People with disabilities use various assistance devices to improve their capacity to lead independent and fulfilling lives. Service dogs can be crucial lifesaving companions for their owners. As the use of service dogs increases, nurses are more likely to encounter them in healthcare settings. Service dogs are often confused with therapy or emotional support dogs. While some of their roles overlap, service dogs have distinct protection under the American Disabilities Act (ADA). Knowing the laws and proper procedures regarding service dogs strengthens the abilities of healthcare providers to deliver holistic, patient-centered care. This article provides background information about use of dogs, and discusses benefits to patients and access challenges for providers. The author reviews ADA laws applicable to service dog use and potential challenges and risks in acute care settings. The role of the healthcare professional is illustrated with an exemplar, along with recommendations for future research and nursing implications related to care of patients with service dogs.

Key Words: Service dog, Medical Alert dog, disabled person, disability, assistance dog, Americans with Disabilities Act, ADA, therapy dog, ADA accommodations, ADA laws

With advancing technology, patients utilize many different medical devices. In order to provide complete, holistic, and patient-centered care, it is important to have a working knowledge about such devices and how they assist the patient. There is little information available for healthcare providers (HCP) about the roles of service dogs and professionals in caring for patients who use service dogs (Fairman & Huebner, 2000). Holistic care is difficult to achieve when a patient’s service dog is disregarded as a non-essential member of the patient healthcare team; however, service dogs are often excluded from the patient plan of care (Fairman & Huebner, 2000). In many cases, separating service dogs from patients in acute care settings is counterproductive to health and well-being.

The use of service dogs has risen considerably. The use of service dogs has risen considerably (Duncan, 2000). As their use continues to increase, nurses will encounter more service dogs when caring for patients. Improving education for healthcare providers about the use of service dogs will build trust and provide better care for patients who rely on service dogs to keep them safe and assist in maintaining health.

This article provides background information about use of dogs, and discusses benefits to patients and access challenges for providers. The author reviews ADA laws applicable to service dog use and potential challenges and risks in acute care settings. The role of the healthcare professional is illustrated with an exemplar, along with recommendations for future research and nursing implications related to care of patients with servic dogs.

Background

The concept of using dogs to aid people with disabilities has been around for centuries. Examples of the use of dogs date as far back as the 9th century when dogs were provided to individuals with physical disabilities in a Belgian community (Shubert, 2012). In 1780, the use of a service dog for a blind man was first documented (Wenthold & Savage, 2007). Additionally, animals were used as a treatment for mental illness as early as the 18th century (Shubert, 2012). The first formal service dog school, The Seeing Eye, was opened in the United States in 1929 (Wenthold & Savage, 2007).

The use of service dogs has expanded significantly beyond the “seeing eye” dog. The use of service dogs has expanded significantly beyond the “seeing eye” dog. Dogs are used for a variety of services to aid their disabled handlers. Dogs assist their handlers with hearing, mobility, diabetes, seizures, allergies, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), among other conditions (Mills & Yeager, 2012; U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2016). Research findings support the effectiveness of dogs in sniffing out cancer cells for numerous cancers, including prostate (Cornu, Cancel-Tassin, Ondet, Girardet, & Cussenot, 2011), lung (Amundsen, Sundstrom, Buvik, Gederaas, & Haaverstad, 2014), ovarian (Horvath, Andersson, & Nemes, 2013), colon (de Boer et al., 2014), breast (Gordon et al., 2008), and melanoma (Cambell, Farmery, George, Farrant, 2013).

Lengthy waiting lists at training facilities further demonstrate the increasing demand for service dogs to assist people with disabilities (Winkle, Crowe, & Hendrix, 2012). Requests for information about service dogs to the National Service Dog Center rose from a few thousand requests in 1995 to well over 34,000 requests in 1999 (Duncan, 2000). As the use of service dogs increases, so will their presence in healthcare facilities.

Benefits to Patients

Patients benefit in many ways from service dogs. Healthy People 2020 seeks to improve health and “promote full community participation" for people with disabilities (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2014, para 1). Service dogs help people with disabilities better meet each of these goals. Not only do dogs assist handlers with their disabilities, but they can also provide emotional support (Hubert, Tousignant, Routhier, Corriveau, & Champagne, 2013; Fairman & Huebner, 2000). People with disabilities are more likely than their nondisabled counterparts to feel depressed or have low self-esteem (Collins et al., 2006).

The service dog often eliminates the social barriers that exist for those who have disabilities and this can make a significant difference to the lives of these patients. Members of the community smile more at people with service dogs than those who do not have a service dog (Eddy, Hart, & Boltz, 1998; Mader, Hart, & Bergin, 1989). The service dog often eliminates the social barriers that exist for those who have disabilities and this can make a significant difference to the lives of these patients (Mader, Hart, & Bergin, 1989). Studies have shown that people with physical disabilities report people talking to them when they were in public with their dog more often than when they were without their service animal (Lane, McNicholas, & Collis, 1998). These social interactions can facilitate a significant boost in self-esteem for those who have disabilities (Winkle, Crowe, & Hendrix, 2012).

Social interactions can have positive effects on abled-body children, promoting greater understanding and acceptance of their disabled peers (Mader, Hart, & Bergin, 1989). Multiple studies have shown that service dogs have not only a positive psychological but also a positive financial impact on children and adults with disabilities (Wenthold & Savage, 2007).

The economic impact of service dogs is manifested by increased independence. Hours of outside assistance needed are reduced for patients who have a service dog (Rintala, Maramoros & Seitz, 2008). Allen and Blascovich (1996) found that the use of a service dog decreased the need for paid assistance by 30 hours per week and greater independence was reported at home and in the community (Hubert et al., 2013). This increased independence can potentially lead to a decrease in hours lost in the workforce, possibly leading to a positive impact on the economy as a whole.

Access Challenges for Providers

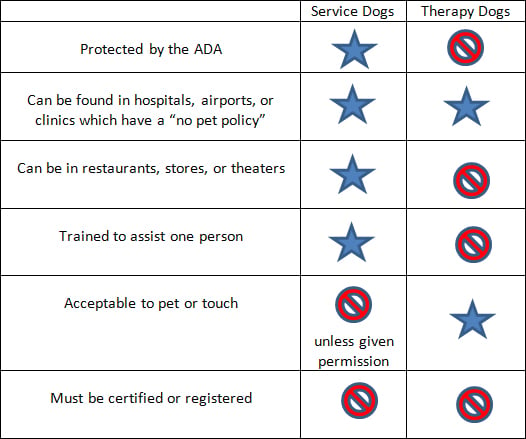

There is often confusion about differences between service dogs and therapy dogs. There is often confusion about differences between service dogs and therapy dogs. It is important to be able to distinguish between the two, as their roles are different and the laws surrounding them also vary. Service dogs are not pets: they are working animals (U.S. Department of Justice, 2010; US Department of Health & Human Services, 2016). These dogs are a tool for their handlers, the same as a wheelchair, glucometer, or a pair of glasses are for those who need them.

Service dogs work for one handler and they perform a trained task for that unique handler. Since they perform a trained task, they are protected under the Americans with Disabilities Act ([ADA], 2010; Nondiscrimination on the basis of disabilities in state and local government series, 2010). While the dog alone does not have public access rights, persons with a disability have public access rights that permit them to take their dogs with them into public places. These dogs are expected to work consistently and safely, often in public places that can be very distracting (Mills & Yeager, 2012).

While the ADA does not require certification for service dogs, Assistance Dogs International (ADI) has developed a set of standards that are recommended for service dogs. These standards include the ability of the service dog to perform at least three trained tasks that mitigate the patient’s disability, to remain close to the handler in public even if the leash is dropped, and to be unalarmed by loud noises or distractions (Parenti, Foreman, Meade, & Wirth, 2013). The dog is also expected to have behaviors and appearances that are appropriate in public (ADI, 2014).

Service dogs provide support for their owners, but they must also provide a trained task in order to qualify under the ADA. Emotional support dogs, whose functions are to provide comfort for their owners, are not covered under the ADA (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2016). Service dogs provide support for their owners, but they must also provide a trained task in order to qualify under the ADA. Psychiatric Service dogs are not emotional support dogs if they perform a trained task (Mills & Yeager, 2012). If the dog has a trained task, such as alerting someone to an oncoming panic attack or reminding a person to take their medication, this skilled task qualifies them as a service dog. This can be a subtle but important distinction.

Skills or training of a therapy dog are not specific to a person’s disability. Therapy dogs are not defined by federal law, but some states have made the distinction. These dogs have contact with people and provide service, but not just with people who have disabilities (Denholm, 2009; Delta Society, 2002). Skills or training of a therapy dog are not specific to a person’s disability. A therapy dog can very well be obediently trained, however, this is not a skilled task intended to assist a person with their disability (Parenti et al., 2013).

Therapy dogs are often seen in hospitals or healthcare facilities to diminish stress and act as distractions to patients. They can also be seen in elementary schools as reading dogs or in airports to reduce passenger anxiety. They can provide a great public service. Often, facilities acknowledge their benefits and will have policies in place that allow these dogs into areas that have “no pets allowed” policies. These dogs are meant to provide emotional support to more than one person. However, there is no federal protection that allows for public access for therapy dogs (Delta Society, 2002; Parenti et al., 2013).

Table 1: Differences between ADA Service Dogs and Therapy Dogs

ADA Laws and Service Dogs

Dogs in public places, including healthcare provider offices, may cause alarm for unknowing bystanders. There may be concern as to the legitimacy of the dog’s services and therefore its access to public places. According to the ADA (2010), only two questions about the dog are allowed: “Is that a service dog?” and “What task does the dog perform?” While these questions are vague, they are the only questions that are legally permitted. The patient may respond “yes, he is a service dog and he alerts to a medical condition.” The law prohibits asking for any further details or explanation.

The handler is not required to carry “proof” that the dog is a service dog. The handler is not required to carry “proof” that the dog is a service dog. No documents can be requested and a vest for the dog is not required. However, most service dogs will wear a vest and some handlers carry identification to help promote understanding of the service dog’s role. However, it should be noted that a vest and identification can easily be obtained without any proof that a dog is a service dog, making it harder to distinguish a real service dog from a fake.

While a well-trained service dog is unlikely to be disruptive, it can happen. The cost of professionally trained service dogs often leads to handlers self-training their dogs. There is a lack of nationally mandated standards or certifications. Therefore, it is possible to encounter a dog that is not adequately trained. If the service dog is a threat to the health and safety of others, handlers may be asked to remove the dog from the setting. Removal requests can also occur if the dog is being disruptive, is out of control of the handler, or is not properly house trained (Nondiscrimination on the basis of disabilities in state and local government series, 2010). However, assumptions about the dog’s behavior, fear, or mild allergies are not valid reasons to deny access to a service dog. (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2016).

Table 2: Service Dogs and the ADA Laws

|

Potential Challenges and Risks in Acute Care Settings

There are many challenges for patients and healthcare workers when using a service dog. Some of the challenges are legitimate hurdles that must be overcome, while others are only perceived risks. Many times, there are simple solutions for healthcare workers to minimize the challenges faced. The law states that service dogs cannot be denied access with their handlers in public areas that are non-sterile (Grace, 2013). This law applies to not only the patient but also visitors who use service dogs. The ADA (2010) states:

State and local governments, businesses, and nonprofit organizations that serve the public generally must allow service animals to accompany people with disabilities in all areas of the facility where the public is normally allowed to go (para. 6).

The nurse might be concerned about the wellbeing of other patients while a service dog is in the facility... fear of dogs and allergies are not valid reasons to request removal of a service dog. The nurse might be concerned about the wellbeing of other patients while a service dog is in the facility. What if another patient is allergic to dogs? What if the nurse is afraid of dogs? Is there an infectious disease risk? These are valid concerns and ones that are often encountered, however, fear of dogs and allergies are not valid reasons to request a service dog be removed (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2016).

Unlike a therapy dog, the service dog is only present in order to assist the handler. Therefore, interaction with other patients and staff should be minimal or absent. Reasonable accommodations can be made to ensure that the patient, service dog, and others are comfortable and safe. If a nurse is fearful or allergic, a simple solution is to change the staffing assignment. If a person has an allergy to dogs that is severe enough that it a limits “one or more major life activity” then the allergy is covered by the ADA. Both parties should receive reasonable accommodations (Denholm, 2009). It is imperative that the patient with a disability who uses a service dog is not isolated or treated differently than others who do not have a service dog (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2016).

It is important to clearly differentiate between actual risks and perceived risks. Infectious Disease. It is important to decrease risk of infection to patients regardless of whether the risk comes from staff, visitors, or a service animal. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends minimal contact with saliva, dander, or waste elimination from dogs, and that those who come into contact with the dogs should wash their hands with soap and water (Sehulster & Chinn, 2003). The risk for transmission of disease from canine to human is low and can be diminished with careful planning and basic hygiene (Denholm, 2009). The CDC recommends that service dogs be allowed in healthcare facilities under the ADA unless significant harm exists. It is the responsibility of healthcare facilities to make reasonable modifications in policies and procedures to reduce risks instead of simply denying access (Sehulster & Chinn, 2003). It is important to clearly differentiate between actual risks and perceived risks.

Many problems of having a service dog in healthcare facilities arise from lack of adequate policies... Acute Care Settings Policies and Guidelines. Many obstacles of having a service dog in healthcare facilities arise from lack of adequate policies; policies that contradict federal guidelines; and the healthcare team’s limited exposure to and understanding of service dogs. Healthcare facilities should have clear policies and procedures in place for staff to use as a guide. These policies should be in compliance with federal ADA laws. Policies should clearly define the difference between therapy dogs and service dogs, as procedures and access are different for the two types of dogs. Policies should address and/or include the following information:

- Definition of service dog.

- How service dogs differ from therapy dogs.

- Questions staff are permitted to ask: “Is that a service dog?” and “What skilled task does the service dog perform?”

- Access areas permitted/not permitted. Service dogs are allow to accompany handlers in all areas of a medical facility open to patients, visitors, and personnel as long as the dog’s presence does not pose a direct threat to others nor alter the facility’s proper functioning. A direct threat must be a significant risk to the safety or health of others, where reasonable accommodations cannot be made to mitigate this risk. Risks must be actual and not perceived risks. Exceptions are made for places in which special infection control measures are in place, such as a burn unit or operating room.

- Criteria for dog removal. A handler should not be asked to remove his or her service dog unless the dog is incontinent or displays threatening behavior beyond the handler’s control. It is important to realize that some behaviors might appear disruptive, such as barking, but may actually be a trained task, such as alerting to a change in patient condition. The handler must maintain control of the dog at all times, either through tethering, harness, leash, or voice command (ADA, 2010; CDC, 2003; Nondiscrimination on the basis of disabilities in state and local government series, 2010).

Clear policies and procedures are guidelines for staff to follow when they encounter a patient who has a service dog. Providing inservice education can familiarize staff with policies and laws, and their responsibilities as healthcare providers.

HIPAA. While the presence of a service dog might give information about a patient’s disability, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) laws must be followed at all times. If a dog is wearing a vest that says “Diabetic Alert Dog”, it can be assumed by other patients and staff that the handler has diabetes. The disability may not always be so obvious.

Merely discussing a patient with a service dog might be as much an identifier as the patient’s name. Some handlers are willing to share the skillset of their service dogs with medical staff, but others are not so inclined. It can be tempting to discuss the patient with the “cool dog” at the nurse’s station or in the elevator; however, it is important to remember that this patient deserves the same privacy as all patients. Merely discussing a patient with a service dog might be as much an identifier as the patient’s name.

The Role of the Healthcare Professional

Healthcare providers should not pet or talk to the dog unless granted permission by the handler. It may be tempting for the healthcare team to interact with a service dog, but the dog is working and should not be distracted (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2016). Healthcare providers should not pet or talk to the dog unless granted permission by the handler. Remember that the reason for the dog’s presence is to help the disabled partner. The dog should be out of the way so as not to interfere with care being provided. The healthcare team is not responsible for caring for the service dog. If the patient is too ill to care for the dog, it is the patient’s responsibility to arrange care for the animal.

It is the role of the healthcare team to incorporate the service dog into a holistic plan of care for the patient. It is the role of the healthcare team to incorporate the service dog into a holistic plan of care for the patient. Healthy People 2020’s disability and health objectives advise patients with a disability, “...must have opportunities to take part in meaningful daily activities that add to their growth, development, fulfillment, and community contribution” (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2014, para. 2). For many patients, their service dog is the link that allows them better access to care and the environment around them. The service dog is an essential lifeline, regardless of whether they are in a medical facility or functioning in daily life. Healthcare providers must acknowledge the benefits of a service animal in order to prevent unacceptable gaps in care.

While there are laws and policies regarding service dogs in healthcare facilities, providing patient-centered care requires the healthcare team to be innovative. It has been well documented that service dogs provide emotional support to their handler (Hubert et al, 2013; Collins et al., 2006). Their presence alone can alleviate stress or fear. There have been instances when the service dog has a skill that medical science cannot provide. At times, the dog can be a better intervention than those provided by medical equipment. The following exemplar demonstrates many of the ideas discussed in this article.

Exemplar

JJ’s presence was not intended as a comfort measure for KK, but as a tool to help her surgical team monitor for impending reactions. On December 18, 2013, a white, terrier mix, medical alert dog named JJ made international news when she accompanied her 7-year-old handler, KK, and trainer, into a procedure room. KK was having a procedure under anesthesia at Duke University Hospital in Durham, NC (Quinllin, 2013; Osunsami, 2014). JJ’s presence was not intended as a comfort measure for KK, but as a tool to help her surgical team monitor for impending reactions. KK has a rare condition called mastocytosis and anesthesia is a well-documented risk for patients with this condition (Carter, Uzzaman, Scott, Metcalfe, & Quezado, 2009). KK had had reactions to anesthesia in the past. JJ had demonstrated incredible skill at alerting when KK was in the early stages of a reaction. She would alert before any signs of the reaction were present on the medical equipment. She had alerted an impending reaction minutes before changes were observed on telemeter or pulse oximetry. In time-sensitive situations, identifying reactions early can allow patients like KK to be medicated quickly, preventing life-threatening anaphylaxis.

Photo included with permission.

During the procedure, JJ showed pre-alert behaviors when KK was coming out of anesthesia and adjustments were made by the team as a result. KK proceeded through the procedure without any major reactions or complications. JJ was handled by her trainer, who interpreted her behavior to KK’s surgical team and ensured that JJ’s presence did not interfere with sterile fields or the care provided by KK’s surgical team.

While JJ’s presence in a procedure room was not covered by the ADA, KK’s surgical team felt that the benefits far outweighed the risks. While JJ’s presence in a procedure room was not covered by the ADA, KK’s surgical team felt that the benefits far outweighed the risks. The surgical team requested special permission from administration to have JJ and her trainer in the room during the procedure. KK underwent a non-sterile procedure that required high-risk anesthesia as a result of her underlying condition of mastocytosis. The anesthesiologist remarked, “It sounds silly, in this age of technology, when we have millions of dollars’ worth of equipment beeping around me, that we had a little dog who was more sensitive than all the machines” (Quinllin, 2013).

Having service dogs in procedure rooms while patients are under anesthesia is unlikely to become common practice; however, it does offer a great example of patient-centered care. Ambardekar, Litman, and Schwartz (2013) described a situation where a service dog was permitted to accompany a patient and “helped” administer anesthesia by assisting the nurse in pushing the medication with his paw. The service dog’s presence prior to surgery was calming to the autistic patient. The skills that these dogs possess are often underestimated. Sometimes it might be in a patient’s best interest for the service dog to be at his or her side, even if it is not protected by the ADA.

Photo included with permission.

Future Recommendations and Nursing Implications

As the role of the service dog in plans of care continues to expand, so will the number of service dogs entering the healthcare arena. Research about their use and patient benefits should be further explored. There is little current, relevant research in this area and this lack of evidence leaves nurses uninformed about the use of service dogs and the role of nurses caring for patients who have them.

Table 3: Nursing Implications

|

Conclusion

Understanding the roles of service dogs can help patients who use these dogs, as well as those who might have conditions where a service dog could be beneficial. As the use of service dogs increases, the likelihood of encountering a patient with a service dog also rises. Whether in the primary or acute care settings, patients with disabilities who use a service dog will benefit from healthcare workers with greater awareness about laws and standards regarding the dog’s presence in healthcare facilities. Nurses should understand and consider the variety of ways in which service dogs might help other patients. Understanding the roles of service dogs can help patients who use these dogs, as well as those who might have conditions where a service dog could be beneficial.

Perhaps the most therapeutic intervention for the patient may be the potential benefit of a service dog, and not a new medication or medical device. Healthcare teams and facilities that are educated about relevant ADA laws and policies are in the best position to implement holistic plans of care for patients who rely on service dogs to diminish the effects of their disability.

Author

Michelle Krawczyk, DNP, ARNP-BC

Email: mkrawczyk@chamberlain.edu

Michelle Krawczyk is a nurse practitioner who is currently working in academia. She is the handler for her 10 year old daughter’s service dog, JJ. She helps to educate healthcare workers and the public about the role of service dogs as well as promotes the rights of disabled persons who use service dogs. She also is on the Board of Directors for Eyes Ears Nose and Paws, a nonprofit who trains service dogs for those with disabilities.

References

Allen, K. & Blascovich, J. (1996). The value of a service dog for people with severe ambulatory disabilities: A randomized controlled trial. JAMMA, 275 (13), 1001-1006.

Ambardekar, A. P., Litman, R. S., & Scwartz, A. J. (2013). “Stay, give me your paw.” The benefits of family centered care. Anesthesia-Analgesia, 116(6),1314-1316. doi:10.1213/ANE.0b013e31827ab89c

Amundsen, T., Sundstrom, S., Buvik, T., Gederaas, O. A., & Haaverstad, R. (2014). Can dogs smell lung cancer? First study using exhaled breath and urine screening in unselected patients with suspected lung cancer. Acta Oncologica, 53(3), 307-315. doi:10.3109/0284186X.2013.819996

Americans with Disabilities Act. (2010). Service dogs. Retrieved from http://www.ada.gov/service_animals_2010.htm

Assistance Dogs International. (2014). ADI minimum standards and ethics. Retrieved from http://www.assistancedogsinternational.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/ADI_MINIMUM_STANDARDSETHICS_08-2014.pdf

Cambell, L. F., Farmery, L., George, S. M., Farrant, P. B. (2013). Canine olfactory detection of malignant melanoma. BMJ Case Reports, doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-008566.

Carter, M. C., Uzzaman, A., Scott, L.M., Metcalfe, D. D., & Quezado, Z. (2009). Pediatric Mastocytosis: Routine anesthetic management for a complex disease. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 107 (2), 422-427.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2003). Guidelines for environmental infection control in health-care facilities. Atlanta, GA: Author. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hicpac/pdf/guidelines/eic_in_HCF_03.pdf

Collins, D. M., Fitzgerald, S. G., Sachs-Ericsson, N., Scherer, M., Cooper, R. A., & Boninger, M. L. (2006). Psychosocial well-being and community participation of service dog partners. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 1(1-2), 41-48.

Cornu, J. N., Cancel-Tassin, G., Ondet, V., Girardet, C., & Cussenot, O. (2011). Olfactory detection of prostate cancer by dog sniffing urine: A step forward in early diagnosis. European Urology, 59(2), 197-201.

de Boer, K. H., de Meij, T. G., Oort, F. A., Larbi, I. B., Mulder, C. K., van Bodegraven, A. A., & van der Schee, M. P. (2014). The scent of colorectal cancer: Detection by volatile organic compound analysis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hematology, 12(7), 1085-1089. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2014.05.005

Denholm, B. (2009). Service dogs in health care facilities. AORN, 89 (4), 757-760. doi:10.1016/j.aorn.2009.03.011

Delta Society. (2002, November). Minimum standards for service dogs. Retrieved from http://puppieswithapurpose.org/Resources/MInimum%20requirements%20for%20service%20animals.pdf

Duncan, S. L. (2000). APIC state of the art report: The implications of service animals in health care settings. American Journal of Infection Control, 28 (2), 170-180.

Eddy, J., Hart, L. A., & Boltz, R. P. (1988). The effects of service dogs on social acknowledgements of people in wheelchairs. Journal of Psychology, 12 (39).

Fairman, S. K. & Hubner, R. A. (2000). Service dogs: A compensatory resource to improve function. Occupation Therapy in Health Care, 13 (2), 41-52.

Gordon, R. T., Schatz, C. B., Myers, L. J., Kosty, M., Gonczy, C., Kroener, J…Zaayer, J. (2008). The use of canines in the detection of human cancers. Journal of alternative and complementary medicine, 14(1), 61-67. doi:10.1089/acm.2006.6408

Grace, K. (2013, October 2). Hospital access rights for service dog teams. Retrieved from http://anythingpawsable.com/hospital-access-rights-service-dogs/

Horvath, G., Andersson, & Nemes, S. (2013). Cancer odor in the blood of ovarian cancer patients: A retrospective study of detection by dogs during treatment, 3 and 6 months afterward. BMC Cancer, 13, 396. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-13-396.

Hubert, G., Tousignant, M., Routhier, F., Corriveau, H., & Champagne, N. (2013). Effect of service dogs on manual wheelchair users with spinal cord injury: A pilot study. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 50 (3), 341-350.

Lane, D. R., McNicholas, J., & Collis, G. M. (1998). Dogs for the disabled: Benefits to recipients and welfare of the dog. Applied Animal Behavior Science. 59. 49-60. doi:10.1016/S0168-1591(98)00120-8

Mader, B., Hart, L. A., & Bergin, B. (1989). Social acknowledgement for children with disabilities: Effect of service dogs. Child Development, 60, 1529-1534. DOI: 10.2307/1130941.

Mills, J. T. & Yeager, A. F. (2012, April-June). Definition of animals used in healthcare settings. The Army Medical Department Journal. 12-17.

Nondiscrimination on the basis of disabilities in state and local government series: Final rules. 28 CFR 35 (2010).

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2014). Healthy people 2020. Retrieved from https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/disability-and-health

Osunsami, S. (2014, January 7). Little girl’s best friend helps her stay safe even in surgery. [ABC World News Tonight with Diane Sawyer]. New York, NY: ABC News.

Parenti, L, Foreman, A., Meade, J., & Wirth, O. (2013). A revised taxonomy of assistance animals. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 50, (6), 745-756. doi:10.1682/JRRD.2012.11.0216

Quinllin, M. (2013, December 19) Little service dog has big job as Cary girl goes into surgery. The News and Observer.

Rintala, D. H. Matamoros, R., & Seitz, L. L. (2008). Effects of assistance dogs on persons with mobility or hearing impairments: A pilot study. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 45 (4), 489-503.

Sehulster, L. & Chinn, R. Y. (2003). CDC Guidelines for environmental infection control in health-care facilities, 52 (RR10). 1-42. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5210a1.htm

Shubert, J. (2012). Dogs and human health/mental health: From the pleasure of their company to the benefits of their assistance. The Army Medical Department Journal. April- June.

US Department of Health & Human Services. (2016). Understanding how to accommodate service animals in healthcare facilities Retrieved from http://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/planning/abc/Documents/service-animals.pdf

US Department of Justice. (2010). Service animals. Retrieved from https://www.ada.gov/service_animals_2010.htm

Wenthold, N. & Savage, T. A. (2007). Ethical issues with service animals. Topics in stroke rehabilitation, 14 (2), 68-74.

Winkle, M., Crowe, T. K., & Hendrix, I. (2012). Service dogs and people with physical disabilities partnerships: A systematic review. Occupational Therapy International, 19, 54-66. doi:10.1002/oti.323