To provide holistic care that addresses all aspects of patient needs, nurses must understand the complexities of healthcare for the large population of people who live in poverty. The World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes the Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) as individual income, living conditions, social supports, and access to adequate food sources, education, and healthcare. Eighty percent of a person’s ability to attain health and well-being is related to the SDOH. In the United States, Healthy People 2030 and accrediting bodies for professional nursing programs focus on the SDOH and the impact of these determinants on health equity and access to care. Thus, as nursing students learn about challenges faced by persons who live in poverty conditions, it can be beneficial to also experience what their everyday life entails. One option available is the use of poverty simulation tools. This article provides an overview of the Missouri Community Action Network Community Action Poverty Simulation (CAPS) used in a Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) curriculum to enhance student understanding about the experiences of living in poverty, to increase their ability to analyze the relationship between the SDOH and poor health outcomes, and to identify potential personal attitudes and biases. We offer information about our experiences with poverty simulation planning, implementation, and evaluation.

Key Words: Social Determinants of Health (SDOH), Healthy People 2030, poverty simulation, health equity, poverty, teaching SDOH, embedding SDOH into curriculum, nursing empathy

Social determinants of health impact 80% of people's ability to attain health and well-being, quality of life, and access to care...Defined by the World Health Organization as “non-medical factors that influence health outcomes” ([WHO], n.d., para. 1), the social determinants of health (SDOH) include economic stability, neighborhood and environment, social and community resources, and access to quality education and healthcare. Social determinants of health impact 80% of people's ability to attain health and well-being, quality of life, and access to care (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2023). Many vulnerable populations experience not one, but all, of these SDOH factors.

Healthy People 2030 is the United States Department of Health and Human Services (U.S. DHHS) guide to addressing the health and well-being of the nation (U.S. DHHS Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion [ODPHP], 2020). Beginning in 1990, the ODPHP started gathering data, setting goals, and working to help Americans live longer, healthier lives through a 10-year Healthy People initiative. Successful initiatives have included reduction of deaths related to heart disease and cancer, increased childhood vaccination rates, and public knowledge of preventable risk factors such as smoking, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol (U.S. DHHS, 2021). However, decreasing health disparities and achieving health equity remain unmet goals of Healthy People 2000 and have become key focus areas for Healthy People 2030.

The overarching goal of Healthy People 2030 is to improve the health and well-being of all people and ensure that individuals have the knowledge, resources, and ability to reach their full health potential (U.S. DHHS, 2020). Five key areas comprise the Healthy People 2030 framework: health disparities, health equity, health literacy, well-being, and the SDOH. Health disparities encompass individual or population differences related to social, economic, or environmental disadvantages. Health equity is the ability for all individuals to achieve their greatest level of health. An expansion of health equity, health literacy, includes both individuals and organizations. Individual health literacy is the ability for individuals to understand health-related information to guide decision-making. Organizational health literacy is the organization level responsibility to provide health information accessible to all individuals, regardless of education, age, or disability. Well-being, according to Healthy People 2030, is the individual's perceived level of satisfaction in life. As the final key element of Healthy People 2030, the SDOH influence each of the other key areas and impact achievement of health equity and health outcomes.

For persons who live in poverty, surviving day to day is prioritized over health-seeking behaviors.Nearly 38 million Americans live in poverty; 15 million are children (U.S. Census Bureau, 2023). Poverty significantly impacts SDOH, health equity and literacy, and personal well-being. People living in poverty lack financial security and may live in under resourced neighborhoods with exposure to illicit drug use and violence, attend lower performing schools, lack access to nutritious food and have limited social supports. (HealthyPeople.gov, n.d.) This lack of resources can lead to higher risks to develop mental illness and chronic illnesses that further negatively impact their well-being and health outcomes (U.S. DHHS, n.d.). For persons who live in poverty, surviving day to day is prioritized over health-seeking behaviors.

As members of the largest and most trusted healthcare profession, nurses are positioned to address the key areas of Healthy People 2030 through education, advocacy, and commitment to patient health. Both primary nursing accreditation bodies, the Accreditation Commission of Education in Nursing (ACEN) and the American Association of Colleges of Nursing Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education (AACN/CCNE), require nursing competency in diversity and equity. For example, AACN (2021) has recently updated the required standards for the Bachelor of Science degree in nursing based on the increasing complexities in healthcare and recent reports of novice nurses who lack of readiness to practice (Kavanagh & Sharpnack, 2021; Kavanagh & Szweda, 2017). The updated 2021 AACN accreditation competencies are more explicit and include a requirement for competency in applying knowledge, skills, and attitudes of SDOH and diversity, equity, and inclusion throughout nursing curricula at all levels and across the lifespan. This article discusses one way to help students to better understand the challenges of persons living in poverty conditions from the lens of the SDOH through the use of a poverty simulation.

Brief Review of Literature

The nurses also lacked insight into how they could become involved in changing hospital, local, and national policies...Schneiderman and Olshansky (2021) completed a qualitative study that focused on how nurses use SDOH in practice. The participants, 13 practicing baccalaureate-prepared registered nurses (RNs) beginning a family nurse practitioner program, were asked about their understanding of how SDOH impacts patient outcomes. Two themes emerged from the study: (1) nurses do integrate SDOH into their care; and (2) healthcare delivery needs to change to address health equity and access to care for those in need. While the nurses reported integrating SDOH into their care, they also noted frustration with understanding how patients navigated, or chose not to use the resources available to them, to improve their SDOH. The nurses also lacked insight into how they could become involved in changing hospital, local, and national policies regarding Healthy People 2030 initiatives.

Thornton and Persaud (2018) identified the need to include SDOH education into nursing curricula to prepare graduates to address health literacy and equity issues. Content to prepare nursing students to recognize and address challenges faced by individuals’ experiences related to SDOH and advocate for change should be woven throughout nursing curricula across the lifespan and in a variety of settings, both acute and community. Didactic teaching alone may increase biases; therefore, experiential training is essential. Along with didactic teaching, interprofessional education and simulation experiences can help to prepare students to address SDOH (Thornton & Persaud, 2018).

Lee and Wilson (2020) found that new nursing students attribute an individual’s health status to life choices, such as smoking and poor diet. After participating in a poverty simulation, students identified how SDOH can impact health and access to healthcare. Students also noted the role and responsibility of nurses to advocate for changes to improve the health and wellbeing of all individuals and the role that the profession of nursing as a whole must play to improve health outcomes.

Incorporating the SDOH into Curricula

To prepare nursing students to provide care that supports health equity and literacy, and to address accreditation requirements that support Healthy People 2030 (U.S. DHHS, 2020) initiatives, nurse educators at Kent State University (and in many other programs) embed SDOH throughout the nursing curricula. For example, the SDOH concept is first introduced in didactic nursing courses, and then students begin to identify the SDOH in case studies and address how individual patients’ SDOH impact care during clinical experiences. The Healthcare Policy course focuses on SDOH through the lens of policy development and the nurse advocacy role. During the senior year, students in the Community Health Nursing course have the opportunity to analyze the SDOH, their impact at the population level, and their role in the delivery of healthcare by experiencing a poverty simulation.

Poverty simulations help nursing students understand the lived experiences of impoverished persons.Simulations are essential educational tools designed to expose nursing students to real-life scenarios. Most nursing simulations are based on clinical competencies, allowing students to experience real-life scenarios, learn from mistakes (without harming a person), and reflect in a safe learning environment (Lavoie & Clarke, 2017). Poverty simulations help nursing students understand the lived experiences of impoverished persons. Because poverty simulations compel students to prioritize paying bills, rent, childcare, and other expenses, they provide a safe space for students to learn about factors that can lead to lack of compliance and health-seeking behaviors that people living in poverty often exhibit.

The Poverty Simulation

Several major poverty simulation kits are available. The two most notable are the Missouri Community Action Network Community Action Poverty Simulation (CAPS) and the ThinkTank (n.d.) The Cost of Poverty Experience [COPE]. The COPE focuses on the experiences of students aged 16-24 while the CAPS covers experiences ranging from pregnant teenagers to older adults with a diverse range of family situations. Additionally, over 100 people can participate in the CAPS simulation playing various roles. For these reasons, the nursing faculty at Kent State University chose the CAPS poverty simulation.

Design and Plan for Implementation

The CAPS experience assigns individuals (in this case, students) to play various family members, community resource personnel, and service roles. Family situations range from those who are homeless, newly unemployed, or employed but in need of supplemental income. All families must provide for necessities, pay bills, take care of their children, and maintain shelter during the course of four 15-minute “weeks.”

Family situations range from those who are homeless, newly unemployed, or employed but in need of supplemental income.The simulation is ideally conducted in a large room with families’ “homes” in the center of the room and community resources and services around the perimeter. Services and resources include a bank, supercenter, community action agency, employer, utility company, pawn broker, grocery, social service agency, faith-based agency, payday and title loan facility, mortgage company, school, community health center physician, public health caseworker, and childcare center. The simulation lasts about two hours and includes an introduction, pre-briefing, simulation weeks, and debriefing session.

The primary objective of the CAPS is to “sensitize participants to the day-to-day realities of life faced by people with low incomes and to build empathy and motivate participants to become involved in activities which help to reduce poverty in this country” (Missouri Community Action Agency, 2021, p. 18). Learning outcomes for the CAPS experience include students’ ability to:

- Demonstrate an understanding of the unique situational needs of people with lower socioeconomic status through playing their role in the simulation.

- Through reflection, identify personal attitudes, feelings, and associated changes regarding the care of low-income and/or vulnerable families like those portrayed in the simulation.

- Analyze the relationship between social determinants of health and poor health outcomes of impoverished persons.

- Evaluate ways the fictional simulation community structure relates to realistic scenarios.

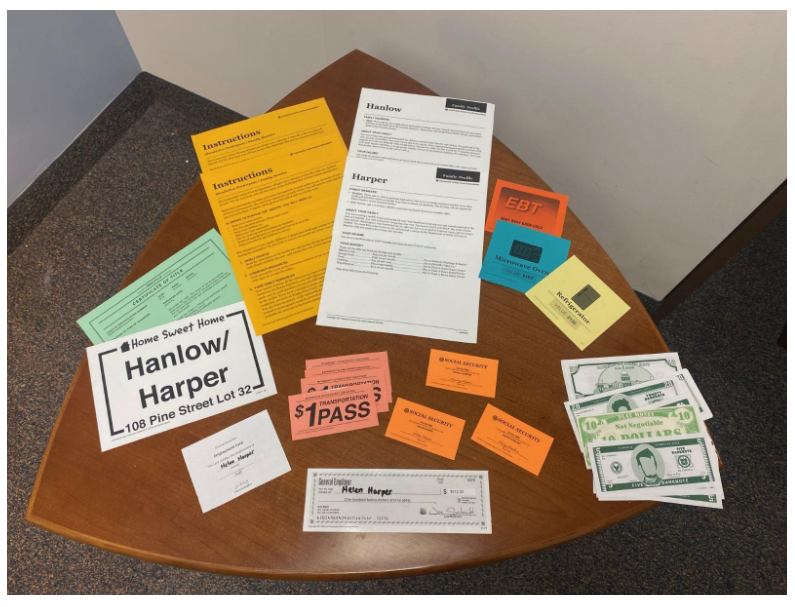

Family and community resource props illustrate a complete picture of hardships encountered by families with lower incomes.Each CAPS kit contains everything needed to run the simulation, including a large binder with instructions, name badges for volunteers and participants, and a packet for each family and community role with instructions and props (see Figure 1). Family and community resource props illustrate a complete picture of hardships encountered by families with lower incomes. Unknown to students, scenarios are based on real clients from the Missouri Community Action Network. Sometimes resembling game pieces, props are designed to give participants a more realistic experience interacting with and exchanging physical items (e.g., money, checks, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program [SNAP] benefits, vouchers) as opposed to the more abstract experience of imagining these concepts.

Figure 1. Simulation Example Pieces

(Missouri Community Action Network, 2021. Used with permission).

Simulation Timeline

Planning and preparing to launch a poverty simulation is critical to its success.Planning and preparing to launch a poverty simulation is critical to its success. To learn how to facilitate the simulation, virtual and in-person training sessions are available. Unfortunately, training sessions were suspended during the COVID-19 pandemic, so the faculty leader collaborated with area community leaders serving in local housing and urban development and a healthcare partner with experience implementing the simulation to review the Missouri Community Action Network facilitator manual. The facilitator manual includes simulated family backgrounds, community resource roles, the debriefing plan, and how to develop a timeline of responsibilities. The timeline for preparation that we used is illustrated below in the Table.

Table. Simulation Timeline

|

Several Months Prior to Event |

|

|

Six Weeks Before Event |

|

|

Simulation Preparation Meeting |

|

|

Simulation Day |

|

Meeting the Standard of Best Practice

Pre-briefing for Healthcare Simulation:

For the first poverty simulation, students were assigned roles at random as they arrived at the conference center. The facilitator explained how the simulation would progress and students’ responsibilities. Students were given 10-15 minutes to review the information packets and ask questions. In subsequent simulations, we revised preparation for faculty and students. Participants were assigned roles a week in advance and basic information was communicated before the day of simulation.

Concerns were raised regarding retraumatizing students who may have had life experiences mirroring those portrayed in the simulation. To create a safe space, the facilitator announced prior to the simulation that students had permission to excuse themselves during the simulation to a quiet office or hall with the opportunity to meet with faculty, if needed. Poverty simulations are intentionally chaotic, so a quiet exit is not likely to be noticed. The student is then instructed to return at a designated time before the simulation ends to lessen the chance that their return will be noticed.

The Simulation Experience

After participants reviewed their roles and the content of their family packets (Figure 1) and familiarized themselves with the rules, the facilitator blew a whistle (or other tone) to designate the start of the first “week” of the poverty simulation. Participants had 15 minutes to accomplish all tasks, including any additional tasks issued by the facilitator or another volunteer. School-aged participants attended school while the rest of the family went to work and paid bills.

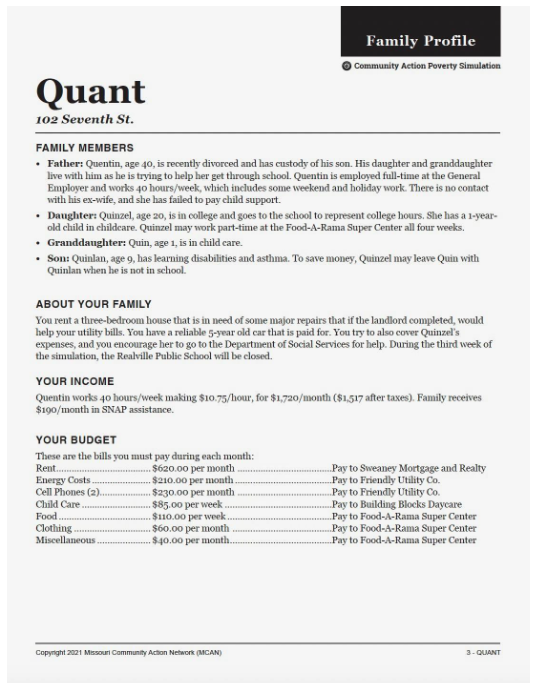

The family profile for the Quant family (Figure 2) provides an example. After the facilitator blows the whistle, Quentin, the head of this household, must go to the employer within three minutes and stay there for eight minutes in order to get paid for the week. Quinzel, Quentin’s daughter, must first drop her child off at the daycare center, pay the daycare $85, arrive at the employer within three minutes, and stay at work for at least four minutes for her part-time position. Nine-year-old Quinlan goes to the school, stays there for eight minutes, and then goes back to the family base.

The adults in this household, Quentin and Quinzel, must spend the remainder of their time paying bills that are due for the week and strategizing how and when to pay the monthly bills, knowing that each time they visit a community site, they must present a $1 pass (see Figure 1). When the facilitator blows the whistle signifying the end of the week, participants must immediately stop what they are doing and return to their family seats. Even if a participant is in the process of making a transaction, if the transaction is not complete prior to the whistle blowing, they have not paid their bill which is now considered past due. Participants play their various assigned family roles for each 15-minute session.

Figure 2. Quant Family Profile

(Missouri Community Action Network, 2021. Used with permission).

Each family must consider many factors to survive the month.Each family must consider many factors to survive the month. The majority of families portrayed in the simulation do not make enough money to pay their bills, so participants must decide which to pay and which to skip. Volunteers portraying community roles are encouraged to be very strict. If a participant does not pay rent, the realtor will evict them. If a participant does not pay utility bills, the utilities will be shut off. In the case of the Quant family, if law enforcement discovers a one-year-old in the care of a nine-year-old disabled child, both will be taken to child protective custody. “Luck of the draw” cards are presented randomly to participants by the facilitator representing unexpected events that can either positively or negatively affect the participant, such as winning the lottery or breaking a bone.

Debriefing and Student Reflection

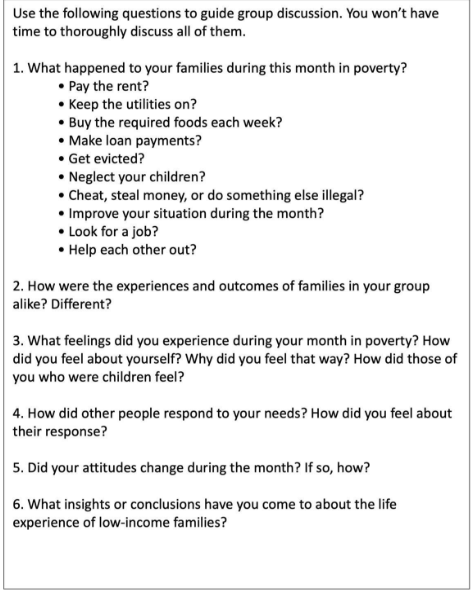

...participants are encouraged to share their insights, experiences, and feelingsAfter the poverty simulation “month” concludes, there is a debriefing session utilizing the Debriefing for Cultural Humility© method (Foronda, 2021). This method involves acknowledging how learners feel, identifying how they were treated (or treated others) in the context of the experience, and analyzing outcomes including acknowledgement of power imbalances (Foronda, 2021). As the facilitator asks group debriefing questions (see Figure 3), participants are encouraged to share their insights, experiences, and feelings. Questions follow a four-phase format that encompasses reactions, descriptions, analysis, and summarization. Along with encouraging students to share their experiences, the facilitator asks faculty to provide objective observations to further the discussion.

Figure 3. Sample Group Discussion

(Missouri Community Action Network, 2021. Used with permission)

They also highlight how the simulation increases their empathy toward persons who live in poverty.Debriefing sessions for a large group can be challenging as not every student has a chance to speak. In our experience, each debriefing session has had a similar outcome: students discuss the stress of the family situations (among other feelings), frustrations in dealing with difficult community situations, and relief they feel when the simulation is completed. They also highlight how the simulation increases their empathy toward persons who live in poverty. At every debriefing session, at least one student has shared personal life experiences with poverty similar to those portrayed in the simulation.

One week after the poverty simulation, students submitted a personal reflection about the experience. This offered them additional reflection time and an opportunity to express thoughts they may not have felt comfortable sharing in front of a large group. Our reflection assignment is open-ended without a length requirement. Students are asked to respond to five questions, as follows:

- What happened to your “family” during this month in poverty?

- What feelings did you experience during your month in poverty?

- How did other people respond to your needs and how did you feel about their responses?

- Did your attitudes change during the month and how?

- After participating in the simulation, what insights or conclusions have you come to about the life experiences of low-income families?

Faculty reviewed each student’s reflection. We provided feedback to support understanding of how SDOH can affect individual or family motivation to make healthy choices and seek access to care.

Evaluation of the Poverty Simulation

Evaluation in nursing education is a systematic process. We assess effectiveness, efficiency, and quality to prepare competent and capable nurses who can provide safe, high-quality patient care in a dynamic healthcare environment (Lewallen, 2015). Evaluation involves collecting and analyzing data to determine if objectives for an activity were met and if not, to identify areas for improvement. Our evaluation of the poverty simulation was conducted in the context of review of the effectiveness of a pedagogical strategy, and not as a research study. We used the reflective journal entries to evaluate the effectiveness of the poverty simulation related to the established learning outcomes.

Learning outcome #1: Students will demonstrate an understanding of the unique situational needs of people with lower socioeconomic status through playing their role in the simulation.

This goal was met in two ways. First, students participated in the simulation to the best of their abilities and understanding. This was true even for the students who “gave up” as their family situations deteriorated. Secondly, during debriefing and reflection, students showed their understanding of SDOH with various statements regarding feeling trapped with insurmountable obstacles to overcome. For example, one student stated, “[People living in poverty] are often . . .down and can’t rise above their circumstances without an egregious and disproportionate amount of work that isn’t required or expected from individuals born into better circumstances.”

Learning outcome #2: Students will, through reflection, identify personal attitudes, feelings, and associated changes regarding the care of low-income and/or vulnerable families like those portrayed in the simulation.

Most students described the simulation as eye-opening...Data from student reflections demonstrates their wide range of feelings toward people living in poverty. Students reported emotions they experienced during and after the simulation. The most common feeling reported was stress, followed by frustration, anger, and hopelessness. Most students described the simulation as eye-opening and increased their empathy toward people who live in poverty conditions.

Learning outcome #3: Analyze the relationship between social determinants of health and poor health outcomes of impoverished persons.

The poverty simulation facilitated a deeper understanding of the interrelated nature of SDOH. While most students did not use the phrase “social determinant,” language from their reflections demonstrated this learning. One student captured it well by stating,

After participating in the simulation, I have recognized that low-income families have many added stressors in their lives that may greatly contribute to the development of chronic diseases and a lower life expectancy such as the inability to find employment, pay bills, afford clothes and food, and get from place to place.

Access to Quality Education. Students playing the role of school-aged children understood that quality education is not just about access. One student noted that “Poverty seems to have an especially negative effect on children, because they seem to become increasingly apathetic about their education and health because they don’t have the same opportunities that middle- or high-income families have.” Even students who played teacher roles developed a deeper understanding; one stated,

In the first week, it was fun, and everyone showed up to class. After the first week, kids started slowly not coming back to school and I realized it was either because they needed help at home or got in trouble in some way.

Community Resources. Students demonstrated understanding of this SDOH when discussing transportation. They reflected on the stress of presenting transportation tickets when going from task to task as the weeks went on. For some students, understanding the cost of transportation deepened their sense of empathy the most because they perceived why those who lack reliable transportation are often late to class, work, or medical appointments. One student stated,

It is not lost upon me that the reality for low-income families is that they would not be simply running from room to room; they are running from bus stop to bus stop to get from one point of the city to the other.

Another student who played a community role commented,

During the first week, most of the children showed up but then after the second week only one child came back to the childcare center. All the other children never came back due to having to give up too many transportation tickets.

Access to Healthcare. While most students did not reference healthcare access in their reflections, they did talk about the relationship between socioeconomic status, stress, and development of chronic disease. What became clear during debriefing sessions is that while playing their roles within the simulation, students simply did not think about health issues faced by disadvantaged populations unless specifically directed to do so by a facilitator. Based on Maslow’s hierarchy (Maslow, 1943), this makes sense as perfectly illustrated by one student’s reflection:

I played the role of the physician at the community health center. The participants did not come to the community health center often. I realized that they put the health of their family low on their list of priorities. Throughout the month, the participants began to visit me more often because the case management worker was giving out health notices to the families, so they were really pushed to visit the community health center. However, even if some families got health notices like they had a bad toothache, they still choose to not come to the health center.

As the simulation progressed, the most reported change in attitude was a move away from optimism toward defeat, desperation, and even hostility.Social Support/Community Context and Economic Stability. The poverty simulation was an excellent opportunity to instruct students about the last two determinants. As the simulation progressed, the most reported change in attitude was a move away from optimism toward defeat, desperation, and even hostility. As student participants lost jobs, became homeless, or fell ill, their fictional family relationships suffered. Even when resources were available, accessing them was not straightforward or timely. In a short period of time, students understood why some citizens turn to crime, and once in the system, they cannot get out of it. Students also understood that poverty is generational and not just a result of one person’s choices. Poverty presents a set of challenges that are often beyond one’s control.

Learning outcome #4: Evaluate ways the fictional simulation community structure relates to real life scenarios.

Students demonstrated understanding through discussion of issues related to transportation and how the simulation showcased the chaos that people living in poverty experience. One student stated,

At first, the poverty simulation could have been more straightforward . . . which, as the experience went on, I realized was done purposely. Low-income families need more guidance on where to go, what to do, and what resources are available.

Another student noted that “Although this was a made-up scenario, this is someone’s life in the world.”

Limitations

Our educational program level evaluation was guided by the simulation outcomes. More formal studies using tools that are both valid and reliable are needed. Gathering demographic data, such as age, gender, and socioeconomic status of the participants may show differences in the effects of the simulation in relation to empathy and understanding health equity. Also, while program evaluation focuses on short-term outcomes in an educational setting, longitudinal studies would be beneficial to determine whether poverty simulations as a pedagogical strategy actually impact nursing practice over time.

Discussion

The goal for poverty simulation is...for [students] to consider what they can do to help as healthcare providers.The goal for poverty simulation is not only for students to understand what contributes to the poverty cycle, but to also for them to consider what they can do to help as healthcare providers. Nursing curricula have historically been required to include the concepts of community, health and wellness, and safety. However, until recently, there has been less focus on access to care and health equity for underserved populations. Accrediting bodies for nursing education programs require that content in curricula leads to competency in learning and applying the SDOH, diversity, equity and inclusion across the lifespan (AACN, 2021). Real-life experiences offered by the experience of a poverty simulation helps participants to understand challenges faced by marginalized, disadvantaged populations. Participants can develop both empathy and a desire to advocate for better resources and a more focused approach to health access and literacy.

Information about our experiences adds to the ongoing discussion regarding the usefulness of incorporating poverty simulations into nursing curricula. Some may argue that there are alternative methods for teaching about SDOH and healthcare disparities. Alternative strategies such as case studies, community-based learning experiences, or other forms of interactive education could have other benefits for participants and/or address concerns related to use of a simulation with the potential for student distress. We respond that the immersive nature of simulations offers a unique and impactful way to convey the nuances of poverty and inequality. It is best practice for any simulation to have a plan for students to debrief, and that includes the distress and feelings experienced during the simulation time. In essence, the ongoing debate reflects differing perspectives on the pedagogical value, ethical considerations, and long-term impact of poverty simulations in allied health classrooms. Researchers, educators, and practitioners continue to explore these issues to determine the most effective and ethical ways to address learning about the SDOH in healthcare education.

Conclusion

...poverty simulations can be an effective tool for many programs to provide experiential learning experiences...Nursing program accreditation standards require inclusion of SDOH concepts throughout the curriculum at all levels of nursing education (AACN, 2021). As the largest group of healthcare providers, nurses are positioned to help the United States of America finally reach the Healthy People 2030 (U.S. DHHS, 2020) goal of health equity by addressing the health disparities of people who live in poverty. While poverty simulation experiences may trigger past emotions, this is similar to end-of-life, mock codes, or mental health simulations. Pre-briefing, participant permission, and a plan to step away have been effective tools to mitigate participant distress. To date, 423 students have completed our poverty simulation without evidence of apparent undue harm. In sum, poverty simulations can be an effective tool for many programs to provide experiential learning experiences for nursing students and other healthcare professionals to gain a greater understanding of SDOH challenges and barriers to health access and equity.

Authors

Tracey Motter, DNP, MSN, RN

Email: tmotter2@kent.edu

ORCID ID: 0000-0002-3573-937X

Tracey is the Associate Dean of Academics at Kent State University College of Nursing. She earned a BSN from Duquesne University, an MSN from Gannon University, and a DNP from Kent State University. Her research areas of interest include health equity, transition to practice, and preparation of nurse leaders to provide quality, cost-effective healthcare.

Taryn Burhanna, MSN, APRN, NP-C

Email: tburhann@kent.edu

Taryn is a Lecturer and Clinical Instructor at Kent State University College of Nursing. She is also a primary care nurse practitioner at a federally qualified healthcare center. Her areas of interest are population health nursing, vulnerable population advocacy, and primary care.

Jennifer Metheney, MSN, RN, CNE

Email: jmethene@kent.edu

Jennifer serves as a Senior Lecturer for Kent State University College of Nursing with specialty areas in geriatrics, chronic illness, and rehabilitation/disability. Her 17 years of teaching include the Community Health Nursing course which promotes skill development through clinical simulation. She earned a BSN from Alderson-Broaddus College and an MSN with a concentration as a Clinical Nurse Specialist, Geriatrics from Kent State University.

References

American Association of the Colleges of Nursing. (2021). The essentials: Core competencies for professional nursing education. https://www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Publications/Essentials-2021.pdf

Foronda, C. (2021). Debriefing for cultural humility. Nurse Educator, 46(5), 268-270. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNE.0000000000000957

HealthyPeople.gov. (n.d.). Healthy people 202: social determinants of health. https://wayback.archive-it.org/5774/20220413203948/https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health

Kavanagh, J. M. & Sharpnack, P. A. (January 31, 2021). Crisis in competency: A defining moment in nursing education. OJIN: The Online Journal of Nursing Issues, 26(1). https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol26No01Man02

Kavanagh, J. M., & Szweda C. (2017). A crisis in competency: The strategic and ethical imperative to assessing new graduate nurses' clinical reasoning. Nursing Education Perspectives, 38(2), 57-61. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NEP.0000000000000112

Lavoie, P., & Clarke, S. P. (2017). Simulation in nursing education. Nursing, 47(7), 18-20. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nurse.0000520520.99696.9a

Lee, S. K., & Wilson, P. (2020). Are nursing students learning about social determinants of health? Nursing Education Perspectives, 41(5), 201-29293. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NEP.0000000000000707

Lewallen, L. P. (2015). Practical strategies for nursing education program evaluation. Journal of Professional Nursing, 31(2), 133-140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2014.09.002

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054346

Missouri Community Action Network. (2021). Community action poverty simulation facilitator manual. https://www.communityaction.org/povertysimulations/

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. (2023). Medicaid's role in addressing social determinants of health. https://www.rwjf.org/en/insights/our-research/2019/02/medicaid-s-role-in-addressing-social-determinants-of-health.html

Schneiderman, J. U., & Olshansky, E. F. (2021). Nurses' perceptions: Addressing social determinants of health to improve patient outcomes. Nursing Forum, 56(2), 313-321. https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12549

ThinkTank. (n.d.). COPE: A ThinkTank experience. https://thinktank-inc.org/cope?gclid=EAIaIQobChMI0sG2-LfQggMVoEtHAR2cgw1PEAAYASAAEgJ0xfD_BwE

Thornton, M., & Persaud, S. (2018). Preparing today's nurses: Social determinants of health and nursing education. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 23(3). https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol23No03Man05

United States Census Bureau. (2023). National poverty in America awareness month: January 2023. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/stories/poverty-awareness-month.html

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2020). Healthy people 2030: Building a healthier future for all. https://health.gov/healthypeople

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2021). History of healthy people. https://health.gov/our-work/national-health-initiatives/healthy-people/about-healthy-people/history-healthy-people

World Health Organization [WHO]. (n.d.) Social determinants of health. https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1