Moral distress occurs when one knows the ethically correct action to take but feels powerless to take that action. Research on moral distress among nurses has identified that the sources of moral distress are many and varied and that the experience of moral distress leads some nurses to leave their jobs, or the profession altogether. This article considers both moral distress and moral residue, a consequence of unresolved moral distress. First, we will explain the phenomenon of moral distress by providing an historical overview, identifying common sources, and describing strategies for recognizing moral distress. Next we will address moral residue and the crescendo effect associated with moral residue. We will conclude by considering ways to address moral distress and the benefits of a moral distress consult service.

Key words: moral distress, ethics, decision making, burnout, moral residue, moral integrity

Ethical debate in clinical settings can be productive and positive, a sign that healthcare providers are engaged in collaborative relationships and concerned about the quality of care for their patients. The presence of moral distress, however, signals a different issue altogether. Moral distress, in fact, is a sign that ethical challenges are not being addressed adequately. What is moral distress? Who is vulnerable? How is it recognized? What can be done about it? This article begins to answer these questions in order to provide a deeper understanding of this difficult, but persistent, problem in healthcare.

The Phenomenon of Moral Distress

In 1984, Andrew Jameton (1984) defined “moral distress” as a phenomenon in which one knows the right action to take, but is constrained from taking it. Moral distress is different from the classical ethical dilemma in which one recognizes that a problem exists, and that two or more ethically justifiable but mutually opposing actions can be taken. Often, in an ethical dilemma, there are significant downsides to each potential solution.

Consider the following case:

Mr. Anderson, a 92 year old man living in a nursing home and suffering with Alzheimer’s disease for over 10 years, reaches the stage where he is no longer able to swallow food effectively. He has been hospitalized with aspiration pneumonia four times in the last year. The man’s eldest child, who lives in the same town, has a durable power of attorney, and visits regularly, insists that a feeding tube be inserted. He has the support of his two siblings. The staff feels that a feeding tube would be distressing to the patient. Besides, they say, “He swats away our hands when we try to hold him down to insert the tube, and he always pulls the tube out.”

...moral distress occurs when an individual identifies the ethically appropriate action but that action cannot be taken. The dilemma here is that the family, legally authorized to make medical decisions for the patient, desires one action (inserting the feeding tube) and the staff, who manage the patient daily and who have the clinical knowledge of the ultimate outcome, desire an opposing action (not inserting the tube, rather providing comfort care). Thus there are two mutually exclusive courses of action both of which are ethically justifiable, and neither of which is optimal. If the family’s desires are followed, Mr. Anderson will endure having a feeding tube placed and his life will be prolonged. Yet one may ask how beneficial is a longer life for Mr. Anderson, and what are the social, familial, and financial costs of this action? On the other hand, if the staff’s desires are followed, Mr. Anderson will surely die sooner, and the family will likely feel abandoned and angry—an end-of-life situation all would desire to avoid. Again one must consider the social, familial, and financial costs of the action.

In contrast, moral distress occurs when an individual identifies the ethically appropriate action but but feels unable to take that action Consider this case:

Mr. Jones is an 82 year old nursing home resident who has multiple co-morbidities including significant dementia. He is combative and often kicks or punches those who attempt to care for him. In fact, three members of the staff (two nurses and a nursing assistant) have been treated in the emergency room for injuries that occurred during the course of caring for him. The man’s wife refuses medications to sedate him, saying that she is concerned about the side effects. Communicating the consistency and severity of the problem to the doctors, some of whom are there as consultants and all of whom only see Mr. Jones for brief intervals, is challenging. While the nursing staff are not willing to abandon Mr. Jones, they are afraid for their safety and are morally distressed because they feel forced to endure physical violence without any power to change the situation. They know that caring for Mr. Jones safely requires giving him medication, but they are constrained by the fact that the doctors, who must write the prescription, do not understand the extent of the problem and Mrs. Jones, the patient’s power of attorney, opposes any form of sedation. They feel trapped.

In this situation, there is not an ethical dilemma; the nurses are confident that the ethically appropriate action is to provide enough medication to Mr. Jones so as to permit safe care by the nursing staff, but not so much that he is obtunded and unable to respond to his environment. They are not torn between two opposing actions. However, they may feel powerless to take the right action and unable to communicate effectively with those who have the power to implement the ethically appropriate course of action. This is moral distress.

Historical Overview

In his early work defining moral distress, Jameton noted that the field of bioethics has placed greater emphasis on ethical dilemmas than on moral distress (Jameton, 1993). Because dilemmas involve weighing the ethical justification for alternative courses of action, they are ideal teaching tools, encouraging identification and discussion of ethical principles. In situations that engender moral distress, the ethically appropriate action is likely to have been identified. Thus, discussion of the ethical elements is less critical. Instead, addressing moral distress requires identification of social and organizational issues, and questions of accountability and responsibility.

Traditional ethics education that focuses on ethical dilemmas and underlying principles is inadequate to address situations involving moral distress. Moral distress was first recognized among nurses, and certainly the majority of studies have focused on this population. Although this article focuses on moral distress among nurses, it is important to note that moral distress is not solely a nursing problem. It has been identified among nearly all healthcare professionals, including physicians (Austin, Kagan, Rankel, & Bergum, 2008; Chen, 2009; Forde & Aasland, 2008; Hamric & Blackhall, 2007; Lee & Dupree, 2008; Lomis, Carpenter, & Miller, 2009), respiratory therapists (Schwenzer & Wang, 2006), pharmacists (Sporrong, Hoglund, Hansson, Westerholm, & Arnetz, 2005), psychologists (Austin, Rankel, Kagan, Bergum, & Lemermeyer, 2005), social workers (Chen, 2009), nutritionists (Chen, 2009), and chaplains (Chen, 2009). Between the professions, there appear to be differences in what causes moral distress and in how it is manifested (Austin, Rankel et al., 2005; Austin et al., 2008; Forde & Aasland, 2008; Hamric, Davis, & Childress, 2006; Hamric & Blackhall, 2007; Lee & Dupree, 2008; Lomis et al., 2009; Schwenzer & Wang, 2006; Sporrong et al., 2005). These differences are beyond the scope of this article, but it is critical that nurses understand that this is a multi-disciplinary problem.

Corley (2002) theorized that moral distress among nurses occurs when the nurse knows what is best for the patient but that course of action conflicts with what is best for the organization, other providers, other patients, the family, or society as a whole. Thus, moral distress occurs when the internal environment of nurses -- their values and perceived obligations -- are incompatible with the needs and prevailing views of the external work environment. Traditional ethics education that focuses on ethical dilemmas and underlying principles is inadequate to address situations involving moral distress. Values clarification, communication skills, and an understanding of the system in which healthcare is delivered are the tools necessary to address conflicts between the internal and external environments. Corley (2002) has noted that while moral distress can be devastating, leading nurses to consider leaving the profession, it can also have a positive impact by increasing nurses’ awareness of ethical problems.

Some broadening of the definition of moral distress has occurred in recent years. For example, Hanna’s (2004) analysis of small qualitative studies of moral distress revealed that although nurses do not consistently identify constraints on their behavior or conflicts with the work environment, they are consistent in describing symptoms of emotional distress and a sense of isolation because others do not grasp the moral elements they see. McCarthy and Deady (2008) cautioned researchers and authors to differentiate moral distress from emotional distress which is more generic and may occur in a stressful work environment but may not have an ethical element. In the case of Mr. Jones, nurses are certainly emotionally distressed, when they experience fear, frustration, and anger as they attempt to manage his care appropriately. However, there is more to this case than emotional distress. The nurses feel devalued and unheard. Thus, a moral element, not characteristic of emotional distress, is present. This moral element differentiates emotional distress from moral distress....moral distress involves a threat to one’s moral integrity.

Although implied but not explicitly stated in the earlier definition, moral distress involves a threat to one’s moral integrity. Moral integrity is the sense of wholeness and self-worth that comes from having clearly defined values that are congruent with one’s actions and perceptions (Hardingham, 2004). For the nurses caring for Mr. Jones, entering his room despite concerns for their own safety threatens not only their physical integrity, but their moral integrity as well.

Sources of Moral Distress

Situations that cause moral distress vary among individual providers just as values and obligations are individually interpreted. While nursing research has identified common sources of moral distress, not every nurse will experience distress when faced with these situations, and some nurses will experience distress from other circumstances. The following are commonly cited sources of moral distress among nurses, as noted by Corley (2002):

- Continued life support even though it is not in the best interest of the patient

- Inadequate communication about end of life care between providers and patients and families

- Inappropriate use of healthcare resources

- Inadequate staffing or staff who are not adequately trained to provide the required care

- Inadequate pain relief provided to patients

- False hope given to patients and families

As described by Jameton (1993) and also Corley, Elswick, Gorman, and Clor (2001), a key element in moral distress is the individual’s sense of powerlessness, the inability to carry out the action perceived as ethically appropriate. Jameton (1993) described this as occurring because of constraints on a nurse’s behavior. Constraints can be internal, such as fear of losing one’s job, self-doubt, anxiety about creating conflict, or lack of confidence (Hamric, Davis, & Childress, 2006). External constraints that contribute to moral distress include power imbalances between members of the healthcare team, poor communication between team members, pressure to reduce costs, fear of legal action, lack of administrative support, and hospital policies that conflict with patient care needs (Jameton, 1993). In the case above, the nurses providing care for Mr. Jones face an external constraint in that the documentation system did not effectively communicate the severity of Mr. Jones behavior to medical providers.

Recognizing Moral Distress

Moral distress often involves feelings of frustration and anger (Elpern, Covert, & Kleinpell, 2005; Wilkinson, 1988), which are fairly easy to recognize. Under the surface, and more difficult to identify, are the feelings that threaten one’s moral integrity—feeling belittled, unimportant, or unintelligent. Unfortunately, these feelings are often borne alone as professionals are often hesitant to speak openly about their impotence. As a result, morally distressed individuals may also feel isolated, an additional threat to their integrity.

...in any given situation, not everyone will be morally distressed. One complicating factor which adds to the feeling of isolation is that in any given situation, not everyone will be morally distressed. Because values and obligations are perceived differently by various members of the healthcare team, moral distress is an experience of the individual rather than an experience of the situation. In the case of Mr. Jones, for instance, there are likely to be nurses who are quite morally distressed. There are equally likely to be nurses who are not morally distressed. The nurses who do not feel moral distress are not morally insensitive or deficient persons. In other situations, they may experience significant moral distress.

Thus far, we have described how moral distress is defined, when it is likely to occur, and how to recognize it. Many argue that moral distress in healthcare ‘comes with the territory.’ While some moral distress may be inevitable, it must be attended to or the effects will be damaging. In fact, there is increasing evidence that repeated exposure to moral distress can devastate one’s moral sensitivity to problematic clinical situations, as well as to one’s career. The damage occurs as levels of moral residue increase as described below.

Moral Residue

Jameton noted that moral distress tended to linger, and called this lingering moral distress “reactive distress” (1993). Today, this lingering distress is recognized as a concept that is different from, yet related to, moral distress. It is called “moral residue.” This phenomenon has been described best by Webster and Bayliss who said that moral residue is “that which each of us carries with us from those times in our lives when in the face of moral distress we have seriously compromised ourselves or allowed ourselves to be compromised” (2000, p. 208). In situations of moral distress, one’s moral values have been violated due to constraints beyond one’s control. After these morally distressing situations, the moral wound of having had to act against one’s values remains. Moral residue is long-lasting and powerfully integrated into one’s thoughts and views of the self. It is this aspect of moral distress—the residue that remains—that can be damaging to the self and one’s career, particularly when morally distressing episodes repeat over time.

The Crescendo Effect: Cause for Concern

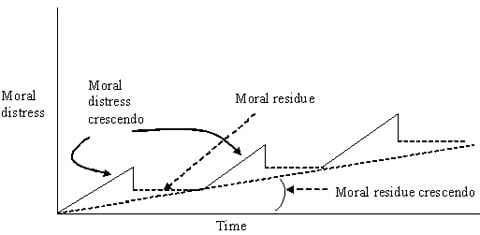

Moral distress and moral residue are closely related concepts, but each has unique aspects. A preliminary model for the interaction between these concepts, the crescendo effect, has been described by Epstein and Hamric (2009) (See Figure). The model includes a dual crescendo effect, one of moral distress and one of moral residue.

Figure. Crescendo Effect (solid lines indicate moral distress, dotted lines indicate moral residue). Permission has been granted by the Journal of Clinical Ethics to use this Figure.

|

Each time a morally distressing situation occurs and resolves, the level of residual moral distress rises. The moral distress crescendo occurs as a clinical situation unfolds. In the case of Mr. Jones, nurses caring for him may have noticed moral distress within a few days of his admission to the nursing home. These nurses know that the right action is to medicate him, if only briefly, so that he is unable to hurt the staff or himself, particularly in his fragile neurologic and physical state. As time passes, the nurses sense that no one seems to believe the magnitude of the difficulty. They feel that they are forced to put themselves and the patient at risk for physical injury. They are not being heard, and their level of moral distress rises. The administration does nothing to help despite repeated pleas. The physicians play down the problem, saying, “He doesn’t bother us when we examine him.” Suppose that Mr. Jones suffers a stroke and is admitted to a local hospital for further evaluation. Although some nurses may have continued distress because they know that the hospital nurses are about to encounter what they have been dealing with for the past several weeks, the level of moral distress drops precipitously because the situation, in effect, is resolved. However, the level of moral distress does not drop to zero. Rather, there is a residual level of moral distress. These nurses reflect on the lack of importance this problem received and on their feelings of having been powerless and voiceless, despite their expertise and experiences with the patient. This is moral residue, the continuing understanding that one’s moral concerns have not been acknowledged, and that, as a result, right action was not taken.

The moral residue crescendo occurs after repeated situations of moral distress. Each time a morally distressing situation occurs and resolves, the level of residual moral distress rises. Thus, moral residue rises gradually. Exacerbating moral residue is the fact that morally distressing problems in a given clinical setting tend to be similar over time. Additionally, new situations remind providers of their powerlessness in past situations, and the crescendo builds. For example, in the intensive care setting, prolonged aggressive treatment with little hope of survival is a common, repeated source of moral distress (Corley, 1995; Epstein, 2008; Hamric & Blackhall, 2007). The moral distress that is generated has less to do with the individual patient than with the dreaded feeling of “here we go again.” Thus, the sheer repetitive nature of similar clinical situations evoking moral distress adds a sense of futility, increasing the moral residue.

The concern is that as the moral residue crescendo rises over time due to repeated episodes of moral distress, a breaking point may occur. As noted by Epstein and Hamric (Epstein & Hamric, 2009), there are three potential consequences of moral distress and moral residue. The first consequence is that providers may become morally numbed to ethically challenging situations. They may no longer recognize or engage in clinical situations requiring moral sensitivity. Second, providers may engage in different ways of conscientiously objecting to the trajectory of the situation (Catlin et al., 2008). Conscientious objection more forcefully makes an opinion known to overcome constraints. Some methods of objection may be more productive (i.e., calling an ethics consult) than others (i.e., documenting dissent in a patient’s chart). The final and perhaps most damaging consequence is burnout. Recent research shows a correlation between moral distress and aspects of burnout (Meltzer & Huckabay, 2004). In fact, several studies have shown that nurses have considered leaving their position or even their profession due to moral distress (Corley, 1995; Hamric & Blackhall, 2007). The concern is that as the moral residue crescendo rises over time due to repeated episodes of moral distress, a breaking point may occur. The findings of two studies have suggested that years of experience is correlated with level of moral distress (Elpern et al., 2005; Hamric & Blackhall, unpublished data), although this finding is inconsistent (Corley et al., 2001). In the current era of nursing shortage, the healthcare system can ill-afford to lose valuable and morally invested clinicians.

Addressing Moral Distress

Nursing alone cannot change the work environment. Multiple views and collaboration are needed to improve a system. Recently, several approaches to reducing moral distress (and moral residue) have been published. Although further research is necessary to determine the degree of effectiveness of these approaches, their foundations are solid and they are, at least in part, useful to nurses at the bedside. The nurses can tailor the strategies described below to an individual, unit, or organizational setting as appropriate.

American Association of Critical Care Nurses 4 A’s

The American Association of Critical Care Nurses (AACN, 2005) has targeted moral distress as a priority area and has developed the 4 A’s approach to address and reduce moral distress (AACN, n.d.; Rushton, 2006). Although designed initially for the critical care setting, the 4 A’s are adaptable and applicable in many non-critical care settings. The 4 A’s are: ASK, AFFIRM, ASSESS, and ACT. They are summarized below. Readers are encouraged to see AACN (n.d.) for a rich, full description of the 4 A’s.

ASK: Review the definition and symptoms of moral distress and ask yourself whether what you are feeling is moral distress. Are your colleagues exhibiting signs of moral distress as well?

AFFIRM: Affirm your feelings about the issue. What aspect of your moral integrity is being threatened? What role could you (and should you) play?

ASSESS: Begin to put some facts together. What is the source of your moral distress? What do you think is the “right” action and why is it so? What is being done currently and why? Who are the players in this situation? Are you ready to act?

ACT: Create a plan for action and implement it. Think about potential pitfalls and strategies to get around these pitfalls.

Other Strategies

Several authors have discussed other strategies for addressing moral distress (Austin, Lemermeyer, Goldberg, Bergum, & Johnson, 2005; Beumer, 2008; Epstein & Hamric, 2009; Hamric, Davis, & Childress, 2006; Lilly et al., 2000; Puntillo & McAdam, 2006). Their suggestions are compiled in the Table. While this is not an exhaustive list, these strategies can be adapted to any workplace setting. It is not necessary to complete every strategy; rather, try those that might work best in a specific work setting. See Box 1 and Box 2 for examples of moral distress and the use of suggested strategies.

|

Table. Strategies to reduce moral distress |

|

|

Strategy |

Implementation |

|

Speak up! |

Identify the problem, gather the facts, and voice your opinion |

|

Be deliberate |

Know who you need to speak with and know what you need to speak about |

|

Be accountable |

Sometimes, our actions are not quite right. Be ready to accept the consequences, should things not turn out the way you had planned. |

|

Build support networks |

Find colleagues who support you or who support acting to address moral distress. Speak with one authoritative voice. |

|

Focus on changes in the work environment |

Focusing on the work environment will be more productive than focusing on an individual patient. Remember, similar problems tend to occur over and over. It’s not usually the patient, but the system, that needs changing. |

|

Participate in moral distress education |

Attend forums and discussions about moral distress. Learn all you can about it. |

|

Make it interdisciplinary |

Many causes of moral distress are interdisciplinary. Nursing alone cannot change the work environment. Multiple views and collaboration are needed to improve a system, especially a complex one, such as a hospital unit. |

|

Find root causes |

What are the common causes of moral distress in your unit? Target those. |

|

Develop policies |

Develop policies to encourage open discussion, interdisciplinary collaboration, and the initiation of ethics consultations. |

|

Design a workshop |

Train nursing staff to recognize moral distress, identify barriers to change, and create a plan for action. |

|

In the medical intensive care unit of an academic medical center, a 67 year old woman with sepsis and multi-organ failure begins having runs of ventricular tachycardia in the early morning hours. Her nurse, Janet, calls the resident to the bedside. In discussing the situation, Janet suggests that the patient’s family be called in, stating her belief that the patient is not likely to survive much longer. The resident orders an EKG and other diagnostic testing to determine the cause of the arrhythmia, and then calls the family. He reports back to the nurse that the family is on their way, and as they further discuss the patient’s situation, she goes into sustained ventricular tachycardia deteriorating to ventricular fibrillation The two begin CPR and soon a crowd of interns and residents arrives in response. The family arrives on the unit and another nurse quickly directs them to the waiting room and then informs the resident of their arrival. The resident continues to run the code, telling the interns to switch off in doing compressions “so everyone gets a chance to learn.” The nurse reminds him that the family has arrived and that the patient’s situation and desire for CPR should be discussed with them. The resident replies that he plans to talk with them but first wants the interns to get some practice with a real code situation. The nurse is deeply distressed by this treatment of the patient but feels alone in the room full of doctors.

While Janet initially feels powerless in this situation, she also recognizes that she must take action. She knows that the hospital’s mission includes the education and training of residents and interns, and recognizes that this is in conflict with the professional value she places on her patient’s autonomy. She considers using physical force to stop the CPR until the resident addresses the patient’s family. She also considers refusing to participate in the code and walking out of the room. Additionally, she could consult with the attending physician, another nurse, and/or the nurse manager; however, she feels that there is not time for this. The action she selects is to speak firmly and calmly to the resident with whom she has collaborated in the past in the care of critically ill patients. She tells the resident that if he is not able to go talk to the family, she will have another nurse cover for her so she can talk to the family herself and determine if the resuscitation is an intervention the patient would desire. |

|

Elizabeth is a nurse in an orthopedic unit where the ratio of nurses to patients is one to six. A year ago, the hospital implemented a policy that patients being discharged from surgical services should leave by noon. To encourage adherence to this policy, the discharge coordinators who succeed in discharging at least 75% of their patients by noon are recognized on a bulletin board posted in the hospital cafeteria. Elizabeth has already been involved in several situations in which she questioned the safety of expedited discharge. In one situation, her patient was discharged before she had a chance to review his medication list with him. In another, the patient was discharged with instructions to change his surgical dressing but without anyone assessing his proficiency with this procedure. Today, Elizabeth is caring for a 76-year-old woman with a hip fracture who will be discharged to her daughter’s home. In discussing the patient’s care with her daughter, Elizabeth learns that the daughter works full time and that the patient will be alone in the home for most of the day. She calls the discharge coordinator to explain the need for a social work consult but is told, “We decided all this yesterday. She is going home today, and by 12 noon, no later.” Elizabeth recognizes the sense of powerlessness she felt in the past situations in which she did not dispute the discharge. She thinks, “Here I go again, I’m going to leave today feeling awful.” As she continues to participate in discharging patients without adequate teaching or planning, Elizabeth is developing moral residue. Each time a similar situation occurs, her degree of distress is heightened because the past distress was never resolved. Realizing that she cannot continue to function effectively as a staff nurse on this unit if these situations continue to reoccur, Elizabeth decides to seek help. She consults the nurse manager and the unit’s clinical nurse specialist to explain her concern. They are supportive of Elizabeth’s concerns and the CNS agrees to assist in having the patient’s discharge delayed. |

Moral Distress Consult Service

Moral residue...is the sum of the nicks in one’s moral integrity and the self-punishment inflicted when one does not do the right thing. Our institution has implemented a hospital-wide Moral Distress Consult Service (MDCS) to address issues of moral distress as they arise, similar to a more traditional Ethics Consult Service. Consultants from the MDCS meet with unit personnel, discuss the issue at hand, and help the staff strategize (using those strategies listed in the Table) to decrease the current moral distress, to bring attention to the fact that morally distressing situations tend to recur, and to begin to think about how to reduce or prevent future situations. This service provides a summary of each consultation. The summary is given to the group who requested the consult. The group can use the summary to help design and implement interventions to reduce moral distress on the unit. Follow-up and further consultation are provided as necessary.

Conclusion

Moral distress and moral residue are issues of concern for different reasons. Moral distress occurs in the day-to-day setting and involves situations in which one acts against one’s better judgment due to internal or external constraints. Putting aside one's values and carrying out an action one believes is wrong threatens the authenticity of the moral self. Unfortunately, situations of moral distress are common in healthcare, and damage to providers’ moral integrity occurs with alarming frequency. Some moral distress is likely inevitable. However, the strategies summarized above, as well as other strategies, can reduce the level of moral distress, or circumvent commonly occurring situations of moral distress, to maintain the moral integrity of staff and the unit as a whole, and prevent progression of the moral residue crescendo.

...situations of moral distress are common in healthcare....The goal is to preserve moral sensitivity and integrity by being recognized, valued, and heard. Moral residue is not a day-to-day issue. Instead, it grows quietly after each exposure to moral distress. It is the sum of the nicks in one’s moral integrity and the self-punishment inflicted when one does not do the right thing. Moral residue can lead to withdrawal, conscientious objection, or burnout, none of which is optimal or even acceptable for highly skilled, highly caring healthcare providers.

Intervening to address moral distress achieves several goals. First, it gives a name to a phenomenon that has, until recently, been an unrecognized hazard in the healthcare arena. Second, it reduces the threat to providers’ moral integrity. Even if moral distress cannot be completely removed, at least the angle of the moral distress crescendo can be flattened so that the level of moral distress does not climb so high. Third, it provides an avenue for those who are without power in certain circumstances to voice their opinion and to be heard. This does not necessarily mean that this voice will be the final voice or that the opinion will be followed. That is not the goal. The goal is to preserve moral sensitivity and integrity by being recognized, valued, and heard. Fourth, it allows moral distress to be recognized as a multi-disciplinary problem. Moral distress is not a nursing problem. Other providers are known to experience moral distress as well. Regardless of where a provider is in the healthcare hierarchy, there is always someone above and there is always someone below. As a result, there is always potential for powerlessness, for being trapped, and for being morally upended. This must be acknowledged if we are to move forward as ethically grounded, healthcare professionals. Finally, addressing moral distress reduces the crescendo of moral residue. Addressing moral distress and working to reduce the crescendo may slow the exodus of healthcare professionals from their professions, preserve moral sensitivity and integrity among skilled staff, and increase awareness of powerlessness in healthcare settings, ultimately benefitting providers and patients alike.

Authors

Elizabeth G. Epstein, PhD, RN

E-mail: meg4u@virginia.edu

Dr. Epstein is an Assistant Professor of Nursing and Faculty Affiliate for the Center for Biomedical Ethics and Humanities at the University of Virginia (Charlottesville). She conducts research in end-of-life issues and ethics in the Newborn Intensive Care (NICU) setting, and teaches ethics in the School of Nursing. She is currently serving as co-chair of the Moral Distress Consult Service at the University of Virginia, and is chair-elect of the Affinity Group for Nursing of the American Society for Bioethics. Dr. Epstein received her BS in biochemistry from the University of Rochester (New York), and her MS in pharmacology, along with her BSN and PhD in nursing, from the University of Virginia.

Sarah Delgado, MSN, RN ACNP-BC

E-mail: sad4n@virginia.edu

Sarah Delgado is an Assistant Professor of Nursing at the University of Virginia (Charlottesville), School of Nursing and a nurse practitioner at the University of Virginia Health System. She teaches clinical courses in the acute care graduate program and ethics in the undergraduate program. She also serves as a facilitator on the Moral Distress Consult Service. Her clinical focus is on the management of patients with HIV and AIDS, and her research focuses on the application of cellular technology to address health disparities in rural patients. She received both her BSN and her MSN from the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia).

References

AACN. (n.d.).4 as to rise above moral distress. Retrieved from www.aacn.org/WD/Practice/Docs/4As_to_Rise_Above_Moral_Distress.pdf

AACN. (2005). AACN standards for establishing and sustaining healthy work environments. Retrieved from www.aacn.org/WD/HWE/Content/hwehome.pcms?menu=Community

Austin, W., Lemermeyer, G., Goldberg, L., Bergum, V., & Johnson, M. S. (2005). Moral distress in healthcare practice: The situation of nurses. HEC Forum, 17(1), 33-48.

Austin, W., Rankel, M., Kagan, L., Bergum, V., & Lemermeyer, G. (2005). To stay or to go, to speak or stay silent, to act or not to act: Moral distress as experienced by psychologists. Ethics & Behavior, 15(3), 197-212.

Austin, W. J., Kagan, L., Rankel, M., & Bergum, V. (2008). The balancing act: Psychiatrists' experience of moral distress. Medicine, Health Care & Philosophy, 11(1), 89-97.

Beauchamp, T. & Childress, J. (2009). Principles of biomedical ethics. 6th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Beumer, C. M. (2008). Innovative solutions: The effect of a workshop on reducing the experience of moral distress in an intensive care unit setting. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing, 27(6), 263-267.

Catlin, A., Armigo, C., Volat, D., Vale, E., Hadley, M. A., Gong, W.,…Anderson, K. (2008). Conscientious objection: A potential neonatal nursing response to care orders that cause suffering at the end of life? Study of a concept. Neonatal Network, 27(2), 101-108.

Chen, P. (2009, February 5). When nurses and doctors can't do the right thing. Retrieved June 30, 2010 from www.nytimes.com/2009/02/06/health/05chen.html.

Corley, M. C. (1995). Moral distress of critical care nurses. American Journal of Critical Care, 4(4), 280-285.

Corley, M. C. (2002). Nurse moral distress: A proposed theory and research agenda. Nursing Ethics, 9(6), 636-650.

Corley, M. C., Elswick, R. K., Gorman, M., & Clor, T. (2001). Development and evaluation of a moral distress scale. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 33(2), 250-256.

Elpern, E. H., Covert, B., & Kleinpell, R. (2005). Moral distress of staff nurses in a medical intensive care unit. American Journal of Critical Care, 14(6), 523-530.

Epstein, E. G. (2008). End-of-life experiences of nurses and physicians in the newborn intensive care unit. Journal of Perinatology, 28, 771-778.

Epstein, E. G., & Hamric, A. B. (2009). Moral distress, moral residue, and the crescendo effect. Journal of Clinical Ethics, 20(4), 330-342.

Forde, R., & Aasland, O.G. (2008). Moral distress among Norwegian doctors. Journal of Medical Ethics, 34(7), 521-525.

Hamric, A. B., & Blackhall, L. J. (2007). Nurse-physician perspectives on the care of dying patients in intensive care units: Collaboration, moral distress, and ethical climate. Critical Care Medicine, 35(2), 422-429.

Hamric, A. B., Davis, W. S., & Childress, M. D. (2006). Moral distress in health care professionals. Pharos, 69(1), 16-23.

Hanna, D. R. (2004). Moral distress: The state of the science. Research & Theory for Nursing Practice, 18(1), 73-93.

Hardingham, L. B. (2004). Integrity and moral residue: Nurses as participants in a moral community. Nursing Philosophy, 5(2), 127-134.

Jameton, A. (1984). Nursing practice: The ethical issues. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Jameton, A. (1993). Dilemmas of moral distress: Moral responsibility and nursing practice. AWHONNS Clinical Issues in Perinatal & Womens Health Nursing, 4(4), 542-551.

Lee, K. J., & Dupree, C. Y. (2008). Staff experiences with end-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 11(7), 986-990.

Lilly, C. M., De Meo, D. L., Sonna, L. A., Haley, K. J., Massaro, A. F., Wallace, R. F., & Cody, S. (2000). An intensive communication intervention for the critically ill. American Journal of Medicine, 109(6), 469-475.

Lomis, K. D., Carpenter, R. O., & Miller, B. M. (2009). Moral distress in the third year of medical school; a descriptive review of student case reflections. American Journal of Surgery, 197(1), 107-112.

McCarthy, J., & Deady, R. (2008). Moral distress reconsidered. Nursing Ethics, 15(2), 254-262.

Meltzer, L. S., & Huckabay, L. M. (2004). Critical care nurses' perceptions of futile care and its effect on burnout. American Journal of Critical Care, 13(3), 202-208.

Puntillo, K. A., & McAdam, J. L. (2006). Communication between physicians and nurses as a target for improving end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: Challenges and opportunities for moving forward. Critical Care Medicine, 34(11 Suppl), S332-40.

Rushton, C. H. (2006). Defining and addressing moral distress: Tools for critical care nursing leaders. AACN Advanced Critical Care, 17(2), 161-168.

Schwenzer, K. J., & Wang, L. (2006). Assessing moral distress in respiratory care practitioners. Critical Care Medicine, 34(12), 2967-2973.

Sporrong, S. K., Hoglund, A. T., Hansson, M. G., Westerholm, P., & Arnetz, B. (2005). "We are white coats whirling round"--moral distress in Swedish pharmacies. Pharmacy World & Science, 27(3), 223-229.

Webster, G., & Bayliss, F. (2000). Moral residue. In S. Rubin, & L. Zoloth (Eds.), Margin of error: The ethics of mistakes in the practice of medicine. Hagerstown, MD: University Publishing Group, Inc.

Wilkinson, J. M. (1988). Moral distress in nursing practice: Experience and effect. Nursing Forum, 23(1), 16-29.