Electronic patient education and communications, such as email, text messaging, and social media, are on the rise in healthcare today. This article explores potential uses of technology to seek solutions in healthcare for such challenges as modifying behaviors related to chronic conditions, improving efficiency, and decreasing costs. A brief discussion highlights the role of technologies in healthcare informatics and considers two theoretical bases for technology implementation. Discussion focuses more extensively on the ability and advantages of electronic communication technology, such as e-mail, social media, text messaging, and electronic health records, to enhance patient-provider e-communications in nursing today. Effectiveness of e-communication in healthcare is explored, including recent and emerging applications designed to improve patient–provider connections and review of current evidence supporting positive outcomes. The conclusion addresses the vision of nurses’ place in the vanguard of these developments.

Key words: healthcare, electronic communication, email, text messaging, social media, social networks, Facebook®, Twitter®, EHR, nursing informatics, patient education, patient-provider communication, positive health outcomes, patient-centered care, compliance, healthcare cost-savings, disruptive innovation, diffusive innovation

...many clinicians have not yet had opportunity to put electronic outreach to work in delivering patient-centered care. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (also known as the “Stimulus Package”) provided incentives, such as extra Medicare and Medicaid payments and direct federal loans and grants for hospitals to adopt health information technology (Department of Health and Human Services, 2012) . Despite these incentives, as well as research supporting the efficacy of electronic communication with patients, many clinicians have not yet had opportunity to put electronic outreach to work in delivering patient-centered care. Nurses, however, are uniquely positioned to change that by using e-communication technology to create and sustain patient-provider connections that improve outcomes.

The time has come for nurses to seize this opportunity. With the emerging push to have more services and care provided outside of hospitals and to manage populations of patients—both part of the movement toward the Patient-Centered Medical Home—nurses are likely to be enlisted as the connectors to this new out-of-hospital care model. Nurses will be tasked with managing patient connections while supporting quality and efficiency. Electronic communication technology will be a critical factor in enabling nurses to accomplish this goal.

There’s no doubt that we live in an increasingly electronic world, but the latest numbers from the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project make it clear:

- 85% of Americans are online (Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project, 2012b, para. 1).

- 55% of US adults go online wirelessly (Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project, 2012c, para. 1).

- Small screens outnumber big screens: Almost half of US adults own a smartphone (Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project, 2012a, para. 1).

- 17% of US adult cell phone owners use their phones to look up health or medical information (Purcell, 2012, Slide 22).

To a greater extent than ever before, communicating electronically and on the go is how people connect. Statistics from the past year tell us that we are rapidly moving toward mobile devices. For example, the percentage of U.S. adults who own a smartphone increased 11% between May 2011 and February 2012 (Pew Internet and American Life Project, 2012a). To a greater extent than ever before, communicating electronically and on the go is how people connect.

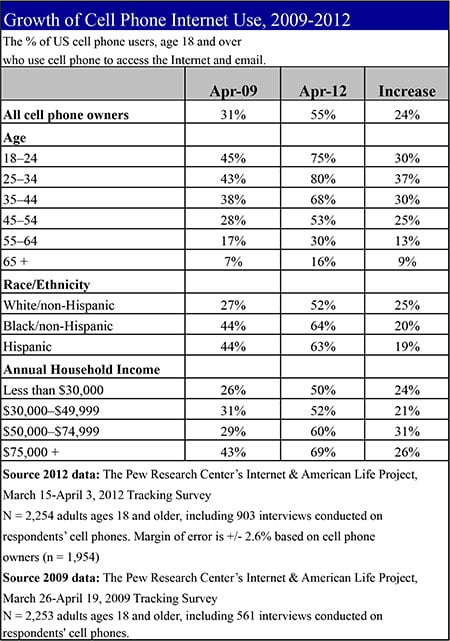

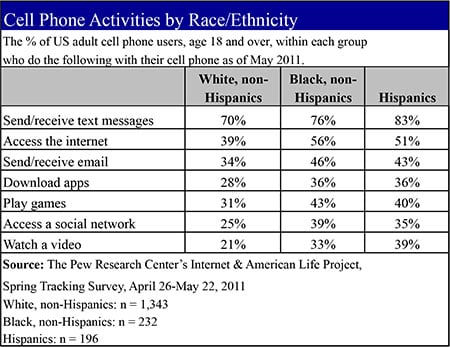

Methods of communication are also changing. It was not that long ago that email was the sole form of electronic communication. While it is still the dominant method—91% of U.S. adults use email—shorter messaging is on the rise. In the US, 67% of adult cell phone owners use text messaging (also known as SMS, or short message system). Social networking (e.g., Facebook®, Google Plus®) is also garnering more attention, with 50% of U.S. adults using some type of social site. Furthermore, minority Internet users are significantly more likely than non-Hispanic whites to use social sites; watch videos; send or receive phone text messages; and send or receive email on their cell phones (Pew Internet & American Life Project, 2011). Tables 1 through 3 provide additional information about use of electronic communication.

|

|

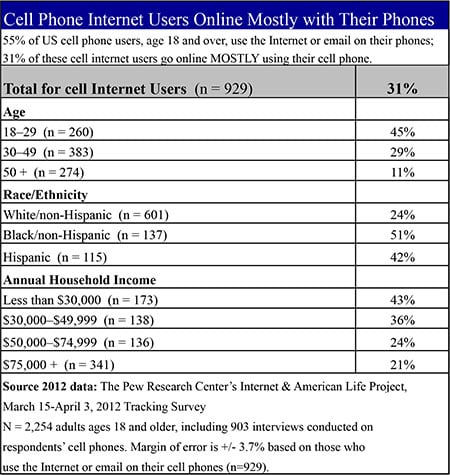

|

Table 3: Cell Phone Internet Users Online Mostly with Their Phone |

|

What does this mean to healthcare, and more strategically, to nurses? To understand this requires first examining the current challenges facing healthcare. This article explores potential uses of technology to seek solutions in healthcare for such challenges; briefly highlights the role of technologies in healthcare informatics; and considers two theoretical bases for technology implementation. Discussion focuses more extensively on the ability and advantages of electronic communication technology to enhance patient-provider e-communications and explores the effectiveness of e-communication in healthcare. The conclusion addresses the vision of nurses’ place in the vanguard of these developments.

Seeking Solutions in Healthcare

Problems in healthcare today are well known and unsustainable, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Health expenditures in the US are 16% of the gross domestic product, and that number is on an upward trajectory (CDC, 2011).

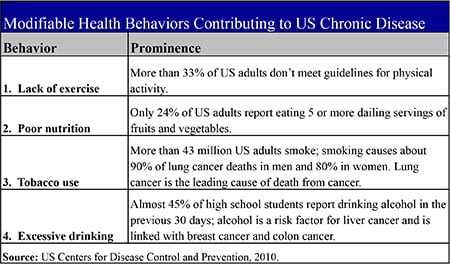

At the same time, serious chronic diseases and conditions, such as heart disease, cancer, diabetes, arthritis, and obesity, are common, costly, and on the rise. Though preventable, chronic conditions account for 70% of U.S. deaths. The CDC (2010) cites four specific, changeable behaviors as the central causes of these chronic ailments: lack of exercise, poor nutrition, tobacco use, excessive alcohol consumption (see Table 4). We also know that people who take prescription medications typically take less than half the prescribed doses, just one of a multitude of deficiencies surrounding patients and prescription medications (Haynes, Ackloo, Sahota, McDonald, & Yao, 2008).

|

Table 4: Modifiable Health Behaviors that Contribute to U.S. Chronic Diseases |

|

While there is no simple solution to these problems, electronic communication technology must be part of the overall approach. Whether used to educate, remind, and engage patients or to monitor their behavior and provide feedback, electronic communications can save time, effort, and thus dollars, as well as improve outcomes by enabling patients to become more competent partners in their care.

Patient-Provider E-Communications in Nursing Today

Role of Technology in Healthcare Informatics

Use of technology to connect providers and patients is one aspect of healthcare informatics. Use of technology to connect providers and patients is one aspect of healthcare informatics. For nurses, informatics is a growing field that “integrates nursing science, computer science, and information science to manage and communicate data, information, knowledge and wisdom in nursing practice” (Anderson, C. et al., 2012, slide 4). According to the 2007 Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society (HIMSS) Nursing Informatics Survey, almost one-fifth of survey responders had a master’s or doctorate degree, an increase of 11% since 2004. On-the-job training may be lagging, though, as about half as many respondents said they were learning on the job as compared to the same survey three years earlier (HIMSS, 2007). There remains a gap between what is happening in nursing academia and in the trenches of patient care. However, this small, growing group of technically trained nurses is positioned to emerge as leaders in today’s evolving healthcare system, prepared to take advantage of information technologies in terms of patient care and support.

When it comes to technology and nursing, “there are a variety of mechanisms in play right now,” notes Marisa Wilson, DNSc, MHSc, RN-BC, assistant professor and nursing informatics expert at the University of Maryland School of Nursing (M. Wilson, personal communication, April 24, 2012). When it comes to provider-patient communications, the most basic way that nurses can be involved is through what Wilson refers to as “the web front door” represented by hospital websites. While many of these entryways are used primarily for public relations, Wilson wonders why nurses are not doing more to harness this opportunity to strengthen communication with patients. “Usually, there’s untapped functionality there,” she says. “Why are we not seeing attachments (e.g., resources or tools) or entries to invited Facebook sites, where nurses could manage chronically ill populations of patients through social networking?”

One reason, Wilson says, is “nurses get so bogged down in redoing workflows, redesigning systems, refiguring out what to do at the point of care with these systems that the thought of dealing with social media or email to manage patients is not even on their radar.” Nevertheless, she notes that there is opportunity for nurses to use today’s e-communication tools to foster “patient activation” in their own care—engaging them to be better partners with care providers and more effectively manage their health, particularly when it comes to chronic illness (M. Wilson, personal communication, April 24, 2012).

By communicating with patients via email, invited Facebook® groups, text messages, websites and more, [nurses] will help define how each of these channels is used to enhance patient connection and support. While direct electronic connections with patients around a specific condition, treatment, or procedure are not yet the norm at many institutions, healthcare is now on the cusp of a new approach to communication in patient care. The tools are evolving quickly and nurses will have a role to play.

Nurses can be the prime connectors between patients and healthcare institutions. By communicating with patients via email, invited Facebook® groups, text messages, websites and more, they will help define how each of these channels is used to enhance patient connection and support. To do this, though—especially in a way that saves nursing time, rather than simply adds another task—nurses must become fluent in these technologies, understanding the efficacy of each, and being ready to adopt new ones as they come along. Fortunately, this vision of the future is neither distant nor unattainable because it arises from a foundation of success already established in today’s primary e-communication channels. Consider, for example, the cornerstones of email, social media, and text messaging.

Theoretical Bases for Technology Implementation

In our experience at UbiCare working with over 250 hospitals worldwide, we have seen firsthand the adoption of these tools, most often by nurses. While about one-third of these hospitals have not previously used electronic tools and find them daunting, another third are making progress in their adoption of these tools. The final third, however, are really using them and finding them increasingly valuable.

Focusing on this latter group of early adopters, we have observed changes in staff efficiency, patient care, compliance, and sense of connection to the hospital (Deloitte, 2011). The theoretical underpinnings of these changes can be related to Everett Rogers’s diffusion of innovation theory (Orr, 2003) and Clayton Christensen’s (1997) disruptive innovation theory. While Rogers’s theory (Rogers, 2003) may explain what is going on as nurses adopt and capitalize on electronic communication tools and opportunities in their work, Christensen’s theory is even more central to what is happening. ... this technology in the hands of nurses is disrupting the status quo in patient education and communication. Why? Because the disruptive innovation of electronic communications technology is flipping healthcare on its head, especially in light of the coming shift to care outside of the hospital—much of which will, of necessity, be facilitated by and dependent on technology, especially electronic communications technology.

But, who is controlling this technology? Our observation is that those nurses who “get it,” or realize the importance and potential of electronic communication, are changing their organizations, and doing so in less time, with less effort, and while spending less money. They have done so with electronic tools that they can control and customize. So this technology in the hands of nurses is disrupting the status quo in patient education and communication. At the same time, it has created a new marketplace for technology services like those provided by UbiCare and others.

...providers (especially nurses) can not only directly share the most reliable and relevant information and resources with patients, they can also steer them away from ones likely to cause heightened anxiety or worse outcomes. Over time, these new models of electronic communication will replace the old. This will be expedited as nurses and healthcare providers seize the opportunity and eventually begin to mold their use of technology to their own needs, as well as those of their patients. Patients, otherwise left to their own devices to navigate an increasingly abundant, yet murky, world of health information on the internet, are becoming more dependent on finding trusted guides (e.g., nurses). Healthcare providers are conversely spending increasing amounts of time correcting patients’ self-diagnoses. In fact, some care providers have come to view with disdain the Internet-enabled “Google stacks”—printouts from unreliable health-related websites—that some patients haul in to appointments. By making effective use of available electronic communication technologies, providers (especially nurses) can not only directly share the most reliable and relevant information and resources with patients, they can also steer them away from ones likely to cause heightened anxiety or worse outcomes.

The following section will discuss the ability and advantages of electronic communication technology, such as e-mail, social media, text messaging, and electronic health records, to enhance patient-provider e-communications in nursing today.

Email is the e-communication technology most pervasive in healthcare. Email. Email is the e-communication technology most pervasive in healthcare. In 2009, the most recent statistics available, the National Center for Health Statistics found that about 5% of adults ages 18 to 64 had communicated with a healthcare provider by email in the previous 12 months (Cohen & Strussman, 2010). Given the increasing adoption of electronic communications in all forms, it seems safe to assume that this number has grown in the past three years. It also represents an area ripe for further use.

One-to-one electronic communication between nurses and patients may be in its infancy (or perhaps toddlerhood), but the advantages are many, and the expectation among patients is that they will increasingly use these types of electronic connections. Patients have shown great interest in communicating with physicians by email. For example, 80% of patients in a family practice clinic expressed this interest, and most reported that their email address changed less frequently than their home address or telephone number (Virji et al., 2005).

Research shows there are compelling reasons to use email to effectively communicate with patients. Benefits of email include increased efficiency, strengthened patient/provider communication, and more informed decision making—all of which affect patient behavior and, ultimately, health outcomes. Other advantages of email include:

- Email provides a written record of the exchange and enables patients to focus on questions they want to ask and ask follow-up questions. Rather than trying to recall healthcare provider’s answers from an in-person or telephone conversation, they can review the written reply at any time (Ball & Lillis, 2001).

- Email communication does not require both parties to be available at the same time, and allows “continuous access and more active participation in patients’ healthcare by patients and their families”(Mann, Lloyd-Puryear, & Linzer, 2005, p. S316).

In addition to one-to-one email communication, there are services that send patient education to a wider audience. Some 14% of U.S. Internet users have signed up to receive emails about health or medical issues (Fox, 2011). For example, at UbiCare, we provide one such service to hospitals in several health sectors, enabling providers to:

- Automatically send health information that is both condition-specific and stage-specific (i.e., tied to where the patient is in his/her specific timeline, such as week of pregnancy, child’s age, or weeks pre- or post-op), as well as hospital-specific, with the ability to customize messages

- Send specific messages to segments of a patient database (e.g., health alerts or reminders based on stage; seasonal reminders such as flu clinics; announcements of new procedures or protocols; or logistical information such as hospital parking lot closures)

- Create and sustain direct communication between patients and nurses to address questions or concerns

- Manage and measure usage and create reports about enrollment and usage trends

...because email communication has been used in healthcare for some time, there is evidence of its benefits... Not all health-related email services offer the same features, but because email communication has been used in healthcare for some time, there is evidence of its benefits, which we will discuss in a later section. Our experience with UbiCare has not only shown improved sense of patient self-care and connection to the care institution (Deloitte, 2011), but also savings in nursing time, and a reduction in unnecessary emergency room visits through use of an automated email service for condition- and stage-specific patient education (UbiCare, 2010).

Social Media. While the use of social networks, including Facebook® and Twitter®, is relatively new in healthcare, it represents an important opportunity for the e-communication effort in any healthcare setting. Because of its newness, however, what is appropriate and productive is not always clearly established, although leading healthcare providers have made strides by adopting clear policies of use designed to protect patients, staff and the institution.

What is well established is that social media, in the personal as well as the professional realm, is here to stay. Consider this: a recent survey of 1,040 young adults ages 18 to 24 revealed that 80% are likely to share health information on social networks, and almost 90% said they trust health information found through their networks (PriceWaterhouseCoopers, 2012).

When used appropriately, social media can be a powerful adjunct to other communication strategies. Here are just a few examples:

- Connecting with colleagues worldwide through social networks can be a source of learning for nurses. However, nurses must be as mindful in these forums, as they are in personal social networks, about how they present themselves and represent their employers.

- Posts on hospital Facebook® pages can provide followers of the page with helpful health and wellness information while also forging an ongoing relationship with them. In addition, private, invitation-only Facebook® pages can provide an effective forum for healthcare providers to interact with and even manage specific populations of patients with shared conditions and concerns.

- Following others (even without posting) can be an excellent source of education. The American Nurses Association cites its own Facebook page, as well as several others, as good sources of news and connection. Twitter® can also be a source of frequent, topic-specific updates.

- Finding healthcare information on Twitter® can be enhanced by knowing the hashtags for which to search (a hashtag is a keyword preceded by a pound sign, such as #BreastCancer). The Healthcare Hashtag Project (Symplur, n.d.) maintains a growing catalog of these tags to help healthcare professionals use Twitter® more effectively.

- LinkedIn® is an excellent source for professional networking and connection.

So far, adoption of social media by healthcare providers has typically been under the control of marketing departments and has been used primarily for community relations. There are quite a few institutions that are doing a lot with social media, as tracked by the “Hospital Social Network List” at Found in Cache (Bennett, 2012) and by the UbiCare Facebook® Engagement Quotient Chart for Healthcare (TPR Media, 2011). So far, adoption of social media by healthcare providers has typically been under the control of marketing departments and has been used primarily for community relations. But it has much greater potential, especially with regard to initiatives such as invited (also known as secure) Facebook® pages focused on specific conditions.

One impediment to realizing this potential has been that, while patients like to read about health information online, including social networks, they are more reticent to post about health. According to Pew Research, 34% of Internet users (25% of U.S. adults) have read about someone else’s health experience online (Fox, 2011). But only 6% of Internet users have posted questions or comments about health online. However, vetted, research-based education; timely clinical information; best practices (such as hand washing); and community outreach have great and largely untapped value in this medium.

Text and Other Methods of Short Message Delivery. Text messaging, which enables one-to-one exchanges of short messages or broadcasts to a large audience, has several attributes applicable to healthcare (Terry, 2008). Among them are:

- Convenience - cellphones are routinely on hand and switched on

- Ubiquity - most people have a mobile device with text capability

- Immediacy - recipients are more likely to read a message and take action right away

- Communication - two-way communication capability provides opportunities for direct engagement

- Monitoring - can be used not just for communication, but also to monitor/report symptoms

- Measurability - results can be tabulated and measured

- Dissemination - can be used for emergency alerts

- Multimedia - texts can include links to audio, video or other websites

Perhaps the most obvious application of text messaging to patients in the healthcare setting is for reminders, alerts, or frequently asked questions. Perhaps the most obvious application of text messaging to patients in the healthcare setting is for reminders, alerts, or frequently asked questions (FAQs). The Internet Sexuality Information Services (ISIS) project, a public health initiative to provide sexual advice to young people, offers a compelling example in terms of patient education. In its first quarter, the project spawned 4,500 questions, more than half of which were referred to further information and resources. The director of the program stated that the privacy of the cell phone, plus the ability to immediately turn referral information into action (by making an appointment or reading more on a website) were contributors to the program’s high response rate; after the first trial, they replicated the program in additional cities (Terry, 2008). The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services sees the promise in this medium and has created the Text4Health Task Force aimed at “encouraging and developing health text messaging initiatives” (Merrill, 2011, para. 2). Some recent initiatives include smoking cessation messages (the National Cancer Institute’s QuitNowTXT initiative); diabetes education and management; and support and education for eczema patients.

While text messaging has demonstrated success and vast potential for connecting with patients, it also has use among hospital staff. A recent pilot study at Sarasota Memorial Healthcare System used iPod Touches to reduce the number of overhead pages (they used a specialized app and wireless rather than cellular connectivity, but the concept is the same). The floor on which nurses used the iPods reduced the number of pages over an eight-hour period from 172 to 38. This improved quality of care by creating a quieter environment for recovering patients and providing a more efficient method for paging (Strategies for Nurse Managers, 2012).

In another study, adolescents and young adults with diabetes were randomized to receive email or text messages to check and submit their blood glucose levels. Both systems were well received. However, during the first month, cell phone users using text messaging submitted twice as many blood test results as email-receivers (Hanauer, Wentzell, Laffel, & Laffel, 2009).

Electronic Health Records. The structures and systems for electronic health records (EHR) are now being built and implemented all over the country. Most healthcare providers have not yet worked out how they will be used, but if nurses are to be the connectors, now is the time to ensure that the implementation of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ (CMS) “meaningful use” requirements for patient care is informed by what nurses know will be needed (Blumenthal, 2009).

Change is being mandated and it is likely to alter the structures and the way of “doing business” in our healthcare system (Steinbrook, 2009; Blumenthal, 2009 and Department of Health and Human Services, 2012). As a result, not only has a new market of information technology been created, its associated electronic connections—which enhance contact with, access to and support for patients, as well as providers (particularly nurses) and the healthcare institution itself—are playing a role in the transformation of healthcare. As noted in a recent Advance for Nurses article, “Having such data as diagnoses, prescriptions, and appointment schedule bundled at one’s fingertips for the patient and provider’s perusal continues to prove increasingly invaluable, particularly for those patients living with chronic health conditions such as diabetes, cancer or HIV/AIDS” (Coyle, 2012, para. 7).

Implementations and capabilities vary, but EHR may ultimately prove to be the most powerful communication tool of all, especially when used in combination with the other e-communication channels. Rather than being passive receivers of data, such systems can also deliver information and alerts to the healthcare team in real-time. In one example, a patient portal enabled nurses to send notes to patients to see their results and read their comments. Implementations and capabilities vary, but EHR may ultimately prove to be the most powerful communication tool of all, especially when used in combination with the other e-communication channels (Coyle, 2012).

A case study of a technology developed in 1999 provides an excellent example of how an EHR combined with an email delivery system of patient education can improve outcomes. In this initiative, Intermountain Healthcare in Salt Lake City, Utah, sought to reduce unnecessary, early, elective, labor inductions, which are not good for mother or baby and increase the risk of C-sections. Their innovation sought to:

- Develop a new hospital guideline on early induction

- Have the charge nurse, rather than the unit clerk, perform the scheduling

- Generate electronic flags (using their own charging program) if a patient is inappropriately scheduled

- Notify the provider that the induction cannot be scheduled

- Provide patient education about the risks of early induction

- Generate reports

Email or other patient education and communication can help to demystify the medical jargon and give patients the support needed to make the most of their newfound medical access. This innovation was quite successful, resulting in a reduction of early inductions from 28% of all inductions to fewer than 2% over a 12-year period. Cost savings were realized as well, with insurers saving an estimated $1.7 million over five years (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ], 2011).

Electronic patient education is part of the menu set of CMS’s “meaningful use” (hospitals and private practices must implement a portion of them). The above example is just one way it is possible to reduce unnecessary procedures using a combination of an EHR and an electronic patient education component; sending the patient education electronically could be automated when the patient meets certain criteria.

This combination clearly has potential to improve outcomes and lower costs by:

- Saving nursing time through automation

- Reducing emergency room visits and hospital stays through reminders and education

Perhaps the most important aspect of understanding EHR is the fact that, for many patients, getting access to their medical records can be scary and confusing, especially if there is no context in which to understand and put them in perspective. Email or other patient education and communication can help to demystify the medical jargon and give patients the support needed to make the most of their newfound medical access.

Effectiveness of E-Communication in Healthcare

Apart from the examples above, what evidence do we have of the effectiveness of e-communication for health? While evidence is slim on social media, there is ample evidence of the impact of text and email in health. Consider these examples briefly described in Table 5.

Table 5. Evidence of E-Communication Effectiveness

|

Channel |

Study Basics |

Suggests… |

|

Email and website |

11 of 19 studies reviewed showed that periodic electronic prompts and reminders to carry out healthy behaviors, such as physical activity and diet changes, showed a positive short-term impact. These interventions were most effective when they were frequent and included contact with healthcare staff. (Fry & Neff, 2009) |

Frequent and personal contact improves effectiveness of electronic prompts. |

|

Email and website |

In a single-site study of an online nurse electronic coaching systems for chronic pain, depression, and impaired mobility, 35% of participants exchanged emails with the nurse e-coach; 88% of these were interested in further coaching. (Allen, Iezzoni, Huang, Huang, & Leveille, 2008) |

Email contact with nurse e-coach establishes deeper connection. |

|

Text and email |

In a study of adolescent weight management, adolescents responded most quickly to texts, rather than to email messages; 91% of all responses were relevant to the health message patients received. Most rated this contact as “somewhat helpful.” Messages about healthy eating and those ending with “please reply” got the best response. (Korman et al, 2010) |

SMS and email is a useful adjunct to other interventions in adolescents. |

|

Email and website |

In a study of a web-based eHealth application, DiabetesCoach, patient-nurse email contact was the most appealing part of the program. It made patients feel they were closely monitored and more inclined to play an active role in their disease management. (Niiland, van Gemert-Piinen, Kelders, Brandenburg, & Seydel, 2011) |

Direct electronic contact with nurses may improve patient compliance to self-care regimens. |

|

Email, text and social media |

A survey of asthma patients ages 12 to 40 showed that Facebook®, text, and email were used at least weekly by 65%, 77%, and 82% of respondents (respectively). Email was the preferred channel to send and receive health information. Some interest was seen in using SMS or Facebook®, although respondents were concerned about privacy on social media sites; they also felt these sites were more apt for social connections. (Baptist et al, 2011) |

Email, text, and Facebook® show potential in health care e-communication. |

Regardless of medium, any patient e-communication program must be monitored and measured on an ongoing basis to determine efficacy. Return on investment goals (whether in time/money or outcomes) should be set, and there should be an ongoing way to assess whether the program is meeting those goals and to adjust tactics as needed.

Conclusion: Vision or Mandate, Nurses Will Be Key

Some of this technology will find nurses; others of it nurses will have to take it upon themselves to find and adopt. So what does all of this mean for nursing and healthcare systems? Some of this technology will find nurses; others of it nurses will have to take it upon themselves to find and adopt. Either way, these tools will continue as a growing presence in patient care. The questions are, to what extent will the role nurses play in use of technology be foisted upon them, and/or will they have a significant say in how this technology is used?

Experience suggests that nursing leaders—and those who discover they can lead in this way—will seek the opportunities and efficiencies that electronic connections afford both their patients and them. For some it may become yet another burden nurses must manage. But for more and more, it will mean embracing, then guiding, electronic communications with patients and, thereby hopefully improving care and saving nursing time. With the increase of care taking place outside of the hospital walls, nurses are and will continue to be in a unique position to use technology in a positive way.

Today’s nursing leaders can maximize the benefits of electronic tools by educating themselves and their staff, and working with others in their organizations, particularly those with expertise in healthcare informatics, to better understand the potential uses, challenges, and benefits. But they must be proactive in harnessing this opportunity.

“Nurses are in a really good position to get right in there and be the middlemen,” University of Maryland’s Wilson says, “Not as brokers, not as controllers or gatekeepers, but as guides to this world of information and knowledge growth. Whether it’s through text or social media or something else, nurses are in a perfect position to do that” (Personal communication, M. Wilson, April 24, 2012).

Authors

Betsy Weaver, EdD

E-mail: betsyw@tprmedia.com

Betsy Weaver, EdD, is a nationally recognized thought leader and innovator; first in niche publishing for parents and baby boomers; and for the past decade in healthcare—patient education and communication. With the formation of TPR Media in 2002, Weaver created the first email services for hospitals designed to enhance care connections with patients and streamline processes for staff. A 2012 “Enterprising Woman of the Year” award-winner, Weaver’s foresight and leadership at TPR has provided healthcare leaders with an efficient tool to support the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ “meaningful use” rules for condition-specific patient education resources and for accountable care organizations. Building on the efficacy of the email services, Weaver created the first hub platform for healthcare, incorporating email, social media, text messaging, and web services. Weaver holds a master’s in education and a doctorate in social policy and trend analysis from Harvard University, a master’s from Bank Street College of Education, as well as a BA from Lake Forest College.

Bill Lindsay

E-mail: bill@tprmedia.com

Bill Lindsay has 25 years’ experience leading editorial operations for targeted, multi-platform media ventures, creating award-winning content in a variety of subject areas, primarily health, education, parenting, and life-stage issues. He has been a featured speaker at publishing and social media events and twice served on the board of directors of the Parenting Publications of America. He holds a bachelor’s degree in history and journalism from the University of Richmond and is a former fellow at the American Press Institute and the Casey Journalism Center for Children and Families at the University of Maryland.

Betsy Gitelman

E-mail: betsyg@tprmedia.com

Betsy Gitelman has been writing and editing for TPR Media since 2005 and serves as the firm’s corporate editor. A professional writer for over 25 years, she has extensive experience as a researcher and has brought this experience at TPR on a wide range of health-related topics. Gitelman is the author of a history of the Harvard School of Dental Medicine, has written and edited articles for the Department of Health Care Policy at Harvard Medical School, and has published several essays in The Boston Globe magazine. She holds a bachelor’s degree in communications studies from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

© 2012 OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing

Article published September 30, 2012

References

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ]. (2011). Electronic alerts, patient education, and performance reports improve adherence to guidelines designed to reduce early elective inductions. Retrieved from www.innovations.ahrq.gov/content.aspx?id=3161.

Allen, M, Iezzoni, L. I., Huang, A., Huang, L., & Leveille, S. G. (2008). Improving patient-clinician communication about chronic conditions: Description of an internet-based nurse e-coach intervention. Nursing Research, 57, 107–112.

Anderson, C., Barthold, M.F., Duecker, T., Guinn, P., MacCallum, R., Sensmeier, J., (2012) Nursing informatics 101. Proceedings of the HIMSS Nursing Informatics: Empowered Care Through Leadership and Technology. Retrieved from: www.himss.org/handouts/NI101.pdf

Ball, M. J.,& Lillis, J. (2006). E-health: Transforming the physician/patient relationship. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 61, 1–10.

Baptist, A. P., Thompson, M., Grossman, K. S., Mohammed, L., Sy, A., & Sanders, G. M. (2011). Social media, text messaging, and email preferences of asthma patients between 12 and 40 years old. The Journal of Asthma, 48, 824–830.

Bennett, E. (2012). Hospital social network list. In Found in cache. Retrieved from http://ebennett.org/hsnl/.

Blumenthal, D. (2009) The federal role in promoting health information technology. The Commonwealth Fund, 2, Retrieved from www.commonwealthfund.org/Publications/Perspectives-on-Health-Reform-Briefs/2009/Jan/The-Federal-Role-in-Promoting-Health-Information-Technology.aspx.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2010). Chronic diseases and health promotion. Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/overview/index.htm.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). Rising health care costs are unsustainable. Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/workplacehealthpromotion/businesscase/reasons/rising.html.

Christensen, C. (1997). The innovator’s dilemma. Cambridge, Ma: Harvard Business Review Press.

Cohen, R A, Stussman B. (2010). Health information technology use among men and women aged 18-64: Early release of estimates from the national health interview survey, January–June 2009. Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/healthinfo2009/healthinfo2009.htm.

Coyle, S. (2012). Conquering the fear of technology. Advance for Nurses. Retrieved from http://nursing.advanceweb.com/Features/Articles/Conquering-the-Fear-of-Technology.aspx.

Deloitte Consulting & Zogby International. (2011). Evaluation of email messaging service for expectant and new military families, conducted for the Department of Defense (TRICARE).

Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.) Centers for medicare & medicaid services, medicare and medicaid incentives and administrative funding. Retrieved from www.hhs.gov/recovery/reports/plans/pdf20100610/CMS_HIT%20Implementation%20Plan%20508%20compliant.pdf

Feldman, P. H., Murtaugh, C. M., Pezzin, L. E., McDonald, M. V., Peng, T. R. (2005). Just-in-time evidence-based e-mail “reminders” in home health care: Impact on patient outcomes. Health Services Research, 40, 865–885.

Fox, S. (2011). The social life of health information, 2011. In Pew Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved from http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2011/Social-Life-of-Health-Info.aspx.

Fox, S. (2012). Pew Internet: Health. In Pew Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved from www.pewinternet.org/Commentary/2011/November/Pew-Internet-Health.aspx

Fry, J. P., Neff, R. A. (2009). Periodic prompts and reminders in health promotion and health behavior interventions: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 11(2), e16.

Hanauer, D. A., Wentzell, K, Laffel, N, Laffel. L. M. (2009). Computerized automated reminder diabetes system (CARDS): E-mail and SMS cell phone text messaging reminders to support diabetes management. Diabetes Technology & Therapeutics, 11(2), 99–106.

Haynes, R. B., Ackloo, E., Sahota. N., McDonald. H. P., Yao, X. (2008). Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 16(2), CD000011.

Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society [HIMSS]. (2007). 2007 HIMSS nursing informatics survey. Retrieved from www.himss.org/content/files/surveyresults/2007NursingInformatics.pdf.

Korman, K. P., Shrewsbury, V. A., Chou, A. C., Nguyen, B., Lee, A., O'Connor, J., … Baur, L. A. (2010). Electronic therapeutic contact for adolescent weight management: The Loozit® study. Telemedicine Journal and E-Health, 16(6), 678–685.

Mann, M. Y., Lloyd-Puryear, M. A., Lizer, D. (2006). Enhancing communication in the 21st Century. Pediatrics, 117, 315–319.

Marco, J., Barba, R., Losa, J. E., de la Serna, C. M., Sainz, M., Lantigua, I. F., de la Serna, J. L. (2005). Advice from a medical expert through the Internet on queries about AIDS and hepatitis: Analysis of a pilot experiment. PLoS Medicine, 3, e256.

Merrill, M. (2011). HHS Text4Health ,mHealth initiatives focus on smoking cessation. In Healthcare IT News. Retrieved from www.healthcareitnews.com/news/hhs-text4health-mhealth-initiatives-focus-smoking-cessation.

Niiland, N., van Gemert-Piinen, J. E., Kelders, S. M., Brandenburg, B. J., Seydel, E. R. (2011). Factors influencing the use of a Web-based application for supporting the self-care of patients with type 2 diabetes: A longitudinal study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 30(13), e71.

Orr, G. (2003). Diffusion of innovations, by Everett Rogers (1995). Retrieved from www.stanford.edu/class/symbsys205/Diffusion%20of%20Innovations.htm

Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project (2011). How Americans Use Their Cell Phones. Tracking Surveys, April 26–May 22, 2011. Retrieved from www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2011/Cell-Phones/Section-1/How-Americans-Use-Their-Cell-Phones.aspx

Pew Research Center (2012). Global digital communication: Texting, social networking popular worldwide. Retrieved from www.pewglobal.org/2011/12/20/global-digital-communication-texting-social-networking-popular-worldwide/.

Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project (2012a). Adult gadget ownership over time (2006-2012). Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/Trend-Data-(Adults)/Device-Ownership.aspx

Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project. (2012b). Demographics of internet users. Retrieved from: www.pewinternet.org/Static-Pages/Trend-Data-(Adults)/Whos-Online.aspx

Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project. (2012c). Changes in cell phone internet use by demographic, 2009–2012. Tracking surveys, March 15–April 3, 2012, and March 26–April 19, 2009. Retrieved from http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Cell-Internet-Use-2012/Main-Findings/Cell-Internet-Use.aspx

Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project (2012d). A majority of adult cell owners (55%) now go online using their phones. Tracking Surveys, March 15–April 3, 2012. Retrieved from http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Cell-Internet-Use-2012/Main-Findings/Cell-Internet-Use.aspx

Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project (2012e). What internet users do online. Retrieved from www.pewinternet.org/Static-Pages/Trend-Data-(Adults)/Online-Activites-Total.aspx

Purcell, K., (2012). Books or Nooks? How Americans’ reading habits are shifting in a digital world. Proceedings of the Ocean County Library Staff Development Day. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/~/media/Files/Presentations/2012/May/Books_or_Nooks_PDF.pdf

PriceWaterhouse Coopers [PwC]. (2012). Social media “likes” healthcare: From marketing to social business. Retrieved from www.pwc.com/us/en/health-industries/publications/health-care-social-media.jhtml.

Ritterband, L. M., Borowitz, S., Cox, D. J., Kovatchev, B., Walker, L. S., Lucas, V., Sutphen, J. (2005). Using the internet to provide information prescriptions. Pediatrics, 116, e643–647.

Rogers, E. (2003). The diffusion of innovations. (5th ed.). New York, NY: The Free Press.

Smith, A. (2012). Cell internet use 2012. In Pew Internet and American Life Project. Retrieved from http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Cell-Internet-Use-2012.aspx

Steinbrook, R. (2009) Health care and the American recovery and reinvestment act. The New England Journal of Medicine, 360 (p. 1057-1060). Retrieved at www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp0900665

Stevens, V. J., Funk, K. L., Brantley, P. J., Erlinger, T. P., Myers, V. H., Champagne, C. M.,… Hollis, J. F. (2008). Design and implementation of an interactive website to support long-term maintenance of weight loss. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 10, e1.

Strategies for Nurse Managers. (2012). Nurses use iTouch and iPhones to communicate and stay connected. Retrieved from www.strategiesfornursemanagers.com/ce_detail/242233.cfm.

Symplur. (n.d.). The healthcare hashtag project. Retrieved from http://www.symplur.com/healthcare-hashtags/

Terry, M. (2008). Text messaging in healthcare: The elephant knocking at the door. Telemedicine Journal and E-Health, 14, 520–524. DOI: 10.1089/tmj.2008.8495.

UbiCare. (2010). Survey of 98 military healthcare professionals measuring the value of email messaging service for new and expectant parents to US Department of Defense clinicians, nurses and staff at 30 military treatment facilities. [Internal unpublished document].

TPR Media, LLC. (2012). UbiCare communication solutions for healthcare. What’s your EQ?: A look at healthcare’s Facebook® engagement. Retrieved from https://ubicare.com/engagement.

Virji, A., Yarnall, K. S., Krause, K. M., Pollak, K. I., Scannell, M.A., Grandison, M., Ostbye, T. (2005). Use of email in a family practice setting: opportunities and challenges in patient- and physician-initiated communication. BioMed Central Medicine, 4, 18.