Nurses and advanced practice providers play a critical role in improving health outcomes globally, yet they remain underrepresented in major global health organizations. In 2022, an electronic survey was conducted among nurses and advanced practice providers at the University of California, San Francisco’s West and East Bay locations to assess their expertise and interest in working with partners in low- and middle-income countries and to identify barriers to their engagement in global health interventions. The survey revealed significant obstacles, including concerns about taking time off work, a lack of clear pathways to engage in global health, and challenges in securing funding for travel. The loss of potential income while working abroad was also cited as a barrier among participants. The survey’s results underscored the need for a centralized platform for nurses and advanced practice providers to share their expertise and foster collaborations. In response to these findings, the Center for Global Nursing at UCSF was established. The center provides opportunities in global research, partnerships, and education, creating pathways for meaningful involvement in global health initiatives. Further research is necessary to explore how the underrepresentation of nurses and advanced practice providers in academic global health initiatives impacts health outcomes on a global scale.

Key Words: nursing, global health, barriers, advanced practice providers, center for global nursing, Low-income country, middle-income country, UCSF nursing

...nurses participate in healthcare leadership and research that enhances care quality, influences policy, and develops initiatives to tackle global health challenges.Nursing, with a global workforce of over 29 million, plays a key role in shaping population health through direct patient care, advancing research, and leading initiatives (World Health Organization, 2024). Nurses are vital to healthcare systems and often serve as the primary or sole healthcare providers for many, making the quality of nursing care essential for achieving optimal patient outcomes and improving public health (World Health Organization, 2024). Outside the bedside, nurses participate in healthcare leadership and research that enhances care quality, influences policy, and develops initiatives to tackle global health challenges. Their ability to navigate complex healthcare environments and build trusting relationships with patients positions them as key contributors in closing population health gaps and implementing effective healthcare solutions. Therefore, the role of nurses is crucial not only in individual patient care but also in the larger effort to improve population health globally (Cole Edmonson et al., 2017; Salvage & White, 2020; World Health Organization, 2024).

The World Health Organization and the National Academy of Sciences have acknowledged the significant impact of nursing and have urged nurses to participate, lead, and act as agents of change in global health equity efforts (The National Academies Press, 2020; World Health Organization, 2020). However, despite constituting 59% of the global health workforce, nurses encounter considerable barriers to involvement in global health initiatives (Rosa et al., 2022). They are underrepresented in major global health organizations and often excluded from leadership and decision-making roles where they could make a meaningful difference (World Health Organization, 2019). This exclusion from leadership not only limits nurses' potential contributions to global health solutions but also sustains a healthcare system that does not fully utilize the expertise and insights of its largest workforce. Furthermore, nurse-led organizations often lack the resources and influence compared to those led by physicians, restricting their ability to influence policies and strategies on a global level (Salvage & White, n.d.). Additionally, many nurses spend most of their professional time delivering direct patient care, leaving limited opportunities for them to participate in broader health initiatives (Westbrook et al., 2011). As a result, their vital perspectives on patient care, health equity, and community outreach—areas in which nurses excel—are frequently absent from high-level discussions and decisions in global health.

The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), with its extensive network of nurses and global health experts, is well positioned to bridge this gap and involve nurses in high-level global health discussions and initiatives. UCSF employs 4,611 nurses and over 1,000 advanced practice providers (APPs) (UCSF Department of Nursing, 2024; University of California, San Francisco, n.d.). It also hosts some of the top global health experts in the United States (UCSF Institute for Global Health Sciences, n.d.). During the COVID-19 pandemic, there was an urgent call for nursing involvement in multidisciplinary global efforts to improve global health (National Academy of Medicine; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2021; World Health Organization, 2020). However, at that time, little was known about how engaged UCSF nurses and APPs were in global health initiatives, either within UCSF or elsewhere. There was also limited information about which nurses or APPs possessed specific expertise or interest in global health sciences. Furthermore, no formal assessment had been conducted to identify barriers preventing their participation in global health efforts. To fill these knowledge gaps, a survey was sent in 2022 to all UCSF nurses and APPs to gather data on their practice profiles, the extent of their global health experiences, and their expertise in global health sciences. This survey aimed to understand UCSF nurses' and APPs' perceived obstacles to engaging in global health work, providing valuable insights into the untapped potential of nurses and APPs in UCSF's global collaborations and guiding a strategic plan to increase future nursing involvement in global health sciences.

Methods

A cohort study design was used to describe the experiences, interests, and barriers to global health engagement among nurses and APPs at UCSF. All nurses and APPs working at UCSF's West and East Bay locations were eligible to participate. For this study, APPs were defined as advanced practice nurses, including certified nurse midwives (CNMs), certified registered nurse anesthetists (CRNAs), nurse practitioners (NPs), and physician assistants (PAs) (University of California, San Francisco, n.d.). Participants were invited by email to complete an online survey. The survey was distributed using the modified Dillman method and administered through the Qualtrics platform (Hoddinott & Bass, 1986; Qualtrics, 2005). The initial survey distribution took place in November 2022, with a reminder email sent two weeks later. The survey remained open for four weeks, closing in December 2022.

The survey consisted of 18 questions, including both multiple-choice items and open-ended response options. Respondents answered questions across three categories: demographics and UCSF clinical expertise, involvement in the global health field, and identification of barriers to participating in global health initiatives. Most survey questions were evaluated as categorical variables with a set number of response options, and respondents were asked to select all options that applied to them. A free-text box was available for respondents to elaborate if the predefined options did not fully capture their experiences. Several questions were presented as a five-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” to more accurately capture participants' experiences and perceptions of working in global health (Likert, 1932). The survey data was analyzed using descriptive statistics. Categorical variables and binary "yes/no" questions were examined as a percentage of the total sample (n = 215). Data was reviewed for commonalities and trends using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, 2024).

Results

3.1 Participant demographics and practice profiles

Two hundred and fifteen nurses and APPs completed the survey. Since most questions asked participants to select all options that applied to them, some survey questions had more responses than the total number of participants. Nearly three-quarters (n = 151, 70.2%) of all respondents were employed full-time in a clinical position at the time of data collection, while about 18% (n = 39) worked in a part-time clinical role. A few individuals held a per diem clinical position (n = 14, 6.5%). Several respondents also had a part-time School of Nursing faculty position (n = 3, 1.4%), an adjunct or non-salary School of Nursing faculty role (n = 10, 4.7%), or another position (n = 13, 6.0%). Those who selected “other” indicated they were employed full-time in a non-clinical or administrative role. Participants' roles at UCSF varied. Over half of the responses (n = 123, 57.2%) were from individuals working as registered nurses. Approximately one third of respondents (n = 66, 30.7%) were employed as nurse practitioners. The next most represented role was nurse managers/leaders (n = 22, 10.2%), followed by nurse educators (n = 9, 4.2%). The remaining respondents included physician assistants (n = 6, 2.8%), nurse midwives (n = 2, 0.9%), nurse anesthetists (n = 5, 2.3%), and clinical nurse specialists (n = 6, 2.8%).

Respondents exhibited a wide range of clinical expertise and served diverse patient populations. Seventy-six individuals specialized in pediatrics (35.3%), while sixty focused on adult/geriatrics populations (27.9%). The areas of expertise varied, with sixty-seven individuals working in critical care (31.2%), thirty-six in cardiac/cardiac surgery (16.7%), twenty-six in hematology/oncology (12.1%), and twelve in reproductive health/obstetrics (5.6%). Only one respondent indicated that they specialized in acute rehabilitation (0.5%). Other fields of expertise included care across the lifespan (n = 18, 8.4%), neonatology (n = 11, 5.1%), emergency medicine (n = 18, 8.4%), perioperative care (n = 28, 13.0%), medical/surgical care (n = 39, 18.1%), neurosciences (n = 24, 11.2%), and various "other" fields (n = 54, 25.1%). Respondents’ write-in responses for the "other" category included public health, research, primary care, psychiatry, pain management, infectious disease, and occupational health.

Table 1. Participant Practice Profiles

|

I am employed by |

n |

% |

|---|---|---|

|

UCSF Medical Center: Parnassus |

90 |

41.9% |

|

UCSF Medical Center: Laurel Heights |

1 |

0.5% |

|

UCSF Medical Center: Mount Zion |

20 |

9.3% |

|

UCSF Medical Center: Mission Bay (Adult) |

35 |

16.3% |

|

UCSF Benioff Children's Hospital: San Francisco |

55 |

25.6% |

|

UCSF Benioff Children's Hospital: Oakland |

30 |

14.0% |

|

Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center |

3 |

1.4% |

|

UCSF School of Nursing |

9 |

4.2% |

|

Other (write in): |

19 |

8.8% |

|

I am employed in a |

n |

% |

|

Full time clinical position (0.9 - 1.0 FTE) |

151 |

70.2% |

|

Part time clinical position (0.2 - 0.8FTE) |

39 |

18.1% |

|

Per Diem clinical position |

14 |

6.5% |

|

Part time School of Nursing faculty position |

3 |

1.4% |

|

Adjunct/Non-Salary School of Nuring faculty position |

10 |

4.7% |

|

Other: (write in): |

13 |

6.0% |

|

My role at UCSF is |

n |

% |

|

Registered Nurse |

123 |

57.2% |

|

Nurse Practitioner |

66 |

30.7% |

|

Physician Assistant |

6 |

2.8% |

|

Nurse Educator |

9 |

4.2% |

|

Nurse Midwife |

2 |

0.9% |

|

Nurse Anesthetist |

5 |

2.3% |

|

Clinical Nurse Specialist |

6 |

2.8% |

|

Nurse Manager/Leadership |

22 |

10.2% |

|

Faculty of Nursing |

8 |

3.7% |

|

My field of expertise is |

n |

% |

|

Pediatrics |

76 |

35.3% |

|

Critical Care |

67 |

31.2% |

|

Adult/Geriatric |

60 |

27.9% |

|

Other (write in): |

54 |

25.1% |

|

Medical/Surgical Care |

39 |

18.1% |

|

Cardiac/Cardiac Surgery |

36 |

16.7% |

|

Peri-operative Care |

28 |

13.0% |

|

Hematology/Oncology |

26 |

12.1% |

|

Neurosciences (including neurology/neurosurgery) |

24 |

11.2% |

|

Care across a lifespan (both adult and pediatric) |

18 |

8.4% |

|

Emergency Department |

18 |

8.4% |

|

Reproductive health/Obstetrics |

12 |

5.6% |

|

Neonatology |

11 |

5.1% |

|

Acute Rehabilitation |

1 |

0.5% |

3.2 Scope of participant global health experiences

Among all 215 respondents, 23 individuals (10.7%) indicated that they are currently involved in global health efforts or working in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). One hundred and sixteen (54.0%) respondents reported that they are not currently working in an LMIC. However, approximately thirty-seven percent (n=79) of respondents noted that they have previous experience working on global health efforts in LMICs despite not actively working in one at the time of data collection.

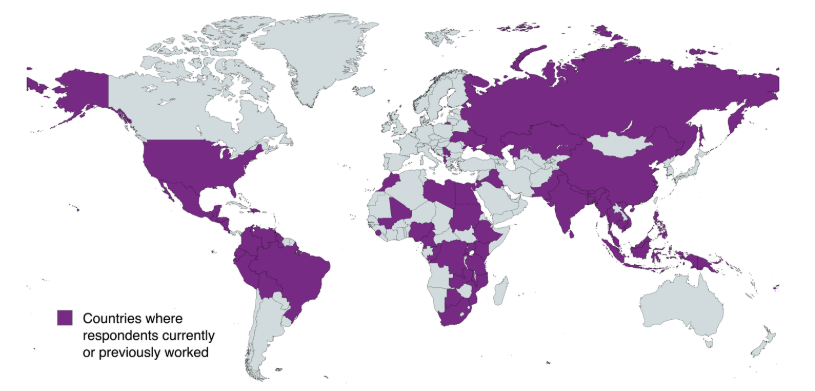

Among participants with previous experience and/or active involvement in global health efforts, many named various international organizations as collaborators...Among participants with previous experience and/or active involvement in global health efforts, many named various international organizations as collaborators, including International Nurses for Nepal, Mending Kids International, the Peace Corps, Nurses for Africa, and the Haitian Health Foundation (Haitian Health Foundation, n.d.; Huffam, 2019; International Nurses for Africa, n.d.; Mending Kids, n.d.; Peace Corps, n.d.). These collaborators were based in both high-income countries and LMICs. Others mentioned their work more generally as “medical missions” and “volunteer work abroad,” while some also reported their health equity efforts locally. Additionally, participants indicated they have worked in 63 countries around the world, either previously or currently (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Distribution of work locations (MapChart, n.d.)

Approximately twenty percent of respondents reported involvement in global health work focused on education and training (n = 49, 22.8%), while an additional twenty-five percent engaged in patient care (n = 55, 25.6%). A sizable portion of respondents worked in program development (n = 35, 16.3%). The remaining respondents were involved in research (n = 7, 3.3%) or selected “other” (n = 5, 2.3%). Those who chose “other” indicated their work related to rural communities, water and waste management, or health statistics.

More than two-thirds of respondents (n = 144, 67.0%) expressed interest in participating in future global health initiatives or working in a low- and middle-income country (LMIC). An additional fifty-nine individuals (27.4%) answered "maybe," with their interest depending on factors such as personal costs, having young children, or being a student at the time of data collection. Six respondents (2.8%) said they would not like to be involved in future global health initiatives or work in LMICs.

When asked about interest in specific global health activities, 139 individuals (64.7%) expressed interest in traveling internationally, while 76 respondents (35.3%) showed interest in global health opportunities that do not involve international travel. Regarding the timing of their participation, 95 participants (44.2%) were interested in opportunities within the next year, compared to 114 participants (53.0%) who preferred opportunities within the next five years. Respondents showed different levels of interest in various types of global health activities: global health research projects (n = 99, 46.0%), capacity-building efforts (n = 68, 31.6%), continuing education opportunities (n = 107, 49.8%), and mentoring programs (n = 48, 22.3%). Interest in funded global health opportunities (n = 91, 42.3%) was higher than interest in volunteer opportunities (n = 77, 35.8%).

3.3 Barriers to entry in global health

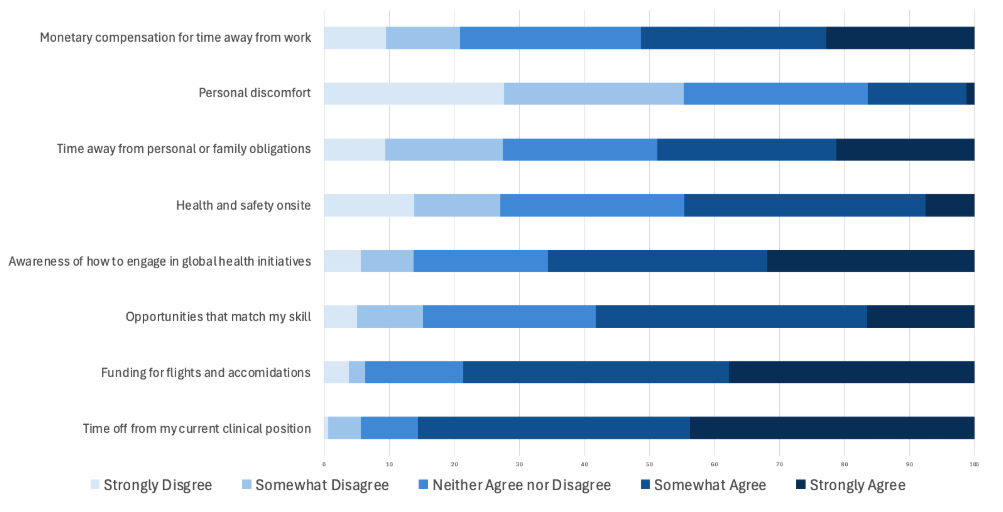

Participants identified several barriers to engaging in global health initiatives, including challenges in securing funding and a general lack of awareness about how to participate. Sixty individuals (37.3%) strongly agreed that limited funds for travel and accommodations prevented their involvement in global health efforts. Regarding the lack of awareness about how to engage, about one-quarter of participants strongly agreed (23.7%) and another quarter somewhat agreed (25.1%) that this was a barrier. Additionally, 66 respondents (30.7%) somewhat agreed that a lack of global health opportunities matching their skill levels discouraged participation.

Participants identified several barriers to engaging in global health initiatives, including challenges in securing funding and a general lack of awareness about how to participate.Seventy respondents (35.3%) strongly agreed that taking time off from their current clinical position was a barrier, while only one individual (0.5%) strongly disagreed. Additionally, thirty-six participants (16.7%) strongly agreed and forty-five (20.9%) somewhat agreed that the lack of monetary compensation while taking time off was a deterrent to engaging in global health. Time away from personal or family obligations was also identified as a significant barrier, with 44 respondents (20.5%) somewhat agreeing and 34 (15.8%) strongly agreeing.

Personal discomfort and health and safety concerns on-site were rarely cited as major barriers. Only 12 individuals (5.6%) strongly agreed that health and safety were serious concerns, while nearly a quarter of participants responded neutrally (20.9%). Similarly, just two respondents (0.9%) strongly agreed that personal discomfort was a barrier, whereas 44 participants (20.5%) strongly disagreed. Figure 2 provides a detailed visualization of the survey responses.

Figure 2. Perceived barriers to working in global health

Discussion

The study’s results show that nurses and APPs at UCSF who took the survey have a wide variety of interests and experiences in global health sciences. Engagement in global health initiatives was seen across different nursing and APP roles, indicating that degree type does not limit those who want to get involved in global health. Respondents also shared diverse global health experiences, having worked in 63 countries. Their involvement with partners ranged from working with grassroots organizations or focusing on research projects to taking part in larger international campaigns.

Despite participants having extensive global health experience, barriers still hinder nurse and APP engagement in the global health sciences. The top three obstacles were the lack of a clear pathway to get involved in global health, the need to take time off from clinical duties, and the financial costs associated with global health work. The idea that monetary costs limit nurses' ability to participate aligns with a 2024 study that identified cost constraints as a major barrier for nurses pursuing career advancement (Baduge et al., 2024). Conversely, participants were much less concerned about personal discomfort, health, and safety issues, indicating they are eager to work in global health if given the right opportunity.

It is possible that the structure of nurses’ and APPs’ workweeks deters them from engaging with the global health field. Nurses and APPs hired to work full-time or a specific number of hours per week do not have the same flexibility to work abroad as those paid based on a set number of work weeks per year (American Institute for Healthcare Management, 2018). This is supported by this study’s finding that being able to take time off work is a significant barrier for nurses and APPs seeking to participate in global health. Therefore, a nurse’s or APP’s employment structure may affect the global health opportunities they can access. A potential solution is to incorporate global health work into unit-based work structures to make it more accessible for nurses and APPs.

This study is the first of its kind, and its results highlight that nurses and APPs are underutilized in the global health field despite their demonstrated interest. To tap into this potential, the UCSF Center for Global Nursing (CGN) was established in 2022 through a collaboration between UCSF Health, the UCSF School of Nursing, and the Institute of Global Health Sciences at UCSF. CGN aims to serve as a platform for nurses and APPs to collaborate, learn, and contribute to global health solutions through education, research, and partnerships (Center for Global Nursing, n.d.).

Using the survey data, CGN successfully identified effective strategies to engage nurses in global health sciences by creating new educational and collaborative opportunities, as well as improving existing ones, for UCSF nurses and APPs to participate in global health solutions. CGN achieves this through its three pillars: research, partnership, and education. It hosts educational programs to introduce its members to fundamental concepts of global health sciences, including cultural humility. The center also maintains partnerships with major organizations like the AMPATH Consortium and the Bixby Center for Global Reproductive Health at UCSF, encouraging members to actively participate in advancing these mutually beneficial collaborations (Center for Global Nursing, n.d.). Regarding research, CGN facilitates global research collaborations and supports its members in conducting research projects to advance nursing practice worldwide.

Without nursing engagement in global health solutions, there is a significant and often overlooked negative impact on health outcomes worldwide (Salvage & White, 2020). This study offers a comprehensive overview of nurses’ and APPs’ involvement in global health sciences at UCSF, but its findings are limited in their applicability to other university hospital systems. Additionally, although the survey included spaces for respondents to provide free-text responses, the study was primarily quantitative. Therefore, it is possible that researchers missed nuances in nursing and APP practice that were not captured through the survey. Finally, since the survey was distributed via email, it may have introduced sampling bias. Further research, including qualitative analysis of nurses’ and APPs' experiences in global health sciences, is needed to better understand their expertise, the underlying factors driving barriers to engagement, and how these barriers might affect global health outcomes at UCSF and other academic institutions.

Conclusion

Nurses and APPs play a vital role in improving global health outcomes, yet they are often overlooked and underused in global health. Despite their crucial importance, nurses and APPs still face barriers that limit their involvement in global health efforts. These barriers include difficulties in taking time off from work and worries about funding for travel and lodging. However, there is significant untapped potential within this group, as nurses and APPs have the expertise and passion needed to become global health leaders and help develop solutions. The UCSF Center for Global Nursing (CGN) provides a promising way to address this by promoting nursing practice worldwide through research, education, and strategic partnerships.

Authors

Rebecca Silvers, DNP, APN, CPNP-AC, CCRN, RNFA

Email: Rebecca.silvers@ucsf.edu

ORCID ID: 0009-0006-1110-9142

Rebecca Silvers is the Founding Director of the UCSF Center for Global Nursing at the Institute for Global Health Sciences and serves as Nursing Lead for UCSF’s WHO Collaborating Centre for Emergency, Critical and Operative Care. An Assistant Clinical Professor at the UCSF School of Nursing, she practices as a pediatric acute care nurse practitioner in critical care and neurosurgery at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospitals. Her global work spans more than 25 countries, partnering with ministries, universities, and professional councils to strengthen the nursing workforce, develop advanced practice, and improve quality of care. She serves as a consultant and technical advisor to the World Health Organization, the United Nations, and the World Federation of Intensive and Critical Care, and as the nursing and advanced practice lead for Open Critical Care. Her scholarship focuses on cultural humility and education and health systems development in low- and middle-income countries, with current work examining policy and institutional barriers that limit U.S. nurses’ engagement in global health.

Maddie Wong, MS

Email: Maddie.wong@ucsf.edu

Maddie Wong earned her undergraduate degree in Health Sciences from Northeastern University and an MS in Global Health Sciences from UCSF's Institute of Global Health Sciences. She is a program coordinator for UCSF's Center for Global Nursing and has worked extensively with nurses and nurse leaders to advance the nursing profession globally. Maddie is committed to improving global health through collaboration, education, and leadership in nursing.

References

American Institute for Healthcare Management. (2018, September 2). Nurse workload, staffing, and measurement. https://www.amihm.org/nurse-workload-staffing-and-measurement/

Baduge, M. S. D. S. P., Garth, B., Boyd, L., Ward, K., Joseph, K., Proimos, J., & Teede, H. J. (2024). Barriers to advancing women nurses in healthcare leadership: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. eClinicalMedicine, 67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102354

Center for Global Nursing. (n.d.). Center for Global Nursing. UCSF Institute for Global Health Sciences. https://globalhealthsciences.ucsf.edu/about-us/our-centers/center-for-global-nursing/

Edmonson, C., McCarthy, C., Trent-Adams, S., McCain, C.,& Marshall, J. (2017). Emerging global health issues: A nurse’s role. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing. https://ojin.nursingworld.org/table-of-contents/volume-22-2017/number-1-january-2017/emerging-global-health-issues/

Haitian Health Foundation. (n.d.). Haitian Health Foundation. https://www.haitianhealthfoundation.org/

Hoddinott, S. N., & Bass, M. J. (1986). The Dillman total design survey method. Canadian Family Physician Le Medecin de Famille Canadien, 32, 2366–2368.

Huffam, E. (2019, December 19). Nurses for Nepal—Australian Himalayan Foundation. https://www.australianhimalayanfoundation.org.au/nurses-for-nepal/

International Nurses for Africa. (n.d.). International Nurses For Africa. https://internationalnursesforafrica.org/our-mission

Likert, R. (1932). A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Archives of Psychology, 22(140), 55–55.

MapChart. (n.d.). MapChart. https://mapchart.net/index.html

Mending Kids. (n.d.). Mending Kids. https://www.mendingkids.org/

National Academy of Medicine; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2021). The future of nursing 2020-2030: Charting a path to achieve health equity (p. 466). https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/25982/the-future-of-nursing-2020-2030-charting-a-path-to

Peace Corps. (n.d.). Peace Corps. https://www.peacecorps.gov

Qualtrics. (2005). Qualtrics (Version May 2024) [Computer software]. Qualtrics. https://www.qualtrics.com

Rosa, W. E., Parekh de Campos, A., Abedini, N. C., Gray, T. F., Huijer, H. A.-S., Bhadelia, A., Boit, J. M., Byiringiro, S., Crisp, N., Dahlin, C., Davidson, P. M., Davis, S., De Lima, L., Farmer, P. E., Ferrell, B. R., Hategekimana, V., Karanja, V., Knaul, F. M., Kpoeh, J. D. N., …& Downing, J. (2022). Optimizing the global nursing workforce to ensure universal palliative care access and alleviate serious health-related suffering worldwide. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 63(2), e224–e236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.07.014

Salvage, J., & White, J. (2020). Our future is global: Nursing leadership and global health. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 28, e3339. https://doi.org/10.1590/1518-8345.4542.3339

UCSF Institute for Global Health Sciences. (n.d.). Our History. UCSF Institute for Global Health Sciences. https://globalhealthsciences.ucsf.edu/about-us/our-history/

University of California, San Francisco. (n.d.). Advanced Practice at UCSF Health. https://advancedpractice.ucsf.edu/home

Westbrook, J. I., Duffield, C., Li, L., & Creswick, N. J. (2011). How much time do nurses have for patients? A longitudinal study quantifying hospital nurses’ patterns of task time distribution and interactions with health professionals. BMC Health Services Research, 11, 319. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-11-319

World Health Organization. (2019). Delivered by women, led by men: A gender and equity analysis of the global health and social workforce. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/311322

World Health Organization. (2020, April 7). WHO and partners call for urgent investment in nurses. https://www.who.int/news/item/07-04-2020-who-and-partners-call-for-urgent-investment-in-nurses

World Health Organization. (2024, May 3). Nursing and Midwifery. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/nursing-and-midwifery