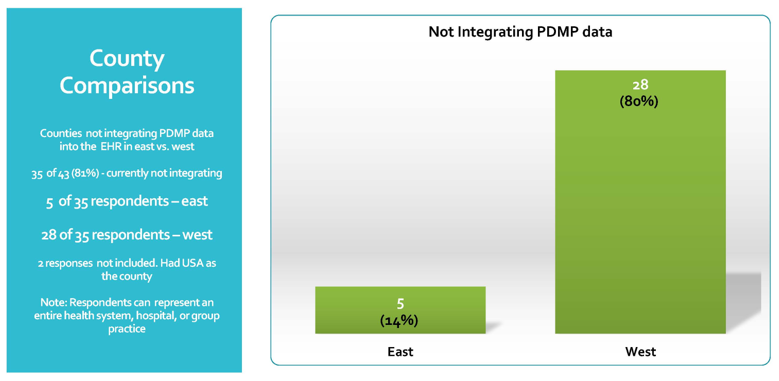

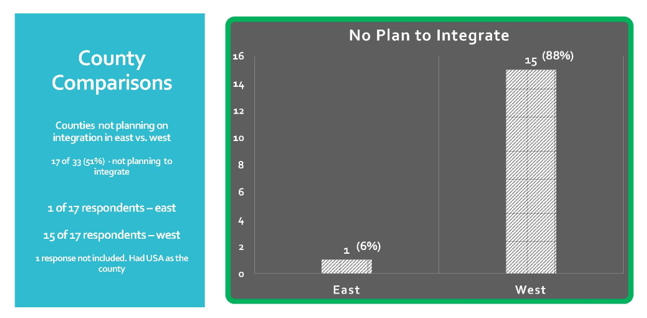

Respondents represented a wide variety of urban and rural counties across the state of Washington. However, most respondents were primarily from urban counties. Of those not integrating the PDMP, 14% were in the east and 80% in the west. Out of the 48.6% who said there was no plan to integrate, 5.9% were from the east and 88.2% were from the west. One participant was not included for this question because the county was not identified by name (see Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Eastern versus Western Counties Not Integrating PDMP (n = 35).

Figure 2. Eastern versus Western Counties with No Plan for PDMP Integration (n = 16).

Forty-five respondents identified use of 22 different EHRs with Epic™ (n = 7) and Dentrix™ (n = 7) as the main health systems (see Table 1 for representatives from each health system). Respondents represented an entire health system, group practice, or hospital. Seventy-five percent of respondents (n = 34) reported representing a group practice setting; 18% (n = 8) in a health system; and 7% (n = 3) in a hospital.

Table 1. Representation of Electronic Health Systems

|

Electronic Health System |

Number of respondents (n) |

|

Epic |

7 |

|

Dentrix |

7 |

|

Centricity |

5 |

|

Greenway |

2 |

|

Eclinical Works |

2 |

|

Office Practicum |

2 |

|

Point & Click Solutions |

2 |

|

Practice Partner |

2 |

|

Next Gen |

2 |

|

Valent |

2 |

|

Athena Net |

1 |

|

Meditech |

1 |

|

Intercom Plus |

1 |

|

All Scripts |

1 |

|

Safeway PDX |

1 |

|

PK Software |

1 |

|

PDS Proprietary |

1 |

|

Daisy |

1 |

|

DSN |

1 |

|

Various |

1 |

|

Open Dental |

1 |

|

Easy Dental |

1 |

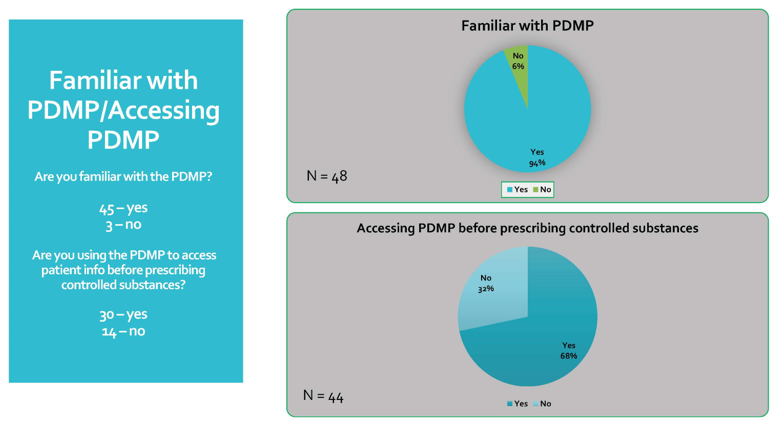

Ninety-four percent of respondents were familiar with the PDMP.Figure 3 demonstrates familiarity with PDMP. Ninety-four percent of respondents were familiar with the PDMP. For those respondents who have access to the PDMP, 68% indicated they retrieve patient PDMP data before prescribing controlled substances, and 32% responded they did not. Of those who responded they were not accessing the PDMP before prescribing, 64% (9 of 14) provided responses why they were not doing so. These reasons included time consuming and cumbersome process to access (44.4%); not signed up for the PDMP (22.2%); do not prescribe many pain meds (22.2%); and did not believe the patient population was at risk for substance abuse (11.1%).

Figure 3. Familiarity with PDMP.

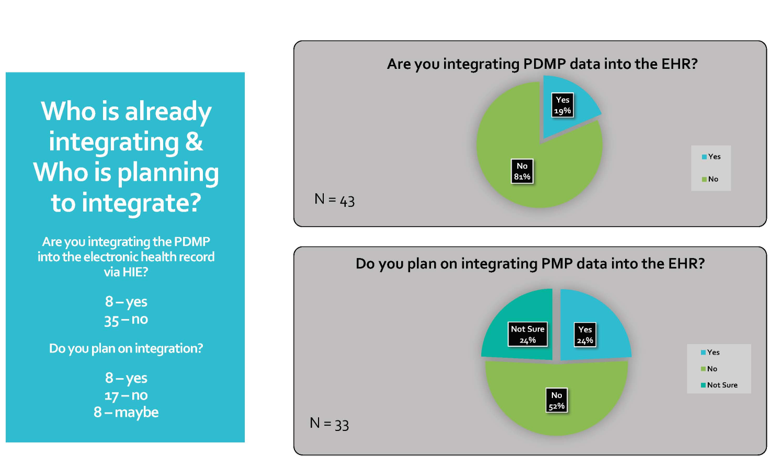

Figure 4 demonstrates who is already integrating the PDMP into the HER, and who has plans to do this. Eighty-three percent (43 of 52) of the total respondents provided information about integrating PDMP data into the EHR. Of these, 81.4% (35/43) said they were not integrating and 18.6% (8/43) reported their workplace was integrating the PDMP. Of those 33 respondents not integrating, 24% (n = 8) will soon integrate, 52% (n = 17) will not integrate the PDMP, and 24% (n = 8) said they were thinking about integration.

Figure 4. Respondents Integrating PDMP or Planning Integration.

Most respondents chose more than one barrier.Other barriers that respondents (n = 16) identified were (a) vendors unwilling or unable to provide the update to their EHR system; (b) integration was not the priority at this time; (c) current EHR system does not meet the security requirements; and (d) cost of integration (see Figure 5). Most respondents chose more than one barrier. In sum, cost, prioritization, and vendor were the main barriers identified. Reasons given about cost as a barrier included independent practice and not part of a group; limited staff; limited time to train staff; and overall cost too expensive.

Figure 5. Barriers to integration.

Finally, respondents (n = 36) provided insight about how stakeholders could help them to overcome these barriers; these suggestions are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Suggestions to Overcome Barriers

|

QUESTION: How can the Department of Health (DOH) and their partners help you overcome barriers to integration? |

|

Assist monetarily with integration |

|

Improve online training and integration process |

|

Simplify login and enrollment |

|

Provide information on integration via social media links |

|

Provide more information on how to gain access to PMP/HIE |

|

Support funding from DOH and other organizations |

|

Encourage members to enroll |

|

Collaboration among organizations |

Discussion

Our results suggested that the barriers to integration are complex.Our results suggested that the barriers to integration are complex. Cost, prioritization, and the EHR vendor being unwilling or unable to provide the update of the electronic health system were identified as the major underlying barriers. As a result, the question was raised whether many respondents understood what integration meant. Integration entails full automation, bypassing the need to log in separately to the PDMP website and eliminating the need to toggle through multiple screens.

Informing providers and administrators about what integration means in its entirety is crucial for buy-in...Staff members of the team require little if any training for successful integration. Therefore, to counter the perceived cost barrier, the Department of Health might increase efforts and communication regarding availability of resources and financial incentives to help with and encourage integration (e.g., availability of the PDMP for meeting Meaningful Use criteria). Informing providers and administrators about what integration means in its entirety is crucial for buy-in and would help to lessen the lag to adopt PMDP data integration.

Findings of this study have potential for societal benefits as states consider that PDMP integration can play an important role to address the opioid epidemic. The increased number of opioid-related deaths justifies the need for a more effective way for health systems to keep patients safe from opioid abuse and misuse. Identifying barriers to PDMP integration allows the Department of Health and their partners to consider these issues, resulting in integration of opioid prescription histories into EHR systems. Integrating PDMP data places pertinent prescription opioid information at the fingertips of the prescriber directly at the point of care. This can improve patient safety and provide another way to effectively address the opioid public health crisis.

Integrating PDMP data places pertinent prescription opioid information at the fingertips of the prescriber directly at the point of care.The major limitation of this study was the small sample size. The results may not be representative of the thousands of healthcare settings across Washington State. The small sample size reduces generalizability not only to Washington, but other states.

Conclusion

...many providers...believed that integration efforts would cause too much of a financial burden.With over 100 people dying every day from opioid-related deaths, it is difficult to place a price tag on patient safety. Integration of the PDMP into the EHR is a patient care intervention to promote safety for both the provider and the patient. However, many providers in our survey believed that integration efforts would cause too much of a financial burden for their practice. Often because providers do not see immediate results of a change, it can be hard for them to be early adopters.

For healthcare to become more progressive in nature, and improve patient outcomes, it is vital to embrace new technologies and their benefits. Meanwhile, the Department of Health and their partners must provide adequate resources to ensure that PDMP integration is achieved. Leaders in healthcare settings who rise above these barriers and move forward with integration will experience a more streamlined process to access PDMP data, likely contributing to the overall goal of decreased prescription opioid overdoses.

Authors

Sylvia May, DNP, FNP-C

Email: maysr@plu.edu

Sylvia May received a Doctor of Nursing Practice Degree (DNP) as a Family Nurse Practitioner (FNP) from Pacific Lutheran University in 2018. She will practice as an FNP in the Air Force. Her enthusiastic goal is to continue her research path addressing the opioid epidemic by translating research into practice using a collaborative approach. She is a proponent of integrated primary care and mental health services, which inspires her to obtain an additional post-master’s certificate as a psychiatric-mental health nurse practitioner. She intends to have a positive and significant impact on the nursing profession by using research to deliver high quality, equitable, and safe care to military members, their families, and civilian communities.

Chris Baumgartner, BS

Email: chris.baumgartner@doh.wa.gov

Chris Baumgartner is the Drug Systems Director at the Department of Health. Prior to his appointment in 2015, he served in various capacities for 10 years, including working for the Department as the Prescription Monitoring Program Director and owning a consulting firm that provided training and technical services to federal and state governments. He also worked for the WA State Department of Social and Health Services as an IT Portfolio Analyst and managed the Prescription Monitoring Program for the State of Maine while with the Office of Substance Abuse. Mr. Baumgartner holds a Bachelor’s of Science Degree from the University of Idaho in Computer Engineering with a Computer Science minor. In 2016 he completed a fellowship with the Informatics Training in Place Program overseen by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Gary Garrety, BA

Email: gary.garrety@doh.wa.gov

Gary Garrety is the Operations Manager for the Prescription Monitoring Program at the Washington State Department of Health. In his ten years of government service for the state of Washington he has worked to support health professionals struggling with controlled substance misuse issues to remain in good standing (licensure), and often into recovery. Mr. Garrety’s studies focused on Engineering and Mathematics while at Louisiana State University; and on Organizational Development at The Evergreen State College (2007).

Heidi McLaughlin, PhD

Email: mclaughd@plu.edu

Heidi McLaughlin is an Assistant Professor at Pacific Lutheran University. She received her PhD at the University of California, Riverside, in Developmental Psychology. She investigates how children and adults learn about and incorporate health concepts and knowledge. Her research is international in scope and includes people of all ages from the U.S., Tanzania, and Uganda. Dr. McLaughlin also teaches Statistical Analysis and has a passion for challenging students to bring to life the research they have done through statistics.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020a). Drug overdose deaths in the United States continue to increase in 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020b). Overview of an epidemic. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020c). What states need to know about PDMPs. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdmp/states.html

Department of Health and Human Services. (2019). About the U.S. opioid epidemic. https://www.hhs.gov/opioids/about-the-epidemic/

Deyo, R. A., Hallvik, S. E., Hildebran, C., Marino, M., Springer, R., Irvine, J., O’Kane, N., Van Otterloo, J., Wright, D. A., Leichtling, G., Millet, L. M., Carson, J., Wakeland, W., & McCarty, D. (2018). Association of Prescription Drug Monitoring Program use with opioid prescribing and health outcomes: A comparison of program users and nonusers. The Journal of Pain 19(2), 166-177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2017.10.001

Gordon, B. D., Bernard, K., Salzman, J., & Whitebird, R. R. (2015). Impact of health information exchange on emergency medicine in clinical decision making. The Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 16(7), 1047-1051. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2015.9.28088

Martin, C., Baerdemaeker, A. D., Poelaert, J., Madder, A., Hoogenboom, R., & Ballet, S. (2016). Controlled-release of opioids for improved pain management. Materials Today, 19(9), 491-502. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mattod.2016.01.016

Meyer, R., Patel, A. M., Rattana, S. K., Quock, T. P., & Moody, S. H. (2014). Prescription opioid abuse: A literature review of the clinical and economic burden in the United States. Population Health Management, 17(6), 372 – 387. doi: 10.1089/pop.2013.0098

National Governors Association. (2016). A compact to fight the opioid addiction.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2016). Most commonly used addictive drugs. https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/media-guide/most-commonly-used-addictive-drugs

National Institutes of Health U.S. National Library of Medicine. (2018). Opioid abuse and addiction. https://medlineplus.gov/opioidabuseandaddiction.html

Neven, D., Paulozzi, L., Howell, D., McPherson, S., Murphy, S. M., Grohs, B., Marsh, M., Lederhos, C., & Roll, J. (2016). A randomized controlled trial of a citywide emergency department care coordination program to reduce prescription opioid related emergency department visits. Journal of Emergency, 51(5), 498-507. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.06.057

Pew Charitable Trusts. (2016). Prescription drug monitoring programs: Evidence-based practices to optimize prescriber use. https://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/assets/2016/12/prescription_drug_monitoring_programs.pdf

Poon, S. J., Greenwood-Erickson, M. B., Gish, R. E., Neri, P. M., Takhar, S. S., Weiner, S. G., Schuur, J. D., & Landman, A. B. (2016). Usability of the Massachusetts prescription drug monitoring program in the emergency department: A mixed-methods study. Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, 23, 406-414. doi: 10.1111/acem.12905

Rudd, R. A., Puja, S., Felicita, D., & Scholl, L. (2016). Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths – United States, 2010 – 2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) 65(50-51), 1445-1452. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/mm655051e1.htm

Rudin, R. S., Motala, A., Goldzweig, C.L., & Shekelle, P. G. (2014). Usage and effect of health information exchange: A systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine, 16 (11), 803-811. doi: 10.7326/M14-0877

Shah, A., Hayes, J. C., & Martin, B. C. (2017). Characteristics of initials prescription episodes and likelihood of long-term opioid use – United States, 2006 – 2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), 66(10), 265-269. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/wr/mm6610a1.htm

Volkow, N. D., & McLellan, A. T. (2016). Opioid abuse in chronic pain – Misconceptions and mitigation strategies. The New England Journal of Medicine, 374, 1245-1263. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1507771

Vowles, K. E., McEntee, M. L., Julnes, P. S., Frohe, T., Ney, J. P., & Vander Goes, D. N. (2015). Rates of opioid misuse, abuse, and addiction in chronic pain: a systematic review and data synthesis. Pain Journal, 156(4), 569-576. doi: 10.1097/01.j.pain.0000460357.01998.f1

Washington State Department of Health. (2017). Opioid-related deaths in Washington State, 2006-2016 [PDF file].

Yaraghi, N. (2015). An empirical analysis of the financial benefits of health information exchange in emergency departments (2015). Journal of the American Informatics Association, 22(6), 1169-1172. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocv068