This is the fifth column reporting the results of a survey addressing nurses’ attitudes and perceptions regarding standardized nursing terminologies that was completed by the authors in the fall of 2011. Prior columns have examined the demographics of our respondents and their familiarity with the American Nurses Association (ANA) standardized nursing terminologies (Schwirian & Thede, 2012); educational preparation for using the terminologies (Thede & Schwirian, 2013b); users perception of confidence in using the terminologies (Thede & Schwirian, 2013c); and effects of documenting with standardized nursing terminologies (Thede & Schwirian, 2013a.)

In this column, we will report users’ opinions about the helpfulness of a terminology in actual clinical practice. The findings presented below are from those respondents who answered ‘yes’ to the following three questions about the terminology: (a) are you familiar with the terminology?, (b) have you used it in some way?, and (c) have you used this particular terminology in actual patient care?

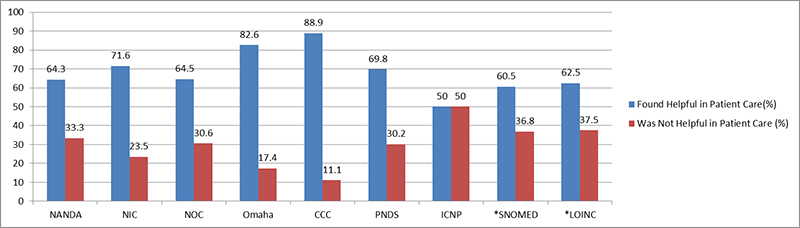

Table 1 and Figure 1 illustrate the percentage of clinical users of a terminology who found the terminology helpful in actual clinical practice.; With the exception of the International Classification of Nursing Practice (ICNP) terminology, for which there were only four responses, more than 60% of clinical users of the nursing-specific terminologies found them helpful in clinical patient care. The Clinical Care Classification (CCC) users and the Omaha System users gave the most positive responses as noted in Table 1. Users of the interdisciplinary terminologies, Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Code (LOINC) and Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine Clinical Terminology (SNOMED CT), had the least positive perceptions regarding the helpfulness of the terminology in clinical practice. For the nursing-specific terminologies, North American Nursing Diagnosis Association, International (NANDA-I) and the Nursing Outcomes Classification (NOC) had relatively high percentages of users who did not find the terminology helpful in clinical practice.

Table 1. Users Who Found a Terminology Useful in Clinical Practice

|

Used in patient care |

Found helpful |

||

|

Helpful (%) |

Not Helpful (%) |

||

|

NANDA |

249 |

160 (64.3) |

83 (33.3) |

|

NIC |

81 |

58 (71.6) |

19 (23.5) |

|

NOC |

62 |

40 (64.5) |

19 (30.6) |

|

Omaha |

46 |

38 (82.6) |

8 (17.4) |

|

CCC |

18 |

16 (88.9 |

2 (11.1) |

|

PNDS |

43 |

30 (69.8) |

13 (30.2) |

|

ICNP |

4 |

2 (50.0) |

2 (50.0) |

|

*SNOMED |

38 |

23 (60.5) |

14 (36.8) |

|

*LOINC |

24 |

15 (62.5) |

9 (37.5) |

*Interdisciplinary terminologies

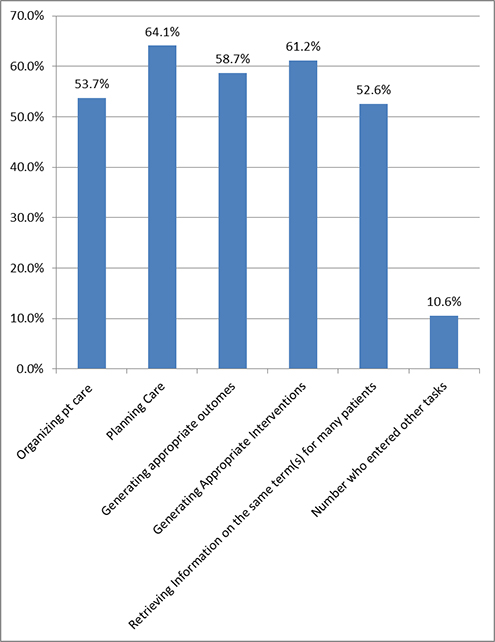

Figure 1. Useful in Clinical Practice

Tasks for Standardized Terminologies

Clinical users of a terminology who answered ‘yes’ to the question about whether a terminology was helpful in clinical practice were then asked, “In what ways was X (the specific terminology) helpful to you?” A list of possible choices followed (below). Participants could check as many options as they felt were relevant and could also add other options.

- Organizing patient care

- Planning care

- Generating appropriated outcomes

- Generating appropriate interventions

- Retrieving information on the same term for many patients

- Other (please specify) or comments

Table 2 reports the numbers of respondents who selected each task and the percentage of clinical users of that terminology who found it helpful in that area. The bottom line provides the overall average of the helpfulness of the terminologies for each task/option. If one looks at this data for all the terminologies, planning care (64/1%) was found to benefit most from terminology use while retrieving information was found to have the least benefit, followed closely by organizing patient care (53.7%). Because these terminologies have different foci, the percentages for each task may not be exactly comparable between the terminologies. For this reason, each terminology will be explored separately, along with some ‘free text’ tasks that respondents entered for that terminology.

Table 2. Tasks for Which a Standardized Terminology Is Helpful In Patient Care

|

Termin-ology |

Found helpful |

Organizing patient care |

Planning care |

Generating appropriate outcomes |

Generating appropriate interventions |

Retrieving information on the same term(s) for many patients? |

Number who entered other tasks |

|

NANDA |

160 |

91 (56.9) |

133 (83.1) |

105 (65.6) |

118 (73.8) |

51 (31.9) |

14 (8.8) |

|

NIC |

58 |

33 (56.9) |

47 (81.0) |

28 (48.3) |

49 (84.5) |

24 (41.4) |

6 (10.3) |

|

NOC |

40 |

20 (50.0) |

29 (72.5) |

34 (85.0) |

23 (57.5) |

18 (45.0) |

1 (2.5) |

|

Omaha |

38 |

26 (68.4) |

29 (76.3) |

25 (65.8) |

27 (71.1) |

23 (60.5) |

6 (15.8) |

|

CCC |

16 |

8 (50.0) |

15 (93.8) |

13 (81.3) |

14 (87.5) |

10 (62.5) |

1 (6.3) |

|

PNDS |

30 |

17 (56.7) |

19 (63.3) |

24 (80.0) |

24 (80.0) |

15 (50.0) |

1 (3.3) |

|

ICNP |

2 |

1 (50.0) |

1 (50.0) |

1 (50.0) |

1 (50.0) |

1 (50.0) |

0 (0.0) |

|

SNOMED |

23 |

11 (47.8) |

10 (43.5) |

9 (39.1) |

6 (26.1) |

12 (52.2) |

5 (21.7) |

|

LOINC |

15 |

7 (46.7) |

2 (13.3) |

2 (13.3) |

3 (20.0) |

12 (80.0) |

4 (26.7) |

|

Average |

23.8 (53.7) |

31.7 (64.1) |

26.8 (58.7) |

29.4 (61.2) |

18.4 (52.6) |

4.2 (10.6) |

|

Nursing Specific Terminologies

Most of the ANA recognized, standardized terminologies are nursing specific; that is, they have more in common with nursing than any of the other health disciplines. This does not mean that they cannot be used in other disciplines; rather it means that they address many specific nursing situations, not only the dependent functions of nursing, but also independent nursing functions.

North American Nursing Diagnosis Association - International

The North American Nursing Diagnosis Association- International (NANDA-I) was developed to allow nursing to identify and classify health problems within the domain of nursing (Jones, Lunney, Keenan, & Moorhead, 2010). Concomitant with this purpose were the goals of increasing the visibility of nursing, organizing nursing data, and allowing costs to be assigned to nursing. Since the first national meeting of NANDA-I in 1973, where 100 nursing diagnoses were identified and organized alphabetically, it has evolved to a taxonomy with 13 domains, 47 classes, and 205 diagnoses (NANDA, n.d.). It is intended to “communicate the professional judgments that nurses make every day to patients, colleagues, members of other disciplines, and the public” (NANDA-I, 2012, paragraph 2).

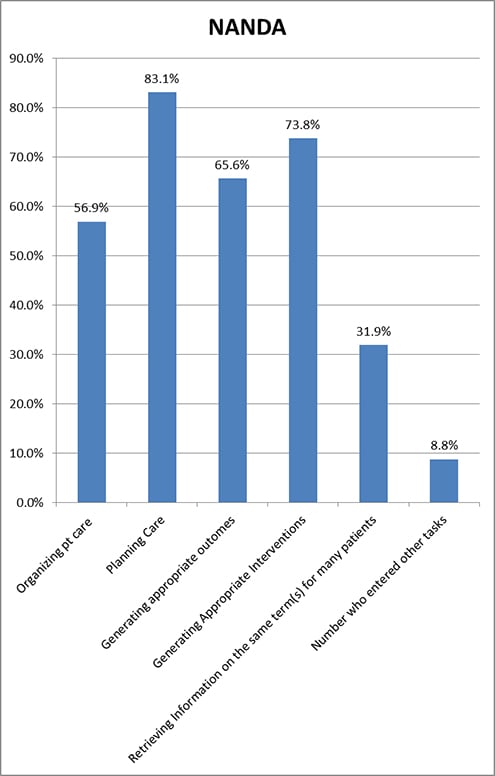

Figure 2. Tasks for Which NANDA-I Was Useful

Planning care was the area in which respondents who used NANDA-I in the clinical area found the terminology most useful; the next most useful task that NANDA-I users reported was generating appropriate interventions (See Figure 2 and Table 2). More than 50% of NANDA-I users found NANDA-I helpful for all the above the tasks, with the exception of retrieving information on the same term for many patients. Because few electronic records are set up to permit this retrieval, and there is no current push for nurses to look at the effects of clinical practice on a specific diagnosis, this is not surprising. What is encouraging is that 31.9% of NANDA-I clinical users did find the use of NANDA-I helpful in retrieving information.

Fourteen of the 160 users who found NANDA-I helpful in clinical practice entered tasks other than those listed. ‘Providing continuity of care,’ ‘prioritizing the needs of the patient,’ and ‘providing terminology to use during documentation,’ were three tasks entered as free text. One respondent noted that it assisted in communicating with other members of the care team, especially MDs. Another respondent stated, “It made me a deliberate, quality-outcome-focused provider.It made me less task oriented and more outcome oriented.” In this same vein another respondent wrote, “With NANDA, the evidence or literature supporting the defining characteristics is available and does help in identifying the outcomes to consider for measurement.” An educator added it was helpful in “…educating students to pay attention to cues and provide complete care to their patients.”

Nursing Intervention Classification

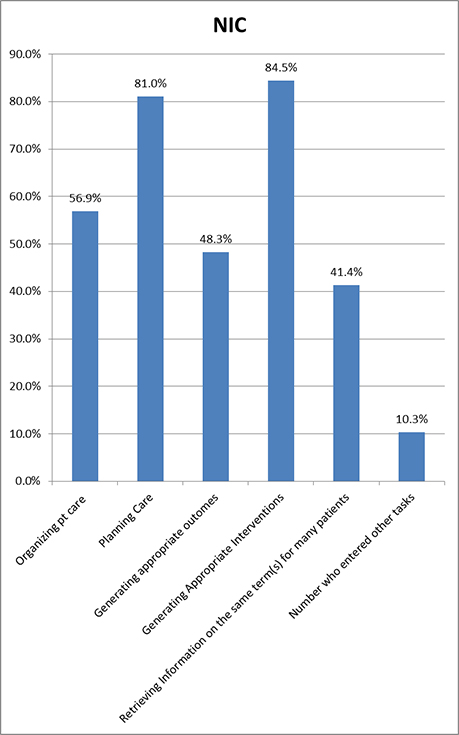

The Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC) is a comprehensive, research-based, standardized classification of nursing interventions (Center for Nursing Classification & Clinical Effectiveness, 2013). It classifies interventions, both independent and inter-dependent, and the nursing activities required to implement them. The NIC has 554 interventions that are grouped into seven domains and thirty classes. It is intended to be used as part of the planning process in creating a nursing care plan. As would be expected, respondents checked generating appropriate interventions (See Table 2 and Figure 3) as the task for which they found the terminology most useful; 81% found this terminology helpful in planning care. Only 41.4% found it helpful in retrieving information on the same term for many patients.

Figure 3. Tasks for Which NIC Was Useful

Clinical users of NIC found this terminology helpful in organizing patient care. They also believed that using this terminology enabled the details of care to be better explained and that it was especially useful for shift hand-offs. One educator stated, “Students benefitted by the cues toward the outcomes appropriate for some patients.”

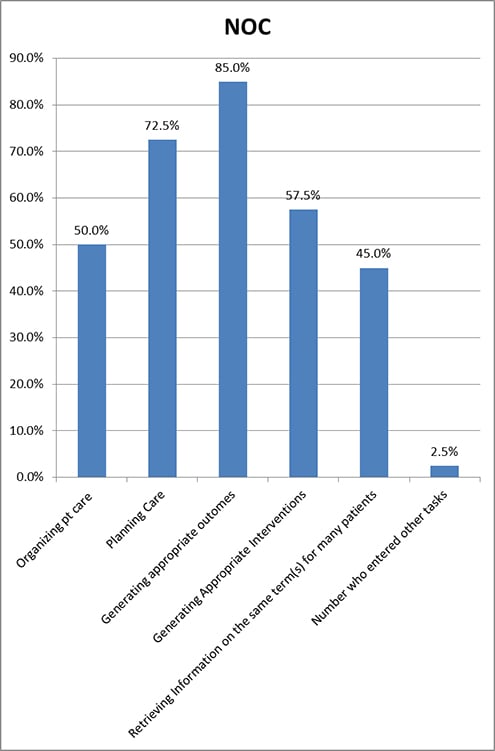

Nursing Outcomes Classification

The nursing outcomes classification (NOC) is intended to provide a measurable way to evaluate the effect of nursing interventions on patient progress (Lu, Park, Ucharattana, Konicek, & Delaney, 2007). It consists of 490 outcomes with a list of indicators to evaluate the patient status (College of Nursing University of Iowa, 2013). Interestingly, the only extra task for NOC that was entered was ‘use as an educational tool for nursing students.’ Appropriately, 85.0% of users found that the most useful task for NOC in clinical care was generating appropriate outcomes; the next most useful task was help in planning care (See Table 2 and Figure 4).

Figure 4. Tasks for Which NOC Was Useful

NANDA-I, NIC, & NOC (NNN)

Each of the above three terminologies addresses only one of the three nursing elements needed for full planning and documentation. To provide terminology to document nursing problems, interventions, and outcomes it is necessary for NANDA-I, NIC, & NOC to be used together. For this reason, the three may be referred to as NNN. However, of the 290 respondents who reported that they were familiar with all three terminologies, only 109 of these used all three in any way, and only 49 reported using all three in clinical patient care.

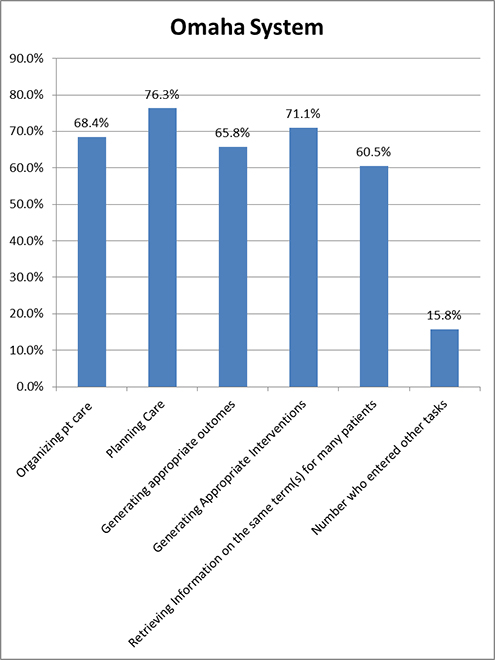

OMAHA System

The Omaha System was originally devised as a way for home healthcare nurses to document their care. Like the other nursing-specific terminologies, with the exception of the NNN terminologies, the Omaha System includes, within it, terminology for nursing diagnosis, interventions, and outcomes. Although differences between these tasks were small for users of the Omaha System, the task for which they found it most helpful was planning care (See Table 2 and Figure 5). Individual respondents also found it helpful in publications and in communicating between disciplines. One participant wrote, “Does not address Lactation AT ALL! Had to maneuver the system to force it to work.” This may be a statement that is applicable to other terminologies, particularly if there is a forced response from a limited list.

Figure 5. Tasks for Which the Omaha System Was Useful

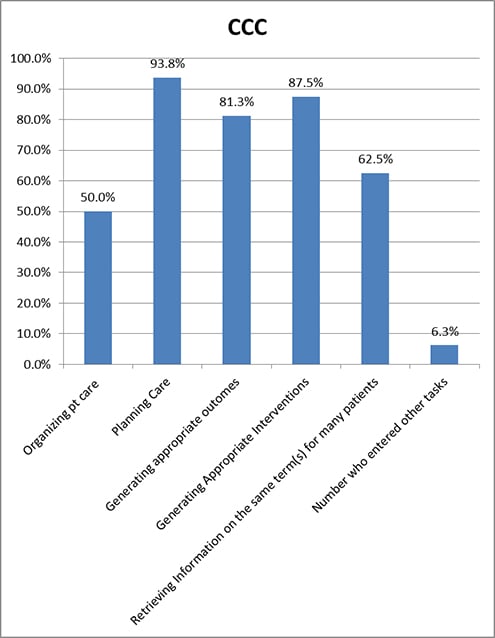

Clinical Care Classification

The Clinical Care Classification (CCC), originally named the Home Health Care Classification, was designed for electronic coding to predict home healthcare use for Medicare patients (Saba, 2012c). It has since evolved to be a full clinical care terminology and has been integrated into some electronic healthcare systems. There are 176 nursing diagnoses and 201 ‘Core Interventions’ in the CCC (Saba, 2012a). Outcome is based on the original nursing diagnosis, and is documented as improved, stabilized, or deteriorated (Saba, 2012b). Users of the CCC found it very helpful in planning care and least helpful in organizing patient care (50.0%) (See Table 2 and Figure 6). One respondent, in discussing the CCC system, stated, “Easy to build based on the nursing assessment. Easy to set triggers and reminders.”

Figure 6. Tasks for Which the CCC Was Useful

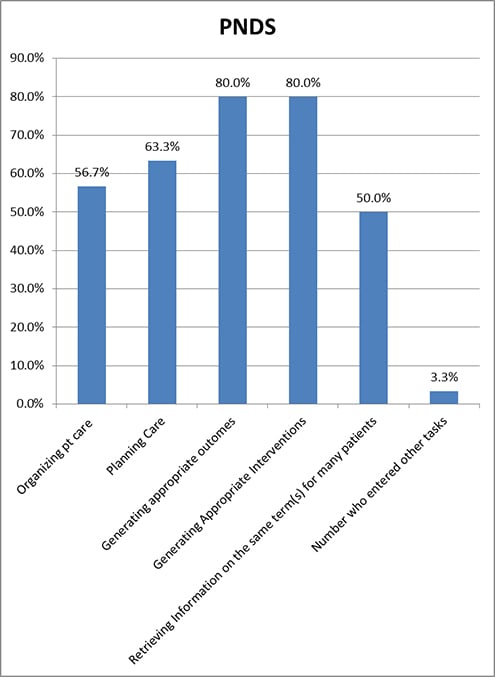

Perioperative Nursing Data Set

The Perioperative Nursing Data Set (PNDS) is intended to make visible to administrators the patient problems that perioperative nurses manage. It includes the entire surgical patient experience from preadmission to discharge; it consists of 93 nursing diagnosis, 151 nursing interventions, and 38 nurse sensitive patient outcomes (United States (U.S.) National Library of Medicine, 2012a). Eighty percent of users found this terminology helpful for both generating appropriate interventions and outcomes (See Table 2 and Figure 7). One respondent added, “Helpful in providing consistent documentation.”

Figure 7. Tasks for Which the PNDS Was Useful

International Classification of Nursing Practice

Only two of the four users found the International Classification of Nursing Practice (ICNP) useful; all five categories were found helpful by one of the two users (See Table 2). The U.S. National Library of Medicine (2012b, paragraph 3) states, “The ICNP terminology was developed to establish an international standard for the description and comparison of nursing practice, and to facilitate the development of cross-mapping between local terms and other terminologies.” This terminology was originally a reference terminology, in that it was not originally designed as an interface terminology, or one that would be used in direct documentation. However, the International Council of Nursing (ICN) has developed, and is continuing to develop catalogues that have terms for diagnoses, outcomes, and interventions based on the ICNP concepts; these terms can be used to document patient care (International Council of Nurses, 2013).

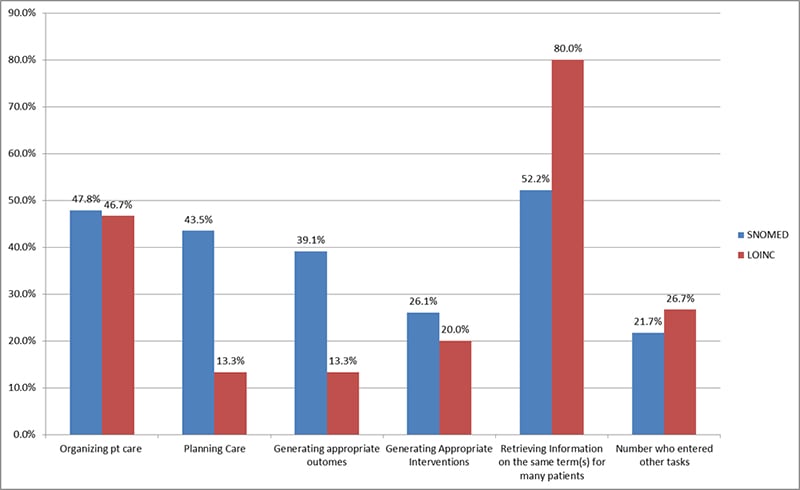

Interdisciplinary Terminologies

The ANA recognized three interdisciplinary terminologies, the Alternative Billing Codes (ABC), SNOMED CT, and LOINC. The ABC codes are not used in direct clinical care and are not addressed here. There are other standardized, healthcare terminologies, but our survey studied only the ANA recognized, standardized terminologies. We will discuss the SNOMED CT and LOINC terminologies below.

Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine - Clinical Terms

The Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine--Clinical Terms® (SNOMED CT) was also not designed to be an interface terminology. However, there is a nursing subset that is designed to facilitate the use of the SNOMED® in the Electronic Health Record (EHR) for coding nursing problems and enabling meaningful use (National Library of Medicine, 2011).The lowest category of usefulness in clinical care for SNOMED® users was generating interventions while the highest was retrieving information. This is the only category that SNOMED® users rated above 50% (See Table 2 and Figure 8). It is not known whether the users who responded to these questions about using SNOMED® were using the nursing subset. The statement, “Compliance: ultimately important for clinical reporting,” was entered as helpful in the clinical use of SNOMED®.

Figure 8. Tasks for Which SNOMED & LOINC Were Useful

Logical Observation Identifiers, Names, and Codes

Although originally designed for communicating laboratory assessments, the purpose of the Logical Observation Identifiers, Names, and Codes (LOINC) has expanded to include the coding of assessment data for the EHR. These measures include vital signs and assessments from standardized nursing terminologies (Matney, Bakken, & Huff, 2003). LOINC users gave the highest percentage of any of the terminologies to the choice of ‘retrieving information on the same term for many patients.’ The next highest terminology for this category was for SNOMED®.

Conclusions

We found that the task with the highest average regarding helpfulness of standardized terminologies was the task of planning care. This supports Carrington (2012) who studied the strength and limitations of NANDA-I, NIC, & NOC in the ERH and found that planning care was one of the useful tasks facilitated by these terminologies. Generating appropriate interventions and generating appropriate outcomes were selected as the next tasks that were most facilitated by these terminologies (Table 1 and Figure 9). However, given the different foci of the terminologies, drawing conclusions from the overall averages is suspect, particularly in the area of retrieving information using the same term for many patients.

Figure 9. Averages for Usefulness in Tasks for All the Terminologies

Drawing conclusions from the results for the ICNP, SNOMED®, and LOINC should also be done with reservations. Only four users of the ICNP reported using it clinically and only two of these found it helpful. It is quite possible that the categories listed for SNOMED® and LOINC were inappropriate for these terminologies and may have created tunnel vision in the respondents. An indication of this can be seen in some of the free text comments for LOINC. Users stated that LOINC was useful in “matching terms across different agency systems,” “documenting assessments such as vital signs and lab values,” “making data shareable with other providers, e.g., facilitating interoperability,” and “managing medication charges and interfaces.” One SNOMED® user seemed confused and entered that it assisted with “pathology results” and “scheduling surgeries, patient education and follow-up, and automated electronic retrieval of information and educational materials.” Additionally, these interdisciplinary terminologies are not well known in nursing; although unbeknownst to nurses, some of their documentation may be automatically coded behind the scenes to one or both of these terminologies.

In interpreting these results, it is important to keep in mind that they are the result of an Internet Survey, with the usual, concomitant, confounding factors, such as self-selection of respondents. The decision to require answers to only the first question about a terminology led many participants to skip one, some, or all of the questions pertaining to their (a) familiarity with the terminology, (b) using it in any way, (c) using it in actual patient care, or (d) using it to document care, but to then answer subsequent questions. We choose to select only responses from those who committed to answer all these questions, which may or may not have skewed the results.

Authors

Linda Thede, PhD, RN-BC

Email: lqthede@roadrunner.com

Linda Thede is currently the editor of CIN Plus, a 12 page insert in CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing. She has served as course mentor for informatics for St. Joseph’s College, Excelsior College, and Thomas Edison College. Prior to this she was an Assistant Professor in the School of Nursing at Kent State University where she participated in numerous University Committees studying and implementing computer uses and distance education. At Kent she taught nursing informatics and assisted the faculty in the use of technology for many uses including databases. She was a cofounder of the Informatics Nurses of Ohio, and served as its first president. She is certified in Informatics and has published a book, Informatics and Nursing, which is in its fourth edition. She founded the second listserv used in nursing, Gradnrse, which she merged with NurseRes, a listserv that she started with the support of the Midwest Nursing Research Society and has been listed as a pioneer in nursing informatics by the AMIA Nursing Informatics History Committee.

Patricia M. Schwirian, PhD, RN

Email: schwirian.1@osu.edu

Dr. Pat Schwirian is Professor Emeritus of Nursing at The Ohio State University (OSU), Columbus, Ohio, and an Adjunct Professor in the College of Information Science and Technology at Drexel University (Philadelphia, PA) where she teaches a graduate course in Nursing Informatics. Patricia became one of the initial adopters of online instruction while teaching in The OSU College of Nursing; she currently teaches an online course in Gerontology for The OSU College of Medicine. Dr. Schwirian was very actively involved in the ‘early days’ of Nursing Informatics, serving as the first Research Editor of the journal, Computers in Nursing (now CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing), and has been named as a Pioneer in Nursing Informatics by the National Library of Medicine & American Medical Informatics Association. She earned her BS in Science/Math Education at Illinois State University, Normal, IL; her BS in Nursing at Capital University in Columbus, OH; her MS in Science Education at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, and her PhD in Science Education at The Ohio State University. In addition she has completed a post-doctoral fellowship in Medical Sociology at The Ohio State University.

References

Carrington, J. M. (2012). The usefulness of nursing languages to communicate a clinical event. Computers Informatics Nursing, 30(2), 82-88. doi: 10.1097/NCN.0b013e318224b338

Center for Nursing Classification & Clinical Effectiveness. (2013). CNC - overview: Nursing interventions classification (NIC). Retrieved from www.nursing.uiowa.edu/cncce/nursing-interventions-classification-overview

College of Nursing, University of Iowa. (2013). Overview: Nursing outcomes classification (NOC) Retrieved from http://www.nursing.uiowa.edu/cncce/nursing-outcomes-classification-overview

International Council of Nurses. (2013). Guidelines for ICNP Catalogue Development Retrieved from www.icn.ch/pillarsprograms/icnpr-catalogues/

Jones, D., Lunney, M., Keenan, G., & Moorhead, S. (2010). Standardized nursing languages Annual Review of Nursing Research, 28, 253-294.

Lu, D. F., Park, H. T., Ucharattana, P., Konicek, D., & Delaney, C. (2007). Nursing outcomes classification in the systematized nomenclature of medicine clinical terms: A cross-mapping validation. CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 25(3), 159-170.

Matney, S., Bakken, S., & Huff, S. M. (2003). Representing nursing assessments in clinical information systems using the logical observation identifiers, names, and codes database. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 36(4-5), 287-293.

North American Nursing Diagnosis Association- International (NANDA-I). (2012). About us. Retrieved from www.nanda.org/AboutUs.aspx

NANDA (n.d). In Wikipedia. Retrieved March 5, 2014, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/NANDA_International

National Library of Medicine. (2011). CORE problem list subset of SNOMED CT® now available Retrievedfrom www.nlm.nih.gov/news/snomed_core_200907.html

Saba, V. K. (2012a). About. Retrieved from http://www.sabacare.com/About/?PHPSESSID=b9e97459af41b2c80d194d7434aa7800

Saba, V. K. (2012b). Nursing outcomes. Retrieved from www.sabacare.com/Outcomes/

Saba, V. K. (2012c). Background Retrieved from www.sabacare.com/About/Background.html

Schwirian, P., & Thede, L. (2012, May 21). Informatics: The standardized nursing terminologies: A national survey of nurses’ experience and attitudes—SURVEY II: Participants, familiarity and information sources. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 17(2). doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol17No2InfoCol01

Thede, L. Q., & Schwirian, P., M. (2013a, Dec 16). Informatics: The standardized nursing terminologies: A national survey of nurses’ experience and attitudes—SURVEY II: Participants’ documentation use of standardized nursing terminologies. [Electronic version at http://www.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/ANAMarketplace/ANAPeriodicals/OJIN/Columns/Informatics/Documentation-Use-of-Standardized-Nursing-Terminologies.html.] Online Journal or Issues in Nursing, 19(1). doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol19No01InfoCol01

Thede, L. Q., & Schwirian, P. M. (2013b, March 25). Informatics: The standardized nursing terminologies: A national survey of nurses’ experience and attitudes —SURVEY II: Participants’ education for the use of standardized nursing terminology “labels.” [Electronic version at www.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/ANAMarketplace/ANAPeriodicals/OJIN/TableofContents/Vol-18-2013/No2-May-2013/Education-for-the-Use-of-Standardized-Nursing-Terminology-Col-1.html]. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 18(2). doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol18No02InfoCol01

Thede, L. Q., & Schwirian, P. (2013c, March 25). Informatics: The standardized nursing terminologies: A national survey of nurses’ experience and attitudes—SURVEY II: Participants’ perception of comfort in the use of standardized nursing terminology "labels." [Electronic www.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/ANAMarketplace/ANAPeriodicals/OJIN/TableofContents/Vol-18-2013/No2-May-2013/Education-for-the-Use-of-Standardized-Nursing-Terminology-Col-1.html]. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 18(2). doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol18No02InfoCol02

US National Library of Medicine. (2012a). 2011AA perioperative nursing data set source information Retrieved from www.nlm.nih.gov/research/umls/sourcereleasedocs/current/PNDS/

US National Library of Medicine. (2012b). 2011AB international classification for nursing practice (ICNP) source information Retrieved from www.nlm.nih.gov/research/umls/sourcereleasedocs/current/ICNP/