American communities are in crisis due to the alarming frequency of gun violence during the last two decades. While it can be argued that the country is no more at risk of gun violence than at other times in history, technological advancement has failed to ensure any breakthroughs to curb the prevalence of violence in American culture. Nurses are trusted healthcare professionals well-positioned within communities to promote awareness, education, and lead intervention strategies to mobilize community resources to foster firearm injury prevention. However, nurses are ill-prepared to advocate for policy changes to bridge gaps in firearm safety regulations and promote the critical interdisciplinary collaboration necessary to develop comprehensive approaches to reduce firearm violence. This paper aims to provide nurses with fundamental knowledge related to strategic models that may help engage communities in meaningful, sustainable change to improve firearm safety and prevent firearm violence across the country.

Key Words: Safe Gun Storage, injury prevention, Public health, School Safety, Nurse's Role, Patient Advocacy, firearms, Gun violence

Adopting a harm prevention strategy may be a targeted approach to promote firearm safety...The year 2020 brought more to America than the COVID-19 pandemic, it saw the country reach an alarming and violent milestone. Among children ages 1-17, unintentional injury had been the leading cause of death for decades, a designation that confers some hope since it alludes to the possibility of prevention through safety practices. Yet, for the first time since the statistics have been collected, firearm violence became the leading cause of death in children, surpassing motor vehicle accidents (Goldstick et al., 2022; Rostron, 2018). This grim reality should sound an alarm signaling a critical public health crisis that firearm-related deaths cause a reported 84,000 nonfatal injuries and over 45,000 fatalities annually in the United States (Centers for Disease Controls and Prevention, 2023; Davis et al., 2022). Pervasive violence has become a feature of American culture, robbing families of future generations and dismantling the safety of our communities, and only recently have states declared safety as a right rather than a privilege in legislation (Office of Governor Gavin Newsom, 2023)

As the most trusted health professionals, nurses are well-positioned to lead efforts that employ a multifaceted approach to address the complex social, economic, and political factors contributing to firearm violence (Saad, 2020). Although highly educated, nurses lack fundamental knowledge, communication skills, and clinical training to adequately engage with patients and families to design and lead policy efforts. Adopting a harm prevention strategy may be a targeted approach to promote firearm safety, screen for firearm violence, and advocate for evidence-based policies to protect public health. This paper aims to explore the use of a harm reduction model as a framework to provide nurses with actionable strategies to advocate for and implement firearm safety interventions.

Drivers of firearm injury

A firearm is defined as “Any weapon (including a starter gun) which will or is designed to or may readily be converted to expel a projectile by the action of an explosive; the frame or receiver of any such weapon; any firearm muffler or firearm silencer; or any destructive device.” (Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, 2023). This paper is focused on issues related to a class of firearms known as guns. There are more guns than people in the United States by almost 100 million, yet, safety behaviors of firearm owners have not been the focus of national research (AFFIRM at The Aspen Institute, n.d.). Two decades of legislative restrictions imposed by the Dickey Amendment prevented any funding to understand patterns of gun possession, use, and safety, strictly prohibiting the CDC from using its funding "to advocate or promote gun control," preventing research examining gun violence in the United States (Rostron, 2018). In 2020, the legislation was finally reversed, and the limited available data reveal the paramount need to focus public health on improving safety behaviors related to gun violence.

There are many reasons for firearm use and a long history of their presence in American society.There are many reasons for firearm use and a long history of their presence in American society. What has changed is the access to a wide variety of legal firearms available to most citizens, the severity of the harm they may impose, and the availability of ammunition. While the interpretation of Second Amendment rights to protect the private rights of individuals to keep and bear arms or the right that it can be exercised only through militia organizations like the National Guard is debatable, legal access to firearms is possible in every state with varying age minimum restrictions (18-21) and background checks as requirements (Everytown Research & Policy, 2023; Library of Congress, 2023). Formal gun safety training is available online and in person through a plethora of agencies; however, only two-thirds of gun owners report having undergone training (AFFIRM at The Aspen Institute, n.d.; NRA Explore, n.d.). There is no federal policy that requires gun safety training or safe storage requirements, hence, only a reported forty-six percent of firearms are stored safely (Ramchand, 2022).

Safe storage is defined as unloaded firearms stored in a locked cabinet, safe, gun vault or storage case, in a location inaccessible and hidden from the view of children (Ramchand, 2022; Sandy Hook Promise, n.d.). Unloaded firearms should also be secured with a gun-locking device that renders the firearm inoperable and disassembled, parts should be securely stored in separate locations (Ramchand, 2022; Sandy Hook Promise, n.d.). Safe storage also applies when any person prohibited from possessing a gun is present in the gun owner’s home, including convicted felons, those convicted of domestic violence, and those with certain mental health conditions are present in a home with a firearm (Schacter, 2023). An added layer of protection is in the form of Extreme Risk Protection Orders (ERPO), also known as “red-flag laws,” which allow family members or law enforcement to petition a judge to remove a firearm from the environment of a person deemed at risk of harming themselves or others (American Academy of Pediatrics, n.d.).

As of 2021, nineteen states and the District of Columbia have passed ERPO laws (American Academy of Pediatrics, n.d.; UC Davis Health News, n.d.). No safety provision is fool-proof, but they serve as important deterrents and devices that prevent access to the firearm.

Conceptualizing a Working Harm Reduction Model for Firearm Safety

Protecting children from injury due to gun violence is a leading public health priority that demands a comprehensive approach to prevention. The harm reduction model was developed in the 1980s and initially designed for adults with substance abuse for whom abstinence is not feasible (Canadian Pediatric Society, 2008). Outcomes demonstrated that the applied model was able to reduce morbidity and mortality associated with risky health behaviors considerably and has since been adopted to address a number of issues, including the overuse of opioids, sexual behaviors, HIV, alcohol, and tobacco use in adults and adolescents (Canadian Pediatric Society, 2008; Ford et al., 2019; Hawk et al., 2017; Parkes et al., 2022; Watts et al., 2023).

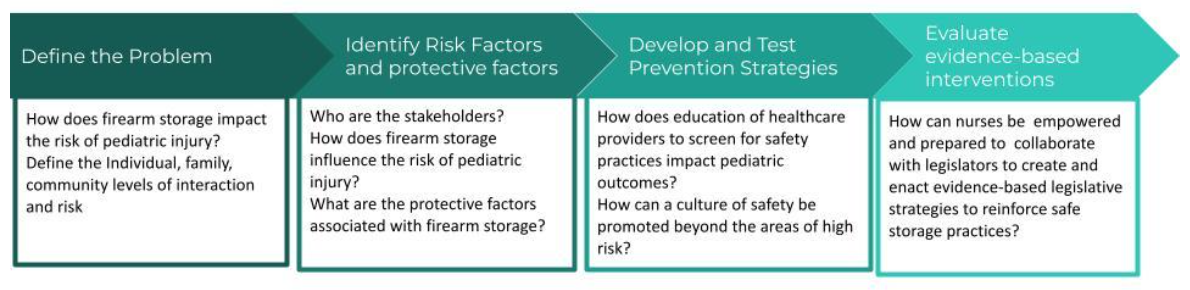

The application of a harm reduction model would be appropriate to address similar challenges related to the risk of firearm related injuries to protect children and improve pediatric outcomes (Lee et al., 2022). Within this model the maximization of individual rights while at the same time minimizing the potential for negative effects to promote positive health outcomes is the goal to strike a balance between personal freedom and the collective goal of safeguarding lives (Beidas et al., 2020). Hence, a harm prevention model for firearm safe storage practices would acknowledge that individual gun ownership is currently a right in the U.S. Determining a balance to preserve personal liberties and address the overarching and mutual goals of protecting and preventing deaths in children should be a goal within this model. Conceptualizing a working model for harm reduction to address firearm safety practices requires empirical evidence from all stakeholders in this issue to identify and refine each of the elements proposed clearly. From this work, best practices, principles, and pillars may be identified to help guide education and actions related to future firearm safety efforts (Mueller et al., 2023; Substance Abuse and Mental Health & Services Administration (SAMHSA), 2023). A public health approach may be helpful if integrated with examples of primary, secondary, and tertiary harm reduction efforts. The four main characteristics of the public health approach include: 1. Definition of the problem, 2. Identification of Risk Factors and protective factors, 3. Development, testing, implementation, and evaluation of Prevention Strategies and interventions, and 4. Scaling effective interventions to facilitate widespread adoption of prevention strategies (Mueller et al., 2023). A working concept (Figure 1) outlines key questions to identify with key stakeholders to specifically address the factors associated with safe firearm storage practices and is a starting point for future inquiry and coalition building. A harm reduction model defined within this approach would identify the evidence-based principles, pillars, and best practices to achieve a prevention strategy to achieve firearm safe storage practices and outcomes to reduce pediatric morbidity and mortality. Integrating the concepts related to these phenomena is described with a set of questions that may guide future investigations and engage stakeholders, beginning with nurses to define the main components of the harm reduction model for firearm safety. Education focused on nurses' knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs related to firearm safe storage practices and the risks of poor storage may be an initial step of actions to address safety behaviors until a more comprehensive, evidence-based model is developed.

Figure 1. Key Questions for a Working Harm Reduction Model for Firearm Safety

Strategies for Nurses to Reduce or Prevent Firearm Violence

Nurses comprise the largest group of healthcare professionals in the country. This majority holds an untapped potential to influence firearm violence prevention strategies. Focused efforts should advocate for policy changes at the macro level and engage in structured grassroots conversations with students, patients, families, and communities to drive individual-level change (Cogan, 2023). Gun violence is a pressing public health crisis affecting individuals and communities across the United States, with firearm-related injuries now being the leading cause of death among children and adolescents (Goldstick et al., 2022). A survey by the Pew Research Center revealed a 50% increase in gun-related deaths among children and teenagers between 2019 and 2021 (Gramlich, 2023), reaching the highest numbers in at least two decades (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, n.d.).

Effectively addressing the crisis of unintentional firearm deaths among children requires a multifaceted advocacy approach that considers the complex social, economic, and political factors contributing to gun violence. Trusted and highly educated healthcare professionals like nurses have a crucial role to play in promoting gun safety and injury prevention through evidence-based policies that protect public health (Cogan, 2023). Holistic practices that mitigate harm and foster safety integrate interventions such as anticipatory guidance, lethal means counseling, community interventions, and advocacy, (Lee et al., 2022). Lethal means counseling refers to suicide prevention, assessing if someone is at risk for suicide and has access to a gun, a recognized term in gun violence prevention through public health lens (Lee et al., 2022). Nurses have a pivotal role as advocates who can empower families with evidence-based knowledge to make informed decisions regarding their behaviors to improve safety within the household, particularly if they are firearm owners. At all points of care, from primary care visits to school nurses appointments, nurses may find opportunities to navigate the delicate dialogues to discuss the adoption of safe practices such as proper storage, unloading, and separation from ammunition, thereby fostering a culture of safety to reduce the risk of unintentional firearm injuries and fatalities (Combe & Cogan, 2023).

Frontline nurses witness the devastating consequences of gun violence in many clinical settings.Frontline nurses witness the devastating consequences of gun violence in many clinical settings. Working in emergency departments, trauma centers, and critical care units, they are often the first to respond to patients with gunshot wounds and their families. Nurses provide life-saving care, manage complex injuries, and support patients and families throughout recovery. Beyond the bedside, nurses possess a unique perspective on the root causes of gun violence, including social determinants of health, mental health, and access to healthcare, education, and employment opportunities. Leveraging their exceptional communication skills and deep knowledge, nurses in these settings can develop partnerships that may help lead firearm injury prevention education initiatives and promote health equity within communities where violence occurs (Cogan, 2023).

The importance of patient education and counseling for firearm violence prevention is an important tool within a prevention strategy. Numerous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of healthcare providers' counseling and interventions in reducing firearm injuries and deaths (Rowhani-Rahbar et al., 2016; Webster & Kopp, 2018). Nurses may use clinical encounters to discuss gun safety with patients and their families, covering safe storage practices, identifying unintentional injury risk factors, and recognizing signs of suicide risk. Collaboration with community organizations, law enforcement, and stakeholders to develop tailored gun safety programs addressing specific patient needs, including safe firearm storage, domestic violence risks, and reporting suspicious behavior (Fowler et al., 2017).

Ultimately, grass-roots, clinically focused, firearm-safe storage measures must be reinforced with policy development. There is a need for nurses to leverage their influence as trusted healthcare professionals, collective expertise, and voices to advocate for evidence-based policies, such as universal background checks, known to reduce firearm homicides and suicides at all levels of their communities, and at the highest levels of government (Santaella-Tenorio et al., 2016). Nurses must be educated and empowered to partner with state and federal legislators, journalists, and scholars to use the available data to develop the appropriate strategies to operationalize safe storage legislation. Critical in this dialogue is a discussion of supportive policies to limit firearm access for high-risk individuals, including domestic abusers, and those with diagnosed mental and behavioral illnesses (Swanson et al., 2015).

...nurses are well-equipped to identify and address the underlying factors contributing to gun violence...As frontline healthcare providers, nurses are well-equipped to identify and address the underlying factors contributing to gun violence, including poverty, racism, discrimination, and barriers to healthcare and education. Collaboration with community organizations and policymakers to develop comprehensive strategies that enhance access to healthcare and social services, promote economic, and educational opportunities (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2023). A systematic review by Rowhani-Rahbar and colleagues (2016) highlights the positive impact of physician counseling and training on firearm safety (Rowhani-Rahbar et al., 2016). Similarly, nursing interventions can significantly impact patient outcomes by promoting firearm safety and gun violence prevention. Nurses, trained in emergency trauma care and community-based education, play a vital role in preventing injury and death from gun violence (Choma, 2023; Cogan et al., 2019). School nurses, for example, are the initial point of contact for students, and have a unique opportunity to identify and address firearm-related risks by being at a daily point of contact between students and their families (Combe & Cogan, 2023). In addition to implementing education strategies to reinforce students, families, and school staff on safe storage practices, dangers of firearms at home, and advocate for evidence-based policies, such as safe storage laws and youth-focused firearm laws (Webster & Kopp, 2018).

Nursing leaders, including those in academic settings, can provide education and training to nursing students and professionals on identifying and responding to firearm-related injuries. They can advocate for policy changes at organizational and governmental levels, including universal background checks and red flag laws, to reduce firearm-related injuries and deaths (Santaella-Tenorio et al., 2016). Nurses possess unique insights and expertise to make a significant impact on reducing gun-related injuries and deaths. Through education, advocacy, and evidence-based interventions, nurses can contribute to a culture of safety and wellness that values human life. Gun violence is a complex public health crisis that demands a multifaceted approach, with nurses playing a pivotal role in driving meaningful change.

Nurses have yet to enact their collective voice to inform gun safety efforts fully. At a fundamental level nurses need to be knowledgeable about the issues and the history of policy. Nurses partnered with communities, students, families, schools, and law enforcement agencies could develop comprehensive programs to protect communities. More importantly, nurses encounter the devastating consequences of gun violence firsthand in their clinical practice when it is often too late and where efforts offer too little to keep patients safe. Nurses in emergency departments, trauma centers, and critical care units provide life-saving interventions, manage complex wounds, and support patients and families throughout recovery. Nurses have a unique perspective on the root causes of gun violence and can link both the clinical influences of mental health and the social determinants of health.

Table 1. Nursing Actions Using a Harm Reduction Model to Prevent Firearm Injury

|

Goal |

Reason |

Nursing Action |

|---|---|---|

|

Reduce Firearm Injuries |

To minimize the immediate harm and long-term consequences of firearm injuries. |

1. Provide education about safe firearm storage practices, including providing gun locks. Education with equipment are most effective. 2. Offer resources and support for those at risk of firearm-related harm. 3. Collaborate with community organizations to host gun safety workshops. Health fairs, for example, can include opportunities for attendees to learn more about safe firearm storage. |

|

Prevent Suicides by Firearm |

To reduce the risk of suicides involving firearms, as they are often impulsive and lethal. |

1. Screen patients for suicide risk and facilitate access to mental health resources. 2. Educate patients and families about recognizing signs of suicide risk. 3. Advocate for safe storage practices and initiating Extreme Risk Protection Orders for high-risk individuals. |

|

Advocate for Policy Change |

To address the structural factors contributing to firearm injuries. |

1. Lobby for evidence-based policies, including universal background checks and Extreme Risk Protection Orders. 2. Collaborate with advocacy groups to promote gun safety legislation. 3. Educate policymakers on the public health impact of gun violence. |

|

Promote Community Safety |

Address social determinants of firearm injuries in communities. |

1. Collaborate with organizations to address factors like poverty and discrimination. 2. Support initiatives for healthcare, education, and economic access. 3. Advocate for community development programs to reduce violence. |

Conclusion

Nurses have a vital role in firearm violence prevention, as they are often the first point of contact for patients at risk for firearm violence. Nurses can make a significant difference in preventing firearm violence in their communities by assessing risk factors, providing education, advocating for policy change, and referring patients to resources. However, nurses face challenges and barriers, including a lack of training and education, fear of offending patients, and limited resources for mental health support. It is essential to address these challenges to enable nurses to play a more effective role in firearm violence prevention.

Authors

Sunny G. Hallowell PhD, APRN, PPCNP-BC

Email: sunny.hallowell@villanova.edu

ORCID ID: 0000-0003-1862-2505

Sunny G. Hallowell, PhD, APRN, PPCNP-BC believes health care should be patient-centered, evidence-based, supported by policy and open to innovation. Nationally recognized as a Josiah Macy Foundation Faculty Scholar she belongs to a forward-thinking group of nurses and physicians poised to lead health care in the country. She is currently an Associate Professor at the M. Louise Fitzpatrick College of Nursing at Villanova University she is known for her innovative approach to education and research that integrates her skills in health services research, health policy, pediatrics, and health care innovation. Dr. Hallowell views American healthcare through a lens that is deeply rooted in her experiences growing up within diverse ethnic cultures and national health systems and brings to her teaching and research over 20 years of clinical experience in pediatrics.

Robin Cogan, MEd, RN, NCSN, FNASN, FAAN

Email: robin.cogan@rutgers.edu

ORCID ID: 0000-0003-3919-807X

Robin Cogan, MEd, RN, NCSN, FNASN, FAAN is a nationally recognized school nurse with over two decades of experience in the Camden City School District. She represents New Jersey on the Board of Directors of the National Association of School Nurses. Robin is the Clinical Coordinator and part-time lecturer for the School Nurse Specialty Program at Rutgers-Camden School of Nursing. Her influential work in school nursing has garnered numerous awards and recognition, and she has been featured as a case study in the National Academies of Medicine Future of Nursing 2030 report. Robin has written extensively about the public health crisis of gun violence and advocates on behalf of student and staff safety in schools.

References

AFFIRM at The Aspen Institute. (n.d.). Affirm our impact. AFFIRM at The Aspen Institute. https://affirmresearch.org/impact

American Academy of Pediatrics. (n.d.). Extreme risk protection orders (ERPO) or “red flag” laws. https://www.aap.org/en/advocacy/state-advocacy/extreme-risk-protection-orders-erpo-or-red-flag-laws/

Beidas, R. S., Rivara, F., & Rowhani-Rahbar, A. (2020). Safe firearm storage: A call for research informed by firearm stakeholders. Pediatrics, 146(5), e20200716. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-0716

Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. (2023). Firearms—guides—importation & verification of firearms, ammunition—gun control act definitions—firearm. https://www.atf.gov/firearms/firearms-guides-importation-verification-firearms-ammunition-gun-control-act-definitions

Canadian Pediatric Society. (2008). Harm reduction: An approach to reducing risky health behaviors in adolescents. Paediatrics & Child Health, 13(1), 53–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/13.1.53

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). CDC WONDER. https://wonder.cdc.gov/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, August 28). Fatal injury and violence data | WISQARS | Injury center | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/fatal/index.html

Choma, E. G. (2023). A community educational intervention to improve firearm safety behaviors in families. Journal of Pediatric Health Care: Official Publication of National Association of Pediatric Nurse Associates & Practitioners, 37(4), 364–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2023.01.001

Cogan, R. (2023). Nurses and gun violence prevention: Protecting the public’s health. Nursing Economic$, 41(3). http://www.nursingeconomics.net/necfiles/2023/MJ23/109.pdf

Cogan, R., Nickitas, D. M., Mazyck, D., & Hallowell, S. G. (2019). School nurses share their voices, trauma, and solutions by sounding the alarm on gun violence. Current Trauma Reports. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40719-019-00179-1

Combe, L. G., & Cogan, R. (2023). School nurses can reduce firearm injuries and deaths. NASN School Nurse, 38(4), 205–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/1942602X231174190

Davis, A., Kim, R., & Crifasi, C. K. (2023). A year in review: 2021 gun deaths in the U.S. Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. https://publichealth.jhu.edu/sites/default/files/2023-06/2023-june-cgvs-u-s-gun-violence-in-2021.pdf

Everytown Research & Policy. (2023). Minimum age to purchase. Everytown Research & Policy. https://everytownresearch.org/rankings/law/minimum-age-to-purchase/

Ford, C. A., Mirman, J. H., García-España, J. F., Fisher Thiel, M. C., Friedrich, E., Salek, E. C., & Jaccard, J. (2019). Effect of primary care parent-targeted interventions on parent-adolescent communication about sexual behavior and alcohol use: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Network Open, 2(8), e199535. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.9535

Fowler, K. A., Dahlberg, L. L., Haileyesus, T., Gutierrez, C., & Bacon, S. (2017). Childhood firearm injuries in the United States. Pediatrics, 140(1), e20163486. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-3486

Goldstick, J. E., Cunningham, R. M., & Carter, P. M. (2022). Current causes of death in children and adolescents in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine, 386(20), 1955–1956. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2201761

Gramlich, J. (2023). Gun deaths among U.S. children and teens rose 50% in two years. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/04/06/gun-deaths-among-us-kids-rose-50-percent-in-two-years/

Hawk, M., Coulter, R. W. S., Egan, J. E., Fisk, S., Reuel Friedman, M., Tula, M., & Kinsky, S. (2017). Harm reduction principles for healthcare settings. Harm Reduction Journal, 14(1), 70. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-017-0196-4

Lee, L. K., Fleegler, E. W., Goyal, M. K., Doh, K. F., Laraque-Arena, D., Hoffman, B. D., & The Council On Injury, Violence, And Poison Prevention. (2022). Firearm-related injuries and deaths in children and youth. Pediatrics, 150(6), e2022060071. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2022-060071

Library of Congress. (2023). U.S. Constitution—Second Amendment. Constitution Annotated. https://constitution.congress.gov/constitution/amendment-2/

Mueller, K. L., Lovelady, N. N., & Ranney, M. L. (2023). Firearm injuries and death: A United States epidemic with public health solutions. PLOS Global Public Health, 3(5), e0001913. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001913

NRA Explore. (n.d.). NRA Firearm Training. https://firearmtraining.nra.org/

Office of Governor Gavin Newsom. (2023, September 15). California becomes first state in America to call for constitutional convention on right to safety. https://www.gov.ca.gov/2023/09/15/california-becomes-first-state-in-america-to-call-for-constitutional-convention-on-right-to-safety/

Parkes, T., Matheson, C., Carver, H., Foster, R., Budd, J., Liddell, D., Wallace, J., Pauly, B., Fotopoulou, M., Burley, A., Anderson, I., Price, T., Schofield, J., & MacLennan, G. (2022). Assessing the feasibility, acceptability and accessibility of a peer-delivered intervention to reduce harm and improve the well-being of people who experience homelessness with problem substance use: The SHARPS study. Harm Reduction Journal, 19(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-021-00582-5

Ramchand, R. (2022). Personal firearm storage in the United States. https://www.rand.org/research/gun-policy/analysis/essays/personal-firearm-storage.html

Rostron, A. (2018). The Dickey amendment on federal funding for research on gun violence: A legal dissection. American Journal of Public Health, 108(7), 865–867. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304450

Rowhani-Rahbar, A., Simonetti, J. A., & Rivara, F. P. (2016). Effectiveness of interventions to promote safe firearm storage. Epidemiologic Reviews, 38(1), 111–124. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxv006

Saad, L. (2020). U.S. Ethics ratings rise for medical workers and teachers. Gallup. https://news.gallup.com/poll/328136/ethics-ratings-rise-medical-workers-teachers.aspx

Sandy Hook Promise. (n.d.). Safe storage. Sandy Hook Promise Action Fund. https://actionfund.sandyhookpromise.org/issues/gun-safety/safe-storage/

Santaella-Tenorio, J., Cerdá, M., Villaveces, A., & Galea, S. (2016). What do we know about the association between firearm legislation and firearm-related injuries? Epidemiologic Reviews, 38(1), 140–157. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxv012

Substance Abuse and Mental Health & Services Administration. (2023). Harm reduction framework. https://www.samhsa.gov/find-help/harm-reduction/framework

Swanson, J. W., McGinty, E. E., Fazel, S., & Mays, V. M. (2015). Mental illness and reduction of gun violence and suicide: Bringing epidemiologic research to policy. Annals of Epidemiology, 25(5), 366–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.03.004

UC Davis Health News. (n.d.). What are ‘red flag’ laws and how can they prevent gun violence? News. https://health.ucdavis.edu/news/headlines/what-are-red-flag-laws-and-how-can-they-prevent-gun-violence/2023/01

Watts, T., Bane, C., Brandley, J., Schmidt, E., & Tucker, M. (2023). Nursing harm reduction education and care for people who use drugs or who engage in sex work. Public Health Nursing, 40(5), 762–765. https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.13230

Webster, W., & Kopp, R. (2018). Using virtual reality for community outreach and student recruitment. Engineering Design Graphics Journal, 82(2), 70–75. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1211934