Public health nursing (PHN) practice is population-focused and requires unique knowledge, competencies, and skills. Early public health nursing roles extended beyond sick care to encompass advocacy, community organizing, health education, and political and social reform. Likewise, contemporary public health nurses practice in collaboration with agencies and community members. The purpose of this article is to examine evolving PHN roles that address complex, multi-causal, community problems. A brief background and history of this role introduces an explanation of the community participation health promotion model. A community-based participatory research project, Youth Substance Use Prevention in a Rural County provides an exemplar for description of evolving PHN roles focused on community health promotion and prevention. Also included is discussion about specific competencies for PHNs in community participatory health promoting roles and the contemporary PHN role.

Key words: community health promotion, community-based participatory research (CBPR), public health nursing, PHN competencies, nursing roles

[Public health nursing] roles involve collaboration and partnerships with communities and populations to address health and social conditions and problems. Public health nursing (PHN) involves working with communities and populations as equal partners, and focusing on primary prevention and health promotion (ANA, 2007). These and other distinguishing characteristics of PHN evolved in the context of historical and philosophical perspectives on health, preventive health care, and the professionalization of nursing. Specifically, these are roles that involve collaboration and partnerships with communities and populations to address health and social conditions and problems.

Public health nursing developed as a distinct nursing specialty during a time when expanding scientific knowledge and public objection to squalid urban living conditions gave rise to population-oriented, preventive health care. Public health nurses were seen as having a vital role to achieve improvements in the health and social conditions of the most vulnerable populations. Early leaders of PHN also saw themselves as advocates for these groups.

In the 21st century, public health nurses practice in diverse settings including, but not limited to, community nursing centers; home health agencies; housing developments; local and state health departments; neighborhood centers; parishes; school health programs; and worksites and occupational health programs. High-risk, vulnerable populations are often the focus of care and may include the frail elderly, homeless individuals, sedentary individuals, smokers, teen mothers, and those at risk for a specific disease.

Contemporary PHN practice, like the practice of early PHN leaders, is often provided in collaboration with several agencies and focused on population characteristics that cross institutional boundaries (Association of Community Health Nursing Education [ACHNE], 2003). PHN practice and roles are defined from,

...the perspective, knowledge base, and the focus of care, rather than by the site in which these nurses practice. Even though they are frequently employed by agencies in which direct care is provided to individuals and families, these nurses view individual and family care from the perspective of the community and/or the population as a whole (ACHNE, 2003, p. 10).

...PHN knowledge and competencies prepare nurses to take a leadership role to assess assets and needs of communities and populations... At an advanced level, PHN knowledge and competencies prepare nurses to take a leadership role to assess assets and needs of communities and populations and to propose solutions in partnership. Community- or population-focused solutions can have widespread influence on health and illness patterns of multiple levels of clients including individuals, families, groups, neighborhoods, communities, and the broader population (ACHNE, 2003).

The purpose of this article is to describe evolving roles in the specialty of public health nursing. A brief history of PHN provides a historical and philosophical background for current practice. A model for community participation with ethnographic orientation, and an exemplar of its use in a rural youth substance use prevention project, illustrates current advanced PHN practice. The article concludes with a discussion of essential PHN competencies, evidence that supports evolving PHN roles, and implications for contemporary public health nursing roles.

Brief Background and History of PHN Role

Prevention and curative care have been distinct concepts since ancient times. In Greek mythology, Hygeia was the goddess of preventive health, and her sister Panacea was the goddess of healing (Lundy & Bender, 2001). The notion of health care as healing, or treating those already sick, maintained dominance over preventive care for many centuries. During the mid-19th century however, new scientific understanding of transmission of disease enabled successful sanitation interventions that prevented disease on a large scale.

To carry preventive care forward, district nursing evolved as the first role for public health nurses, and Florence Nightingale concurrently professionalized nursing as an occupation (Brainard, 1922, 1985). Evolving PHN practice required an understanding of how culture, economics, politics, psychosocial problems, and sanitation influenced health and illness and the lives of patients and families (Fitzpatrick, 1975). Public health nursing in the United States (U.S.), England, and other countries quickly grew to include working with vulnerable populations in diverse settings including communities, homes, schools, neighborhoods, and worksites.

The new public health nursing role struggled, and continues to struggle, with appropriate interventions that would achieve quick results, but also leave lasting improvements in the population. With the advent of preventive health care, a moral tension arose between giving resources to the needy, and teaching them how to meet their own needs. Nursing of the acutely ill fits more easily into a model of one-way flow of resources from nurse to patient (Buhler-Wilkerson, 1989). The new public health nursing role struggled, and continues to struggle, with appropriate interventions that would achieve quick results, but also leave lasting improvements in the population. The Christian principle of helping those who help themselves guided this tension, but could not easily resolve it (Brainard, 1922, 1985). Public health nurses were urged to balance “wisdom and kindness” (Buhler-Wilkerson, 1989, p.32). Giving free services or free supplies to the poor was seen as creating dependency and upsetting the natural social fabric of communities. Public health nurses have addressed this moral tension over many years with innovative solutions that seek positive health outcomes, as well as advocate for vulnerable populations.

By the early 1900s, public health nursing roles extended beyond the care of the sick to encompass advocacy, community organizing, health education, and political reform (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2007). Several examples of exceptional PHN initiatives show how these roles improved the health of communities and populations. The visionary work of Lillian Wald’s Henry Street Settlement, started in New York City in 1906, evolved from finding and caring for the sick poor, to advocating and educating about the poor to other organizations. Wald expanded this mission to advocating for new federal agencies and a host of local improvements (Stanhope & Lancaster, 2011).

In the 1920s in Mississippi, Mary Osborne formed a collaborative between public health nurses and African-American (AA) lay midwives to improve perinatal mortality of AA women and babies (Lundy & Bender, 2001). In the 1960s in Detroit, Nancy Milio integrated community organizing, community decision-making, and PHN to develop a maternal-child health center that was highly accepted and even protected by the AA neighborhood during the “Detroit riots” (Milio, 1970). Public health nurses and other community professionals have continued to recognize the advantages of community participatory methods, including the potential for more effective intervention outcomes and capacity-building for long term benefit to the community (Savage et al., 2006).

Community Participatory Health Promotion Model

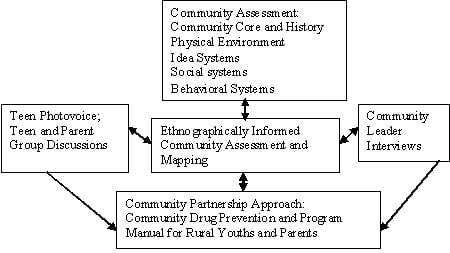

The community participation and ethnographic model (see Figure 1) is an innovative framework that demonstrates evolving public health nursing practice. It was developed, based on the work of Aronson, Wallis, O’Campo, Whitehead, and Schafer (2007a), by an inter-professional research team from the University of Virginia (UVA), Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (Virginia Tech [VT]), and Carilion Clinic (CC) (Kulbok, Meszaros, Bond, Botchwey, & Hinton, 2009) to address youth substance use prevention in a rural tobacco-growing county of Virginia. The community participation and ethnographic model builds on assumptions underlying community-based participatory research (CBPR) and encourages engagement of community members and trusted community leaders in processes from problem identification to project evaluation and dissemination. The CBPR approach is philosophically based in critical and social action theory; it builds partnerships with community members across social-economic status and focuses on community assets and resources rather than on deficits (Israel, Eng, Schulz, & Parker, 2005; Kretzmann & McKnight, 1997). CBPR seeks balance between community members and practitioners or researchers through shared leadership, co-teaching, and co-learning opportunities; it benefits from the expertise of both community members and practitioners or researchers (Anderson, Calvillo, & Fongwa, 2007; Isreal et al., 2005).

|

| Figure 1. A Community Participation and Ethnographic Model |

The community participation and ethnographic model is especially appropriate for public health nurses working with communities and populations because it provides a framework that builds upon local community knowledge. This enables public health nurses and their community partners to be sensitive to the ecological context and culture. The model is a useful guide for developing programs to promote healthy communities and health equality (Isreal et al., 2005). An ethnographically informed approach to community and population assessment and evaluation involves data collection and analysis that goes beyond adopting qualitative methods (Aronson, Wallis, O’Campo, & Schafer, 2007b). It is an approach that allows socio-cultural contexts, systems, and meaning to emerge through a collaborative process between public health nurses and community members.

Early ethnographic work in substance use prevention (Agar, 1973; Agar, 1986; Trotter, 1993) provided a foundation for the community participation and ethnographic model. Karim (1997) pointed out that the work of Agar (1973; 1986) and Trotter (1993) described the importance of acquiring local community knowledge of substance nonuse and use to provide a richer understanding of the health-related assets and needs of the community; circumstances and environment surrounding substance-related health and illness; community and population conditions; and attitudes, beliefs, and traditions directed toward substance nonuse- or use-related health risk behaviors.

Mapping enables community partners and practitioners or researchers to assess neighborhoods, cities, and/or counties to target interventions and to identify geographic trends over time. Unique strategies utilized in the community participation and ethnographic model include mapping, e.g., Geographic Information Systems (GIS), and Photovoice, e.g., picture-taking by community members and practitioners or researchers. GIS is a tool that facilitates assessment and analysis of the ecological context of a population, as well as phenomena such as youth substance nonuse and use within the community (Aronson et al., 2007b). Mapping enables community partners and practitioners or researchers to assess neighborhoods, cities, and/or counties to target interventions and to identify geographic trends over time (Shannon et al., 2008).

GIS has been used to identify unmarried teen mothers (Blake & Bentov, 2001); intervention locations for syringe distribution (Shannon et al., 2008); and minority diabetes management (Gesler et al., 2004). Using mapping methods allows community partners and practitioners or researchers to identify specific areas for both assessments and interventions (Cravey, Washburn, Gesler, Arcury, & Skelly, 2001). With community input, maps can be generated depicting areas where community members, i.e., youths, parents, and community leaders, report protective- or risk-related factors; increased or decreased substance use; and potential intervention sites.

Photovoice, or picture-taking to create a photo narrative, incorporates CBPR assumptions and enables economically and politically disenfranchised populations to express themselves with greater voice. This results in more balanced power, a sense of ownership, development of trust, potential to build capacity, and a new sensitivity to cultural preferences (Castleden, Garvin, & Nation, 2008). Photovoice uses pictures taken by community members to promote effective sharing of beliefs, knowledge, and thoughts about a given topic.

Practitioners or researchers have used Photovoice to facilitate group conversations and develop action steps... Practitioners or researchers have used Photovoice to facilitate group conversations and develop action steps (Wang & Burris, 1994) in many ways. Examples include examining quality of life with AA breast cancer survivors in rural North Carolina (Lopez, Eng, Randall-David, & Robinson, 2005); engaging youths in health promotion (Strack, Magill, & McDonagh, 2003), and building community with youths, adults, and policy-makers (Wang, Morrel-Samuels, Hutchison, Bell, & Pestronk, 2004). The goals of Photovoice in the context of the community participation and ethnographic model are to (1) enable people to record their community’s assets and strengths, as well as concerns and areas for improvement; (2) promote critical dialogue and knowledge about important issues through group discussion of photographs; and (3) reach policy-makers.

Youth Substance Use Prevention in a Rural County: An Exemplar

The Problem

Adults and youths in rural southern states have some of the highest rates of cigarette and smokeless tobacco (ST) use in the US (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2010). Adolescent tobacco use is highly correlated with use of alcohol and other drugs (Hair, Park, Ling, & Moore, 2009; Kulbok & Cox, 2002). Tobacco, alcohol, and other drug use remain pervasive problems worldwide and are responsible for a large proportion of morbidity and mortality in the US (CDC, 2010). Healthy People (HP) 2020 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [DHHS], 2010) pointed to the long-term health threat of adolescent substance use and the need to increase the proportion of adolescents who remain substance free. Many rural counties, however, have little knowledge of effective intervention strategies to prevent adolescent substance use. Healthy People 2020 (DHHS, 2010) recommended increasing population-oriented, primary prevention programs provided by community-based organizations to prevent youth tobacco, alcohol, and drug use.

The Project

A project involving the community participation and ethnographic model provides an exemplar of evolving PHN roles in community participatory health promotion. An inter-professional team, led by an advanced practice public health nurse and a human development specialist, is currently using these innovative, community participatory strategies, including GIS mapping and Photovoice, to design a substance use prevention program in a rural tobacco-growing county in the south. Public health nurses and interdisciplinary researchers created a team with youths, parents, and community leaders, to complete a comprehensive community and environmental assessment of the county, its rural ecological context and culture; and, to review evidence-based prevention programs, as the foundation for a youth substance use prevention program that will be acceptable, effective, relevant, and sustainable by the rural county.

The inter-professional research team previously worked with youths, parents, and community leaders in a rural tobacco-growing county of Virginia on two collaborative research projects focused on youth tobacco prevention (Kulbok et al., 2010; Kulbok, Meszaros, Hinton, Botchwey, & Noonan, 2009). With first-hand knowledge of the challenges faced by this rural county when attempting to prevent youth substance use, the team proposed and received funding for a project (Kulbok, Meszaros, Bond et al., 2009) based on Healthy People 2020 (DHHS, 2010) recommendations for community-based, population-oriented primary prevention. The project aims were to:

- Establish a community participatory research team (CPRT) in a rural county composed of youth, parents, and trusted community leaders;

- Conduct a community and environmental assessment with the CPRT to identify ecological, cultural, and contextual factors influencing substance-free and substance-using adolescent lifestyles;

- Evaluate the effectiveness of prevention programs with the CPRT in light of the community's ecological, cultural, and contextual dimensions, health attitudes and behaviors, and on that basis develop a tobacco, alcohol, and drug use preventive intervention for this rural tobacco-producing community; and,

- Pilot test the intervention to determine feasibility, acceptability, obtain preliminary effectiveness data, and refine the intervention for formal testing in other rural communities.

This youth substance use prevention project is currently in year three, the final stages of designing and testing a preventive intervention with the CPRT. The project, which is being implemented in stages that correspond to the aims, was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Virginia and Virginia Tech. The inter-professional project team currently includes an advanced practice public health nurse and specialists from anthropology, architecture and urban planning, epidemiology, human development, and psychology. The team also includes public health nursing and psychology doctoral students. The community members of the CPRT, during the course of the three year project, included four community leaders, twelve youths, and eight parents. All of the adult CPRT members successfully completed research ethics education required by the Instuitional Review Boards.

The CPRT completed a comprehensive community and environmental assessment of the rural county to identify assets and needs related to five assessment domains: the community’s people and history, and its physical environment, idea systems, social systems, and belief systems. In order to gather qualitative data about substance use in this county, the team completed 14 individual interviews of community leaders and five youth group interviews, with a total of 34 youths, 14 to 18 years of age. The team also completed one group interview with seven parents. Analysis of the data from these multiple sources was integrated into a comprehensive community assessment by the CPRT. Guided by the community participatory and ethnographic model, and using innovative strategies (i.e., GIS and Photovoice) described in the previous section, the team used the GIS method to visualize and analyze the assessed data related to substance use.

Innovative Strategies for Community Assessment

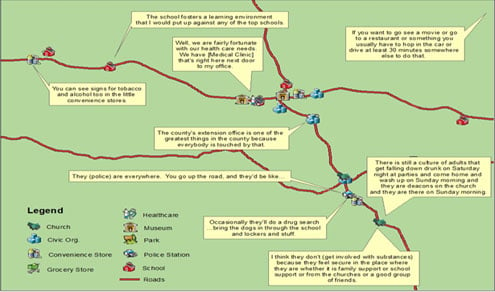

A series of community assessment maps displayed socio-demographic information about teens in the community, as well as important “teen places” that were associated with substance nonuse and use (refer to Figure 2 for one hypothetical map of “teen places” with comments from CPRT members). The data used to create these maps was collected during monthly CPRT meetings held in the county and semi-structured interviews conducted by teams of CPRT members with community leaders, youths, and parents. Interview questions were developed by the CPRT to obtain community assessment data, and identify assets and needs. Public health nurses can use GIS mapping to visualize and analyze assessment data more effectively.

|

|

Figure 2. Map of “Teen Places” and Factors Related to Youth Substance Nonuse and Use (View full size figure [pdf]) |

Photovoice is another method public health nurses can use in the community assessment process. The CPRT utilized the Photovoice method as part of their community assessment and in response to semi-structured interview questions about their rural county. Five youths received instructions to take pictures as a visual means of answering the community assessment questions. Subsequently, their pictures were displayed on “picture boards” according to the five community assessment domains, i.e., people and history, physical environment, idea systems, social systems, and belief systems, and used to facilitate discussion during group interviews with youths and parents. These “picture boards” were displayed at the end of the youth and parent group interviews to enhance each group’s description of youth substance nonuse- and use-related factors in their community.

Analysis to Date

During the timeframe that the community assessment was conducted, the CPRT used nominal group process to analyze and select six relevant effectiveness criteria for a youth substance use prevention program in their rural county. These criteria were selected from ten established criteria on substance use prevention (Winters, Fawkes, Fahnhorse, Botzet, & August, 2007). The CPRT then examined three existing substance use prevention programs with effectiveness data to assess whether they met these criteria. Selection of a prevention program that meets the chosen effectiveness criteria and fits with the ecological context and culture of their rural community is a challenging process. It is ongoing at this time and involves consideration of multi-level factors identified in the community assessment process including culture, economics, politics, and psychosocial concerns related to youth substance nonuse and use.

Although the CBPR process is challenging, the resulting local knowledge and understanding of the unique characteristics of this rural county are providing direction in the selection of a program. For example, preliminary decisions made by the CPRT include: (1) the target population for the prevention program will be middle school-aged adolescents; (2) the most feasible and desirable setting for a prevention program is the summer 4-H youth camp held in the county; and, (3) high school students, 4-H camp counselors, may be the best “instructors” for the prevention program.

This exemplar demonstrates the need for specialized knowledge, competencies, and skills utilized by public health nurses to successfully carry out complex assessments and interventions in communities. Emphasis on essential knowledge and skills in core PHN competencies and education helps to ensure that public health nurses are prepared to move their nursing practice into the future as leaders in community participatory health promotion and prevention.

Competencies for PHNs in Community Participatory Health Promoting Roles

[PHN] competencies and skills are requisite for public health nurses to serve in contemporary, evolving roles with communities and populations that face complex, multifaceted challenges... Public health nurses can acquire important knowledge, competencies, and skills to promote and protect the health of communities and populations by understanding and applying CBPR approaches. These competencies and skills are requisite for public health nurses to serve in contemporary, evolving roles with communities and populations that face complex, multifaceted challenges (Levin et al., 2008) such as public health threats that affect at-risk populations (e.g., lack of access to health care, emerging infectious diseases, poor environmental and living conditions, the epidemic of overweight and obesity, and the culture of substance use and abuse).

The nature of many threats is not unlike threats that faced PHN leaders in the early 20th century. They involve an appreciation of culture, economics, politics, and psychosocial problems as determinants of health and illness. The core competencies in PHN (Quad Council Public Health Nursing Organization [Quad Council], 2011) discussed below provide a guideline for PHN practice. By using CBPR methods, public health nurses can apply and enhance these competencies.

Analytic Assessment

Analytic assessment skills represent an important domain of PHN competencies utilized when applying community participatory health promotion strategies (Quad Council, 2011). Public health nurses should develop analytic assessment skills to pursue health promotion and prevention in partnership with communities facing complex challenges. Analytic assessment skills are used in community participatory approaches such as CBPR and provide opportunities to hear multiple voices from community insiders when conducting assessments (Andrews, Bentley, Crawford, Pretlow, & Tingen, 2007).

Public health nurses can enhance these skills by interacting with community members and using active communication to gain in-depth insights about the community’s assets and needs. Public health nurses can enhance these skills by interacting with community members and using active communication to gain in-depth insights about the community’s assets and needs. For example, when Andrews et al. (2007) used participatory methods to assess an AA population living in an impoverished neighborhood, they were assisted by community partners, advisory board members, and community health workers in interpreting the data through a series of the community forums. Therefore, they were able to reveal multi-level factors related to smoking patterns of that community by partnering with community insiders, which provided a foundation for developing effective smoking cessation interventions. In addition, as shown in the example of the CPRT work related to youth substance use prevention, public health nurses can apply analytic assessment skills by utilizing different, useful methods such as GIS, Photovoice, and individual and/or group interviews with active participation of community members.

Cultural Competence

Another important domain of PHN is cultural competence skills (Quad Council, 2011). This core ability enhances other competencies used by public health nurses when engaging in partnerships with communities and populations (Anderson & McFarlane, 2011). Cultural competence helps public health nurses understand invisible factors in the community that promote health and prevent disease, such as assets, values, strengths, and special characteristics of the communities (Anderson & McFarlane, 2011).

Public health nurses can improve their cultural competence through the use of participatory practices with diverse communities. Public health nurses can improve their cultural competence through the use of participatory practices with diverse communities (Marcus et al., 2004; McQuiston, Parrado, Martinez, & Uribe, 2005; Perry & Hoffman, 2010; Zandee, Bossenbroaek, Friesen, Blech, & Engbers, 2010). As mentioned previously, the community participation and ethnographic model is rooted in local knowledge, which can be derived from community members of differing race and ethnicity, with divergent attitudes, beliefs, and values (McGrath & Ka'ili, 2009). Listed here are several examples of research supporting acquisition of cultural competence skills using a community participatory approach:

- Perry and Hoffman’s (2010) study demonstrated that adopting a community participatory approach enabled them to develop a strategy based on American Indian youth culture to assess their level of physical activity by integrating community insiders in the process of assessment and program planning.

- In a CBPR project to reduce substance abuse in a tribal community, Thomas, Donovan, Sigo, Austin, and Marlatte (2009) provided an example of how public health nurses could attain culturally sensitive knowledge of the tradition, history, and strengths of the community by encouraging full participation of advisory councils as “cultural facilitators” in their meetings (p.4).

- McQuisiton and colleagues (2005) applied an ethnographic community participatory approach to reveal important cultural aspects, through the use of nominal group process in meetings, when assessing health disparities in a Latino population.

- Zandee et al. (2010) described how applying CBPR enabled PHN students to better understand the cultural background of the communities in which they worked and thus improve their cultural competence by partnering with community health workers.

Program Planning

Program planning skills are used in community participation approaches to optimize community health promotion and disease prevention by public health nurses (Quad Council, 2011). In program planning for community health promotion and prevention, PHNs can plan evidence-based programs by using in-depth analytic assessment skills, and can implement programs more effectively by utilizing collaborations and partnerships gained from the CBPR method (Andrews et al., 2007; Hassouneh, Alcala-Moss, & McNeff, 2011; Marcus et al., 2004; Perry & Hoffaman, 2010).

Public health nurses can develop sustainable programs and build community capacity for health promotion by taking into account the ecological context of the community from an ethnographic assessment. Public health nurses can develop sustainable programs and build community capacity for health promotion by taking into account the ecological context of the community from an ethnographic assessment (Andrews et al., 2007; Perry & Hoffaman, 2010). Perry and Hoffman (2010) demonstrated how PHNs can incorporate findings from their assessment into program development by having lively discussions and distributing information to develop the tailored program in the community. Marcus and colleagues (2004) showed how CBPR was used to develop a program to decrease HIV/AIDS in AA adolescents by creating a coalition between university-based investigators and church-based stakeholders. PHNs strategically utilized these partnerships to design and implement the program. These CBPR strategies were also utilized successfully to develop effective prevention and intervention programs (including both primary and secondary prevention programs) for cardiovascular disease prevention (Fletcher et al., 2011).

Community Dimensions of Practice

Community dimensions of practice skills focus on communication, collaboration, and linkages between public health nurses and the many stakeholders in a community (Quad Council, 2011). These skills are central to PHNs’ participation in CBPR and enable a focus on the ecological context in developing health promotion programs.

...PHNs can develop these skills by building community capacity and engaging community members and partners to design more effective, sustainable health-promoting programs. Public health nurses are able to gain these skills by creating collaborative partnerships with community leaders and stakeholders and identifying resources and solutions to problems through the CBPR method (Fletcher et al., 2011; Hassouneh et al., 2011; Marcus et al., 2004). These skills are enhanced by empowering community members to address their community’s health issues and increasing individual and community self-efficacy for health promotion throughout the CBPR process (Andrews et al., 2007; Marcus et al., 2004). Ultimately, PHNs can develop these skills by building community capacity and engaging community members and partners to design more effective, sustainable health-promoting programs.

Again, there are examples of research that used a community participatory approach to foster these community practice skills. Andrews et al. (2007) illustrated community dimensions of practice skills when partnering with community stakeholders to develop multiple levels of interventions using an ecological framework that enhanced sustainability. In another study, PHNs built partnerships with community stakeholders (Hassouneh et al., 2011) to increase trust and to better utilize community resources in applying interventions such as training. As shown in these examples, public health nurses can use CBPR to enhance partnerships and empower community members as participants by including them in the decision-making processes of assessment and program planning (Andrews et al., 2007; Hassouneh et al., 2011; Perry & Hoffaman, 2010).

Other Skills

The important skills of analytic assessment, cultural competence, program planning, and community dimensions of practice are critical for pursuing community health promotion goals as public health nurses become more widely involved in community participatory approaches. Other important competencies for the health promotion role are required for public health nurses, including communication; financial planning and management; leadership and systems thinking; policy development; and public health science (Quad Council, 2011). Public health nurses can further develop these skills by continuing to engage in community participatory practices. For example, PHN practice utilizes public health science knowledge, competencies, and skills by partnering with public health educators and researchers to develop evidence-based prevention interventions programs and thus contribute to nursing science. Community initiatives by PHNs can contribute to the development of policies based on in-depth evidence, assist community health advocates, and lead to improved long term outcomes (Fletcher et al., 2011).

The Contemporary Public Health Nursing Role

...it is essential to emphasize collaboration and partnerships with communities and populations as contemporary PHN roles evolve... Public health nursing practice at the generalist and advanced or specialist level is competency based. PHN core competencies include knowledge and skills derived from the core public health workforce competencies, which were developed by the Council on Linkages (COL) (Council on Linkages, 2010). These PHN core competencies include the three tiers of practice used in the COL competencies, i.e., Tier 1 -- the PHN generalist; Tier 2 -- the PHN specialist or manager; and, Tier 3 -- the PHN organization leader or executive level administrator (Quad Council, 2011). These core competencies are necessary to implement community participatory health promoting roles. In addition, it is essential to emphasize collaboration and partnerships with communities and populations as contemporary PHN roles evolve in the context of Healthy People 2020 (DHHS, 2010), the Patient Protection Affordable Care Act (ACA) (U.S. House of Representatives, 2010), and the National Prevention, Health Promotion, and Public Health Council (Executive Order 13544, 2010). These national initiatives provide new opportunities for emerging roles in PHN focused on community health promotion and prevention practices.

...national initiatives provide new opportunities for emerging roles in PHN focused on community health promotion and prevention practices. The community participation and ethnographic model includes important long-standing PHN processes, as well as innovative strategies that public health nurses can utilize in community assessment and prevention program development. Using PHN core competencies (Quad Council, 2011) and guided by the community participation and ethnographic model, public health nurses can empower communities and populations to become more involved in community health promotion and prevention. This empowerment can reduce health threats and increase health equity.

As the roles of public health nurses as advocates, collaborators, educators, partners, policy-makers, and researchers evolve in the area of community health promotion and prevention, greater emphasis on community participatory and ethnographic approaches in PHN education will provide benefits to students at the generalist and advanced practice levels (Zandee et al., 2010). Moreover, basic and advanced public health nursing practice roles, which emphasize inter-professional collaboration, community participatory strategies, and the importance of local knowledge to address community health problems, will continue to contribute to improved community and population health outcomes.

Acknowledgement: This project was supported by a grant from the Virginia Foundation for Healthy Youth (formerly the Virginia Youth Tobacco Settlement Foundation) 2009-2012.

Authors

Pamela A. Kulbok, DNSc, RN, PHCNS-BC, FAAN

E-mail: pk6c@virginia.edu

Dr. Kulbok is a Professor of Nursing and Public Health Sciences at the University of Virginia (UVa). She is Chair of the Department of Family, Community, and Mental Health Systems and Coordinator of the Public Health Nursing Leadership track of the MSN Program. Dr. Kulbok is the principal investigator of an inter-professional, cross-institution, community-based participatory research project funded by the Virginia Foundation for Healthy Youth to design a substance use prevention program with youth, parents, and community leaders in a rural tobacco-growing county. While at UVa, she has co-directed two advanced education nursing (AEN) training grants: the first was focused on distance education and leadership in Health Systems Management (HSM) and Public Health Nursing (PHN), the second used distance technology to prepare rural nursing leader in HSM, PHN, and Psychiatric Mental Health. Prior to her faculty appointment at UVa, she was a faculty member at the Catholic University of America and the University of Illinois at Chicago, where she was project director of community/public health nursing AEN training grants. Dr. Kulbok currently serves as the Chair of the American Nurses Association (ANA) workgroup to revise the Public Health Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice. She previously served as President-Elect and President of the ACHNE, and member and Chair of the Quad Council of Public Health Nursing Organizations. She also completed a four-year term on the ANA, Congress of Nursing Practice and Economics. Dr. Kulbok holds a BS in Nursing and an MSN in Community Health Nursing from Boston College. She earned her doctorate at Boston University and did postdoctoral work in psychiatric epidemiology at Washington University in St. Louis.

Esther Thatcher, MSN, RN

E-mail: ejm4p@virginia.edu

Ms. Thatcher is a PhD student at the University of Virginia (UVa) School of Nursing. She also received her BSN and MSN in Community/Public Health Leadership at UVa. Ms. Thatcher’s research interest is community-level interventions to prevent and reduce chronic disease in underserved communities. Her planned doctoral research is to examine the community food environment in an economically disadvantaged rural Appalachian area, to identify influences on food choices that may lead to obesity and other health conditions. Ms. Thatcher previously worked as a public health nurse in a local health department, as a care coordinator in a primary care practice, as an inpatient nurse in a hospital, and as a rural outreach nurse to Hispanic migrant farmworkers. She also volunteered in health programs in Latin America, including the Pan-American Health Organization’s Healthy Communities program. As a BSN student, Ms. Thatcher was a founding member of Nursing Students Without Borders, an organization that connects nursing students to international communities.

Eunhee Park, BSN, RN

E-mail: ep9j@virginia.edu

Ms. Park is a BSN to PhD student at the University of Virginia (UVa) School of Nursing. She is currently pursuing her Master’s degree specializing in Public Health Nursing Leadership (PHNL). Ms. Park’s research interest is youth health promotion in vulnerable populations and nursing education to enhance leadership among public health nurses. She is working with in a community based participatory research team to design a youth substance use prevention program in a rural county. Ms. Park previously worked as a staff nurse at the Pediatric Cardio Surgical Unit, Emergency Room, and Maternity Unit in Seoul National University of Hospital, South Korea. She earned her BSN degree at Kyungpook National University in South Korea.

Peggy S. Meszaros, PhD.

E-mail: meszaros@vt.edu

Dr. Peggy S. Meszaros is the William E. Lavery Professor of Human Development and Director of the Center for Information Technology Impacts on Children, Youth and Families. She has received degrees from Austin Peay State University, the University of Kentucky, and University of Maryland, College Park. During more than 30 years of work in higher education, her research interests have focused on positive youth development, technology impacts, human ecological, family, and gender issues. She has published over 90 scholarly articles, 3 books, numerous book chapters and received over six million dollars in external research grants. She is currently the Principal Investigator (PI) on the National Science Foundation funded research grant, Appalachian Information Technology Extension Services, the PI on the Virginia Healthy Youth Foundation research grant The Development and Implementation of a Family Based Substance Abuse Prevention Model for Youth Receiving Behavioral Health Services, and Co-PI on Partnering with Youth, Parents, and Community Leaders to Develop an Intervention for Substance Abuse in a Rural Community. Dr. Meszaros has received many honors and awards, including being named a Truman Scholar Mentor at Oklahoma State University and induction into the University of Kentucky Distinguished Hall of Fame.