On-site, workplace clinics are one method to control today's healthcare costs. These clinics provide preventive care and treatment to employees at their place of employment, thus increasing their attendance at work. On-site clinics are particularly beneficial for decreasing the number of off-site, health-related, patient care visits. In this article, the authors describe an on-site clinic developed on a university campus. They review the history of on-site clinics, discuss the value of these clinics, present a case study describing the development of an on-site, university-campus clinic that has had a positive financial impact. They conclude that an on-site clinic can be a positive strategy to reduce healthcare costs for both the employer and the employees while promoting the health of the employees.

Key Words: employee health, advanced practice nurses, nurse practitioners, universities, health, preventive health, cost effectiveness, on-site clinics, healthcare costs, health promotion, self-insured employers, workplace wellness programs

Interest in on-site clinics has intensified in recent years. Promoting health and reducing costs related to both acute and chronic illness are concerns of organizations across the nation. One option for controlling healthcare costs is that of an on-site clinic for employees. Interest in on-site clinics has intensified in recent years (Tu, Boukus, & Cohen, 2010). On-site clinics offer healthcare services at the worksite and can provide employees access to both prevention and treatment of illnesses. Services provided by on-site clinics have moved beyond providing traditional occupational health and minor acute care services; these clinics now offer a full range of wellness and primary care services (Sherman & Fabius, 2011). Treating acute conditions at workplace clinics can eliminate trips to off-site clinics and/or emergency departments that can take hours or even the entire day. Prevention activities, such as immunizations and oversight of chronic conditions, avoid or minimize acute episodes of disease.

Employers are recognizing the need for alternatives to the existing health delivery system. Employers are recognizing the need for alternatives to the existing health delivery system. On-site clinics can provide cost-effective, quality healthcare to employees, as they provide services targeted to the needs of the workforce (Sherman & Fabius, 2011). On-site clinics add value in three ways: improved health, lowered healthcare expenditures, and improved productivity related to both reduced absences and/or to presenteeism, which occurs when employees comes to work impaired by illness and are unable to work to their full ability (Caloyeras, Liu, Exum, Broderick, & Mattke, 2014).

In this article, we will review the history and value of on-site clinics and present a case study of an on-site, university-campus clinic that has had a positive financial impact, Such a clinic is an example of how an on-site clinic can be a positive strategy to reduce healthcare costs for the employer and employees while promoting the health of employees

History of On-Site Clinics

...these clinics, usually found in large companies, existed primarily to treat occupational injuries. Workplace clinics are not a new phenomenon. In the 1980s, these clinics, usually found in large companies, existed primarily to treat occupational injuries. However, many clinics went out of business because of the decline in heavy industry and manufacturing. In the past 10 years, there has been a resurgence of on-site clinics (Tu et al., 2010). However, the current focus is now on health promotion, wellness, and primary care services. Employers, employees, and policy makers are showing an interest in workplace wellness programs; and a provision in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) encourages more employers to offer such programs. Additionally, a focus on recent increases in healthcare expenditures is a common theme in the on-site clinic literature (Bolnick, Millard, & Dugas, 2013; Caloyeras, et al., 2014; Isaac, 2013; Lerner, Rodday, Cohen, & Rogers, 2013; Marshall, Weaver, Splaine, Hefner, Kirch, & Paz, 2013; Sherman & Fabius, 2012).

Employers that provide healthcare benefits are increasingly controlling rising costs by shifting the cost burden to employees through consumer-driven, high-deductible, health plans coupled with health savings accounts (Marshall, et al., 2013). Employees can use health savings account to pay for services at the on-site clinics. In addition, employers are placing emphasis on wellness initiatives and creating incentives, such as a lower insurance premium, for participating in healthy behaviors (Marshall, et al., 2013).

Value of On-Site Clinics

On-site clinics have risen in popularity because they contribute to decreased costs, a reduction in healthcare expenditures and a positive return on the associated financial investment. These benefits are discussed below.

Decreased Cost

The cost of a visit to an on-site clinic is less expensive than the same visit to an off-site clinic. The cost of a visit to an on-site clinic is less expensive than the same visit to an off-site clinic (Tao et al., 2009). This is often due to lower operational costs at a worksite clinic than at a community clinic. Additionally, employees can seek prompt treatment for health concerns for which they would typically see a primary care provider, thereby receiving timely care and decreasing costs associated with unscheduled absences from work, the burden of which is high for companies. The cost of absences can add up in direct payroll cost and indirect costs, such as overtime to co-workers covering work of absent employees or payment for temporary workers to cover the absence, thus further increasing healthcare costs for the company (Standard Insurance Company, 2012).

Presenteeism occurs when employees come to work impaired by illnesses... Presenteeism occurs when employees come to work impaired by illnesses, such as colds; influenza; minor injuries including cuts and sprains; and chronic conditions, for example, migraines and arthritis pain (Wynne-Jones, Buck, & Proteus, 2011). Employees who are at work with these medical conditions are less likely to be fully productive than those at work who are healthy. Although presenteeism is difficult to measure, a number of studies have suggested that financial losses from presenteeism are 60 percent of the total costs of worker illnesses (Wynne-Jones et al., 2011). Having clinicians on-site can help address health conditions that affect productivity by addressing illnesses in a timely manner.

Reduction in Healthcare Expenditures

Strategies that decrease healthcare expenditures include increasing preventive care, increasing screening and early detection, establishing wellness programs, and facilitating understanding and trusting relationships among employees. Each of these strategies will be considered below.

Increasing preventive care. Preventive care, such as vaccination for influenza, will lower costs by preventing the development of a healthcare condition. Management of chronic conditions, including assessment of compliance with medication so as to prevent complications, can be provided more effectively in an on-site clinic where there is easy access to care. On-site clinics are also in the position to help the employee’s personal provider to manage chronic conditions (e.g., checking blood pressure and conducting laboratory tests for lipid or glucose management). Improvement in health outcomes related to better management of chronic conditions, such as diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia, can reduce healthcare utilization, an important measure for employers looking for cost savings (Turner, 2010).

On-site programs have been successful in working with employees to comply with evidence-based medical guidelines for diagnostic screening. Increasing diagnostic screening and early detection. On-site programs have been successful in working with employees to comply with evidence-based medical guidelines for diagnostic screening. Improved compliance is mainly attributed to a better patient–provider relationship, likely influenced by having the provider and employee working in the same place (Sherman & Fabius, 2012). Utilization of health screenings, such as mammography and colonoscopy, can provide the employer with a clear picture of the health status of employees. It should be noted, however, that health insurance companies generally provide information on employee health screenings to the employer as an aggregate report. No individual names are given, but information provided enables employers to evaluate their organizations in comparison to other employers in the state. This information can help to focus health improvement initiatives (Sherman & Fabius, 2012). On-site clinics promote health screenings through education and by providing necessary paperwork needed to have tests, such as mammography and colonoscopies.

Establishing wellness programs. Workplace wellness programs are another strategy adopted to reduce health costs through disease prevention. These programs are also a way to positively influence employee morale, retention, and productivity (Bolnick et al., 2013). In addition to increasing screening compliance, on-site programs can be administered by the on-site clinic or contracted to an outside company. On-site programs have been successful in working with employees to comply with evidence-based wellness guidelines for care. This compliance has been attributed primarily to an effective patient–provider relationship, as above and timely follow-up (Sherman & Fabius, 2012). This is an important measure for employers looking for cost savings (Turner, 2010).

Facilitating trusting relationships among employees. As noted previously, the price for unscheduled absences from work is high for companies. On-site clinicians have an understanding of the work requirements and can facilitate recovery and return to work. These clinicians facilitate communication of care needs between human resources and the employee, and assist with healthcare coverage for physical therapy or other treatments needed to get the employee back to health and back to work (Sherman & Fabius, 2012).

The value of the trusting relationship between on-site clinicians and employee should not be underestimated. The value of the trusting relationship between on-site clinicians and employee should not be underestimated. The fact that the clinician and employee are at work together helps to solidify this relationship. On-site clinicians can provide referrals to specialists in the community, coordinate employee care, and provide needed education for healthcare issues. By providing on-site care, the employer is perceived as caring for the well-being of employees, thereby improving employee satisfaction and engagement.

Positive Return-on-Investment

On-site clinics that provide medical care are implemented to reduce healthcare costs for both the organization and the employees. Employees receive prompt medical services, pay reduced co-pays, decrease the amount of time away from work, and maintain work productivity. Tao and colleagues (2009) reported that on-site clinics provide medical care at a lower cost than the cost of similar services in off-site clinics resulting in a positive return-on-investment (ROI). In a meta-analysis of the ROI from worksite health programs, Baicker, Cutler, & Song (2010) found the ROI within three years averaged $3.27 saved for every dollar spent.

A criticism of ROI studies of worksite programs is that the focus has been on newly developed programs rather than on programs that have been established for a number of years (Isaac, 2013). In response to this criticism, Henke, Goetzel, McHugh, and Isaac (2011) evaluated the effect of Johnson & Johnson’s 30-year health and wellness program. They found that Johnson & Johnson experienced a 3.7% lower average annual growth in medical costs when compared to 16 similar companies. Isaac (2013) reported that Johnson & Johnson realized a positive return-on-investment of $1.88 - $3.92 for every dollar spent. Henke and colleagues (2011) and Isaac (2013) have suggested that these cost savings are due to a strong culture of health that empowers employees to be proactive and take charge of their health.

In 2013, the RAND Corporation did a review of the PepsiCo wellness program and found that disease management, which focused on helping employees with diabetes and hypertension, had a strong ROI of $3.78 for every dollar spent on the disease management program (Mattke et al., 2014). However, it should be noted that the lifestyle management component did not reduce costs by any significant amount, as the lifestyle management program focused on identifying employees with potential healthcare risks, such as tobacco use.

On-site clinics are particularly beneficial for self-insured employers. On-site clinics are particularly beneficial for self-insured employers. Self-insured organizations offer health plans for which employers bear all or some risk for providing insurance coverage for employees and dependents. Employers who choose to self-insure maintain control over reserves, improve cash flow because coverage is not pre-paid, and reduce the cost of plan administration (McCaskill, Schwartz, Derouin, & Pegram, 2014). Stable claims due to a large employment base cover the financial risk (Park, 2000). Self-insured employers benefit from on-site health clinics because they are efficient and cost-effective. Employees who use on-site clinics have fewer outpatient and inpatient visits than their peers in the community (Prince, Spengler, & Collins, 2001).

Case Study: Development of a University Campus On-Site Clinic

This section will describe how the university identified interest in establishing a clinic, the early development of the clinic, the clinic today and the financial impact of the clinic for the university and for the employees.

Identifying Interest

As soon as our university decided to consider the development of an on-site clinic, a survey was sent out to university employees to gauge their interest in the establishment of an on-site clinic that would specifically serve employees (a student health clinic had been in place for a number of years). In 2006-2007, the university had 1,200-1,300 employees. The employees voiced their support for the availability of an on-site clinic.

Early Development

This clinic was established in June 2007 with the purpose of providing accessible, quality care to university employees. Another goal was to save money for the university in healthcare expenditures. While arrangements for the clinic were in progress, the clinic director, who is also the nurse practitioner provider of the clinic, attended faculty and staff senate meetings and department staff and faculty meetings to discuss the opening of the clinic and address questions from faculty and staff.

One important issue addressed was privacy of healthcare information. University employees were assured that the clinic would follow all regulations from the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), which provides privacy standards to protect patients’ medical records and other health information provided to health plans, doctors, hospitals, and various healthcare providers. Initially, the clinic would have paper (hard) copies of medical records. These would be kept in a locked cabinet, which in turn was in a locked room only accessible to the staff of the clinic (nurse practitioner and office assistant). Employees were reassured that no health information would be shared with supervisors, administrators, or anyone else without their explicit permission. It was reinforced that the clinic would function in the same manner as their primary provider's office in respect to handling medical records.

Space for the initial clinic was allocated in the Athletic Department. However, this necessitated that employees visiting the clinic walk through the athletes’ weight room to gain access. Bathroom facilities were located outside the clinic, in the weight room. The clinic had one usable exam room that was shared with athletic trainers. Hours of patient care services, Monday through Friday from 7:30 am to 12:00 pm, were limited by the location and sharing an exam room with the athletic trainers and team physicians.

For the first four years of operation in the Athletic Department, the clinic staff included one front office assistant and a nurse practitioner. The assistant was responsible for front office operations including reception duties, collecting patient information, making appointments, office equipment usage, ordering supplies, and record keeping. The nurse practitioner, who was both a member of the nursing faculty and director of the clinic, was responsible for all medical, nursing, and administrative functions. After four years, an additional part-time nurse practitioner was hired, and the hours of patient care were extended to 8 hours on Tuesday and Thursdays.

The Clinic Today

Today the clinic provides primary care services, management of chronic diseases, and preventive care. Today the clinic provides primary care services, management of chronic diseases, and preventive care. The most common primary care problems include respiratory ailments and dermatological issues; the most common chronic disease management issues are hypertension and lipid management; and the most common screening/preventive issues are pap smears. A list of services is given in the Table.

Table. Clinic Services

|

Prevention & Wellness |

Treatment |

Monitoring & Management |

|

Vaccinations include

|

Illness, Aches & Pains include:

|

Ongoing health conditions include:

|

|

Physicals & Wellness Visits include:

|

Minor Injuries include:

|

|

|

Health Screenings & Testing include:

|

Skin conditions include:

|

Financial Impact

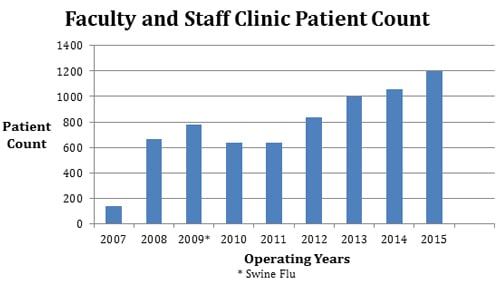

When employees used the clinic, the university saved money by not having to pay for outpatient services... From the opening of the clinic in June of 2007 to the end of September 2015, the employee count for the university ranged from 1,200 to 1,500. During this time, we have seen 1,250 faculty and staff at the clinic, for a total of 6,772 visits (see Figure). According to university insurance reports, the average amount paid for physician offsite-outpatient services per employee in 2015 was $65 (Personal Communication with UAH Human Resource Department on February 6, 2015). When employees used the clinic, the university saved money by not having to pay for outpatient services, thus meeting the goal of lowered healthcare expenditures for the organization. The savings range from $50,000 to $62,500 annually.

In addition, according to aggregate reports from the department of human resources (which receives this aggregate information from the health insurance company) sick leave usage has decreased and health insurance claims are down, keeping healthcare costs down for the employee and the university. Sick leave usage has shown a downward trend since the opening of the clinic in 2007. For example, sick leave usage for academic year 2005 to 2006 was 16,129 hours; for academic year 2006 to 2007 sick leave usage was 14,245 hours; and for academic year 2007 to 2008, sick leave usage was 11,456 hours.

Savings also included avoiding lost productivity, estimated by the number of off-site visits multiplied by the average hourly wage of employees. Lost productivity is defined as time away from work while still getting paid by the employer. The total savings over the eight years of operation from reduced claim payments and lost productivity is estimated at over $1 million. This illustrates the benefits of the on-site clinic in terms of cost-containment, while also providing quality care to employees.

Figure. Faculty and Staff Clinic: Patient Count 2007–2015

...places of work are the ideal venue to provide screening and preventive services because of the amount of time employees spend in the workplace. The clinic, initially designed as an employment benefit, today provides services to employees and retirees and saves money for the employees. Currently, the employee co-pay for an off-site provider visit is $35 while the charge for a visit to the clinic is only $5, saving the employee $30 per visit. The clinic has saved employees $203,160 ($30 x 6,772 visits) in out-of-pocket expenses. Insurance claims are not submitted because the university is self-insured. Serial monitoring of cost effectiveness is helpful to assess clinic performance; it also helps to define actual savings. It should be noted that these projected cost-savings have been calculated conservatively. It is difficult to estimate the amount of time it would take to travel round-trip to the office of the employee’s healthcare provider; the wait time to see the healthcare provider; how soon healthcare problems would be addressed; and how far in advance it would take to plan a visit to the provider’s office. In addition, the $65 per claim is for an average visit; higher level, complicated visits are charged a higher fee.

After the clinic had been operational for over eight years, functioning, growing, and serving employees and retirees, a campus-wide survey was distributed electronically in August/September 2014 via Survey Monkey© to evaluate the services of the clinic. Of 383 respondents, 70% were staff and 30% were faculty; the majority of respondents were female (65%). The quality of care received was rated as excellent (70%), and 59% of respondents indicated an interest in extending services to family members. To date, this is the only survey we have conducted, but plans are in place to survey employees annually. Responses in 2014 indicated that a majority of respondents did not like the initial location of the clinic, citing the inconvenience of walking through an athletic exercise room. Employees also demonstrated a desire for increased services and increased hours of operation. These suggestions have been used to improved services.

The clinic moved to a new location in January 2015. The new location is more central, larger, and more attractive. The clinic now has three exam rooms, and a larger, more welcoming waiting room. Hours of operation have increased to eight hours a day/forty hours per week. An electronic health record system was implemented to replace paper medical records. Privacy of electronic medical records is maintained with the use of a private server. In addition, all clinic computers are encrypted. The ‘old’ paper records are maintained in a locked cabinet in a locked room. The part-time nurse practitioner position is now a full-time position and services have expanded to include preventive care, such as well-woman visits and physical exams. We still believe that places of work are the ideal venue to provide screening and preventive services because of the amount of time employees spend in the workplace. Future plans include extending the services to family members of employees.

Conclusion

With continued increases in healthcare expenditures, use of on-site clinics can improve employee health and reduce financial burden for both employers and employees. Isaac (2013) has identified successful characteristics of the Johnson & Johnson program as comprehensiveness, high participation rate, supporting corporate leadership, and offering participants individualized programs for risk reduction. The company benefit plan also links the employee medical insurance premium to program participation. Employees that participate in the health program get a monetary reduction in premium charges (Isaac, 2013). Although currently there is no hard evidence that workers with on-site clinics are healthier than those without these clinics (Henke et. al., 2011), anecdotal evidence does describe individual employees who have benefited from on-site clinics and wellness programs. Making accurate comparisons is limited by differences in health benefits, as well as differences in the workforce and type of work (Tu et al., 2010). More research is needed to further identify these differences.

Our success with a large university clinic supports the idea that on-site clinics can be effective to reach goals of cost containment and quality healthcare services. Our success with a large university clinic supports the idea that on-site clinics can be effective to reach goals of cost containment and quality healthcare services. The on-site clinic dual focus of providing acute care and promoting health continues. Although the university does not link benefits to clinic participation, as does the Johnson & Johnson program, the employees are satisfied with the services provided, and use of the clinic continues to grow (Isaac, 2013). The administration recognizes the benefit of the clinic and has supported its expansion. This university clinic is an example of how an on-site clinic can be a positive strategy to reduce healthcare costs while promoting and enhancing the health of employees.

Authors

Louise C. O’Keefe, PhD, CRNP

Email: louise.okeefe@uah.edu

Dr. Louise C. O’Keefe serves as an Assistant Professor at The University of Alabama in Huntsville (UAH), College of Nursing, where she teaches in the Undergraduate, Graduate Family Nurse Practitioner, and Doctoral programs. Dr. O’Keefe also serves as the Director and Nurse Practitioner in the Faculty and Staff Clinic that she established on the UAH campus in 2007. Her research focuses on occupational health issues. When given the opportunity to establish an employee health clinic, she jumped at the opportunity to practice in the two areas she enjoys the most: teaching and providing care. Dr. O’Keefe believes that on-site clinics provide ready access to care and can help individuals manage their chronic health conditions successfully. Additionally on-site clinics help both to nurture a wellness culture and to retain employees who feel that the presence of an on-site clinic demonstrates an employer's willingness to invest in the health and well-being of employees.

Faye Anderson, DNS, RN, NEA-BC

Email: andersof@uah.edu

Dr. Anderson holds a Doctor of Nursing Science degree with a focus in Nursing Administration from Louisiana State University Health Science Center (New Orleans). She also holds a Master’s degree in Community Health Nursing from the University of Southern Mississippi (Hattiesburg) and a bachelor’s degree in nursing from McNeese State University (Lake Charles, LA). As a former Chief Nursing Officer, Dr. Anderson has had experience in developing plans for new or expanded projects. These activities have included identifying personnel, space, and equipment needs, as well as developing budgets, policies and marketing plans. As Associate Dean for the College of Nursing at The University of Alabama in Huntsville, she was a member of the committee exploring the possibility of opening a faculty-staff clinic. She also served as the faculty member for the Master of Leadership students who developed the cost-benefit analysis for the clinic.

References

Baicker, K., Cutler, D., & Song, Z. (2010). Workplace wellness programs can generate savings. Health Affairs, 29(2), 304-311. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0626

Bolnick, H., Millard, F., & Dugas, J. P. (2013). Medical care savings from workplace wellness programs. What is a realistic savings potential? Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 55(1), 4–9. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31827db98f

Caloyeras, J. P., Liu, H., Exum, E., Broderick, M., & Mattke, S. (2014). Managing manifest diseases, but not health risks, saved PepsiCo money over seven years. Health Affairs, 33(1), 124-131. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0625.

Henke, R., Goetzel, R., McHugh, J., & Isaac, F. (2011). Recent experience in health promotion at Johnson & Johnson: Lower health spending, strong return on investment. Health Affairs, 30(3), 490-499. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0806.

Isaac, F. (2013). A role for private industry. Comments on the Johnson & Johnson’s wellness program. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 44(1S1), S30–S33. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.09.008

Lerner, D., Rodday, A. M.., Cohen, J. T., & Rogers, W. H. (2013). A systematic review of evidence concerning the economic impact of employee-focused health promotion and wellness programs. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 55(2), 209-222. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3182728d3c

Marshall, J., Weaver, D.C., Splaine, K., Hefner, D. S., Kirch, D. G., & Paz, H. L. (2013). Employee health benefit redesign at the academic health center: a case study. Academic Medicine, 88(3), 328-334. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828a71c

Mattke, S., Hangshen, L., Caloyeras, J., Huang, C.Y., Van Busum, K.R., Khodyakov, D.,… Broderick, M. (2012). Do workplace wellness programs save employers money? RAND Corporation Research Brief Series. Retrieved from http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB9744.html

McCaskill, S. P., Schwartz, L. A., Derouin, A. L., & Pegram, A. H. (2014). Effectiveness of an on-site clinic at a self-insured university: Accost-benefit analysis. Workplace Health & Safety, 62(4), 162-169. doi: 10.3928/21650799-20140305-01

Park, C. H. (2000). Prevalence of employer self-insured health benefits: National and state variation. Medical Care Research and Review, 57(3), 340-360.

Prince, T. S., Spengler, S. E., & Collins, T. R. (2001). Corporate travel medicine: Benefit analysis of on-site services. Journal of Travel Medicine, 8(4), 163-167.

Sherman, B. W., & Fabius, R. J. (2012). Quantifying the value of worksite clinic nonoccupational health care services. A critical analysis and review of literature. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 54(4), 394-403. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31824b2157

Standard Insurance Company. (2012). Understanding presenteeism. Workplace Possibilities. Retrieved from https://www.standard.com/eforms/16541.pdf

Tao, X., Chenoweth, D., Alfriend, A. S., Baron, D. M., Kirkland, T. W., Scherb, J. L., & Bernacki, E. J. (2009). Monitoring worksite clinic performance using a cost-benefit tool. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 51(10), 1151-1157. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181b68d20

Tu, H.T., Boukus, E.R., & Cohen, G. R. (2010). Workplace clinics: A sign of growing employer interest in wellness. HSC Research Brief, 17. 1-13. Retrieved from http://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2010/12/workplace-clinics.html

Turner, D. (2010). Worksite primary care: An assessment of cost and quality metrics. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 52(6), 573-575. doi:10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181e317b6

Wynne-Jones, G., Buck, R., & Porteus, C. (2011). “What happens to work if you are unwell? Beliefs and attitudes of managers and employees with musculoskeletal pain in a public sector setting”. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 21(1), 31-42.