Nurses who work in a hospital setting with seriously ill patients often face ethical dilemmas with no clear solutions but instead difficult choices and uncertainty. Unit-based ethics rounds in the hospital can be tailored to unit specific needs. However, there is a gap in the literature describing how to implement such unit-based rounds. This article describes the experience of nurses who implemented unit-based ethics rounds on one unit using the Integrated Ethics Model as a framework and the feasibility of continuing ethics education into the practice setting. Eight sessions described targeted two of the three Integrated Model’s focus areas: systems and processes, and environment and culture. Seven of the sessions targeted all three foci, and also included decisions and actions. The design of this project maximized exposure to education about ethics in nursing, reflected the unit pace and culture, and has normalized and engaged nurses in ethical thinking and actions. The Integrated Ethics Model provides a feasible framework that can focus unit-based ethics rounds and expand nursing ethics education into practice at the unit level.

Key Words: Ethics rounds, nursing ethics, integrated ethics, ethics education, micro-learning, hospital ethics rounds, unit-based ethics

Nurses who work in a hospital setting with seriously ill patients often face ethical dilemmas with no clear solutions but instead difficult choices with uncertainty, costs, and benefits. Andrew Jameton (1984), a bioethicist, first described moral distress as a complex construct, born of clinical situations where a person knows the ethical action but is prevented from taking it due to internal or external constraints. Put simply, three factors must be present for moral distress: an event (external factors), psychological distress (internal factors), and a relationship between the event and the distress (Hamric & Wocial, 2016; Morley et al., 2019).

Nurses who work in a hospital setting with seriously ill patients often face ethical dilemmas with no clear solutions but instead difficult choices...

The COVID-19 pandemic created persistent and overwhelming clinically challenging experiences that required nurses to navigate the dilemma of responsible resource allocation and high quality clinical and ethical care. (Gebreheat & Teame, 2021, Karakachian et al., 2024) Proactive unit-based ethics support creates open dialogue and provides nurses with the vocabulary, tools, and space to support ethically robust practices (Wocial et al., 2010, 2017). This article describes the experiences of nurses who implemented unit-based ethics rounds using the Integrated Ethics (IE) Model (Danis et al., 2021; Fox et al., 2010). In addition, we explore the feasibility of continuing ethics education integration in the practice environment.

Background

Healthcare ethics committees are not a new phenomenon in the United States. Panels formed in the late 1960s that determined whether patients with terminal kidney disease should have access to dialysis were precursors to ethics committees (Aulisio, 2016). In the 1970s, in the wake of several high-profile court cases, ethics committees were conceptualized as a resource that hospitals used to inform difficult decisions (Aulisio, 2016). In the 1990s, after The Joint Commission (2024) required access to ethics support as a condition of hospital accreditation, the percentage of hospitals with ethics committees increased to 60% (Aulisio, 2016). More recently, a little over 86% of all general hospitals reported having ethics committees or services, with smaller and rural hospitals reporting more limited access to ethics resources (Fox et al., 2022). While the Joint Commission does not dictate what form ethics support must take, research has extensively demonstrated that healthcare providers need moral spaces to reflect, explore, and work through complex ethical obligations that emerge during the process of caring for patients (Hamric & Wocial, 2016).

...research has extensively demonstrated that healthcare providers need moral spaces to reflect, explore, and work through complex ethical obligations...

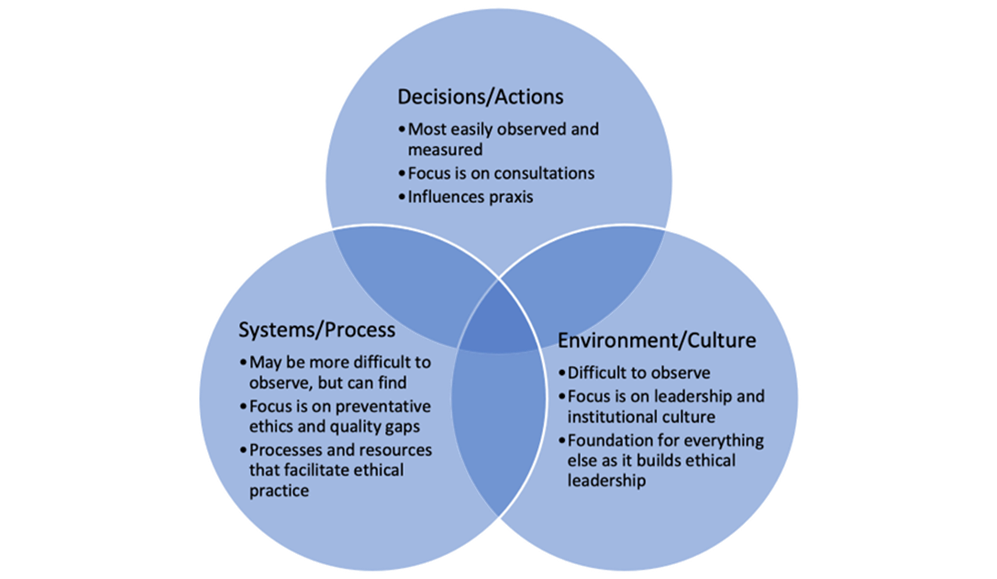

Generally, traditional ethics committees focus on consultations, education, policy formation, and associated decisions and actions (Moon et al., 2019). However, alternative models have been developed. The Integrated Ethics Model, developed by the Veterans Administration (Fox et al., 2010), is a standardized and systematic approach to healthcare ethics with a structure that diverges from the traditional ethics committee-focused model. The IE model focuses on three levels of institutional ethics quality: 1. decisions and actions, 2. systems and processes, and 3. environment and culture; and each of the corresponding functions: ethics consultations, preventive ethics, and ethics leadership (Aulisio, 2016; Fox et al., 2010). Ethics quality is aligned with healthcare quality. (Fox et al., 2010, 2022).

Both the traditional ethics model (Moon et al., 2019) and the integrated ethics model (Fox et al., 2010) recognize the importance of ethics education. The IE model focuses on three levels of institutional ethics qualitySuch education improves outcomes for patients, families, and providers (Firn et al., 2020; Milliken & Grace, 2017; Pavlish et al., 2021). Ethics education can help providers to anticipate and identify potential conflict and, ideally, develop skills to navigate the ethical landscape (Firn et al., 2020). Creating space for ethics discussion can mitigate moral distress and increase ethics self-efficacy, especially for nurses (Pavlish et al., 2021). Nurses with higher levels of ethical awareness and sensitivity related to ethics education are better able to assess if a treatment plan aligns with a patient’s goals and preferences, and can advocate for these goals if this is not the case (Milliken & Grace, 2017).

One approach to ethics education is unit-based ethics rounds. Multi-modal unit-based ethics rounds can address each of the foci of integrated ethics (Schmitz et al., 2018), provide a safe space for participants to work through cases cognitively (Silén et al., 2016), foster development of ethical awareness in nursing practice (Milliken & Grace, 2017), and improve skills to address clinically challenging situations (Wocial et al., 2023). Ethics education has also demonstrated support for building moral Creating space for ethics discussion can mitigate moral distress and increase ethics self-efficacy, especially for nursesagency (Morley & Sankary, 2023; Robinson et al., 2014).

Both across the globe and on the unit, the COVID-19 pandemic and the related increasingly complex patient scenarios, increased moral distress, and widespread burnout have highlighted the need for ongoing ethics education and building moral agency (Hughes & Rushton, 2022). While literature has documented the benefits of ethics education (Firn et al., 2020; Milliken & Grace, 2017; Pavlish et al., 2021), there is little information that details best practices for content, timing, and delivery of unit-based ethics education. For these reasons, we will offer an exemplar below that describes our experience implementing unit-based ethics rounds on a single unit.

One approach to ethics education is unit-based ethics rounds.

Methods

Unit-Based Ethics Rounds Exemplar

Setting and Participants. The setting was a 28-bed surgical-trauma unit in a large academic center in an urban environment. This unit serves patients who have been diagnosed with a serious illness or have experienced trauma. The unit has just under 100 nurses who work full-time or part-time. The unit is a dedicated education unit (DEU) and also includes several junior and senior nursing students. DEUs partner with university nursing programs and have been shown to improve undergraduate nursing education and practice quality (Dimino et al., 2020; Mulready-Shick & Flanagan, 2014). Nurses, nursing students, nursing assistants, other healthcare providers, and ancillary staff were included in the unit-based rounds.

Nurses, nursing students, nursing assistants, other healthcare providers, and ancillary staff were included in the unit-based rounds.

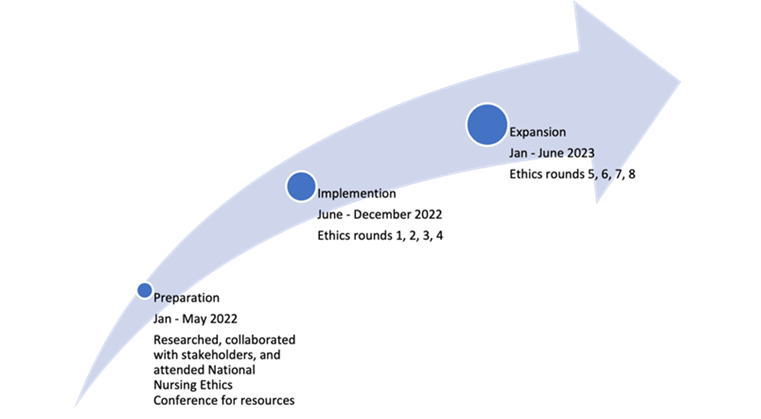

Planning and Implementation. One author (JDM), a member of the site Ethics in Clinical Practice Committee, researched, planned, and implemented the ethics rounds. The process (Figure 1) began with literature searches to investigate unit-based rounds. This was followed by in-person meetings, phone calls, and emails with institutional leadership and other ethics committee members conducting ethics rounds on their respective units to gather information about best and existing practices. Preparation for implementation included observing other unit-based rounds and soliciting possible topics from the nurse director and clinical nurse specialist of the primary unit. Implementing ethics rounds was exempt from review by the institutional review board because this was not a research study, but a unit-based quality improvement project.

Figure 1. Unit-Based Implementation Timeline

Initially, the ethics rounds were envisioned as formal 30 to 45-minute unit-based rounds offered once every three months. However, a few days before the scheduled start date, because of the patient acuity level and pace of the unit, the teaching was integrated into the mid-day huddle to facilitate staff availability. At this point, ethics rounds became known as Bioethics Bites, and consisted of micro-learning sessions and a treat, with the intention of making ethics teaching more palatable and engaging. Additionally, the rounds transitioned from quarterly to monthly rounds.

Because there was no literature regarding the best way to integrate these types of rounds onto a nursing floor, the first few Bites involved a fair amount of trial and error. Following each session, one of the authors who spearheaded the design and implementation of these rounds (JDM) reflected on what worked well and what could have been better. The measure of success was the engagement of the nurses who made time to attend the Bite; whether the topic prompted questions and further insight; and informal feedback from nurses and leadership.

Theoretical Model. The theoretical model underpinning the unit-based rounds was the Integrated Ethics Model. As described, the model, developed by Fox and colleagues (2010), includes three foci (Figure 2) which combine to create ethics quality. The first focus, decisions and actions, is the most measurable of the priorities. It focuses on ethics consultation, educating colleagues about ethical concerns, and the praxis that flows from ethics decisions (Fox et al., 2010).

Figure 2. Overview the Integrated Ethics Model

(Adapted from Fox et al., 2010)

The second focus, systems and processes, overlaps that of decisions and actions. The second focus is less observable but can be found in policy, procedures, and resources that facilitate ethical practice (Fox et al., 2010). Application of this focus seeks knowledge or quality gaps in the institution, such as treatment of employees, research subjects, or resources. The emphasis is on preventive ethics (Fox et al., 2010). In this focus area, interventions target closing the knowledge gaps Fox et al., 2010).

The second focus is less observable but can be found in policy, procedures, and resources that facilitate ethical practice

The third focus, environment and culture, targets the function of ethical leadership. Leadership that empowers employees to do the right thing is considered ethical (Fox et al., 2010). Implementing ethics rounds can demonstrate that ethics quality is a priority of facility leaders. Ethical leadership improves employee and patient satisfaction and productivity (Barkhordari-Sharifabad et al., 2018).

Innovation and Modification. After observing ethics rounds on another unit, the first Bioethics Bites was created with a similar formal format, using a presentation of electronic slides. However, this format did not seem to work well for this particular unit. It is unclear whether it was the formality, the case study format, the vocabulary, or the novice presenter, but there was minimal discussion. The nurses who cared for the patient in the case study seemed defensive despite having provided excellent care. It became clear that Bioethics Bites needed to complement the unique pace, culture, and needs of this particular unit. After reflection, the rounds were shortened and simplified to micro-learning segments. Micro-learning sessions (i.e., learning new information or skills in small units) are effective to increase knowledge and confidence in the healthcare setting (De Gagne et al., 2019).

Implementing ethics rounds can demonstrate that ethics quality is a priority of facility leaders.

Regularly scheduled ethics rounds, versus a "when needed" status, increase ethics awareness, vocabulary, and real-time responses (Silén et al., 2016). Bioethics Bites sessions that were offered in person were 15 to 25 minutes and were integrated into the mid-day huddle. This mid-day huddle during the week is unique because it overlaps several shifts (i.e., 7a-3p, 7a -7p, 11a-7p, and 11a-11p) and includes personnel who would not be present on the weekend or overnight. The micro sessions rotated days of the week so as to increase accessibility for more nurses. The topic was selected from observed clinical situations that arose on the unit, questions from unit nurses, or by request of the nurse director and clinical nurse specialist. Bioethics Bites were informal guided discussions that included guest speakers who shared insight or resources to facilitate ethics quality, and case studies.

Six months into the process, some nurses voiced disappointment that they had not been scheduled to work on the day of the rounds. Thus, the micro session Bioethics Bites expanded again to include a brief recap in a newsletter (titled Bioethics Bytes) with bullet points and links to curated digital learning opportunities (e.g., podcasts, videos) to complement the in-person rounds. The newsletter was sent to the unit staff, maximizing access to ethics education for the nurses not physically present (i.e., not scheduled to work, scheduled for night shift, or working per diem). Combining the rounds and the newsletter reinforced the vocabulary, concepts, and cognitive autopsies that help establish ethics awareness and learning.

The nurses who cared for the patient in the case study seemed defensive despite having provided excellent care.

The Table illustrates planning information from Bioethics Bites/Bytes during the first year, the intended IE Model target level, and key takeaways or impressions that guided planning of subsequent Bites/Bytes.

Table. Summary of Unit Ethics Rounds Implementation

|

Delivery Mode |

Description of Bioethics Bites/Bytes |

Level 1: Targeted Decisions and Actions |

Level 2: Targeted Process and Systems |

Level 3: Targeted Environment and Culture |

Key Takeaways for Future Planning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

#1: In-person-formal longer session |

Case study of a known patient: Introducing principle ethics |

Session focused on fundamental vocabulary: |

Session answered: What information might you include in a case study and why? |

Session provided practice doing cognitive autopsy (e.g., What worked well? What can we do better?) |

"Crickets" –meant to be interactive but became didactic. Need to do micro-learning in this setting |

|

#2: In-person- |

Bedside advanced care planning/ Serious Illness Conversation (SIC) and how to document this in EMR |

Session focused on fundamental vocabulary: |

Session provided systems training: |

Session provided practice for Serious Illness Conversation using REMAP (e.g., Reframe-patients understanding of diagnosis, Expect emotion, Map patient goals, Align treatment with patient goals, and Propose a plan; Childers et al., 2017) |

Responded positively to learning a new skill of how to document SIC and use REMAP as a guide for conversation |

|

#3: In-person (ML) and newsletter, Bioethics Bytes |

Speaker: Ethics Consultation Service (e.g., what is it and how to access it) |

Session provided ethics committee information (e.g., who is on the ethics committee and what they do) |

Session provided process training: |

Session introduced hospital ethics leadership |

Very engaged, asking thoughtful questions’ created a newsletter to share this information with more nurses |

|

#4: In-person (ML) and newsletter |

Case study: What is decision-making capacity? |

Session focused on fundamental vocabulary: |

Session provided process training: |

Session introduced how to think about decision-making capacity, competence, and appropriate time for guardianship |

Staff still not comfortable with case study format, difficult to present case in a micro-learning session |

|

#5: Newsletter |

Role of hope in serious illness conversations |

Session (i.e., newsletter) focused on difficult conversations |

Newsletter provided process training: |

Newsletter included a link to a video that provided staff an opportunity to see a real-time difficult conversation |

Received an email and text that nurses enjoyed the newsletter, suggestion that residents would also benefit |

|

#6: In-person (ML) |

Speaker: Patient and Family Education and Resource Center: |

Session focused on fundamental vocabulary: |

Newsletter provided process training: |

Session introduced Patient and Family Education and Resource Center Leadership |

Interactive and nurses engaged |

|

#7: In-person (ML) and newsletter |

Nurse voice: Method of sharing the nursing perspective |

Session provided process training: Writing a nursing narrative (a 55-word essay) |

Session addressed the importance of the role of nursing and their narrative |

Received one 55-word essay within hours of rounds; continue to receive essays - "process is therapeutic" |

|

|

#8: In-person (ML) and Newsletter |

Medical futility: |

Vocabulary: |

Process teaching: |

How to integrate ethics teaching to practice |

Engaged and asking questions |

Results

The results of Bioethics Bites/Bytes have been twofold. The Integrated Ethics Model provided a framework for guiding the sessions. Most sessions incorporated all three foci as target. Only one did not include decisions. After a year of sessions, author JDM has observed that the unit staff has learned ethics vocabulary, the value of the case studies, the process of documenting serious illness conversations, and how to access resources that are available to them and their patients. The unit has engaged in building an environment that values ethics.

The Bioethics Bites/Bytes complement the unit culture and pace. The combination of the two maximizes the number of nurses exposed to continuing ethics education. This has normalized the ethics learning in the practice environment. Nurses have engaged by reaching out to the Ethics Consultation Service with questions and concerns whereas they had not regularly done so before inception of the unit-based ethics rounds. Unit nurses have made inquiries to the Patient and Family Education and Resource Center, have worked through challenging experiences using ethics lenses, and have requested possible topics and case studies. Finally, when the newsletter Bioethics Bytes was previewed by two experienced nurses, one suggested to share it with the attending and resident physicians associated with the unit.

Discussion

Unlike traditional ethics educational models, the Integrated Ethics Model targets three areas for quality ethics growth (Fox et al., 2010; Moon et al., 2019). All three foci, decisions, systems, and leadership have been highlighted within the first year of implementing Bioethics Bites on this unit. Unit-based ethics rounds help support quality ethics learning when they target all three foci (Fox et al., 2010; Moon et al., 2019). Each Bite was created from clinical situations or common ethical themes experienced on the unit with the intention of targeting more than one focus area. For example, one of the Bites shared guidance about the significance and process of documenting serious illness conversations in the medical record. By documenting serious illness conversations, the healthcare team, and the ethics committee, when needed, can recommend treatments that align more with the patient's values and, perhaps, prevent future conflicts. This Bite is an example of targeting all three focus areas, decisions and actions and environment and culture related to the ethics committee and its leadership, as well as a systems and process related to preventing conflict. Refer to the Table for detailed examples of the unit-based rounds.

Bioethics Bites/Bytes have taken ethics education from the classroom into practice.

Bioethics Bites/Bytes have taken ethics education from the classroom into practice. They provide nurses with experiential learning opportunities by using real-time case discussions to teach ethical principles, vocabulary, and how to apply ethics frameworks to various cases. They can also build upon previously shared information. For example, one of the ethics rounds content described the inaccurate use of the term medical futility. Nurses were able to identify a correct term, potentially inappropriate care, and apply several different ethical lenses to hypothetical and real-life case studies and determine how they could use the knowledge in their practice. The rounds also foster collaboration and build relationships.

The Bioethics Bites have provided a forum to address knowledge gaps related to ethics and build an ethical organizational culture and community. Implementing and organizing the ethics rounds is a systems-level approach to ethics (Schmitz et al., 2018), but also targets the organizational culture. In addition to presenting how to have conversations about serious illness and document this in the medical record, nurses learned how to access organizational resources such as the ethics consultation service and the Patient and Family Education and Resource Center. Participants also had the opportunity to discuss relevant concepts and definitions (e.g., the difference between capacity, competence, and guardianship).

Implementing and organizing the ethics rounds is a systems-level approach to ethics, but also targets the organizational culture.

Bioethics Bites/Bytes have created a way to empower and reinvigorate the unit ethics culture. For example, one unit-based educational activity emphasized elevating the nursing voice and experience. It was paired with a suggested activity and "how-to instructions" that included writing a 55-word narrative (Fogarty, 2010). These brief essays gave the nurses a process to capture their impactful moments, insights, and perspective. Some of the essays captured insights into sitting with a dying patient, the role of nursing in healthcare, and the uncertainty of the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. Some nurses reported the creating of essays as therapeutic and continue to write; a few have written more than one.

Conclusion

Traditional unit-based ethics rounds often center on identifying and preventing conflicts that arise from the care of a seriously ill patient (Schmitz et al., 2018). Bioethics Bites, unlike other unit-based ethics rounds, were developed using the Integrated Ethics Model to provide a framework for organizing rounds that focused on all three target areas. The learning has thus been multifaceted. Nurses who participated have new knowledge and insight into their critical role in quality and ethical care. They know when and how to access the ethics committee, which is focused on decisions and actions with a top-down design. The rounds have empowered staff with ethics language and strategies to process ethical conflict, a bottom-up design.

Nurses who participated have new knowledge and insight into their critical role in quality and ethical care.

The future direction of the Bioethics Bites/Bytes should include multidisciplinary members of the team. Research could explore the efficacy of using this model of unit-based ethics rounds to mitigate moral distress of staff and improve staff confidence and comfort with handling ethical dilemmas.

In implementation, it is imperative to consider the unit pace and culture. Integrating Bioethics Bites into regular huddles normalized this type of ethics education. Because the Bites are 15-20 minutes, researching topics and planning is easier, as is scheduling speakers who may have limited time. Additionally, the brevity keeps the topic simple and targeted; this facilitates the ease of attendance for nurses working on a busy unit. Larger topics are divided into smaller units that build upon each other. In sum, ethics rounds have been a feasible, sustainable, and beneficial process to include ethics education into practice.

Acknowledgements: The authors are thankful to Ellen Robinson, PhD, RN and Christine Marmen MEd, MSN, RN, OCN for their review and insight.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no competing interests to declare. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not reflect the position or policy of the University of Massachusetts Boston, Boston College, or Massachusetts General Hospital.

Authors

Jennifer D. Morgan, PhD, BSN, BA, RN-BC

Email: jennifer.morgan002@umb.edu

ORCID ID: 0000-0001-7272-5367

Jennifer Morgan received her doctorate degree in health policy in nursing with a focus on family engagement and serious illness. She is a board-certified clinical nurse who is a member of Massachusetts General Hospital Ethics in Clinical Practice Shared Governance Committee. She was also a graduate assistant for a course that addresses legal, ethical, and policy concerns in nursing at the Manning College of Nursing and Health Sciences at University of Massachusetts in Boston. Jennifer is the corresponding author for this article and can be reached at the above email.

Joanne Roman Jones, JD, PhD, RN

Email: joanne.romanjones@umb.edu

ORCID ID: 0000-0002-9639-9284

Joanne Roman Jones is an Assistant Professor at the University of Massachusetts Boston, Manning College of Nursing and Health Sciences. Dr. Roman Jones’ areas of expertise include decision making, patient safety, and quality of care. She currently teaches a course in Legal, Ethical, and Health Policy Issues in Nursing at UMass Boston.

Aimee Milliken, PhD, RN, HEC-C

Email: aimee.milliken@bc.edu

ORCID ID: 0000-0001-9077-1404

Aimee Milliken is an associate professor of the practice at the Connell School of Nursing. She practiced as a critical care nurse for over a decade and spent five years as a clinical ethicist, including serving as the Executive Director of a high-volume ethics service at a large academic medical center in Boston, Massachusetts, USA. She received a PhD from Boston College, where her dissertation involved the development and psychometric validation of the Ethical Awareness Scale. While enrolled in a postdoctoral fellowship, she received funding to research trends in ethics consultation. Dr. Milliken has taught, published, and presented nationally and internationally on the topics of nursing ethics and clinical ethics. She is the Co-Editor of the Clinical Ethics Handbook for Nurses: Emphasizing Context, Communication, and Collaboration (Springer, 2022).

References

Aulisio, M. P. (2016). Why Did Hospital Ethics Committees Emerge in the US? AMA Journal of Ethics, 18(5), 546–553. https://doi.org/10.1001/journalofethics.2016.18.5.mhst1-1605

Barkhordari-Sharifabad, M., Ashktorab, T., & Atashzadeh-Shoorideh, F. (2018). Ethical leadership outcomes in nursing: A qualitative study. Nursing Ethics, 25(8), 1051–1063. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733016687157

Childers, J. W., Back, A. L., Tulsky, J. A., & Arnold, R. M. (2017). REMAP: A Framework for Goals of Care Conversations. Journal of Oncology Practice, 13(10), e844–e850. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.2016.018796

Danis, M., Fox, E., Tarzian, A., & Duke, C. C. (2021). Health care ethics programs in U.S. Hospitals: Results from a National Survey. BMC Medical Ethics, 22(1), 107. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-021-00673-9

De Gagne, J. C., Park, H. K., Hall, K., Woodward, A., Yamane, S., & Kim, S. S. (2019). Microlearning in Health Professions Education: Scoping Review. JMIR Medical Education, 5(2), e13997. https://doi.org/10.2196/13997

Dimino, K., Louie, K., Banks, J., & Mahon, E. (2020). Exploring the Impact of a Dedicated Education Unit on New Graduate Nurses’ Transition to Practice. Journal for Nurses in Professional Development, 36(3), 121–128. https://doi.org/10.1097/NND.0000000000000622

Firn, J., Rui, C., Vercler, C., De Vries, R., & Shuman, A. (2020). Identification of core ethical topics for interprofessional education in the intensive care unit: A thematic analysis. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 34(4), 453–460. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2019.1632814

Fogarty, C. T. (2010). Fifty-five Word Stories: “Small Jewels” for Personal Reflection and Teaching. Family Medicine.

Fox, E., Bottrell, M. M., Berkowitz, K. A., Chanko, B. L., Foglia, M. B., & Pearlman, R. A. (2010). Integrated ethics: An Innovative Program to Improve Ethics Quality in Health Care. Innovation Journal, 15(2), 1–36. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,shib&db=bth&AN=60763000&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5071694

Fox, E., Danis, M., Tarzian, A. J., & Duke, C. C. (2022). Ethics Consultation in U.S. Hospitals: A National Follow-Up Study. American Journal of Bioethics, 22(4), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2021.1893547

Gebreheat G, Teame H. Ethical Challenges of Nurses in COVID-19 Pandemic: Integrative Review. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2021 May 6;14:1029-1035. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S308758. PMID: 33986597; PMCID: PMC8110276.

Hamric, A. B., & Wocial, L. D. (2016). Institutional Ethics Resources: Creating Moral Spaces. The Hastings Center Report, 46(5), S22–S27. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44159167

Hughes, M. T., & Rushton, C. H. (2022). Ethics and Well-Being: The Health Professions and the COVID-19 Pandemic. Academic Medicine, 97(3S), S98. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000004524

Jameton, A. (1984). Nursing Practice: The Ethical Issues. Prentice Hall.

Karakachian, A., Hebb, A., Peters, J., Vogelstein, E., Schreiber, J., & Colbert, A. (2024). Moral distress and intention to leave during COVID. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, 54(2), 111-117. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000001390

Milliken, A., & Grace, P. (2017). Nurse ethical awareness: Understanding the nature of everyday practice. Nursing Ethics, 24(5), 517–524. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733015615172

Moon, M., COMMITTEE ON BIOETHICS, Macauley, R. C., Geis, G. M., Laventhal, N. T., Opel, D. J., Sexson, W. R., & Statter, M. B. (2019). Institutional Ethics Committees. Pediatrics, 143(5), e20190659. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-0659

Morley, G., Ives, J., Bradbury-Jones, C., & Irvine, F. (2019). What is ‘moral distress’? A narrative synthesis of the literature. Nursing Ethics, 26(3), 646–662. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733017724354

Morley, G., & Sankary, L. R. (2023). Re-examining the relationship between moral distress and moral agency in nursing. NURSING PHILOSOPHY. https://doi.org/10.1111/nup.12419

Mulready-Shick, J., & Flanagan, K. (2014). Building the Evidence for Dedicated Education Unit Sustainability and Partnership Success. Nursing Education Perspectives (National League for Nursing), 35(5), 287–294. https://doi.org/10.5480/14-1379

Pavlish, C. L., Brown-Saltzman, K., Robinson, E. M., Henriksen, J., Warda, U. S., Farra, C., Chen, B., & Jakel, P. (2021). An Ethics Early Action Protocol to Promote Teamwork and Ethics Efficacy. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing: DCCN, 40(4), 226–236. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCC.0000000000000482

Robinson, E. M., Lee, S. M., Zollfrank, A., Jurchak, M., Frost, D., & Grace, P. (2014). Enhancing Moral Agency: Clinical Ethics Residency for Nurses. Hastings Center Report, 44(5), 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/hast.353

Schmitz, D., Groß, D., Frierson, C., Schubert, G. A., Schulze-Steinen, H., & Kersten, A. (2018). Ethics rounds: Affecting ethics quality at all organisational levels. Journal of Medical Ethics, 44(12), 805–809. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2018-104831

Silén, M., Ramklint, M., Hansson, M. G., & Haglund, K. (2016). Ethics rounds: An appreciated form of ethics support. Nursing Ethics, 23(2), 203–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733014560930

The Joint Commission. (2024) . Retrieved from: https://www.jointcommission.org/

Wocial, L., Ackerman, V., Leland, B., Benneyworth, B., Patel, V., Tong, Y., & Nitu, M. (2017). Pediatric Ethics and Communication Excellence (PEACE) Rounds: Decreasing Moral Distress and Patient Length of Stay in the PICU. HEC Forum, 29(1), 75–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10730-016-9313-0

Wocial, L. D., Miller, G., Montz, K., LaPradd, M., & Slaven, J. E. (2023). Evaluation of Interventions to Address Moral Distress: A Multi-method Approach. HEC Forum. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10730-023-09508-z

Wocial, L., Hancock, M., Bledsoe, P. D., Chamness, A. R., & Helft, P. R. (2010). An evaluation of unit-based ethics conversations. JONA’S Healthcare Law, Ethics and Regulation, 12(2), 48–54; quiz 55–56. https://doi.org/10.1097/NHL.0b013e3181de18a2