Emerging infectious diseases impact healthcare providers in the United States and globally. Nurses play a vital role in protecting the health of patients, visitors, and fellow staff members during routine practice and biological disasters, such as bioterrorism, pandemics, or outbreaks of emerging infectious diseases. One vital nursing practice is proper infection prevention procedures. Failure to practice correctly and consistently can result in occupational exposures or disease transmission. This article reviews occupational health risks, and pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions for nurses who provide care to patients with new or re-emerging infectious diseases. Infection prevention education based on existing infection prevention competencies is critical to ensure adequate knowledge and safe practice both every day and in times of limited resources. Challenges specific to infectious disease disasters are discussed, as well as the role of microorganisms and nurse education for infection prevention.

Key Words: infection prevention; healthcare associated infection; emerging infectious disease; bioterrorism; personal protective equipment; respirator; hand hygiene; mask; competency; training; education; global health; nurse; disaster; Ebola; Zika; SARS Co-V; MERS Co-V

Nurses play a vital role to protect the health of patients, visitors, and fellow staff members during routine practice and biological disasters... New or re-emerging infectious diseases contribute to, but are not the sole cause of, infectious disease morbidity and mortality worldwide. In the United States (U.S.) and globally, infectious diseases are the third leading cause of death (Heron, 2016). Nurses play a vital role to protect the health of patients, visitors, and fellow staff members during routine practice and biological disasters, such as bioterrorism, pandemics, or outbreaks of emerging infectious diseases. Failure to implement correct infection prevention practices can result in healthcare-associated disease transmission and occupational exposure for healthcare personnel, and can impact the health of communities.

Impact of New or Emerging Infectious Diseases

Multiple new diseases have been identified... [and] multiple existing infectious diseases have re-emerged or resurged, causing large outbreaks. New or re-emerging infectious diseases can have a huge impact on morbidity, mortality, and costs to the affected region, and pose a significant challenge to healthcare and public health systems. Multiple new diseases have been identified during the past twenty years, including severe acute respiratory syndrome corona-virus (SARS Co-V), Middle East respiratory syndrome corona-virus (MERS Co-V), and novel strains of avian and swine influenza. In addition, multiple existing infectious diseases have re-emerged or resurged, causing large outbreaks. Two recent examples include Zika and Ebola. The Zika virus has caused disease in more than 28 countries and is associated with severe birth defects, such as microcephaly (Cauchemez et al., 2016). The 2014 Ebola virus outbreak infected almost 30,000 individuals and resulted in more than 11,000 deaths worldwide (CDC, 2016a).

Healthcare providers have increasingly been challenged by the increase in multi-drug resistant organisms (MDRO), in particular antibiotic-resistant bacteria; at least 2 million are infected and 23,000 die each year in the States United States from MDROs (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2013). Individuals infected with MDROs are more likely to die from their infection than those infected with a pathogen that is not drug resistant (CDC, 2013). Healthcare-associated infections (HAI) due to more common pathogens, such as Staphylococcus, also contribute to routine infectious disease morbidity and mortality. Approximately 722,000 individuals are infected and 75,000 will die from an HAI each year in U.S. hospitals (CDC, 2016b).

In addition to the ongoing risk of an outbreak from a new or emerging infectious disease, and the challenges posed by commonly encountered infectious diseases, there is also the perpetual risk of intentional use of a biological agent in the form of a bioterrorism attack. Bioterrorism poses unique challenges to healthcare providers and public health, because the pathogens are rare, they often lack a vaccine or efficacious anti-infective therapy, and a covert attack would be very difficult to detect (Rebmann, 2014).

Outbreaks of SARS Co-V, MERS Co-V, and Ebola have all involved extensive spread in hospitals, both within the United States and globally. Single cases of a new or emerging disease, or an infectious disease outbreak, whether naturally occurring or man-made, challenge healthcare providers and public health systems. Disease transmission can occur within the community, and settings in which young children or elderly persons congregate are most likely to be involved. For example, childcare agencies (de Perio, Wiegand, & Evans, 2012), schools (Chao, 2010), and long-term care facilities (Murray et al., 2016) are likely sites for infectious disease transmission during routine times as well as during outbreaks. Disease transmission can also occur in any setting where healthcare is delivered, especially in hospitals where high consequence opportunities exist including use of invasive devices and therapeutic interventions. Outbreaks of SARS Co-V (Webb, Blaser, Zhu, Ardal, & Wu, 2004), MERS Co-V (Park et al., 2016), and Ebola (Dunn et al., 2016) have all involved extensive spread in hospitals, both within the United States and globally.

One important aspect of nursing practice is the proper use of infection prevention procedures. Infection prevention practices can limit disease transmission and occupational exposures when implemented consistently and correctly. However, researchers have found that many healthcare personnel do not consistently implement infection prevention measures correctly (Assiri et al., 2013; Rebmann, Carrico, & Wang, 2013; Shigayeva et al., 2007). This article reviews the role of infection prevention when nurses provide care to patients with new or re-emerging infectious diseases as a means of limiting healthcare-associated disease transmission and preventing occupational exposure.

Occupational Health Risk for Nurses

Healthcare personnel had significantly higher risk of infection than non-healthcare individuals during the 2014 Ebola outbreak and 2003 SARS Co-V outbreak. Nurses are at risk of occupational exposure to life-threatening infectious diseases when providing care to individuals infected with new or emerging pathogens. Healthcare personnel had significantly higher risk of infection than non-healthcare individuals during the 2014 Ebola outbreak (Evans, Goldstein, & Popova, 2015) and 2003 SARS Co-V (Health Canada, 2003) outbreak. For example, in Sierra Leone, Africa, the Ebola infection rate was 103-fold higher among healthcare personnel compared to non-healthcare workers (Kilmarx et al., 2014). Two of the four U.S. Ebola-infected cases were healthcare personnel who were exposed while providing care to an imported case (CDC, 2014a). In Canada, approximately half of all SARS Co-V cases consisted of healthcare personnel who had been exposed through patient care activities (Webb et al., 2004). Healthcare workers have also been found to be at high risk of infection from MERS, especially during healthcare-based outbreaks (Chung-Jong Kim, In press).

Pharmacological Intervention Availability and Efficacy

Pharmacological interventions (e.g., anti-infective therapy, chemoprophylaxis, and vaccination) are likely of varying and potentially limited use during a bioterrorism attack, outbreak of a new or emerging pathogen, or a pandemic. Of these, chemoprophylaxis is most likely to aid in minimizing morbidity and mortality for bioterrorism or a pandemic. Efficacious regimens have been identified for use as post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) or pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for many potential bioterrorism agents and could be used during an influenza pandemic (Rebmann, 2014).

However, new or emerging infectious diseases are significantly less likely to have a known efficacious chemoprophylaxis identified... However, new or emerging infectious diseases are significantly less likely to have a known efficacious chemoprophylaxis identified; there is little to no research regarding the effectiveness of existing antibiotics or anti-virals against emerging pathogens. For example, there is currently no known prophylaxis for Ebola, Zika, SARS CoV, or MERS CoV. In addition, though effective PEP and PrEP have been identified for some infectious diseases, researchers have reported that the United States lacks sufficient stockpiles of medication to provide mass PEP or PrEP (Rebmann, Wilson, LaPointe, Russell, & Moroz, 2009; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [U.S. DHHS], 2013).

Vaccination is one of the most effective infection prevention interventions and is critical to limit disease transmission and protect nurses from illness during routine times. Current CDC guidelines list vaccines relevant for healthcare personnel as a means of protecting the worker from illness and preventing transmission from the healthcare professional to patients and others (Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2011). These recommendations stress the need for immunization against hepatitis B, measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella as well as a one-time dose of Tdap [tetanus, diphtheria, pertussis), and an annual influenza immunization. Additional vaccines are also recommended for healthcare personnel who have special circumstances with respect to work responsibilities and exposure risk, such as provision of meningococcal vaccine for laboratory personnel who may be routinely exposure to Neisseria meningitidis during specimen handling or processing.

During a bioterrorism attack, outbreak of a new or emerging pathogen, or a pandemic, vaccination may have a limited role. During a bioterrorism attack, outbreak of a new or emerging pathogen, or a pandemic, vaccination may have a limited role. Many potential bioterrorism agents do not have a vaccine; the vaccine is only Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for laboratory personnel (e.g., tularemia); or it is not FDA-approved for PEP use (i.e., anthrax) (Rebmann, 2014). None of the most severe or deadly emerging infectious diseases, including SARS Co-V, MERS CoV, or Zika, currently have an effective vaccine. However, vaccine may be available during a future pandemic, depending upon the influenza strain that emerges. Various pre-pandemic vaccines have been created, but may provide limited protection depending upon cross-reactivity to the circulating pandemic strain (Rebmann & Zelicoff, 2012).

Seven to ten month delays in vaccine release have been experienced during past pandemics (Lagace-Wiens, Rubinstein, & Gumel, 2010). If a completely novel influenza strain emerged into a pandemic, there would be need to develop a new vaccine. Such a vaccine would be expected to have a delayed and staggered release that will leave many nurses at risk from infection until six or more months after the novel strain is identified (Haaheim, Madhun, & Cox, 2009; Rebmann & Zelicoff, 2012).

... it will be critical that nurses follow the PEP or PrEP regimen correctly and/or receive the event-specific vaccine to protect themselves from disease. If pharmacological interventions are available during a bioterrorism attack, outbreak of an emerging infectious disease, or a pandemic, nurses could protect their patients, their families, and themselves if they take or receive the medication/vaccine as recommended. Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) or pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) could involve taking anti-virals for up to six weeks at a time (U.S. DHHS, 2013) and vaccine could be released off-label or under an emergency authorization usage format, meaning non-FDA-approved (Rebmann & Zelicoff, 2012). Despite this, it will be critical that nurses follow the PEP or PrEP regimen correctly and/or receive the event-specific vaccine to protect themselves from disease (U.S. DHHS, 2013). Of concern, this did not occur during the 2009 pandemic, during which healthcare personnel had very poor uptake of the H1N1 vaccine (Rebmann, Wright, Anthony, Knaup, & Peters, 2012; Rebmann & Zelicoff, 2012), and low compliance may have contributed to morbidity and mortality among patients.

Non-Pharmacological Interventions to Manage Potentially Contagious Patients

Non-pharmacological interventions (NPI) are more likely than pharmacological interventions to be available and useful during an outbreak... In addition to pharmacological interventions during a bioterrorism attack, outbreak of an emerging infectious disease, or a pandemic, nurses should implement protective measures that do not involve a pharmaceutical product to limit disease spread. Non-pharmacological interventions (NPI) are more likely than pharmacological interventions to be available and useful during an outbreak of an emerging infectious disease, pandemic, or bioterrorism attack (Rebmann, 2014).

NPIs include surveillance; standard precautions and isolation; use of personal protective equipment (PPE); hand hygiene; quarantine; environmental disinfection; and social distancing. Studies have indicated that NPIs can minimize morbidity and mortality when implemented correctly and consistently (Bell, 2006a; 2006b). Nurses should be familiar with the NPIs most appropriate to their scope of practice during a biological event; namely, surveillance, standard precautions and isolation, PPE usage, and hand hygiene. This section will discuss these in more detail below.

Surveillance

During the SARS Co-V outbreak in Canada, it was estimated that 10 healthcare workers were infected for every day that a symptomatic, infected individual was not placed in isolation. Identifying individuals who are potentially contagious, or surveillance, is a vital nursing practice. When contagious individuals are not identified, they are not placed in isolation and this omission can lead to disease transmission between patients within healthcare facilities (Banach, Bielang, & Calfee, 2011). During outbreaks of emerging infectious diseases, failure to correctly identify contagious individuals can affect not only other patients, but healthcare personnel as well. During the SARS Co-V outbreak in Canada, it was estimated that 10 healthcare workers were infected for every day that a symptomatic, infected individual was not placed in isolation (Health Canada, 2003). An epidemiological study conducted over three months in a single hospital emergency department during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic found that there were 179 unprotected staff exposures due to failure to identify and isolate symptomatic patients (Banach et al., 2011).

Theoretically, these staff exposures and illnesses could have been prevented if healthcare personnel had correctly identified contagious patients and isolated them quickly and appropriately. Failure to identify contagious patients was also associated with healthcare personnel infections during the Ebola outbreak (Kilmarx et al., 2014).

Standard Precautions and Isolation

One basic tenet of infection prevention is the use of standard and transmission-based precautions (i.e., isolation) both in inpatient and outpatient settings (Siegel, Rhinehart, Jackson, Chiarello, & Health Care Infection Control Practices Advisory, 2007). In addition to providing guidelines for isolating potentially contagious individuals, the 2007 CDC isolation guidelines address respiratory hygiene practices; the challenges of managing patients infected with emerging pathogens; multidrug-resistant organisms; environmental controls; and safe injection practices (Siegel et al., 2007). The revised guidelines also emphasize the importance of isolating individuals suspected of having a contagious illness/condition rather than waiting for laboratory confirmation for disease presence (Siegel et al., 2007).

...researchers have found that healthcare personnel often demonstrate low compliance with standard and transmission-based precautions. Despite the widespread dissemination of these guidelines and incorporation into healthcare policies and procedures, researchers have found that healthcare personnel often demonstrate low compliance with standard and transmission-based precautions. For example, only 16% of nurses from a community hospital reported that they always follow contact precautions correctly (Jessee & Mion, 2013). Observation studies have found only 22% of healthcare personnel were compliant with respiratory hygiene and 60-75% with isolation precautions (Manian, 2007; Martel et al., 2013; Weber et al., 2007).

Failure to identify potentially contagious individuals is a common cause of non-compliance with isolation (Banach et al., 2011; Health Canada, 2003; Kilmarx et al., 2014). However, incorrect use of PPE and failure to perform hand hygiene are other forms of isolation non-compliance that lead to disease transmission and occupational exposure (Bledsoe et al., 2014; Casalino et al., 2015). Self-reported and observed behaviors have been found to differ significantly in terms of compliance with isolation practices; studies have found that self-reported compliance is high while actual observed practice demonstrates low compliance (Jessee & Mion, 2013; Martel et al., 2013). For this reason, researchers recommend that isolation compliance be monitored via direct observation, though this can be resource-intensive (Ross et al., 2011).

Personal Protective Equipment

Improper use of PPE can result in auto-inoculation during use or removal, which can lead to infection. A critical component of standard and transmission-based precautions is the use of PPE. Recommendations regarding correct selection and use of PPE are outlined in the 2007 CDC isolation guidelines (Siegel et al., 2007). Multiple types of PPE are available for use in healthcare settings, including non-sterile and sterile gloves; impervious and non-impervious gowns; masks; and eye protection. Higher levels of respiratory protection, such as respirators, are also included as PPE (Siegel et al., 2007). Various professional organizations, associations, and governmental agencies have outlined procedures for donning and doffing PPE using multiple types of training materials that include graphics, photos, step-by-step written instructions, and multimedia videos. The CDC has developed extensive educational programs related to PPE use specific to Ebola due to recommendations to use additional items not regularly used for isolation precautions, such as boots, impervious gowns, aprons, full body suits, and hoods (CDC, 2015).

Despite these tools and resources, compliance with PPE has been found lacking among healthcare personnel and these lapses have been associated with occupational exposures and illness (Kilmarx et al., 2014). Researchers have found that fewer than 15% of healthcare personnel were able to correctly don and doff PPE needed to provide care for Ebola patients (Beam, Gibbs, Boulter, Beckerdite, & Smith, 2011). Studies examining glove use have found that about 60% of healthcare personnel wore gloves when the task required it (Bledsoe et al., 2014; Hitoto et al., 2009). An observation study examining compliance with contact isolation found that only 76% of healthcare personnel donned a gown for each patient encounter (Manian, 2007).

...even after three training sessions, half of all medical and nursing students made critical errors when removing PPE. Even education interventions have not supported compliance close to 100%. One study found that PPE compliance improved from 44% to only 69% after an education intervention (Allen & Cronin, 2012). Casalino et al. (2015) reported that, even after three training sessions, half of all medical and nursing students made critical errors when removing PPE. One possible reason why most past training interventions have not resulted in positive long-term outcomes is that they have not been competency-based programs, or only utilized verbal education versus incorporating simulation, role playing, or the use of standardized patients. A more recent study found no self-contamination of skin or clothing after healthcare personnel were provided CDC-standardized Ebola PPE education coupled with simulation (Casanova et al., 2016). Additional studies need to examine the impact of other competency-based curricula on PPE compliance.

Improper use of PPE can result in auto-inoculation during use or removal, which can lead to infection. Healthcare personnel who did not wear PPE consistently or correctly were found at significantly higher risk of MERS Co-V infection, compared to healthcare workers who had better PPE compliance (Chung-Jong Kim, In press). Researchers reported similar findings during the 2003 SARS Co-V outbreak. Approximately half of all individuals infected with SARS Co-V in Canada were healthcare personnel infected through occupational exposures, most believed to be related to improper removal of respirators (Health Canada, 2003; Moore, Gamage, Bryce, Copes, & Yassi, 2005). Improper use of PPE was also associated with Ebola infection among healthcare personnel (Kilmarx et al., 2014).

Hand Hygiene

Performance of patient care with clean hands has been a foundational element in nursing care since the birth of the profession. Performance of patient care with clean hands has been a foundational element in nursing care since the birth of the profession. Guidelines outlining when, how, and under what circumstances to perform a soap and water hand wash versus an alcohol-based hand rub have been published by the CDC (Boyce & Pittet, 2002). Monitoring hand hygiene to track compliance rates has been a common occurrence in healthcare settings and has involved multiple healthcare disciplines.

Hand hygiene is critical to the prevention of infection transmission. However, rates of compliance with hand hygiene guidelines remain low. For example, a study of emergency medical services personnel found that 28% of staff performed hand hygiene when indicated (Bledsoe et al., 2014). Hand hygiene compliance was found to be between 40–53% among triage nurses in an emergency department (Martel et al., 2013). Healthcare agencies should continue to educate healthcare personnel regarding proper hand hygiene, monitor compliance, and intervene when incorrect practice is identified.

Challenges Specific to Infectious Disease Disasters

Infectious disease disasters... pose unique challenges to following stringent infection prevention. Implementing infection prevention practices correctly and consistently is difficult even during routine times. Infectious disease disasters (e.g., bioterrorism, outbreaks of an emerging infectious disease, and pandemics) pose unique challenges to following stringent infection prevention. These events are often associated with an influx of potentially contagious individuals, resulting in healthcare surge and a shortage of medical supplies, including hand hygiene products and PPE, and isolation areas (Kilmarx et al., 2014; Rebmann, 2014). Several of these challenges are discussed briefly below, including shortages of PPE, staffing challenges, and changing recommendations.

Insufficient PPE

During the 2014 Ebola outbreak, PPE availability was severely limited, leading to potential occupational exposures and healthcare personnel infection.Shortages of PPE put nurses at risk of exposure and infection. Multiple studies have found that U.S. hospitals and healthcare agencies lack sufficient PPE and even stockpiles have not provided adequate or correct supplies to give healthcare personnel necessary PPE during past events (Lautenbach, Saint, Henderson, & Harris, 2010; Rebmann & Wagner, 2009). During the 2014 Ebola outbreak, PPE availability was severely limited, leading to potential occupational exposures and healthcare personnel infection (Kilmarx et al., 2014). When respirators are limited, remaining supplies can be worn for extended periods of time or re-used between patients (Rebmann et al., 2013). However, extending the use or re-using respirators puts nurses at risk of exposure due to auto-inoculation when removing contaminated equipment or from reduced compliance during long-term wear (Rebmann et al., 2013; Seale, Corbett, Dwyer, & MacIntyre, 2009).

Staffing Shortages

Staff shortages can limit the availability of infection preventionists... Staffing shortages during infectious disease disasters may leave nurses at risk of occupational exposure due to exhaustion and insufficient infection prevention measures (Kilmarx et al., 2014). Staff shortages can limit the availability of infection preventionists to assist with training and PPE compliance checks, which can result in exposures and illness (Pathmanathan et al., 2014). During the Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone, staffing shortages were common and believed to be associated with the high rate of infection among healthcare personnel (Kilmarx et al., 2014).

Changing Recommendations

...recommended control measures may change mid-event. Another challenge to following infection prevention practices during an infectious disease disaster is that recommended control measures may change mid-event. This is especially true during outbreaks of a new or emerging infectious disease, when limited information about the causative agent is available. As clinical and epidemiological data is obtained on the new or emerging disease, PPE or isolation recommendations may be altered (Rebmann & Wagner, 2009).

Changing infection prevention recommendations occurred during the 2003 SARS outbreak (Rebmann, 2014), the 2009 H1N1 pandemic (Rebmann & Wagner, 2009), and the 2014 Ebola outbreak (CDC, 2014b), and is likely to occur in future events. It is common for the CDC to take a conservative approach to recommended PPE and isolation when a new or emerging infectious disease occurs and there are limited data about the disease transmission route (Rebmann, 2014). For example, the CDC recommends use of airborne isolation and N95 respirators when providing care to patients infected with SARS Co-V or MERS Co-V, though transmission likely occurs primarily through respiratory droplets rather than airborne droplet nuclei. The CDC also updated PPE recommendations for healthcare personnel providing care to patients during the 2014 Ebola outbreak (CDC, 2015). Nurses should expect changing recommendations during outbreaks of new or emerging infectious diseases, in an ongoing effort to limit or prevent occupational exposures.

... the foundational tenets of infection prevention practices are the basis of routine care and the starting point for care during emerging infectious diseases. In sum, measures to prevent infection are challenging during stable times, and more challenging during critical outbreaks. However, the foundational tenets of infection prevention practices are the basis of routine care and the starting point for care during emerging infectious diseases. The lack of knowledge and compliance in the area of infectious disease prevention practices is of concern. The following section briefly summarizes the role of microorganisms in disease transmission and discusses infection prevention competencies and training appropriate for nurses in everyday practice and during times of emerging infectious diseases in the United States and/or globally.

Role of Microorganisms in Disease Transmission

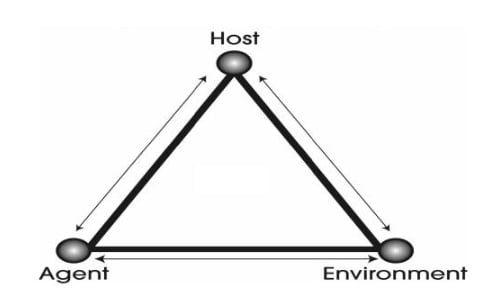

Nurses must understand the epidemiological triangle, as this informs the basis for competent practice... An essential component of infection prevention is basic knowledge regarding the role microorganisms play in disease transmission. Nurses must understand that infection or colonization in a patient or healthcare worker enables disease transmission, because it means that an infectious agent is present. If an infectious agent interacts with a susceptible host (e.g., an unimmunized healthcare worker) within an environment that enables transmission, an infection can occur; this is known as the epidemiological triangle (CDC, 2011). This model emphasizes the critical need for nurses to have a working knowledge of the types of microorganisms (e.g., bacteria, virus) in transmission methods that cause disease so appropriate interventions can be implemented. Nurses must understand the epidemiological triangle (pictured in the figure below), as this informs the basis for competent practice, regardless of whether it is a commonly encountered infectious disease or an emerging pathogen.

Figure. Epidemiological Triangle

Infection Prevention Competencies for Nurses

Professional competencies are a method to articulate knowledge and skills that individuals need to perform successfully in a given field. One of the earliest sets of nursing and infectious disease competencies focused on public health preparedness (Gebbie & Qureshi, 2002); they have been accepted as a cornerstone for safe practice in public health. Best practices related to infection prevention have been outlined in numerous CDC guidelines and related regulatory requirements and standards regarding care provided in healthcare settings.

Lack of a clear national document regarding basic infection prevention practices applicable for healthcare workers in all settings where care is delivered is a recognized gap. Guidelines provide information on what should occur, but do not include how nurses should apply the information. Recommendations regarding infection prevention competencies for hospital-based healthcare workers in the United States was first proposed in 2008 (Carrico, Rebmann, English, Mackey, & Cronin, 2008) and for healthcare workers in Canada in 2006 (Henderson, 2006). A summary of the proposed competencies is found in the Table. Lack of a clear national document regarding basic infection prevention practices applicable for healthcare workers in all settings where care is delivered is a recognized gap. This gap has been discussed at the national level, and the CDC (2014c) is currently developing guidelines to provide a set of broadly applicable practices that lead to widespread acceptance and implementation.

Table. Infection Prevention Competencies for Nurses

|

Competency 1: Basic Microbiology Describe the role of microorganisms in disease.

|

|

Competency 2: Modes/Mechanisms of Infection/Disease Transmission Describe how microorganisms are transmitted in healthcare settings.

|

|

Competency 3: Standard and Transmission-Based Precautions Demonstrate standard and transmission-based precautions for all patient contact in healthcare settings.

|

|

Competency 4: Occupational Health Describe occupational health practices that protect the healthcare worker from acquiring infection.

|

|

Competency 5: Patient Safety Describe practices that prevent the healthcare worker from transmitting infection to a patient.

|

|

Competency 6: Critical Thinking Demonstrate ability to problem-solve and apply knowledge to recognize, contain, and prevent infection transmission

|

|

Competency 7: Emergency Preparedness Describe the importance of healthcare preparedness for natural or man-made infectious disease disasters

|

Adapted from Carrico et al., 2008.

Nurse Education Related to Infection Prevention

Existing infection prevention competencies [include] the need for nurses to be aware of altered standards of care in situations that involve limited resources. Education for nurses related to infection prevention is critical to ensure adequate knowledge and safe practice (Casalino et al., 2015). Existing infection prevention competencies, such as those in the Table above, should be used as the basis for this training, including the need for nurses to be aware of altered standards of care in situations that involve limited resources (Carrico et al., 2008). Applying this competency to local or global emerging infectious diseases means that nurses must be aware of the proper way to extend the use or re-use respiratory protection during biological disasters that result in an influx of contagious patients and depletion of PPE (Rebmann et al., 2013). It also requires providing nurses with event- or disease-specific education if the CDC recommends PPE beyond what is used during routine practice. An example of this is the use of full PPE (i.e., boots, impermeable apron) for patients infected with Ebola (Casalino et al., 2015).

One critical aspect of infection prevention training is that nurses demonstrate their competence (Carrico et al., 2008). This demonstration must extend beyond written or verbal mastery of the information and include physical demonstration of proper infection prevention practices. Researchers have found that nurses often have high knowledge of correct infection prevention protocols, yet their behaviors demonstrate low compliance (Jessee & Mion, 2013).

...including an observer who speaks aloud the PPE donning and doffing process steps as part of the training process results in significantly better performance. This knowledge-compliance gap is one reason why the CDC recommends incorporating trained observers into the donning and doffing process for healthcare personnel providing care for Ebola patients. Observers can identify and immediately stop errors that could lead to auto-inoculation (Cummings et al., 2016). In addition, researchers have found that including an observer who speaks aloud the PPE donning and doffing process steps as part of the training process results in significantly better performance (Casalino et al., 2015). Although incorporating observers into the PPE donning and doffing process may not be feasible to provide routine nursing care, an investment in this quality check may be warranted during outbreaks of a new or emerging infectious disease to prevent occupational exposure or illness.

Conclusion

Proper infection prevention is essential for routine nursing practice, during disasters, and when providing care to individuals infected with a new or emerging infectious disease. Proper infection prevention is essential for routine nursing practice, during disasters, and when providing care to individuals infected with a new or emerging infectious disease. Lack of compliance with infection prevention can put nurses at risk for occupational exposure or contribute to healthcare-associated disease transmission. Many nurses are not consistently compliant with infection prevention procedures, including lapses in personal protective equipment usage.

Better education about infection prevention that involves demonstration of proper performance is essential to ensure adequate knowledge and safe practice. Existing infection prevention competencies should be the basis for nurse training. Nurses should receive education about routine procedures as the basis for all care, and disease- or event-specific recommendations that includes information about altered standards of care in situations that involve limited resources.

Authors

Terri Rebmann, PhD, RN, CIC, FAPIC

Email: rebmannt@slu.edu

Terri Rebmann is a Professor and the Director of the Institute for Biosecurity in the Department of Epidemiology at the Saint Louis University College for Public Health & Social Justice. She attended Truman State University, where she earned her Bachelor’s of Science in Nursing. She earned an MSN at the University of Missouri, Columbia, focusing on adult infectious diseases with an emphasis on HIV/AIDS. She earned a PhD in Nursing at Saint Louis University. Dr. Rebmann is board certified in Infection Prevention and Epidemiology (i.e., CIC) and a Fellow of the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC). In her current position with the Institute for Biosecurity as the Director, she is responsible for managing all aspects of the Institute’s MPH and PhD academic programs, teaching classes in the programs, and conducting research. Her research areas of focus include healthcare and public health professional disaster preparedness, long-term use of respiratory protection, and addressing barriers to vaccine uptake. She publishes and lectures on bioterrorism, pandemic planning, emerging infectious diseases, and infection prevention practices on a national basis.

Ruth Carrico, PhD, FNP-C, FSHEA, CIC

Email: ruth.carrico@louisville.edu

Ruth Carrico is an Associate Professor in the Division of Infectious at the University of Louisville School of Medicine and a board certified family nurse practitioner. Dr. Carrico has worked in the field of infection prevention and control for more than twenty-five years and is also board certified in infection prevention and control. Her research and clinical practice focus on disease prevention in all settings where care is delivered and involves public health and care of vulnerable populations. She has served on a number of national committees as part of policy development including the CDC Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC). Dr. Carrico has particular interests in leadership in the area of infection prevention and was selected as a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Executive Nurse Fellow. In 2015, her interests and leadership led to the founding of the University of Louisville Global Health Center where she currently serves as the associate founding director.

References

Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. (2011). Immunization of health-care personnel: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports, 60(RR-7), 1-45.

Allen, S., & Cronin, S. N. (2012). Improving staff compliance with isolation precautions through use of an educational intervention and behavioral contract. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing, 31(5), 290-294. doi:10.1097/DCC.0b013e31826199e8

Assiri, A., McGeer, A., Perl, T. M., Price, C. S., Al Rabeeah, A. A., Cummings, D. A., ... Team, K. M.-C. I. (2013). Hospital outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. New England Journal of Medicine, 369(5), 407-416. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1306742

Banach, D. B., Bielang, R., & Calfee, D. P. (2011). Factors associated with unprotected exposure to 2009 H1N1 influenza A among healthcare workers during the first wave of the pandemic. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 32(3), 293-295. doi:10.1086/658911

Beam, E. L., Gibbs, S. G., Boulter, K. C., Beckerdite, M. E., & Smith, P. W. (2011). A method for evaluating health care workers' personal protective equipment technique. American Journal of Infection Control, 39(5), 415-420. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2010.07.009

Bell, D. M. (2006a). Non-pharmaceutical interventions for pandemic influenza, international measures. Emerg Infect Dis, 12(1), 81-87.

Bell, D. M. (2006b). Non-pharmaceutical interventions for pandemic influenza, national and community measures. Emerg Infect Dis, 12(1), 88-94.

Bledsoe, B. E., Sweeney, R. J., Berkeley, R. P., Cole, K. T., Forred, W. J., & Johnson, L. D. (2014). EMS provider compliance with infection control recommendations is suboptimal. Prehospital Emergency Care, 18(2), 290-294. doi:10.3109/10903127.2013.851311

Boyce, J. M., & Pittet, D. (2002). Guideline for Hand Hygiene in Health-Care Settings: recommendations of the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee and the HICPAC/SHEA/APIC/IDSA Hand Hygiene Task Force. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 23(12 Suppl), S3-40. doi:10.1086/503164

Carrico, R. M., Rebmann, T., English, J. F., Mackey, J., & Cronin, S. N. (2008). Infection prevention and control competencies for hospital-based health care personnel. American Journal of Infection Control, 36(10), 691-701. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2008.05.017

Casalino, E., Astocondor, E., Sanchez, J. C., Diaz-Santana, D. E., Del Aguila, C., & Carrillo, J. P. (2015). Personal protective equipment for the Ebola virus disease: A comparison of 2 training programs. American Journal of Infection Control, 43(12), 1281-1287. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2015.07.007

Casanova, L. M., Teal, L. J., Sickbert-Bennett, E. E., Anderson, D. J., Sexton, D. J.,

Rutala, W. A., & Weber, D.J. (2016). Assessment of self-contamination during removal of personal protective equipment for Ebola patient care. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 37(10), 1156-1161. doi:10.1017/ice.2016.169

Cauchemez, S., Besnard, M., Bompard, P., Dub, T., Guillemette-Artur, P., Eyrolle-Guignot, D., … Mallet, H. (2016). Association between Zika virus and microcephaly in French Polynesia, 2013-15: a retrospective study. Lancet, 387(10033), 2125-2132. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00651-6

Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. (2011). Principles of epidemiology in public health practice. In Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (Ed.), An Introduction to Applied Epidemiology and Biostatistics. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. (2013). Antibiotic resistance threats in the U.S. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/features/AntibioticResistanceThreats/index.html

Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. (2014a). Cases of Ebola diagnosed in the United States. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/outbreaks/2014-west-africa/united-states-imported-case.html

Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. (2014b). CDC tightened guidance for U.S. healthcare workers on personal protective equipment for Ebola. Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2014/fs1020-ebola-personal-protective-equipment.html

Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. (2014c). Meeting minutes: Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hicpac/pdf/mm/HICPAC_April2014_Summary_With_Liaison_ReportsFINAL.pdf

Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. (2015). Guidance on personal protective equipment (PPE) to be used by healthcare workers during management of patients with confirmed Ebola or persons under investigation (PUIs) for Ebola who are clinically unstable or have bleeding, vomiting, or diarrhea in U.S. hospitals, including procedures for donning and doffing PPE. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/healthcare-us/ppe/guidance.html

Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. (2016a). 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa - Case counts. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/outbreaks/2014-west-africa/case-counts.html

Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. (2016b). National and state healthcare associated infections progress report. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hai/surveillance/progress-report/index.html

Chao, D., Halloran, ME, Longini, IM. (2010). School opening dates predict pandemic influenza A(H1N1) in the United States. Journal of Infectious Disease, 877-880.

Chung-Jong K., Choi, W. S. Jung, Y., Kiem, S., Seol, H. Y., Woo, H. J., ... Choi, .J. (In press). Surveillance of the MERS Coronavirus infection in healthcare workers after contact with confirmed MERS patients: Incidence and risk factors of MERS-CoV seropositivity. Clinical Microbiology and Infection.

Cummings, K. J., Choi, M. J., Esswein, E. J., de Perio, M. A., Harney, J. M., Chung, W. M., … Rollin, P.E. (2016). Addressing infection prevention and control in the first U.S. community hospital to care for patients with Ebola Virus Disease: Context for national recommendations and future strategies. Annals of Internal Medicine. doi:10.7326/M15-2944

de Perio, M. A., Wiegand, D. M., & Evans, S. M. (2012). Low influenza vaccination rates among child care workers in the United States: Assessing knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. Journal of Community Health, 37(2), 272-281. doi:10.1007/s10900-011-9478-z

Dunn, A. C., Walker, T. A., Redd, J., Sugerman, D., McFadden, J., Singh, T., … Kilmarx, P.H. (2016). Nosocomial transmission of Ebola virus disease on pediatric and maternity wards: Bombali and Tonkolili, Sierra Leone, 2014. American Journal of Infection Control, 44(3), 269-272. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2015.09.016

Evans, D. K., Goldstein, M., & Popova, A. (2015). Health-care worker mortality and the legacy of the Ebola epidemic. Lancet Global Health, 3(8), e439-440. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00065-0

Gebbie, K. M., & Qureshi, K. (2002). Emergency and disaster preparedness: Core competencies for nurses. American Journal of Nursing, 102(1), 46-51.

Haaheim, L. R., Madhun, A. S., & Cox, R. (2009). Pandemic influenza vaccines - the challenges. Viruses, 1(3), 1089-1109. doi:10.3390/v1031089

Health Canada. (2003). Building capacity and coordination: National Infectious Disease Surveillance, Outbreak Management and Emergency Response. In H. Canada (Ed.), SARS in Canada (pp. 1-29). Toronto, Canada: Health Canada.

Henderson, E. (2006). Infection prevention and control core competencies for healthcare workers: A consensus document. Canadian Journal of Infection Control, 21, 62-67.

Heron, M. (2016). Deaths: Leading causes. National Vital Statistics Report, 65(5). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr65/nvsr65_05.pdf

Hitoto, H., Kouatchet, A., Dube, L., Lemarie, C., Mercat, A., Joly-Guillou, M. L., & Eviellard, M. (2009). Factors affecting compliance with glove removal after contact with a patient or environment in four intensive care units. Journal of Hospital Infection, 71(2), 186-188. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2008.11.005

Jessee, M.A., & Mion, L.C. (2013). Is evidence guiding practice? Reported versus observed adherence to contact precautions: A pilot study. American Journal of Infection Control, 41(11), 965-970. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2013.05.005

Kilmarx, P. H., Clarke, K. R., Dietz, P. M., Hamel, M. J., Husain, F., McFadden, J. D., … Jambai, A. (2014). Ebola virus disease in health care workers--Sierra Leone, 2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports, 63(49), 1168-1171.

Lagace-Wiens, P. R., Rubinstein, E., & Gumel, A. (2010). Influenza epidemiology--past, present, and future. Critical Care Medicine, 38(4 Suppl), e1-9. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cbaf34

Lautenbach, E., Saint, S., Henderson, D. K., & Harris, A. D. (2010). Initial response of health care institutions to emergence of H1N1 influenza: Experiences, obstacles, and perceived future needs. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 50(4), 523-527. doi:10.1086/650169

Manian, F. A., and Ponzillo, J. J. (2007). Compliance with routine use of gowns by healthcare workers (HCWs) and non-HCW visitors on entry into the rooms of patients under contact precautions. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 28(3), 337-340.

Martel, J., Bui-Xuan, E. F., Carreau, A. M., Carrier, J. D., Larkin, E., Vlachos-Mayer, H., & Dumas, M. E. (2013). Respiratory hygiene in emergency departments: Compliance, beliefs, and perceptions. American Journal of Infection Control, 41(1), 14-18. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2011.12.019

Moore, D., Gamage, B., Bryce, E., Copes, R., & Yassi, A. (2005). Protecting health care workers from SARS and other respiratory pathogens: organizational and individual factors that affect adherence to infection control guidelines. American Journal of Infection Control, 33(2), 88-96. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2004.11.003

Murray, M. T., Jackson, O., Cohen, B., Hutcheon, G., Saiman, L., Larson, E., & Neu, N. (2016). Impact of infection prevention and control initiatives on acute respiratory infections in a pediatric long-term care facility. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 37(7), 859-862. doi:10.1017/ice.2016.73

Park, S. H., Kim, Y. S., Jung, Y., Choi, S. Y., Cho, N. H., Jeong, H. W., … Sohn, K.M. (2016). Outbreaks of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome in two hospitals initiated by a single patient in Daejeon, South Korea. Infection and Chemotherapy, 48(2), 99-107. doi:10.3947/ic.2016.48.2.99

Pathmanathan, I., O'Connor, K. A., Adams, M. L., Rao, C. Y., Kilmarx, P. H., Park, B. J., … Clarke, K.R. (2014). Rapid assessment of Ebola infection prevention and control needs--six districts, Sierra Leone, October 2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports, 63(49), 1172-1174. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6349a7.htm

Rebmann, T. (2014). Infectious disease disasters: Bioterrorism, emerging infections, and pandemics. In Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (Ed.), APIC Text of Infection Control & Epidemiology (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology.

Rebmann, T., Carrico, R., & Wang, J. (2013). Physiologic and other effects and compliance with long-term respirator use among medical intensive care unit nurses. American Journal of Infection Control, 41(12), 1218-1223. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2013.02.017

Rebmann, T., & Wagner, W. (2009). Infection preventionists' experience during the first months of the 2009 novel H1N1 influenza: A pandemic. American Journal of Infection Control, 37(10), e5-e16. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2009.09.003

Rebmann, T., Wilson, R., LaPointe, S., Russell, B., & Moroz, D. (2009). Hospital infectious disease emergency preparedness: A 2007 survey of infection control professionals. American Journal of Infection Control, 37(1), 1-8. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2008.02.007

Rebmann, T., Wright, K. S., Anthony, J., Knaup, R. C., & Peters, E. B. (2012). Seasonal influenza vaccine compliance among hospital-based and nonhospital-based healthcare workers. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 33(3), 243-249. doi:10.1086/664057

Rebmann, T., & Zelicoff, A. (2012). Vaccination against influenza: Role and limitations in pandemic intervention plans. Expert Review of Vaccines, 11(8), 1009-1019. doi:10.1586/erv.12.63

Ross, B., Marine, M., Chou, M., Cohen, B., Chaudhry, R., Larson, E., … Behta, M. (2011). Measuring compliance with transmission-based isolation precautions: comparison of paper-based and electronic data collection. American Journal of Infection Control, 39(10), 839-843. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2011.01.020

Seale, H., Corbett, S., Dwyer, D. E., & MacIntyre, C. R. (2009). Feasibility exercise to evaluate the use of particulate respirators by emergency department staff during the 2007 influenza season. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 30(7), 710-712. doi:10.1086/599254

Shigayeva, A., Green, K., Raboud, J. M., Henry, B., Simor, A. E., Vearncombe, M., … McGeer, A. (2007). Factors associated with critical-care healthcare workers' adherence to recommended barrier precautions during the Toronto severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 28(11), 1275-1283. doi:10.1086/521661

Siegel, J. D., Rhinehart, E., Jackson, M., Chiarello, L., & Health Care Infection Control Practices Advisory, C. (2007). 2007 Guideline for isolation precautions: Preventing transmission of infectious agents in health care settings. American Journal of Infection Control, 35(10 Suppl 2), S65-164. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2007.10.007

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2013). Considerations for antiviral drug stockpiling by employers in preparation for an influenza pandemic. Retrieved from https://www.hsdl.org/?view&did=233067

Webb, G. F., Blaser, M. J., Zhu, H., Ardal, S., & Wu, J. (2004). Critical role of nosocomial transmission in the toronto sars outbreak. Math and Bioscience Engineering, 1(1), 1-13.

Weber, D. J., Sickbert-Bennett, E. E., Brown, V. M., Brooks, R. H., Kittrell, I. P., Featherstone, B. J., … Rutala, V.A. (2007). Compliance with isolation precautions at a university hospital. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 28(3), 358-361. doi:10.1086/510871