The National Database of Nursing Quality IndicatorsTM (NDNQI®) is the only national nursing database that provides quarterly and annual reporting of structure, process, and outcome indicators to evaluate nursing care at the unit level. Linkages between nurse staffing levels and patient outcomes have already been demonstrated through the use of this database. Currently over 1100 facilities in the United States contribute to this growing database which can now be used to show the economic implications of various levels of nurse staffing. The purpose of this article is to describe the work and accomplishments related to the NDNQI as researchers utilize its nursing-sensitive outcomes measures to demonstrate the value of nurses in promoting quality patient care. After reviewing the history of evaluating nursing care quality, this article will explain the purpose of the NDNQI and describe how the database has been operationalized. Accomplishments and future plans of the NDNQI will also be discussed.

Key Words: nursing-sensitive indicators, quality, nurse staffing, patient outcomes, nursing outcomes, performance measurement

Quality is a broad term that encompasses various aspects of nursing care. Various health care measures have been identified over the years as indicators of health care quality (American Nurses Association, 1995; Institute of Medicine, 1999, 2001, 2005; Joint Commission, 2007). In 2004, the National Quality Forum (NQF), via its voluntary consensus standards process, endorsed 15 national standards to be used in evaluating nursing-sensitive care. These standards are now known as the NQF 15 (Kurtzman & Corrigan, 2007). The purpose of this article is to describe the work and accomplishments related to the National Database of Nursing Quality IndicatorsTM (NDNQI®) as researchers utilize its nursing-sensitive outcomes measures to demonstrate the value of nurses in promoting quality patient care. After reviewing the history of evaluating nursing care quality, this article will explain the purpose of the NDNQI and describe how the database has been operationalized. Accomplishments and future plans of the NDNQI will also be discussed.

History of Evaluating Nursing Care Quality

Evaluating the quality of nursing practice began when Florence Nightingale identified nursing's role in health care quality and began to measure patient outcomes. She used statistical methods to generate reports correlating patient outcomes to environmental conditions (Dossey, 2005; Nightingale, 1859/1946). Over the years, quality measurement in health care has evolved. The work done in the 1970s by the American Nurses Association (ANA), the wide dissemination of the Quality Assurance (QA) model (Rantz, 1995), and the introduction of Donabedian's structure, process, and outcomes model (Donabedian, 1988, 1992) have offered a comprehensive method for evaluating health care quality.

The workforce restructuring and redesign prevalent in the early 1990s demonstrated the need for the ANA to evaluate nurse staffing and identify linkages between nurse staffing and patient outcomes.The workforce restructuring and redesign prevalent in the early 1990s demonstrated the need for the ANA to evaluate nurse staffing and identify linkages between nurse staffing and patient outcomes. In 1994 the ANA Board of Directors asked ANA staff to investigate the impact of these changes on the safety and quality of patient care. In 1994, ANA launched the Patient Safety and Quality Initiative (ANA, 1995). A series of pilot studies across the United States were funded by ANA to evaluate linkages between nurse staffing and quality of care (ANA, 1996a, 1997, 2000a, 2000b, 2000c). Multiple quality indicators were identified initially. Evidence of the effectiveness of these indicators was used to adopt a final set of 10 nursing-sensitive indicators to use in evaluating patient care quality (Gallagher & Rowell, 2003). Implementation guidelines were subsequently published (ANA, 1996b, 1999).

Nursing-sensitive indicators identify structures of care and care processes, both of which in turn influence care outcomes. Nursing-sensitive indicators are distinct and specific to nursing, and differ from medical indicators of care quality. For example, one structural nursing indicator is nursing care hours provided per patient day. Nursing outcome indicators are those outcomes most influenced by nursing care.

Purpose of the NDNQI®

In 1998, the National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators was established by ANA so that ANA could continue to collect and build on data obtained from earlier studies and further develop nursing's body of knowledge related to factors which influence the quality of nursing care. Linkages between nurse staffing and patient outcomes had already been identified, but continued data collection and reporting was necessary to evaluate nursing care quality at the unit level and thus fulfill nursing's commitment to evaluating and improving patient care.

Nursing's foundational principles and guidelines identify that as a profession, nursing has a responsibility to measure, evaluate, and improve practice. This is stated in two of nursing's guiding documents:

The Code of Ethics for Nurses with Interpretative Statements states: The nurse promotes, advocates for, and strives to protect the health, safety, and rights of the patient (ANA, 2001, p.12).

Nursing: Scope & Standards of Practice, Standard 7 states: The registered nurse systematically enhances the quality and effectiveness of nursing practice (ANA, 2004. p. 33).

The Utilization Guide for the ANA Principles for Nurse Staffing recognizes that in order to measure sufficiency of staffing on an ongoing basis, at a minimum, unit level nursing-sensitive structure, process, and outcome indicators need to be collected (ANA, 2005). NDNQI's mission is to aid the nurse in patient safety and quality improvement efforts... NDNQI's mission is to aid the nurse in patient safety and quality improvement efforts by providing research-based, national, comparative data on nursing care and the relationship of this care to patient outcomes.

Operationalization of the National Database

The NDNQI® database is managed at the University of Kansas Medical Center (KUMC) School of Nursing under contract to ANA with fiscal and legal support provided by KUMC Research Institute (KUMCRI). A health care facility that is interested in joining the NDNQI submits a signed contract and fee, based on hospital size, to KUMCRI, along with information on the person who will be the facility's NDNQI® primary point of contact. This person is then identified as the NDNQI Site Coordinator. The NDNQI Site Coordinator serves as the interface between the participating facility and the NDNQI liaisons working at the University of Kansas. The NDNQI® liaisons provide ongoing assistance and support to health care facilities at multiple levels. For example they provide help in identifying nursing units appropriately for data entry; offer web-based, data-entry tutorials; conduct pilot testing; and answer questions about definitions and the reading of reports. NDNQI® researchers are also available to answer questions related to the database or the nursing measures.

Education on NDNQI and nursing-sensitive indicators has been ongoing for participating facilities since 1999. Facilities have quarterly conference calls with NDNQI® staff to review any changes or updates to the indicators or database. They also have the opportunity to participate in pilot studies performed when an indicator is being evaluated for implementation.

Once access to the database has been provided, the facility NDNQI® Site Coordinator will work with NDNQI staff from the University of Kansas to correctly classify the nursing units. This is an important step to ensure nursing units are classified appropriately prior to data entry. The facility NDNQI Site Coordinator and other authorized hospital staff also complete web-based tutorials to learn about each indicator prior to initial data submission.The facility NDNQI Site Coordinator has continuous access to the indicator definitions and is responsible for aligning the hospital data collected to NDNQI definitions. The facility NDNQI Site Coordinator has continuous access to the indicator definitions and is responsible for aligning the hospital data collected to NDNQI definitions. On average, it takes three months to join the database and start data submission. The NDNQI is then dependent on hospitals correctly submitting the data on a quarterly basis. All data is submitted electronically via the intranet in a secure website or by XML submission. Data checks and error reports are conducted on an ongoing basis by participating facilities and by NDNQI staff to ensure data integrity.

As of the writing of this article, the NDNQI has implemented six of the ten original ANA-endorsed NDNQI indicators (See Table 1). The initial set of indicators used in establishing the database was selected based on feasibility testing. These indicators included: Falls, Falls with Injury, Nursing Care Hours per Patient Day, Skill Mix, Pressure Ulcer Prevalence, and Hospital-Acquired Pressure Ulcer Prevalence. The RN job satisfaction indicator was pilot tested in 2001 and subsequently implemented in 2002. The RN satisfaction survey is an important indicator to assist nursing leaders and staff in evaluating the work environment so as to facilitate nursing retention and recruiting efforts.

| Table 1. NDNQI Indicators | ||

|

Indicator |

Sub-indicator |

Measure(s) |

|

a. Registered Nurses (RN) b. Licensed Practical/Vocational Nurses (LPN/LVN) c. Unlicensed Assistive Personnel (UAP) |

Structure |

|

|

2. Patient Falls1,2 |

Process & Outcome |

|

|

3. Patient Falls with Injury1,2 |

a. Injury Level |

Process & Outcome |

|

4. Pediatric Pain Assessment, Intervention, Reassessment (AIR) Cycle |

Process |

|

|

5. Pediatric Peripheral Intravenous Infiltration Rate |

Outcome |

|

|

6. Pressure Ulcer Prevalence1 |

a. Community Acquired b. Hospital Acquired c. Unit Acquired |

Process & Outcome |

|

7. Psychiatric Physical/Sexual Assault Rate |

Outcome |

|

|

8. Restraint Prevalence2 |

Outcome |

|

|

9. RN Education /Certification |

Structure |

|

|

10. RN Satisfaction Survey Options1,3 |

a. Job Satisfaction Scales b. Job Satisfaction Scales – Short Form c. Practice Environment Scale (PES)2 |

Process & Outcome |

|

11. Skill Mix: Percent of total nursing hours supplied by1,2 |

a. RN’s b. LPN/LVN’s c. UAP d. % of total nursing hours supplied by Agency Staff |

Structure |

|

12. Voluntary Nurse Turnover2 |

Structure |

|

|

13. Nurse Vacancy Rate |

Structure |

|

|

14. Nosocomial Infections(Pending for 2007) a. Urinary catheter-associated urinary tract infection (UTI)2 b. Central line catheter associated blood stream infection (CABSI)1,2 c. Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP)2 |

Outcome |

|

Pediatric and psychiatric indicators have been added more recently because participating hospitals requested indicators for these areas. Additional NQF endorsed measures (Table 1) were then added to the database because these represented additional nursing measures available that had already gone through a consensus measure approval process. ANA supported the addition of these measures to the database because they were of interest nationally to the nursing profession and were in concert with ANA's seminal work and ongoing support of nursing measures.

Implementing an indicator is a multi-step process (Table 2) that includes evaluating the evidence that a specified indicator is nurse sensitive and then pilot testing (Table 3) of the indicator by participating facilities. In addition, ...there is ongoing monitoring and testing for validity and reliability per NDNQI standard operating procedure. there is ongoing monitoring and testing for validity and reliability per NDNQI standard operating procedure. An outcome indicator is deemed to be nursing sensitive if there is a correlation or multivariate association between some aspect of the nursing workforce or a nursing process and the outcome. The NDNQI utilizes state-of-the-science methods, such as the hierarchical mixed model, to assess the strength of correlation between nursing workforce characteristics and outcomes (Gajewski et al., 2007; Hart, et al., 2006).

| Table 2. Indicator Development Process |

|

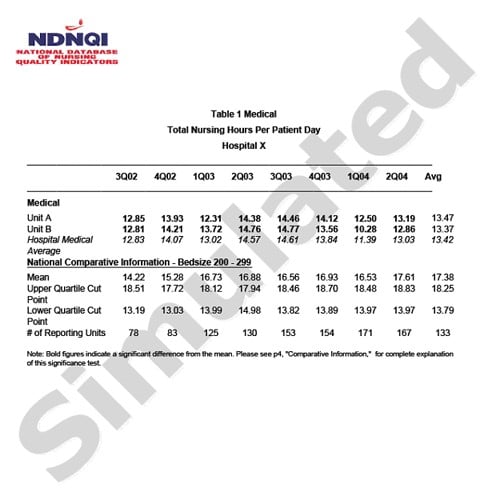

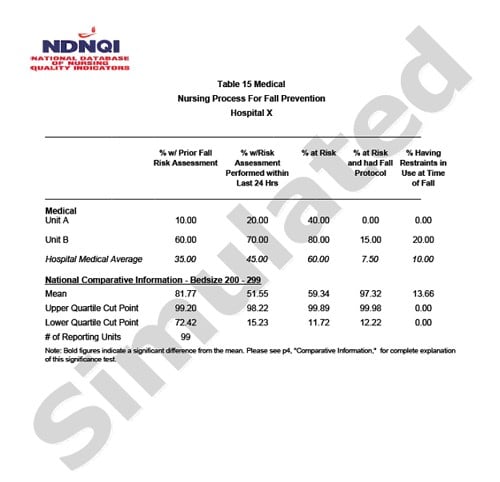

Quarterly Reports are downloaded electronically from the web by participating facilities. Reports can be downloaded in Adobe PDF, or Microsoft Excel format to facilitate data sharing and dissemination within a given institution. Figure 1 provides a sample of two tables from the report. The reports range from 25-200+ pages based on the number of nursing units and indicators for which hospitals submit data. The reports provide the most current eight quarters worth of data and a rolling average of those eight quarters with national comparisons at the unit level based on patient type, unit type, hospital bed size, and statistical significance of unit performance. For example, patient falls with injury could be reported for each adult medical unit of a 100-199 bed facility. The means for all medical units in a given-size facility can be compared with national standards for a given, nursing-sensitive indicator. The process measures associated with falls are collected and reported as well as the outcome measure of a patient fall.

|

|

|

|

The significance of offering the reports at the unit level is that such reports provide data regarding the specific site where the care occurs and provides a better comparison among like units. The significance of offering the reports at the unit level is that such reports provide data regarding the specific site where the care occurs and provides a better comparison among like units. Nursing leaders at participating facilities have used the information to advocate for more staff or a different mix of staff based on their comparisons of units in comparable facilities nation wide. Staff are also able to identify whether their performance improved after they intervened in an area needing improvement, e.g., a decrease in the fall rate due to implementation of a new protocol.

Some facilities join NDNQI as part of their MagnetTM Journey to report nursing-sensitive indicators. The Magnet facilities represent about 20% of the database. The remaining 80% of NDNQI-participating facilities join because they believe in the value of evaluating the quality of nursing care and improving outcomes, activities which are both basic responsibilities of the profession. NDNQI is also used to aid in the recruitment and retention of nurses by hospitals that use the annual RN Survey data and quarterly data to improve work environments, to staff based on patient outcomes, and to meet regulatory or state reporting requirements.

Broad Accomplishments

NDNQI accomplishments include development of nationally accepted measures to assess the quality of nursing care, improvements in training procedures for data submission, identification of nursing workforce structures and processes that influence outcomes, and sharing best practices for improving outcomes. Each will be discussed in turn. Nursing leaders at participating facilities have used the information to advocate for more staff...

To date the NDNQI has already developed a number of standards. Four of the 15 standard nursing measures endorsed by the NQF have been NDNQI measures. Thirteen indicators already have been implemented in NDNQI, and at the time of this writing three additional measures, which are also NQF-endorsed measures, are scheduled for implementation. Of the 13 implemented indicators, eight are NQF consensus measures. NQF uses a consensus process to endorse measures. This process includes (a) consensus standard development, (b) widespread review, (c) member voting and member council approval, (d) board of directors action, and (e) evaluation. The importance of the NQF-endorsed indicators is that they provide a standard measure for evaluating nursing care and are the only nursing measures that have been endorsed for public reporting.

Data training procedures and submissions have advanced from a telephone call for 1:1 training and submission using a CD, to use of comprehensive, web-based tutorials training participants to submit data using electronic means. Data submission now involves specification of unit types and various patient types, such as adult, pediatric, neonatal, psychiatric, and rehabilitation patient populations.

Research on the database has yielded meaningful information on both workforce characteristics which influence quality outcomes and the importance of evaluating the data based on unit type. Identification of important correlations between structures and processes and observed nursing outcomes can help facilities improve their nursing care outcomes.Dunton et al. (2004) evaluated nurse staffing and patient falls and noted important correlations. They observed that lower fall rates were associated with higher staffing on certain types of units, and noted a strong relationship between fall rates, nursing hours, and skill mix. Hart, et al.(2006) studied the incidence of pressure ulcers among NDNQI hospitals, and reported a difference in quality outcomes based on the nursing workforce element of certification. As a result of the Hart et al. study an additional, web-based tutorial on pressure ulcers was created by NDNQI to educate the staff nurse on wound assessment. It is available publicly on the NDNQI web-site for any nurse to complete. Both of these studies demonstrated the value of reporting nursing-sensitive indicator data at the unit level, recognizing that variability of outcomes occurs at the unit level based on patient type, nurse staffing, and the nursing workforce characteristics. The NDNQI database enables researchers to identify various nursing workforce elements that can impact patient outcome, such as nurse staffing, skill mix, and specific nursing processes. It also enables researchers to identify process elements that can influence patient outcomes. Identification of important correlations between structures and processes and observed nursing outcomes can help facilities improve their nursing care outcomes. The database provides the end user with a powerful tool to aid in decision making related to improving the nursing work environment and patient outcomes.

...80% of NDNQI-participating facilities join because they believe in the value of evaluating the quality of nursing care and improving outcomes, activities which are both basic responsibilities of the profession. NDNQI staff have also helped facilities improve patient care by sharing best practices. In 2006 NDNQI staff identified facilities that had sustained an improvement in a given nursing-sensitive indicator. These facilities were asked to share what they had done to bring about this improvement. Fourteen facilities were profiled in a monograph identifying their experience with the database, their use of the data, and improvement strategies they had implemented to improve nursing performance in a given measure (Montalvo & Dunton, 2007). For example, in one facility the hospital-acquired pressure ulcer (HAPU) rate dropped from 6.31 to 3.04 after implementing a quality improvement process that included assigning wound/ostomy/ continence specialists to specific nursing units to help all staff improve their surveillance for HAPUs and adopt a zero tolerance for HAPU. The opportunity for varying-size facilities to share these best practices adds to nursing's knowledge base and helps nurses nation wide to improve nursing practice and patient outcome. The First Annual NDNQI Data Use Conference was held in January 2007 and was highly successful with 900 attendees being able to walk away with practical tools and tips in utilizing NDNQI data and to improve nursing-sensitive indicator outcomes. The monograph by Montalvo and Dunton, along with the annual national conference, have aided in disseminating such helpful information to all interested parties.

The current consumer-driven health care environment requires accountability for the health care decisions made and the impact of these decisions on patients. Although direct financial cost/benefits have not been fully calculated with NDNQI globally, the staff nurses and nurse leaders now have a valuable nursing tool to aid them in decision making about staffing, skill mix, patient care processes, and workforce characteristics that affect patient outcomes, thus influencing directly and indirectly the cost of patient care. The facility now has the data necessary to calculate their cost/benefit ratio based on their improvements and outcomes.

Future Plans and Goals for NDNQI®

The NDNQI database continues to grow in the number of facilities participating and in methodological sophistication. The database has grown from the original 30 facilities to over 1100 facilities in 2007, and ongoing investment and database enhancements continue. Two key developments are slated to begin in 2007. One is to develop methods for measuring unit-level acuity. This will provide mixed acuity units (units having more than 10% of patients representing a different patient population, such as rehabilitation patients on medical units [NDNQI operational definition, 2007]) and universal bed units (those having patient rooms equipped to care for any patient regardless of acuity [Brown, 2007]) with the ability to receive comparisons from NDNQI.

The second enhancement is to improve reporting features of NDNQI, so that more finite or granular comparisons of a very specific type of unit can be made. An example of a more finite comparison for particular facilities would be comparing coronary critical care units in the 100-bed to 199-bed hospitals. More enhanced reporting will provide more specific comparisons, the ability to download and post different sections of the report, new color graphics, single report cards, and hospital-level summaries. These value-added enhancements will provide the end user with a more powerful tool to evaluate nursing care, improve quality, and influence outcomes for both the patient and the nursing staff alike.

New indicators are added to the database on an annual basis. Additionally, over the next 18 months, existing indicators in the database will become available for all appropriate nursing units. For example, the current psychiatric assault indicator could be pertinent in the Emergency Department (ED) because the ED is a point of entry for these patients. As the demand for data increases, expanding existing indicators to relevant areas will facilitate the ability of facilities to respond to patient and staff needs.

Researchers will also continue to benefit from these enhancements. These developments will enable researchers to fine-tune their research questions and identify additional associations between nursing workforce characteristics and processes and the observed patient outcomes.

Conclusion

The NDNQI has made considerable progress since the ANA Board of Directors asked ANA staff to investigate the impact of workforce restructuring and redesign on patient care and to quantify the relationship between nurse staffing and patient outcomes. Today's national spotlights on patient safety and public reporting have increased the need for nursing to collect and monitor data related to patient outcomes. It is also critical to continue these efforts to ensure nursing has the appropriate workforce to render the care necessary to optimize patient outcomes at the unit level. NDNQI studies have demonstrated the value of nursing care and the significance of nursing's contribution to positive patient outcomes. NDNQI data now has the validity and reliability to be used to evaluate nursing care, improve patient outcomes, and identify the linkages between nurse staffing and patient outcomes at the unit level. NDNQI has indeed become the seminal nursing database that is used to influence nursing policy and improve nursing care.

Author

Isis Montalvo, MS, MBA, RN

Email: Isis.Montalvo@ana.org

Isis Montalvo is Manager, Nursing Practice & Policy at the American Nurses Association (ANA). She is primarily responsible for providing oversight to the National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators™ (NDNQI®) in which over 1100 hospitals currently participate (www.nursingquality.org). Ms. Montalvo has over 20 years experience in multiple areas of clinical and administrative practice with a focus in critical care and performance improvement. As a former NDNQI Site Coordinator, Quality Specialist, and Nursing Research Chair at a large urban facility she brings expertise in data analysis, performance improvement, and nursing care evaluation. In 1996, she received her Master’s in Business Administration from the University of Baltimore in Maryland and her Master’s of Science in Nursing Administration from the University of Maryland . She is a Critical Care Registered Nurse (CCRN) Alumnus and a member of the American Association of Critical Care Nurses, the American Society of Association Executives/The Center for Association Leadership, the National Association for Healthcare Quality, and Phi Kappa Phi and Sigma Theta Tau honor societies.

References

American Nurses Association. (1995). Nursings report card for acute care. Washington, DC: American Nurses Publishing.

American Nurses Association. (1996a). Nursing quality indicators: Definitions and implications Washington, DC: American Nurses Publishing. Available: www.nursingworld.org/books/pdescr.cfm?cnum=11#NP-108

American Nurses Association. (1996b). Nursing quality indicators: Guide for implementation. Washington, DC: American Nurses Publishing.

American Nurses Association. (1997). Implementing nursings report card: A study of RN staffing, length of stay and patient outcomes. Washington, DC: American Nurses Publishing.

American Nurses Association. (1999). Nursing quality indicators: Guide for implementation (2nd Ed.) Washington, DC: American Nurses Publishing. Available: www.nursingworld.org/books/pdescr.cfm?cnum=11#9906GI

American Nurses Association. (2000a). Nursing quality indicators beyond acute care: Literature review. Washington, DC: American Nurses Publishing

American Nurses Association. (2000b). Nursing quality indicators beyond acute care: Measurement instruments. Washington, DC: American Nurses Publishing

American Nurses Association. (2000c). Nurse staffing and patient outcomes. Washington, DC: American Nurses Publishing

American Nurses Association. (2001). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretative statements. Washington, DC: American Nurses Publishing, pg 12.

American Nurse Association. (2004). Nursing: Scope & standards of practice. Silver Spring, MD: nursesbooks.org.

American Nurses Association. (2005). Utilization guide for the ANA principles for nurse staffing. Silver Spring, MD: nursesbooks.org.

Brown, K.K. (2007, March/April) The universal bed care delivery model. Patient Safety and Quality Health Care. Retrieved, August 19, 2007 from www.psqh.com/marapr07/caredelivery.html

Dossey, B.M., Selanders, L.C., Beck D.M., & Attewell, A. (2005). Florence Nightingale today: Healing, leadership, global action. Silver Spring, MD: Nursesbooks.org. Available: www.nursingworld.org/books/pdescr.cfm?cnum=29#04FNT

Donabedian A. (1988). The quality of care: How can it be assessed? JAMA, 260,1743-1748.

Donabedian, A. (1992). The role of outcomes in quality assessment and assurance. Quality Review Bulletin, 11, 356-60.

Dunton, N., Gajewski, B., Taunton, R.L., & Moore, J. (2004). Nurse staffing and patient falls on acute care hospital units. Nurse Outlook, 52, 53-9.

Gajewski, B., Hart, S., Bergquist-Beringer, S., & Dunton, N. (2007). Inter-rater reliability of pressure ulcer staging: Ordinal probit Bayesian hierarchical model that allows for uncertain rater response. Statistics in Medicine (in press).

Gallagher, R.M. & Rowell, P.A. (2003). Claiming the future of nursing through nursing-sensitive quality indicators. Nursing Administration Quarterly 24(4), 273-284.

Hart, S., Berquist, S., Gajewski, B., & Dunton, N. (2006). Reliability testing of the National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators pressure ulcer indicator. Journal of Nursing Care Quality 21(3), 256-265.

Institute of Medicine. (1999). To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Institute of Medicine. (2001). Crossing the quality chasm. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Institute of Medicine. (2005). Performance measurement: Accelerating improvement. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Kurtzman, E.T., & Corrigan, J.M. (2007). Measuring the contribution of nursing to quality, patient safety, and health care outcomes. Policy, Politics & Nursing Practice, 8(1), 20-36.

Montalvo, I., & Dunton, N. (2007). Transforming nursing data into quality care: Profiles of quality improvement in U.S. healthcare facilities. Silver Spring, MD: Nursesbooks.org.

Nightingale, F. (1859; reprinted 1946). Notes on nursing: What it is, and what it is not. Philadelphia: Edward Stern & Company.

Rantz, M. (1995). Nursing quality measurement: A review of nursing studies. Washington, DC: American Nurses Publishing. Available: www.nursingworld.org/books/pdescr.cfm?cnum=11#NQM22

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. (2007, May 30). Interdisciplinary nursing quality research initiative. (INQRI). Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Retrieved, May 31, 2007 from www.inqri.org/ProgramOverview.html

The Joint Commission. (2007, May 27).. Performance measurement initiatives. The Joint Commission. Retrieved May 27, 2007, from www.jointcommission.org/PerformanceMeasurement/PerformanceMeasurement/