A review of the literature on the health of nurses leaves little doubt that their work may take a toll on their psychosocial and physical health and well being.Nurses working in several specialty practice areas, such as intensive care, mental health, paediatrics, and oncology have been found to be particularly vulnerable to work-related stress. Several types of occupational stress have been identified, including burnout, compassion fatigue, and vicarious traumatization. While the emphasis of this article is on compassion fatigue and its theoretical conceptualization, the concepts of burnout and vicarious traumatization are also discussed. Two questions are posed for discussion: 1) Does compassion fatigue exist on a continuum of occupational stress? If so, is burnout a pre-condition for compassion fatigue; 2) What are the relationships between the types of occupational stress? To what extent does non-resolution of compassion fatigue increase the risk for developing vicarious traumatization? Case examples are provided to support this discussion.

Key words: burnout, compassion fatigue, occupational stress, stress continuum, vicarious traumatization

A review of the literature on the health of nurses leaves little doubt that their work may take a toll on their psychosocial and physical health and well being. Nurses working in several specialty practice areas, such as intensive care (Bakker, Le Blanc, & Schaufeli, 2005); mental health (Jenkins & Elliott, 2004), paediatrics; (Maytum, Bielski-Heiman, & Garwick, 2004); and oncology (Bakker, Fitch, Green, Butler, & Olsen, 2006; Ekedahl & Wengstrom, 2007), have been found to be particularly vulnerable to work-related stress. Researchers exploring the nature of occupational stress among care providers, including nurses, physicians, social workers, and psychologists, have suggested that aspects of the therapeutic relationship, specifically empathy and engagement, which are fundamental components of nursing, play a role in the onset of the stress. Further, non-relationship factors may also contribute to nurses experiencing a sense of ambiguity and/or conflict about their ability to provide the care they think is needed. These factors include increased patient complexity, reliance on advancing technology to sustain or prolong life, continued emphasis on medical models supporting cure over care, and perceived lack of time (Blomberg & Sahlberg-Blom, 2007; Edwards & Burnard, 2003; Ekedahl & Wengstrom, 2007; Hertting, 2003; Hertting, Nilsson, Theorell, & Larsson, 2004). It is possible that ongoing exposure to these factors may lead nurses to experience compassion fatigue, one form of occupational stress.

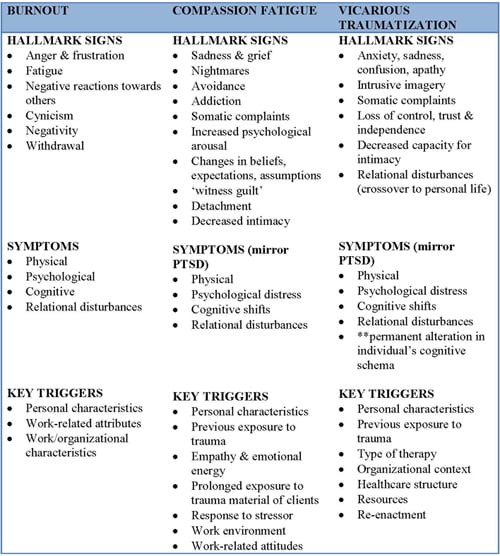

In this article I will provide an overview of the concepts of burnout, compassion fatigue, and vicarious traumatisation (see Table ). While emphasis is placed on compassion fatigue and its underlying theory, an overview of the other two types of occupational stress, namely burnout and vicarious traumatisation, are also provided. Following this overview I will address two questions: 1) Is compassion fatigue part of a continuum of occupations stress; if so, is burnout a precondition to compassion fatigue? and 2) What are the relationships between types of occupational stress and to what extent does non-resolution of compassion fatigue increase the risk for developing vicarious traumatization? I will provide three scenarios to address these questions and enhance the discussion.

Burnout

Research now supports six work-life issues involving person-job mismatch as the most likely explanation for burnout. Burnout has traditionally been rooted in an understanding of the interpersonal context of the job, specifically the relationship between caregivers and recipients of care and the values and beliefs pertaining to caring work held by care providers (Maslach, Schaufeli, & Leiter, 2001). It is most commonly defined as “a syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced accomplishments that can occur among individuals who do ‘people work’ of some kind” (Maslach & Jackson, 1986, p.1). Initially conceptualized to reflect the negative effects of people work, burnout has been expanded to include the negative effects of all occupations (Leiter & Schaufeli, 1996).

Possible factors leading to burnout can be classified according to personality characteristics, work-related attitudes, and work/organizational characteristics. Researchers have hypothesized three personality traits that contribute to burnout. They include type A personalities; coping styles, such as escape-avoidance, problem solving, and confrontation; and also traits sometimes referred to as the ‘big five,’ namely neuroticism, extroversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. However, the individual roles of these factors have yet to be fully explicated (Schaufeli & Enzmann, 1998). The big five is considered to be an empirical-based phenomenon describing personality traits rather than a theoretical model (Goldberg, 1990). These traits tend to occur in groupings in many individuals but are not always present together. It is conceivable that certain traits may predispose individuals to increased risk for the development of stress; however further research is necessary to demonstrate whether a causal link exists.

Work-related attitudes, such as the professional’s idealistic expectations, have been shown to influence the onset of burnout (Laschinger & Finegan, 2005; Leiter, 2005). For example, nurses’ expectation that providing a specific level of care will ultimately lead to positive outcomes for every patient is not only unrealistic and naïve, but may set nurses up for stress when they are unable to meet their expected goals. Further, incongruencies between nurses’ values and beliefs, which often include their philosophy of care/caring, and their organization’s vision and values (e.g., biomedical philosophy) may increase the potential for burnout.

Additional factors that may influence burnout include work-related and organizational characteristics. Examples include job-related stressors (e.g., increased patient-to-nurse ratios); client-related stressors (increased patient acuity and complexity); social support factors (amount of education and collaborative practice provided, and leader/peer support); and degree of autonomy (ability to retain control over decision making at the point of care and nurses’ input into changes related to unit-based care delivery within the nurses’ unit) within the work environment (Schaufeli & Enzmann, 1998). The first two factors (job-related and client-related) are associated with job demands whereas the latter two (social support and autonomy) are considered potential resources. For example, restructuring within healthcare institutions may result in nurses being moved from one service to another. The mistaken belief that a nurse is a nurse may result in the individual feeling increasing stress. When this shift takes place without adequate orientation and ongoing educational and resource support, the nurse may be at increased risk for experiencing burnout.

Although a number of theoretical frameworks have been proposed to explain burnout, including individual, interpersonal, organizational, and societal frameworks, research has suggested that the most plausible explanation is found in the workplace or organizational environment (Schaufeli & Enzmann, 1998). Increasingly, research supports the notion that burnout arises out of a mismatch between the person and the job (Leiter & Laschinger, 2006; Maslach & Leiter, 1997).

Early conceptualization and research on burnout focused on the relationship between the care provider and care recipient as a necessary element in the development of burnout. In particular, the relationship was seen to contribute to emotional exhaustion which was thought to be the root cause of burnout. As research has shifted from descriptive to inferential study designs, findings have strongly suggested that this relationship was not the key driver contributing to burnout (Lee & Ashforth, 1996; Leiter, 1993). Research now supports six work-life issues involving person-job mismatch as the most likely explanation for burnout. These issues include: work overload, lack of control, lack of reward, lack of community, lack of fairness, and value conflict (Leiter & Laschinger, 2006; Leiter & Maslach, 2004; Maslach & Leiter, 1997).

Compassion Fatigue (Secondary Traumatic Stress)

The past twenty years have seen a rise in research linking exposure to pain, suffering, and trauma with the health of professionals providing care (Abendroth & Flannery, 2006; Adams, Boscarino, & Figley, 2006; Figley, 1999; Joinson, 1992; McCann & Pearlman, 1990; Pearlman, 1998; Pearlman & Saakvitne, 1995a; Sabo, 2010; Sabo, 2006). An offshoot of burnout, the term compassion fatigue first reflected the adverse psychosocial consequences experienced by emergency room nurses in a study exploring burnout (Joinson, 1992). Compassion fatigue has been described as the “natural consequent behaviours and emotions resulting from knowing about a traumatizing event experienced by a significant other – the stress resulting from helping, or wanting to help, a traumatized or suffering person” (Figley, 1995, p.7). Researchers have suggested that the phenomenon is connected to the therapeutic relationship between the healthcare provider and patient, in that the traumatic or suffering experience of the patient triggers a response, on multiple levels, in the provider. In particular, an individual’s capacity for empathy and ability to engage, or enter into, a therapeutic relationship is considered to be central to compassion fatigue. Theorists have argued that individuals who display high levels of empathy and empathic response to a patient’s pain, suffering, or traumatic experience are more vulnerable to experiencing compassion fatigue (Adams, et al., 2006; Figley, 2002b).

The dominant theoretical model postulating the emergence of compassion fatigue draws on a stress-process framework (Adams, et al., 2006; Figley, 2002a). Key elements within this model include empathic ability, empathic response, and residual compassion stress. The model is based on the assumption that empathy and emotional energy are the critical elements necessary for the formation of a therapeutic relationship and a therapeutic response. Although empathic ability has been defined as “the aptitude of the psychotherapist to notice the pain of others” (Figley, 2002a, p.1436), descriptions of these factors and of how each factor potentially interacts with another has been limited. The model is depicted as a series of cascading events beginning with exposure to a patient’s pain, suffering, and/or traumatic event. Empathic concern and empathic ability on the part of care providers, such as nurses, produce an empathic response which may result in compassion stress (residue of emotional energy). The risk increases if the nurse experiences (a) ongoing exposure to suffering, (b) memories that elicit an emotional response, or (c) unexpected disruptions in her/his life. Limitations of this model include an emphasis on a linear direction, along with the binary dimension of compassion fatigue, i.e., you either have it or you don’t. This binary dimension seems antithetical to human behavioral responses where individuals may express varying degrees of response. For example, an individual may not have compassion fatigue, yet may be slightly, moderately, or severely affected by a given interaction with a patient.

Figley (2002) also failed to clearly articulate the interaction(s) among the various influencing factors. The premise appears to be that if nurses care for patients who are suffering and/or traumatized, then they will inevitably experience compassion fatigue because of the use of empathy in their therapeutic or healing relationships. But not all authors view empathy in the same way. Some view empathy as the ability of an individual to enter into the world of others; to perceive other’s feelings/emotions and meaning associated with an experience (Walker & Alligood, 2001); and to correctly convey that understanding back to the individual, who in turn acknowledges and understands the other’s perceived understanding (La Monica, 1981). La Monica (1981) identified the nurse’s ability to pick up on an individual’s feelings/emotions as ‘helper perception,' ‘helper communication,' and ‘client perception’ (2001). Empathy has also been conceptualized as (a) a human trait, innate rather than taught; (b) a professional state (learned communication skill comprised of behavioral and cognitive elements); (c) caring (an understanding and need to act because of that understanding); and (d) a special relationship (reciprocity) (Kunyk & Olson, 2000). Figley’s (2002) model fails to clearly articulate the conceptualization of empathy on which his model is based, making it difficult to determine if one conceptualization may be antithetical to, or have more relevance than another in an understanding of compassion fatigue.

Another limitation of Figley’s (2002) model lies in its failure to address the ability ‘to get off the run-away train’ or to halt compassion fatigue’s progress. It also fails to adequately account for the benefits that nurses may derive from their relationships with patients or for how the therapeutic relationship may potentially serve to protect the nurse from experiencing compassion fatigue (Sabo, 2009, 2010). If the relationship is an empathic one, then it seems contradictory to suggest that empathy would lead to adverse effects. Rather, the contrary seems a more likely outcome; that is, when empathy is present the relationship would be more fulfilling.

...other factors may need to be explored beyond empathy. These factors may include resilience and hope... Given the lack of consideration regarding the benefits derived from the relationship, other factors may need to be explored beyond empathy. These factors may include resilience and hope, which may thwart the development of compassion fatigue allowing the nurse to experience positive effects from caring work. For example, hope may influence actions that individuals take, as well as foster and support relationships (Simpson, 2004). Building on this idea, a shared meaning of hope between nurse and patient may not only enhance the quality of the relationship but also satisfaction with the caring work. Resilience, defined as the capacity to move forward in a positive way from negative, traumatic, or stressful experiences (Walsh, 2006), has been shown to enhance relationships, facilitate emotional insight, and decrease vulnerability to adverse effects from the work environment (Jackson, Firtko, & Edenborough, 2007). Research into the role of personal characteristics, such as resilience and hope, as well as the nature of the relationship among families, patients, and nurses, and also the fit within Figley’s (2002) model of compassion fatigue, may help to add clarity and depth to a one-dimensional model.

In contrast to Figley’s (2002) explanatory model of compassion fatigue, Valent (2002) has hypothesized that compassion fatigue may emerge as the result of unsuccessful or maladaptive survival strategies. In particular, he attributed the development of compassion fatigue to the “unsuccessful, maladaptive psychological and social stress responses of Rescue-Caretaking. [The responses] are a sense of burden, depletion and self-concern; and resentment, neglect and rejection, respectively” (Valent, 2002, p.26) rather than as resulting from empathy. The description by Valent is somewhat reminiscent of an early label, ‘savior syndrome,’ used to describe the effect of the needs of nurses in providing care and also their affect responses (NiCathy, Merriam, & Coffman, 1984). Rather than nurses depicted as exemplary and selfless caregivers, they may be perceived as self-absorbed, using the therapeutic relationship for their own needs, instead of facilitating patients’ ability to fulfill their own needs. Taking this perspective into consideration, it would appear that a different concept may be at work in influencing compassion fatigue, a concept separate from empathy.

In one study that focused on the prevalence and risk for compassion fatigue among 216 hospice nurses, Abendroth and Flannery (2006) found that survey respondents in the moderate to high risk category for compassion fatigue (N=170) had ‘self-sacrificing behaviors’ as the major contributing factor for risk. Approximately 34% (N=47) of the 170 nurses who exhibited this behavior were in the high risk category for compassion fatigue. This group of nurses cared more for their patients than for themselves; their experiences increased life demands, post traumatic stress, and a lack of emotional support within the work environment. While the findings supported the notion that hospice care nursing was stressful, what remained unclear was the nature of the relationship among nurses, patients, and families and the role of relationships in either increasing or decreasing the risk for compassion fatigue. Additionally, individual characteristics (such as resilience) and organizational factors (such as management support, workload, values, and beliefs) were not considered. Research is needed to fully explore the role of self-sacrificing behavior as a contributing factor for increased risk of compassion fatigue, as well as the role of individual characteristics and organizational factors. To date, there have been few, if any studies exploring self-sacrificing behavior and the possible effects it may have on the psychosocial health of nurses. Further, there is a need to understand what effect self-sacrificing behavior may have on the ability of nurses’ skills, such as empathy and health-promoting personality traits, to self select high demand areas, such as oncology, critical care, or mental health.

Research is needed to fully explore the role of self-sacrificing behavior as a contributing factor for increased risk of compassion fatigue, as well as the role of individual characteristics and organizational factors. Exposure to traumatic stressors does not guarantee that an individual will manifest symptoms of compassion fatigue (Valent, 2002). Nor does targeting the negative aspects and/or symptoms provide answers to what, why, and how it is that some healthcare providers achieve satisfaction/rewards from the very same work that contributes to compassion fatigue in others (Abendroth & Flannery, 2006; Sabo, 2010). In light of this fact, more energy should be focused on exploring both the nature and roles of the relationship (nurse-patient-family) and empathy versus other related concepts, including the savior syndrome and engagement, in the psychosocial health and well being of nurses, and whether the risk changes for nurses working in different specialties.

To date, much of the research has been quantitative in nature. A variety of instruments exist to assess for the presence of secondary traumatic stress, including the Professional Quality of Life Scale-R-IV (Stamm, 2009), the Secondary Trauma Scale (Motta, Kefer, Hertz, & Hafeez, 1999), and the Secondary Traumatic Stress Scale (Bride, Robinson, Yegidis, & Figley, 2004).

While the use of instruments is helpful to highlight the incidence and prevalence of various types of occupational stress and to develop models highlighting influencing factors, it is also limiting. For example, nurses may respond to questions on one of several instruments used to indicate the presence or absence of occupational stress, yet the responses do little to explain how nurses perceive the nature of their work and what factors affect compassion fatigue or other types of occupational stress. The use of qualitative study designs may enhance an understanding of whether empathy and engagement have a role in the development of occupational stress or, perhaps more importantly, whether they serve as protective mechanisms against occupational stress by affording nurses the opportunity to share their stories and experiences in a way that goes beyond the objective and quantifiable (Sabo, 2010).

Vicarious Traumatization

Evidence within trauma research has supported the notion that psychological distress affects more than just those who have been personally traumatized (Collins & Long, 2003; Figley, 1999; Pearlman & Saakvitne, 1995a). The psychological distress experienced by healthcare professionals in their work with patients who are suffering or who have been traumatized has been labelled vicarious traumatization (Pearlman & MacIan, 1995). Defined as the “ [negative] transformation in the therapist’s (or other trauma worker’s) inner experience resulting from empathic engagement with clients’ trauma material” (Pearlmann & Saakvitne, 1995b, p.151), vicarious traumatization results in the permanent disruption of the individual’s cognitive schema. Researchers have suggested that ongoing exposure to graphic accounts of human cruelty, trauma, and suffering, as well as the healing work within the therapeutic relationship that is facilitated through ‘empathic openness’ (as is the case in compassion fatigue), may leave healthcare providers, including nurses, vulnerable to emotional and spiritual consequences (Dunkley & Whelan, 2006).

When a healthcare system places greater value on curative intent than on care, situations, such as futility of care, may occur. For nurses involved in providing such futile care, the lasting imprint may be vicarious traumatization. Additional factors beyond empathy have been identified as contributing to the development of vicarious traumatization. One factor considers the characteristics of healthcare professionals, including their previous personal history of abuse and/or personal life stressors, personal expectations, need to fulfill all patient needs, and inadequate training/inexperience. Another factor involves the characteristics of the treatment, such as invasiveness, life-threatening nature, and long-term effects, as well as its context, such as the type of patient and the political, social, and cultural context within which the treatment occurred and the traumatic event took place (Pearlman & MacIan, 1995; Pearlman & Saakvitne, 1995b). For example, ongoing advances in medical technology are now able to keep patients alive for longer periods of time, yet the eventual outcome is not altered. By this I mean that the patient still succumbs to the disease or injury; death has only been delayed. When a healthcare system places greater value on curative intent than on supportive care, situations, such as futility of care, may occur. For nurses involved in providing such futile care, the lasting imprint may be vicarious traumatization.

McCann and Pearlman (1990), and later Pearlman and Saakvitne (1995), used constructivist self-development theory (CSDT) to explain the “progressive development of a sense of self and world view in response to life experiences” (Pearlman & Saakvitne, 1995b, p.151). In other words, one’s unique history of life experiences shapes how one will experience, interpret, and adapt to traumatic or highly stressful events. This CSDT interactive model attempts to take into account the variability of life experiences, suggesting that vicarious traumatization is unique to the individual (McCann & Pearlman, 1990; Pearlman & Saakvitne, 1995b). For example, if the nurse grew up in a home environment where one coped by dealing with stressful situations through escape/avoidance behaviour (a negative coping strategy), one would likely employ the same coping strategy in other stressful situations, such as that of witnessing ongoing patient suffering. If negative coping strategies are coupled with other contributing factors, for example lack of emotional support and/or unrealistic expectations of self in one’s role as care provider, the risk for vicarious traumatization may be increased (Saakvitne, Tennen, & Affleck, 1998).

This theory argues that exposure to trauma, whether direct or indirect, disrupts one’s frame of reference in one of five core areas of need, namely safety, trust, esteem, control, and intimacy (McCann & Pearlman, 1990). For example, disruption may occur whether the nurse witnesses the devastation of war first hand while serving in a MASH unit in Afghanistan or whether the nurse listens to her/his patient’s eyewitness accounts of the devastation of war while providing care in a healthcare facility. As a result of either exposure the nurse may experience the following: (a) difficulty establishing and maintaining relationships with others; (b) loss of independence; (c) inability to tolerate extreme emotional responses to stressful situations; (d) intrusive memories of the traumatic experience (similar to post traumatic stress); and/or (e) an altered belief system.

Memory plays an important role in the development of vicarious traumatization by serving as a mental recording of life experiences and its interpretations. CSDT emphasizes the importance of the individual’s ability to connect with others, perceive the self as competent, cope effectively with stress over time, and interpret experiences in a meaningful way that allows the individual to draw on previous experience to manage new experiences successfully (McCann & Pearlman, 1990; Pearlman & Saakvitne, 1995b). Memory plays an important role in the development of vicarious traumatization by serving as a mental recording of life experiences and its interpretations. For example, healthcare providers may assimilate/integrate the patient’s experiences of trauma and suffering as their own which, in turn, reshapes the provider’s beliefs and values of self and of the world (McCann & Pearlman, 1990).

Although there is increasing evidence to support CSDT as an explanatory model for vicarious traumatization, more research is needed to demonstrate how, and in what way, the therapeutic relationship, individual core beliefs, and exposure to pain, suffering, and trauma may affect the psychosocial health and well being of healthcare professionals working in high-demand, intense, complex environments. Limitations of this theory include an inability to recognize the positive effects of trauma work and distinguish between awareness and disturbances in cognitive schemas (Dunkley & Whelan, 2006). For example, a disturbance in cognitive schema (beliefs) may occur when a hematological cancer nurse finds her/himself believing that all patients with hematological cancer die. Alternatively, heightened awareness occurs when an experienced hematological cancer nurse recognizes certain cues triggering the belief that a particular patient will do poorly but not that all patients will do poorly. Changes in cognitive schema may interfere with the development of empathy leading to vicarious traumatization rather than empathy leading to vicarious traumatization.

...not every individual who works with those who have been traumatized will develop vicarious traumatization. It should be noted that not every individual who works with those who have been traumatized will develop vicarious traumatization. If, as researchers have suggested, empathy and engagement, as fundamental elements of the therapeutic relationship, are key factors in increasing the risk for vicarious traumatization, then one would expect to see large numbers of healthcare providers negatively affected as a result of their work. However, studies have suggested that only a small percentage of individuals will manifest symptoms consistent with vicarious traumatization (Hafkenscheid, 2005), far fewer individuals than what McCann and Pearlmann (1990) had hypothesized. What is still missing is a clearly articulated theoretical framework and evidence demonstrating a cause-effect relationship between adverse effects and empathy. Future research is needed to identify which characteristics or qualities of working with suffering/traumatized patients might protect the healthcare professional and/or decrease the risk for adverse effects such as vicarious traumatisation.

Relationship Between Compassion Fatigue and a Continuum of Occupational Stress

What becomes apparent in reviewing the literature on possible adverse effects of providing care is the level of complexity underlying the various types of occupational stress. This may be due, in part, to the relatively preliminary understanding of compassion fatigue and vicarious traumatisation, concepts that began to emerge only in the early 1990’s. To date, a lack of empirical evidence exists to support a theoretical framework for these two types of occupational stress (Bride, et al., 2004; Jenkins & Baird, 2002; Sabin-Farrell & Turpin, 2003; Thomas & Wilson, 2004). In contrast, research exploring burnout has consistently supported the existence of a multi-dimensional model comprised of three critical elements: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment (Demerouti, Bakker, Vardakou, & Kantas, 2003; Kalliath, O'Driscoll, Gillespie, & Bluedorn, 2000; Kitaoka-Higashiguchi, et al., 2004; Langballe, Falkum, Innstrand, & Aasland, 2006; Maslach, et al., 2001; Roelofs, Verbraak, Keijsers, de bruin, & Schmidt, 2005). These elements, however, are no longer considered to be specific to provider-recipient interactions. Rather, burnout can occur in the absence of such interactions. Hence it would not appear unreasonable to suggest that burnout may be a pre-condition for the other types of occupational stress, namely compassion fatigue and vicarious traumatisation, by creating the fertile ground for these types of stress to develop.

...compassion fatigue is amenable to treatment intervention and individuals may continue to work successfully in their chosen field. While all three types of occupational stress share aspects of the therapeutic relationship (empathy and engagement) as influencing factors, researchers exploring factors associated with the onset of burnout have shifted their emphasis to work-life issues, such as lack of resources, leadership, and shared values (Leiter & Laschinger, 2006). Research has yet to provide clarity and understanding as to whether empathy and engagement have a role in contributing to, or protecting the nurse from compassion fatigue and vicarious traumatisation. Further research may be helpful in explaining whether and how factors, such as (a) duration of the relationship; (b) level of experience; and (c) individual characteristics of the nurse (e.g., ‘savior syndrome’); as well as (d) patient characteristics, increase risk for compassion fatigue and vicarious traumatization.

Factors within the work environment, such as work load and limited resources, have all been identified as influencing the potential risk of developing occupational stress. Differences appear to lie in the nature of the work. Individuals experiencing compassion fatigue and vicarious traumatization appear to work with high demand populations, such as paediatric oncology (Maytum, et al., 2004; Papadatou, Martinson, & Chung, 2001), critical care (Mobley, Rady, Verheiide, Patel, & Larson, 2007), mental health (Collins & Long, 2003) or those experiencing pain/suffering or trauma (Figley, 1995; Pearlman & MacIan, 1995). In contrast, research on burnout has extended beyond the healthcare environment to include all work environments regardless of whether people-work is fundamental to the job (Maslach & Leiter, 1997) suggesting that the relationship is not central to the development of occupational stress. At this point in time, it is unclear whether or not burnout is a precondition for compassion fatigue. It is also worth noting that a clear distinction between compassion fatigue and vicarious traumatization lies in the permanency of change to the individual. Individuals experiencing vicarious traumatization have their cognitive schema permanently altered. In contrast, compassion fatigue is amenable to treatment intervention and individuals may continue to work successfully in their chosen field. With this in mind, it would seem plausible to suggest that compassion fatigue precedes vicarious traumatization if one chooses to envision a stress continuum.

Relationships Between Types of Occupational Stress

As of this writing there is no research to support a claim that any or all of these types of occupational stress are concept redundant or interrelated. Sufficient evidence exists to demonstrate the validity of each as a distinct concept. What is not known is the role each may play in the development of the other. In reflecting on the current theoretical conceptualizations for burnout, compassion fatigue, and vicarious traumatization, one can raise the following questions:

- Does compassion fatigue exist on a continuum of occupational stress? If so, is burnout a pre-condition for compassion fatigue?

- What are the relationships between the types of occupational stress? To what extent does non-resolution of compassion fatigue increase the risk for developing vicarious traumatization?

Let’s consider the above questions within the context of the following scenarios.

Scenario One

You have been working on a medical/surgical unit for three years. Since you started working on this floor the unit has experienced numerous changes as a result of fiscal restructuring. The dedicated Clinical Nurse Educator and Charge Nurse positions have been eliminated and all nurses on the floor rotate through the latter position for six-month periods of time. Further, you no longer have a nurse as manager for your unit. Instead, several units have been consolidated under one manager who has had no prior experience in the acute care setting and who does not hold a professional degree in a health-related discipline. Rather, the manager holds a Master’s in Business Administration degree. Over the past 10 months the nurses have had their workload doubled, found themselves working more overtime shifts, and seen the complexity of patients increase. Nurses rarely hear they have done a good job. Nor do they have appreciable input in the ongoing changes. They are feeling increasingly disenfranchised and stressed. Sick time has increased, more nurses are leaving, and the unit has had difficulty recruiting new nurses to the unit because of increasing interpersonal conflicts. The most likely outcome in this scenario is burnout if the situation is not resolved. Emphasis here would appear to be an apparent disconnect between job demand and available resources.

Scenario Two

Scenario one is allowed to continue without remediation. Over the next year the complexity of patients increases and favourable prognoses decline. There have been several difficult deaths in recent weeks, particularly among younger patients. With little time to connect with families in crisis because of time and resource issues, the nurses are finding it increasingly difficult to continue working on the unit. The level of emotional distress has increased. Nurses who had been friendly and outgoing are now more reserved and withdrawn. Some nurses have identified feeling guilty over poor patient outcomes while others have begun to perceive that all patients with a specific diagnosis will die. Management perceives the problem to be related to burnout. Strategies to address the problem have proven unsuccessful. Is this a situation of burnout or compassion fatigue? At what point does occupational stress stop being burnout and become compassion fatigue?

In this scenario, the nurses would appear to be experiencing compassion fatigue. In burnout, emotional exhaustion is considered a cornerstone element along with cynicism and decreased personal accomplishment. In contrast, nurses experiencing compassion fatigue exhibit an intensified level of emotional distress leading to interpersonal withdrawal and changes in their beliefs, expectations, and assumptions. Furthermore, the nurses experience ‘witness guilt,’ taking personal blame for their inability to resolve a situation, such as easing the pain and suffering of a patient. Although some signs and symptoms may overlap across all three types of occupational stress (See Table), the level of intensity as well as additional symptoms can be helpful in differentiating between types of occupational stress. It may well be that initially the lines are blurred between burnout and compassion fatigue because of overlap in the signs of both burnout and compassion fatigue. Yet as the situation continues to deteriorate, more signs of compassion fatigue may appear.

As a reader you may have recognized that some signs or characteristic of depression are present in compassion fatigue. In a recently completed study conducted by myself and colleagues (unpublished as of this writing) the researchers did observe a statistically significant correlation between the presence of clinical depression and compassion fatigue among caregivers of hematological stem cell transplant recipients. Hence there is evidence for some overlap between compassion fatigue and depression.

Scenario Three

A nurse working on the unit described in scenarios one and two makes the decision to change practice areas and shifts to working in a community health clinic in the belief that a change of work environment will support the return of physical, psychological, and emotional well being. The community health clinic provides health services for a local shelter for abused women and children. Initially the nurse notes an improvement in overall health and well being; however, this improvement is not sustained. During the course of working with clients accessing the clinic, the nurse hears ongoing stories of abuse. Over a period of time the nurse begins to experience intrusive images of clients’ stories of abuse. As time continues, the nurse’s relationship with her spouse deteriorates. A once loving, intimate relationship no longer exists. Touch, in particular evokes hostility. On occasion, the nurse has noted feelings of panic when in the presence of unknown males (e.g., while waiting for the bus). Further, the nurse’s sense of trust in the compassion and caring of others has changed. Trust is no longer present. What is happening here? Is this vicarious traumatization? Can this occur without the presence of burnout or compassion fatigue?

In this situation, it is likely the nurse is experiencing symptoms associated with vicarious traumatization. The symptoms of intrusive imagery; changes in values, beliefs, and assumptions (cognitive shift); anxiety; and loss of trust form hallmark signs of vicarious traumatization. While it is possible that each form of stress may create the stage for the next to occur, behaviour and experience is not linear. Nor is the continuum on which burnout, compassion fatigue, and vicarious traumatization may exist. Rather, individuals may move back and forth, at times experiencing symptoms of all three. We do not currently have evidence to support a continuum of occupational stress ranging from burnout to compassion fatigue to vicarious traumatization. Nor can we say that one person, at a given time, can be described as being at only one point on the continuum. The nurse in scenario three could have come from a healthy work environment and yet still experience vicarious traumatization. It is also reasonable to assume that burnout can exist concurrently with either compassion fatigue or vicarious traumatization. What and how each form of occupational stress influences the other requires further research.

Conclusion

Research clearly demonstrates that working with patients who are in pain, suffering, or at end of life may take a toll on the psychosocial health and well being of nurses. Research clearly demonstrates that working with patients who are in pain, suffering, or at end of life may take a toll on the psychosocial health and well being of nurses. Over the past ten years compassion fatigue has received considerable attention as a potential form of occupational stress experienced by nurses. At the same time, the lack of theoretical clarity underlying compassion fatigue has led to a number of questions ranging from the role of empathy and empathic response in the development of compassion fatigue to the possibility of a continuum of stress. More research is needed to articulate clearly not only what factors may mitigate and/or mediate the onset of compassion fatigue but also to clarify its theoretical underpinnings if we hope to develop and implement sustainable interventions to support positive psychosocial health and well being among all nurses caring for patients who are in pain, suffering, or at the end of life.

Table - Overview of Burnout, Compassion Fatigue and Vicarious Traumatization (see pdf version)

Author

Brenda Sabo, PhD, RN

E-mail: Brenda.Sabo@dal.ca

Dr Sabo is a Professor in the School of Nursing at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. She teaches family and oncology nursing. Additionally, Dr Sabo maintains a clinical practice with the Nova Scotia Cancer Center where she provides psychotherapy, counselling, and emotional support for patients, families, and couples living with, and affected by cancer. This counselling spans the disease continuum, from the point of diagnosis to the end of life. Dr Sabo’s research focuses on both occupational stress among healthcare professionals who work with oncology patients and on family and dyadic adjustment, coping style, and psychological distress in couples within this population. More recently, Dr Sabo has begun to explore the meaning of hope among healthcare professionals, patients, and families within the context of cancer. She has published in the areas of occupational stress, compassion fatigue, and finding cancer meaning through art. Dr. Sabo received her nursing diploma from the Winnipeg (Manitoba, Canada) Health Science Center School of Nursing, her BA from the University of Manitoba, and her MA (Anthropology) and PhD (Nursing) degrees from Dalhousie University.

© 2011 OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing

Article published January 31, 2011

References

Abendroth, M., & Flannery, J. (2006). Predicting the risk of compassion fatigue: A study of hospice nurses. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing, 8(6), 346-356.

Adams, R., Boscarino, J., & Figley, C. (2006). Compassion fatigue and psychological distress among social workers: A validation study. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 76(1), 103-108.

Bakker, A., Le Blanc, P., & Schaufeli, W. (2005). Burnout contagion among intensive care nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 51(3), 276-287.

Bakker, D., Fitch, M., Green, E., Butler, L., & Olsen, K. (2006). Oncology nursing: Finding the balance in a changing health care system. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal, 16(2), 79-98.

Blomberg, K., & Sahlberg-Blom, E. (2007). Closeness and distance: A way of handling difficult situations in daily care. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 16, 244-254.

Bride, B. E., Robinson, M. M., Yegidis, B., & Figley, C. (2004). Development and validation of the secondary traumatic stress scale. Research on Social Work Practice, 14(1), 27-35.

Collins, S., & Long, A. (2003). Too tired to care? The psychological effects of working with trauma. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 10, 17-27.

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A., Vardakou, I., & Kantas, A. (2003). The convergent validtiy of two burnout instruments: A multitrait-multimethod analysis European Journal of Psychological Assessment 19(1), 12-23.

Dunkley, J., & Whelan, T. (2006). Vicarious traumatization: Current status and future directions. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 34(1), 107-116.

Edwards, D., & Burnard, P. (2003). A systematic review of stress and stress management interventions for mental health nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 42(2), 169-200.

Ekedahl, M., & Wengstrom, Y. (2007). Nurses in cancer care-stress when encountering existential issues. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 11, 228-237.

Figley, C. (1995). Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized. New York, NY: Brunner-Routledge.

Figley, C. (1999). Compassion fatigue: Toward a new understanding of the costs of caring. In B. H. Stamm (Ed.), Secondary traumatic stress: Self care issues for clinicians, researchers and educators (2 ed., pp. 3-28). Lutherville: Sidran.

Figley, C. (2002a). Compassion fatigue: Psychotherapists' chronic lack of self care. Psychotherapy in Practice, 58(11), 1433-1441.

Figley, C. (2002b). Treating compassion fatigue. New York, NY: Brunner-Routledge.

Goldberg, L. (1990). An alternative "Description of personality": The Big-Five factor structure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 1216-1229.

Hafkenscheid, A. (2005). Event countertransference and vicarious traumatization: Theoretically valid and clinically useful concepts? European Journal of Psychotherapy, Counselling and Health, 7(3), 159-168.

Hertting, A. (2003). The healthcare sector: A challenging or draining work environment. Psychosocial work experiences and health among hospital employees during the Swedish 1990's. PhD, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm.

Hertting, A., Nilsson, K., Theorell, T., & Larsson, U. (2004). Downsizing and reorganization: demands, challenges and ambiguity for registered nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 45(2), 145-154.

Jackson, D., Firtko, A., & Edenborough, M. (2007). Personal resilience as a strategy for surviving and thriving in the face of workplace adversity: A literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 60(1), 1-9.

Jenkins, R., & Elliott, P. (2004). Stressors, burnout and social support: Nurses in acute mental health settings. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 48(6), 622-631.

Jenkins, S. R., & Baird, S. (2002). Secondary traumatic stress and vicarious traumatization: a validational study. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 15(5), 423-432.

Joinson, C. (1992). Coping with compassion fatigue. Nursing 22(4), 116-122.

Kalliath, T., O'Driscoll, M., Gillespie, D., & Bluedorn, A. (2000). A test of the Maslach Burnout Inventory in three samples of healthcare professionals. Work & Stress, 14(1), 35-50.

Kitaoka-Higashiguchi, K., Nakagawa, H., Ishizaki, M., Miura, K., Naruse, Y., Kido, T., et al. (2004). Construct validtiy of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey. Stress & Health, 20, 255-260.

Kunyk, D., & Olson, J. (2000). Clarification of conceptualizations of empathy. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 35(3), 317-325.

La Monica, E. (1981). Construct validity of an empathy instrument. Research in Nursing and Health, 4, 389-400.

Langballe, E., Falkum, E., Innstrand, S., & Aasland, O. (2006). The factorial validity of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey in representative samples of eight different occupational groups. Journal of Career Assessment, 14(3), 370-384.

Laschinger, H., & Finegan, J. (2005). Empowering nurses for work engagement and health in hospital settings. JONA, 35(10), 439-449.

Lee, R. T., & Ashforth, B. E. (1996). A meta-analytic examination of the correlates of the three dimensions of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(2), 123-133.

Leiter, M. (1993). Burnout as a developmental process: consideration of models. In W. Schaufeli, C. Maslach & T. Marek (Eds.), Professional Burnout: Recent developments in theory and research (pp. 237-250). London: Taylor & Francis.

Leiter, M. (2005). Perception of risk: An organizational model of occupational risk, burnout, and physical symptoms. Anxiety, Stress and Coping, 18(2), 131-144.

Leiter, M., & Laschinger, H. (2006). Relationships of work and practice environment to professional burnout: testing a causal model. Nursing Research, 55(2), 137-146.

Leiter, M., & Maslach, C. (2004). Areas of worklife: A structural approach to organizational predictors of job burnout. In P. Perrewe & D. Ganster (Eds.), Research in occupational stress and well being: Vol 3. Emotional and physiological processes and positive intervention strategies (pp. 91-134). Oxford: JAI Press/Elsevier.

Leiters, M., & Schaufeli, W. (1996). Consistency of the burnout construct across occupations. Anxiety, Stress and Coping, 9, 229-243.

Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. (1986). Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual (2 ed.). Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. (1997). The Truth About Burnout: How organizations cause personal stress and what to do about it. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Boss.

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W., & Leiter, M. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Reviews in Psychology, 52, 397-422.

Maytum, J., Bielski-Heiman, M., & Garwick, A. (2004). Compassion fatigue and burnout in nurses who work with children with chronic conditions and their families. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 18, 171-179.

McCann, L., & Pearlman, L. (1990). Vicarious traumatization: A framework for understanding the psychological effects of working with victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 3(1), 131-149.

Mobley, M., Rady, M., Verheiide, J., Patel, B., & Larson, J. (2007). The relationship between moral distress and perceptions of futile care in a critical care unit Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 23, 256-263.

Motta, R. W., Kefer, J. M., Hertz, M. D., & Hafeez, S. (1999). Initial evaluation of the Secondary Trauma Questionnaire. Psychological Reports, 85, 997-1002.

NiCathy, G., Merriam, K., & Coffman, S. (1984). Talking it out: A guide to groups for abused women. Seattle: Seal Press.

Papadatou, D., Martinson, I., & Chung, P. (2001). Caring for dying children: A comparative study of nurses' experience in Greece and Hong Kong. Cancer Nursing, 24(5), 402-412.

Pearlman, L. (1998). Trauma and the self: A theoretical and clinical perspective. Journal of Emotional Abuse, 1, 7-25.

Pearlman, L., & MacIan, P. (1995). Vicarious traumatization: An empirical study of the effects of trauma work on trauma therapists. Professional Psychology, Research and Practice, 26(6), 558-565.

Pearlman, L., & Saakvitne, K. (1995a). Trauma and the Therapist: Countertransference and vicarious traumatization in psychotherapy with incest survivors. London: W.W. Norton.

Pearlman, L., & Saakvitne, K. (1995b). Treating therapists with vicarious traumatization and secondary traumatic stress disorders. In C. R. Figley (Ed.), Compassion Fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized. New York: Brunner-Routledge.

Roelofs, J., Verbraak, M., Keijsers, G., de bruin, M., & Schmidt, A. (2005). Psychometric properties of a Dutch version of hte Maslach Burnout Inventory General survey (MBI-DV) in individuals with and without clinical burnout. Stress & Health, 21, 17-25.

Saakvitne, K., Tennen, H., & Affleck, G. (1998). Exploring thriving in the context of clinical trauma theory: constructivit self development theory. Journal of Social Issues, 54(2), 279-299.

Sabin-Farrell, R., & Turpin, G. (2003). Vicarious traumatization: Implications for the mental health of health workers? clinical Psychology Review, 23, 449-480.

Sabo, B. (2009). Nursing from the heart: An exploration of caring work among hematology/blood and marrow transplant nurses in three Canadian tertiary care centres PhD, Dalhousie University, Halifax.

Sabo, B. (2010). Compassionate presence: The meaning of hematopoietic stem cell transplant nursing. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2010.06.006.

Sabo, B. M. (2006). Compassion fatigue and nursing work: Can we accurately capture the consequences of caring work? International Journal of Nursing Practice, 12, 136-142.

Schaufeli, W., & Enzmann, D. (1998). The Burnout Companion to Study and Practice: A critical analysis. London: Taylor & Francis.

Simpson, C. (2004). When hope makes us vulnerable: A discussion of patient-healthcare provider interactions in the context of hope. Bioethics, 18(5), 428-447.

Stamm, B. (2009). The concise manual for the Professional Quaity of LIfe Scale: The ProQOL. Pocatello, ID: ProQOL.org.

Thomas, R., & Wilson, J. (2004). Issues and controversies in the understanding and diagnosis of compassion fatigue, vicarious traumatization and secondary traumatic stress disorder. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health, 6(2), 81-92.

Valent, P. (2002). Diagnosis and treatment of helper stresses, traumas, and illnesses. In C. Figley (Ed.), Treating Compassion Fatigue (pp. 17-37). New York: Brunner - Routledge.

Walker, K., & Alligood, M. (2001). Empathy from a nursing perspective: Moving beyond borrowed theory. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 15(3), 140-147.

Walsh, F. (2006). Strengthening Family Resilience. New York: Guilford Press.