The Data, Information, Knowledge and Wisdom Model (Nelson D-W) depicting the megastructures and concepts underlying the practice of nursing informatics was included for the first time in the 2008 American Nurses Association (ANA) Scope and Standards of Practice for Nursing Informatics (ANA, 2018). The date of this publication was almost 20 years after the first version of the model had been published. In 1989, a colleague and I wrote a brief article defining the concepts of data, information, knowledge, and wisdom. (Nelson & Joos, 1989 Fall). At that time, the three concepts of data, information, and knowledge were well established in the field of information science and had been introduced in the emerging discipline of medical informatics. However, adding the concept of wisdom to these three concepts and defining how wisdom was related to the established concepts was new. Part 1 of this two-part Informatics Column will focus on the addition of wisdom to the model. Part 2 will explore how the model has changed in the almost 30 years since this first brief article.

Two driving forces interacting together led to my decision to include wisdom as part of the model. First, in the summer of 1988, I completed a post-doc in nursing informatics with Judy Graves at the University of Utah. Dr. Graves had just transitioned to the university where she was establishing one of the first graduate programs in nursing informatics. Under Dr. Graves’ direction, each of the four post-doc students that summer were immersed in an educational process based on defining the practice of nursing informatics starting with the concepts of data, information, and knowledge. Dr. Graves was also busy writing an article that would become one of the seminal articles in the nursing literature.

In 1989, Judith Graves and Sheila Corcoran published their article using the concepts of data information and knowledge in defining nursing informatics as a scientific discipline. “The working definition of nursing informatics [is] the study of the management and processing of nursing data, information and knowledge” (Graves & Corcoran, 1989, p. 228). The article also provided a conceptual model that was “intended to serve as a model for understanding the relationships between the concepts and procedural knowledge” (Graves & Corcoran, 1989, p. 228). The model presented the three concepts of nursing data, information and knowledge in a linearly relationship with data leading to information and information leading to knowledge. Procedural knowledge involves knowing how to do something. For example, knowing how to assess a patient’s breath sounds requires procedural knowledge. In the Graves model, management processing is the procedural knowledge used to process data, information, and knowledge.

As Graves and Corcoran point out in their article, the model was built on the work of Bruce Blum. “This framework for nursing informatics relies on a taxonomy and definitions of the central concepts of data, information and knowledge put forward by Blum (1986)” (Graves & Corcoran, 1989, p. 227). Blum had previously defined the concepts of data, information and knowledge in discussing the discipline of medical informatics (Blum, 1986). One of his goals was to explain that the discipline could not be defined by information technology that is used in the practice on medical informatics, but rather the discipline of informatics is defined by how the provider uses technology to meet human needs. “The emphasis is on the medical use of the information technology and not on the application of technology to medicine” (Blum, 1989, p. 24). In making his point, Blum defined three objects that could be processed by information technology.

- Data – uninterpreted items, often referred to as data elements. An example might be a person’s weight. Without additional data elements such as height, age, overall well-being it would be impossible to interpret the significance of an individual number.

- Information – a group of data elements that have been organized and processed so that one can interpret the significance of the data elements. For example, height, weight, age, and gender are data elements that can be used to calculate the BMI. The BMI can be used to determine if the individual is underweight, overweight, normal weight or obese.

- Knowledge is built on a formalization of the relationships and interrelationships between data and information. A knowledge base makes it possible to understand that an individual may have a calculated BMI that is over 30 and not be obese. At this time, several automated decision support systems included a knowledge base and a set of rules for applying the knowledge base in a specific situation. For example, the knowledge base may include the following information. A fever or elevated temperature often begins with a chill. At the beginning of the chill the patient’s temperature may be normal or even sub-normal but in 30 minutes it is likely the patient will have spiked a temp. A rule might read: if a patient complains of chills, then take the patient’s temperature and repeat in 30 minutes.

The second driving force came from my experience as a university faculty member in a clinical setting. When I returned in the fall 1988 to my faculty position, this literature and these concepts building the foundation of nursing informatics were well engraved in my thinking.

One of my primary responsibilities as a faculty member was teaching medical surgical nursing to senior nursing students in the classroom and the clinical setting. The clinical setting was in a major medical center. The nursing staff in this unit were excellent and provided outstanding role models for students. The patients were acutely ill with major medical problems. In other words, it was an ideal setting for teaching senior nursing students.

During this fall term one of the patients on this clinical unit had a major impact on my thinking about the concepts of data information and knowledge. The patient was a young woman who had delivered her first child and had been immediately transferred to the medical center with a variety of serious medical problems and related symptoms including high volume congestive heart failure, 4 plus edema and pulmonary effusion. One year earlier she had been fully heathy and planning her first pregnancy. Shortly after admission to our unit she was diagnosed with a terminal illness. Caring for such a patient is always a heart wrenching challenge.

The students and I worked closely with the staff in providing quality care for this patient, but one thing was obvious to me from the first day. Experienced staff seems to be intuitive in how to provide both physical and emotional care. They knew what to say and what to leave unsaid. They knew when to move forward and finish a difficult procedure such as deep suctioning and when to stop and let the patient rest. They were comfortable and confident in this role as caregiver. Students on the other hand were very uncomfortable. While they were dedicated in learning their role they were also very afraid of saying or doing the wrong thing. Before walking in the room, I would often see a student take a deep breath.

I suspect if we had given a theory-based test on the stages of death and dying to both students and staff the scores would be very similar. It is even possible that the students’ scores would be higher since they had studied this material more recently. But as my observations about the care of this patient demonstrated there is a difference between knowing something and being able to apply that knowledge to a specific situation. Data can be processed to produce information. Data and information are the building blocks for creating knowledge. But the practice of nursing and in turn the practice of nursing informatics occurs when data, information and knowledge are used to meet the health needs of individuals, families, groups and communities.

The more I considered what I was seeing on the clinical unit and what I understood about the conceptual framework of nursing informatics, the more I felt that the model was not complete. A part of the picture was missing. The data, information and knowledge that nurses use is the foundation on which nursing educational programs are built and in turn is the foundation for the practice of nursing. But the practice of nursing is defined by how nurses use data, information and knowledge in providing care. The wisdom of nursing is demonstrated when the nursing data, information and knowledge are managed and used in making appropriate decisions that meet the health needs of individuals, families, groups and communities. While these concepts do not require technology, the practice of nursing informatics does require technology. The practice of nursing informatics uses “information structures, information processes and information technology” to support this practice. (American Nurses Association, 2015, p. 2) As Blum pointed out decades ago, the technology does not define the practice but rather the practitioners’ use of technology defines the practice.

When the concept of wisdom was first proposed several experts in the field questioned whether the concept belonged in the model depicting the conceptual framework for nursing informatics. For example, the 2001 edition of the ANA Nursing Informatics: Standards and Scope of Practice included the following statement:

The Future of Nursing Informatics

After the Graves and Corcoran (1989) article, others proposed adding the concept of wisdom to the triad of data, information, and knowledge (Nelson and Joos, 1989). Wisdom may be defined as the appropriate use of data, information, and knowledge in making decisions and implementing nursing actions. It includes the ability to integrate data, information, and knowledge with professional values when managing specific human problems.

Some nursing informatics (NI) experts believe strongly that wisdom is the purview of humans and cannot or should not be considered as a function within technology. Others believe that informatics solutions consistent with professional values and useful to expert nurses will require the incorporation of wisdom. This controversy makes the inclusion of wisdom into the triad of data, information, and knowledge currently an unresolved issue within NI. (American Nurses Association, 2001, p. 130)

For this author the question goes back to the original question that Blum raised. Is the scope of the practice defined by the functionality of the technology or by the practitioner’s use of the technology? This is not a simple question. The practice of informatics would not exist without the technology. In addition, the functionality offered by the technology has a strong influence on what practitioners can do with that technology. Information technology is necessary for the practice of nursing informatics but it is not sufficient to define the practice. In a 2002 publication, I created a figure demonstrating how the different levels of information technology related to the concepts of data, information, knowledge and wisdom. (Englebardt & Nelson, 2002).

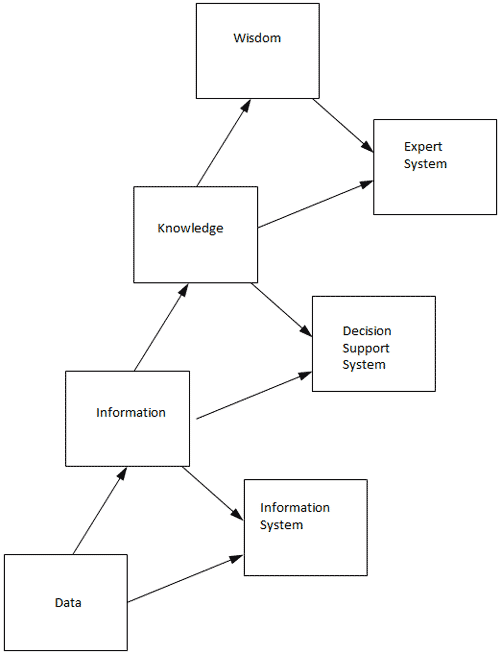

Figure 1. The Relationship of Data, Information, Knowledge, and Wisdom and Automated Systems: version 1

Credit: Copyright Ramona Nelson. Used with the permission of Ramona Nelson, President Ramona Nelson Consulting at ramonanelson@verizon.net and Sheila P. Englebardt. All rights reserved.

In the figure, an information system processes data to produce information. A decision support system is defined as an automated system that can support a decision maker in the process of decision making by providing data and information. An expert system goes one step farther and actually uses data and information to make a decision. A common example of an expert system in operation can be seen if one has ever opened a new credit card account while checking out of a store. In a few minutes an automated system makes a decision rather or not to offer credit. Historically these types of decisions were made by human beings based on information included in an application for a credit card as well as other sources of data. The judgement of credit worthiness of the customer depended on how a person interpreted that information and data. Today in many cases the decision concerning the creditworthiness of a customer has been automated.

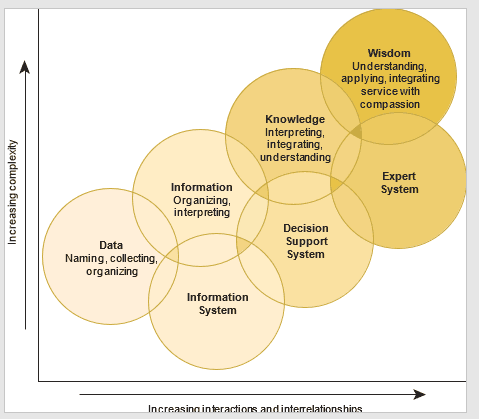

The first model, Figure 1, failed to clearly demonstrate the overlapping interrelationship between the concepts used in the model and the levels of technology as classified within the Figure. In response to this reality, Figure 2 was developed showing the overlapping interrelationships.

Figure 2. The Relationship of Data, Information, Knowledge, and Wisdom and Automated Systems: version 2.

Credit: Copyright Ramona Nelson. Used with the permission of Ramona Nelson, President Ramona Nelson Consulting at ramonanelson@verizon.net. All rights reserved.

There is no question that computers can process data yielding information. IBM’s Watson as well as other artificial intelligence (AI) based systems are demonstrating how automated systems can process information to create new knowledge. Today the amazing developments within applications based on AI the question becomes where does wisdom fit in automated systems?

While the new model does a better job of showing overlapping relationships there have been problems how this model is understood. There has been as least one textbook published that modified this figure and described their modification as the Nelson D-W model. I have been assured this error will be corrected with the second printing of that book. However, as a result of this error, I have been contacted by two doctoral students to date who are planning to use the Nelson D-W model in their doctoral dissertation research and have been confused by this error. Figure 2 as depicted here is used to illustrate how the concepts in the Nelson D-W model might interact with the various levels of information technology. It does not illustrate the relationships and interrelationships with the actual model. The evolution of the model as well as the relationships and interrelationships will be further explored in part 2 of this series.

Ramona Nelson, PhD, BC-RN, ANEF, FAAN

Email: ramonanelson@verizon.net

Dr. Nelson holds a baccalaureate degree in nursing from Duquesne University, and master’s degrees in both nursing and information science, as well as a PhD in education, from the University of Pittsburgh. Prior to her current position as President of her own consulting company, she was Professor and Chair of the Department of Nursing at Slippery Rock University in Pennsylvania. In the early 1980’s, one of Dr. Nelson’s employee benefits while teaching at the University of Pittsburgh was the opportunity to take university courses for only $5.00 a credit. After taking courses in computer assisted instruction and information science theory, she recognized these tools (computers) just might be somewhat useful at the bedside and in the classroom. She has been exploring and discovering just how useful they can be ever since.

Dr. Nelson’s more recent research and publications focus on the specialty area of health informatics. Her latest book, Health Informatics: An Interprofessional Approach (2018), co-authored with Nancy Staggers, received the second place American Journal of Nursing Book of the Year award for Information Technology/Informatics. The second edition continues today as a primary textbook in the field of health informatics. Based on her contributions to nursing and health informatics she has been inducted into both the American Academy of Nursing and the first group of fellows in the National League for Nursing Academy of Nursing Education. She has also been recognized as a pioneer within the discipline by the American Medical Informatics Association. Her goal in serving as Editor of OJIN’s Informatics Column is to open a discussion about how we as nurses in the inter-professional world of healthcare can maximize the advantages and manage the challenges that computerization brings to our practice.

References

American Nurses Association. (2001). Scope and Standards for Nursing Informatics Practice. Silver Spring, MD: Nursesbooks.org.

American Nurses Association. (2008). Nursing Informatics: Scope and Standards of Practice. Slivers Springs, MD: Nursesbooks.org.

American Nurses Association. (2015). Nursing Informatics: Scope and Standards of Practice. (2nd, Ed.). Silver Spring, MD: Nursingbooks.org.

Blum, B. (1989). Medical informatics - Phase II. In H. Orthner, & B. Blum (eds.), Implementing Health Care Information Systems (p. 24). New York, NY: Springer-Verlag,

Blum, B. L. (1986). Clinical Information Systems. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag.

Englebardt, S., & Nelson, R. (2002). Health care informatics: An interdisciplinary approach. St Louis, MO: Mosby, Inc.

Graves, J., & Corcoran, S. (1989 Winter). The study of nursing informatics. IMAGE: Journal of Nursing & Scholarship, 21(4), 227-231.

Nelson, R., & Joos, I. (1989 Fall). On language in nursing: From data to wisdom. PLN Vision, p. 6.