The strongest predictor of nurse job dissatisfaction and intent to leave is that of stress in the practice environment. Good communication, control over practice, decision making at the bedside, teamwork, and nurse empowerment have been found to increase nurse satisfaction and decrease turnover. In this article we share our experience of developing a rapid-design process to change the approach to performance improvement so as to increase engagement, empowerment, effectiveness, and the quality of the professional practice environment. Meal and non-meal breaks were identified as the target area for improvement. Qualitative and quantitative data support the success of this project. We begin this article with a review of literature related to work environment and retention and a presentation of the frameworks used to improve the work environment, specifically Maslow’s theory of the Hierarchy of Inborn Needs and the National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators™ Survey. We then describe our performance improvement project and share our conclusion and recommendations.

Keywords: Hospital, nurse retention, engagement, satisfaction, work environment, NDNQI® practice environment, intent to stay, Maslow’s hierarchy, meal breaks, rapid-design process

The strongest predictor of nurse job dissatisfaction and intent to leave a job is stress in the practice environment (Zangaro & Soeken, 2007). The varied causes of job stress include patient acuity, work schedules, poor physician-nurse interactions, new technology, staff shortages, unpredictable workload or workflow, and the perception that the care provided is unsafe (Bowles & Candela, 2005; Leurer, Donnelly, & Domm, 2007; Shader, Broome, Broome, West, & Nash, 2001; Zangaro & Soeken, 2007).

In contrast, a healthy practice environment is characterized by an engaged nursing staff who exercise control over nursing-related issues, ground their practice in the evidence, and collaborate with colleagues from diverse disciplines (Kramer & Schmalenberg, 2008). Such an environment is associated with favorable clinical outcomes and a stable, satisfied workforce (Gallup, 2005). Good communication, control over practice, decision making at the bedside, teamwork, and nurse empowerment are aspects of the practice environment that increase satisfaction and decrease nurse turnover (DiMiglio et al., 2005; Heath, Johanson, & Blake 2003; Kalisch, Curley, & Stefanov, 2007).

Although much can be learned from experiences reported by others, care must be taken to critically assess perceptions of nurses at each individual facility, and each unit within that facility, to determine which practice environment improvement strategies would be most effective in a given situation. The National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators ™ (NDNQI®) 2009 RN Survey with Practice Environment Scale, henceforth called the NDNQI 2009 RN Survey with Practice Environment Scale, can help individualize practice improvement interventions to a given unit.

We will begin this article with a review of literature related to work environment and retention and a presentation of the frameworks used to improve the work environment, specifically Maslow’s theory of the Hierarchy of Inborn Needs and the National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators™ Survey. We then describe our performance improvement project and share our conclusion and recommendations.

Frameworks for Improving the Work Environment

This section will describe two frameworks that we found helpful for improving the work environment. These frameworks included the National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators ™ Survey with Practice Environment Scale and Maslow’s theory of the Hierarchy of Inborn Needs. Without a framework by which to approach practice environment improvements, the thousands of potential improvement strategies presented in the literature can be overwhelming. Therefore, we used Maslow’s theoretical framework described below, along with survey data collected via the NDNQI 2009 RN Survey with Practice Environment Scale, to help focus our efforts and identify opportunities and strategies for improvement.

Maslow’s Theoretical Framework

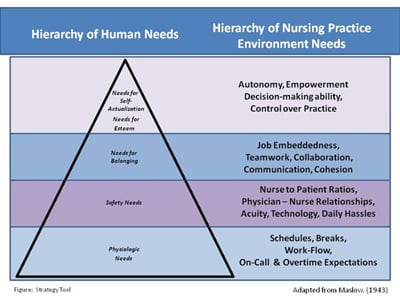

In the mid 1940s Abraham Maslow developed his theory of the Hierarchy of Inborn Needs (Maslow, 1943). Maslow conceptualized human needs as a pyramid with five levels in ascending order, ranging from physiologic needs at the base, through safety, belonging, and esteem, to self-actualization at the apex of the pyramid. Maslow posited that people are innately motivated toward psychological growth and self-development. He explained that humans work to achieve unmet needs at the lower levels before attending to those at the higher levels. As each lower-level need is satisfied, the next higher need occupies one’s main attention until it is satisfied. The highest level need, self-actualization, is that of “becoming all that one is capable of becoming in terms of talents, skills and abilities” (Hoffman, 2008, p. 36). Applying this model to nursing practice suggests that when nurses do not feel that their basic practice environment needs are being met, they will be less motivated and less likely to progress to the higher-level functions (Chinnis, Summers, Doer, Paulson, & Davis, 2001). We developed the Figure to show the correspondence between the levels of Maslow’s hierarchy and the practice environment needs that nurses face every day. We combined the needs for esteem and self-actualization because of the overlap of these needs as related to the practice environment.

We believe that patients want the assurance that they are being cared for by a nurse who is utilizing the best practices possible. This includes the integration of evidence-based, decision-making models into their daily practice. In this performance improvement study we utilized both an established theoretical framework and an established, systematic process for collecting data to guide our practice improvement intervention.

The National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators ™ (NDNQI) 2009 RN Survey with Practice Environment Scale

Within NDNQI there are three survey options. The option we chose to use was the NDNQI® RN 2009 Survey with Practice Environment Scale as endorsed by the National Quality Forum. It is a reliable and valid tool that measures the perceptions of nurses with respect to their practice environment (Montalvo, 2007). Each year thousands of nurses across the country participate in this survey, thus providing strong national benchmarking in addition to unit- and facility-specific comparisons. This tool is based on the RN Survey Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index which measures five parameters: nurse participation in hospital affairs, nursing foundations for quality care, nurse manager ability and support of nurses, staffing and resource adequacy, and collegial nurse-physician relationships (Lake, 2002). The tool also addresses work context items related to job plans and quality of care within the practice environment (Aiken, Clarke, & Sloane, 2002) and measures demographic data and job enjoyment.

Review of Literature

A literature search related to work environment and nurse retention was conducted in the fall of 2008 using PubMed and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL). Mesh terms included: nurses, retention, hospital, work environment, career mobility, personnel turnover, and intent to stay. These two searches identified 2,438 citations related to environment and retention. The search was refined by limiting studies to those that were reported in English and published no earlier than the year 2000. Studies that were unpublished doctoral dissertations; duplications from the two databases; conducted on a small subset of nurses outside of the United States; or not related to nurses at the bedside in an acute care setting, including long-term or home-care settings, were eliminated. After completing a title and abstract review of the remaining 535 references, we selected 171 for full-text consideration.

This review of the literature helped us identify various levels of practice environment needs related to nurse retention and realize that there are many reasons why bedside nurses leave their jobs. These reasons are complex and varied, and no single intervention to the practice environment will improve retention of bedside nurses for all hospitals (Institute of Medicine, 2004). However, in reviewing the literature we did identify common themes that suggested why nurses leave a given workplace and offered interventions that may promote retention.

The practice environment levels of needs that we identified corresponded with Maslow’s framework, including nurses’ need to feel safe in their environment and provide safe care for their patients, to have a sense of belonging to their organization, and to feel empowered to do what they believe they should be doing. Maslow’s theory suggests that once nurses’ basic needs are met, their focus will shift toward achieving higher level needs, including their sense of belonging, self-esteem, and self-actualization.

Inadequate staffing and daily hassles raise the stress level of nurses and drive many nurses to leave the profession (American Association of Colleges of Nursing [AACN] Nursing Shortage Fact Sheet, 2007). Verbal abuse and disruptive behavior on the part of physicians have also been associated with nurses’ job dissatisfaction (Rosenstein, 2002). Daily ‘hassles,’ such as ‘hunting and gathering activities,’ deter nurses from meaningful patient care (Beaudoin & Edgar, 2003); an example of these activities is that of taking the time to find medications and supplies. These basic stressors can threaten patient safety and adversely affect the nurses’ perceptions of their practice environment. These stressors relate to the lower practice environment levels of need. Nurse leaders are advised to address first the basic needs of nurses for adequate staffing and ability to provide safe nursing care (Cline, Reilly, & Moore, 2003).

The business management literature establishes job embeddedness (a higher level of practice environment need) as a predictor of nurse retention. Holtom and O’Neill (2004) have explained that job embeddedness includes a variety of parameters that influence employee retention. These parameters include the extent to which nurses’ jobs and the community in which the nurses live are similar to, or fit with, other aspects of their life; the extent to which the nurses have links to other people and activities; and the ease with which the links can be broken. They have concluded that embeddedness in the organization is influenced by embeddedness in the social community of both the home and the practice environment.

Much of the literature on nurse empowerment is based on Kanter’s theoretical framework of structural empowerment (Kanter, 1993; Laschinger, Almost, & Tuer-Hodes, 2003). Kanter conceptualized power as the ability to tap into the resources needed to get things done. When power is unavailable, work is impossible (Laschinger et al., 2003). Empowerment is linked to two dimensions of decision making in the nursing practice environment, namely the perception of autonomy and the perception of participative management in the work setting (Laschinger et al., 2003). Perceptions of empowerment increase when nurses perceive they have control over practice (Kramer et al., 2008).

We propose that if nurse leaders first embrace a Maslow-type emphasis on meeting nurses’ basic practice environment needs, they subsequently will be more successful in meeting nurses’ higher level needs, such as meaningful engagement and higher level performance. We further propose that failure to attend to basic needs may contribute to nurses’ apathy and distrust of leadership, resulting in job discontent, decreased quality of care, and ultimately resignation from the institution.

The Performance Improvement Project

Our performance improvement project included the following three goals

- To administer the NDNQI ® 2009 RN Survey with Practice Environment Scale throughout the institution

- To create for bedside nurses a toolkit that would enable them to interpret and analyze their unit survey results

- To pilot an intervention designed to improve the nurses’ perception of their practice environment and promote delivery of safe patient care

In this section we will describe how we implemented our practice improvement intervention and the outcomes of this intervention; we will also discuss our findings in relation to the literature and our organization.

Implementation

Our facility is a 300 bed, community medical center located on a suburban campus outside a large metropolitan area in the Mid-Atlantic region. Approximately 1200 nurses are employed; 900 provide direct patient care. Our institution does not require Institutional Review Board (IRB) review for quality improvement projects. The proposal was submitted to the IRB for review and was deemed a quality improvement project, therefore it was exempt from further review. The project had three phases. Phase I involved administering the NDNQI® 2009 RN Survey with Practice Environment Scale to all bedside nurses. Phase II utilized the rapid-design process to develop and implement a tool kit that would guide staff nurses in analyzing and interpreting the survey results for their nursing unit, with the goal of improving the practice environment. Phase III evaluated the outcomes of this pilot project.

Phase I: Administration of the NDNQI®. The project began with the administration of the on-line NDNQI® 2009 RN Survey with Practice Environment Scale to obtain a baseline measurement from all bedside nurses on all inpatient nursing units. All NDNQI® guidelines for implementation were strictly adhered to. Executive support was obtained and a communication strategy was developed. This included ongoing communication with the Nursing Leadership Council and also house-wide divisional and unit-level practice councils. 513 nurses responded to the survey. Sixty-nine percent were full-time Registered Nurses (RNs), 23% were part-time RNs, and 8% were per-diem RNs. The facility employs no LPNs. No assistive staff participated in the survey. An overall response rate of 62% was obtained.

Phase II: Performance improvement in the newborn nursery unit. Whereas the NDNQI® measurement was administered throughout the organization in Phase I, Phase II was initiated on a single patient care unit so as to promote full participation of this staff in the development, administration, and refinement of the tools to be used later on all nursing units. The pilot unit chosen for this project was the Newborn Nursery. This decision was based on the collaborative relationship between ourselves, the manager, and the staff. The Newborn Nursery has an average daily census of 31 newborns, and employs 35 registered nurses. Seventeen of these nurses have been prepared at the baccalaureate degree level in nursing, ten at the associate degree level, and eight at the diploma level. Ten of the nurses hold Low Risk Neonatal Certification and four are Lactation Specialists.

A steering committee of interested nurses in the Newborn Nursery was formed to coordinate all activities related to this pilot study. Participants included one day-shift charge nurse and three bedside nurses (2 from day shift and 1 from night shift). These nurses comprised 10% of the unit staff. Two of these nurses were members of the institution’s unit-based practice council.

Analysis of the NDNQI® 2009 RN Survey with Practice Environment Scale produced a report which was more than 30 pages in length. While this report was clear and comprehensive to the Unit Steering Committees members, it would have required considerable staff time if all nurses were to learn to read and interpret the data. This would not have been the best use of staff time. Members of the Steering Committee (henceforth called the Committee) created and refined three tools to guide nurses in reading the findings and discussing, as a team, their unit-level data.

...The Strategy Tool, was developed to help staff nurses use Maslow’s theoretical framework to prioritize the opportunities to improve performance... The first tool, The Discussion Guide, was developed to summarize the data and to focus the discussion about the unit’s unique strengths and weaknesses. The second tool, The Strategy Tool, was developed to help staff nurses use Maslow’s theoretical framework to prioritize the opportunities to improve performance based on the Discussion Guide. This tool arranged the various levels of practice environment needs described in our literature review in a hierarchical fashion to guide in determining which concerns of the nurses would be most appropriate to address first (See Figure). The last tool in the toolkit, The Analysis Packet, explained how to analyze the NDNQI® data.

|

| (View larger version of the Figure and Table available in pdf here) |

The Committee identified the most significant opportunities for improvement of their unit to be related to Job Enjoyment and the Perceived Quality of Care. The Committee brainstormed potential causes for low scores in these two areas. The Committee posted on the bulletin board a list of possible causes for the low scores in these areas, along with potential interventions, such as improving teamwork between nurses and ancillary staff, improving communication between shifts, developing clearer guidelines surrounding assignments and floating, and improving the ability of the nurse to take breaks during their shift. The Committee sought input from the staff nurses.

The Committee then analyzed the information provided by the nurses and identified that the most pressing concern was the staff members’ inability to take meal and non-meal breaks. The Committee then analyzed the information provided by the nurses and identified that the most pressing concern was the staff members’ inability to take meal and non-meal breaks. The Committee found this to be a basic practice environment need located at the bottom of the hierarchy (See Figure), a need of importance to the unit staff, patient safety, and the practice environment.

Next guidelines were created that clearly outlined how breaks were going to be handled on all shifts. The Committee asked the nurse manager and charge nurses to meet with them to help develop these guidelines and to gain their support for the guidelines. The Committee also developed a log so that the charge nurses could track who took breaks and the duration of each break. A race car theme, with the catch phrase “we brake for breaks!,” was decided upon and Kickoff Parties, with food provided for each break period, were held to stimulate interest in this performance improvement project. Staff were introduced to the specific guidelines during their staff meetings; reminders were a part of every shift report. In keeping with rapid-design process, ongoing verbal feedback was solicited during manager and educator rounds; and written feedback was encouraged via a poster hanging in the unit. Every two weeks the group decided upon necessary changes to the guidelines based on the comments and responses of the nursing staff. Three cycles of improvement were completed before the post test was administered.

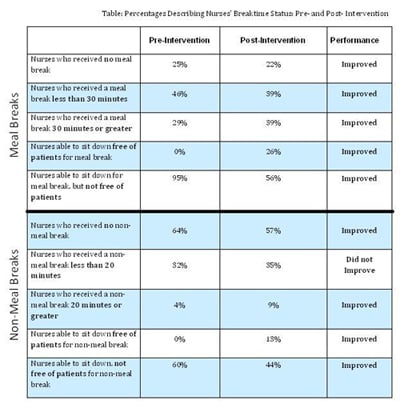

Every two weeks the group decided upon necessary changes to the guidelines based on the comments and responses of the nursing staff. Phase III: Evaluation. The NDNQI 2009 RN Survey with Practice Environment Scale served as the pre-intervention test. The single meal/non-meal item was repeated, with permission, in survey monkey format, as the post-intervention test. Twenty-three nurses participated in the post test. Data were categorized for “meal breaks” according to the NDNQI 2009 RN Survey response options: no break, less than 30 minutes, or equal to or greater than 30 minutes. “Non-meal breaks” were categorized as: none, less than 20 minutes, or equal to or greater than 20 minutes. Data were collected in the same categories as the original NDNQI® baseline measure. An additional survey was also distributed to members of this pilot unit Steering Committee to evaluate the approach and the tools used to facilitate the performance improvement process. The last question on both of the surveys was an open-ended question encouraging nurses to share their experiences of planning and/or participating in the intervention.

Findings

The quantitative findings from this performance improvement study are presented in the Table and discussed below. A comparison of the pre- and post-intervention implementation revealed that:

- At baseline nurses on the pilot unit frequently did not take breaks (25%).

- The number of nurses who took a meal break lasting 30 minutes or longer increased from 29% to 39%.

- The number of nurses unable to take any meal breaks during their shift decreased from 25% to 22%.

- The number of nurses able to sit down free of patient care responsibility for meal breaks increased from 0% to 26%.

Additionally, 100% of the steering committee identified the toolkit and rapid-design process as "Very Helpful."

|

| (View larger version of the Figure and Table available in pdf here) |

These nurses had indeed moved in the direction of attending more diligently to their personal needs and the safety of their patients by taking seriously the importance of adequate break times. Comments indicated that some nurses remained reluctant to leave their patients to take a break, or to call upon their equally busy colleagues to “double their patient load” so as to cover for them while on a break. In general these bedside nurses felt empowered by their participation. One nurse stated it was “exciting to be part of making a difference” on their unit. Another noted that it was “good to be part of the solution rather than stating issues but seeing no change.” The nurses considered the tools to be very helpful in addressing the need for adequate break times.

...more staff had a break that was free of patient care responsibilities post intervention. The first two aims of the project were clearly achieved. The third aim was partially achieved in that all indicators showed improvement except the ‘less than 20 minute non-meal break indicator.’ Although the number of nurses receiving non-meal breaks increased and the number who received a non-meal break of a full 20 minutes increased (both indicating improvement), the number of nurses receiving non-meal breaks that lasted less than the full 20 minutes also increased. The fact that the number of nurses receiving non-meal breaks of less than 20 minutes increased might have been due to the fact that post intervention, there were fewer nurses who indicated they had not received any non-meal break. These nurses who were currently not receiving any non-meal breaks might have ‘moved into’ the category of those who received a non-meal break, but this break was less than a 20 minute break. The bottom line is that regardless of the duration of the break, more staff had a break that was free of patient care responsibilities post intervention.

Steering Committee members and the leadership team of the pilot unit described the tool kit and the rapid-design process as invaluable in disseminating and responding to the NDNQI® data. Requests from other units to use the tools and replicate the performance improvement process further validated the usefulness of both. For example, the Labor and Delivery Practice Council implemented bedside report and the Surgical Intensive Care Unit implemented a project to improve physician-nurse collaboration.

Discussion

It was observed that some nurses were reluctant to leave their responsibilities and take a break. Some preferred to take no break at all. Others preferred to keep their phones with them in order to manage simple questions or coordinate the care of their patients. This staff reluctance to take a break is consistent with the literature (Hughes & Rogers, 2004; Scott, Hofmeister, Rogness, & Rogers, 2010). However, without a break, concentration and performance are impaired (Hughes & Rogers, 2004).

[To stimulate interest] a race car theme, with the catch phrase “we brake for breaks!,” was decided upon... One nurse manager reported in the literature her experience of attempting to change the nursing culture on her unit through a ‘break initiative’ using funding provided by the Robert Woods Johnson Foundation, Transforming Care at the Bedside (TCAB) Project. Staff nurses were encouraged to combine their meal and non-meal breaks to take a full-hour, off-unit respite. On this unit the major barrier identified was not in providing coverage, but rather in the nurses’ own resistance to take a break (Stefancyk, 2009). Once the culture shift related to this TCAB project occurred, and nurses were taking their hour-long break, they reported returning as if they were just arriving for the day, refreshed and ready to work. Interestingly, applying our Maslow-based Strategy Tool to the findings of this TCAB project, we noted that improvement in meeting the need for breaks (a physiologic need) facilitated improvement in higher level needs. Stefancyk (2009) shared that these nurses reported a greater sense of camaraderie, community, and teamwork amongst the staff on this unit as they worked to implement their hour-long break initiative.

In the past performance improvement activities at our institution were conducted in a top-down, hierarchical fashion. Institutional leaders identified which indicators would be measured and assumed the responsibility for data collection. A select group of nurses conducted audits, reviewed charts, and coordinated performance improvement activities. Bedside nurses were rarely involved in the process. This top-down approach provided for efficiency and control in the performance improvement process, but it did not engage staff or engender support for the projects. Although our bedside nurses, being new to the process of analyzing the NDNQI® did need support as they analyzed their unit data, the tool kit and guidance from nurse managers and educators provided the support they needed as they learned the process of analyzing their NDNQI® data.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The rapid-design process allowed bedside nurses to give ongoing feedback and see change occur based on that feedback.This kept the bedside nurses engaged in and supportive of this project. This article has described a successful performance improvement project that can increase nurse retention. Nurses found participation in this project to be an empowering experience. Bedside nurses managed the entire performance improvement initiative, including the data analysis and issue identification, development of an action plan, and implementation and evaluation of the change process. The rapid-design process allowed bedside nurses to give ongoing feedback and see change occur based on that feedback.This kept the bedside nurses engaged in and supportive of this project.

This project provided insight into one unit’s unique needs. Opportunities for ongoing work identified by the nurses in this pilot unit included improving teamwork between nursing and ancillary personnel to accomplish breaks, increasing the nurses’ understanding of the effects of fatigue on their ability to provide safe care for patients, and sharing creative ways nurses were able to accomplish their breaks.

Enhancing meal and non-meal breaks may seem like a small change. Yet, utilizing the concept of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and NDNQI® data, nurses were able to see how important it was to address this basic human need. Their ability to utilize the toolkit to interpret their data and create a successful action plan to enhance meal and non-meal breaks has increased their confidence. With this success, there is an increased likelihood that these nurses will be better equipped to ‘move up’ Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and address identified higher level needs in the future. Ultimately, these successes will empower the bedside nurses, increase their satisfaction with their current work setting, and enable them to become the leaders in performance improvement activities rather than the followers.

Culture changes slowly; yet adequate data, appropriate tools, and strong leadership can facilitate this change. Hospitals need to be engaged in constant change. However, fluctuations in staffing and census, little downtime for staff, increased use of technology, computerized documentation, shortened length of stay, complexity, and reliance on multiple departments to accomplish work have created a chaotic practice environment. Anecdotal data, collective bargaining agreements, and case law suggest that nurses routinely sacrifice their breaks and meal periods to provide patient care in these very complex environments (Rogers, Hwang, & Scott, 2004). Such action on a routine basis, however, is neither prudent nor appropriate; it indicates a practice environment at odds with quality care. In this complex and chaotic environment, staff willingness to take meal and non-meal breaks will require a culture shift. Culture changes slowly; yet adequate data, appropriate tools, and strong leadership can facilitate this change. In this article we have provided an example of how this shift can occur with the help of a theoretical framework, such as Maslow’s, to frame for participants the change needed; NDNQI® data; and a belief in the ability of bedside nurses to bring about changes that will enhance their work environment and the safety of patient care.

Authors

Lisa Groff Paris, DNP, RNC-OB, C-EFM

E-mail: lgparis@gbmc.org

Dr. Groff Paris is an Education Specialist at the Greater Baltimore (MD) Medical Center. She received her BSN from University of Maryland, her Master’s Degree in Nursing Education from Hood College (Frederick, MD), and her DNP degree from Johns Hopkins School of Nursing (Baltimore). Lisa is certified in both Inpatient Obstetrical Nursing and Electronic Fetal Monitoring. She has worked for over 20 years developing and mentoring nurses in both academic and hospital-based, staff-development settings. She has focused her work on improving the practice environment of hospital bedside nurses, strengthening collaboration amongst healthcare professionals, and improving perinatal care outcomes.

Mary Terhaar, DSNc, RN

E-mail: mterhaa1@son.jhmi.edu

Dr. Terhaar is an Assistant Professor at Johns Hopkins School of Nursing (Baltimore). She received her BSN degree from Emmanuel College (Boston, MA), and both her MSN and DNSc degrees from The Catholic University of America in Washington DC. Dr. Terhaar has over 30 years of experience improving outcomes, supporting clinicians in practice, and developing the workforce and leadership for the future of nursing and healthcare. Her expertise and scholarship focus on enhancing interdisciplinary collaboration, developing strong professional practice environments, refining systems to support excellent outcomes, and developing expertise in the areas of perinatal and neonatal nursing.

© 2010 OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing

Article published December 7, 2010

References

AACN. Nursing shortage fact sheet. (2007). Retrieved March 19, 2010 from www.aacn.nche.edu/Media/FactSheets/NursingShortage.htm

Aiken, L.H., Clarke, S.P., & Sloane, D.M. (2002). Hospital staffing, organization and quality of care: cross national findings. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 14, 5-13.

Beaudoin, L.E., & Edgar, L. (2003). Hassles: Their importance to nurses’ quality of work life. Nurse Economy 21(3), 106-113.

Bowles, C., & Candela, L. (2005). First job experiences of recent RN graduates: Improving the work environment. Journal of Nursing Administration, 35(3), 130-137.

Chinnis, A.S., Summers, D.E., Doer, C., Paulson, D.J., & Davis, S.M. (2001). Q methodology: A new way of assessing employee satisfaction. Journal of Nursing Administration, 31(5), 252-259.

Cline, D., Reilly, C., & Moore, J.F. (2003). What’s behind RN turnover? Nursing Management, 34(10), 50-53.

DiMiglio, K., Padula, C., Piatek, C., Korber, S., Barrett, A., Ducharme, M.,…Corry, K. (2005). Group cohesion and nurse satisfaction: Examination of a team building approach. Journal of Nursing Administration, 35(3), 110-120.

Gallup. (2005). Nurse engagement key to reducing medical errors. Retrieved March 19, 2010 from: www.gallup.com/poll/20629/nurse-engagement-key-reducing-medical-errors.aspx

Heath, J., Johanson, W., & Blake, N. (2004). Healthy work environments: A validation of the literature. Journal of Nursing Administration, 34(11), 524-530.

Hoffman, E. (2008). The Maslow effect: A humanist legacy for nursing. American Nurse Today, 3(8), 36-37.

Holtom, B.C., & O’Neill, B.S. (2004). Job embeddedness: A theoretical foundation for developing a comprehensive nurse retention plan. Journal of Nursing Administration, 34(5), 216-227.

Hughes, R.G., & Rogers, A.E. (2004). Are you tired? Sleep deprivation compromises nurses’ health—and jeopardizes patients. American Journal of Nursing, 104(3), 36-38.

Institute of Medicine. (2004). Keeping patients safe: Transforming the work environment of nurses. Retrieved March 20, 2010 from http://books.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=10851&page=48

Kalisch, B.J., Curley, M., & Stefanov, S. (2007). An intervention to enhance nursing staff teamwork and engagement. Journal of Nursing Administration, 37(2), 77-84.

Kanter, R.M. (1993). Men and women of the corporation. 2nd Edition. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Kramer, M., & Schmalenber, C. (2008). Confirmation of a healthy work environment. Critical Care Nurse, 28, 56-63.

Kramer, M., Schmalenberg, C., Maguire, P., Brewer, B.B., Burke, R., Chmielewski, L., & Waldo, M. (2008). Structures and practices enabling staff nurses to control their practice. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 30(5), 539-559.

Lake, E.T. (2002). Development of the practice environment scale of the nursing work index. Research in Nursing & Health, 25, 176-188.

Laschinger, H.K.S., Almost, J., & Tuer-Hodes, D. (2003). Workplace empowerment and magnet hospital characteristics: Making the link. Journal of Nursing Administration, 33(7/8), 410-422.

Leurer, M.D., Donnelly, G., & Domm, E. (2007). Nurse retention strategies: Advice from experienced registered nurses. Journal of Health Organization and Management 21(3), 307-319.

Maslow, A.H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review 50, 70-396.

Montalvo, I. (2007). The national database of nursing quality indicatorsTM (NDNQI®). OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 12(3). DOI: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol12No03Man02

Rogers, A.E., Hwang, W.T., & Scott, L.D. (2004). The effects of work breaks on staff performance. Journal of Nursing Administration, 34(11), 512-519.

Rosenstein, A. (2002). Nurse-physician relationships: Impact on nurse satisfaction and retention. American Journal of Nursing, 102(6), 26-34.

Scott, L.D., Hofmeister, N., Rogness, N., & Rogers A.E. (2010). Implementing a fatigue countermeasures program for nurses: A focus group analysis. Journal of Nursing Administration, 40(5), 233-240.

Shader, K., Broome, M.E., Broome, C.D., West, M.E., & Nash, M. (2001) Factors influencing satisfaction and anticipated turnover for nurses in an academic medical center. Journal of Nursing Administration, 31(4), 210-216.

Stefancyk, A. (2009). One-Hour, Off-Unit Meal Breaks. American Journal of Nursing, 109(1), 64-66.

Zangaro, G.A. & Soeken, K.L. (2007). A meta-analysis of studies of nurses’ job satisfaction. Research in Nursing & Health 30, 445-458.