As frontline workers on the healthcare team, nurses are positioned to witness and identify challenges faced by patients and families, challenges that might otherwise go unnoticed or be under represented. Ideas for innovative solutions to such challenges are sometimes conceived as: “If only someone could make….,” or “If I were in charge, I would…,” or “We could make this better by ….” This article describes one such situation in which the heart-wrenching issue of suboptimal pediatric pain management was tackled with the creation of a timing device for use at home by parents caring for children with postoperative pain. The author begins this article by describing the background and idea for the innovation. Next the implementation of the innovation is presented and the process and choices for the innovator are described. The author concludes that nurses are well positioned to develop solutions to patient and family care problems and have a responsibility to do so.

Key Words: nursing, innovation, intrapreneurship, entrepreneurship, business entrepreneurship, social entrepreneurship, patent, pediatric postoperative pain management, medication timing devices

Nurses are critical thinkers. They also tend to be logical, rational and analytical. Although these are important qualities for a nurse, these same qualities may cause one to dismiss or ignore creative and innovative thoughts, or those intuitive, subjective or far out ideas that nurses tend to downplay. These ideas, which pop into conscious thought out of nowhere or which may require thoughtful processing, can so often be dismissed due to lack of confidence or knowledge of what to do with them. This article seeks to empower nurses to pursue their ideas and offers suggestions for how to use these ideas for the greater good.

...historically [nurses] have seen their ideas and suggestions underutilized, undervalued or simply ignored. Nurses are uniquely positioned to notice needs for cost-effective changes, equality in access, creative new practices, streamlined workflow, and/or improved patient outcomes. With over four million, professionally active nurses in the United States (US) (Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2018) functioning across all areas of the healthcare spectrum, nurses are found on the front lines, behind the scenes, and everywhere in between. In all these roles, creative ideas are incubated. Although nurses have attempted to voice their thoughts and ideas, historically they have seen their ideas and suggestions underutilized, undervalued or simply ignored. Nurses must be empowered to pursue their innovative ideas and be given options for how best to proceed.

There are many choices for how they can proceed. Business entrepreneurship is one option. Another is that of social entrepreneurship as they become nurse entrepreneurs and intrapreneurs (Wilson, Whitaker, & Whitford, 2012). The dictionary defines an entrepreneur as “one who organizes, manages, and assumes the risks of a business or enterprise” (Merriam-Webster, 2018). According to Gilliss (2011), a social entrepreneur creates innovative ideas and usable models for social good. The focus is on improving patient care and outcomes, rather than on profit. Clara Barton, founder of the American Red Cross, is an example of a social entrepreneur. Unlike an entrepreneur, however, an intrapreneur takes creative leaps and risks, but within the security of an organization, such as a hospital. The paths of a social entrepreneur and intrapreneur are similar in their altruistic purposes, but an intrapreneur usually has less personal risk at stake.

Clara Barton, founder of the American Red Cross, is an example of a social entrepreneur. This article describes one such situation in which the heart-wrenching issue of suboptimal pediatric pain management was tackled with the creation of a timing device for use at home by parents caring for children with postoperative pain. In this article, the background and pathway of the innovation are described from its initial conception to literature reviews, studies, collaboration with staff and parents and, ultimately, implementation into clinical practice and a patent. Next, the innovation and implementation are discussed, and the process and choices chosen for the innovation are presented. Recommendations and tips for nurses seeking to develop their own ideas in an entrepreneurial spirit are offered.

The Background of the Innovation

Gillette Children’s Specialty Healthcare (Gillette Children's Specialty Healthcare, 2018) is an urban, specialty health system located in St. Paul, Minnesota. This facility specializes in care for medically complex children and adults with child-onset disabling conditions, such as cerebral palsy, spina bifida, epilepsy, and congenital syndromes. Included in the system are a 60-bed acute care hospital; six outpatient specialty clinics within the urban area; four other outpatient specialty clinics; and nine additional outreach clinics in rural areas throughout the state. Some of the surgeries performed at Gillette are extremely complex and result in substantial pain during the post-operative and post-discharge periods.

Something was definitely different at home, but what? As a telephone triage nurse in this pediatric specialty hospital, I was familiar with calls from parents struggling with their child’s post-operative pain following discharge. When I had previously worked on the inpatient unit, patients rarely experienced bouts of uncontrolled pain. Something was definitely different at home, but what? Of course, inpatient nurses had 'tools,' which the parents didn’t have: patient-controlled analgesia pumps, intravenous medications, and years of training and experience in caring for post-operative patients. Yet, it seemed to be more than that. Patients did not go home until their pain was well controlled, so why were there pain management problems at home? Parents certainly tried to follow discharge instructions and there was no lack of effort on their part. Yet there seemed to be needless suffering for some of these children, and I was overwhelmed by this thought.

Parents do face many barriers to adequate management of their child’s pain upon discharge. Several studies have recognized that the management of children’s post-operative pain at home is a challenge; and that pain is often not well controlled (Hamers & Abu-Saad, 2002; Kankkunen, Vehvilainen-Julkunen, Pietila, & Halonen, 2003; Sutters et al., 2010). Parents do face many barriers to adequate management of their child’s pain upon discharge. Some of the most common barriers include confusing medication schedules, organizing multiple medications, and monitoring side effects, in addition to dealing with the fatigue associated with caring for a post-operative child. At Gillette Children’s, parents are provided with necessary resources, such as comprehensive discharge teaching, written discharge instructions, a nurse telephone triage line, and for some, pediatric home care services. Yet even when these and other resources are available, parents report under the management of their child’s pain, due to fear of side effects and addiction and also to archaic ideas regarding children’s minimal need for pain medications (Twycross, Williams, Bolland & Sunderland, 2015).

Most parents need and want to be involved in their child’s post-operative care and pain relief. Most parents need and want to be involved in their child’s post-operative care and pain relief. The benefits of this parental participation have been found to be effective (Sng et al., 2013), even critical to optimal, post-operative pain management at home (He et al., 2015). Yet, because of the significant barriers they face, parents need more help with pain management for their children and nurses are in the most optimal position to provide this assistance (He et al., 2015).

The Idea for the Innovation

The patient's mother became confused and overwhelmed by his pain medication schedule and just stopped giving him his pain medications. One day, while working as a telephone triage nurse, I answered the phone and heard a child crying loudly on the other end. Although it took several minutes to decipher the problem, I eventually was able to ascertain that the patient’s mother was calling to ask for help with her son’s uncontrolled pain. He had been discharged two days earlier after a complex orthopedic procedure. The patient's mother became confused and overwhelmed by his pain medication schedule and just stopped giving him his pain medications. His pain was now out of control; so the mother and I quickly worked out a plan to restart his pain medications. Then, we agreed I would call back in an hour to evaluate his pain; and if his pain was not significantly improved, he would come in for evaluation. When I called back an hour later, the patient was no longer crying and his mother indicated that he was much more comfortable.

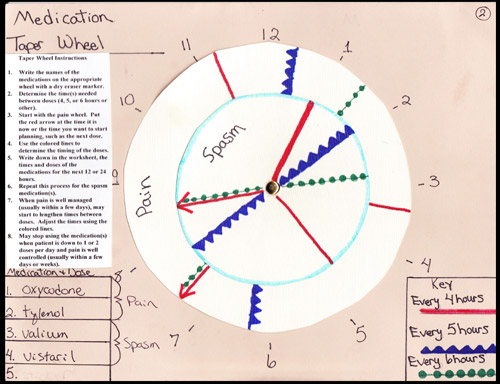

The patient’s mother and I then had time to create a longer-term plan. During our discussion and teaching, I used the face of a clock to reinforce the timing of the pain medications and instructed the mother about staying ahead of the pain by developing a daily plan. She seemed better able to understand the concept as we discussed planning out the day’s pain medications using the clock as a guide, going around the circle of hours. That night at home, I started creating the first prototype of what was to become the TyMed™ Wheel (the name is derived from “Time Your Medicine”) to help parents plan for their child’s pain medications in a simple way that anyone familiar with the face of a clock could comprehend (See Figure 1).

Figure 1. Early Version of TyMed™ Wheel (Personal copy from author)

I began with a circular background for a clock with 24 hours. Inside the circle, I put arrows that could rotate around a central midpoint like the hands on a clock. One arrow was to signify when the last dose of medication was given and the other to signify when the next dose of medication should be given. This way, a parent would always know at least when the next dose of medication was due. However, the limitations of this initial approach became apparent immediately. Most of our post-operative patients were on multiple medications for pain and spasticity, so this method seemed labor intensive and subject to confusion regarding which medication was next. Therefore, I added more arrows for different time periods (e.g., 2 hours, ...), along with colors and shapes to differentiate these times.

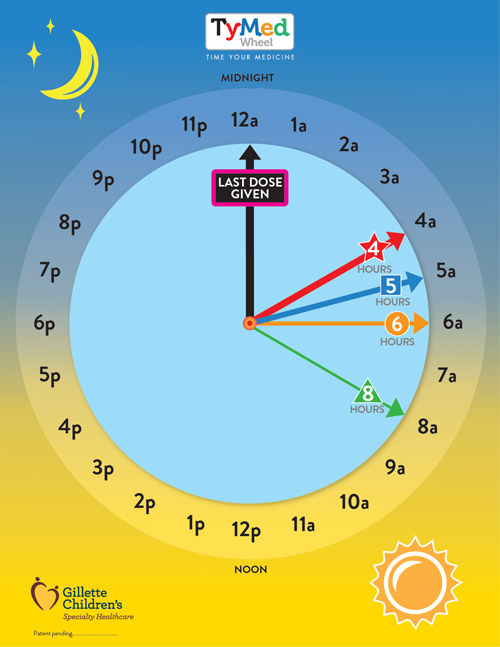

Eventually, an additional internal wheel was added so that two types of medications could be planned at the same time. Figure 2 shows the final, simplified version of the Wheel. The idea was to develop a 24-hour plan for all the pain and spasm medications and then to follow this plan one day at a time, decreasing the medications safely over time. Pain assessments, side effects, and complications would have to be monitored in conjunction with the plan. The medication management plan was to be fluid (i.e., taking into consideration alterations in daily routines); yet there was at least a plan as a starting point for parents each day.

Figure 2. Final Version of the TyMed™ Wheel (Printed with permission)

Implementation and Evaluation of the TyMed™ Wheel

...using a clock face or a 24-hour Wheel as reference point helped most parents understand medication timing in a concrete way. Once I had created several versions of wheels, I imagined using them when I worked with parents who were struggling with their children’s pain at home. I discovered that using a clock face or a 24-hour Wheel as a reference point helped most parents understand medication timing in a concrete way. It seemed to make teaching instructions easier to explain. Additionally, I realized that this would be even easier if these parents had been given this frame of reference while their children were still inpatients or in a pre-op teaching class. Had that happened, I would merely have to reinforce the teaching and concepts they had already been given, rather than introduce them to a new conceptual approach over the phone.

The wheels were positively received, but generated many questions. I began showing the wheels to co-workers at the hospital, including one of the pain researchers and the chair of the hospital pain committee. The wheels were positively received, but generated many questions. Could we use these with real patients? What would parents think? Had anyone ever tried something like this before? What about the clinicians?

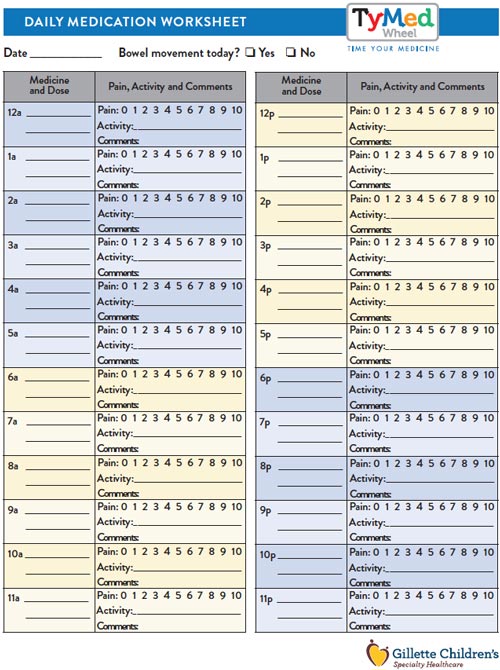

As a graduate nursing student, I took the opportunity to study this work as a thesis project. Subsequently, my idea was formalized with a literature review, a design study, and a thesis paper. During this process, several modifications were implemented and a medication worksheet was added. The Daily Medication Worksheet (Figure 3) provided a way to expand the medication timing from simply planning for the next dose to a holistic, daily pain diary.

Figure 3. The Daily Medication Worksheet (Printed with permission)

Parents of children who had undergone some of the hospital’s most complex procedures were consulted. The hospital pain committee was integral in providing content expert advice on important details of the final version... For the next couple of years, I worked with many departments and staff at the hospital to test and revise the wheel. Parents of children who had undergone some of the hospital’s most complex procedures were consulted. They offered suggestions during the first quality improvement study in 2012. In 2014, a feasibility study was conducted with parents of orthopedic surgery inpatients. These parents overwhelmingly stated they would likely use the wheel post-surgery when caring for their children at home. The nurses on the orthopedic unit agreed to this project, encouraging study participants, educating families on the use of the Wheel, and providing input on the tool and its reception by families. The hospital pain committee was integral in providing content expert advice on important details of the final version of the wheel, including the final name, aspects of the medication worksheet, and final design characteristics to ensure patient safety. With support from many hospital staff members and patients, the TyMed™ Toolkit (wheel plus worksheet) was formally created.

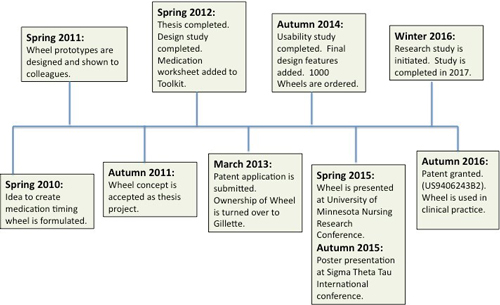

...I remained the inventor of the TyMed™ Wheel, but the hospital assumed ownership and responsibility of the intellectual property. During the development of the Toolkit, both co-workers and classmates suggested that I apply for a patent for the wheel. After repeated suggestions, I began to consider this. I investigated the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) website (USPTO, 2015a), met with a patent attorney, talked with people who had submitted patent applications and spoke with hospital administrators. I learned that this process could be long and arduous and that I had several important choices to make. I also learned about intellectual property (World Intellectual Property Organization, 2018) and how these laws impacted my choices. Finally, I decided to ask the legal counsel for the hospital to submit a patent application. This way, I remained the inventor of the TyMed™ Wheel, but the hospital assumed ownership and responsibility of the intellectual property. I thus became a social intrapreneur. I knew that the hospital was in the best position to ensure that this Toolkit was used for the patients who needed it most.

In truth, at this point in the process, I no longer had the legal ability to make independent decisions about how to proceed. I had used hospital resources and staff so that the intellectual property of my idea was now to be shared with the hospital. Legal counsel for Gillette submitted the patent search and application. It took almost three and a half years, but in 2016, the patent was granted (US9406243B2). By this time, my social intrapreneurship project, the TyMed™ Toolkit, had been incorporated as a standard of care for home pain management for complex orthopedic surgeries at Gillette.

Once the TyMed™ Wheel and Daily Med Sheet were created, it was important to evaluate the potential benefits of these tools when used by parents at home. Our team conducted an IRB-approved study. Results of this study will be reported separately.

Figure 4. Time Line for Creation of TyMed™ Wheel

The Process and Choices for the Innovator

Depending on the individual, the idea, and the situation, there may be several options for the nurse innovator. It is important to choose which path to pursue early in the process. In some instances, the path may already be predetermined. For example, a nurse who is an employee of an organization or a student of a college or university has likely signed some sort of intellectual property agreement upon employment or admission. An idea that originates at a place of employment or as part of a homework assignment may be fully or partially 'owned' by the organization or university. This is even more so if work, research, or assistance for the idea was performed with the use of property and resources of the institution. A nurse who intends to pursue an idea independently must take great care from the very beginning to separate work on this idea from any work completed through employment or school.

Choices

At the beginning of the innovation process, the nurse must make some initial decisions and ask some fundamental questions: a) Do I own this idea?, b) Do I want to make money from this idea?, and c) What is my ultimate plan/hope/dream for this idea? Answers to these questions will guide the nurse in one of the following directions: business entrepreneurship, social entrepreneurship, or social intrapreneurship.

Assuming the nurse has legitimate ownership of the idea or innovation, s/he next must decide upon the ultimate desired goal. Discussing this with a patent attorney is an excellent place to start. While attorney fees are expensive, some offer an initial meeting with a prospective client for free (LegalCORPS, 2018). In addition, there are multiple resources, such as inventor groups; state agencies or departments of commerce; university courses or workshops for inventors; and authors of published books and articles who can provide direction for the innovator (See Table 1).

Table 1. Resources for the Business Entrepreneur

|

10 Resources for Startups in 2017 |

|

|

Inventor Assistance Program |

http://legalcorps.org/inventors https://www.uspto.gov/patents-getting-started/legal-assistance-and-resources |

|

Inventor and Entrepreneur Resources |

https://www.uspto.gov/learning-and-resources/inventors-entrepreneurs-resources |

|

Inventors Network |

|

|

Medical Device Innovation Handbook |

|

|

Patent Pro Bono Program for Independent Inventors and Small Businesses |

https://www.uspto.gov/patents-getting-started/using-legal-services/pro-bono/patent-pro-bono-program |

|

Resources for Entrepreneurship |

https://carlsonschool.umn.edu/faculty-research/gary-s-holmes-center-entrepreneurship |

|

United States Patent & Trademark Office- Resources by State |

https://www.uspto.gov/learning-and-resources/patents-help/resources-state |

|

University of Minnesota Office for Technology Commercialization |

https://research.umn.edu/units/techcomm/university-inventors/resources-inventors |

Most of these resources are helpful if starting a new business or profit is the goal, but the nurse in search of a social entrepreneurial or intrapreneurial experience will need some additional resources (See Table 2). In the case of a social entrepreneur, Altman and Brinker (2016) have suggested tapping into professional organizations, such as the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses, and the American Organization of Nurse Executives for guidance. Additionally, the American Nurses Association (ANA) supports nurse innovators through its annual ANA Innovation Award (ANA, 2018). Finally, for the social intrapreneur who plans to operate primarily within the walls of his/her organization, it is vital to develop a supportive network of resources within the organization. These resources may include administration, and/or research departments or offices, as well as clinical teams, co-workers, supervisors and/or clinicians.

Table 2. Resources for the Social Entrepreneur

|

American Academy of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN) Clinical Scene Investigator (CSI) Academy |

https://www.aacn.org/nursing-excellence/csi-academy?tab=Nurses%20Leading%20Innovation |

|

American Nurses Association (ANA) |

https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/innovation-evidence/ |

|

American Organization of Nurse Executives (AONE) Care and Innovation (CIT) Program |

|

|

Resources for Social Entrepreneurship |

https://entrepreneurship.duke.edu/social-entrepreneurship/resources/ |

According to Jenkins (2018), social intrapreneurs are valuable to their employers. They help companies stay competitive and profitable and can be a public-relations boost. Even so, innovators can be dismissed due to fear of risk-taking, the opportunity cost of investment, and lack of buy-in from leadership. A nurse who wishes to pursue an intrapreneurial path without organizational support may face significant challenges, such as decreased access to financial resources, lack of a professional network, and a lack of ancillary resources that could otherwise be available, including copy machines, marketing materials, and content experts.

Developing a Supportive Network

An innovator that is fortunate enough to have a built-in support system is already a step ahead in the development process. While it’s possible for an innovative nurse to work alone successfully to bring a new product to market, collaboration with others can be a more practical strategy. Whether the concept has a global appeal or simply a departmental focus, the implementation of new concepts and processes takes a village. Ideas require support in forms, research, leadership, peers, and often, money. An innovator that is fortunate enough to have a built-in support system is already a step ahead in the development process. The innovator without a supportive culture must seek to develop one and may even have to battle adversaries to do so.

A leadership culture that supports creativity can spawn innovation. A leadership culture that supports creativity can spawn innovation. A study by Ezzat, et al. (2017) demonstrated that feedback from leadership had a direct effect on either inhibiting creativity or encouraging its activity. Carter, Donner, Lee, and Bountra (2017) noted that a team or crowd (emphasis on the group) requires collaboration and freedom in order to convert an idea into action. Environments that minimize barriers and foster ingenuity provide the basis for new ideas. Whether a nurse is developing an innovative idea within an organization or independently, s/he must work to establish formal and informal networks to help navigate the path towards the final goal, depending on what that goal may be. These include family members, inventors’ networks, co-workers, attorneys, employer committees, leadership, government organizations, and even Internet fundraising sites.

The Patent Process

In order for a patent to be granted, an idea must meet the following criteria (USPTO, 2015b):

- It must meet eligibility criteria as defined by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO).

- It must be useful.

- It must be new.

- It must be “non-obvious” meaning it cannot just be the next logical thought or process of an already existing patent.

- It must not be publicly “disclosed,” meaning already presented to the public, such as in an article or presentation.

One of the first things to do once an idea is formulated is to create a written record for the invention.

One of the first things to do once an idea is formulated is to create a written record for the invention. This includes a description of the idea, dates, timelines and even signatures of witnesses if applicable. It is necessary to document and prove originality and ownership of the idea. While it may not be necessary to obtain a patent in all cases, doing so offers competitive protection that is appealing from a business perspective. The process, however, can be costly, long, arduous and sometimes futile (USPTO, 2016). However, if successful, it can be a measure of true ingenuity and the validation needed for success.

Once the nurse innovator believes that a patent may be viable and ownership is established, the process may begin by investigating the laws, rules, and terminology involved in this complex process. Tables 1 & 2 provide resources to support the nurse innovator. One should be wary of for-profit companies that promise to help an inventor obtain a patent. While they can be of help in some instances, there are often other free or less expensive methods for submitting a patent application.

Putting an Idea into Practice

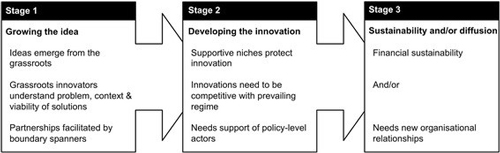

The process of taking a creative idea from thought to practice or market involves many steps and usually many years. For nurses and anyone in the healthcare industry, this process typically involves research to ensure patient safety, validity (does the product actually do what its supposed to do?) and reliability (does the product work consistently over time?). It also may involve marketing skills and business acumen, legal protections, and perhaps the creation of businesses or changes in standard procedures. Again, a supportive team helps to facilitate the creation and implementation of innovative ideas. The concept of social innovation has three stages which detail how an idea can develop into a usable product or practice change. Figure 5 outlines these stages and highlights relational features needed to implement a sustainable change in the context of the Theory of Grassroot Social Innovation (Farmer et al., 2018).

Figure 5. Theory of Grassroots Social Innovation

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 (Creative Commons, 2018)

A truly new idea may be more difficult to implement but that should not stop an attempt to do so. Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovation theory is also a helpful way to consider how an innovation becomes a new clinical practice. This theory purports that relative advantage, compatibility, complexity, trialability, and observability contribute to the likelihood that a product or idea will become part of new clinical practice (Sanson-Fisher, 2004). Therefore, to the extent that a product has an advantage over current products; is compatible with existing values; is relatively simple to implement; is able to be tested and altered and is visible to others, it is more likely to be adopted. However, the lack of these attributes should not stop an idea from moving forward. A truly new idea may be more difficult to implement but that should not stop an attempt to do so.

Osberg and Martin (2015) have studied social entrepreneurs for over 15 years. Their findings suggest that effective change is most sustainably created when two features of an existing system are altered. The first involves the economic actors and the second involves an alteration in the applied technology. Diversified customers and government are examples of new economic actors that may be added or removed by a change or new idea. Technology changes refer to substitution, creation or repurposing of existing systems. For the TyMed™ Toolkit, economic actors were altered when nursing, and not hospital administration, established methods for TyMed™ packaging and distribution. The simple, low-tech wheel costs little to produce yet can save thousands of dollars by preventing hospital readmissions, reducing side effects or effectively managing pain.

...seeing one’s idea applied and making a difference for patients and/or institutions is the ultimate reward The ultimate goal of an innovative idea is the use of this idea among the intended users. For nurses with creative solutions for solving identified problems, there can be no greater reward than seeing their creativity come to fruition. Regardless of the path taken, seeing one’s idea applied and making a difference for patients and/or institutions is the ultimate reward; it makes the difficult process so worthwhile.

Conclusion

...nurses must recognize and trust their ability to see a problem, create a solution and realize its potential. As a knowledgeable and integrated backbone of the healthcare system, nurses are positioned to identify problems and to develop solutions. Nurses owe it to themselves, and to the communities they serve, to move forward boldly with their ideas. Our patients, our communities, and the profession of nursing are betrayed if we choose not to take this initiative. Nurses have the ability to be effective partners in innovating systems, processes, and products, and can reach out to other professions if/when experiencing the limitations of their own expertise. Most importantly, nurses must recognize and trust their ability to see a problem, create a solution and realize its potential. Resources are available to guide the nurse innovator through this exciting and fulfilling adventure; an adventure that can lead to improvements in effective and safe care delivery.

Editor Notice: The purpose of this article is to share the author’s experiences throughout the process of conceptualizing and operationalizing an innovation. She also shares her experiences related to obtaining a patent and taking her idea to practice. Publication of this article does not constitute an endorsement of this product from anyone associated with either OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing or the American Nurses Association. Publication within is intended solely as a scholarly account of the author’s experiences.

Acknowledgments: The author wishes to acknowledge family, friends, co-workers, classmates and so many others who helped in a multitude of ways on this journey. Assistance from staff members in the graphic design/marketing department of the hospital was particularly instrumental in the final design of the Wheel, which was invaluable. Special thanks go to those parents who, in conjunction with caring for their postoperative children, took the time to offer suggestions and feedback on this tool. Their generosity is duly noted; this project would never have materialized without them. Finally, I would like to honor the children who demonstrated strength and courage during their recoveries and who provided the impetus for me to take the risks I could not have imagined previously. They were my inspiration all along.

Author

Celeste R. Knoff, MAN, MBA, RN, CRRN

Email: cknoff@gillettechildrens.com or celeste.r.knoff@healthpartners.com

Celeste Knoff has been a nurse for over 30 years. She has worked for Gillette Children's Specialty Healthcare since 2005 and has held several positions at the hospital including inpatient nurse, telehealth nurse, and education specialist. She is currently working in the nursing research department., casual status Ms. Knoff is also employed as the Nursing Administrator for Education and Operations at HealthPartners in Minneapolis. Celeste received her master’s degree in nursing education from St. Catherine University in St Paul, Minnesota, her master’s in business administration from the University of Nebraska-Omaha, and her bachelor’s degree in nursing from South Dakota State University. She is a Certified Rehabilitation Registered Nurse (CRRN).

References

Altman, M., & Brinker, D. (2016). Nursing social entrepreneurship leads to positive change. Nursing Management, 47(7), 28-32. DOI: 10.1097/01.NUMA.0000484476.21855.50

American Nurses Association. (2018). Innovation and evidence. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/innovation-evidence/

Carter, A. J., Donner, A., Lee, W. H., & Bountra, C. (2017). Establishing a reliable framework for harnessing the creative power of the scientific crowd. PLoS Biology, 15(2), e2001387. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2001387

Creative Commons. (2018). Attribution 4.0 International (CC by 4.0). https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Ezzat, H., Camarda, A., Cassotti, M., Agogué, M., Houdé, O., Weil, B., & Le Masson, P. (2017). How minimal executive feedback influences creative idea generation. PLoS ONE, 12(6), e0180458. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180458

Farmer, J., Carlisle, K., Dickson-Swift, V., Teasdale, S., Kenny, A., Taylor, J., … Gussy, M. (2018). Applying social innovation theory to examine how community co-designed health services develop: Using a case study approach and mixed methods. BMC Health Services Research, 18, 68. DOI: 10.1186/s12913-018-2852-0

Gillette Children’s Specialty Healthcare. (2018). About Gillette. Retrieved from https://www.gillettechildrens.org/about-gillette

Gilliss, C.L. (2011). The nurse as social entrepreneur: Revisiting our roots and raising our voices. Nursing Outlook, 59(5), 256-257. DOI:10.1016/j.outlook.2011.07.003

Hamers, J.P. & Abu-Saad, H.H. (2002) Children’s pain at home following (adeno) tonsillectomy. European Journal of Pain 6: 213–219. DOI: 10.1053/eujp.2001.0326

He, H. G., Klainin-Yobas P., Ang, E. N., Sinnappan R., Polkki, T., & Wang, W., (2015). Nurses’ provision of parental guidance regarding school-aged children’s postoperative pain management: A descriptive correlational study. Pain Management in Nursing, 16(1), 40-50. DOI: 10.1016/j.pmn.2014.03.002

Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. (2018). Total number of professionally active nurses. Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/total-registered-nurses/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

Jenkins, B. (2018). Cultivating the social intrapreneur. Stanford Social Innovation Review. Retrieved from https://ssir.org/articles/entry/cultivating_the_social_intrapreneur

Kankkunen P, Vehvilainen-Julkunen K, Pietila A.M., Halonen, P.M. (2003). Parents’ perceptions of their 1–6-year-old children’s pain. European Journal of Pain 7: 203–211. DOI: 10.1016/S1090-3801(02)00100-3

LegalCORPS. (2018). Inventors. Retrieved from http://legalcorps.org/inventors

Merriam-Webster. (2018). Definition of entrepreneur. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/entrepreneur

Osberg, S.R., & Martin, R.L. (2015). Two keys to sustainable social enterprise. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2015/05/two-keys-to-sustainable-social-enterprise

Sanson-Fisher, R. W. (2004). Diffusion of innovation theory for clinical change. Medical Journal of Australia, 180, S55-S56. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2004/180/6/diffusion-innovation-theory-clinical-change

Sng, Q. W., Taylor, B., Liam, J. L., Klainin-Yobas, P., Wang, W. & He, H. G. (2013). Postoperative pain management experiences among school-aged children: a qualitative study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 22: 958–968. DOI: 10.1111/jocn.12052

Sutters, K., Miaskowski, C., Holdridge-Zeuner, D., Waite, S., Paul, S., Savedra, M. … Mahoney, K. (2010) A randomized clinical trial of the efficacy of scheduled dosing of acetaminophen and hydrocodone for the management of postoperative pain in children following tonsillectomy. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 26(2), 95-103. DOI: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181b85f98

Twycross, A. M., Williams, A. M., Bolland, R. E., & Sunderland, R. (2015). Parental attitudes to children’s pain and analgesic drugs in the United Kingdom. Journal of Child Health Care, 19(3), 402-411. DOI: 10.1177/1367493513517305

United States Patent and Trademark Office. (2015a). General information concerning patents. https://www.uspto.gov/patents-getting-started/general-information-concerning-patents

United States Patent and Trademark Office. (2015b). What can be patented? Retrieved from https://www.uspto.gov/patents-getting-started/general-information-concerning-patents#heading-4

United States Patent and Trademark Office. (2016). U.S. patent statistics chart. https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/ac/ido/oeip/taf/us_stat.htm

Wilson, A., Whitaker, N., & Whitford, D. (2012) Rising to the challenge of healthcare reform with entrepreneurial and intrapreneurial nursing initiatives. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing 17(2):5. DOI: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol17No02Man05

World Intellectual Property Organization. (2018). What is intellectual property? Retrieved from http://www.wipo.int/about-ip/en/