Lateral violence (LV), a deliberate and harmful behavior demonstrated in the workplace by one employee to another, is a significant problem in the nursing profession. The many harmful effects of LV negatively impact both the work environment and the nurse’s ability to deliver optimal patient care. In this article, the authors explain how Conti-O’Hare’s Theory of the Nurse as Wounded Healer can be used in situations of lateral violence to resolve personal and/or professional pain, build therapeutic relationships, and promote positive work environments. A working model of the theory is applied to the experience of LV in nursing to demonstrate the nurse’s path from being the ‘walking wounded’ to becoming a ‘wounded healer.’ Implications of this theory for promoting the process of healing and creating an environment that disenables violence are presented; an example is provided. The authors conclude that both practitioners and managers must be aware of the occurrence of LV and of the need for healing. They note that the ‘journey of the walking wounded’ is an ideal pathway to bring about this healing. As nurses promote health in their patients, they must also promote health in themselves and one another.

Keywords: Theory of the nurse as wounded healer, walking wounded, wounded healer, lateral violence, bullying, workplace violence, horizontal violence

Lateral violence (LV) is a devastating phenomenon in the nursing workplace. Also known as ‘horizontal violence’ or ‘workplace bullying,’ LV is disruptive and inappropriate behavior demonstrated in the workplace by one employee to another who is in either an equal or lesser position (Coursey, Rodriguez, Dieckmann, & Austin, 2013). This deliberate behavior can be openly displayed; however, it is more commonly masked and subtle as it is repeated, often escalating over time (Hutchinson, Vickers, Jackson, & Wilkes, 2006). Although individual acts may appear harmless, the cumulative effect of these personalized insults and aggressive behaviors intensify the harm more than would a single violent act (Einarsen, 2005).

Nursing has been considered the primary occupation at risk for lateral violence. Nursing has been considered the primary occupation at risk for lateral violence (Carter, 1999). Studies estimate that 44% to 85% of nurses are victims of LV; up to 93% of nurses report witnessing lateral violence in the workplace (Jacobs & Kyzer, 2010; Quine, 2001). Unfortunately, the experienced nurse is most often the perpetrator while the novice nurse is the likely victim (Jacobs & Kyzer, 2010). Randle (2003) found that nursing students and newly licensed nurses regularly witness LV and personally experience bullying in their clinical settings (Swenson, Henggeler, Schoenwald, Kaufman, & Randall, 1998). Some studies suggest that, because of its prevalence, this behavior is considered ‘normal’ and ‘accepted’ within the nursing culture; hence it is often overlooked and unreported (Hockley, 2002; Hutchinson et al., 2006; Jackson, Clare, & Mannix, 2002).

Nurses who experience LV report less trust in their organization and significantly lower job satisfaction. The harmful effects of continued exposure to LV are multiple. Victims report an overall decreased sense of well-being, physical health complaints, and depressive symptoms (Dehue, Bolman, Vollink, & Pouwelse, 2012). Their negative view of themselves, others, and the world is increased; and they frequently use ineffective coping strategies to manage their problems (Dehue et al., 2012; Mikkelsen & Einarsen, 2002). Other psychological effects can include sleep disturbances, anxiety, and even suicidal behaviors and symptoms consistent with post-traumatic stress disorder (Mikkelsen & Einarsen, 2002; Quine, 2001; Randle, 2003; Vessey, Demarco, & DiFazio, 2010). Rates of physical illness, including the onset of cardiovascular disease, are also noted to be higher in victims of LV compared to non-victimized hospital employees (Kivimaki et al., 2003). Nurses who experience LV report less trust in their organization and significantly lower job satisfaction. They are also more likely to leave, thus contributing to decreased productivity and poor communication on their units (Johnson & Rea, 2009; Quine, 2001).

Because LV is often perpetrated by nurse managers and directors, it can be difficult to report (Johnson & Rea, 2009; O'Connell, Young, Brooks, Hutchings, & Lofthouse, 2000). Yet if LV is ignored and permitted to continue, the healthcare organization can be held liable for the consequences. Additionally, there can be an increased cost to the organization, as nurses experiencing LV may leave the organization. The cost of replacing and training a medical-surgical nurse is estimated at $92,000 and the replacement cost of training a specialty nurses (e.g., a critical care or emergency department (ED) nurse) can be closer to $145,000 (Kennedy & Nichols, 2012).

The multiple effects of lateral violence ultimately both decrease a nurse’s ability to deliver optimal patient care and also compromise patient safety. In this article, we will describe how the theory of the nurse as wounded healer (NWH) facilitates nurses’ ability to address the stressors they face throughout their work life and also explain how the theory can be used in situations of lateral violence to resolve personal and/or professional pain, build therapeutic relationships, and promote positive work environments. Next, we will present implications of this theory for promoting healing and decreasing violence and offer an example of LV using the theory. In conclusion, we will encourage both practitioners and managers to be cognizant of the occurrence of LV and aware of the need for healing. As nurses promote health in their patients, they must also promote health in themselves and one another.

Theory of the Nurse as Wounded Healer

Nursing is a helping profession in which the needs of people who are in a vulnerable state are addressed by individuals who want to aid them in their recovery. Marion Conti-O’Hare (2002) believed that individuals are often led to specific professions, such as nursing, by their desire to relieve the suffering of others after experiencing or witnessing traumatic events in their own lives. This section will provide an overview of the NWH along with the origins and development of this theory.

Overview of the Theory of the Nurse as Wounded Healer

Following exposure to personal trauma, an individual’s coping strategies are either effective or ineffective. When an individual’s coping is ineffective, the impact of the trauma is unrecognized and the pain remains unresolved. These individuals then function as a ‘walking wounded,’ and experience problems in their social, intimate, and work relationships. In denying their own conflicts and vulnerabilities, these individuals project their woundedness on both patients and colleagues while considering themselves unharmed, yet being less able to empathize with others (Zerubavel & Wright, 2012).

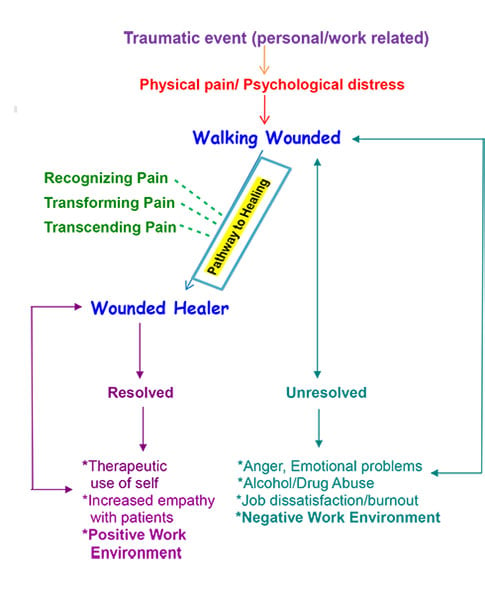

If trauma is dealt with effectively, the pain is consciously recognized, transformed, and transcended into healing. If trauma is dealt with effectively, the pain is consciously recognized, transformed, and transcended into healing (See Table 1). Although injury has occurred, the wounds will have been sufficiently understood and processed and will not interfere with providing care (Zerubavel & Wright, 2012). This processing ultimately leads to healing, despite the remaining scar. This ‘pathway to healing’ leads the nurse to become a ‘wounded healer’ and allows for the nurse to draw on his/her woundedness to provide the service of healing, as described below. Based on these premises, Conti-O’Hare developed the theory of the nurse as wounded healer to explore a nurse’s ability to transcend personal pain and suffering in order to build better therapeutic relationships with others.

|

Terms |

Operational Definitions |

|

Recognition |

Awareness that something is affecting a person in a negative manner, either through his/her own thought processes and self-evaluation, or with the assistance of other people in his/her life. |

|

Transformation |

Seeking affirmation and control over feelings of pain and/or fear through counseling and/or sharing; using energy from the past to increase understanding of the present and future. |

|

Transcendence |

A higher level of understanding (can be spiritual and/or higher thinking) that allows the person to use the understanding achieved to increase their therapeutic relationship with others. |

|

Walking Wounded |

Those who have experienced either physical or verbal trauma in their lives that they have not dealt with, allowing alterations in their ability to cope with current stressors, leading to negative results. |

|

Wounded Healer |

Those who, through self-reflection and spiritual growth, achieve expanded consciousness, through which the trauma is processed, converted, and healed. The scar remains, giving the person a greater ability to understand others’ pain. |

|

Adapted from: Conti-O'Hare, 2002, pages 145-150. |

|

Theory Origins and Development

The image of the wounded healer was first seen in Greek mythology... The image of the wounded healer was first seen in Greek mythology and has continued to be used now for over 2,500 years (Groesbeck, 1975). The archetype of the wounded healer suggests that healing power results from a healer’s own injuries, or ‘woundedness’ (Zerubavel & Wright, 2012). According to legend, after Chiron, a centaur known for his kindness, accidentally received an incurable and painful wound from Heracles’ arrow, he retreated to his cave to suffer alone. Because he was immortal, he could not die from the poison that caused his wound. Chiron moved past his own pain, and in order to heal others, he entered Hades (Groesbeck, 1975). This self-sacrificing act signified his ability to transform, transcend, and ultimately limit his suffering. He emerged as a wounded healer. Because of his past wounds, he possessed transformative qualities that are important to understanding how to assist others with the healing process.

Today the concept of the wounded healer can be found in the fields of psychiatry, psychotherapy, and religion. For a long time it has been used to describe doctor/patient relationships, with the doctor using self as an agent to assist the patient in regaining health (Groesbeck, 1975).

Carl Jung’s philosophical work expanded the concept of the wounded healer (Jung, 1953). One of Jung’s basic assumptions was that every individual has experienced some sort of trauma in life. Both conscious and unconscious factors, derived from personal experiences, drive human behavior and encompass all individuals. Instead of perceiving these factors as dichotomous, they must be recognized as co-existing. The process of identifying this ‘duality’ and seeing both parts as a whole is called ‘transcendence.’ It creates an extension of self beyond the limits of ordinary experiences. As mankind searches for transcendence, he strives to find interactions, connections, relationships, and integrations with the world around him to obtain ‘wholeness,’ in order to make sense of, define the meaning of, and find the purpose of ‘it’ all (Boeree, 2006).

Although some people have believed that healthcare providers require a problem-free psyche in order to be effective healers, Jung has suggested that professionals are just as vulnerable as the rest of mankind, and strive for wholeness rather than ‘clean-hands perfection’ when attempting to facilitate healing (Jung, 1953). He has developed his ‘counter-transference’ theory, in which he describes a wounded healer’s complete response, both conscious and unconscious, to a patient. Jung believed that the use of countertransference by a sufficiently recovered wounded healer would be beneficial to for the patient when it was used to facilitate empathetic connections and constructively inform the healing process.

More recently Fordham (1970) has maintained that the wounded healer can use past experiences to better assist others who are dealing with the same type of problem. However, if the damaged parts of the healer (healthcare provider) are not completely resolved, and the underlying pain remains, there can be negative outcomes for both the provider and the patient (Fordham).

... the nurse’s suffering is cultivated into the ability to view his or her pain as part of human growth and development. Based on Jung’s concept of the wounded healer, Marion Conti-O’Hare inductively reasoned that nursing was a profession in need of this healing process (Conti-O'Hare, 2002). She developed the theory of the nurse as wounded healer as a model of the pathway from being a ‘walking wounded’ to becoming a ‘wounded healer’ (See Figure). Her theory incorporates Jung’s assumptions into nursing, noting that nurses need to recognize their wounds, whether they be related to personal or work-related events, in order to process and transform their pain and obtain transcendence. In this context, the nurse’s suffering is cultivated into the ability to view his or her pain as part of human growth and development. The therapeutic use of self is then dependent on the degree to which the trauma is transcended; only after this transcendence can personal experience of healing be used to help others. However, if a nurse is not able to recognize personal experiences of pain and fear, emotional distress and self-destructive behaviors can result.

| Figure. Theory of the Nurse as Wounded Healer |

|

Theory developed by Marion Conti-O’Hare (2002); Figure © 2013 by Wanda Christie (co-author).

Conti-O’Hare clarified fundamental assumptions as she developed the NWH (See Table 2) (Conti-O'Hare, 2002). She explained that all human beings experience violence/trauma in their personal or their professional lives, or both. The process of healing involves moving from being a walking wounded person to being a wounded healer. The pain and fear from the experience is frequently carried throughout one’s life; it does not automatically resolve itself without an intervention. One’s ability to cope with the trauma can profoundly affect one’s ability to care for others. However, if the trauma is transformed and transcended, the experience of healing can be used to help others. The process of healing involves moving from being a walking wounded person to being a wounded healer. Becoming a wounded healer allows for the highest level of using self therapeutically. In professions in which healing is provided, the walking wounded need to first heal themselves in order to survive.

Based on these assumptions, the following four key concepts were integrated into Conti-O'Hare's theoretical framework:

- In the search for ‘wholeness,’ traumatized individuals may pass from the stage of walking wounded to wounded healer.

- Nurses and other health professionals become wounded healers after recognizing, transforming, and transcending the pain of trauma in their lives.

- Wounded healers become able to use themselves therapeutically to help others.

- This transformation will have a positive impact on the health care system, society, and the nursing profession as a whole (Conti-O'Hare, 2002).

|

All human beings experience violence/trauma in their lives. |

|

Trauma may be of a personal or professional nature, or a combination of both. |

|

Pain/fear from traumas experienced can frequently be carried throughout life. |

|

Trauma does not automatically resolve without intervention. |

|

The ability to cope with trauma has a profound effect on one’s ability to care for others. |

|

Trauma can be transformed and transcended; only then can the experience of healing be used to help others. |

|

Healing involves moving from being a ‘walking wounded’ to being a ‘wounded healer.’ |

|

Therapeutic use of self is dependent on the degree that trauma has been transformed and transcended in a person’s life. |

|

The wounded healer represents the highest level of using self therapeutically. |

|

Professions in which there are many walking wounded need to heal themselves in order to survive. |

|

* Adapted from: Conti-O'Hare, n.d. |

Theory Application to Lateral Violence in Nursing

Nursing is a high stress career, with some studies reporting the levels of stress and burnout higher among those in the nursing profession than among members of the armed forces (Calkin, 2013). Add the stressors of daily living, personal relationships, and caring for families, and there can be a tremendous amount of pressure on a nurse’s psyche. Like others, nurses are in need of an ‘outlet’ in which to vent their negative emotions and cognitions. Unfortunately, vulnerable peers and co-workers frequently end up being this outlet, thus becoming victims of lateral violence (Johnson & Rea, 2009). The most common targets include new graduates in need of mentoring, new nurses who are unfamiliar with the unit or their duties, and night shift nurses who are perceived as not working as hard as those on other shifts (White, 2006). Unfortunately, these victims then become the walking wounded, perpetuating the cycle of lateral violence (LV).

As LV is regularly witnessed or experienced on the unit... the environment can become inundated with the walking wounded. Whether the wound is caused by stressors that are work related or personal, isolated incidents of LV may begin in the form of passive aggression or mild bullying directed towards those who are perceived as lesser or weaker (Hutchinson et al., 2006). The behavior may be initially appeased with an apology; however it can also escalate to verbal abuse and other destructive behaviors, spreading negativity and creating a volatile work environment. As the attacks continue, this behavior can become the norm. As LV is regularly witnessed or experienced on the unit, and the many effects of LV consume the nursing staff, the environment can become inundated with the walking wounded. Under the premises of the theory of the nurse as wounded healer, each such nurse must first recognize and transform his or her fear and pain in order to transcend and continue along the path to become a wounded healer (Conti-O'Hare, 2002) (See Table 1). These three steps of recognition, transformation, and transcendence are delineated below.

‘Recognition’ of the trauma and its effects allows for a close examination and dissection of the components (Conti-O'Hare, 2002). The recognition process starts with the nurse asking and answering the following questions:

- What happened?

- What could be changed?

- How should it have been handled?

After recognition, the nurse can work on the next step, namely ‘transformation.’ The nurse can transform the pain into an acceptable and manageable understanding by asking:

- What can be learned from the incident?

- Has this changed me or the people I care about?

- How can this be used to make things better?

The final step, transcendence, only happens if the previous two steps have been successfully completed. Transcending the pain allows for insights and learning from past experiences that can be used to help others as they also experience pain and suffering. At this point the nurse can say:

- I understand your pain.

- How can I make things better for you?

All three steps are necessary to become a wounded healer.

...if subjected to personal trauma or LV again, nurses must repeat the process... Upon completion of this three-step process, the walking wounded becomes the wounded healer with an increased ability to understand others’ suffering and empathize with their pain (Conti-O'Hare, 2002). Professional relationships improve, resulting in a more positive work environment, and overall patient care is optimized. However, if subjected to personal trauma or LV again, nurses must repeat the process of recognition, transformation, and transcendence to regain their wounded healer status.

Implications

In 2006, the Joint Commission established standards for healthcare providers that include a standard of leadership for all. Under this leadership standard, agencies are mandated to recognize and correct behaviors that are inappropriate and disruptive within the workplace. This standard calls to action all in leadership positions (Joint Commission Resources, 2006). Early identification of inappropriate behaviors by nurse managers, and all leaders, is key to identifying and resolving lateral violence. Managers and supervisors need to be aware of individuals that demonstrate difficulty in managing stress, either in their personal lives or on the job, and help them develop appropriate stress-management strategies. Recognition of these walking wounded will ultimately assist in preventing the cycle of LV, as these individuals are not only at risk of being re-victimized, but, depending on their role on the unit, are also at risk of becoming a perpetrator.

Managers can be a catalyst to assist the nurse to initiate the first step along the pathway to becoming a wounded healer... As soon as LV begins managers should provide referrals to Employee Assistance Programs (EAP) or Human Resources (HR) Departments, asking them to provide resources for employees who need to resolve personal or professional traumas in their lives. However, such referrals should not be the end of managers’ interventions. They should also make themselves available to staff regarding any issues that may affect ability to work with others or care for patients. Managers can be a catalyst to assist the nurse to initiate the first step along the pathway to becoming a wounded healer, namely the step of recognition.

Additionally, fellow staff members should (at minimum) be aware if or when a colleague demonstrates behaviors that are disruptive, maladaptive, or dysfunctional, especially when safety of a patient is at stake. Because a colleague may not be the appropriate person to address the issue, managers should be accessible and willing to accept reports about peer concerns from staff. Peers can also provide support and mentorship for newly licensed or recently hired nurses who may experience the stress of working in a new atmosphere.

The most successful strategies feature involved administrators, staff members with positive relationships, and an obvious commitment to change. When lateral violence does become apparent in the workplace, it is imperative for administration and management to become involved. Many organizations have implemented ‘no-tolerance’ policies related to bullying and LV. While there is no consistent evidence regarding the most effective implementation of these policies, it is evident that strategies implemented need to be collaboratively prepared by administration, management, nurses, and other staff, and initiated as soon as an incident occurs (Coursey et al., 2013; White, 2006). The most successful strategies feature involved administrators, staff members with positive relationships, and an obvious commitment to change (Coursey et al., 2013) However, in an environment in which LV has become the norm, relationships may already be too strained, and motivation may be too depleted to spark the need for change.

Because the effects of LV can be significantly traumatic, managers can use the theory of the wounded healer, and the steps associated with this theory, to develop the above-mentioned strategies. Following the model, those in leadership positions should initially encourage the staff to recognize that LV is occurring, that it is traumatic, and that it has impacted the workplace negatively. This can be done both one-on-one, as well as together in a group. It is important for staff to not only evaluate the personal effects of LV, but also the effects on others and the group as a whole. Once recognition has occurred, staff can begin to explore what was learned from the experiences, again individually as well as collectively. Transforming the pain from their experiences into knowledge and understanding will assist staff to transcend it and become a wounded healer.

An Example: Mary's Story

Below is a story that has been adapted from Beth Boynton’s book, The Nurses' Guide to Improving Communication & Creating Positive Workplaces (Boynton, 2009). This example demonstrates the experiences of LV, an application of the Theory of the Nurse as Wounded Healer, and opportunities where interventions could be implemented. Listen as Mary tells her story:

Being a new nurse on any job can be hard, but being a new nurse in the Emergency Department (ED) is brutal! During my two month orientation period, I was often ignored and misinformed. My 30 years of experience didn’t matter. I was a new face in the ED and was subject to criticism and disdain as if it were my very first day as a nurse. I would say hello to staff members and they wouldn’t answer. One other ED nurse, Leah, seemed to have it in for me. One day in particular, Leah was talking and laughing with another nurse. I walked up to them, and they suddenly became silent. When I asked them what they were laughing about, Leah rolled her eyes and muttered something to the other nurse as they turned their backs to me and walked away.

Early on it is clear that LV is occurring. Mary is obviously the victim, daily being wounded as she works. Leah may be the perpetrator, but she may also be a walking wounded nurse, projecting her woundedness on others, and in need of her own healing. Other nurses seem to accept Leah’s negativity as well. Have they been exposed to the same LV and are now walking wounded, too?

One day, I didn’t want to go to lunch because I thought a patient might have an internal bleed and the doctor didn’t seem concerned. I had suggested lab work and was awaiting the results to make sure the doctor was made aware of any abnormal values. Leah encouraged to me to go to lunch and promised to watch for the results. While off the floor, I heard a code called in ED. When I got back, my patient was being rushed to the operating room. The doctor reamed me out for not reporting the critical lab values immediately. “The lab just called a minute ago,” Leah said, but I saw her half smile and shoulder shrug to the unit coordinator. I definitely wondered if she was being honest. When I said something to another staff RN, she replied: “I guess everybody has to earn their stripes.”

This situation demonstrates a definite escalation of disruptive behaviors that, unfortunately, also affected the care of a patient. Further, it appears that other staff demonstrated no support and the unit coordinator was unable to recognize the seriousness of the issue. This illustrates how LV can become the norm in a work environment, despite the risk of harm to patients.

I decided to talk to my manager about this and similar incidents. I ended up crying in her office. She told me she knew that Leah could be “hard on new people” and that “her bark was worse than her bite.” She said Leah was a crackerjack nurse with a heart of gold and for me to give it some more time. She told me that I was “showing some great potential, but should try not to be so sensitive.” I felt awful leaving her office.

Here was a key opportunity for management to intervene, not only on an individual basis, but also collectively. The nurse manager should first meet one-on-one with Mary, Leah, and the other staff and provide them with referrals to EAP or HR as needed. Individual issues can be resolved based on the wounded healer model, and this should be done first. It may be difficult for nurses who feel vulnerable in front of their peers, especially the ‘bullies,’ to address the issues. The manager should then convene a group meeting to recognize the occurrence of LV and its effects. It is necessary for all staff, including administration and managers, to collaborate and develop a ‘no-tolerance’ policy with strategies that are feasible for all. Surveys and focus groups could facilitate this process

Over the next few weeks, I dreaded going to work and started to feel very depressed and lonely. I had no mentor, and no one even offered to help me adjust. A nurse who had started two weeks after I did ended up quitting within one month. I can only wonder why? I am not happy in my job, but my family needs the income. I am not sure where I’ll be a year or two from now. Maybe here, maybe not (adapted from Boynton, 2009).

Many consequences of LV are demonstrated in Mary’s story. Due to LV, Mary has quickly lost interest in a job that she once loved and feels depressed and lonely. The ED maintained an air of negativity and quickly lost other new nurses that were hired. Management appears to be aware of the LV behaviors; in good conscience they can no longer remain blind to its effects. Staff turnover may be one loss, but patient care that is compromised is an even greater loss. In such cases, specific interventions need to occur.

Conclusion

When the safety of patients is at risk, all avenues of resolution of LV need to be taken. The Theory of the Nurse as Wounded Healer delineates how nurses can be affected by witnessing or experiencing lateral violence. The experience of LV can be as significant and painful as that of any other personal experiences of trauma; therefore, the same pathway can bring about healing. The journey of the walking wounded, through recognition, transformation, and transcendence, to become the wounded healer is an ideal pathway for the nurse to travel. Practitioners and managers must be cognizant of the occurrence of LV in order to recognize its potential effects and the need for healing. When the safety of patients is at risk, all avenues of resolution of LV need to be taken. As nurses promote health in their patients, they must also promote health in themselves and one another.

Authors

Wanda Christie, MNSc, RN

Email: wchristie@atu.edu

Ms. Christie currently teaches nursing at Arkansas Tech University in Russellville, AR. She obtained her MNSc degree in Nursing Administration from the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) in Little Rock, AR, where she is now completing her doctoral dissertation. Her research focuses on the exploration of coping mechanisms used by nurses after experiencing violence in the workplace. Ms. Christie first became interested in this topic when she read an article asking: Do nurses eat their young? Her 25 years as a staff nurse have convinced her of the need to address workplace violence with appropriate interventions.

Sara Jones, PhD, PMHNP-BC, RN

Email: SLJones@uams.edu

Dr. Jones is an Assistant Professor and Psychiatric/ Mental Health Specialty Coordinator at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) College of Nursing in Little Rock, AR. She received her BSN, PhD, and post-master’s certificate in psychiatric/mental health at UAMS. She is currently pursuing her research interests in the psychological, social, and neurobiological effects on individuals who experience trauma and on those who perpetrate violence.

© 2013 OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing

Article published December 9, 2013

References

Boeree, G. C. (2006). Carl Jung (1875-1961): Personality theories. Retrieved from www.ship.edu/%7Ecgboeree/persscontents.html

Boynton, B. (2009). The nurses' guide to improving communication & creating positive workplaces. CreateSpace, a DBA of On-Demand Publishing LLC.

Calkin, S. (2013). Nurses more stressed than combat troops. Retrived from www.nursingtimes.net/nursing-practice/clinical-zones/management/nurses-more-stressed-than-combat-troops/5053522.article

Carter, R. (1999). High risk of violence against nurses. Nursing Management - UK, 6(8), 5.

Conti-O'Hare, M. (2002). The theory of the nurse as a wounded healer: From trauma to transcendence. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

Conti-O’Hare, M. (n.d.). The theory of the nurse as wounded healer: Finding the essence of therapeutic self. Retrieved from www.drconti-online.com-theory.html

Coursey, J., Rodriguez, R., Dieckmann, L., & Austin, P. (2013). Successful implementation of policies addressing lateral violence. AORN Journal, 97(1), 101-109.

Dehue, F., Bolman, C., Vollink, T., & Pouwelse, M. (2012). Coping with bullying at work and health related problems. International Journal of Stress Management, 19(3), 175-197. doi:10.1037/a0028969

Einarsen, S. (2005). The nature, causes and consequences of bullying at work: The Norwegian experience. Pistes: Perspectives Interdisciplinaires sur le Travail et la Santi, 7(3).

Fordham, M. (1970). Reflections on training analysis. The Journal of Analytical Psychology, 15(1), 59-71.

Groesbeck, C. J. (1975). The archetypal image of the wounded healer. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 20(2), 122.

Hockley, C. (2002). Silent hell: Workplace violence and bullying. Norwood: Peacock Publications.

Hutchinson, M., Vickers, M., Jackson, D., & Wilkes, L. (2006). Workplace bullying in nursing: Towards a more critical organisational perspective. Nursing Inquiry, 13(2), 118-126.

Jackson, D., Clare, J., & Mannix, J. (2002). Who would want to be a nurse? Violence in the workplace--A factor in recruitment and retention. Journal of Nursing Management, 10(1), 13-20.

Jacobs, D., & Kyzer, S. (2010). Upstate AHEC lateral violence among nurses project. South Carolina Nurse, 17(1), 1.

Johnson, S. L., & Rea, R. E. (2009). Workplace bullying: Concerns for nurse leaders. Journal of Nursing Administration, 39(2), 84-90.

Joint Commission Resources. (2006). Civility in the health care workplace: Strategies for eliminating disruptive behavior. Joint Commission Perspecitve of Patient Safety, 6(1), 1-8.

Jung, C. G. (1953). The practice of psychotherapy: The collected works o f C. G. Jung. In H. Read, M. Fordham & G. Adler (Eds.), Bollingen Series XX (Volume 16). New York: Pantheon Book.

Kennedy, J., Nichols, A.A., Halamek, L.P., & Arafeh, J.M. (2012). Nursing department orientation: Are we missing the mark? Journal for Nurses in Staff Development, 28(1), 24-26. doi: 10.1097/NND.0b013e318240a6f3

Kivimaki, M., Virtanen, M., Vartia, M., Elovainio, M., Vahtera, J., & Keltikangas-Joñrvinen, L. (2003). Workplace bullying and the risk of cardiovascular disease and depression. Occupational & Environmental Medicine, 60(10), 779-783.

Mikkelsen, E. G., & Einarsen, S. (2002). Basic assumptions and symptoms of post-traumatic stress among victims of bullying at work. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 11(1), 87-111.

O'Connell, B., Young, J., Brooks, J., Hutchings, J., & Lofthouse, J. (2000). Nurses' perceptions of the nature and frequency of aggression in general ward settings and high dependency areas. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 9(4), 602-610.

Quine, L. (2001). Workplace bullying in nurses. Journal of Health Psychology, 6(1), 73-84.

Randle, J. (2003). Bullying in the nursing profession. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 43(4), 395-401.

Swenson, C. C., Henggeler, S. W., Schoenwald, S. K., Kaufman, K. L., & Randall, J. (1998). Changing the social ecologies of adolescent sexual offenders: Implications of the success of multisystemic therapy in treating serious antisocial behavior in adolescents. Child Maltreatment, 3(4), 330-338.

Vessey, J., Demarco, R., & DiFazio, R. (2010). Bullying, harassment, and horizontal violence in the nursing workforce: The state of the science. Annual Review of Nursing Research, 28, 133-157. doi: 10.1891/0739-6686.28.133

White, D. (2006). The hidden costs of caring: wWhat managers need to know. Health Care Manager, 25(4), 341-347.

Zerubavel, N., & Wright, M. (2012). The dilemma of the wounded healer. Psychotherapy, 49(4), 482-491. doi: 10.1037/a002782