Nurses strive to provide holistic care, including spiritual care, for all patients. However, in busy critical care environments, nurses often feel driven to focus on patients’ physical care, possibly at the expense of emotional and spiritual care. This study examined how Palestinian nurses working in intensive care units (ICUs) understand spirituality and the provision of spiritual care at the end of life. In this article, the author presents background studies, encouraging an increased emphasis on spiritual care, and describes the qualitative method used to study 13 ICU Gaza Strip nurses’ understanding of spiritual care. Findings identified the following themes: meaning of spirituality and spiritual care; identifying spiritual needs; and taking actions to meet spiritual needs. The author discusses the difficulty nurses had in differentiating spiritual and religious needs, notes the study limitations, and concludes by recommending increased emphasis on the provision of spiritual care for all patients.

Key Words: Spirituality, spiritual care, spiritual needs, end of life, understanding spirituality, ICU nurses, Palestine, Gaza Strip, religion, spirituality

Spiritual care, which is deeply embedded in nursing, includes respecting, caring, loving, being fully present, and supporting one’s search for meaning. Prolonging life may not be the ultimate goal of care at the end of life. Rather, goals may shift to caring, comforting, and alleviating pain rather than providing a cure (Institute of Medicine [IOM], 2015; Truog et al., 2008). This shift in goals results in an increased emphasis on other parameters of health, such as religion and spirituality, as the spiritual and religious concerns of patients may be awakened or intensified near the end of life (National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care, 2013; Lo et al., 2002). Providing spiritual care has now became an integral part of holistic care in many countries, with more attention paid to spirituality throughout the healthcare arena. When using a holistic approach to healthcare, providers meet patients' physical, social, and emotional needs, as well as spiritual needs (Murphy & Walker, 2013). Taylor (2002) has described the process of providing spiritual care as an approach used to integrate all aspects of human beings. Spiritual care, which is deeply embedded in nursing, includes respecting, caring, loving, being fully present, and supporting one’s search for meaning (Taylor, 2008).

In this article, I will present background studies encouraging an increased emphasis on spiritual care and describe the qualitative method I used to study 13 Intensive Care Unit (ICU) Gaza Strip nurses’ understanding of spiritual care. My findings identified the following themes: meaning of spirituality and spiritual care, identifying spiritual needs, and taking actions to meet spiritual needs. I will also discuss the difficulty nurses had in differentiating spiritual and religious needs, share the types of spiritual care given by these nurses, note the study’s limitations, and conclude by recommending an increased emphasis on the provision of spiritual care for all patients.

Background

There is growing evidence suggesting that provision of spiritual care has positively influenced patient coping with illness, increased quality of life, and prevented illness... There is growing evidence suggesting that provision of spiritual care has positively influenced patient coping with illness, increased quality of life, and prevented illness (Molzahn, 2007; Nelson, Rosenfeld, Breitbart, & Galietta, 2002; Tarakeshwar et al., 2006); it has also reduced depression and improved general health status and recovery (Bekelman et al., 2009). However, a few studies have found that some patients experienced negative religious coping, in that they perceived illness as a punishment from God. This negative religious coping has been associated with distress and has negatively affected quality of life (Hills, Paice, Cameron, & Shott, 2005; Sherman, Simonton, Latif, Spohn, Tricot, 2005).

During life-threating situations, when complex spiritual questions and needs arise, patients may wish to address these questions with nurses. Hence, nurses who are in direct contact with these vulnerable patients need to be knowledgeable and prepared to answer patient and family questions so as to meet their spiritual needs and address their concerns (Dhamani, Paul, & Olson, 2011). ICU nurses need to be adaptive and able to provide appropriate end-of-life care, including spiritual care (Beckstrand, Callister, & Kirchhoff, 2006).

During life-threating situations, when complex spiritual questions and needs arise, patients may wish to address these questions with nurses. In spite of being well-trained and knowledgeable in providing physical and curative care, many ICU nurses feel ill equipped to deliver appropriate care at the end-of-life (Ciccarello, 2003; Shannon, 2001). Because the Palestinian healthcare system lacks health policies related to spirituality, providing spiritual care is not completely understood. This study aimed to explore how Palestinian ICU nurses understand spirituality and the provision of spiritual care at the end of life.

Method

This qualitative study used the interpretive-descriptive approach, a method designed to answer specific questions related to practical aspects of nursing or of any specific phenomenon (Thorne, 2008; Thorne, Kirkham, & O’Flynn-Magee, 2004). Participants of this study included registered nurses who were recruited by the researcher with a face-to-face invitation in the ICUs at the two major hospitals in Gaza Strip, Palestine. The first hospital had 740 beds, of which 12 were ICU beds, and 24 ICU nurses. The second hospital had 240 beds including 12 ICU beds and a total of 18 ICU nurses. Gaza Strip has five ICUs with a total of 39 beds and 89 ICU nurses.

Participation criteria for the nurses included experience in intensive care nursing for at least one year and direct engagement in clinical practice, with care for patients at the end of life during their ICU careers. Furthermore, recruited nurses needed to indicate willingness to articulate and share their thoughts and experiences about spirituality and spiritual care.

A total of 19 nurses int he two units met the criteria. Thirteen nurses (five females and eight males) agreed to participate in the study. Participant ages ranged between 26 and 47 years with a mean of 34.3 years. Working experience ranged between 3 and 22 years, while working experience as an ICU nurse ranged between 2.5 and 20 years. Three participants had a master’s degree and the others held baccalaureate degrees in nursing. All nurses provided end-of-life care and were willing to articulate and share experience regarding spiritual care at the end of life. All nurses were Muslims, a match with the religion of their society (the great majority of people living in Gaza Strip are Muslims).

Prior to data collection, ethical approval was obtained from the Ministry of Health at Gaza Strip. All study participants were provided with information about the study. An informed, written consent was obtained from each participant. Data were collected through in-depth, face-to-face, semi-structured interviews using a pre-developed guide. Open-ended questions helped to elicit information from participants related to their experiences of spiritual care and spirituality. Examples of questions used in the interview included:

- Please, tell me what do you know about spirituality and spiritual care, and how you would define each?

- How do you recognize the spiritual needs of your patients?

- What actions do you take to meet the spiritual needs of your patients?

Each participant was privately interviewed by the researcher. I audio-taped interviews after obtaining the permission of each participant. Interview times ranged between 35-50 minutes. Prior to the interview, each nurse completed an information form requesting demographic data, such as sex, age, level of education, and experience.

Data collection and analysis occurred concurrently. I listened several times to the audiotaped interviews and transcribed them verbatim. Transcripts for interviews were read several times to gain an increased understanding of the study phenomenon at multiple levels if possible (Creswell, 2003). While reading the transcripts, the researcher coded data and organized the participants' sentences and paragraphs with similar properties into different categories.

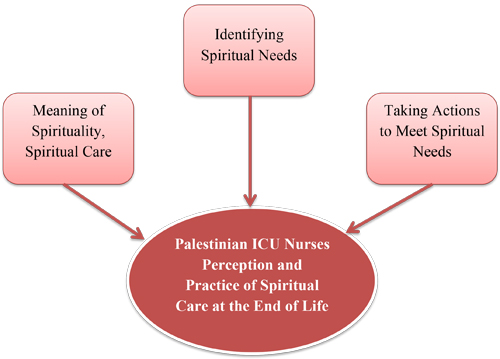

To ensure rigor and avoid bias in qualitative studies, it is advisable that at least two experts read each interview, with each identifying themes based on the data (Cohen & Crabtree, 2008; Polit & Beck, 2004). Experts then discuss findings until reaching a consensus about the themes. I asked two expert nurses in qualitative research to listen to the interviews and extract the main themes of the study. Next, we met to discuss the extracted themes until we reached consensus on the main themes of the study. The coding process helped us to extract three main themes from this data: meaning of spirituality, spiritual care; identifying spiritual needs; and taking actions to meet spiritual needs.

Findings

The three themes identified during our analysis are presented in the Figure. This section will report on each theme in turn. To protect the confidentiality of the participants, I used pseudonyms to identify participant quotes. Use of pseudonyms is common in qualitative research as it helps to present rich detailed data while maintaining respondent anonymity and confidentiality (Kaiser, 2009).

Figure. Study Themes

Palestinian ICU Nurses Perception & Practice of Spiritual Care at the End of Life

Meaning of Spirituality, Spiritual Care

For the great majority of participants, the concepts of spirituality and spiritual care were not differentiated; both concepts were very difficult for them to define. For the great majority of participants, the concepts of spirituality and spiritual care were not differentiated; both concepts were very difficult for them to define. One participant, Hassan, mentioned, "I am not sure what exactly meant with spiritual care. To me, it is to consider the religious needs of the patients."

Although those who tried to define the two concepts did not reach common agreement, most of them defined spirituality and spiritual care within the context of religion and religious healing practices. Most participants described providing spiritual care in terms of incorporating religious practices or beliefs into their daily provision of holistic nursing care. As stated by Samia, "Spirituality is religion and spiritual care involves using religious practices to help our patients getting better."

Likewise, Hani admitted that he couldn’t exactly define spirituality, noting:

To me, spirituality is believing in Allah (God). To me, spiritual care includes religiosity, belief in Allah, and religious practices in our care. We need to connect the issue of illness and wellness with our fate… Everything comes from Allah. We need to constantly remind our patients to thank Allah about everything regardless of their condition.

Hani’s words clearly reflect the tight connection between spiritual care and religion. Others also sought to define spiritual care. Ahmmed tried to define spiritual care in his own words as:

Each one of us is weak and very vulnerable during illness. Treatment is not only taking drugs… The real cure lies within the hands of Allah. Therefore, we advise our patients and their families to worship and pray to Allah to get closer to Him. We ask them to recite Quran more frequently and remind them to keep their belief and trust in Allah as this (the state of illness) is their destiny and accepting it is part of our religion. I think that this is spiritual care and that it helps our patients and improves their health.

Hala tried to define spirituality. After admitting that it was difficult; she described spirituality in this manner:

Spirituality, in all of its aspects, is well covered by our religion. Our society is mostly religious and religiosity increases during illness… While caring for such patients, we increase the use of verses from the Holy Quran and the use of religious terms. We try to remind our patients about Al-Shahadateen (confessing that there is no God but Allah and that Mohammed is his Messenger). We feel and experience that this helps to relax our patients and makes them more comfortable.

Most participants described providing spiritual care in terms of incorporating religious practices or beliefs into their daily provision of holistic nursing care. In her own words, Hala gave examples of some religious practices that she uses to meet her patients' spiritual needs.

Other participants described spiritual care as other interventions beside physical care. In fact, some did not distinguish between spiritual care and emotional or psychological care and thought that they are the same. For example, Samira described it as "the care that touches the soul or the inner part of our clients," and as the care that "gives worth to people and gives them hope and positivity about themselves."

Identifying Spiritual Needs

Communication with patients and family members, the health status and/or diagnosis of patients, close observation of the environment, and direct expression of feelings were identified as means of recognizing spiritual needs of patients. Each of these is described in more depth below

Communication with patients and family members. Participants mentioned that during their communication with their patient, they can tell which patients are in need for spiritual care. Samira said, "It is good to know about your patients' religiosity, before one starts providing spiritual care." Hothifa added that some patients or their family give some hints about the importance of religion to the patient:

When a family member tells you that the patient used to pray five times a day in the mosque and read a whole chapter of Holy Quran each day, you can tell that this patient is religious and will be in great need to fulfill his/her spiritual needs.

Hothifa's words demonstrate how nurses can assess spiritual needs by communicating with patients and/or family members.

Health status and/or diagnosis of patients. Other nurses mentioned that, from their experience, they know that patients' diagnosis and health status reflect the need for spiritual care. Sawsan said, "Through our experience, we can tell which patient is in need for spiritual care. Those who are diagnosed with terminal illnesses, such as terminal cancer and patients at the end of their lives, need more spiritual care than other patients." Nazmi shared:

Those patients who are hospitalized for a long period of time, or those who are terminally ill or dying, these are good indicators for the need for spiritual care… when there is no hope and death is imminent, spiritual care is more needed. At this time, I feel that this patient needs me to sit and talk to him/her. May be this is all he/she wants me to do at certain times.

In this quote, Nazmi recognizes the importance of spiritual care at the end of life.

Close observation of the environment. Many participants believed that the diligent observation of their patients’ words and expressions significantly made them aware of their spiritual needs. Sami said:

Once, one of my patients who could not speak was moving his right fourth finger. I knew that he was trying to say Al-tasahod (part of Muslims prayers). Immediately, I moved his bed so that he is facing Mecca (a city at Saudi Arabia where Muslims turn their faces during their prayers) and I started to say Al-tashahod. I could tell from his face that he was happy with what I did, and I could see him attempting to repeat Al-tashahod after me. This made me happy, too.

This quote by Sami reveals the importance of closely observing patients' behavior so that nurses can meet their needs. Nahla shared her experience by noting:

During one of my night shifts … I noticed one of my patients was crying. I held her hand and tried to find out why she was crying, but she cried more. I knew that she was afraid of something. I just sat near her holding her hands for few minutes. During that time, I read several verses from the Holy Quran until she stopped.

Nahla's words are a good example of how a nurse can interpret her patients' behavior and taking proper actions to meet her needs.

Direct expression of feelings. In some instances, participants mentioned that some patients or a family member directly express their needs for spiritual care. Sami mentioned, "Some patients ask us directly to pray for them. When they feel that there is no hope for them to cure, they ask us to pray for them to pass away peacefully and without pain and suffering." Similarly, Hassan mentioned:

You can tell that your patients are in need for spiritual care... Some of them ask us to pray for them, others ask to recite Quran to them or play a cassette player with Quran beside them. Some patients who are unable to talk point to the Quran, you recognize what he/she needs.

Therefore, in some instances, patients express their spiritual needs either verbally or non-verbally to their nurses.

Taking Actions to Meet Spiritual Needs

Nurses... when they feel that the treatment is futile and will not result in improving the patients’ condition, they will shift the goal of curing to the goal of comforting. Nurses who participated in this study indicated that when they feel that the treatment is futile and will not result in improving the patients’ condition, they will shift the goal of curing to the goal of comforting. They will do their best to ensure providing measures that will help in comforting their patients. They also become more attentive to the psychological and spiritual needs of the patients and their family members. Hala described how this sometimes occurs:

When it is not busy in the unit, we spend more time with them, just to listen or hold their hands. We allow family members to stay for longer periods of time. I believe that the hospital should provide some TVs for such patients who are conscious so that they can watch programs related to religion and listen to Quran.

Nurses also indicated that they would allow family members to visit more often and spend more time with the patient at the end of life. Hani said:

When it is not busy in the ICU, we allow family members to visit more frequently and stay for longer periods of time. In some instances; when it is really quiet in the ICU, especially at the night shift, we allow one family member to stay beside the patient. I think that this is very important for both the patient and the family. The patient will feel that someone is there for him/her at the time he/she needed them, just to hold his/her hand and let him/her feel that he/she is not alone. To the family members, they would feel that they did something valuable to their beloved one.

Both quotes demonstrate how nurses' goals shift from curing to caring and show how they meet the spiritual needs of patients at the end of life.

Participants mentioned that they will allow family members to bring a cassette player or MP3 to recite Quran beside the patient. Hothaifa noted:

We let the family to bring in a cassette player or similar stuff and let them play Quran beside the patient. We let family members to stay beside the patient for longer periods of time and some of them recite some versus from the Holy Quran to the patient. We do this especially when we feel that the patient’s condition started to countdown. I, myself, when I have time, recite some versus from the Holy Quran and let the patient hear my voice, even if he/she is unconscious.

Here, Hothaifa emphasized the role of religion in meeting the spiritual needs of their patients. In fact, sometimes nurses may give more care to the patient, as they feel more responsible toward this patient and provide extra effort to comfort him/her. Zaki described how this might be done:

Concerning the end of life care, we deal with all patients at the same level, especially about hygiene. This is our duty to keep him/her clean at all times. This is our duty and part of our religion. We don’t differentiate between patients at the end of life and other patients. While providing physical care to our clients, we speak to them, even if they are unconscious. We know that they hear us. We keep reminding them to remember Allah. We tell them that Allah loves them, cares about them, and doing the best for them.

Nurses recognized that in spite of the busy environment of the ICU, they can still provide spiritual care to their patients while providing physical care.

Some nurses reminded their patients and helped to prepare them for performing their prayers by washing their body parts. Hothaifa said:

We remind our patients about performing prayer, which is one of the five pillars of Islam. Once an Imam (clergy man) came to the unit, and he told us that we have to remind the patients about performing prayers since every Muslim must do his/her prayers unless he/she is unconscious. When we do so, we feel good about ourselves and feel that we did something valuable to our clients.

Once again, this quote demonstrates the entanglement of religion and spiritual care. Sa'id added the following comments to emphasize the role of prayers on spirituality:

Prayer helps patients to strengthen their faith and spirituality. It brings inner peace and harmony between soul and body. It brings calmness and reassurance to the patient and keeps him/her in peace. I really believe it helps patients to feel better.

This quote reflects the beliefs of nurses about spiritual care and how it can comfort patients.

It is not only that they help their patients to pray, but in most of the times they pray for them. Zaki commented, "Our role becomes to provide more spiritual care at this time. I usually pray for my patients during my own prayers.”

Discussion

The results of this study were consistent with the literature. Defining spirituality and spiritual care were difficult for many participants in comparable studies. Similar to the results of this study, the analysis of a study conducted by McSherry and Jamieson (2011) reported that there was some uncertainty regarding spirituality and spiritual care among participant nurses. In fact, it was difficult to define spirituality for many authors and scholars, experts in the field. A number of them mentioned that defining these terms was difficult (Lemmer, 2005); they described doing so as trying to define something that is mystical and intangible (Sawatzky & Pesut, 2005).

Some authors have described spirituality as an elusive concept that is hard to define (Narayanasamy et al., 2004). McSherry and Jamieson described spirituality as “an umbrella term because beneath the word there is a wide range of individual meanings, associations and interpretations that individuals may use to define and articulate understanding” (2011, p. 1761). The many definitions for spirituality in the literature reflect the confusion over defining this term. Rufener commented about this abundance of definitions in the literature adding that “...the varying content of these definitions can be a source of confusion to nurses as they address components of assessment, intervention, and evaluation of spirituality" (2011, p.5).

Confusion was evident in the attempts of nurses who participated in this study, in that they coupled spirituality with religion. They missed, in their definitions, the need to include several other components of spirituality and spiritual care, such as respecting, caring, loving, being fully present, and supporting one’s search for meaning (Taylor, 2008). This is not surprising as the great majority of the people who live in Gaza Strip are Muslims, and part of the Islamic doctrine is to believe in Allah and to believe in fate. The responses of our participants are congruent with many studies and definitions in that they perceived spirituality to be synonymous with religion, often using these terms interchangeably (McBrien, 2010; Swinton, 2001). Participants in other studies also perceived religious practices and beliefs to be the core principles of spirituality and spiritual care (Davis, 2006; Dhamani et al., 2011; McSherry & Jamieson, 2011).

...identifying patients' spiritual needs at the end of life often depended on nurses' observations and implicit or explicit communications of patients or their families.From the data analysis and examples shared by participants, identifying patients' spiritual needs at the end of life often depended on nurses' observations and implicit or explicit communications of patients or their families. Our participants reported that talking to patients and their families, listening to them, and observing the surrounding environment helped them to identify spiritual needs of patients. These strategies, used by participants of this study, were similar to those reported in the literature (Anderson, 2006; Dhamani et al., 2006).

In this study, spiritual interventions identified and offered by participants were primarily based on religious practices, along with a few non-religious-based interventions. Examples of religious-based interventions included praying for the patients, preparing and helping conscious patients to perform their daily prayer, allowing a family member to recite Quran beside the patient, or allowing visitors to bring in a cassette player or MP3 into the unit so the patient could listen to the Holy Quran. Examples for the non-religious interventions were allowing more visitations, longer stays for family members, and in some instances allowing a family member to stay beside the patient overnight. These results are generally congruent with the literature related to providing spiritual care practices that include religious components (Anderson, 2006; Dhamani et al., 2011; Mahlungulu & Uys, 2004; McSherry, 2007).

Literature has indicated that praying in health-related situations can facilitate the promoting of health and the sense of hope during critical times and crisis (Doucet & Rovers, 2010). Salman and Zoucha (2010) have suggested that praying will bring people closer to the divine (Allah, for Muslims). Such closeness to Allah during critical times can minimize the chance for development of anxiety, depression, and helplessness. In addition to praying, nurses mentioned that they participated in, or facilitated the recitation of Holy Quran to their patients. The literature supports such interventions. Several authors described reading from Holy Scriptures to be a source of spiritual comfort and reassurance for patients (Grundmann & Truemper, 2004; Salman & Zoucha, 2010; Schmidt & Mauk, 2004).

Other interventions mentioned by participants included listening, holding patients' hands, praying for them, and expressing respect to patients and their families. Such interventions reflect love and respect for their patients and can help to create a sense of connectedness between nurses, patients and family members, thus positively contributing to patients' and family members’ sense of comfort (Galek, Flannelly, Vane, & Galek, 2005). In fact, some authors (Puchalski, 2001), have advised nurses to be compassionate and available and to listen to patients. She further added that characteristics of compassion and being a good listener are required in order to provide spiritual care.

Limitations

A few limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the study consisted only Muslim nurses and patients. Therefore, the results cannot be assumed appropriate to other populations. It would be interesting to study people of other religions to determine whether nurses with other religious beliefs identify the same themes. The religious belief system itself may influence the thinking of other participants. Second, because the meanings of the terms spirituality and spiritual care are elusive, these concepts were difficult to assess. The assessment of these terms was based on the participants' face-to-face interviews; hence participants’ lack of anonymity when sharing their thoughts and experiences may have influenced their responses. Furthermore, data collection took a relatively long time, as it was not always possible to conduct interviews as scheduled. Several times interviews were canceled and rescheduled because participants were very busy giving critically needed care to their ICU patients and were unable to leave the patient bedside in this busy ICU environment.

Conclusion

Nurses used both communication and observation to identify spiritual needs of patients and provide relevant spiritual care.This study has shed light on how Palestinian ICU nurses understand and practice spiritual care at the end of life. The terms spirituality and spiritual care were challenging to define. Most participants defined them within the context of religion, as have participants in similar studies. Most of the participants were involved in providing spiritual care to their patients and family members. Most of the spiritual care provided was based on religious beliefs and practices, thus illustrating the importance of the role of religion in providing healthcare. Nurses used both communication and observation to identify spiritual needs of patients and provide relevant spiritual care.

This study is a first step in toward understandind how Palestinian ICU nurses describe spirituality and spiritual care interventions. Additional research is needed to explain the spiritual needs of patients with different diagnoses, to identify spiritual needs for different groups of patients, to explore how often spiritual care is provided in healthcare settings, to identify barriers to providing spiritual care, and to learn how healthcare providers can overcome barriers to providing appropriate spiritual care to their patients. Results of this study, and future studies, will guide new interventions and new health policies that can enhance nursing practice in Palestine and around the world.

Author

Nasser Abu-El-Noor, PhD, RN

E-mail: naselnoor@iugaza.edu.ps

Professor Abu-El-Noor is an Assistant Professor in the College of Nursing at the Islamic University of Gaza (IUG). Nasser joined the IUG in 1996 as a teaching assistant, after working for 10 years as a staff nurse at Ahli Arab Hospital in Gaza, with the last seven years being in the ICU. Professor Abu-El-Noor received the BSN degree from Al-Quds University, Palestine, an MSN degree in nursing administration from Marquette University, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and a doctoral degree in Health Care Policy, from the University of Akron in Ohio. Professor Abu-El-Noor has had considerable experience in working in the ICU and in dealing with patients at the end of life. During this time Nasser noticed that ICU nurses were giving most of their attention to physical care rather than attending to the other needs of their patients, including spiritual care. However, it was Nasser’s PhD study that actually initiated interest in spiritual care. This interest, combined with ICU experiences, prompted research in the area of spiritual care, so as to call the attention of healthcare providers to these unmet needs of the their patients.

© 2016 OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing

Article published January 28, 2016

References

Anderson, L. J. (2006). The “everydayness” of spirituality: Reclaiming the voice of spirituality in nursing through nurses’ stories. Master's thesis, University of Alberta, Alberta, Canada.

Beckstrand, R, L., Callister, L. C., & Kirchhoff, K. T. (2006). Providing a “good death”: Critical care nurses’ suggestions for improving end-of-life care. American Journal of Critical Care, 15(1), 38-45.

Bekelman, D. B., Rumsfeld, J. S., Havranek, E. P., Yamashita, T. E., Hutt, E., Gottlieb, S. H., . . . Kutner, J. S. (2009). Symptom burden, depression, and spiritual well-being: A comparison of heart failure and advanced cancer patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 24(5), 592-598. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0931-y

Ciccarello, G. P. (2003). Strategies to improve end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing, 22(5), 216-222.

Cohen, D. J., & Crabtree, B. F. (2008). Evaluative criteria for qualitative research in health care: Controversies and recommendations. The Annals of Family Medicine, 6(4), 331-339.

Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Davis, L. A. (2006). Hospitalized patients’ expectations of spiritual care from nurses. In S. D. Ambrose (Ed.), Religion and psychology: New research (pp. 1-38). New York: Nova Science Publishers.

Dhamani, K. A., Paul, P, & Olson, J. K. (2011). Tanzanian nurses understanding and practice of spiritual care. ISRN Nursing, 2011, 2-7. doi:10.5402/2011/534803

Doucet, M. & Rovers, M. (2010). Generational trauma, attachment, and spiritual/religious interventions. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 15(2), 93–105. doi:10.1080/15325020903373078

Galek, K., Flannelly, K. J., Vane, A., & Galek, R. M. (2005). Assessing a patient’s spiritual needs: A comprehensive instrument. Holistic Nursing Practice, 19(2), 62–69.

Grundmann, C. H. & Truemper, D. G. (2004). Christianity and its branches. In K. L. Mauk & N. K. Schmidt (Eds.), Spiritual care in nursing practice (pp. 83–108). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Hills, J, Paice, J.A., Cameron, J. R, & Shott, S. (2005). Spirituality and distress in palliative care consultation. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 8(4), 782-788.

Institute of Medicine. (2015). Dying in America: Improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Kaiser, K. (2009). Protecting respondent confidentiality in qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 19(11), 1632-1641.

Lemmer, C. (2005). Recognizing and caring for spiritual needs of clients. Journal of Holist Nursing, 23, 310-322.

Lo, B., Ruston, D, Kates, L.W., Arnold, R. M., Cohen, C. B., Faber-Langendoen, K… Working Group on Religious and Spiritual Issues at the End of Life. (2002). Discussing religious and spiritual issues at the end of life: a practical guide for physicians. JAMA, 287(6), 749-754.

Mahlungulu, S. N. & Uys, L. R. (2004). Spirituality in nursing: An analysis of the concept. Curationis, 27(2), 15–26.

McBrien, B. (2010). Nurses’ provision of spiritual care in the emergency setting - An Irish perspective. International Emergency Nursing, 18, 119-126. doi:10.1016/j.ienj.2009.09.004

McSherry, W. (2007). The Meaning of spirituality and spiritual care within nursing and health care practice: A study of the perceptions of health care professionals, patients and the public. London: Quay Books.

McSherry, W., & Jamieson, S. (2011). An online survey of nurses’ perceptions of spirituality and spiritual care. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20, 1757–1767. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03547.x.

Molzahn, A. E. (2007). Spirituality in later life: Effect on quality of life. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 33(1), 32-39.

Murphy, L. S., and Walker, M. S. (2013). Spirit-guided care: Christian nursing for the whole person. Journal of Christian Nursing, 30 (3), 144-152.

Narayanasamy, A., Clissett, P., Parumal, L., Thompson, D., Annasamy, S., & Edge. R. (2004). Responses to the spiritual needs of older people. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 48(1), 6–16.

National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. (2013). Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care (third edition). Retrieved from https://www.hpna.org/multimedia/NCP_Clinical_Practice_Guidelines_3rd_Edition.pdf.

Nelson, C. J., Rosenfeld, B., Breitbart, W., & Galietta M. (2002). Spirituality, religion, and depression in the terminally ill. Psychosomatics, 43, 213-220.

Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2004). Nursing research: Principles and methods. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Puchalski, C. M. (2001). Spirituality and health: The art of compassionate medicine. Hospital Physician, 37(3), 30–36.

Rufener, D. (2011). Inner strength in cancer survivors: The role of spirituality in establishing connectedness. Retrieved from https://kb.osu.edu/dspace/handle/1811/48938.

Salman, K. & Zoucha, R. (2010). Considering faith within culture when caring for the terminally ill Muslim patient and family. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing, 12(3), 156–163. doi:10.1097/NJH.0b013e3181d76d26

Sawatzky, R., & Pesut, B. (2005). Attributes of spiritual care in nursing practice. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 23(1), 19-33.

Schmidt, N. A. & Mauk, K. L. (2004). Spirituality as a life journey. In K. L. Mauk & N. A. Schmidt (Eds.), Spiritual Care in Nursing Practice (pp. 1-19). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Shannon, S. E. (2001). Helping families prepare for and cope with death in the ICU. In J.R. Curtis, J.R. & G. D. Rubefeld (eds.) Managing death in the ICU. (pp.165-182). New York: Oxford University Press.

Sherman, A. C., Simonton, S., Latif, U., Spohn, R.,& Tricot, G. (2005). Religious struggle and religious comfort in response to illness: Health outcomes among stem cell transplant patients. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 28(4), 359-367.

Swinton, J. (2001). Spirituality in mental health care: Rediscovering a forgotten dimension. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Tarakeshwar, N., Vanderwerker, L. C., Paulk, E., Pearce, M. J., Kasl, S. V.,& Prigerson, H. G. (2006). Religious coping is associated with the quality of life of patients with advanced cancer. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 9(3), 646-657.

Taylor, E. J. (2002). Spiritual care nursing: Theory, research, and practice. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Taylor, E. J. (2008). What is spiritual care in nursing? Findings from an exercise in content validity. Holistic Nursing Practice, 22(3), 154-159.

Thorne, S. (2008). Interpretive description. Walnut Creek, CA, USA: Left Coast Press.

Thorne, S., Kirkham, S. R., & O’Flynn-Magee, K. (2004). The analytic challenge in interpretive description. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 3(1), 1-11.

Truog, R., D., Campbell, M. L., Curtis, J. R., Haas, C. E., Luce, J. M., Rubenfeld, G. D., & Rushton, C. H. (2008). Recommendations for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: A consensus statement by the American College of Critical Care Medicine. Critical Care Medicine, 36(3), 953-963.