A Midwestern, 532-bed, acute care, tertiary, Magnet® designated teaching hospital identified concerns about fall rates and patient and nurse satisfaction scores. Research has shown that the implementation of bedside report has increased patient safety and patient and nurse satisfaction. An evidence-based practice change incorporating bedside report into standard nursing care was implemented and evaluated over a four-month time period on three nursing units. Fall rates, HCAHPS and Press Ganey® scores, and nurses’ response to a satisfaction survey were measured before and after the project implementation. This article begins with the background of the problem and literature review, and then presents the project methods, measures, and data analysis. Results demonstrated that patient fall rates decreased by 24%, and nurse satisfaction improved with four of six nurse survey questions (67%) having percentage gains in the strongly agree or agree responses following implementation of bedside report. HCAHPS and Press Ganey® results demonstrated improvement in Press Ganey® scores on two of the three nursing units. In this project, implementation of bedside report had a positive impact on patient safety, patient satisfaction, and nurse satisfaction. The authors conclude with discussion of findings and implications for nursing management.

Key Words: bedside report, shift report, handoff, patient safety, patient satisfaction, nurse satisfaction, evidence-based nursing practice, patient centered care, quality improvement, teamwork, work redesign, leadership, and organizational culture.

Hospital leaders and healthcare organizations are making concentrated efforts to change their environments to assure patient safety and patient and nurse satisfaction. In April 2011, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) enacted a hospital Value Based Purchasing (VBP) program that began to measure and pay for hospital quality performance (Medicare.gov, n.d.). By 2015, CMS focused on four domains: clinical process of care, patient experience of care, outcome, and efficiency. Patient safety and patient and nurse satisfaction are scored within these domains. For a health system to be successful and maintain its viability and future growth, patient safety and patient and nurse satisfaction are key components (Medicare.gov, n.d.).

Bedside shift report (BSR) enables accurate and timely communication between nurses, includes the patient in care, and is paramount to the delivery of safe, high quality care. Hospital leaders and healthcare organizations are making concentrated efforts to change their environments to assure patient safety and patient and nurse satisfaction. In the literature, changing the location of shift report from the desk or nurses’ station to the bedside has been identified as a means to increase patient safety and patient and nurse satisfaction. Shift report, when completed at the patient bedside, allows the nurse to visualize and assess the patient and the environment, as well as communicate with and involve the patient in the plan of care. Bedside shift report (BSR) enables accurate and timely communication between nurses, includes the patient in care, and is paramount to the delivery of safe, high quality care.

Background

A team of nursing administrators, directors, staff nurses, and a patient representative was assembled to review the literature and make recommendations for practice changes. A Midwestern, 532-bed, acute care, tertiary, Magnet® designated teaching hospital identified that fall rates were above the national average. Patient satisfaction, as measured by Press Ganey®, consistently scored below the target range of 90%, and the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) scores for questions related to nursing communication were below 85%, or the 90th percentile. Nurse satisfaction scores, as measured by the National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators (NDNQI), were 69.7%, below the overall goal of 75%. A team of nursing administrators, directors, staff nurses, and a patient representative was assembled to review the literature and make recommendations for practice changes. This article begins with the background of the problem and brief literature review, and then presents the project methods, measures, and data analysis. We conclude with results and discussion of our findings and implications for nursing management.

Literature Review

The team completed a literature review based upon the following PICO question: Does the implementation of BSR as compared to standard shift report at the nurses’ station increase patient safety and patient and nurse satisfaction? The practice of shift report at the bedside is not a new concept and is well documented in the literature. Numerous studies support the positive impact of BSR on patient fall rates, as well as patient and nurse satisfaction (Cairns, Dudjak, Hoffman, & Lorenz, 2013; Evans, Grunawalt, McClish, Wood, & Friese, 2012; Jeffs et al., 2013; Laws, & Amato, 2010; & Sand-Jecklin & Sherman, 2013).

Patient participation in the report is paramount to delivery of safe, high quality care. After the literature review, the team defined BSR as the accurate and timely communication between nurses and also between the nurses and the patient. Patient participation in the report is paramount to delivery of safe, high quality care. Furthermore, through reading and discussion of the articles, the team concluded that report, when completed at the patient bedside, allows the nurse to visualize and assess patients and the environment, with better communication and patient involvement in care.

Methods

The team completed a gap analysis to determine evidence-based best practices for shift report as compared to the current practice. Written approval to conduct the quality improvement project was obtained from the university and hospital institutional review boards (IRB). The team completed a gap analysis to determine evidence-based best practices for shift report as compared to the current practice. At baseline, shift report was done in a conference room, at the desk, or in the hallways. BSR was not a practice on any of the units. Report was not standardized, though all nurses had some preferred form of communication.

An organizational assessment completed using the strengths-weaknesses-opportunities-threats (SWOT) format revealed that the practice change to BSR was feasible and congruent with the hospital’s nursing model, Jean Watson’s theory of transpersonal caring (Watson, 1999), and Kristen Swanson’s middle range theory of caring (Swanson, 1993). The team selected the Iowa Model of Evidence-Based Practice to Promote Quality Care (Titler, 2011) and Kotter’s Eight Stage Process for Major Change (Kotter, 1996) to guide implementation and sustain progress. Tests of change in Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) cycles were used to evaluate the practice change in real-time and make necessary adjustments throughout implementation (The Deming Institute, n.d.).

Three units were selected for implementation of the practice change based upon the directors’ desire and willingness to participate. The populations served on the chosen nursing units were patients undergoing general surgery, and those with orthopedic and neuroscience diagnoses. Members of these units volunteered to be part of the BSR team.

Scripted Report

We incorporated fictitious patient information that aligned with typical patient conditions from each area. The team developed two scripts to use for report: one for medical units and one for surgical units. Scripts were created with input and consensus of staff, based upon the Introduction, Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation, Question (ISBARQ) format (Heinricks, Bauman, & Dev, 2012). We incorporated fictitious patient information that aligned with typical patient conditions from each area. See Figure 1 for a sample of script content. Confidential aspects of report (e.g., abnormal laboratory and radiology test results indicative of poor prognosis) that had not been discussed between the patient and physician were discussed nurse-to-nurse, prior to completing BSR.

Figure 1. Medical Unit Nurse Script

|

ISBARQ: Introduction, Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation, Questions INTRODUCTION: Off-going nurse introduce the oncoming nurse SITUATION: Patient name Reason for admission Code status BACKGROUND: Pertinent history Laboratory and X-ray results Other testing results Consults ASSESSMENT: Assessment to include pertinent findings for assigned patient population Medications and treatments Pending tests White board update Safety and Environmental Check IVs, Drains, Pain Mobility Environmental scan: clutter, side rails, visual assessment of room safety RECOMMENDATION: Pertinent information from Plan of Care Follow up tests to be completed QUESTIONS: Thank the patient and ask if he/she has any questions. |

Education

Staff education included reading two journal articles (Cairnes, Dudjak, Hoffman, & Lorenz, 2013, and Evans, Grunawalt, McClish, Wood, & Friese, 2012), and watching a recorded clip created by the team (six staff nurses, two directors, two video personnel) to demonstrate the BSR process. The clip utilized the scripts used in the training of staff. Educators helped to determine the information that should be shared confidentially via nurse-to-nurse communication and what was to be included in BSR.

The BSR began with the outgoing nurse introducing the oncoming nurse to the patient, followed by an assessment of the patient and environment. The BSR began with the outgoing nurse introducing the oncoming nurse to the patient, followed by an assessment of the patient and environment. The patient assessment included a general overview of the patient’s condition and significant aspects of care (e.g. wound sites; dressings; abnormal breath or heart sounds; intravenous sites, solutions, and rates; or anything considered out of the ordinary). Nurses surveyed the room for safety issues, including the bed and side-rail position and presence of clutter, and ensured that necessary items were within patient reach. Prior to leaving the room, they updated the white board in the room, reviewed pain medications, and inquired of patients, “Do you have any questions?” Following the education, staff members were given script cards to use during report. They had time to practice giving report using the ISBARQ format before demonstrating competency to a staff champion or BSR team member.

Tests of Change

The PDSA framework was utilized throughout the project and allowed staff input into the ongoing process of BSR. The PDSA framework was utilized throughout the project and allowed staff input into the ongoing process of BSR. During implementation of the project, we identified multiple items that required small process changes or what are called “linked process changes” (Taylor et al. 2013, p.5). These are defined as “two or more (PDSA) cycles with lessons learned from one cycle linking and informing a subsequent cycle” (Taylor et al. 2013, p.5).

One example of a linked change that occurred was script changes based upon the patient; nurse familiarity with the history; and management of patient requests for privacy. Staff members were encouraged to discuss BSR process issues with BSR team members, who made frequent rounds throughout the project. To maintain consistency, suggested changes were discussed with BSR team members prior to implementation. Most requested changes were minor, such as asking patients how they would prefer to be addressed by staff. Changes were passed on to other nurses during unit rounds or through directors and champions at change of shift report.

Measures

Audits

A BSR audit tool was implemented to assure compliance to the BSR process, including verifying that report was completed at the bedside; introducing the oncoming nurse; scripting in ISBARQ; updating the white board; and reviewing care. Shift report time audits, measured from the beginning of report until all handover communication ended, were completed pre-implementation and post-implementation. A direct comparison of mean report times was completed on pre-implementation versus post-implementation shift times. An example of the audit report is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. BSR Shift Report Time Audit Tool

|

BSR Process Audit Tool |

Number of nurses/shift |

Time |

Report Shift/Date/Time |

|

Nursing Unit: |

|||

|

Number of Nurses /Shift |

|||

|

Report Start time |

|||

|

Report End time |

|||

|

Total time |

|||

|

Census |

|||

|

Auditor |

Falls

The number of patient falls was obtained through the hospital incident reporting system and converted into a fall rate using the standard calculation of 1,000 patient days: the total number of falls divided by the number of patient days times 1,000 (AHRQ, 2013). The number of falls in the four-month period before BSR implementation was compared to the number of falls in the four-month period following implementation of BSR.

Satisfaction Surveys

Patient satisfaction was measured by both Press Ganey® and HCAHPS and compared from the four months prior to implementation to the four months after implementation. Both patient satisfaction surveys were standard tools mailed to 50% of discharged patients from the hospital per survey criteria. As shown in Table 1, patient satisfaction was measured by using eight questions from the Press Ganey® survey (“Press Ganey® Survey”, 2015) and two questions from HCAHPS (HCAHPS Survey, 2015).

Table 1. Patient Satisfaction Survey Questions

|

Press Ganey® Questions

HCAHPS Questions

|

Nurse satisfaction with the report process was determined using surveys adapted with permission from previously published tools (Cairns et al. 2013; Evans et al. 2012). To assure question clarity and relevance of the project, surveys were completed by six members of the BSR team, three directors, and three staff. The baseline appraisal was an anonymous, six-question survey that employed a five-item Likert scale (5-strongly agree to 1-strongly disagree). The post-implementation survey asked the same six questions, plus an additional question about the top concern since BSR implementation. Participants were given pre-determined choices of increased time, patient confidentiality, convenience, or were permitted to write comments. Nurses providing care on the three units were invited to complete the electronic survey via email and in-person invitation.

Data Analysis

The software SPSS (IBM Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) version 22 was utilized to complete the data evaluation process. The analysis of patient satisfaction results was measured using independent samples t-test (two-tailed) to determine statistical significance of the data. Nurse satisfaction survey results and shift report times utilized the Mann-Whitney Utest. Patient fall rates were analyzed using the Chi-square test. Press Ganey®scores were analyzed by computing the mean score totals of eight specific questions related to patient satisfaction through comparison of data pre and post- implementation of BSR. HCAHPS scores were analyzed by computing mean score totals for two specific questions related to nurse communication through comparison of the data pre and post implementation of BSR.

Results

All nursing staff members (n=67) completed education prior to implementation of BSR. Performance audits of staff adherence to the tenets of the BSR process while giving report were completed on the three nursing units. The audit results revealed a combined compliance rate of 94% (n= 157). Overall time of the shift report, from the time the first nurse started report until all nurses had completed report, was measured pre-implementation and post-implementation of BSR. A total of 94 shift reports, 46 before and 48 after BSR implementation, were observed and timed. There was no statistically significant difference between mean time for report before and after implementation of BSR. Actual times for report were as follows: general surgery unit: 35.1 pre and 35.1 post; orthopedic unit: 31.5 pre and 29.6 post; and neuroscience unit: 51.8 pre and 51.6 post.

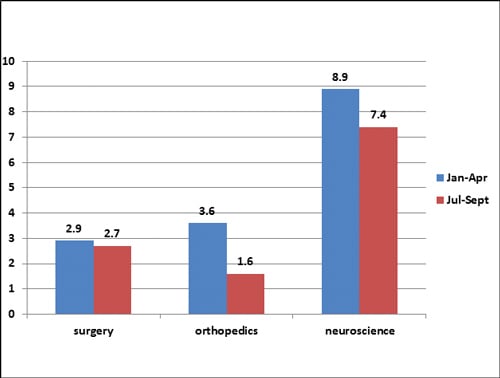

Patient falls decreased by 24% in the four months after BSR implementation compared to pre-implementation falls. The orthopedic unit experienced the greatest reduction in the number of falls at 55.6%, followed by the neuroscience unit at 16.9%, and the general surgery unit at a 6.9% reduction. Patient falls results are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Nursing Unit Falls Per 1,000 Patient Days

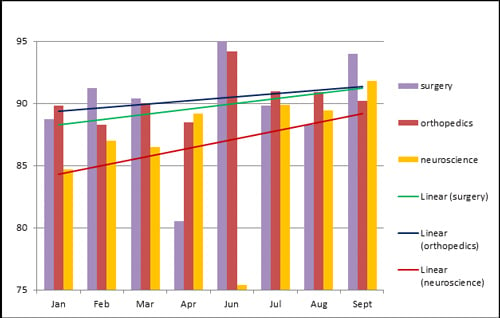

Figure 4 represents all three units’ scores, demonstrating improvement in patient satisfaction as measured by Press Ganey scores. Only the general surgery unit had statistically significant (p = 0.03) improvement in patient satisfaction after implementation of BSR with the average Press Ganey® score for the eight questions producing a result that increased from average score 87.7% to 91.6%. HCAHPS showed improvement, but the changes were not statistically significant.

Figure 4. Press Ganey® Eight Question Average Score

Sixty-four (95%) of the nurses completed the pre- implementation survey, and fifty-seven (85%) completed the post survey. Table 2 represents the number of nurses who reported having enough time for report was significantly decreased, from 80% pre BSR to 59.6% after implementation of BSR (p = 0.008). In the post survey, staff members were able to express concerns about BSR; 70% (n = 45) of the nurses who responded to this question believed that BSR increased the time it took to individually give and receive report. Thirty-nine percent (n=25) of staff reported concerns about patient confidentiality; 44% (n=29) responded that BSR was inconvenient for nurses due to many factors (e.g., multiple nurses needing report, patient requests delayed report, and nurses preferring the status quo).

Table 2. Nursing Survey Results

|

Question |

Level of Agreement |

Pre-BSR (n=65) |

Post BSR (n=57) |

Mann Whitney U standardized test statistic |

p value |

|

1. I have enough time to give and receive report |

Strongly agree Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly disagree |

10 (15.4%) 42 (64.6%) 9 (13.9%) 3 (4.6%) 1 (1.5%) |

4 (7%) 30 (52.6%) 4 (24.6%) 4 (7%) 5 (8.8%) |

-2.668 |

0.008 |

|

2. Shift report is concise and only contains information pertinent to the patients’ care |

Strongly agree Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly disagree |

14 (21.5%) 27 (41.5%) 14 (21.5%) 9 (13.9%) 1 (1.6%) |

4 (7%) 43 (75.4%) 14 (8%) 2 (3.5%) 0 |

0.797 |

0.426 |

|

3. Shift report format is standardized on my unit |

Strongly agree Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly disagree |

6 (9.3%) 31 (47.7%) 14 (21.8%) 11 (16.9%) 3 (4.6%) |

1 (1.8%) 31 (54.4%) 18 (31.6%) 7 (12.3%) 0 |

-0.025 |

0.980 |

|

4. My initial assessment of my patient(s) is consistent with the information I received in report (i.e. infusion rate, dressing change, mental status, etc.) |

Strongly agree Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly disagree |

14 (21.5%) 37 (56.9%) 12 (18.5%) 2 (3.1%) 0 |

2 (3.5%) 43 (75.4%) 12 (21.1%) 0 0 |

-1.482 |

0.138 |

|

5. Nurses on my unit are open to me asking them questions after I listen to their report |

Strongly agree Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly disagree |

22 (33.8%) 33 (50.8%) 7 (10.8%) 3 (4.6%) 0 |

22 (38.6%) 29 (50.9%) 6 (10.5%) 0 0 |

0.810 |

0.418 |

|

6. Nurses on my unit are available if I want to ask them questions after I listen to report |

Strongly agree Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly disagree |

17 (26.2%) 31 (47.8%) 13 (20%) 4 (6%) 0 |

15 (26.3%) 35 (61.4%) 5 (8.8%) 2 (3.5%) 0 |

1.051 |

0.293 |

|

7. My top concern(s) since the implementation of bedside shift report are:

Worth it/Good for the patient

Patient safety

Time efficiency

|

|||||

Discussion

Despite the perception that report took longer, many nurses commented that the extra time was worth it because they recognized the value of BSR for patient care. BSR was associated with decreased fall rates, and this finding is consistent with the literature (Jeffs et al. 2013; Sand-Jecklin & Sherman, 2013). Since falls occur for many reasons, it is not surprising that a single environmental scan at change of shift did not eliminate all falls. However, in one instance, nurses found a patient trying to climb out of bed during BSR and timely intervention may have prevented a fall. In the staff satisfaction survey, a nurse reported discovering a patient who had experienced a change in neurological status during BSR. It would be important to note in future studies or projects that the importance of the visual assessment component of the patient and the environment in BSR should be considered as an outcome measure.

Patient satisfaction was improved with BSR as measured by the Press Ganey® survey (Figure 4). This outcome is consistent with others in the literature (Laws et al., 2010; Evans et al., 2012; Maxson, Derby, Wrobleski, & Foss, 2012; Cairns et al., 2013; Jeffs et al., 2013; Sand-Jecklin & Sherman, 2014). The HCAHPS scores for the surgery and orthopedic units also showed a positive trend during the project. Though not statistically significant, improvements in patient satisfaction scores have clinical significance since they are value-based measures and are directly tied to reimbursement. Also, satisfied patients tend to talk about their experiences to others, recommend a facility to friends, and return as patients for future hospitalizations (Radke, 201; Mayer & Cates, 2014; Seagrist, 2013).

Implementation of BSR did not increase the average total time required for change of shift report, although individual nurses may have experienced longer report times. Nursing satisfaction surveys showed a decrease in nurses reporting that they had enough time to give and receive report. Of note, the top concern about BSR of one nurse was “patient requests during BSR,” and another reported, “…you can get stuck in the room….” Despite the perception that report took longer, many nurses commented that the extra time was worth it because they recognized the value of BSR for patient care.

Nurses made positive comments about BSR on the staff satisfaction survey, but reported a decline in consistency of the initial assessment with the assessment given in report. Examples of initial assessment inaccuracies included discovering empty intravenous bags or an IV site that had been changed during the shift but not properly documented. Another reason for different expectations for the initial assessment was patient decline in condition between the last time the outgoing nurse had been in the room and BSR.

Earlier identification and correction of potential errors during BSR may have improved the quality of patient care. Earlier identification and correction of potential errors during BSR may have improved the quality of patient care. Nurses reported an increase in availability and degree of openness to questions between outgoing and oncoming nurses, which has been associated with improved communication and quality of care (Cairns et al., 2013; Jeffs et al., 2013). Anecdotally, nursing staff members indicated that their own practice benefitted from the change to BSR because information gained during BSR allowed them to better prioritize patient care.

Implications for Nursing Management

BSR is a significant change to the current shift report practice and culture of most organizations, but it is associated with both improved patient safety and patient and nurse satisfaction. A limitation of this project was that the evidence-based quality improvement design prevents generalization of findings to other settings; however, the knowledge gained may be transferred to other units or hospitals.

Future projects should consider measuring communication and teamwork improvements related to BSR. The project had other limitations. Since an environmental scan for safety was part of BSR, fall rates were used to measure patient safety. However, results of the nurse surveys suggested that improvements to communication and teamwork, which affect patient safety, may have also been realized (Institute of Medicine, 2001). Future projects should consider measuring communication and teamwork improvements related to BSR. Since nurses reported spending time in the rooms giving care during BSR, it may be beneficial to have patient care assistants available during BSR.

Additionally, a system to track, measure, and evaluate the types of issues or errors found during BSR would be beneficial to further describe improvements to patient safety gained with BSR. For example, medication error reporting was not part of the project outcome measures, but was later identified as an issue discovered and mitigated during BSR. Nurses mentioned discovery of intravenous fluid concerns and possible medication inaccuracies during BSR, but these were not quantified in the audits or in the formal medication error reporting process. None of the inaccuracies were harmful or life threatening, but were the typical errors one finds in the majority of the hospitals that often may go unreported (Mayo & Duncan, 2004, Force et al., 2006). Future projects should consider exploring medication safety with the implementation of BSR.

Nursing leaders face implementation of numerous practice changes. This project focused on the immediate change period; however, maintaining the process and anchoring BSR into daily practice can be challenging. Caruso (2007), Evans et al. (2012), Cairns et al. (2013), Hagman et al. (2013), and Radke (2013) all commented on the difficulty of maintaining progress and overall sustainability of BSR. In this project, Kotter’s Eight Stage Process for Major Change (Kotter, 1996) was utilized to address the change process and facilitate ongoing compliance and sustainability of BSR on the pilot units. The final stage, called “anchoring” (p.21), is the ongoing priority for nursing leadership.

Sharing success stories... helps to encourage continued participation in BSR. Education is the beginning of obtaining buy-in from staff. Sharing success stories, such as the “good catch” of a patient who had deteriorated on rounds or improving fall rates, helps to encourage continued participation in BSR. Some staff members may initially participate but return to the nurses’ station for report unless nursing leadership continues to monitor performance and reinforce consistent expectations. When nurses explain that BSR is “how we practice,” BSR is “anchored” on your unit.

Authors

Edward R. McAllen, Jr., DNP, MBA, BSN, BA, RN

Email: ted.mcallen@akrongeneral.org

Edward R. McAllen, Jr. is the Director, Nursing Informatics at Cleveland Clinic Akron General in Akron, OH. Dr. McAllen has more than 40 years of experience as a medical surgical nurse, critical care nurse, nurse educator, unit manager, critical care director, and Vice President of Patient Care Services. Dr. McAllen received his Doctor of Nursing Practice from Waynesburg University in Waynesburg, PA; Master of Business Administration from Case Western Reserve University; Cleveland, OH; and his Bachelor of Science in Nursing from Kent State University, Kent, OH.

Kimberly Stephens, DNP, MSN, RN, DNP

Email: Kstephe@waynesburg.edu

Kimberly Stephens serves as an Assistant Professor of Nursing at Waynesburg University and is the Co-Director of the DNP program.

Brenda Swanson-Biearman, DNP, MPH, RN

Email: bswanson@waynesburg.edu

Brenda Swanson-Biearman holds a BSN from Carlow University, an MPH (Epidemiology) from the University of Pittsburgh as an NIH training fellow, and a DNP from Waynesburg University. She is an assistant professor, and director of simulation and research in the Department of Physician Assistant Studies at Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, PA. She has over twenty years of clinical experience in pediatric endocrinology, critical care, and toxicology. Dr. Swanson-Biearman has been an educator for 17 years in both nursing and physician assistant education.

Kimberly Kerr, MSN, RN

Email: KerrK@ccf.org

Kimberly Kerr is the Director of Nursing Professional Practice, Development & Research at Cleveland Clinic Akron General. She obtained a diploma in nursing from Massillon City Hospital School of Nursing; a Bachelor of Science in Nursing from Central Methodist College; and a Masters of Science in Nursing in Community Mental Health Administration from The University of Missouri. She holds Nurse Executive Advanced, Nursing Professional Development, and Rehabilitation Registered Nurse certifications.

Kimberly Whiteman, DNP, MSN, RN, CCRN-K

Email: Kwhitema@waynesburg.edu

Kimberly Whiteman is an Assistant Professor of Nursing and Co-Director of the DNP Program at Waynesburg University, Waynesburg, PA.

References

AHRQ. (2013). Preventing falls in hospitals. Retrieved from https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/systems/hospital/fallpxtoolkit/fallpxtk5.html

Cairns, L.L., Dudjak, L.A., Hoffman, R.L., & Lorenz, H.L. (2013). Utilizing bedside shift report to improve the effectiveness of shift handoff. Journal of Nursing Administration, 43(3), 160-165. doi:10.1097/NNA.0b013e318283dc02

Evans, D., Grunawalt, J., McClish, D., Wood, W., & Friese, C. R. (2012). Bedside shift-to-shift nursing report: Implementation and outcomes. MEDSURG Nursing, 21(5), 281-292.

Force, M.V., Deering, L., Hubbe, J., Anderson, M., Hagemann, B., Cooper-Hahn, M., & Peters, W. (2006). Effective strategies to increase reporting of medication errors in hospitals. Journal of Nursing Administration, 36(1), 34-41.

HCAHPS, Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems. (2015). Survey instruments. Retrieved from http://www.hcahpsonline.org/surveyinstrument.aspx

Heinricks, W., Bauman, B., & Dev, P. (2102). SBAR ‘flattens the hierarchy’ among caregivers. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 173, 175-182. doi:10.3233/978-1-61499-022-2-175

Institute of Medicine. (2001). Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Jeffs, L., Alcott, A., Simpson, E., Campbell, H., Irwin, T., Lo, J., Beswick, S., & Cardoso, R. (2013). The value of bedside shift reporting. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 28(3),226-232. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0b013e3182852f46

Kotter, J. (1996). Leading change. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press.

Laws, D. & Amato, S. (2010). Incorporating bedside reporting into change-of-shift report. Rehabilitation Nursing, 35(2),70-74.

Mayo, A., & Duncan, D., (2004). Nurse perceptions of medication errors. What we need to know for patient safety. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 19(3), 209-217.

Medicare.gov. (n.d.). Hospital value-based purchasing. Retrieved from https://www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare/Data/hospital-vbp.html

Maxson, P., Derby, K., Wrobleski, D., Foss, D. (2012). Bedside nurse-to-nurse handoff promotes patient safety. MEDSURG Nursing, 21(3), 140-144.

Mayer, T., & Cates, R., (2014). Leadership for great customer service. Chicago, IL: Health Administration Press.

Press Ganey® Survey. (2015). Retrieved from: http://www.pressganey.com/client-login

Sand-Jecklin, K. & Sherman, J. (2013). Incorporating bedside report into nursing handoff. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 28(2), 186-194. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0b013e31827a4795

Sand-Jecklin, K. & Sherman, J. (2014). A quantitative assessment of patient and nurse outcomes of bedside report implementation. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 23(19/20), 2854-2863. doi: 10.1111/jocn12575

Swanson, K. (1993). Nursing as an informal caring for the well-being of others. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 25(4), 352-354.

Taylor, M.J., McNicholas, C., Nicolay, C., Darzi, A., Bell, D., & Reed, J.E. (2013). Systematic review of the application of the plan-do-study-act method to improve quality in healthcare. British Medical Journal Quality & Safety, doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2013-001862

The Deming Institute. (n.d.)The plan, do, study, act (pdsa) cycle. Retrieved from https://deming.org/explore/p-d-s-a

Titler, M. (2011). Iowa model of evidence-based practice. In J. Rycroft-Malone & T. Bucknall (Eds.). Models and Frameworks for Implementing Evidence-Based Practice: Linking Evidence to Action (pp. 137-144). Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell.

Watson, J. (1999). Post modern nursing and beyond. Edinburg: Churchill Livingstone.