Policy frames nursing practice in the most fundamental way: through state nurse practice acts (NPA) which date back over one hundred years in many states. NPAs frame nursing practice by defining a professional scope and educational requirements for practice. NPAs have not remained stagnant over the past century, rather they have evolved – but only with the active involvement of nurses in legislative efforts to change statute and update policies related to nursing practice. However, changing practice through policy does not stop with the NPA. This article will begin by briefly addressing the role of nurses in advocacy to advance professional practice, and offer background information about the changing healthcare industry that has influenced the example of advocacy we discuss. We offer exemplars that illustrate policies that regulate the environment of practice, such as nurse staffing, musculoskeletal injury prevention, and failure to advocate, and discuss needed protections, including whistleblower protections in our state. We conclude by considering implications for nursing organizations and nurses among these exemplars.

Key Words: nurse, nurse advocacy, health policy, legislation, nurse practice act, whistleblower

Nurses have been advocating for change since the day Florence Nightingale penned an urgent missive to the Secretary of State for War on the need for trained nurses to care for the wounded soldiers in the Crimea. Nightingale’s post-war work on hospital reform is among her most lasting accomplishments (Small, 2017). She collected, analyzed, and presented evidence to decision-makers on improved nutrition and hydration, sanitation, and ventilation for hospitalized patients (Kudzma, 2006). Establishing a foundation for the role of nurses in evidence-based advocacy, she emphasized the progressive nature of nursing, urging:

“Let whoever is in charge keep this simple question in her head (not, how can I always do this right thing myself, but) how can I provide for this right thing to be always done?” (Nightingale, 1860, p. 40-41).

As we begin 2020, designated by the World Health Organization ([WHO], 2019) as the “Year of the Nurse and Midwife,” policy change remains among the most effective approaches to create the circumstances for the right thing to be done. Since the beginning of the profession, through individual and collective efforts, nurses have changed practice through policy by addressing systemic barriers to optimal patient care and healthy environments through establishment of standards, regulations, and policy.

Since the beginning of the profession, through individual and collective efforts, nurses have changed practice through policy...Although Ms. Nightingale was often successful in single-handedly influencing policy through her relationships with military and hospital leaders, most policy work involves collaboration among nurses and other stakeholders. The American Nurses Association ([ANA], n.d., para. 1) describes the organization’s history starting in 1896 as “the story of individual nurses everywhere” united in common cause to advance nursing practice. This article will begin by briefly addressing the role of nurses in advocacy to advance professional practice, and offer background information about the changing healthcare industry that has influenced the example of advocacy we discuss. We then offer exemplars that illustrate policies that regulate the environment of practice, such as nurse staffing, musculoskeletal injury prevention, and failure to advocate, and discuss needed protections, including whistleblower protections. We conclude by considering the common thread among these exemplars.

...most policy work involves collaboration among nurses and other stakeholders.Nursing practice is regulated at the state level, therefore most of the exemplars in this article are from Texas, our state. We offer these to affirm the work of these nurses and organizations as we celebrate nurses this year. However, we recognize that there are stories from every state that highlight the valuable work of many nurses that illustrate individual and collective nursing organization advocacy.

Advocacy to Advance Practice

Advocacy in Nursing Regulation: Nurse Practice Acts

The original intent of nurse practice acts was the regulation of nursing practice through registration, now licensure (Russell, 2012). North Carolina enacted the first nurse registration law in 1903. Licensure eligibility criteria and the first licensure exam were developed in 1904. (North Carolina Board of Nursing, 2019). A few years later, nineteen nurses convened on February 22, 1907 to establish the Graduate Nurses’ Association of Texas, later renamed the Texas Nurses Association (TNA). One of the first objectives of the new organization was the passage of legislation in 1909 requiring registration of nurses through a Board of Nurse Examiners, creating the first nurse practice act in Texas (Brown, 2010).

Nursing education programs first evolved outside of the general education system through hospital-based “education for service” models. Setting standards for nursing education was an important component of early nursing regulation (Russell, 2012).

Nurses have an ethical imperative to engage in policy.Advocacy as an Ethical Duty

Nurses have an ethical imperative to engage in policy. The ANA (2015) adopted its first formal code of ethics in 1950 to express the values and ideals for the nursing profession. Over the years, the core values of nursing have remained constant and principles upheld, while specific concerns have evolved and been clarified. Nurse participation in health policy was recognized with the inclusion of the nurse-as-advocate role, added in 1976. Revision of the code in 1995 expanded it to include social ethics, global concerns, and emphasis on the important role of nurses in health policy. The most recent iteration of the code (ANA, 2015) addresses the ethical imperative for engagement in policy. Despite this emphasis, nurses do not often consider how policy affects the professional nursing role (Taft & Nanna, 2008)

Changing Healthcare Industry

Several changes in the healthcare industry have influenced the advocacy efforts of individual nurses and nursing organizations. A brief overview is offered here to provide perspective related to the specific exemplars we discuss.

Several changes in the healthcare industry have influenced the advocacy efforts of individual nurses and nursing organizations.Hospitals were compelled to focus specifically on safety when in 1999 the Institute of Medicine (IOM) released its groundbreaking report, To Err is Human (Kohn, Corrigan, & Donaldson, 2000). This report revealed disturbing insights into the prevalence of medical errors in healthcare and the consequences of those errors. With the increasing availability of information about preventable errors and complications of hospital care, particularly those related to nursing care, hospitals were called to higher levels of accountability for patient outcomes. This accountability came in the form of changes in payment policy.

In the fall of 2007, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced that it would no longer reimburse hospitals for nursing-related, preventable complications occurring during a patient hospital stay (The George Washington University, 2007). Non-reimbursable conditions include hospital-acquired pressure ulcers and readmissions. Health insurance companies have followed suit with pay-for-performance and shared-savings programs (Wallace, Cropp, & Coles, 2016).

Initially, outcomes data related to nurse staffing was sparse.Measurements of quality shifted away from an interest in structure and process, and instead targeted outcomes: patient, staff, and financial. Discussions of nurse staffing followed these trends. Where creative models of care to reduce costs dominated dialogue around nurse staffing in the 1990s, attention was cued to staffing outcomes following the IOM report. Initially, outcomes data related to nurse staffing was sparse. In the mid- to late-1990s, the American Nurses Association (ANA) led nursing efforts to identify measures that would link availability of nursing services to quality (ANA, 1997; Montalvo, 2007).

These efforts culminated in the development of the National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators™ (NDNQI®). The NDNQI® provided one of the first databases of patient and nurse outcome indicators and it is currently the only national database containing unit level data regarding nurse sensitive indicators. This database includes measures directly related to nursing care and patient outcomes (Montalvo, 2007) such as: nursing hours per patient days; hospital-acquired infections and pressure ulcers; and skill mix (percent of total nursing hours supplied by different types of direct care providers).

For the first time, patient outcomes could be specifically mapped to nursing care...Because the NDNQI® provided unit level data, it enabled comparisons across like units and like hospitals. For example, a telemetry unit in one small community hospital can compare its pressure ulcer and vacancy rates to a similar unit in another community hospital. For the first time, patient outcomes could be specifically mapped to nursing care, not just by morbidity or medical complications, but by outcomes that are specifically amenable to nursing management and intervention. This database became a powerhouse of information for researchers interested in studying relationships between nursing staff characteristics and patient outcomes (Dunton, 2007).

Exemplars of Advocacy

Nurse Staffing

Staffing involves a process of matching and providing staff resources to patient care needs. Nurse staffing is resource intensive and is the largest component of hospital operational budgets. Decades of research have confirmed the relationship between nurse staffing and patient outcomes such as mortality (Aiken et al., 2012; Aiken, Clarke, Sloane, Lake, & Cheney, 2008), healthcare-associated infections (Cimiotti, Aiken, Sloane, & Wu, 2012), financial, and nurse outcomes (Unruh, 2008).

Nurse staffing is resource intensive and is the largest component of hospital operational budgets.The complexity of nursing characteristics (e.g., skill mix); patient characteristics (e.g., acuity and case mix); and the interaction of these variables within the hospital environment make it extremely difficult to define a template as simple as a nurse-to-patient ratio to ensure appropriate staffing (Kane, Shamliyan, Mueller, Duval, & Wilt, 2007; Unruh, 2008). Nursing workload and hospital work environment variables, including culture, have a significant impact on the ability of the nurse to provide safe and appropriate care (Kane et al., 2007; Unruh, 2008). Nurse researchers are working to describe these relationships and provide guidance for effective staffing models.

While the Medicare Conditions of Participation (68 Federal Register 3435, 2003) have long required hospitals to have policies in place to ensure “adequate” nurse staffing, specific policy has lagged. With the increasing body of evidence documenting the relationship between nurse staffing and patient outcomes, several states have passed legislation requiring organizations to adopt more specific policies and practices. For example, dissatisfied with the staffing by patient acuity model legislated in the early 1990s, (Coffman, Seago, Spetz, 2002) members of the California Nurses Association successfully pressed 164 legislators to pass a prescriptive bill specifying the maximum number of patients to be assigned to a registered nurse in each patient care area (California Assembly Bill No. 394, 1999). The statute was implemented in 2004. Other states have passed legislation (ANA, 2019) with an alternative policy approach requiring hospitals to engage nurse staffing committees in the determination of appropriate staffing levels. The legislation prescribes that 60% of the committee seats are filled by direct care nurses to ensure nursing input in staffing decisions.

Nurse researchers play an important role in policy evaluation by studying the impact of policy changes.Such policies directly support nurse executives, often the decision-makers related to staffing, by offering a flexible approach to planning and budgeting nursing services. Nurse researchers play an important role in policy evaluation by studying the impact of policy changes. A study examining the effect of Texas’ staffing legislation (Texas Senate Bill 476, 2009) found that hospitals with higher staffing levels did not significantly change after the legislation and hospitals the lowest staffing levels prior to the legislation increased staffing (Jones, Bae, and Murry, 2015).

Musculoskeletal Injury Prevention

Patient transfers, lifting, and handling are physically demanding and present clear risk for both the patient and the nurse. Frequent bending and standing contributes to fatigue and may increase the risk of slips of falls. The risks are not only damaging to the health of nurses and patients, but also are costly in terms workers compensation insurance and nurse turnover. Registered nurses experience musculoskeletal injuries at a rate of 46.0 cases per 10,000 full-time workers, much higher than the rate for all occupations, 29.4 cases per 10,000 workers based on data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Survey of Occupational Injuries and Illnesses. (Dressner & Kissinger, 2018). In addition, rising obesity rates means that nurses are caring for patients who are heavier and have a higher rate of comorbid conditions. An estimated 12-18% of nurses leave the profession due to chronic back pain (Nelson & Baptiste, 2006).

Texas was the first state to have safe patient handling and movement policies enacted in legislation.The national “Handle with Care” campaign, launched by ANA in 2003 to engage members of the healthcare industry in back injury prevention, spurred advocacy efforts to change policy (de Castro, 2004). Texas was the first state to have safe patient handling and movement policies enacted in legislation. Nurses engaged in a major 2005 legislative effort in partnership with hospitals and nursing homes. Intended to improve the safety from physical injuries of both nurses and patients, SB 1525 was signed into law and took effect January 1, 2006. This law requires hospitals and nursing homes to adopt policies and procedures for the safe handling of patients that “control the risk of injury to patients and nurses associated with the lifting, transferring, repositioning, or movement of a patient.” (Texas Senate Bill 1525, 2005). Since then, 11 states have either passed laws or promulgated regulations, 10 of which require healthcare facilities to develop and implement comprehensive safe patient handling programs (Brigham, 2015). See Table for examples of these laws.

Table. Examples of State Legislation to Improve Safe Handling

|

State |

Law |

Year Passed/Implemented |

|

California |

California Labor Code Section 6403.5 |

2011 |

|

Illinois |

Illinois Public Act 97-0122 |

2011 |

|

New Jersey |

New Jersey S-1758/A-3028 |

2008 |

|

Minnesota |

Minnesota HB 712.2 |

2007 |

|

Maryland |

Maryland SB 879 |

2007 |

|

Rhode Island |

Rhode Island House 7386 and Senate 2760 |

2006 |

|

Hawaii |

Hawaii House Concurrent Resolution No. 16 |

2006 |

|

Washington |

Washington House Bill 1672 |

2006 |

|

Ohio |

Ohio House Bill 67, Section 4121.48 |

2006 |

|

New York |

New York companion bills A11484, A07836, S05116, and S08358 |

2005 |

|

Texas |

Texas Senate Bill 1525 |

2005 |

Failure to Advocate

Policies that protect nurses who advocate for patients are a vital element of safe healthcare delivery.Policies that protect nurses who advocate for patients are a vital element of safe healthcare delivery. Unfortunately, the significance of nurse advocacy in protecting patients from harm is perhaps best illustrated in an example in which advocacy failed and patients were harmed. This example represents a missed opportunity for nurses to change practice through policy. Black (2011) described what, at the time, was thought to be the largest documented patient nosocomial bloodborne pathogen exposure due to inappropriate reuse of equipment and syringes intended for single use.

While many nurses recognized the reuse practice as inconsistent with safe infection control practices, complacency among coworkers and fear of retaliation inhibited reporting of concerns. As a result, 115 patients at two endoscopy clinics were infected with the hepatitis C virus. A joint investigation by federal and state agencies revealed violation of standard infection control practices. Twenty two nurses were investigated by the Nevada State Board of Nursing for alleged violations of the Nevada Nursing Practice Act, notably failure to safeguard patients (Black, 2011). Black noted that while nurses are accountable for protecting patients from harm, often few protections exist for nurses raising patient safety concerns: “…employment at-will doctrine… places nurses who witness unsafe practices in a difficult catch-22: if they report unsafe practices, they risk losing their jobs; if they don’t, they risk losing their licenses.” (p. 28).

Advocacy and Whistleblower Protections

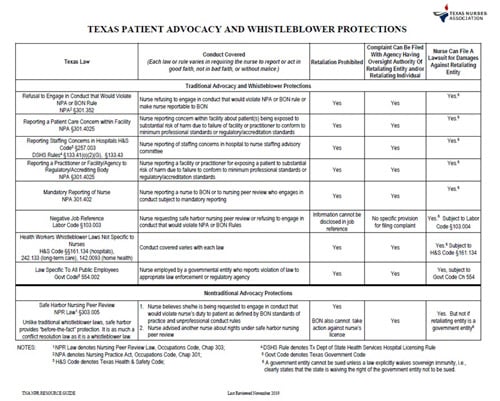

Given the outcome and scope of the outcomes of successful advocacy, and the failure to advocate discussed above, it is important to address the need for advocacy protections. This includes protections for whistleblowers. We discuss this in the context of practice in the state of Texas.

One example in Winkler County involved two nurses, Anne Mitchell and Vikki Galle, who were retaliated against for reporting unsafe medical practice. They reported first to hospital administration and then to the Texas Medical Board after their concerns were not addressed. The nurses were fired from their positions and were criminally indicted for a third-degree felony (Thomas & Willman, 2012). After Mitchell and Galle were exonerated in a jury trial, nurse advocates went to work to strengthen nurse protections. The hospital broke the law when it retaliated against the nurses for making an external report. The Department of State Health Services fined the hospital the maximum allowable amount of $1,300 (Thomas & Willman, 2012).

The Texas Nursing Practice Act includes several advocacy protections for nurses.Although policy cannot completely prevent retaliation, the Patient Advocacy Protection Bill strengthened existing protections by increasing the penalties state licensing agencies can impose. This law allows up to $25,000 per occurrence to deter retaliatory behavior (Texas Senate Bill No. 192, 2011).

The Texas Nursing Practice Act includes several advocacy protections for nurses (Texas Occupations Code Chapter 301, 303, 304, 2019). Safe Harbor Nursing Peer Review (Texas Occupations Code 303.005, 2019) protects nurses who believe in good faith that they are being requested to engage in conduct that would violate a nurse’s duty to patient as defined in the board of nursing rules on standards of professional practice and unprofessional conduct. Further protections (Texas Occupations Code, 2019) include refusal to engage in reportable conduct; reporting staffing concerns in hospitals; nurses who refuse to engage in conduct reportable to the board of nursing; and nurse reporting of concerns within a facility about patient exposure to substantial risk of harm or failure to conform to minimum professional, regulatory, or accreditation standards. Board of nursing rules outline the procedures nurses must follow to access these protections. For example, prior to 2019, nurses were required to invoke safe harbor in writing and notify the supervisor to receive the protections from employer discipline or board sanction.

As gaps in protection are identified, nurses work to address them through policy change.As gaps in protection are identified, nurses work to address them through policy change. The most recent example is a nurse who contacted the TNA practice hotline because she was retaliated against for speaking up for patient safety. Because she was in the middle of a procedure, she could not leave the patient’s bedside to invoke safe harbor in writing as required by existing law. Recognizing this gap in protection, TNA worked with Representative Stephanie Klick, RN, one of two nurses in the Texas Legislature, to pass House Bill 2410 Oral Safe Harbor (Texas House Bill No. 2410, 2019), which allows nurses to invoke safe harbor orally in situations where patient needs prevents nurses from leaving the beside to complete safe harbor forms. The Figure offers additional information about Texas patient advocacy and whistleblower protections.

Figure. Texas Patient Advocacy and Whistleblower Protections

(Reproduced with permission of Texas Nurses Association.)

Implications for Nursing Organizations and Nurses

These exemplars describe the impact of nurse advocacy to influence policy that affects nursing practice or the practice environment. The nursing profession has a long history of nurses influencing decisionmakers to make positive change in health policy. Input from nurses is the foundation of this advocacy work to identify the need for policy change and make the case for why change is needed. Often policy change involves an incremental approach that requires persistence.

Often policy change involves an incremental approach that requires persistence.An example of incremental work is the many efforts to address workplace violence. In 2010, Texas emergency department nurse Jessica Taylor authored a commentary in the American Journal of Nursing about her experience of being assaulted at work (Taylor, 2010). She encouraged all nursing associations to make violence prevention a top-priority and urged hospital leaders to adopt zero-tolerance policies.

An existing policy of enhanced criminal penalties for assaults against first responders, such as peace officers, firefighters, and emergency medical service workers (which elevated the seriousness of the offense from a misdemeanor to a felony) inspired a similar approach to deter violence against nurses. In 2011, the Texas Emergency Nurses Association with the support of the state’s Nursing Legislative Agenda Coalition (a coalition of 17 nursing organizations), supported HB 703 and SB 295 which provided for enhanced criminal penalties for assaults against nurses. Although both bills failed to pass in 2011 (Willmann, 2011), similar legislation enhancing penalties for assault of emergency department personnel passed in the next legislative session (Willmann, 2013).

Evidence about workplace violence was needed to understand the scope of the problem in Texas as well. Workplace violence is not limited to emergency departments and nurses in other settings desired similar protections. Yet, legislators had difficulty appreciating the reality of violence in healthcare settings (D. Howard, personal communication, February 5, 2015). TNA developed a strategy to obtain funding for a statewide study of health care organizations (including hospitals, free-standing emergency centers, long term care facilities and homecare agencies), to validate the extent of the problem and provide the foundation for future violence prevention initiatives. HB 2696 provided authority for the Texas Center of Nursing Workforce Studies to conduct a survey both healthcare organizations and nurses about their experiences with workplace violence (Cates, 2015).

...legislators had difficulty appreciating the reality of violence in healthcare settings.The compelling study results were published in 2016 (Texas Department of State Health Services, 2016) and the data supported efforts to pass legislation (HB 280) that funded grants for innovative approaches to reduce workplace violence in health care organizations. In 2019, legislation supported by NLAC as well as the Texas Hospital Association was proposed to establish Violence Prevention Committees within healthcare organizations (HB 2980); the effort failed (Zolnierek, 2019).

Although the organizational policy changes that result from implementation of grant programs may help protect the nurses who work the facilities awarded grant funds, widespread protections remain elusive despite a decade of advocacy. During the most recent legislative session, TNA leaders negotiated bill language with the Texas Hospital Association that would have required workplace violence prevention plans with input from direct care nurses. This bill did not pass, and work is ongoing to ensure healthcare facilities implement robust strategies that protect not only nurses but all employees.

Protections can be eroded through subsequent legislation or agency rules, and enforcement mechanisms may be weak or non-existent.In sum, the need for evaluation of policies is vital. To this end, the Texas Nurses Foundation has a dissertation grant program to support research on the impact of nursing policies in Texas. Protections can be eroded through subsequent legislation or agency rules, and enforcement mechanisms may be weak or non-existent. To ensure policies are effective, the impact on nursing practice must be evaluated to make certain policies are having the desired effect and have not created unintended consequences. Both professional nursing organizations, and individual nurses, must continue advocacy at all levels. Successful advocacy requires the identification of concerns by individual nurses, coupled with leadership and persistence of nursing organizations with strength in numbers and a policy agenda.

Conclusion

After the hard work is finished and the policy becomes how we practice, the origin stories are lost, and progress is often taken for granted. Many nurses may remember the times before cars had seatbelts and smoking in the nurse’s lounge was a common practice. It is remarkable to reflect on the first nurse practice acts and consider that those empowered nurses advanced the profession more than a decade before women even had the right to vote.

In 2020, the Year of the Nurse and Midwife, let every nurse and professional nursing organization continue the forward progress that advocacy supports.Nurses know that a culture supporting collaborative, interdisciplinary practice that encourages both identification and reporting of problems and barriers to care delivery leads to optimum patient and nurse outcomes. Protections are imperfect, but that does not diminish their importance. Protection failures represent opportunities for future advocacy.

The profession of nursing has changed significantly in the 160 years since Florence Nightingale’s day, but her words still ring true today, “Unless we are making progress in our nursing every year, every month, every week, take my word for it we are going back” (Nightingale, 1914, p. 1). In 2020, the Year of the Nurse and Midwife, let every nurse and professional nursing organization continue the forward progress that advocacy supports.

Authors

Ellen Martin, PhD, RN, CPHQ, CPPS

Email: ellenemartin@gmail.com

As Director of Practice of the Texas Nurses Association, Ellen supports nurses’ efforts to influence policy through member engagement and assistance, collaboration, and communication. She is active in policy development, actively assisting policy committees in analyzing issues and developing policy positions. Ellen began her clinical practice in neuroscience nursing and for the past 20 years has focused on healthcare quality across the continuum of care from acute care hospitals, to community-based mental health, home care, and hospice. She received an ASN from Angelo State University, a BSN and MSN from Queens University of Charlotte where she was recognized as the outstanding graduate student, and a PhD in nursing from University of Texas at Austin.

Cindy Zolnierek, PhD, RN, CAE

Email: cdzolnierek@texasnurses.org

As chief executive of the Texas Nurses Association, Cindy leads the strategic operations of the Texas Nurses Association, a professional membership organization of registered nurses that empowers Texas Nurses to advance the profession. She is active in policy development, actively negotiating legislative approaches to address nursing’s agenda. Cindy’s nursing career spans advanced practice, chief nurse executive, and academic roles. She has authored numerous publications focusing on nursing practice, advocacy, and care of persons with serious mental illness. She received a BSN from University of Detroit – Mercy, magna cum laude, an MSN in adult psychiatric-mental health nursing from Wayne State University, and a PhD in nursing from University of Texas at Austin where she was recognized as the outstanding doctoral student.

References

Aiken, L. H., Cimiotti, J. P., Sloane, D. M., Smith, H. L., Flynn, L., & Neff, D. F. (2012). Effects of nurse staffing and nurse education on patient deaths in hospitals with different nurse work environments. Journal of Nursing Administration, 42(10), Supplement: S10–S16. doi: 10.1097/01.NNA.0000420390.87789.67

Aiken, L. H., Clarke, S. P., Sloane, D. M., Lake E. T., & Cheney T. (2008). Effects of hospital care environment on patient mortality and nurse outcomes. Journal of Nursing Administration, 38(5): 223–229. doi: 10.1097/01.NNA.0000312773.42352.d7

American Nurses Association. (n.d.). The history of the American Nurses Association. Retrieved from https://www.nursingworld.org/ana/about-ana/history/

American Nurses Association. (1997). Implementing nursing's report card: A study of RN staffing, length of stay and patient outcomes. Washington, DC: American Nurses Publishing.

American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics with interpretive statements. Silver Springs, MD: American Nurses Association.

American Nurses Association. (2019). Nurse staffing advocacy. Retrieved from https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nurse-staffing/nurse-staffing-advocacy/

Black, L. M. (2011). Tragedy into policy: A quantitative study of nurses' attitudes toward patient advocacy activities. American Journal of Nursing, 111(6), 26-35. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000398537.06542.c0

Brigham, C. J. (2015). Safe patient handling U.S. enacted legislation snapshot. Retrieved from https://www.asphp.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/SPH-US-Enacted-Legislation-02222015.pdf

Brown, J. L. (2010). Texas Nurses Association. In Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved from https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/sat02

California Legislative Information. (1999). California Assembly Bill No. 394. Retrieved from http://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=199920000AB394

Cates, A. (2015). Legislative update: TNA protects nurses in 84th session. Texas Nursing, 89(3), 7-9, 17.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013). Safe patient handling and mobility. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/safepatient/default.html#safe%20patient%20handling%20legislation%20in%20the%20usa .

Cimiotti, J. P., Aiken, L. H., Sloane, D. M., & Wu, E. S. (2012). Nurse staffing, burnout, and health care–associated infection. American Journal of Infection Control, 40(6), 486-490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2012.02.029

Coffman, J., Seago, J. A., & Spetz, J. (2002). Minimum nurse-to-patient ratios in acute care hospitals in California. Health Affairs, 21(5), 53-64. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.53

de Castro, A. B. (2004). Handle with care®: The American Nurses Association’s campaign to address work-related musculoskeletal disorders. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 9(3). Retrieved from http://ojin.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/ANAMarketplace/ANAPeriodicals/OJIN/TableofContents/Volume92004/No3Sept04/HandleWithCare.html

Dressner, M. & Kissinger, S. P. (2018). Occupational injuries and illnesses among registered nurses. Monthly Labor Review. https://doi.org/10.21916/mlr.2018.27

Dunton, N., Gajewski, B., Klaus, S., & Pierson, B. (2007). The relationship of nursing workforce characteristics to patient outcomes. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 12(3). Retrieved from http://ojin.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/ANAMarketplace/ANAPeriodicals/OJIN/TableofContents/Volume122007/No3Sept07/NursingWorkforceCharacteristics.html

Jones, T., Bae, S. H., & Murry, N. (2015). Texas nurse staffing trends before and after mandated nurse staffing committees. Policy, Politics & Nursing Practice, 16(3-4), 79-96. doi.org/10.1177/1527154415616254

Kane. R. L., Shamliyan, T. A, Mueller, C., Duval, S., & Wilt, T. J. (2007). The association of registered nurse staffing levels and patient outcomes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Medical Care, 45(12), 1195-1204.

Kohn, L. T., Corrigan, J., & Donaldson, M. S. (Eds.). (2000). To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Kudzma, E. C. (2006). Florence Nightingale and healthcare reform. Nursing Science Quarterly, 19(1), 61-64. doi: 10.1177/0894318405283556

Nelson, A., & Baptiste, A. S. (2006). Evidence-based practices for safe patient handling and movement. Orthopedic Nursing, 25(6), 366-379.

Montalvo, I. (2007). The National Database of Nursing Quality IndicatorsTM (NDNQI®). The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, (12)3, Manuscript 2. doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol12No03Man02

Nightingale, F. (1860). Notes on Nursing (1969 ed.). New York, NY: Dover Publications.

Nightingale, F. (1914). Florence Nightingale to her nurses: A selection from Miss Nightingale’s addresses to probationers and nurses of the Nightingale School at St. Thomas Hospital. London: MacMillan and Company.

North Carolina Board of Nursing. (2019). Historical Information. Retrieved from https://www.ncbon.com/board-information-historical-information

Russell, K. A. (2012). Nurse practice acts guide and govern nursing practice. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 3(3), 36-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2155-8256(15)30197-6

Small, H. (2017). A brief history of Florence Nightingale and her real legacy, a revolution in public health. New York, NY: Little, Brown Book Group.

Taft, S. H., & Nanna, K. M. (2008) What are the sources of health policy that influence nursing practice? Policy Politics & Nursing Practice 9(4), 274–287. doi: 10.1177/1527154408319287.

Taylor, J. L. (2010). Workplace violence. American Journal of Nursing, 110(3), 11. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000368933.60442.41

Texas Board of Nursing. (2019). Nursing Practice Act, Nursing Peer Review, & Nurse Licensure Compact: Texas Occupations Code. Retrieved from https://www.bon.texas.gov/pdfs/law_rules_pdfs/nursing_practice_act_pdfs/NPA2019.pdf

Texas Constitution and Statutes. (2009). Texas Senate Bill No. 476. Retrieved from https://statutes.capitol.texas.gov/Docs/HS/htm/HS.257.htm

Texas Department of State Health Services. (2016). Workplace violence study. Retrieved from https://www.dshs.texas.gov/chs/cnws/Workplace-Violence-Study.aspx

Texas Legislature Online. (2005). Texas Senate Bill No. 1525. Retrieved from https://capitol.texas.gov/tlodocs/79R/billtext/pdf/SB01525F.pdf

Texas Legislature Online. (2011). Texas Senate Bill No. 192: Section 301.413(b-1). Retrieved from https://capitol.texas.gov/tlodocs/82R/billtext/html/SB00192F.HTM

Texas Legislature Online. (2019). Texas House Bill No. 2410. Retrieved from https://capitol.texas.gov/tlodocs/86R/billtext/html/HB02410F.htm

Thomas, M. B., & Willman, J. D. (2012). Why nurses need whistleblower protection. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 3(3), 19-23. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2155-8256(15)30203-9

Unruh, L. (2008). Nurse staffing and patient, nurse, and financial outcomes. American Journal of Nursing, 108(1), 62-72. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000305132.33841.92

U.S. Government Publishing Office. (2003). 68 FR 3435 - Medicare and Medicaid programs; Hospital conditions of participation: Quality assessment and performance Improvement. Retrieved from https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/FR-2003-01-24/03-1293

Wallace, N., Cropp, B., & Coles, J. (2016). Insurance companies pay the price for HAIs. Retrieved from https://infectioncontrol.tips/2016/06/15/insurance-pay-for-hais/

Willmann, J. (2011). 2011 Session: A roller coaster ride for nursing. Texas Nursing Voice, 5(3):1, 4. Retrieved from https://www.nursingald.com/uploads/publication/pdf/231/TX7_11.pdf

Willmann, J. (2013). Nursing enjoys successful session: 2013 legislative session from a nursing perspective. Texas Nursing Voice, 7(3): 1, 3-4.

World Health Organization. (2019, January 30). Executive Board designates 2020 as the “Year of the Nurse and Midwife.” Retrieved from https://www.who.int/hrh/news/2019/2020year-of-nurses/en

Zolnierek, C. (2019). It’s a wrap! How nurses advocated for their profession in the 86th legislative session. Texas Nursing, 93(3), 8-9.