The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis (TSUS) was a 40-year study based in Macon County, Alabama. Miss Eunice Rivers, RN, a public health nurse and scientific assistant, was a critical, long-term worker in the TSUS. After scandal closed the TSUS in 1972, Rivers was the target of adverse attention, often portrayed as the only woman involved in the study in both fictional depictions and other nonfiction sources. No other women were identified as culpable. A review of the TSUS publications revealed the contributions of other women in the TSUS. Publications and other historical sources identified these women, their active roles, and even accolades bestowed. This article reviews the myth of Eunice Rivers as the lone woman involved in this study. The discussion offers analysis of the women in these roles and their subsequent publications. Eunice Rivers co-authored two TSUS publications. Six white women co-authored 11 publications. In conclusion, pre-1972, the public health research experiences of Rivers and the white women appeared equitable in their public exposure. Post 1972 TSUS disclosure in the media, equity vanished, and Rivers was the sole target of adverse attention. All women who had roles in the TSUS matter. This article addresses an unmet need for equitable full disclosure and reckoning.

Key Words: Eunice Rivers, public health nurse, Tuskegee Study, myths, Lida Usilton

The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis (TSUS) was a 1932–1972 study in rural Alabama. The study followed two groups of black men to autopsy. The groups were approximately 400 men with syphilis found untreated and then a comparable group of approximately 200 presumably non-syphilitic men (Peters et al., 1955; Schuman et al., 1955). The study intentionally excluded women because of the risk of congenital syphilis (Shafer et al., 1954a; 1954b).

The study ended in scandal in 1972 after a nation-wide, Associated Press news story.

The TSUS was a collaboration between the United States Public Health Service (USPHS), and the Alabama State and Macon County public health departments. Tuskegee Institute, the John A. Andrew Memorial Hospital (JAAMH), and the Tuskegee Veterans Administration Hospital (TVAH)–black-run institutions–locally coordinated the study. The Milbank Memorial Fund, a New York City philanthropy, supported study-related autopsies and burial expenses. Tuskegee Institute received and disbursed the funds (Vonderlehr et al., 1936; Peters et al., 1955). The study ended in scandal in 1972 after a nation-wide, Associated Press news story (Heller, 1972).

Rivers has been falsely assumed to be the only woman with a role in the study.

Miss Eunice Rivers, the black public health nurse, who then was the scientific assistant with the Division of Venereal Disease of the USPHS, drew public ire. Regarding her role in the TSUS, she was depicted as an example of wrongdoing and ethical lapses in nursing and research (Spiers et al., 2012). Rivers has been falsely assumed to be the only woman with a role in the study (Hammonds, 1994).

Prior to 1972, the public health and research experiences of Rivers and the white women appeared equitable in their public attention.

This article addresses one myth about the TSUS, that Eunice Rivers was the “only female officially involved in the study” (Hammonds, 1994, p. 324). A review of TSUS publications identified other women, their roles in the TSUS, and perhaps, accolades bestowed. Prior to 1972, the public health and research experiences of Rivers and the white women appeared equitable in their public attention. Post-1972 TSUS exposure in the media, equity vanished, and Rivers was the target of negative characterizations, i.e., “…she was either a middle-class race traitor or a powerless nurse” (Reverby, 2009, p.168). This article provides more complete and accurate information on Rivers and other white women involved in the TSUS and its context.

Eunice Rivers: The Only Woman

Post TSUS media disclosure in 1972, Miss Eunice Rivers, a black public health nurse assigned to the study, became the “only face” of the TSUS and an unfair target of relentless negative characterizations (Jones, 1993; Gray, 1998; Reverby, 2000; Reverby, 2009). The 2005 Radcliffe Quarterly exemplified this (Drexler, 2003, p. 17):

“...Nurse Rivers endures as the project's symbol of both treachery and victimhood—even more than the government doctors who masterminded the experiment. ‘There's something wrong about focusing only on a black woman in this story,’ she says. ‘Why is everybody so fixated by her? Partly it's a kind of nurse-mommy thing. We know doctors can be mean and awful, but we want mommy the nurse to fix everything. Partly, it's a throwback to a mammy view of black women [italics added]. And because she's the only visible woman [italics added] in the whole study, we want her to behave differently.’”

The “she” quoted above was the editor and author of Tuskegee’s Truths and Examining Tuskegee, respectively (Reverby, 2000; Reverby, 2009).

Miss Eunice Rivers...became the “only face” of the TSUS and an unfair target of relentless negative characterizations.

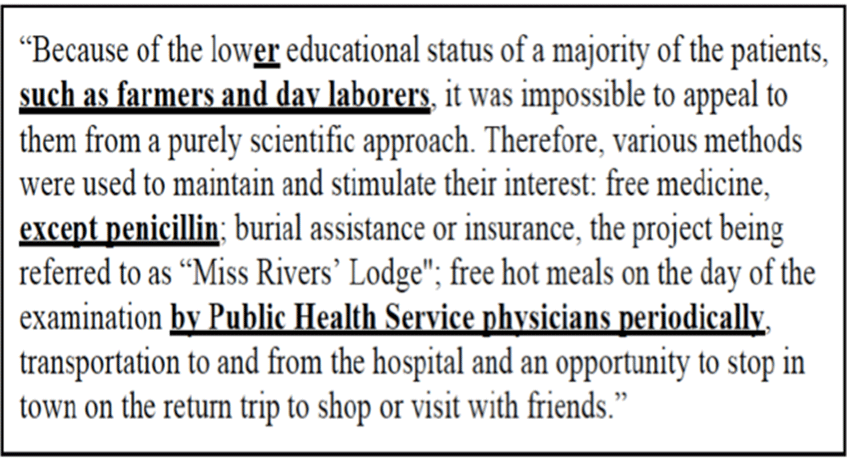

An important paragraph from Rivers’ first-authored article provided an example of the myths that seeped into the TSUS dialogue (Rivers et al., 1953). The paragraph (see Figure) had four inserts added to it in testimony presented at the 1973 Senator Edward Kennedy committee hearings on human experimentation. The insertions were: (a) -er added to low, (b) such as farmers and day laborers, (c) except penicillin, and (d) by Public Health Service physicians, periodically (Figure). Senator Kennedy heard the altered paragraph spoken at his 1973 hearings (Gray, 1973, p.1034). Later, two books included the altered paragraph (Gray, 1995, p. 283-284; Gray, 1998, p. 58). All three documents falsely attributed the altered paragraph to Rivers’ article (Rivers et al., 1953).

Figure. Paragraph from Rivers’ First-Authored Article with Insertions

Note: Origin of Tuskegee Study and Eunice Rivers discord from Testimony from Quality of Health Care—Human Experimentation hearings, March 8, 1973 (Gray, 1973, p. 1034). Senator Edward Kennedy heard this testimony. Insertions into quote from Miss Eunice Rivers’ article (Rivers et al., 1953, p. 393) are indicated by: underscore and bold. (Courtesy of the Journal of the National Medical Association) (White, 2019).

Nevertheless, after identification of the four insertions, this re-imagined paragraph is a valuable tool to decipher the message imparted by the created myths and untruths. The meanings or intentions of the inserts introduced elements of: (a) and (b) classism (and perhaps racism); (c) denial of penicillin; and (d) government maleficence (with the non-inclusion of black doctors) (White, 2019). But that tainted paragraph in the Figure never existed in Rivers’ article (Rivers et al., 1953).

Bad Blood was the first TSUS full-length book (Jones, 1993). The author later reminisced, “Nurse Rivers…is the only person to whom I devoted an entire chapter” (Jones, 2011, p. 25). There were no equal descriptions of other women involved with the TSUS in Bad Blood.

Fictional Depictions

The performing arts entertained and educated students and professionals with the play, Miss Evers’ Boys and later the Home Box Office (HBO) movie, an adaptation of the play with the same title (Sargent, 1997; Feldshuh, 1995a; Palmer, 1997). Both were fictional accounts of a true event, the TSUS, but the artistic license in the productions seemingly is misrepresented in ethics teaching as a true account (Palmer, 1997; Butts, 2007; Spiers et al., 2012). The play and movie focused on the public health nurse involved with the study. In one of the play scenes, the lead character, Miss Eunice Evers, pulled out of line one of the TSUS characters at the Birmingham Rapid Treatment Center (RTC). This was before the character received “a hip shot of that penicillin” (Feldshuh, 1995a, p. 69-71). Although fictional, the glaring denial of treatment on stage was disturbing. Audiences might have believed that the man was one penicillin shot away from treatment and/or cure. Note that Birmingham was at least 100 miles from Tuskegee, blurring the true account of the scene.

The play and movie focused on the public health nurse involved with the study.

The 1997 HBO movie, Miss Evers’ Boys (Sargent, 1997), fixed the 100-mile logistic problem by transforming the denial of treatment scene to a hospital clinic in the county that neighbored Macon County. In the movie, a white nurse blocked the penicillin shot based on the character’s name being on a TSUS list, and then declared, “Tuskegee Study! No penicillin allowed.” And outside the clinic, Evers rushed up, caught, and explained to the man the potential dangers of that shot (Pain666kill1, 1997a). The play and movie differed on “the true account” of what happened at penicillin denial. Both were supposed portrayals of Evers’ professional behavior.

None of these fabricated “clinics” existed in the early 1940s to early 1950s.

RTCs were, nevertheless, intense, in-patient facilities, requiring a graduate nurse for hands-on patient care to administer intramuscular penicillin every 2- or 3-hours--day and night--for approximately two weeks or 70+ penicillin shots (Heller & Eslick, 1946). The Birmingham RTC was markedly different than the fictional clinics in Miss Evers’ Boys (the play and movie), and clinic depictions in Bad Blood ("the rapid-schedule treatment clinics") (Jones, 1993, p. 162); Nursing History Review (“a penicillin treatment center in Birmingham” or "a clinic in Birmingham") (Reverby, 1999, p. 16, 27); Tuskegee’s Truths (“U.S. Public Health Service Rapid Treatment Penicillin Clinic, ca. late 1940s”) (Reverby, 2000, p. 185); an “Originally published in Science” reprint (“…using penicillin in several of its clinics”) (Fairchild & Bayer, 2000, p. 590); and Medical Apartheid (“PHS's ‘fast track’ VD-treatment clinics”) (Washington, 2006, p. 165). None of these fabricated “clinics” existed in the early 1940s to early 1950s. And pre-1950s, it was not the alleged denial of “a hip shot of that penicillin” and “a penicillin shot,” respectively, as performed in Miss Evers’ Boys, both play and movie.

There was a personal affront, however, in the 1997 HBO movie, Miss Evers’ Boys (Sargent, 1997). At the inception of the TSUS in 1932, it was the Depression. The doctor in charge of the Tuskegee Hospital laid-off Evers based on a “staff or medicine” argument. Evers had seniority for a hospital ward position, but she refused to replace another nurse. Later the fictional Evers testified at the Senate hearings (Rivers did not testify at Senator Kennedy’s 1973 Senate hearings), “…six months passed with no word….I had to take a job… the only one I could find…working as a domestic, just like my mother….” (quoted from the film) (Sargent, 1997). In the next scene in the HBO movie, Evers had exchanged her public health nurse uniform for a domestic uniform. Then she served white women lemonade while they played bridge. The women were oblivious to Evers. There was no dialogue (Pain666kill1, 1997b). The apparent humiliation of Evers, in this scene, spoke volumes.

In the next scene in the HBO movie, Evers had exchanged her public health nurse uniform for a domestic uniform.

Although the domestic scene in the HBO movie was not in the play, there were lines about Evers’ domestic work. The dialogue between one of the characters with syphilis and Miss Evers concerned what work she did since working for the county and when “the really bad times hit in ’30.” Evers responded, “Domestic work when I could get it” (Feldshuh, 1995b, p. 27). The dialogue in the play seemed benign. The domestic–tea party scene in the HBO movie visually seemed to degrade Evers (Sargent, 1997).

Additional Non-Fiction Sources

According to her first-authored article, Eunice Rivers worked for eight years for the Alabama State Department of Health. She came back to the JAAMH to work as a night supervisor. “In 1932, Miss Rivers was offered a position as night supervisor in a New York general hospital. She chose, instead, to stay in Alabama as a scientific assistant with the Division of Venereal Disease of the Public Health Service” (Rivers et al., 1953, p. 393). During the Depression, Eunice Rivers had employment and choices in her chosen field of nursing. There was no evidence that Rivers or her mother worked as a domestic. Rivers’ mother worked on the farm (Thompson, 1979).

There was no evidence that Rivers or her mother worked as a domestic.

Tuskegee’s Truths, a 600-page edited volume about the TSUS, had a section devoted to Rivers, “Rethinking the Role of Nurse Rivers.” The section reprinted oral history, two previously published articles, and two segments from previously published books (Reverby, 2000). No one else involved with the TSUS had this much attention.

No one else involved with the TSUS had this much attention.

In 2009, an interesting example of Rivers portrayal appeared in Examining Tuskegee (Reverby, 2009), the most recent TSUS standard narrative. An archival photograph showed Rivers measuring the height and weight of a TSUS participant. A USPHS doctor, wearing protective goggles in preparation for fluoroscopy on the men, was in attendance. He was recording the data. The photo was taken in the pristine, black-run TVAH in 1952. Superimposed over this photograph was another photograph of a room from the long-closed JAAMH, which was in poor repair and dilapidated (Drexler, 2003, p.17). The composite, in reality, did not exist.

The re-imagined photo of research space in a black-run facility might have compounded the negative sentiment toward Rivers.

The re-imagined photo of research space in a black-run facility might have compounded the negative sentiment toward Rivers. The comment in Examining Tuskegee (Reverby, 2009) was “Rivers, as she raises her arm to get the scale lever, looks as if she is performing a lynching [italics added] that is watched by a masked white man as the walls are falling down. As the story of the Study took on cultural meaning in the next decades, both images of Rivers—of her doing her work and of her work literally using death to control black men—would become iconic” (p. 184). And yes, visitors to Tuskegee University queried, “why the men were examined in such deplorable conditions” (Reverby, 2009, p. 318[n. #105]).

When did black women lynch black men, as was depicted by and attributed to Rivers in the photo? Eunice Rivers had primary and secondary knowledge of racial violence. First, as a child, she remembered that “…the Ku Klux Klan came and got my daddy and took him out and beat him” (Thompson, 1979, p. 4). Another time her father was falsely accused of aiding and abetting a black murder suspect, who killed a white police officer. At night, white men shot into the family home. These horrific experiences caused her “to have a peculiar feeling toward the white man.” Because her work in public health brought her “…in close contact with the white people…,” Rivers “…decided differently, that they all were not bad” (Thompson, 1979, p. 21). Second, in another ironic example, Tuskegee Institute kept the records of all racial lynching in the United States (Moton, 1933; Williams, 1970). Third, even more important, Rivers was very close to or “attached to… the Work family” (Thompson, 1979, p. 8-9). Mr. Work influenced her life at Tuskegee. She stated that Mr. Work was “just like my daddy” (Thompson, 1979, p. 19). Monroe Work was the director of the Institute’s Department of Records and Research, which collected the lynching records nation-wide (Work, 1937). The statement in Examining Tuskegee about Rivers, “… as if she is performing a lynching…,” (Reverby, 2009, p. 184) was both ahistorical and nonsensical.

Another example of the negative characterization of Eunice Rivers was in the form of a survey of TSUS scary beliefs.

Another example of the negative characterization of Eunice Rivers was in the form of a survey of TSUS scary beliefs (Davis et al., 2012). One survey query focused on Rivers. The query was, “The nurse who recruited them [TSUS men] was Black” (Davis et al., 2012, p. 60). Of course, the answer was “True.” But the “scary answer” was also “True”! There was no rationale or documentation for why the public health nurse in the TSUS being black was scary, particularly, in contrast to a white nurse in segregationist Alabama. This “scary answer” appeared counterintuitive. In the survey, however, over 85% of blacks and whites answered the scary belief query, “The nurse who recruited them was Black,” wrongly as “False” (Davis et al., 2012, p. 60). The survey participants may have had information or insight about other women’s involvement in the TSUS. This may have been lacking in the researchers, who designed the queries and designated post hoc what answer was “scary.”

Last, two narratives limited and narrowed the involvement of professional women in the TSUS to Eunice Rivers. One stated that Rivers was the “only female officially involved in the study” (Hammonds, 1994, p. 324). In another article, the researchers explained the limits in a white woman’s knowledge about the TSUS in their survey was because “white females did not play a major role” in the TSUS and they “were not made totally aware of what went on with the experiment” (Green et al, 1997, p. 199). There was no rationale or documentation for these explanations.

The above sample was a part of what became “fact” and/or part of the relentless negative characterization of Eunice Rivers.

Other Women in the TSUS

...the 15 known TSUS publications contradicted the myth that there were no other women...

Review of the 15 known TSUS publications contradicted the myth that there were no other women—who knew about and were involved with the TSUS; simply look at the co-authors.The table offers a sample of publications that described other women involved with the TSUS and their roles.

Table. Examples of Publications Describing Women Involved with the Tuskegee Study

|

Date, Journal |

Name, Degree |

Role or Position |

|

1946, Venereal Disease Information |

Martha C. Bruyere |

statistical analysis |

|

1950, American Journal of Syphilis, Gonorrhea, and Venereal Diseases 1954a, Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly 1954b, Public Health Reportsa 1955, Journal of Chronic Diseases |

Geraldine A. Gleeson, AB |

health program analyst

statistician

statistician |

|

1953, Public Health Reports 1955, Journal of Chronic Diseases |

Eunice A. Rivers, RN |

public health nurse

scientific assistant |

|

1954a, Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly 1954b, Public Health Reportsa |

Lida J. Usilton, ScD |

public health administrator |

|

1955, Journal of Chronic Diseases 1956b, J Chron Dis |

Dorothy Rambo, RN |

statistician |

|

1956a, AMA Archives of Dermatology 1973, Journal of Chronic Diseases |

Eleanor V. Price |

statistician former assistant chief, clinical research |

|

1964, Archives of Internal Medicine |

Anne Roof Yobs, MD |

chief, medical research, Venereal Disease Research Laboratory |

a This was the same manuscript as the one in the Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly.

Eunice Rivers was not the first woman whose name was within one of the TSUS articles.

Eunice Rivers was not the first woman whose name was within one of the TSUS articles. Lida Usilton and Martha Buyere, both statisticians, appeared in an unnumbered footnote on the bottom of the first page in two 1946 articles (Deibert & Bruyere, 1946; Heller & Bruyere, 1946). Buyere also co-authored one of these articles and was the first woman TSUS co-author (Deibert & Bruyere, 1946). Public Health Reports advertised the availability of reprints of these articles for the public in the section, “Public Health Service Publications: A List of Publications Issued During the Period…,” for a nominal charge of 10 and 5 cents, respectively (USPHS, 1947a; 1947b). Rivers’ name was not in either article, even in the footnote with the other 11 members of the TSUS team. The text of one of the 1946 articles mentioned, “…a nurse in the local health department has kept in constant touch with the members of the group” (Heller & Bruyere, 1946, p. 34).

Geraldine Gleeson, a health program analyst and statistician, co-authored four publications (Pesare, et al., 1950; Peters, et al., 1955; Shafer, et al., 1954a; 1954b).One of these publications (the autopsy article) credited Rivers for “devotion to the study and to the welfare of this group of patients over the twenty years has been in large part responsible for the opportunity to secure cooperation of the patient and family in permitting post-mortem study” (Peters et al., 1955, p. 128). This post-mortem work with a female co-author was “Presented at the Second World Congress of Cardiology and the 27th Annual Scientific Session of the American Heart Association” (p. 127) in 1954.

In 1953, Eunice Rivers, a public health nurse, was the only female first-author on any of the known TSUS articles.

In 1953, Eunice Rivers, a public health nurse, was the only female first-author on any of the known TSUS articles. Rivers was a 1922 graduate of the Tuskegee Institute School of Nursing. Her first-authored article was the first to label the study with “Tuskegee,” i.e., “Tuskegee untreated syphilis study” (Rivers et al., 1953, p. 393). It is important to note that Rivers was an executive of the Tuskegee Alumni, which pledged $2,000 to $3,000 to Tuskegee Institute’s financially ailing Nurse Training School to save it from closure. The source of this information recognized Rivers as “Special Research Assistant U. S. Public Health Service” (Kenney, 1939).

Lida Usilton, a public health administrator, and Gleeson co-authored two publications (Shafer, et al., 1954a; 1954b). The publications were the same manuscript, but in two different journals, i.e., the journal of the funding philanthropy and a public health journal. This was the publication that revealed that the study was limited to males to avoid the risk of transmission of congenital syphilis. It was also the publication that provided the public with critical statistics on costs of uncontrolled syphilis in VD Fact Sheet (U. S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1954), annually, for nearly 20 years. Information from this TSUS publication and its citation, with full names of the female co-authors (e.g., Usilton, Lida J.; Gleeson, Geraldine A.), appeared in VD Fact Sheet (U. S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1971) until the 1972 TSUS disclosures in the media (Heller, 1972).

Interestingly, the publications associated with Lida Usilton showed that her academic degree progressed from a master’s degree as seen in footnotes in the two 1946 TSUS articles to a ScD doctoral degree in her two 1954 publications (Deibert & Bruyere, 1946; Heller & Bruyere, 1946; Shafer, et al., 1954a; 1954b). Recently, during the COVID-19 pandemic, The New York Times reflected on Usilton (Murphy, 2020). In the 1940s to 1950s, syphilis tracking/holding contributed to the national venereal disease control program, which decimated early syphilis rates in the United States. The Times referred to Usilton as the “boss of the operation” and a “poker-playing biostatistician” (para. 10). The recent Times article did not connect Usilton to the TSUS even though the study was a part of the national venereal disease control program.

The recent Times article did not connect Usilton to the TSUS ...

Eleanor Price, a statistician and a former assistant chief, co-authored articles in 1956 and 1973, respectively (Caldwell et al., 1973; Olansky et al., 1956a). In 1969, Price served as a resource person at a CDC meeting with an outside expert committee to discuss closure of the TSUS (U. S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1973).

Two registered nurses (RNs) co-authored an article in 1955. The nurses were Rivers, a scientific assistant, and Dorothy Rambo, a statistician (Schuman et al., 1955). Their article included a table listing patients who received adequate penicillin treatment in the late 1940s to early 1950s. Rambo co-authored another article in 1956 (Olansky et al., 1956b). As RNs, this was important because the American Journal of Nursing (AJN) acknowledged their authorships. The AJN featured both articles in the section, “Nurse Authors in Current Periodical Literature.” (Wright, 1956a; 1956b).

Anne Roof Yobs, MD, chief of medical research, Venereal Disease Research Laboratory, co-authored the 1964 30-year anniversary article (Rockwell et al., 1964). This article had two tables, listing patients, who received adequate therapy and penicillin.

The American Journal of Public Health (AJPH) provided a platform for review of TSUS preliminary research results and a final publication. Women co-authored the articles, which were the subject of AJPH reviews. First, 20-year preliminary data from the future 1954 life expectancy (Shafer et al., 1954a; 1954b) and the 1955 autopsy (Peters et al. 1955) articles were presented at the 1953 Annual Meeting of the American Public Health Association and then summarized in an article (Shafer, 1954). Second, the 1964 30-year anniversary article was reviewed in “A Selected Public Health Bibliography with Annotations” (Potthoff, 1965). Subsequently, in a letter-to-the-editor, the USPHS chief of the venereal disease branch took exception to a comment in the review about the performance of the specific treponemal serological test. He further reminded the reviewer that the emphasis in the TSUS article was “…to review the status of the study group and report clinical findings” (Brown, 1965, p. 810) and not the new syphilis serological test. The editor of AJPH clarified the reviewer’s comment (Brown, 1965). Thus, the work of Usilton, Gleeson, and Yobs had additional broad exposure in the public health community.

Several major conclusions about the articles co-authored by women are:

- Eunice Rivers co-authored two TSUS publications.

- Six white women co-authored 11 TSUS publications.

- Except for Dr. Yobs (Rockwell, et al., 1964), all of the other white women were statisticians (see Table) who collated the data and then calculated life expectancies and morbidity and mortality rates for syphilitic versus presumably non-syphilitic comparisons and TSUS publications.

White women, thus, were co-authors who: (a) were “officially involved in the study;” (b) were “totally aware of what went on with the experiment;” and (c) did “play a major role” in the TSUS (Hammonds, 1994, p. 324; Green et al., 1997, p. 199). This section has briefly clarified the existence and extent of a sample of other women’s roles in the TSUS.

Discussion

Authorships of TSUS articles seemed to be an easy means to an end to identify other women involved with the TSUS.

Authorships of TSUS articles seemed to be an easy means to an end to identify other women involved with the TSUS. In Bad Blood’s section, “A Note on Sources,” there was a list of all the known TSUS publications. For all the articles, Bad Blood listed the authors as “1st-author et al” (e.g., J.K. Shafer et al.). Except for Rivers, who was a first author, the book obscured all of the other women’s names with the use of “et al” (Jones, 1993). Also, only the names of Rivers and Yobs appeared in the book’s “Name Index.”

Dr. Yobs dismissed an inquiry from a reader, complaining about the 1964 30-year anniversary article, which she co-authored. The inquirer suggested that the USPHS and the co-authors “need to reevaluate their moral judgments in this regard” (in reference to the “untreated” contents of the 1964 30-year anniversary article) (Jones, 1993, p. 190). There was an indication in Bad Blood that linked Yobs to the article. But Bad Blood referred to her as “Anne Q. Yobs" (Jones, 1993, p. 190). Her name on the 1964 30-year anniversary article was “Anne Roof Yobs” (Rockwell et al., 1964).

Tuskegee’s Truths and a 1997 Research Nurse article duplicated the “1st-author et al” designation for TSUS authors in “Published Reports on the Study” section (e.g., Shafer, J.K., et al.) (Reverby, 2000, p. 606-607) and in a box (e.g., Shafer JK et al.) (Reverby, 1997, p. 5), respectively. The box in Research Nurse seemingly was an ideal platform to disclose the full names of the other female co-authors because journal restrictions and limitations may not have applied to an exhibit.

Examining Tuskegee posted, in “Published Primary Sources,” the TSUS articles as 1st-author full name plus co-author initials + last name or et al (Reverby, 2009), except for one of the 1954 life expectancy publications (Shafer et al., 1954b), which had full disclosure of all the names, including the two female co-authors. The book did include the full names of the six other women who co-authored in Notes in the back of the book (Reverby, 2009, p. 314 [n. #5]). In general, with the other author names obscured in “et al” or first initials, unearthing and revealing the full names on TSUS articles appeared appropriate for this article.

The negative characterizations of Eunice Rivers were progressive...from isolation to distortion, fabrication, and omission.

The negative characterizations of Eunice Rivers were progressive, as described above, from isolation to distortion, fabrication, and omission. This appeared unusual for someone previously lauded and rewarded for her work with the TSUS men. It might be perceived that Rivers was an easy target to negatively characterize and express what seemed to be latent disparagements about a black woman. In the outrage and mistrust surrounding the TSUS, who cared or dared to do anything about it, publicly or otherwise?

In 1958, the Washington Post might not have seen Rivers as “scary” (Davis et al., 2012) when the Post reported her receipt of the Distinguished Service Award and “the coveted Oveta Culp Hobby Award” from the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) (Lawson, 1958). The article reported HEW’s description of Rivers, rendering “notable service…selfless devotion, and skillful human relations” (Lawson, 1958). The article continued with “She has been the keystone in a monumental study (italics added) of venereal disease control in Eastern Alabama’s Macon County…” (p. B3). The study described was the TSUS because the Post continued with, “The program, begun in 1932, had as its aim to maintain detailed case studies of 600 Negro farm workers, 400 of whom had active syphilis [italics added]” (p. B3). The majority (Lawson, 1958) and minority (“Double Citation for U.S. Nurse”, 1958; “Report of Eunice Rivers Laurie HEW award”, 1958) print media and public health (“Eunice Rivers Laurie”, 1958) and nursing (“Oveta Culp Hobby Award goes to USPHS nurse”, 1958) articles reported these “scary” accolades about Rivers. There was no outrage.

Four years earlier, however, Lida Usilton received the William Freeman Snow Award for Distinguished Service to Humanity from the American Social Hygiene Association (“Woman, pioneer in V.D. control wins Hygiene Association Award”, 1954). One of the many reasons for the award began in 1943-1944. Usilton collaborated with the states to develop mass blood-testing programs to “administer penicillin to the largest number of infected persons possible within a limited period of time” (Mather, 1954, p. 166). She assisted in the launch of the rapid treatment centers program, which was a critical component “to insure that treatment for syphilis would be completed during hospitalization” (Mather, 1954, p. 166).

The rapid treatment centers were in-patient facilities and nurses were necessary for the program to work, particularly, administration of intramuscular shots of penicillin frequently to complete treatment in under two weeks (Heller & Eslick, 1946). Also, Usilton received an honorary Doctor of Science degree (ScD) from Smith College in 1953 (Marquis Who's Who Inc, 1963; Smith College Archives, 1953). The citation about her read as, “...a pioneer in the application of biostatistics, she has made notable contributions to progress in the field of public health” ("Award of Honorary Degrees", Citations, 1953, p. 201). Furthermore, her accolades continued with, “Recognized as one of the outstanding women in the field of medicine and public health, she has protected the health and lives of hundreds of thousands of women and children” (Smith College Archives, 1953). The ScD degree was after her name on the two 1954 TSUS publications that she co-authored (Shafer, et al., 1954a; 1954b).

In 1997, the government apology for the TSUS by President William Jefferson Clinton omitted both Eunice Rivers and the other women.

There may have been some semblance of equity, in one example, between the black public health nurse and the white women. The above recognitions and accolades of these women were before the 1972 TSUS disclosures (Heller, 1972). In 1997, the government apology for the TSUS by President William Jefferson Clinton omitted both Eunice Rivers and the other women. President Clinton apologized to: (a) survivors of the syphilis study at Tuskegee, (b) hundreds of other men, (c) wives and children, (d) community of Macon County, (e) City of Tuskegee, (f) Tuskegee University, (g) the larger African American community, and (f) the doctors who have been wrongly associated with the events there (The White House Office of the Press Secretary, 1997). Again, there was no apology for Rivers or the white women involved with the study.

The assumption that no other women knew or were involved with the TSUS was unjust to Eunice Rivers...

With regard to Rivers, if the lack of a presidential apology was not enough, the lack of an appropriate rationale was particularly egregious. The plaintiffs’ lead attorney for the TSUS lawsuit versus the USA, when asked why he did not include Rivers and Tuskegee Institute as defendants, offered a rationale (Gray, 1998). The attorney, in brief, believed that “Rivers was misled, betrayed, and was also a victim of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study” (Gray, 1998, p. 86). The attorney offered an analogous argument for Tuskegee Institute, i.e., he “felt the same about Tuskegee Institute as…about Nurse Rivers–that the Institute and its officials were misled, betrayed, and taken advantage of as she had been” (p. 86). The attorney concluded with, “So the President, in his apology to surviving Study participants…recognized that Tuskegee Institute, along with these participants and the whole community were lied to and betrayed by the federal government” (p.87).Thus, Tuskegee Institute (now University) received a presidential apology, but not Rivers. Despite the Institute and Rivers sharing the same rationale for exclusion as lawsuit defendants, this same rationale did not include Rivers in the apology (Gray, 1998).

Conclusion

The assumption that no other women knew or were involved with the TSUS was unjust to Eunice Rivers, the public health nurse/scientific assistant. The assertion of non-involvement of other women in the study did not match co-authorships of TSUS articles. The Justice section of the Belmont Report suggested a model for this inequity, i.e., “the Tuskegee syphilis study used disadvantaged, rural black men to study the untreated course of a disease that is by no means confined to that population” (National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, 1979, p. 9). The media, books, articles, and performance arts/entertainment identified and negatively characterized the black nurse when TSUS involvement was not confined to her. The pathological view, regarding Rivers, spanned from the only woman in the TSUS to her work “lynching” black men. White women were deeply involved but not identified and negatively characterized post 1972 TSUS disclosure.

Only identifying the black public health nurse, when there were white women involved, is inequitable, and thus a race issue. Only identifying the nurse, when there were statistical, administrative, and medical personnel involved, is inequitable, i. e., a class issue. In sum, all women who had roles in the TSUS should be revealed, because they matter.

Author

Robert M. White, MD, FACP

Email: rmwhite@wesleyan.edu

ORCID ID: 0000-0003-0269-7553

Robert M. White, MD, FACP, is a medical oncologist in Silver Spring, MD. After earning a BA (with honors in chemistry) from Wesleyan University, he earned an MD at New Jersey Medical School in Newark, NJ. His training included an internship at New Jersey Medical School, an internal medicine residency and oncology fellowship at Georgetown University Medical Center, and a clinical associateship in basic and clinical research at the National Institutes of Health. Dr. White’s professional experiences included an academic position as an associate professor of Medicine at the Howard University Cancer Center in Washington, DC. He last served as a medical officer who reviewed new cancer drugs for safety and efficacy in the Division of Oncology Drug Products at the US Food and Drug Administration. Dr. White is now conducting a re-analysis of the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis (TSUS) given his expertise in clinical medicine, medical research, and black medical history. His medical school textbook of medicine, Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine (1974), introduced him to the TSUS. He has published peer-reviewed articles and letters-to-the-editor on the TSUS. His research and writings reframe the TSUS and offer a pre-1972-based paradigm that challenges the prevailing historical narrative.

References

Award of Honorary Degrees, Citations. (1953). Smith Alumnae Quarterly, 44(4), 201. https://saqonline.smith.edu/publication/?m=45764&i=431252&p=11&pp=1&ver=html5

Brown, W. J. (1965). Letter to the editor. American Journal of Public Health, 55(6), 809-810. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.55.6.809

Butts, H. M. (2007). Miss Evers' Boys. Journal of the National Medical Association, 99(2), 175–176. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2569435/

Caldwell, J. G., Price, E. V., Schroeter, A. L., & Fletcher, G. F. (1973). Aortic regurgitation in the Tuskegee study of untreated syphilis. Journal of Chronic Diseases, 26(3), 187-194. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(73)90089-1

Davis, J. L., Green, B., & Katz, R. V. (2012). Influence of scary beliefs about the Tuskegee Syphilis Study on willingness to participate in research. Association of Black Nursing Faculty Journal, 23(3), 59–62. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22924230/

Deibert, A. V., & Bruyere, M. C. (1946). Untreated syphilis in the male Negro III. Evidence of cardiovascular abnormalities and other forms of morbidity. Journal of Venereal Disease Information, 27(12), 301-314. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=inu.30000100134133&view=1up&seq=339&skin=2021.

Double Citation for U.S. Nurse. (1958). The Chicago Defender, May 10, 3.

Drexler, M. (2003). Testifying on Tuskegee. Radcliffe Quarterly, Winter. https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:427992528$15i.

Eunice Rivers Laurie. (1958). Personals: Eunice Laurie. American Journal of Public Health, 48(8), 1113. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1551735/pdf/amjphnation01078-0145.pdf.

Fairchild, A. L. & Bayer, R. (2000). The uses and abuses of Tuskegee. In: Reverby, S. M. (Ed.), Tuskegee’s Truths: Rethinking the Tuskegee Syphilis Study (1st ed.) (pp. 589-603). University of North Carolina Press. http://ftp.columbia.edu/itc/hs/pubhealth/p9740/readings/fairchild-bayer.pdf

Feldshuh, D. (1995a). Scene 2. Act 2, 1946, Birmingham rapid treatment center. Miss Evers’ Boys. New York: Dramatists Play Service, Inc, 69-71.

Feldshuh, D. (1995b). Scene 1, Act 1, 1932. Inside the Possom Hollow Schoolhouse, Early evening. Miss Evers’ Boys (domestic discussion). New York: Dramatists Play Service, Inc, 27.

Gray, F. (1973). United States. Quality of health care–human experimentation, 1973: Hearings before the Subcommittee on Health on labor and public Welfare, United States Senate, ninety-third Congress, first session, on S. 974 ... U.S. Government Print Office. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=umn.31951p00622678q&view=1up&seq=252&skin=2021

Gray, F. D. (1995). Bus ride to justice. Changing the system by the system. The life and works of Fred D. Gray. The Black Belt Press.

Gray, F. D. (1998). The Tuskegee Syphilis Study. The Real Story and Beyond. River City Publications.

Green, B. L., Maisiak, R., Wang, M. Q., Britt, B. F., & Ebeling, N. (1997). Participation in health education, health promotion and health research by African Americans: Effects of the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment. Journal of Health Education, 28(4), 196-201. https://doi.org/10.1080/10556699.1997.10603270

Hammonds, E. M. (1994). Your silence will not protect you. Nurse Rivers and the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. In: White E. C. (Ed.) The black women’s health book. Speaking for ourselves. (pp. 323-331). Seal Press.

Heller, J. (1972, July 26). Syphilis victims in U.S. study went untreated for 40 years. New York Times, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1972/07/26/80798097.pdf?pdf_redirect=true&ip=0).

Heller, J. R., & Bruyere, P. T. (1946). Untreated syphilis in the male Negro II. Mortality during 12 years of observation. Journal of Venereal Disease Information, 27(2), 34-38. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=inu.30000100134133&view=1up&seq=48&skin=2021.

Heller, J. R., & Eslick, M. (1946). The rapid treatment center program. American Journal of Nursing, 46(8), 542-544. https://doi.org/10.2307/3457376

Jones, J. H. (1993). Bad Blood: The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment (revised ed.). Free Press.

Jones, J. H. (2011). Chapter 2: Of thanks and forgiveness. In Katz , R. V., & Warren, R. C. (Eds.) The search for the legacy of the USPHS Syphilis Study at Tuskegee. Lexington Books.

Kenney, J. A. (1939). SOS. Save the clinic! [editorial]. Journal of the National Medical Association, 31(3), 117-118. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2624339/pdf/jnma00745-0033.pdf.

Lawson, J. (1958, April 19). Negro nurse honored: Tuskegee public health aide wins U. S. Welfare award. Washington Post.

Marquis Who’s Who Incorporated. (1963). Lida Josephine Usilton, In Who’s Who of American Women (3rd ed.). A. N. Marquis Company.

Mather, P. R. (1954). To Lida J. Usilton…. Journal of Social Hygiene, 40(5), 164-168. http://reader.library.cornell.edu/docviewer/digital?id=hearth4732756_886_005#page/6/mode/1up.

Moton, R. R. (1933, December 31). Crime and disaster. The New York Times. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1933/12/31/100815354.pdf?pdf_redirect=true&ip=0.

Murphy, K. (2020, May 23). Contact tracing is harder than it sounds. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/23/sunday-review/coronavirus-contact-tracing.html?searchResultPosition=1A.

The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. (1979). The Belmont report: Ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research. Regulations, Policy & Guidance. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.31822024336521&view=1up&seq=27&skin=2021

Olansky, S., Harris, A., Cutler, J. C., & Price, E. V. (1956a). Untreated syphilis in the male Negro. Twenty-two years of serologic observation in a selected syphilis study group. AMA Archives of Dermatology, 73(5), 516-522. https://doi.org/10.1001/archderm.1956.01550050094017

Olansky, S., Schuman, S. H., Peters, J. J., Smith, C. A., & Rambo, D. S. (1956b). Untreated syphilis in the male Negro. X. Twenty years of clinical observation of untreated syphilitic and presumably nonsyphilitic groups. Journal of Chronic Disease, 4(2), 177-185. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(56)90019-4

Oveta Culp Hobby Award goes to USPHS nurse. (1958). New highlights: Oveta Culp Hobby Award goes to USPHS nurse. American Journal of Nursing, 58(6), 786. https://journals.lww.com/ajnonline/toc/1958/06000

Pain666kill1. (1997a). Miss Evers’ Boys 1997 TV Eng spa [Video]. YouTube. 1:22:53 (denial of penicillin shot scene). https://youtu.be/jhhZo1Vi_J4?t=4973.

Pain666kill1. (1997b). Miss Evers’ Boys [Video]. YouTube, 43:54 (domestic scene). https://youtu.be/jhhZo1Vi_J4?t=2635.

Palmer, L. I. (1997). Paying for suffering: The problem of human experimentation. Maryland Law Review, 56, 604-623. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs/533

Pesare, P. J., Bauer, T. J., & Gleeson, G. A. (1950). Untreated syphilis in the male Negro: Observation of abnormalities over 16 years. American Journal of Syphilis, Gonorrhea, & Venereal Disease, 34(3), 201-213. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15410959/

Peters, J. J., Peers, J. H., Olansky, S., Cutler, J. C., & Gleeson, G. A. (1955). Untreated syphilis in the male Negro. Pathologic findings in syphilitic and nonsyphilitic patients. Journal of Chronic Diseases, 1(2), 127-148. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(55)90204-6

Potthoff, C. J. (1965). Thirty year follow-up on syphilis. American Journal of Public Health, 55(3), 484. https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/pdf/10.2105/AJPH.55.3.483

Report of Eunice Rivers Laurie HEW award. (1958). Cleveland Call and Post, May 10, 1-D.

Reverby, S. M. (1997). History of an apology: From Tuskegee to the White House. Research Nurse, 3(4), 1-9. http://academics.wellesley.edu/WomenSt/ResearchNurse.pdf

Reverby, S. M. (1999). Rethinking the Tuskegee syphilis study. Nurse Rivers, silence and the meaning of treatment. Nursing History Review, 7, 3-28. http://www.columbia.edu/itc/history/rothman/COL479E4442.pdf

Reverby, S. M. (Ed.). (2000). Tuskegee’s Truths: Rethinking the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. University of North Carolina Press.

Reverby, S. M. (2009). Examining Tuskegee: The Infamous Syphilis Study and its Legacy. University of North Carolina Press.

Rivers, E., Schuman, S. H., Simpson, L., & Olansky, S. (1953). Twenty years of follow-up experience in a long-range medical study. Public Health Report, 68(4), 391-395. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2024012/pdf/pubhealthreporig00184-0037.pdf.

Rockwell, D. H., Yobs, A. R., & Moore, M. B. (1964). The Tuskegee study of untreated syphilis: The 30th year of observation. Archives of Internal Medicine,114, 792-798. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1964.03860120104011

Sargent, J. (Director). (1997). Miss Evers’ Boys [Film]. HBO Home Video.

Schuman, S. H., Olansky, S., Rivers, E., Smith, C. A., & Rambo, D. S. (1955). Untreated syphilis in the male Negro. Background and current status of patients in the Tuskegee study. Journal of Chronic Disease, 2(5), 543-558. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(55)90153-3

Shafer, J. K. (1954). Applied epidemiology in venereal disease control. American Journal of Public Health, 44(3), 355-359. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1620540/pdf/amjphnation00356-0062.pdf

Shafer, J. K., Usilton, L. J., & Gleeson, G. A. (1954a). Untreated syphilis in the male Negro—A prospective study of the effect on life expectancy. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly, 32(3), 263-273.

Shafer, J. K., Usilton, L. J., & Gleeson, G. A. (1954b). Untreated syphilis in the male Negro—A prospective study of the effect on life expectancy. Public Health Rep, 69(7), 684-690. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2024307/pdf/pubhealthreporig00175-0078.pdf

Smith College Archives. (1953). Usilton, Lida Josephine – ScD, 1953. Honorary Degree Files. https://findingaids.smith.edu/repositories/4/archival_objects/28693.

Spiers, J. A., Paul, P., Jennings, D., & Weaver, K. (2012). Strategies for engaging undergraduate nursing students in reading and using qualitative research. The Qualitative Report, 17(24),1-22. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2012.1762

Thompson, A. L. (1979). Interview with Eunice Laurie, October 10, 1977. In Black Women Oral History Project. Radcliffe College. https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:45173970$1i

U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare: Public Health Service Communicable Disease Center. (1954). Costs of uncontrolled syphilis. In VD fact sheet, 11, 4-5. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=osu.32435054341623&view=1up&seq=6&skin=2021.

U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare: Public Health Service. Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (1971). Costs of uncontrolled syphilis (p. 3). In VD fact sheet 1971: Basic statistics on the venereal disease problem in the United States (28th ed). https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=chi.34036476&view=1up&seq=41&skin=2021.

U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare-Public Health Service. (1973). Final report of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study ad hoc Advisory Panel. U.S. Public Health Service. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiug.30112056575225&view=1up&seq=17&skin=2021.

United States Public Health Service (USPHS). (1947a). Reprints for The Journal of Venereal Disease Information, #256. Public Health Report, 62(4), 135. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.b2949160&view=1up&seq=177&skin=2021.

United States Public Health Service (USPHS). (1947b). Reprints for The Journal of Venereal Disease Information, #275. Public Health Report, 62(28),1026. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015008106521&view=1up&seq=98&skin=2021.

Vonderlehr, R. A., Clark, T., Wenger, O. C., & Heller, J. R. (1936). Untreated syphilis in the male Negro. A comparative study of treated and untreated cases. Journal of the American Medical Association, 107, 856-86. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1936.02770370020006

Washington, H. A. (2006). Chapter 7: A notoriously syphilis soaked race: What really happened at Tuskegee? In: Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present. Doubleday.

White, R. M. (2019). Driving Miss Evers’ Boys to the historical Tuskegee study of untreated syphilis. Journal of the National Medical Association, 111(4), 371-382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnma.2019.01.002

The White House. Office of the Press Secretary Clinton, W.J. (1997, May 16). Remarks by the President in apology for study done in Tuskegee. Clinton White House Archives. https://clintonwhitehouse4.archives.gov/textonly/New/Remarks/Fri/19970516-898.html.

Williams, D. T. (1970). Eight Negro Bibliographies. Kraus Reprint Company.

“Woman, pioneer in V.D. control wins Hygiene Association Award.” (1954, April 27). Woman, pioneer in V.D. control wins Hygiene Association Award. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1954/04/27/archives/woman-pioneer-in-v-d-control-wins-hygiene-association-award.html

Work, M. N. (1937). Division IX. The Negro and lynching. In: Negro Year Book. An Annual Encyclopedia of the Negro, 1937-1938. Tuskegee, Negro Year Book Publishing Company.

Wright, M. J. (1956a). Nurse Authors in Current Periodical Literature. American Journal of Nursing, 56(1), 28.

Wright, M. J. (1956b). Nurse Authors in Current Periodical Literature. American Journal of Nursing, 56(10), 1332.