Media influences us through the propagation of ideas, including stereotypes that can affect career choice, a crucial issue due to the global shortage of nurses and midwives. While content creators behind and in front of the camera typically have told stories that stereotype nurses, two current shows break the pattern. Our approach to the analysis focuses on midwife characters portrayed in the BBC’s Call the Midwife and Claire Temple, RN, of the Marvel cinematic universe (Netflix). Building on themes identified as problematic by film scholar Kathleen McHugh related to female nurse depictions (gender, care, drama), our analysis expands to include who the character is, why she does what she does, and how nurse characters provide care by engaging with her clinical work, colleagues, and patients. In our discussion, we show how these media makers got it right by resisting the stereotypic extremes in order to portray more nuanced, complex characters in meaningful contexts, resulting in more interesting and compelling stories. We conclude by offering steps for taking action to impact the image of nurses and nursing.

Key Words: Image of nurse, gender stereotypes, sexual identity, nurse portrayals, media portrayals of nurses, stereotypes (social psychology) in mass media, mass media and nurses, nurses on television, Call the Midwife, Claire Temple, Night Nurse, Luke Cage

Stories are a powerful means of communication. Stories are a powerful means of communication. When told through television shows, films, webisodes, and video games, stories speak to an expansive audience, helping to shape our culture, our perceptions of norms, and the way we understand the world around us (Turow, 2012). In March 2018, we were panelists at a parallel event for the United Nations (UN) - Commission on the Status of Women in New York. Our panel of eight speakers was titled, “Women/Girls in Media: Power, Storytelling, and #MeToo.” It was co-sponsored by various non-governmental organizations, including Pathways to Peace (2018), an official Peace Messenger of the UN that has Consultative Status with the UN Economic and Social Council. We spoke to a standing-room only crowd including delegates and representatives from various countries. The purpose of our presentation was to address the influence of media on gender equality and the dynamics that dictate which stories get told and by whom. In particular, we focused on the cost to society when women (1st author) and nurses (2nd author) are portrayed in stereotypical, inaccurate, or distasteful ways.

It is not uncommon for media to conflate women and nurses, creating added problems of representation. It is not uncommon for media to conflate women and nurses, creating added problems of representation (Kalisch & Kalisch, 1987; McHugh, 2012). This can have crucial implications for nurses not only in terms of visibility but also voice (Buresh & Gordon, 2006; McHugh, 2012; Summers & Summers, 2015). In a recent study on nursing and news media, Mason and colleagues (2018) found that journalists in their sample perceived nurses to have lower status in society since most are women; therefore, they rarely consult nurses as sources for health news. Failure to recognize the value of professional nursing regardless of the gender of the nurse is harmful to the profession, including misrepresentation or lack of representation of nurses in media. This phenomenon makes it harder for Registered Nurses (RNs) to be understood by the public or policy makers. It may complicate the path toward greater funding for development of the profession and more health system decisions that support nursing in its mission to provide safe, effective, clinical care (Buresh & Gordon, 2006; Heilemann, Brown, & Deutchman, 2012; Summers & Summers, 2015).

The World Health Organization (WHO) has projected a global shortage of nine million nurses and midwives by 2030 (WHO, 2018). Gender inequity and a poor image of nursing in many countries complicates this worldwide problem (Wilson & Fowler, 2012). The United States (U.S.) has been called upon to create policy and build a workforce without pulling clinicians from less resourced countries that have dire needs for nurses as well (O’Brien & Gostin, 2011). An added difficulty is that qualified nurses do not want to work under the available conditions for nurses in many countries (Buchan & Aiken, 2008; Oulton, 2006). Factors that deter applicants from choosing to become a nurse or to remain actively employed as a nurse warrant continued analysis and action.

Depictions in media have the potential for influencing career choice, which has implications for nursing. Depictions in media have the potential for influencing career choice, which has implications for nursing. For example, viewers of the CBS show Ally McBeal (1997-2002) tended to have more positive views of the legal profession (Kitie, 1999). Research shows that girls who watched Dana Scully on the X Files (1993-2002 on Fox) reported that they were influenced to become scientists (21st Century Fox, 2018). While it is possible that positive nurse characters on TV may have a similar effect, studies have shown that teens and young adults who otherwise might have been interested in a nursing career were negatively influenced by media depictions of the work done by nurses in hospital dramas (Glerean, Hupli, Talman, & Haavisto, 2017; Weaver, Salamonson, Koch, & Jackson, 2013).

Nursing has been perceived by U.S. college students as a “women’s occupation” that lacks independence and therefore is less desirable (Seago, Spetz, Alvarado, Keane, & Grumbach, 2006). Historically, when it comes to portrayals of nurses on television and in film, stereotypic and subservient caricatures, stripped of nuance, have plagued nurse depictions for decades (Kalisch & Kalisch, 1987; Summers & Summers, 2015). A related problem has been the complete absence of nurse characters in the cast of some medical dramas altogether (Gordon, 2006; Heilemann, 2012; Kalisch, Begeny, & Neuman, 2007; Summers & Summers, 2015; Turow, 2012).

...some producers and writers have succeeded in creating high-quality, mainstream shows that center female nurse characters who defy the old stereotypes...A step in the right direction is the creation of compelling stories that accurately showcase the professional, autonomous work of nurses inside and outside the hospital. This is indeed possible. In fact, some producers and writers have succeeded in creating high-quality, mainstream shows that center female nurse characters who defy the old stereotypes, amass a strong fan base, and garner critical acclaim. In this article, we have used criteria from film scholar Kathleen McHugh (2012) to focus on two current, popular franchises that portray nurses in groundbreaking ways to explore and analyze what makes these portrayals so successful. We conducted a close reading of the shows in the tradition of literary analysis, discussing the implications for nursing and future needs for action. Our first example is Claire Temple, a nurse character in the Marvel cinematic universe on Netflix. Played by Rosario Dawson, the character of Claire was originally inspired by a 1970s comic book series called “Night Nurse” and she comes to life on screen today in a fictitious world in the 21st century (Kelly, 2018). The second is the cast of Call the Midwife (CTM) a serial drama now in its eighth season on the BBC and popular in United States on PBS and Netflix (Brockes, 2013). See the Table for a brief plot summary to provide context.

Table. Plot Summaries

|

Claire Temple, RN in the Marvel Universe on Netflix |

Call the Midwife on the BBC Featuring Various Midwife Characters |

|

Claire Temple is a nurse character on various shows in the Marvel cinematic universe on Netflix. The character was originally inspired by a 1970s comic book series, “Night Nurse,” and she comes to life on screen in a fictitious version of “Harlem” in the 21st century. |

An ensemble cast of midwives and nuns work in the tenements and working class neighborhoods in the East End of London during the 1950s-1960s. Housing was crowded and poverty was high. The plot of each episode features at least one birth. |

With Claire Temple, Marvel fans see a nurse often taking center stage as she contends with everyday human beings as well as superheroes, anti-heroes, and criminals. She has had storylines in various shows in the Marvel universe since 2015, including Jessica Jones, Luke Cage, Iron Fist, and The Defenders (Internet Movie Database, 2018). She has been called a breakthrough character and inspired critics and fans to ask that she be given her own show (Kelly, 2018; Paige, 2015). In addition, Claire Temple is a woman of color, a rarity on screen.

According the Center of the Study of Women in Television and Film (Lauzen, 2018), women made up just 40% of speaking roles on television, and of those roles only 33% were women of color. This phenomenon prevails even though 50.8% of the population in America are women, and of them, 41.5% are women-of-color (United States Census Bureau, 2017). Claire has the potential to be a role model whose trajectory pushes past the historical disenfranchisement that the nursing profession has propagated against women of color (Barbee, 1993).

CTM is based on the personal memoirs of Jennifer Worth, a nurse who went on to become a midwife and work in east London during the 1950s. Thus, CTM is a period piece that puts women and nursing in the center of its dramatic stories. In fact, the show was built with the goal of making midwives visible (Thomas, 2012). Taking place in the impoverished tenements and working class neighborhoods of London’s East End during the 1950s-1960s, every episode revolves around the heroism of giving birth and helping women give birth. This women-only activity is portrayed as beautiful, important, and brave. Through the episodes, we gain insight into the post World War II lived realities of women at a time when demolished housing had not been rebuilt, so life in the crowded tenements was hard.

This focus on women is not just in front of the camera. CTM made headlines when only women were selected to direct its third season, an unusual occurrence in a profession that is 85% male (Silverstein, 2013). Hiring women directors is particularly significant because doing so is correlated with having more women both in front of and behind the camera (Lauzen, 2018).

The shows are similar in that they both address social justice issues seriously, if imperfectly.While both shows have urban settings, the location and time period of our two examples are quite different. That of Claire Temple is a fictitious 21st century “Harlem,” while the nurse midwives live in mid-20th century London. The shows are similar in that they both address social justice issues seriously, if imperfectly. This compels the viewer to ponder with the characters the dilemmas they face, providing a potent avenue for character development worthy of closer scrutiny (Baugher, 2018; Nussbaum, 2016).

Our Approach to Analyzing the Depictions of Nurse Characters

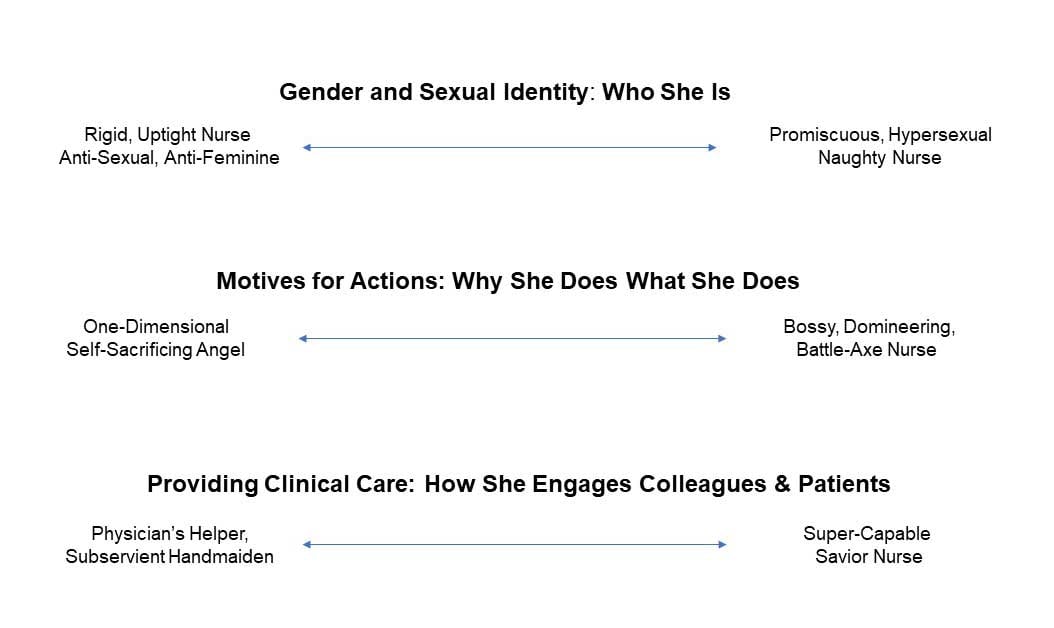

To analyze the depictions of these nurse characters, we drew from and expanded upon McHugh’s (2012) articulation of three challenging issues (gender, care, and drama) that confront scriptwriters, directors, and producers when developing female nurse characters. The first of McHugh’s three issues involves the ways in which the gender and sexuality of the nurse character is portrayed; we see this as including the identity of the nurse overall or who the nurse is. The second issue involves the kind of care that nurse characters provide; however, we extend McHugh’s second issue to include not only the kind of work that the nurse is depicted as doing, but also her motivation or why she does what she does in her life and her work. McHugh’s third issue is about drama: the compelling nature (or lack thereof) of how nurses execute the care they provide on screen. We deepen conceptualization of the third issue to involve not only the dramatic portrayal of the nurse but how she interacts with people around her including personal friends, other health providers, administrators, and patients, and how they respond to her. If the context and nuance of these three aspects are misunderstood or given insufficient consideration, the writers can slide down a slippery slope to stereotyping.

It is so much easier to rely on a troupe then to create rich, complex nurse characters. It is so much easier to rely on a troupe then to create rich, complex nurse characters. While doing a simple Google search at the time of the writing of this article, using the search terms, “avoiding stereotypes of women in writing,” results included over 20 million websites on the topic (see examples: “How to Avoid,” n.d.; Jepsen, 2018; Thomas, 2013). The development of these resources indicates the enormous size of the problem of writing women stereotypically and the interest in resisting that tendency.

This framework helps organize our close reading of the ways Claire Temple, RN, of the Marvel Cinematic Universe and the nurse midwife characters of mid-century London bend and break stereotypes. We propose that each of these issues (i.e. the who, the why, the how) can be conceptualized on a continuum with the more stereotypical depictions representing nurse “types” on the distant ends of the continuum (See Figure). We suggest that Claire Temple and the midwife characters are successful because they fall in the middle of these continua, resulting in more nuanced, more interesting characters and stories.

Figure.

Issue 1: Gender and Sexual Identity of Nurse Depictions: Who She Is

...the gender and sexual identity of nurse characters has often been misrepresented and stereotyped in media. As McHugh (2012) pointed out, the gender and sexual identity of nurse characters has often been misrepresented and stereotyped in media. While women characters could portray a continuum of gender and sexual identities, nurse characters are typically pegged at the extreme end points. At one extreme, the rigid, uptight nurse is portrayed as sexually unavailable or incapable of having sexual or romantic interest in anyone (Schulman, 2018). This caricature may be hostile towards men, such as Nurse Ratched from the 1975 film, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, who was described as anti-feminine and anti-sexual by feminist critics (Horst, 1977).

Even Jackie Peyton, RN, the lead character of Nurse Jackie on Showtime, was willing to provide sexual favors... At the opposite extreme is the promiscuous or hypersexual nurse, a stereotype that may persist in the public imagination because nurses provide clinical care that involves touching bodies (Cabaniss, 2011). Indeed, the image of a “naughty nurse” has provided fodder for everything from Harlequin Romance novels of the 1950s to present day pornographic media (Gordon, 2006; Summers & Summers, 2015); it has inspired a whole host of risqué Halloween costumes. This caricature has been featured in commercials to sell products from chewing gum to olive oil to sneakers; this nurse even has had roles in cartoons such as Disney’s Roger Rabbit and Steven Spielberg’s Animaniacs (Amidi, 2016). Even Jackie Peyton, RN, the lead character of Nurse Jackie on Showtime, was willing to provide sexual favors to a pharmacist as a way to get painkillers for her aching back.

In contrast to these stereotypes, each of the midwife characters of mid-century London in CTM is portrayed as a three-dimensional person with unique characteristics that make them who they are beyond their gender or sexual lives. While much has been rightfully made of how the media reduces women (and particularly women of color) to objects (American Psychological Association, 2007; Lugo, 2015; Stankiewicz & Rosselli, 2008; Szymanski, Moffitt, & Carr, 2011), here we have accurate depictions of midwives whose specialist training gave them the ability to practice independently in homes, with the option of calling upon a physician if needed.

The midwife characters have their own points of views, relationships, and commitments. They are sexual beings but are not hyper-sexualized. The midwife characters have their own points of views, relationships, and commitments. They are sexual beings but are not hyper-sexualized. They enter into romantic relationships, but their sole purpose on the show is not limited to the role of girlfriend, lover, or wife to some other character. For example, CTM features several celibate characters who are both midwives and nuns, but does not valorize or fetishize the vows of celibacy they have taken. We are introduced to more aspects of their lives and personalities than just their sexuality. For example, we see old and young nuns (Sister Monica Joan and Sister Winifred), kind and difficult nuns (Sister Julienne and Sister Evangelina), nuns who are skilled clinicians and nuns who are just learning (Sister Julienne and Sister Winifred). We meet a midwife named Cynthia who becomes Sister Mary Cynthia (Thomas & O'Sullivan, 2014) and we follow “Sister Bernadette,” whose birth-name is Shelagh, as she leaves the religious life to marry and have children (Thomas & Sharrock, 2013; Thomas & Spiro, 2013; Thomas & Moo-Young, 2013; Warner & Spiro, 2013; Williams & Moo-Young, 2013). In both cases, the decision is not judged as right or wrong but rather it is portrayed as personal and difficult. Women in CTM can have sex or not, be in a sexual relationship or not, but either way they are not defined by their sexual motives or relationships with men.

We are introduced to more aspects of their lives and personalities than just their sexuality.In the Marvel Universe, Claire Temple enters into a sexual relationship with superhero Luke Cage (Coker & Liu, 2018; Croal, Coker, & Johnson, 2016) but her role is neither damsel-in-distress nor idealized sex object. Instead, Claire is depicted as having both sexuality and agency. She is a key character in several plot points, such as helping Luke overcome the infamous “Judas bullet” (Horwitch & Surjik, 2016; Taylor & Shankland, 2016). She fights her own battles, literally fighting off the dangerous “Shades” with the help of another woman character, the injured detective, Misty Knight (Taylor & Tillman, 2016). She is not threatened by Luke’s sexual past; she is unphased upon learning of Misty’s and Luke’s one night stand (Taylor & Tillman, 2016). When Luke begins to slip from her influence, refusing her entreaties to control his anger to the point of punching the wall of their apartment, Claire leaves him (Cooper & Green, 2018; Owens & Jobst, 2018).

...her role is neither damsel-in-distress nor idealized sex object. Claire knows about domestic violence from watching her mother’s abusive relationship as a child and makes a clear decision to leave at the first warning sign of abuse. Claire will not be made a punching bag for any man. Her existence does not hinge on his. In fact, Claire’s character exists regardless of her relationship with Luke in the Marvel Universe, appearing in other shows, and thus showing that she is not solely defined by her sexual potential in a relationship with Luke Cage (Internet Movie Database, 2018).

Issue 2: Motivations Behind Nurse Characters’ Actions: Why She Does What She Does

As was common in media propaganda throughout the 20th century, nurse characters often have been pegged as one-dimensional, self-sacrificing angels whose key motivation for being a nurse is “to give” to others without reservation (NINRnews, 2015). The cost to self or family does not matter. While even nurses sometimes propagate this stereotype (Summers & Summers, 2015), it negates substantive reasons why many people choose nursing as a career, such as the satisfaction from having a scientifically challenging job that combines both an analytic and a humanistic approach; the opportunity to work on a team with other health professionals; or receiving well-deserved salary, health, and vacation benefits. Dill and colleagues (2016) found that nurses motivated to become a nurse due to either intrinsic rewards of the job (e.g., enjoyment of performing complex technical or clinical skills) or extrinsic rewards (e.g., salary, benefits) experienced lower rates of burnout and lower turnover compared to nurses motivated by prosocial reasons (e.g., desire to help others). Thus, the sacrificing angel motif fails to provide an accurate portrayal of a healthy nurse today.

When not pigeonholing nurses as benevolent angels at one end of the spectrum, media has often flopped to the opposite extreme to invoke a terrifying nurse caricature, such as the nurses of American Horror Story: Roanoke, or the character Elle Driver impersonating a nurse in Quantin Tarantino’s Kill Bill Volume 1 and Volume 2. Slightly less extreme are nurse characters who are more bossy and domineering than evil, such as Margaret “Hot Lips” Houlihan on M*A*S*H or Gloria Akilitus on Nurse Jackie. The latter caricatures have come to be known as the battle-axe nurse (Cabaniss, 2011; Summers & Summers, 2015). This nurse is compelled to be in control; she is sure her rules ought to be followed by everyone, which can make such a character all the more terrifying to watch (Schulman, 2018).

In contrast, Claire Temple and the midwives of CTM more closely resemble actual human beings whose motives cannot be consistently or exclusively defined as good or bad. Rather, they do what they do because of their knowledge, skills, values, professional ethics, as well as their goal to heal or care for patients. Moreover, they are not solely nurses - we see them outside of their work lives. Thus, the drama of their interpersonal relationships and personal struggles is just as telling as their work as nurses in terms of who they are.

The Claire Temple we come to know in Luke Cage is clear in her identity. She knows who she is, where she comes from, and what matters to her. When she first appears on screen, we see her chase down a mugger to recover her bag, showing her moxy and ability to manage herself in the hard-knock, urban world (Horwitch & Jobst, 2016).

...Claire’s sharp intellect does not disappoint as she reasons, experiments, and improvises in her clinical role.In addition, Claire has a strong, positive relationship with her mother, confiding in her how she has found her calling helping people “with abilities,” referring to the superheroes of the Marvel universe (Horwitch & Jobst, 2016). In this unique context, Claire is able to combine her street smarts with her nursing skills to problem solve, care for, and heal the wounds of these amazing characters in very dangerous environments. Along the way, Claire’s sharp intellect does not disappoint as she reasons, experiments, and improvises in her clinical role. A telling moment is when Claire informs a physician colleague who is impressed with her skill that her “residency” took place on “145th Street… and my fellowship in Hell's Kitchen,” meaning she learned crucial life-saving skills on the streets and as a nurse (Taylor & Shankland, 2016). Claire’s pride in her profession, self-reliance, sense of place, and rootedness in her neighborhood combine to create her complex motivations.

One of the CTM midwives, Lucille Anderson, is an immigrant to England from Jamaica. Lucille defies stereotypes not only as a midwife, but also as a woman and a person of color. She is an immigrant woman who misses home but is also reluctant to forge new bonds with fellow immigrants. We find out that she has sacrificed for her career and still feels those sacrifices keenly (Gibb & Macartney, 2018). She initially balks at the sex education offered to patients by her nursing peers, rejecting the idea that unmarried women should learn about tampons, before eventually changing her point of view on the issue (Ironside & Sullivan, 2018). Here we see her as imperfect, a woman limited by her time but also able to grow.

Lucille experiences racism from her patients’ family members and members of her church and is unsure how to react (Gibb & Macartney, 2018; Ironside & Winyard, 2018). While she lacks Claire’s confidence in these matters, she has it professionally. We come to learn that when Lucille’s clinical skills are not enough to win over her patients, she asserts herself and fights for her ability to do her job (Ironside & Winyard, 2018). Like Claire, Lucille is neither all good or all evil, but rather a compelling, imperfect person (Sutton, 2018).

Issue 3: How Nurse Characters Provide Which Types of Clinical Care

Routinely in healthcare dramas and comedies, nurses have been depicted as the physician’s helper or handmaiden (Buresh & Gordon, 2006; Turow, 2012). These portrayals fuel opinions that nurses have low status, are inferior to physicians, lack autonomy (Glerean et al., 2017), are unintelligent, depend on physicians for direction, and only follow orders due to their lower “place” in the power hierarchy. This troupe is particularly common in assumptions of nursing among the public (Cabaniss, 2011; Summers & Summers, 2015) and does not distinguish among the different levels of education, credentials, or licenses of nurses (e.g., RN, Licensed Vocational Nurse, Nurse Practitioner).

Meanwhile, a stereotype of the super-capable nurse is at the opposite end of the spectrum. This savior nurse is able to act in almost any way, anytime, anywhere. While less common, shows with these idealized characters are less successful in media ratings and among critics (for a critique of TNT’s nurse-centric show, HawthoRNe, see Gilbert, 2009). The glaring problem here is that neither extreme works as a generalization of nursing or leads to particularly interesting storytelling.

In the story worlds of both Claire Temple and the midwives of CTM, the characters work outside the hospital which showcases their autonomy as clinicians engaged in problem solving in a variety of settings. We see Claire and the midwives seeking, valuing, and using input from more experienced nurses, physicians, mentors, and scientists. They are interdependent with other professionals but also autonomous in the field. They are intelligent despite having some inadequacies. This makes them more accurate representations of nursing and more interesting to the viewer.

Claire’s skill as a healer and a nurse scientist at the point of care involves working on the new frontiers of science with superhero issues and administering care in extreme situations. For example, at one point she is part of a group taken hostage within a nightclub. She escapes the immediate view of the captors to find and treat an injured Misty Knight in the club’s basement (Taylor & Tillman, 2016). Claire quickly assesses extreme clinical situations like these and intervenes to assure safety for her patient while simultaneously identifying outcomes she wants to bring about. In the case of Misty Knight, Claire stitches up her wounds with the available materials, warning Misty that if she does not get help soon, she could lose her arm (Taylor & Tillman, 2016). Misty ignores Claire’s advice, continuing to engage in police work even after the hostage situation has ended, eventually losing her arm and proving the accurateness of Claire’s assessment (Coker & Liu, 2018; Cooper, Murray & Abraham, 2016; Croal, Coker, & Johnson, 2016). Claire’s ability is depicted as strong but not boundless; she cannot save Misty’s arm (Coker & Liu, 2018) or speed up the effects of physical therapy once it is lost (Cooper & Green, 2018). In other scenes, she cannot keep Scarfe alive (Jackson & Miller, 2016) and she fails to convince Luke to reunite with his father (Cooper & Green, 2018). She is a fallible human being even though she is a skilled nurse.

While Claire exists in a 21st century world, treating people with special abilities and facing the challenges of a futuristic frontier of healing, the nurses in CTM practice midwifery in the past and are limited by the science of the time. For example, we watch as the characters discover that smoking is linked to cancer (Warner & Clarke, 2016) and that thalidomide is linked to birth defects in children (Thomas & Martin, 2016). This context is further enriched as we witness the exploration of methods of midwifery that were new at the time like breathing techniques and “calming” gas (Thomas & Lowthorpe, 2013; Warner & May, 2014).

The limitations of their time notwithstanding, the nurses of CTM offer invaluable care to patients. One particularly poignant example occurs in Series 4, Episode 5 (Bonnyman & Leclerc, 2015). Here, Dr. Turner (nurse Shelagh’s husband) becomes ill so Shelagh (formerly Sister Bernadette) decides to run his clinic herself. In doing this, she is attempting to protect her husband and serve patients at the same time. We see her triaging a waiting room full of people, adroitly deciding who she (and the backup nurse she secured) can treat and who must be referred. Along the way she encounters challenges, including the skepticism of patients accustomed to seeing the physician. To address these concerns, she takes precious time to get back into her nursing uniform, donning a symbol of the power of her skills, knowledge, and professional role. This inspires trust on the part of the patients and she is able to meet her goal of helping both her patients and her ailing husband.

Discussion and Future Implications

The breaking of stereotypes and presentation of positive but complicated depictions of nursing can only be good for the profession.The breaking of stereotypes and presentation of positive but complicated depictions of nursing can only be good for the profession. In these two productions, Claire and the CTM midwives are not saviors or handmaidens, angels or battle axes, sexpots or asexual prudes. They are complex, interesting human beings who we want to watch, who we root for, who we want to follow. They avoid each of the three challenging issues McHugh (2012) identifies as problems for scriptwriters, directors, and producers.

In terms of the first issue of reductive presentation of gender and sexuality, Claire Temple and the midwives demonstrate that compelling media can be made that does not reduce nursing professionals (and women) to sexual objects to be used at men’s discretion. Instead these portrayals give ample evidence of who these women are as people, averting the objectification of women that contributes to sexual harassment, abuse, and assault in the world today.

In relation to the second issue of reductive presentation of motivation, the Marvel universe and that of CTM imbue their characters with reasonable and substantial motives, creating complex and interesting why’s for each nurse and midwife character. They also give audiences permission to relate to nurses as imperfect, interesting people. This gives viewers who are nurses themselves more freedom to embrace their whole humanity rather than try to conform to a stereotype.

Finally, in relation to the third challenging issue of inaccurate representations of actual nursing work, both franchises portray nursing and midwifery as a complex, science-based profession, focused on caring with clinical skill and healing with a commitment to social justice. This work extends far beyond the hospital, exposing compelling aspects of the nursing profession and how it is actually practiced. They thus give viewers more accurate insight into the richness of nursing as a profession and its value in the world today.

Compelling media that heightens society’s understanding of and value for nursing can contribute to women’s empowerment within and beyond the clinical world.Compelling media that heightens society’s understanding of and value for nursing can contribute to women’s empowerment within and beyond the clinical world. By depicting the who, why, and how of these characters, Claire Temple and the midwives of CTM disrupt the old troupes in ways that could attract, engage, and influence young people, including people of color, to choose nursing as a career. With nursing work traditionally equated with femininity (McHugh, 2012), there is a distinct feminist value in not only creating but also consuming media that depicts nursing and women in ways that reflect reality and refute the assumption that women and nurses are “less than.” Watching these women characters doing clinical work, audiences get the impression that nursing is both important and often autonomous, offering an important contrast to the old troupes.

Taking Action

Nurses do not have to be alone in this struggle.We applaud the creators behind Claire Temple and CTM for demonstrating the viability of nurse characters that defy the caricatures and stereotypes too often employed historically and today. We urge more writers and media production teams to create increasing numbers of nuanced nurse and women characters and we urge you, our fellow audience members, to join us. For a robust discussion on the state of nursing in media and toolkits on how nurses in particular can take action, please visit The Truth About Nursing at truthaboutnursing.org. Here you can also learn about their new initiative, The Coalition for Better Understanding of Nursing (Truth About Nursing, 2018).

Nurses do not have to be alone in this struggle. We can join with a growing coalition of trade groups within the entertainment industry, working to advance women’s representation. Examples of these groups include:

- The Alliance of Women Directors: Founded in 1997, The Alliance of Women Directors is “an inclusive collective of over 250 professional women-identifying and gender nonbinary directors working together to affect positive, lasting change in the entertainment industry” (Alliance of Women Directors, 2018).

- Cherry Picks: Film critics are overwhelmingly men and this gender imbalance has wide reaching consequences for the entertainment industry, ensuring that the male perspective is a primary force in entertainment gate-keeping even as audience members are at least 50% female. Cherry Picks seeks to address this imbalance by organizing “a place to go to see how media and entertainment looks through a female lens” (Cherry Picks, 2018).

- Film Fatales: Focusing on the pivotal position of the director, Film Fatales “supports an inclusive community of women feature film and television directors who meet regularly to share resources, collaborate on projects and build an environment in which to make their films” (Film Fatales, 2018).

- Free the Bid: Working to increase the sustainability of women entering and staying in the directing profession, Free the Bid advocates “on behalf of women directors for equal opportunities to bid on commercial jobs in the global advertising industry” (Free the Bid, 2018).

- The Representation Project: “Using film and media as catalysts for cultural transformation, The Representation Project inspires individuals and communities to challenge and overcome limiting stereotypes so that everyone – regardless of gender, race, class, age, religion, sexual orientation, ability, or circumstance – can fulfill their human potential” (The Representation Project, 2018).

- TIME’S UP: Legal Defense Fund: “The TIME'S UP Legal Defense Fund is a place where survivors of sexual harassment or abuse in the workplace can get the legal help and public relations support they need to take back their power, seek justice, and make their voices heard” (TimesUp, 2018).

- Women and Hollywood: Founded in 2007 by Melissa Silverstein, Women and Hollywood “educates, advocates, and agitates for gender diversity and inclusion in Hollywood and the global film industry” (Women and Hollywood, 2018).

- Women’s Media Summit: The Women’s Media Summit is an annual convening of “movie-makers, academics, lawmakers, business professionals and supporters to build strategies that end gender inequity in American film and television” (Women’s Media Summit, 2018).

By speaking up in solidarity, we can move the needle on which stories get told and by whom.Nurses can become pivotal in this broader movement. We can collaborate with our allies and use our positions as women-viewers, nurse-viewers, and/or feminist-viewers to advocate for better, more meaningful representation. An informed audience teamed with activists and content creators is a powerful combination. Nurses, over three million strong in the United States alone (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2018), are a force with whom to reckon. By speaking up in solidarity, we can move the needle on which stories get told and by whom. The creators of Claire Temple, RN and CTM get it right and their positive message is one to celebrate, propagate, and champion.

Authors

Cristina Escobar, BA

Email: cristina@cescobarandrade.com

A communications and marketing consultant, Cristina Escobar has worked for feminist causes for over a decade, addressing the issues she cares about most. Escobar recently completed three and a half years as Director of Communications for The Representation Project. There, she hosted a national conversion around gender norms, reaching 2.5 million people a week and engaging up to 10% of them. Prior to joining The Representation Project, Ms. Escobar spent eight years at the national domestic violence prevention agency, Break the Cycle, including as Deputy Director. In her tenure, she more than doubled website traffic to the group, oversaw seven-figure donations, and ran initiatives ranging from after-school programs to public awareness campaigns. A leader in the gender equality movement, Ms. Escobar co-founded the Women Illuminated Film Festival, created and serves as the principal of Cristina Escobar Andrade Consulting, and writes on current issues with a feminist lens. She is particularly proud of having co-founded Mujeres Problemáticas, a blog critiquing film and media from a Latina perspective. Discussing issues ranging from domestic violence to women’s representation in media, Ms. Escobar has been featured in the Associated Press, Anderson Cooper Live, CNN, NPR, Mic, Refinery29, and more. She has also presented at events such as the Women’s March Women’s Convention, the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women, and the Women’s Media Summit. She earned a BA in English Literature and Spanish from Occidental College and a certificate in nonprofit leadership and management from Austin Community College.

MarySue V. Heilemann, PhD, RN, FAAN

Email: mheilema@ucla.edu

MarySue V. Heilemann, an associate professor at the UCLA School of Nursing, has pioneered the use of transmedia storytelling to create character-driven, evidence-based mental health interventions to broach stigmatized topics in user-friendly ways that are discreetly accessible via smartphones. She is an expert in transmedia and qualitative research methodology. Dr. Heilemann’s scholarship also includes a focus on improving the accuracy of nursing portrayals in film and television; she has led national symposia, guest edited a special volume of Nursing Outlook, consulted with Hollywood producers, and given various keynote speeches (including at the National Institute of Nursing Research) on the implications of inaccurate media portrayals of nurses. Dr. Heilemann was selected to be an official delegate to the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women in March 2018 in New York due to her work related to women and communication technologies. There she spoke on a panel on media and the global nursing shortage, and also her mental health transmedia production was screened. Based on her three-fold area of expertise (media-based interventions, methodologically-driven qualitative research, and mental health), Dr. Heilemann is actively refining a new model for nursing science that features transmedia portrayals of nurses in interventions to enhance the health of patients and the public. Dr. Heilemann completed a BSN degree at the University of Wisconsin and both an MSN and PhD at the University of California, San Francisco. She is a fellow of the American Academy of Nursing.

References

Alliance of Women Directors. (2018, October). Who we are. Retrieved from https://www.allianceofwomendirectors.org/about/

American Psychological Association, Task Force on the Sexualization of Girls. (2007). Report of the APA Task Force on the Sexualization of Girls. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/pi/women/programs/girls/report-full.pdf

Amidi, A. (2016, April 14). Cartoons that might no longer be appropriate in 2016: ‘Animaniacs.’ Cartoon Brew. Retrieved from https://www.cartoonbrew.com/ideas-commentary/cartoons-might-no-longer-appropriate-2016-animaniacs-138850.html

Barbee, E. L. (1993). Racism in U.S. nursing. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 7(4), 346-362.

Baugher, L. (2018). The 11 most important moments in Luke Cage season 2. Culturess. Retrieved from https://culturess.com/2018/06/28/the-11-most-important-moments-in-luke-cage-season-2/

Bonnyman, C. (Writer), & Leclerc, D. (Director). (2015, February 15). Series 4, episode 5 [Television series episode]. In A. Tricklebank (Producer), Call the Midwife. London: BBC.

Brockes, E. (2013, April 26). Call the Midwife: An unexpected PBS hit with another Brit import. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/emma-brockes-blog/2013/apr/26/call-the-midwife-pbs-hit-import

Buchan, J., & Aiken, L. (2008). Solving nursing shortages: A common priority. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 17, 3262-3268. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02636.x

Buresh, B., & Gordon, S. (2006). From silence to voice: What nurses know and must communicate to the public (2nd ed.). Ithaca, NY: ILR Press.

Cabaniss, R. (2011). Educating nurses to impact change in nursing's image. Teaching and Learning in Nursing, 6(3), 112–118.

Cherry Picks. (2018, October). Who we are. Retrieved from https://www.thecherrypicks.com/about

Coker, C.H. (Writer), & Liu, L. (Director). (2018, June 22). Soul brother #1 [Television series episode]. In G. Barringer & A. Cooper (Producers), Luke Cage. New York: Netflix.

Cooper, A. (Writer), & Green, S. (Director). (2018, June 22). Straighten it out [Television series episode]. In G. Barringer & A. Cooper (Producers), Luke Cage. New York: Netflix.

Cooper, A. (Writer), Murray, C. (Writer), & Abraham, P. (Director). (2016, September 30). Soliloquy of chaos [Television series episode]. In G. Barringer & A. Cooper (Producers), Luke Cage. New York: Netflix.

Croal, A. M. (Writer), Coker, C. H. (Writer), & Johnson, C. (Director). (2016, September 30). You know my steez. [Television series episode]. In G. Barringer & A. Cooper (Producers), Luke Cage. New York: Netflix.

Dill, J., Erickson, R. J., & Diefendorff, J. M. (2016). Motivation in caring labor: Implications for the well-being and employment outcomes of nurses. Social Science & Medicine, 167, 99-106. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.07.028

Film Fatales. (2018, October). Film fatales. Retrieved from http://www.filmfatales.org/

Free the Bid. (2018, October). Free the bid. Retrieved from https://www.freethebid.com/

Gibb, A. (Writer), & Macartney, S. (Director). (2018, March 4). Series 7, episode 7 [Television series episode]. In A. Tricklebank (Producer), Call the Midwife. London: BBC.

Gilbert, M. (2009, June 16). Nurse Hawthorne is too good to be true. The Boston Globe. Retrieved from http://archive.boston.com/ae/tv/articles/2009/06/16/nurse_in_hawthorne_too_good_to_be_true/

Glerean, N., Hupli, M., Talman, K., & Haavisto, E. (2017). Young peoples’ perceptions of the nursing profession: An integrative review. Nurse Education Today, 57, 95-102. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2017.07.008

Gordon, S. (2006). Nursing against the odds: How health care cost cutting, media stereotypes, and medical hubris undermine nurses and patient care. Ithaca, NY: IRL Press.

Heilemann, M.V., Brown, T., & Deutchman L. (2012). Making a difference from the inside out. Nursing Outlook, 60(5Suppl.), S47-54. doi:10.1016/j.outlook.2012.06.017

Heilemann, M.V. (2012). Media images and screen representations of nurses. Nursing Outlook, 60(5Suppl.), S1-3. doi:10.1016/j.outlook.2012.04.003

Horwitch, J. (Writer), & Jobst, M. (Director). (2016, September 30). Just to get a rep [Television series episode]. In G. Barringer & A. Cooper (Producers), Luke Cage. New York: Netflix.

Horwitch, J. (Writer), & Surjik, S. (Director). (2016, September 30). Take it personal [Television series episode]. In G. Barringer & A. Cooper (Producers), Luke Cage. New York: Netflix.

Horst, L. (1977). Bitches, twitches, and eunuchs: Sex-role failure and caricature. Lex Et Scientia, 13(1-2), 14-17.

How to avoid creating female character stereotypes in your writing. (n.d.) Retrieved October 2018 from https://www.wikihow.com/Avoid-Creating-Female-Character-Stereotypes-in-Your-Writing

Internet Movie Database. (2018, October). Rosario Dawson. Retrieved from https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0206257/

Ironside, L. (Writer), & Sullivan, E. (Director). (2018, February 25). Series 7, episode 6 [Television series episode]. In A. Tricklebank (Producer), Call the Midwife. London: BBC.

Ironside, L. (Writer), & Winyard, C. (Director). (2018, January 28). Series 7, episode 2 [Television series episode]. In A. Tricklebank (Producer), Call the Midwife. London: BBC.

Jackson, N.L. (Writer), & Miller, S. (Director). (2016, September 30). Suckas need bodyguards [Television series episode]. In G. Barringer & A. Cooper (Producers), Luke Cage. New York: Netflix.

Jepsen, C. (2018, July 10). How to avoid stereotypes and clichés. The Writing Cooperative. Retrieved from https://writingcooperative.com/how-to-avoid-stereotypes-and-clich%C3%A9s-9c241273cc96

Kaiser Family Foundation. (2018). Total number of professionally active nurses. Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/total-registered-nurses/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

Kalisch, B., Begeny, S., & Neuman, S. (2007). The image of the nurse on the internet. Nursing Outlook, 55, 182-188.

Kalisch, P. A., & Kalisch, B. J. (1987). The changing image of the nurse. Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley.

Kelly, A.N. (2018, October 1). Rosario Dawson likes Bosslogic’s Night Nurse idea (if Marvel is listening). Newsweek. Retrieved from https://www.newsweek.com/night-nurse-series-claire-temple-rosario-dawson-marvel-netflix-bosslogic-1147233

Kitie, B. (1999). The mass appeal of The Practice and Ally McBeal: An in-depth analysis of the impact of these television shows on the public's perception of attorneys. UCLA Entertainment Law Review, 7(1), 169-187. Retrieved from https://cloudfront.escholarship.org/dist/prd/content/qt9t888611/qt9t888611.pdf

Lauzen, M. M. (2018, September). Boxed In 2017-18: Women on screen and behind the scenes in television (2017-18 Report). Retrieved from the Center for the Study of Women in Television & Film website: https://womenintvfilm.sdsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/2017-18_Boxed_In_Report.pdf

Lugo, S. (2015, October 2). Hypersexualization of women of color in contemporary media. The Trail. Retrieved from http://trail.pugetsound.edu/?p=12888

Mason, D.J., Glickstein, B., & Westphaln, K. (2018). Journalists' experiences with using nurses as sources in health news stories. American Journal of Nursing, 118(10), 42-50. doi:10.1097/01.NAJ.0000546380.66303.a2

McHugh, K. (2012). Nurse Jackie and the politics of care. Nursing Outlook, 60(5 Suppl), S12-8. doi:10.1016/j.outlook.2012.06.003

NINRnews (2015, July 24). From the silver screen to the web: Portrayals of nurses in media [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZogLtLIr0aQ

Nussbaum, E. (2016, June 20). Crowning glory: The sneaky radicalism of “Call the Midwife.” The New Yorker. Retrieved from https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/06/20/call-the-midwife-a-primal-procedural

O’Brien P., & Gostin L.O. (2011). Health worker shortages and global justice (Report). Retrieved from Milbank Memorial Fund website: https://www.milbank.org/publications/health-worker-shortages-and-global-justice/

Oulton, J.A. (2006). The global nursing shortage: An overview of issues and actions [Supplemental material]. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice, 7(3), 34S-39S. doi:10.1177/1527154406293968

Owens, M. (Writer), & Jobst, M. (Director). (2018, June 22). Wig out. [Television series episode]. In G. Barringer & A. Cooper (Producers), Luke Cage. New York: Netflix.

Paige, R. (2015, April 17). 'Daredevil' Night Nurse Claire needs her own show & I've got 13 reasons that prove it. Bustle. Retrieved from https://www.bustle.com/articles/77011-daredevil-night-nurse-claire-needs-her-own-show-ive-got-13-reasons-that-prove-it

Pathways to Peace (2018). About Pathways to Peace. Retrieved from https://pathwaystopeace.org

The Representation Project. (2018, October). About The Representation Project. Retrieved from http://therepresentationproject.org/about/

Schulman, M. (2018).Louise Fletcher, Nurse Ratched, and the making of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest’s unforgettable villain. Vanity Fair.

Seago J.A., Spetz J., Alvarado A., Keane D., & Grumbach, K. (2006). The nursing shortage: Is it really about image? Journal of Healthcare Management, 51(2), 96-110.

Silverstein, M. (2013, January 18). New season of Call the Midwife to be directed only by women. Indiewire. Retrieved from https://www.indiewire.com/2013/06/new-season-of-call-the-midwife-to-be-directed-only-by-women-209099/

Stankiewicz, J. M., & Rosselli, F. (2008, January 15). Women as sex objects and victims in print advertisements. Sex Roles, 58(7), 579-589. doi:10.1007/s11199-007-9359-1

Summers, S., & Summers, H. J. (2015). Saving lives: Why the media’s portrayal of nursing puts us all at risk (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sutton, M. (2018, January 22). Call the Midwife viewers are completely taken with new recruit Nurse Lucille. Good Housekeeping. Retrieved from https://www.goodhousekeeping.com/uk/news/a574882/call-the-midwife-viewers-nurse-lucille-reaction/

Szymanski, D. M., Moffitt, L. B., & Carr, E. R. (2011). Sexual objectification of women: Advances to theory and research. The Counseling Psychologist, 39(1), 6-38. doi:10.1177/0011000010378402

TIME’S Up Legal Defense Fund. (2018, October). Time’s Up Legal Defense Fund home page. Retrieved from https://www.timesupnow.com/

Taylor, C. (Writer), & Shankland, T. (Director). (2016, September 30). DWYCK. [Television series episode]. In G. Barringer & A. Cooper (Producers), Luke Cage. New York: Netflix.

Taylor, C. (Writer), & Tillman, G. (Director). (2016, September 30). Now you’re mine. [Television series episode]. In G. Barringer & A. Cooper (Producers), Luke Cage. New York: Netflix.

Thomas, H. (2012). The life and times of Call the Midwife: The official companion to season 1 and 2. New York, NY: Harper Design.

Thomas, H. (Writer), & Lowthorpe, P. (Director). (2013, January 20). Series 2, episode 1. [Television series episode]. In H. Warren (Producer), Call the Midwife. London: BBC.

Thomas, H. (Writer), & Martin, D. (Director). (2016, March 6). Series 5, episode 8. [Television series episode]. In A. Tricklebank (Producer), Call the Midwife. London: BBC.

Thomas, H. (Writer), & Moo-Young, C. (Director). (2013, February 17). Series 2, episode 5. [Television series episode]. In H. Warren (Producer), Call the Midwife. London: BBC.

Thomas, H. (Writer), & O'Sullivan, T. (Director). (2014, December 25). Christmas special. [Television series episode]. In A. Tricklebank (Producer), Call the Midwife. London: BBC.

Thomas, H. (Writer), & Sharrock, T. (Director). (2013, December 25). Christmas special. In H. Warren (Producer), Call the Midwife. London: BBC.

Thomas, H. (Writer), & Spiro, M. (Director). (2013, March 10). Series 2, episode 8. [Television series episode]. In H. Warren (Producer), Call the Midwife. London: BBC.

Thomas, R. (2013, April 11). Storyville: Ten ways to avoid cliches and stereotypes. Lit Reactor. Retrieved from https://litreactor.com/columns/storyville-ten-ways-to-avoid-cliches-and-stereotypes

Truth About Nursing. (2018). The Truth about Nursing: Changing how the world thinks about nursing. Retrieved from https://www.truthaboutnursing.org/index.html#gsc.tab=0

Turow, J. (2012). Nurses and doctors in prime time series: The dynamics of depicting professional power. Nursing Outlook, 60(5 Suppl), S4-11. doi:10.1016/j.outlook.2012.06.006

21st Century Fox, the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media, and J. Walter Thompson Intelligence. (2018). The “Scully Effect”: I want to believe… in STEM (Report). Retrieved from 21CF Social Impact website: https://impact.21cf.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2018/03/ScullyEffectReport_21CF_1-1.pdf

United States Census Bureau. (2017). Quick facts [Data file]. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/SEX255217#viewtop

Warner, H. (Writer), & Clarke, L. (Director). (2016, February 14). Series 5, episode 5. [Television series episode]. In A. Tricklebank (Producer), Call the Midwife. London: BBC.

Warner, H. (Writer), & May, J. (Director). (2014, January 26). Series 3, episode 2. [Television series episode]. In H. Warren (Producer), Call the Midwife. London: BBC.

Warner, H. (Writer), & Spiro, M. (Director). (2013, March 3). Series 2, episode 7. [Television series episode]. In H. Warren (Producer), Call the Midwife. London: BBC

Weaver, R., Salamonson, Y., Koch, J. & Jackson, D. (2013). Nursing on television: Student perceptions of television's role in public image, recruitment and education. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 69(12), 2635–2643.

Williams, J. (Writer), & Moo-Young, C. (Director). (2013, February 14). Series 2, episode 6. [Television series episode]. In H. Warren (Producer), Call the Midwife. London: BBC.

Women and Hollywood. (2018, October). About Women and Hollywood. Retrieved from https://womenandhollywood.com/about/

Women’s Media Summit. (2018, October). About The Women’s Media Summit. Retrieved from http://www.womensmediasummit.org/about

World Health Organization. (2018, February). Nursing and midwifery fact sheet. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/nursing-midwifery/en/