Today, family caregivers help manage multiple complex health conditions. They perform increasingly complex medical/nursing tasks, including complicated procedures that would make nursing students tremble. It is imperative that nurses lead the way to support these often-overlooked members of the care team. This article examines the challenges that family caregivers face. We summarize current evidence from the AARP Survey Findings and Update to inform nurses and other providers about how to educate family caregivers through resources such as the Home Alone AllianceSM Videos and the AJN Family Caregiving Series. We discuss proactive outreach to help family caregivers manage complex care via the CARE Act and how implementation of the act offers considerations for nurses and families. The conclusion summarizes several implications for nurse leaders to support family caregivers.

Key Words: complex care, education, family caregivers, Home Alone AllianceSM, Home Alone Revisited, medical tasks, nursing tasks, nurses, nurse practitioners, teach-back, videos

In 2017, about 41 million family caregivers in the United States provided an estimated 34 billion hours of unpaid care to adults with chronic or serious health conditions.In 2017, about 41 million family caregivers in the United States provided an estimated 34 billion hours of unpaid care to adults with chronic or serious health conditions (Reinhard, Feinberg, Houser, Choula, & Evans, 2019). In addition to providing day-to-day help with personal care, half of family caregivers are performing medical/nursing tasks, such as managing medications (which may include injections or intravenous medications), performing wound care, using meters or monitors, or performing ostomy care (Reinhard, Young, Levine et al., 2019). These tasks are typically performed by registered nurses in healthcare settings. As healthcare has evolved, family caregivers are performing many such tasks at home, typically with little or no instruction, and without ongoing nursing assistance or oversight.

A recent designation by the Executive Board of the World Health Organization (WHO) has declared 2020 as the Year of the Nurse and Midwife (WHO, 2019). While there remain challenges, nurses are leading the way in several initiatives intended to support family caregivers. This article examines the challenges that family caregivers face and describes current evidence from AARP to inform nurses and other providers about how to educate family caregivers. We describe helpful resources such as the Home Alone AllianceSM Videos and the AJN Family Caregiving Series. Finally, we discuss proactive outreach to help family caregivers manage complex care via the CARE Act and how implementation of this act offers considerations for nurses and families.

The Challenges: AARP Survey Findings and Update

While there remain challenges, nurses are leading the way in several initiatives intended to support family caregivers.In 2012, the AARP Public Policy Institute and the United Hospital Fund undertook the first nationally representative, population-based online survey of family caregivers to determine what medical/nursing tasks they perform (Reinhard, Levine, & Samis, 2012). This report was updated and expanded with the release of the 2019 Home Alone Revisited: Family Caregivers Providing Complex Care report (Reinhard, Young, Levine et al., 2019).

...as task complexity and care recipient risk increased, health professional involvement also increased.Both reports collected information about seventeen medical/nursing tasks commonly performed by family caregivers. The findings from these reports offer valuable insight about the challenges necessary to support those providing care in the home. The term “medical/nursing tasks” was selected in part because family caregivers respond to “medical tasks” as a broader term than “nursing tasks” which could be perceived as something only a registered nurse can do. Table 1 details how family caregivers learned these medical/nursing tasks. “Learned on my own” was the most common response. The most common medical/nursing tasks family caregivers learned on their own were managing incontinence with disposable briefs; preparing special diets; giving enemas; using assistive devices for mobility; using durable medical equipment; and managing medications (Reinhard, Young, Levine et al., 2019).

Nurses, including nurse practitioners, were the most frequent category of healthcare professional to provide instruction.As expected, as task complexity and care recipient risk increased, health professional involvement also increased. Nurses, including nurse practitioners, were the most frequent category of healthcare professional to provide instruction. The Table 1 medical/nursing tasks are arranged in decreasing frequency by nurse instruction. Other healthcare professionals who helped family caregivers learn medical/nursing tasks included physicians; physician assistants (PA) (grouped with nurse practitioners [NP] in this survey); social workers or geriatric care managers; pharmacists; and physical and occupational therapists. Family caregivers reported learning many medical/nursing tasks at the hospital. In addition, family caregivers also mentioned medical supply technicians as persons who helped them learn medical/nursing tasks, likely in the home setting (Reinhard, Young, Levine et al., 2019).

Table 1. How Family Caregivers Learned Medical/Nursing Tasks

|

How Caregivers Learn M/N Tasks, % (n = 1,084) |

Learned on my own |

Nurse |

NP/PA |

Nurse or NP/PA |

Other health professional |

|

Home dialysis |

1 |

36 |

41 |

77 |

22 |

|

Tube feeding |

7 |

47 |

28 |

75 |

13 |

|

Suctioning |

4 |

25 |

26 |

51 |

36 |

|

IV fluids or medications |

9 |

39 |

14 |

43 |

47 |

|

Test kits |

30 |

40 |

0 |

40 |

25 |

|

Wound care |

34 |

21 |

16 |

37 |

18 |

|

Incontinence – catheters |

19 |

19 |

16 |

35 |

27 |

|

Telehealth |

33 |

13 |

13 |

26 |

26 |

|

Ostomy care |

30 |

16 |

5 |

21 |

36 |

|

Mechanical ventilators, oxygen |

21 |

13 |

7 |

20 |

47 |

|

Meters/monitors |

46 |

7 |

11 |

18 |

22 |

|

Enemas |

70 |

14 |

1 |

15 |

10 |

|

Manage medications |

54 |

6 |

8 |

14 |

22 |

|

Assistive devices |

60 |

5 |

6 |

11 |

22 |

|

Durable medical equipment |

56 |

9 |

2 |

11 |

23 |

|

Special diets |

71 |

5 |

5 |

10 |

8 |

|

Incontinence – adult briefs |

76 |

6 |

3 |

9 |

5 |

(Reinhard, Young, Levine et al., 2019; table created by authors)

Family caregivers worry about making mistakes...Family caregivers were asked what would make it easier to perform medical/nursing tasks. For complex tasks such as suctioning, mechanical ventilation, home dialysis, and urinary catheters, more and better instruction was the most common response. Family caregivers worry about making mistakes, especially when managing medications, using meters or monitors, or performing wound care (Reinhard, Young, Levine et al., 2019).

Another source of stress for family caregivers is managing pain or discomfort. Nearly seven in ten family caregivers who performed medical/nursing tasks also helped their family member manage pain or discomfort. Family caregivers reported difficulty controlling pain and concern about giving too much or too little pain medication (Reinhard, Young, Levine et al., 2019). Nurses know that performing medical/nursing tasks, such giving injections or suctioning, can cause pain or discomfort. For family caregivers, learning to perform a procedure is difficult enough; dealing with causing pain in the process can be overwhelming.

Another source of stress for family caregivers is managing pain or discomfort...Many medical/nursing tasks that family caregivers perform are considered skilled nursing tasks and would likely be covered by the Medicare home health services benefit. Visiting nurses excel at teaching family members how to help care for their family members at home (Reinhard, Given, Petlick & Bemis, 2008). However, in addition to requiring skilled nursing services or physical therapy or other services, a Medicare recipient must be homebound in order to qualify for nursing services at home. The Home Alone Revisited sample was referred to and received home health services at a relatively high rate, 38% and 44% respectively (Reinhard, Young, Levine et al., 2019) and thus would most likely have received additional instruction from visiting nurses about how to perform medical/nursing tasks. Tables 2 and 3 summarize additional information about provision of information about home healthcare disposition upon discharge for the patients (i.e., family member) in the sample of family caregivers.

Table 2. Home Healthcare

|

Before your family member was discharged, did the hospital provide you information and/or referral to home healthcare? |

Percentage |

|

No information on home health was provided |

33% |

|

Home healthcare was discussed, but my family member’s insurance wouldn’t cover it |

14% |

|

Home healthcare was discussed but my family member refused to have home care workers come to the home |

13% |

|

Home healthcare was discussed, an agency was contacted, and my family member received home healthcare |

38% |

Table 3. Hospital Discharge Settings/Care

|

After the most recent hospitalization, was your family member discharged to: |

Percentage |

|

Home (your home or your family member’s home) with agency home healthcare services |

44% |

|

Home without agency home healthcare services |

31% |

|

Nursing home for rehabilitation services |

17% |

|

Assisted living facility (return to previous residence) |

3% |

|

Other (please specify) |

5% |

(Reinhard, Young, Levine et al., 2019; tables 2 and 3 created by authors)

Home Alone Spurs the Home Alone AllianceSM Videos

The 2012 report Home Alone: Family Caregivers Providing Complex Chronic Care uncovered the complex medical/nursing tasks that family caregivers are performing with little guidance or support, leaving them feeling stressed and concerned about making a mistake (Reinhard, Levine, & Samis, 2012). In response, the AARP Public Policy Institute convened the Home Alone AllianceSM. The Home Alone AllianceSM brings together partners from the public, private, and nonprofit sectors as a catalyst for change in how healthcare organizations and professionals interface with family caregivers. At the hub of four concepts, research, outreach, convenings and resource development (Figure 1), the Home Alone AllianceSM is a focal point for coordination, stimulation and collaboration among internal and external stakeholders committed to serving the needs of family caregivers. The Home Alone AllianceSM is uniquely positioned to galvanize the input and resources of a variety of public and private entities to advance the vision of a society where family caregivers are more confident and assured in performing a range of care to others who depend on them for their care for wellness and support.

Figure 1. Home Alone Alliance Concepts

(AARP Home Alone Alliance, n.d.)

Nurses and nursing organizations are key leaders of the Home Alone AllianceSM. Home Alone AllianceSM members include the Betty Irene Moore School of Nursing at University of California (UC) Davis; the American Journal of Nursing; the Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing; the National League for Nursing (NLN); Nurses Improving Care for Healthsystem Elders (NICHE); and the New York University Rory Meyers College of Nursing.

Before developing the video series, multicultural, multilingual focus groups of family caregivers were recruited through outreach to community-based organizations.A key initiative of the Home Alone AllianceSM is the production of videos for family caregivers. The United Hospital Fund (a partner with AARP for the first Home Alone report) funded a review of training videos and determined that the target audience for available videos which demonstrate medical/nursing tasks is nursing students or home health aides. Family caregivers were not mentioned or seen in any videos demonstrating medical/nursing tasks.

Family caregivers in the focus groups requested printed materials to accompany the videos.The Home Alone AllianceSM decided that the first two video series would be about medication management and wound care. Before developing the video series, multicultural, multilingual focus groups of family caregivers were recruited through outreach to community-based organizations. Themes from the family caregiver focus groups included the emotional impact of caregiving; caregivers’ resourcefulness; lack of training on wound care; lack of information about medications; confusion about similar-looking pills; family members’ resistance to taking medications; cultural and language differences; and lack of coordination among healthcare professionals (Levine & Reinhard, 2016). Family caregivers in the focus groups requested printed materials to accompany the videos. As the new videos are developed, each is accompanied by a written guide (as a pdf) that highlights the video messages and includes additional web resources. Table 4 lists the variety of available videos.

Table 4. Home Alone AllianceSM How-To Videos

|

Collection |

Topic |

|

Managing Medications |

Hospital Discharge Planning |

|

Mobility |

Preparing Your Home for Safe Mobility |

|

Wound Care |

General Principles of Wound Care |

|

Managing Incontinence |

Managing Incontinence: How Family Caregivers Can Help |

|

Special Diets |

Nutrition Basics |

Table created by authors (AARP Home Alone Alliance, n.d.)

AJN Family Caregiving Series

Every Home Alone AllianceSM video outline is written by nurse experts and based on current research evidence.Every Home Alone AllianceSM video outline is written by nurse experts and based on current research evidence. As the nurse experts develop the topical outlines, they simultaneously work with the editor of the American Journal of Nursing (AJN) to identity topics for articles to complement the videos. The AJN articles are designed to help nurses teach family caregivers. Each article includes simple and useful instructions for nurses to reinforce with family caregivers. Each article also includes an informational tear out sheet about the medical/nursing task.

The AJN Resources to Support Family Caregivers (2019b) includes the series of videos, “Supporting Family Caregivers: No Longer Home Alone,” (AJN, 2019c) and also additional resources for nurses (AJN Professional Partners, 2019a; “State of the Science,” 2008). These resources are available online at no charge to both AJN subscribers and the public. Note that the links provided from the reference page of this article are to the webpages only, which feature multiple videos and articles with a variety of authors.

As nurses prepare family caregivers, consider the words of AJN editor and nurse, Shawn Kennedy, writing about providing care to her mother in her final days. She reflects on the increasing responsibilities of family caregivers:

I've come to learn a lot about what family caregivers do, both from my own experience and through AJN’s collaboration with AARP's Public Policy Institute—and now, in partnership with its Home Alone AllianceSM, we provide resources to help family caregivers. But are we asking too much of family caregivers? Is it too much to ask an adolescent boy to change dressings after his mother's breast surgery? Or a 90-year-old spouse to manage his wife's ostomy care and gastrostomy-tube feedings?

My mother did not need complex wound care or gastric tube feedings, but fortunately for her, my sister and I could have administered them. Why should care for those seriously ill at home be left to chance? We need to find a better way to support families and to remove the burden of providing complex nursing care from their untrained shoulders. In the interim, the best we can do is to ensure they're prepared. (Kennedy, 2019, p.7).

Home Alone Spurs the CARE Act

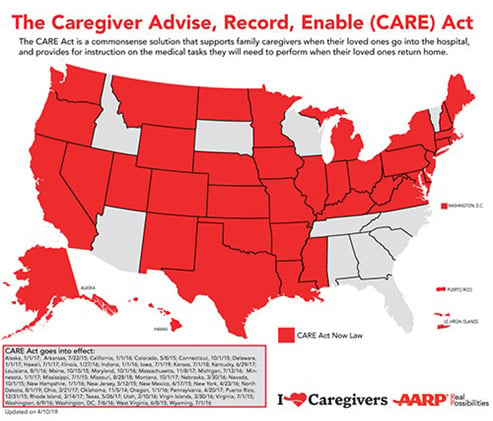

The release of the 2012 Home Alone report spoke strongly to family caregiving organizations.The release of the 2012 Home Alone report spoke strongly to family caregiving organizations. Advocates decided that legislation was needed to help family caregivers, especially in the hospital setting. The AARP State Advocacy and Strategy Integration (SASI) team used the report findings to inform model state legislation in the form of the Caregiver Advise, Record and Enable (CARE) Act (Reinhard & Ryan, 2017).

While provisions of the CARE Act vary among the states, in general, under the CARE Act:

- Hospitals must ask if a patient has a family caregiver upon inpatient admission and if so, record the family caregiver name and contact information in the medical record

- Hospitals must notify the family caregivers of discharge plans

- Family caregivers must be offered training on medical/nursing tasks they may be asked to perform.

To date 39 states plus the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands have implemented the CARE ACT. (AARP, 2020).

Figure 2. The CARE Act

Reprinted with permission. (AARP, 2019)

The Home Alone findings made sense to people...That the majority of states have passed the CARE Act in just a few years reflects the overwhelming support for family caregivers by legislators and the public. The Home Alone findings made sense to people, indicating: “Yes, this is a big problem for me or people I know.” When legislators asked if hospitals were already required to identify, notify, and instruct family caregivers, the honest answer was “no.” Throughout the country, volunteers and legislators told about their struggles providing complex care for their family members (Reinhard & Ryan, 2017).

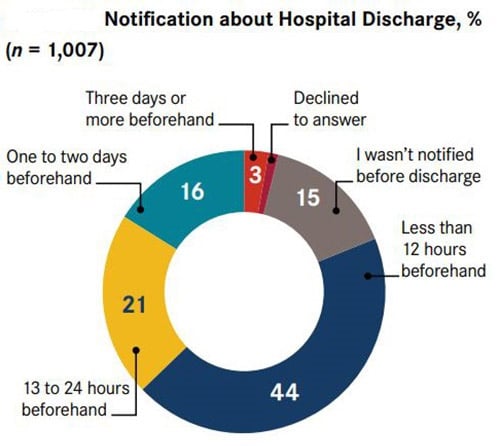

Some hospital associations and a few state nursing associations opposed the CARE Act, saying that the CARE Act provisions are already best practices and that legislation is not needed (Schaeffer & Haebler, 2019). Home Alone Revisited research tells a different story. Only about half of hospitals asked the patient to identify a family caregiver. Although two-thirds of family caregivers performing medical/nursing tasks received instruction, one-third did not. Timely notification of discharge was not done. More than eight in ten family caregivers received less than 24 hours’ notice of hospital discharge (Reinhard, Young, Levine et al., 2019).

Figure 3. Hospital Discharge Notification Timeline

(Reinhard, Young, Levine et al., 2019). Reprinted [Figure 10] with permission.

Implementing the CARE Act: Considerations for Nurses and Families

Enactment of the CARE Act legislation is just the beginning.Enactment of the CARE Act legislation is just the beginning. It is important to learn how hospitals throughout the country have implemented the CARE Act. A team of nurse researchers and policy experts is conducting site visits to study the challenges and opportunities hospitals face to put the CARE Act provisions into action (Reinhard, Young, Ryan, & Choula, 2019). Every site visit includes discussions with the hospital’s chief nursing officer. Other participant informants include front-line nurses, nurse managers, nurse educators, social workers, and physicians. Staff from the admission, registration, and electronic health record departments are also key informants, as are representatives from patient and family advisory councils. Before each site visit, separate focus groups are conducted with family caregivers of recently discharged patients (Reinhard et al., 2019). To date, the nurse researchers have conducted 25 site visits with 23 health systems and 53 hospitals in Arkansas, California, Colorado, Illinois, Michigan, Nebraska, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, Virginia, and West Virginia.

The requirement to identify family caregivers puts a spotlight on electronic health record (EHR) challenges.The requirement to identify family caregivers puts a spotlight on electronic health record (EHR) challenges. As hospitals closely examine their EHRs, which were originally designed for billing purposes, it is evident that EHR changes can better support person- and family-centered care. Hospital systems are working with EHR vendors to standardize family caregiver identification screens and to make contact information available to all clinicians. Further visibility of family caregivers occurs when their names are added to hospital room whiteboards and they are included in bedside rounds, either in person or by phone or video chat.

The designated family caregiver can serve as the main point of contact between the hospital and other family members, saving nurses the effort of repeating the same information to multiple individuals. Patients should expect to be asked to identify their family caregiver, and family caregivers should expect to be informed about treatment responses and discharge plans. The family caregiver can serve as the main point of contact before, during, and after a hospital stay. Family caregivers can help detect complications early to prevent emergency department visits and hospital readmissions.

Family caregivers can help detect complications early to prevent emergency department visits and hospital readmissions.The requirement to offer training about medical/nursing tasks for family caregivers highlights an important nursing role. Nurses demonstrate the medical/nursing task that the family caregiver will perform at home. Then the nurse asks the family members to “teach-back”, that is, to explain in their own words what they need to know or do. Whenever possible the nurse asks the family caregiver to “show-me” how to perform the medical/nursing task. This approach can help family caregivers feel more confident in performing the medical/nursing task at home after discharge. Some hospital systems have partnered with schools of nursing to allow family caregivers to learn complex medical/nursing tasks in simulation laboratories.

Implications for Nurse Leaders to Support Family Caregivers

Educating current and future nurses about how to identify and support family caregivers is essential. Nursing curricula should address both the emotional context and practical skills to help nurses better support family caregivers. Several web-based resources are outlined below.

With funding from the John A. Hartford Foundation, the National League for Nursing has developed several ACE C (Advancing Care Excellence for Caregivers) teaching strategies that are currently being piloted such as:

- Family Centered Communication Strategies in Family Caregiving

- Positive Aspects of Family Caregiving

- Supporting Millennials Providing Care for an Older Adult

- Technology Support for Caregivers of Older Adults

Nurses not only need to prepare family caregivers for the hospital discharge, they need to anticipate family caregiver questions and concerns. The Family Caregiving Institute at the Betty Irene Moore School of Nursing at UC Davis is researching the trajectory of family caregiving, caregiving technology, and the unique needs of family caregiver population (NLN, n.d.; UC Davis Health, n.d.).

Nurses Improving Care for Healthsystem Elders (NICHE) is a nursing education and consultation program designed to improve geriatric care in healthcare organizations. The NICHE (n.d.) website includes a repository of family caregiving including information about palliative care, recommended immunizations for adults over age 19, and senior citizens and home safety.

...most patients in the hospital setting need family caregiving support after discharge...In sum, most patients in the hospital setting need family caregiving support after discharge, not just those considered to be at high-risk for readmission. Regardless of patient acuity or condition, family caregivers are asked to step in as care coordinators and direct providers of medical/nursing tasks. Now is the time for nurses to step up and provide clear and supportive communication and education that includes “teach-back” and “show-me” (Nigolian & Miller, 2011).

Nurses can help alleviate the uncertainty associated with increased family caregiver responsibilities.Nurses can help alleviate the uncertainty associated with increased family caregiver responsibilities. As we celebrate the Year of the Nurse and Midwife in 2020 (WHO, 2019), let us reflect upon our past successes as leaders in the support of family caregivers, and our trusted position as providers with the skills to continue to meet the complex challenges of family-based home care. Nurses have a special duty to bring about a culture change to make this care truly person-centered, leading to the highest quality outcomes for patients and their family caregivers.

Authors

Susan C. Reinhard, RN, PhD, FAAN

Email: sreinhard@aarp.org

Susan C. Reinhard is a senior vice president at AARP, directing its Public Policy Institute, the focal point for public policy research and analysis at the state, federal, and international levels. She also serves as the chief strategist for the Center to Champion Nursing in America, a national resource center created to ensure that America has the highly skilled nurses it needs to provide care in the future. Dr. Reinhard is a nationally recognized expert in health and long-term care policy, with extensive experience in conducting, directing, and translating research to promote policy change. She is the lead author of Home Alone Revisited: Family Caregivers Providing Complex Care, which examines how family caregivers are managing medical-nursing tasks, including complex procedures that would make nursing students tremble.

Andrea Brassard, PhD, FNP-BC, FAAN

Email: abrassard@aarp.org

Andrea Brassard is a senior policy advisor at the Center to Champion Nursing in America, an initiative of AARP Foundation, AARP, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to improve healthcare through nursing and build healthier communities for everyone in America. She also provides content expertise on family caregiving initiatives.

References

AARP. (2019). The Caregiver Advise, Record, Enable (CARE) Act [Map]. Retrieved from https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2019/09/care-act-map.pdf

AARP. (2020). New state law to help family caregivers. Retrieved from https://www.aarp.org/politics-society/advocacy/caregiving-advocacy/info-2014/aarp-creates-model-state-bill.html

AARP Home Alone Alliance. (n.d.). Family caregiving how-to video series. Retrieved from https://www.aarp.org/ppi/initiatives/home-alone-alliance/

American Journal of Nursing. (2019a). Professional partners supporting diverse family caregivers across settings. Retrieved from https://journals.lww.com/ajnonline/pages/collectiondetails.aspx?TopicalCollectionId=16

American Journal of Nursing. (2019b). Resources to support family caregivers. Retrieved from https://journals.lww.com/ajnonline/Pages/caregivercollection.aspx

American Journal of Nursing. (2019c). Supporting family caregivers: No longer home alone. Retrieved from https://journals.lww.com/ajnonline/pages/collectiondetails.aspx?TopicalCollectionId=38

Kennedy, M. S. (2019). Family caregivers and the decisions they make. American Journal of Nursing, 119(3), 7. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000554010.61766.89

Levine, C., & Reinhard, S. C. (2016). “It All Falls on Me.” Family caregiver perspectives on medication management, wound care, and video instruction. AARP Public Policy Institute and United Hospital Fund. Retrieved from https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2016-08/AARP1078_FamilyCaregiver_SpotlightSep6v5.pdf

National League for Nursing. (n.d.). Family-centered communication strategies in family caregiving: ACE C Advancing Care Excellence for Caregivers. Retrieved from http://www.nln.org/professional-development-programs/teaching-resources/ace-c/teaching-strategies/family-centered-communication-strategies-in-family-caregiving

Nigolian, C. J. & Miller, K. L. (2011). Supporting family caregivers: Teaching essential skills to family caregivers. American Journal of Nursing, 111(11), 52-58. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000407303.23092.c3

Nurses Improving Care for Healthsystem Elders. (n.d.). Caregiver tools. Retrieved from https://nicheprogram.org/resources/caregiver-tools

Reinhard, S. C., Feinberg, L. F., Houser, A., Choula, R., & Evans, M. (2019, November). Valuing the invaluable 2019 update: Charting a path forward. Washington, DC: AARP Public Policy Institute. Retrieved from www.aarp.org/valuing

Reinhard, S. C., Young, H. M., Levine, C., Kelly, K., Choula, R. B., & Accius, J. (2019, April). Home Alone revisited: Family caregivers providing complex care. Washington, DC: AARP Public Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2019/04/home-alone-revisited-family-caregivers-providing-complex-care.pdf

Reinhard, S. C., Young, H. M., Ryan, E., & Choula, R. (2019, March) The CARE Act implementation: Progress and promise. Washington, DC: AARP Public Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2019/03/the-care-act-implementation-progress-and-promise.pdf

Reinhard, S. C., & Ryan, E. (2017). From Home Alone to the CARE Act: Collaboration for family caregivers. Washington, DC: AARP Public Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2017/08/from-home-alone-to-the-care-act.pdf

Reinhard, S. C., Levine, C., & Samis, S. (2012, October). Home Alone: Family caregivers providing complex chronic care. Washington, DC and New York, NY: AARP Public Policy Institute and United Hospital Fund. Retrieved from https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/research/public_policy_institute/health/home-alone-family-caregivers-providing-complex-chronic-care-rev-AARP-ppi-health.pdf

Reinhard, S. C., Given, B., Petlick, N. H., & Bemis, A. (2008) Supporting family caregivers in providing care. In R. G. Hughes (Ed.), Patient safety and quality: An evidence-eased handbook for nurses. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Schaeffer, R., & Haebler, J. (2019). Nurse leaders: Extending your policy influence. Nurse Leader, 17(4), 340-343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mnl.2019.05.010

State of the science: Professional partners supporting family caregivers. (2008). American Journal of Nursing, 108(Suppl. 9). Retrieved from https://journals.lww.com/ajnonline/toc/2008/09001

University of California Davis Health, Betty Irene Moore School of Nursing. (n.d.). Family Caregiving Institute: Overview. Retrieved from https://health.ucdavis.edu/nursing/familycaregiving/Family_Caregiving_Institute_Overview.html

World Health Organization. (2019, January 30). Executive Board designates 2020 as the “Year of the Nurse and Midwife.” Retrieved from https://www.who.int/hrh/news/2019/2020year-of-nurses/en/