The complexity of healthcare calls for interprofessional collaboration to improve and sustain the best outcomes for safe and high quality patient care. Historically, rehabilitation nursing has been an area that relies heavily on interprofessional relationships. Professionals from various disciplines often subscribe to different change management theories for continuous quality improvement. Through a case review, authors describe how a large, Midwestern, rehabilitation hospital used the crosswalk methodology to facilitate interprofessional collaboration and develop an intervention model for implementing and sustaining bedside shift reporting. The authors provide project background and offer a brief overview of the two common frameworks used in this project, Lewin’s Three-Step Model for Change and the Lean Systems Approach. The description of the bedside shift report project methods demonstrates that multiple disciplines are able to utilize a common framework for leading and sustaining change to support outcomes of high quality and safe care, and capitalize on the opportunities of multiple views and discipline-specific approaches. The conclusion discusses outcomes, future initiatives, and implications for nursing practice.

Key words: Outcomes, quality improvement, interprofessional collaboration, Lewin, Lean, crosswalk, case review, outcomes

Providing today’s healthcare requires professional collaboration among disciplines to address complex problems and implement new practices, processes, and workflows. Providing today’s healthcare requires professional collaboration among disciplines to address complex problems and implement new practices, processes, and workflows (AACN, 2011; Bridges, Davidson, Odegard, Maki, &Tomkowski, 2011; IOM, 2011). Often this collaboration magnifies competing or alternative discipline specific theories, language, and strategies to lead and sustain change management and to implement and support Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI) projects. Initially, professionals may perceive these differing views as mutually exclusive.

Lewin’s Three-Step Model Change Management is highlighted throughout the nursing literature as a framework to transform care at the bedside (Shirey, 2013). One criticism of Lewin’s theory is that it is not fluid and does not account for the dynamic healthcare environment in which nurses function today (Shirey, 2013). With the need to streamline resources and provide quality and safe healthcare, nurse leaders have focused on a rapid cycle approach to lead and sustain quality improvement changes at the bedside. One specific approach that is gaining rapid attention in healthcare is the “Lean System” for transformation. Experts assert that Lewin’s theory provides the fundamental principles for change, while the Lean system also provides the particular elements to develop and implement change, including accountability, communication, employee engagement, and transparency. The purpose of this case review is to describe how one large, Midwestern, rehabilitation facility used a crosswalk methodology to promote interprofessional collaboration and to design an intervention model comes to implement and sustain bedside shift reporting.

Project Background: Setting, Theoretical Bases, and Topic of Interest

Founded in the mid-1950s, this 182-bed, acute, inpatient rehabilitation facility (IRF) is located in a large Midwestern city and known for its commitment to promoting interprofessional and collaborative patient care. Rehabilitation is an interprofessional practice by nature that requires physiatrists, nurses, occupational therapists, speech therapists, physical therapists, and ancillary departments to collaborate to identify and achieve patient goals and outcomes. In early spring of 2017, the IRF will open a new research hospital to replace the current building. The new research hospital, a private, not-for-profit acute in-patient and outpatient rehabilitation facility, will expand patient care and combine research activities that translate directly to patient care in real time to improve patient outcomes.

This evolving research hospital environment requires that nurse executives demonstrate collaborative problem solving across the spectrum of care. Nurse leaders and executives’ formal training supports frequent use of Lewin’s Three-Step Model for Change Management. Meanwhile, healthcare institutions’ performance improvement departments often institute the Lean Systems Approach to quality improvement (Toussaint & Berry, 2013; Toussaint & Gerad, 2010).

Integrating language from the Lean model within the theoretical basis of change theories used by the IRF healthcare culture would likely be a key factor for success continuous quality improvement activities. The IRF executive leadership team identified that the organization was reliable in initiating improvements, but was challenged to sustain and spread improvements throughout the organization. The Lean model had been adapted as the improvement system for the IRF. Integrating language from the Lean model within the theoretical basis of change theories used by the IRF healthcare culture would likely be a key factor for success continuous quality improvement activities. The Director of Performance Improvement gained leadership team approval to lead an effort to connect the Lean System tools with concepts that were common to several change management theories or frameworks, such as Diffusion of Innovations Theory; Donabedian’s Structure, Process, and Outcomes Framework; and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) Rapid Cycle Improvement Model, including Lewin (Donabedian, 2003; IHI, 2001; Lewin, 1951; Rogers, 2003).

Concurrently, the manager of nursing outcomes met with her clinical nursing team to plan a pilot project for bedside shift reporting (BSR). Ultimately, this project serves to coalesce the aforementioned simultaneous events of the new research environment of the facility and the combination of change theory and Lean model concepts into a workable framework for interprofessional collaboration. While the BSR is not the focus of this case review, this project served as a catalyst for the interprofessional collaboration among executives; mid-level and staff nurses; performance improvement professionals; the patient-family education resource center; and director of ethics. The purpose of this article is to discuss an interprofessional collaboration that sought consensus among members of different disciplines who typically utilized different theoretical approaches to problem solving. We selected the crosswalk method to further collaboration and to create an intervention model for BSR. As BSR happened to be a substantive topic of interest to the organization, a natural opportunity emerged to display the utility of a crosswalk method as a tool to developing an intervention model.

Brief Overview: Lewin’s Model for Planned Change and the Lean Systems Approach

Inherent in interprofessional collaboration is a requisite that each discipline shares an understanding of the similarities and a common language of the change process... With the current emphasis on interprofessional problem-solving approaches for CQI in mind, collaboration becomes an essential part in delivering quality care and leading CQI projects (AACN, 2011; Bridges et al., 2011; IOM, 2011). Inherent in interprofessional collaboration is a requisite that each discipline shares an understanding of the similarities and a common language of the change process it proposes to use to develop an intervention model. Because the language and perspectives differ, professionals often struggle to find common ground for understanding so that each discipline maintains an influence. Historically, many nurses have subscribed to Lewin’s Three-Step Model for Change (Shirley 2013). For the past 10 years, the Lean System Approach has been at the forefront of efforts to implement and sustain change in healthcare delivery organizations (D'Andreamatteo, Lappi, Lega, & Sargiacomo, 2015). This section provides a brief overview of Lewin’s Three-Step Model for Change and the Lean System Approach to change.

Lewin’s Three-Step Model for Change

Healthcare organizations are complex adaptive systems where change is a complex process with varying degrees of complexity and agreement among disciplines. The Change Model. Complex adaptive systems require that, in order for organizations to maintain equilibrium and survive, the organizations must respond to an ever-changing environment. Healthcare organizations are complex adaptive systems where change is a complex process with varying degrees of complexity and agreement among disciplines (Plsek & Greenhalgh, 2001; Porter-O’Grady & Malloch, 2011). Lewin’s Change Management Theory (Lewin, 1951) is a common change theory used by nurses across specialty areas for various quality improvement projects to transform care at the bedside (Chaboyer, McMurray, & Wallis, 2010; McGarry, Cashin & Fowler, 2012; Shirey, 2013; Suc, Prokosch & Ganslandt, 2009; Vines, Dupler, Van Son, & Guido, 2014).

Lewin’s theory proposes that individuals and groups of individuals are influenced by restraining forces, or obstacles that counter driving forces aimed at keeping the status quo, and driving forces, or positive forces for change that push in the direction that causes change to happen. The tension between the driving and restraining maintains equilibrium. Changing the status quo requires organizations to execute planned change activities using his three-step model. This model consists of the following steps (Lewin 1951; Manchester, et al., 2014; Vines, et al., 2104).

- Unfreezing, or creating problem awareness, making it possible for people to let go of old ways/patterns and undoing the current equilibrium (e.g., educating, challenging status quo, demonstrating issues or problems)

- Changing/moving, which is seeking alternatives, demonstrating benefits of change, and decreasing forces that affect change negatively (e.g., brainstorming, role modeling new ways, coaching, training)

- Refreezing, which is integrating and stabilizing a new equilibrium into the system so it becomes habit and resists further change (e.g., celebrating success, re-training, and monitoring Key Performance Indicators [KPIs])

Other Considerations. Criticisms of Lewin’s change theory are lack of accountability for the interaction of the individual, groups, organization, and society; and failure to address the complex and iterative process of change (Burnes, 2004). Figure 1 depicts this change model as a linear process.

Figure 1. Lewin’s Three-Step Model for Planned Change

However, in addition to change theory, healthcare has also shifted to a robust system for change called the Lean Systems Approach.

Lean Systems Approach

The Lean Model. The Lean Systems Approach (Lean) is a people-based system, focusing on improving the process and supporting the people through standardized work to create process predictability, improved process flow, and ways to make defects and inefficiencies visible to empower staff to take action at all levels (Liker, 2004; Toussaint & Gerard, 2010). To that end, Lean creates value for internal and external customers through eliminating waste (e.g., time, defects, motion, inventory, overproduction, transportation, processing). To create value and meet customer needs, Lean resources are provided in a robust toolkit. Value stream mapping is a tool to identify process relating to material and information and people flow. It is useful to identify value added and non-value added actions. Value stream mapping is then used to create a plan to eliminate waste, create transparency (visual management), implement standard work, improve flow, and sustain change.

...Lean is a way of thinking about improvement as a never-ending journey. Overall, Lean is a way of thinking about improvement as a never-ending journey. Lean starts as a top-down, bottom-up approach, requiring leadership support. Over time, the goal is for all staff to contribute to problem solving and designing improvements to add value as defined by the customer. Value is defined as the services that the customer is willing to purchase (Toussaint &Gerard, 2010).

In healthcare, adding value or meeting the customer or patient needs often occurs at the bedside, and nurses who provide care are closest to the bedside. Lean offers a common system, philosophy, language, and tool kit for improvement. Many quality improvement approaches have parallels and one well known is Deming’s Improvement Model of Plan, Do, Check, Act (Deming Institute, 2015). Deming’s model is also utilized in the Lean approach as a structure to make and sustain improvements. The IHI refers to this as Plan, Do, Study, Act-Rapid Cycle Improvement Model (Scoville & Little, 2014). Both models, like Lean, strive for structure, methods, and improvement that never ends – continuous improvement, or Kaizen, in Lean terms. For an organization to reap the full benefit of the Lean approach, it is necessary to integrate a system-wide approach (D’Andreamatteo et al., 2015; Liker, 2004; Toussaint, 2015). Lean tools are designed to work together to maximize improvements within an organization and create a culture that embraces the journey of continuous quality improvement.

...the Lean System exemplifies a culture where each staff member is empowered to make change. To this end, the Lean System exemplifies a culture where each staff member is empowered to make change. This culture focuses on creating value, supporting staff, and improving process flow to increase quality, reduce costs, and increase efficiency. Interprofessional collaboration is a necessary component to make improvements that involve going to the gemba (i.e., where the work is done or patient floor), to observe with our own eyes, ask questions, and learn. Other aspects of Lean are the importance of utilizing data and identifying root cause (5 Why’s, or asking why five times). Becoming a learning organization by creating a safe environment to make mistakes (taking into account patient safety) is key in Lean; it is better to try, fail, learn, adjust, than to not try at all (Simon & Canacari, 2012). The Lean tools provide a medium for staff to break down problems, eliminate non-value added activities, and not only implement a new standard process, but sustain it as well (Kimsey, 2010; Liker, 2004; Mann, 2010).

Kaizen, or continuous improvement, means adjusting how healthcare organizations operate to create value. Other Considerations. Incorporating Lean into the healthcare industry has been met with barriers. A common reaction to Lean within healthcare is that it only applies to manufacturing cars (e.g., the Toyota Production System) (Liker, 2004; Toussaint & Gerad, 2010; Toussaint & Berry, 2013). This reaction, in itself, becomes a barrier to apply and incorporate Lean into the healthcare industry. The interpretation of standard work being inflexible is also a barrier within healthcare. Standard work can be made flexible to adjust to unique patient scenarios and change according to changes in the healthcare environment, technology, and patient needs. Kaizen, or continuous improvement, means adjusting how healthcare organizations operate to create value. Many hospitals have been applying Lean, such as Virginia Mason Medical Center, ThedaCare, Mayo Clinic, and Seattle Children’s Hospital (Toussaint & Berry, 2013). Furthermore, regulatory changes, such as those from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), and pressure on healthcare organizations to deliver high quality, safe and cost-effective care (Toussaint & Berry, 2013).

[A no-blame culture] creates an environment whereby any member(s) of the organization can take action to improve performance and outcomes. Healthcare can often be a shame and blame culture, which is very different than Lean (Simon & Canacari, 2012; Toussaint & Gerad, 2010). A fundamental principle of Lean is that it attacks the process rather than the person or people to create a no-blame culture. The Lean Systems Approach is designed to build trust, engage staff to trystorm (try ideas rapidly to see if they work), measure improvement, and implement and sustain. The Lean System is designed for problems to rise to the surface and become transparent so that they can be addressed. This transparency (visual management), along with clear measures and coaching, keeps important concerns in view of staff. This creates an environment whereby any member(s) of the organization can take action to improve performance and outcomes (Mann, 2010).

Considering concepts from both Lewin’s Three-Step Model for change and the Lean Systems Approach opens the possibility of using the best of each of these models to facilitate interprofessional collaboration and a problem-solving approach. Through interprofessional collaboration, nursing and other disciplines can continue to improve processes and outcomes for the greater good of patient outcomes and the healthcare industry (Brooks, Rhodes & Tefft, 2014). The next section offers a short explanation of the concept of interprofessional collaboration, which served as the problem-solving basis of our project to develop an intervention model for bedside shift reporting.

Interprofessional Collaboration: A Problem Solving Approach

...collaboration can enhance collegial relationships and collapse professional silos, as well as improve patient outcomes. In one of the more widely-cited definitions of collaboration, Gray (1989) describes "a process through which parties who see different aspects of a problem can constructively explore their differences and search for solutions that go beyond their own limited vision of what is possible” (p. 5). Collaboration involves multiple disciplines that span across individual professional silos, hence the term interprofessional is used for this case review. Collaboration is based on a naturalistic inquiry process, whereby each party takes on the teacher role, educating others, and the learner role, an openness and willingness to receive information from others, relinquishing power and control to move beyond their own perspectives for benefit of change (Denzin & Lincoln, 2011; Gray, 1989).

Communication serves as a mechanism for sharing knowledge and is the hallmark for improving working relationships (Gray, 1989). Collaborative efforts create spaces where connections are made, ideas are shared, opportunities for innovation flourish, and strategies for change to transpire (London, 2012). Today, healthcare associations and committees work diligently to ensure that interprofessional collaboration is part of their educational curriculum and practice standards.

The American Nurses Association (ANA, 2009) lists “collaboration” as a standard of practice for nursing administration. Similarly, the Institute of Medicine (IOM, 2011) recommends that “nurses should be full partners, with physicians and other health professionals, in redesigning healthcare in the United States” (p. 32).

Nursing driven improvement projects and change initiatives that require interprofessional collaboration are common in redesigning healthcare delivery. However, simply grouping healthcare professionals from differing disciplines together to work on a project does not always cultivate collaboration (Kotecha et al., 2015). Effective interprofessional collaboration is a blending of professional cultures that arises from sharing knowledge and skills to improve patient care, and exhibits accountability, coordination, communication, cooperation, and mutual respect among its members (Bridges et al., 2011; Reber, et al., 2011). Such collaboration can enhance collegial relationships and collapse professional silos, as well as improve patient outcomes (Kotecha et al., 2015.).

There are facilitating and hindering factors for interprofessional collaboration associated with nursing driven projects (Tviet, Belew, & Noble, 2015). Facilitating factors cited include: identifying key roles and individuals; soliciting early involvement and commitment from individuals and the group; and continuing to monitor progress and compliance well after implementation, including follow up with staff whose compliance is low. Hindering factors cited include: difficulty coordinating meeting times among multiple professions; bias of each profession as to what would work for them; discipline specific professional jargon; and the ability of one person or group to resist change and stop the project from moving forward (Ellison, 2014).

Interprofessional collaboration lessens discipline-specific perspectives, thus improving quality of care and patient outcomes, and increasing efficiency and reducing healthcare resources. Interprofessional collaboration lessens discipline-specific perspectives, thus improving quality of care and patient outcomes, and increasing efficiency and reducing healthcare resources (Patton, Lim, Ramlow, & White, 2015). An initial effort by all parties to visually display alignments and confront differences may minimize frustration and miscommunication among professionals. As we considered the synergy of concepts from both the Lewin Three-Step Model for Change and Lean Systems Approach, our idea was to use crosswalk methodology to begin collaboration with an interprofessional perspective.

Crosswalk Methodology

The crosswalk is a robust qualitative method, often associated with theory building and inductive reasoning, which provides a compressed display or visual of meaningful information (Miles & Huberman, 1994). Table 1 demonstrates the utility of the crosswalk method across domains, with examples from various domains to make comparative evaluations among programs, assessment tools, and theories to determine alignments and misalignments. Advantages of conducting a crosswalk are that it elucidates key connections and critical opportunities for growth and knowledge expansion, equitable resource allocation, and inquiry; and it depicts a large amount of information in a clear and concise manner. Disadvantages of the crosswalk method are that it often lacks the rigor and depth necessary to make causal links or provide generalizable information (Miles & Huberman, 1994). However, since the goals of qualitative methods are not causal links or generalizability, crosswalks can offer an intentional, systematic method to consider complex information in a meaningful way.

Table 1. Examples: Utility of Crosswalk Across Domains

| Domain | Reference | Purpose |

| Academia | American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 2011 | To show interface between the nine master’s essentials against themes in the IOM’s report (2011). |

| Administration- | Rudisill & Thompson, 2012 | To conduct a gap analysis between required skills for nurse executives and competency assessment. |

| Clinical | Brandenburg, Worrall, Rodgriguez, & Bagraith, 2015 | To delineate self-report measures using two aphasia tools. |

| Clinical | Sink, et al., 2015 | To compare the findings of two mental state exams in the African Americans for accurate interpretation. |

| Public Policy, & Accreditation | Kamoie & Borzi, 2001 | To confirm congruency between the final HIPAA privacy rule and federal substance abuse policy. |

| Public Health Surveillance | Parsons, Enewold, Banks, Barrett & Warren, 2015 | To link unique physician identifiers from two national directories so that Medicare data can be used for research. |

| Public Health & Performance Management | Gorenflo, Klater, Mason, Russo, & Rivera, 2014; Kamoie & Borzi, 2001 | To demonstrate the robust congruencies between two performance management programs. |

| Research | Lai, Cella, Yanez, & Stone, 2014 | To further refine the psychometric properties of two fatigue scales. |

Bedside Shift Report Project Methods

Through a case review, we will describe how this IRF implemented a CQI process that integrated theory into practice via both Lewin’s theory and a Lean Systems Approach. We used crosswalk methodology to compare Lewin’s Theory and Lean, a process that ultimately led to collaboration and the creation of an intervention model for BSR. For this case, the crosswalk was used to visually examine the relationships, concepts, and language used within two approaches to change and quality improvement. Team members visualized the similarities and dissimilarities and adopted the teacher and learner role necessary to move the BSR project forward.

Our Team

Initially, an interprofessional team of six consisting of executives; mid-level and staff nurses; performance improvement professionals; the patient-family education and resource center; and director of ethics convened through semi-monthly work sessions from early spring 2015 to early fall 2015 for the purpose of BSR. During interprofessional work sessions, the language used among team members when discussing the improvement process differed, which resulted in confusion among members and became a barrier to collaboration.

What the team experienced was similar to what Andersen and Rovik (2015) described as the many interpretations of lean thinking. Different definitions or interpretations of concepts were being made, prolonging the improvement and sustaining process. D'Andreamatteo et al. (2015) suggested that “...a common definition should be established to distinguish what is Lean and what is not…” (p. 10). The team wanted all participants of the various disciplines to see the commonalities of approach, to create a better known definition of each concept, and to continue to build collaboration and understanding for better outcomes.

Visually showing theoretical connections helped improve the understanding of all team members and thus our process became more adoptable to the group. Team members identified the translation barrier very early when they conducted a crosswalk of concepts and language from Lewin’s Change Theory to the language of Lean tools and principles. Lean, being both a system and a way of thinking, and not just a quick process to make point improvements, was linked with Lewin’s, three-step model of planned change. This crosswalk, demonstrated in Table 2, launched the connection to understand improvement theory and techniques. Visually showing theoretical connections helped improve the understanding of all team members and thus our process became more adoptable to the group.

Our Process and Crosswalk

Once we determined a topic of interest (bedside reporting) our interprofessional team used the following process to problem solve:

- Convened an interprofessional working group consisting of executive, mid-level and staff nursing, performance improvement, the patient-family education resource center, and director of ethics;

- Reviewed literature on BSR to familiarize team with evidence-based practice for BSR;

- Reviewed Lewin Three-Step Model for Planned Change;

- Reviewed Lean System Approach for CQI;

- Created a crosswalk;

- Refined crosswalk based on team feedback;

- Finalized crosswalk (See Table 2);

- Presented to nursing staff-at-large to spread understanding.

The final crosswalk led to two outcomes, described below.

Table 2. Crosswalk: Lewin Change Theory and Lean Concepts

| Lewin (Stages) Examples of Concepts & Processes | Lean System (Not all inclusive) |

| Unfreezing

| Plan (Ask why is this a focus; collect data & information to tell story; define baseline)

|

| Moving

| Do

|

| Lewin (Stages) Examples of Concepts & Processes | Lean System (Not all inclusive) |

| Re-freezing-sustaining

| Check/Act (Sustain, stabilize, show improvement)

|

Our Outcomes

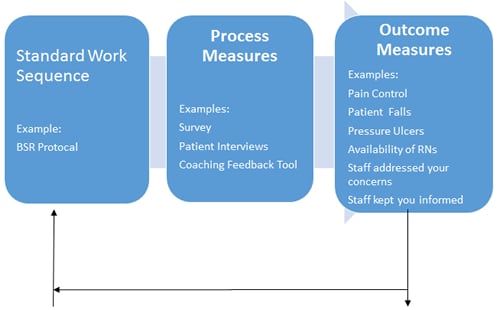

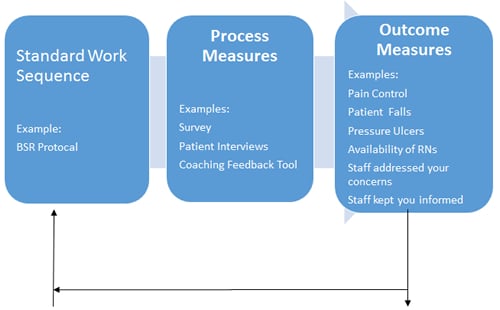

This case review illustrates two outcomes. The first outcome of our project was enriched interprofessional collaboration and the second outcome was an intervention model BSR (see Figure 2). These are briefly described below.

The rich interprofessional collaboration that resulted in our final crosswalk illustrated the compatibility between Lewin’s Theory and Lean, operationalized the stages of change, and provided tangible strategies and tools to implement and sustain a BSR project. This project will be implemented in 2016.

During a debriefing, the primary author (E.W) asked team members to comment about their experience with this CQI project. Anecdotal information illustrates furthered collaboration within this IRF. Team members verified the accuracy of the anecdotal information by reviewing its written form and gave permission for publication in this article.

The following remarks display three themes related to collaboration:

…the teacher-learner process where members move between educating others, and gaining knowledge by being open and willing to understand others; I came to the team with one idea about how to change systems for the benefit of patient care. …Initially, I felt the team was polarized due to their differing ways of thinking or points of view about change. Once we conducted the crosswalk between Lean and Lewin, I could visualize how we were saying similar things, but in a different way. I learned from my team members and I believe they learned from me. ... I listened and I also felt heard. [I] loved this experience and would use the crosswalk early in any interprofesssional project.

…the opportunity for innovative problem solving that transpired above your own world view for the common good; Nurses first came to the team with the feeling that Lean was just a passing fancy that would attempt to improve sustaining change and would fail and soon be forgotten. [However], they came away with useful tools to support their on-going challenges to continually improve patient care and nursing outcomes.

…the promotion for enhanced partnerships among professionals. Finding commonality in the Lewin and Lean languages and approach provided a way for our broader group to connect and discuss improvements in a proactive way. Recognizing we were not against one another but working towards the same goal for quality of care. Since this took crosswalk took place, our partnerships are tighter due to a better understanding of each other’s disciplines and perspective. We have a point of reference to go back to for discussion. Mutual respect was enhanced allowing us to have different conversations now with better focus on solutions.

As noted previously, the manager of nursing quality and her clinical staff had done preliminary work on BSR. The second outcome of our subsequent team work, the intervention model in Figure 2, assimilated and utilized Lean and Lewin tools and principles that comprise the Standard Work Sequence (i.e,, the BSR protocol). Examples of this protocol included:

- The design and target population of intervention

- Process measures, such as measures of the intended delivery of the intervention (e.g., survey assessing on thoroughness, accuracy and efficiency of the BSR, patient interviews, and staff coaching and feedback tool)

- Outcome measures, which included measures for the intended response or results of the intervention (e.g., pain control, patient falls, pressure ulcers, availability of RNs, staff addressing [patients’] concerns, and staff keeping patient informed)

Figure 2. Intervention Model for Beside Shift Reporting

This article describes the two outcomes resulting from our interprofessional collaborative team effort to address the topic of interest using an intentional theoretical approach. As the intervention model is implemented, baseline and follow-up data will be obtained on the process and outcomes measures listed above.

Conclusion

Developing and utilizing our crosswalk to educate nurses on the Lean philosophy and tools adopted by this organization for CQI also familiarized non-nursing members of the interprofessional team with Lewin’s work and the common nursing culture and language for change. It was the “aha” moment for all team members. This breakthrough led to further collaboration and demonstrated the commonalities between Lewin’s Three-Step Model for Change and the Lean Systems Approach philosophy for CQI. Collaboration enhanced nursing buy-in to this process and a better understanding of the application of Lean principles.

Critical to collaboration is that parties realize that talking about and planning collaboration does not mean that it will happen quickly and easily. Barriers to communicating and understanding the process were greatly reduced. At the conclusion, nurses could quickly and easily see the benefits of using this adaptive model to implement and sustain change. Critical to collaboration is that parties realize that talking about and planning collaboration does not mean that it will happen quickly and easily. Ultimately, the crosswalk offered two positive outcomes. The first was that it furthered interprofessional collaboration by engaging team members to clarify language and mental models of management approaches. The second outcome was the development of the intervention model for BSR project, taking preliminary work on a project by the Manager of Nursing Outcomes and her team to the next level, with an end product that is being implemented in 2016.

Future directions for our team are to determine the usefulness of the crosswalk for multi-discipline initiatives, such as the “patient up and ready” program, a joint initiative between nursing and allied health to ensure that patients are available and ready for each scheduled therapy session. In sum, the initial outcomes of this case review demonstrate willingness among providers in multiple disciplines to seek consensus in understanding and utilize a shared framework to lead and sustain change for high quality and safe patient care. Doing so capitalizes on the expanded knowledge and expertise of multiple views and discipline-specific approaches to change management.

Authors

Elizabeth Wojciechowski, PhD, PMHCNS-BC

Email: ewojciecho@ric.org

Elizabeth Wojciechowski is a doctorally prepared APN in mental health nursing with 25 years of experience in clinical management, strategic planning, graduate-level education, and qualitative and quantitative research. Her most recent professional experience as Education Program Manager and Project Consultant includes collaborating with professionals on hospital-wide change management projects; developing a website and hospital-wide patient and family education system; project lead for strategic planning for a new cancer rehabilitation center; and leading the inception of the nursing research committee. Former experience as an associate professor of nursing and a nurse manager includes serving on a university IRB board; teaching epidemiology, research, leadership and management at the graduate school level; developing and administering an outpatient dual-diagnosis program servicing children and families; and securing outside funding to pursue clinical research projects that resulted in publications in peer-reviewed journals and awards.

Tabitha Pearsall, AAB, Lean Certification

Email: tpearsall@ric.org

Tabitha Pearsall received a business degree in Seattle, WA and has 25 years operations experience, 11 years of experience utilizing Lean or Six Sigma improvement methodologies, with the last eight years focused in healthcare. She is Lean Certified through John Black & Associates, whose method is modeled after the Toyota Production System. She has implemented improvement programs in three organizations, two of which are in healthcare focused on Lean. Currently, Director of Performance Improvement at a large acute rehabilitation hospital, creating structure and implementing plan for integrating Lean methods and facilitating improvements hospital wide.

Patricia Murphy, MSN, RN, NEA-BC

Email: pmurphy@ric.org

Patricia J. Murphy has over 30 years of experience in nursing leadership and education. She currently is the Associate Chief Nurse at a large acute inpatient rehabilitation institute where she is responsible for the operations of seven inpatient-nursing units, the nursing supervisors, radiology, respiratory therapy, laboratory services, dialysis, and chaplaincy. In this leadership role, she identifies, facilitates, implements, supports, and monitors evidence based nursing practices, projects and nursing development initiatives in order to improve nurse sensitive patient outcomes and add to the body of knowledge of rehabilitation nursing practice. Former experience includes Director of Oncology Services and Hospice; strategic planning of a new cancer center; leading quality projects in oncology and within the stem cell transplant unit; designing and implementing an oncology support program; and developing and implementing a complementary therapy program to support inpatients, outpatients, and the community.

Eileen French, MSN, RN, CRRN

Email: efrench@ric.org

Eileen French received a BSN from Northern Illinois University and an MSN from Loyola University. She is certified in rehabilitation nursing and has worked for over 30 years at a large acute inpatient rehabilitation institute, as a direct care nurse, clinical educator, clinical nurse consultant, and nurse manager. She is currently Manager of Nursing Outcomes, and has led a group of nurses responsible for planning and initiating bedside shift report in this rehabilitation setting.

Brooks, V., Rhodes, B., & Tefft, N. (2014). When opposites don't attract: One rehabilitation hospital's journey to improve communication and collaboration between

nurses and therapists. Creative Nursing, 20(2), 90-94.

Burnes, B. (2004). Kurt Lewin and complexity theories: back to the future?

Journal of Change Mnagement, 4(4), 309-325. doi: 10.1080/1469701042000303811

Ellison, D. (2014). Communication Skills. Nursing Clinics of North America, 50(1),

45-57. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2014.10.004

References

American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2011). Crosswalk of the AACN master’s essentials and the IOM’s Future of Nursing: Leading change, advancing health recommendations. Retrieved from http://www.aacn.nche.edu/faculty/faculty-tool-kits/masters-essentials/Crosswalk.pdf

American Nurses Association. (2009). Nursing administration: Scope and standards of practice. (3rd ed.) Silver Springs, MD: American Nurses Association.

Andersen, H., & Rovik, K. A. (2015). Lost in translation: A case-study of the travel of lean thinking in a hospital. BMC Health Services Research, 15, 401. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-1081-z

Brandenburg, C., Worrall, L., Rodriguez, A., & Bagraith, K. (2015). Crosswalk of participation self-report measures for aphasia to the ICF: What content is being measured? Disability and Rehabilitation, 37(13), 1113-1124. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2014.955132

Bridges, D., Davidson, R., Odegard, P., Maki, I., & Tomkowski, J. (2011). Interprofessional collaboration: Three best practice models of interprofessionaleducation. Medical Education Online. doi: 10.3402/meo.v161i0.6035

Brooks, V., Rhodes, B., & Tefft, N. (2014). When opposites don't attract: One rehabilitation hospital's journey to improve communication and collaboration between

nurses and therapists. Creative Nursing, 20(2), 90-94.

Burnes, B. (2004). Kurt Lewin and complexity theories: back to the future?

Journal of Change Mnagement, 4(4), 309-325. doi: 10.1080/1469701042000303811

Chaboyer, W., McMurray, A., & Wallis, M. (2010). Bedside nursing handover: a case study. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 16(1), 27-34. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2009.01809.x

D'Andreamatteo, A., Ianni, L., Lega, F., & Sargiacomo, M. (2015). Lean in healthcare: A comprehensive review. Health Policy, 119(9), 1197-1209. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.02.002

The W. Edwards Deming Institute. (2015). The Plan, do study, act cycle (PDSA). Retrieved from https://www.deming.org/theman/theories/pdsacycle

Denzin, N. & Lincoln, Y. (2011). The Sage handbook of qualitative research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Donabedian, A. (2003). An introduction to quality assurance in health care. (1st ed., Vol. 1). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Ellison, D. (2014). Communication Skills. Nursing Clinics of North America, 50(1),

45-57. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2014.10.004

Gorenflo, G. G., Klater, D. M., Mason, M., Russo, P., & Rivera, L. (2014). Performance management models for public health: Public Health Accreditation Board/Baldrige connections, alignment, and distinctions. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 20(1), 128-134. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182aa184e

Gray, B. (1989).Collaborating: Finding common ground for multiparty problems. San Francisco, CA: Josey-Bass.

Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. (2011). Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: Report of an expert panel. Washington, DC: Interprofessional Education Collaborative. Retrieved from http://www.aacn.nche.edu/education-resources/IPECReport.pdf

Institute of Medicine. (2011). The Future of nursing: Leading change, advancing health. Retrieved from http://iom.nationalacademies.org/Reports/2010/The-Future-of-Nursing-Leading-Change-Advancing-Health.aspx

Kamoie, B., & Borzi, P. (2001). A crosswalk between the final HIPAA privacy rule and existing federal substance abuse confidentiality requirements. Issue Brief (George Washington University: Center for Health Service Research and Policy ), (18-19), 1-52.

Kimsey, D. (2010). Lean methodology in health care. AORN Journal, 92(1), 53-60. doi:10.1016/j.aorn.2010.01.015

Kotecha, J., Brown, J. B., Han, H., Harris, S. B., Green, M., Russell, G., . . . Birtwhistle, R. (2015). Influence of a quality improvement learning collaborative program on team functioning in primary healthcare. Families, System, & Health, 33(3), 222-230. doi: 10.1037/fsh0000107

Lai, J. S., Cella, D., Yanez, B., & Stone, A. (2014). Linking fatigue measures on a common reporting metric. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 48(4), 639-648. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.12.23

Lewin, K. C. (1951). Field theory in social science. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Liker, J. K. (2004). The Toyota Way: 14 Management Principles from the world’s greatest manufacturer. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

London, S. (2012). Building collaborative communities. In M. Bak-Mortensen & J. Nesbitt. (Eds.), On Collaboration (n.pag.). London: Tate. Retrieved from http://www.scottlondon.com/articles/oncollaboration.html

Manchester, J., Gray-Miceli, D. L., Metcalf, J. A., Paolini, C. A., Napier, A. H., Coogle, C. L., & Owens, M. G. (2014). Facilitating Lewin's change model with collaborative evaluation in promoting evidence based practices of health professionals. Evaluation and Program Planning, 47, 82-90. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2014.08.007

Mann, D. (2010). Creating a lean culture: Tools to sustain lean conversions (2nd ed.). New York: Productivity Press.

McGarry, D., Cashin, A., & Fowler, C. (2012). Child and adolescent psychiatric nursing and the 'plastic man': Reflections on the implementation of change drawing insights from Lewin's theory of planned change. Contemporary Nurse, 41(2), 263-270. doi: 10.5172/conu.2012.41.2.263

Miles, M. B. & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Parsons, H. M., Enewold, L. R., Banks, R., Barrett, M. J., & Warren, J. L. (2015). Creating a National Provider Identifier (NPI) to Unique Physician Identification Number (UPIN) crosswalk for Medicare data. Medical Care. doi: 10.1097/mlr.0000000000000462

Patton, C. M., Lim, K. G., Ramlow, L. W., & White, K. M. (2015). Increasing efficiency in evaluation of chronic cough: A multidisciplinary, collaborative approach. Quality Management in Health Care, 24(4), 177-182. doi: 10.1097/qmh.0000000000000072

Plsek, P. E., & Greenhalgh, T. (2001). Complexity science: The challenge of complexity in health care. BMJ, 323(7313), 625-628.

Porter-O’Grady, T. & Malloch, K. (2011). Quantum leadership: Advancing innovation, transforming healthcare (3rd ed.). Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Reber, P. A., DiPietro, E. A., Paraway, Y., Obst, B. P., Smith, R. A., & Koller, C. L. (2011). Communication: The key to effective interdisciplinary collaboration in the care of a child with complex rehabilitation needs. Rehabilitation Nursing, 36(5), 181-185, 213.

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of Innovations (5th ed.). New York, NY: Free Press.

Rudisill, P. T., & Thompson, P. A. (2012). The American Organization of Nurse Executives system CNE task force: A work in progress. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 36(4), 289-298. doi: 10.1097/NAQ.0b013e3182669453

Scoville R. & Little K. (2014). Comparing lean and quality improvement. IHI White Paper. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Retrieved from http://www.ihi.org/resources/pages/ihiwhitepapers/comparingleanandqualityimprovement.aspx

Shirey, M. R. (2013). Lewin’s theory of planned change as a strategic resource. Journal of Nursing Administration, 43(2), 69-72. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e31827f20a9

Simon, R. W. & Canacari, E. G. (2012). A Practical guide to applying lean tools and management principles to health care improvement projects. AORN, 95(1), 85-100; quiz 100-103. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2011.05.021

Sink, K. M., Craft, S., Smith, S. C., Maldjian, J. A., Bowden, D. W., Xu, J., . . . Divers, J. (2015). Montreal cognitive assessment and modified mini mental state examination in African Americans. Journal of Aging Research, 2015, 872018. doi: 10.1155/2015/872018

Suc, J., Prokosch, H. & Ganslandt, T. (2009). Applicability of Lewin s change management model in a hospital setting. Methods of Information in Medicine, 48(5), 419-28. doi: 10.3414/ME9235

Tviet, C., Belew, J., & Noble, C. (2015). Prewarming in a pediatric hospital: Process improvement through interprofessional collaboration. Journal of PeriAnesthesia Nursing, 30(1), 33-38. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2014.01.008

Toussaint, J.S. (2015). A Rapidly adaptable management system. Journal of Healthcare Management, 60(5), 312-315.

Toussaint, J. S. & Berry, L. L. (2013). The promise of lean in health care. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 88(1), 74-82. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.07.025

Toussaint, J. S., & Gerard, R. A. (2010). On the mend: Revolutionizing healthcare to save lives and transform the industry. Cambridge, MA, USA: Lean Enterprise Institute.

Vines, M. M., Dupler, A. E., Van Son, C. R., & Guido, G. W. (2014). Improving client and nurse satisfaction through the utilization of bedside report. Journal of Nurses in Professional Development, 30(4), 166-173; quiz E161-162. doi: 10.1097/nnd.0000000000000057